1. Introduction

The modern economy is systemic, regulated by individual markets, which includes both private entities, as well as enterprises and public institutions that are supposed to ensure that the needs of a specific customer are met [

1]. The economy in this branch covers three basic sectors—agriculture, industrial, and service [

2], and all activities carried out in a specific region (regional economy), country (national economy), and throughout the world (global economy) [

3]. The management of these sectors is carried out in order to create a wide variety of values and services that respond to the needs of individual consumers [

4].

The paper presents a cognitive problem of the classification and explication type. The theoretical verification of the research hypothesis was carried out with the use of the method of scientific cognition, the basis of which was Polish and foreign compact literature and articles published in scientific journals. For the empirical part, the basis was the primary materials in the form of a questionnaire and individual and direct interviews.

The authors aimed to analyse the impact of catering services on the tourism industry. The diversity of aspects of the research subject, oscillating around the main objective, influenced the separation of the intermediate objective, which became the diagnosis of the local catering industry.

The research hypotheses verified in this paper are:

H1. Gastronomic services influence the management of the tourism industry.

H2. The tourist is the main determinant shaping the demand.

H3. The tourist contributes to the achievement of benefits in the sphere of supply.

Tourists are consumers of many tourist services and are therefore carriers of demand for tourist benefits. The amount of income depends largely on the dynamic tourist traffic and the economic supply of tourist goods. The needs of the tourist are the driving force for the development of supply aimed at satisfying them. However, the size of the demand is also derived from the size and structure of the supply because without its existence the demand cannot be fulfilled. Tourist demand is an interdependent determinant of the formation of tourist supply.

Verification of the research hypotheses, from a theoretical point of view, was carried out using the method of scientific cognition, which was based on current Polish and foreign literature. The empirical part was based on primary materials in the form of a questionnaire and an individual and direct interview as well as found data. In view of the above, an attempt was made to analyse the functions of catering services in the Old Town in Gdańsk, which are mainly focused on serving tourists, and to analyse the supply of catering services in this area.

The paper consists of the following sections: Introduction, Literature Review, Materials and Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusions.

2. Literature Review

Due to the problems discussed in this article, special attention is paid to one of the few industries that is present on all markets in the world [

5], i.e., the tourism industry, which is also one of the most important industries in the international economy [

6]. The tourism industry includes all actors, companies, organizations [

7], and institutions that are not only linked by close cooperation [

8] but also involved in the production of tourism values and services [

9]. To put it simply, the tourism industry is a diverse, unique collection that is made up of all operating tourist institutions on the market [

10]. From this perspective, a large number of international organizations operate in the tourism industry [

11]. The tourism industry determines the appropriate infrastructure and services to handle the tourism movement and meet the needs of tourists from arrival to departure [

12].

Nutrition is one of the basic physiological needs in human life [

13], yet it is of secondary importance in tourism, because tourist, recreational, architectural, cultural, and other values are of primary importance in this field [

4]. There are, admittedly, such types of tourism as agritourism, rural tourism, gourmet tourism, enotourism [

14], or tourism related to regional cuisines, in which the types of cuisine offered and the quality of consumed food are an essential element [

15]. A specific form of tourism sometimes requires a different type of nutrition, which may not always be optimal in terms of health [

16]. Tourism often entails increased energy expenditure, as it is a physical activity of different intensities [

17], ranging from maximum; to equal to or even higher than that occurring in competitive sports; to mild, occurring in the everyday life of the average person, depending on its type [

18]. An important issue in tourism is therefore nutrition, which can be specific or diverse in health, maritime, or religious pilgrimage tourism [

19]. This is due to the specific nature of the forms of activity involved in tourism. The method and quality of nutrition, apart from tourist attractions, has a significant impact on the types and forms of undertaken tourist activities [

16,

20]. Therefore, due to the growing intensity of tourist traffic and the involvement of a significant part of the community in various types of tourism, it was decided in the present study to attempt to analyse the role of gastronomy in the tourism market. Food services are one of the oldest [

21] and most dynamically developing services on the catering market [

22]. Despite the dynamic development of the catering service industry, the literature on the subject does not have a clear definition of the concept nor a categorical approach to the function, scope, or classification of catering services [

23]. The multitude of terminology proves the diversity of the authors’ views, the complexity and interdisciplinarity of this concept, and the dynamic development of the industry observed in recent years as well as the change in its meaning in satisfying the various needs of the consumer.

The starting point for the preparation of this work is a reflection on the current state of catering establishments in Poland in the case of the Old Town in Gdańsk. This interest stems from the fact that modern tourism is strongly connected with culinary services and is the driving force behind this industry. Similar themes are identified in different contexts in scientific works. If local gastronomy is mentioned in scientific articles, it is in the context of outbound tourists’ needs for and attitudes toward food and food services and is used to assess the relationships between tourists’ attitudes toward food and food services and travel-related behavioural intentions, thus including the importance of local food and the quality of food and food service [

17]. Scientific research also shows that both economic and environmental development is increasingly linked to local food, which plays an irreplaceable role in preserving traditional culture, attracting tourists, and supporting the regional economy [

18]. A review of the literature on the subject revealed a gap in the area currently under study, which strengthened the rationale for taking up this topic. The authors address the issue of globalisation as a threat to local gastronomic identities [

24], focusing also on food product supply chains [

25]. The topic of food services in the context of tourism is discussed in terms of rural tourism [

26], agrotourism [

27], or ecotourism [

28]. Polish researchers focus their work on the quality of catering services [

29], demand for catering services, or culinary tourism in general [

30]. There are few studies that report on the impact of the local catering industry on the tourism industry.

3. Methodology

Providing food services occupies one of the most important areas of public life; therefore, it is worth looking at this phenomenon both from the perspective of the structure of the tourism market and the process of serving ready meals to tourists [

30]. The Central Statistical Office (GUS) recognises the permanent or seasonal activity of preparing and selling meals and drinks for consumption on the spot and takeaway as an establishment or catering point (GUS). The CSO divides catering establishments into generally available and focused on serving specific consumer groups (GUS). The Central Statistical Office also identifies forms of trade in the following catering establishments [

31]:

A bar, which has been defined as a self-service catering facility operating similar to a restaurant, with a limited range of services. This group also includes such forms of activity as a bistro, a diner, a cafe, a teahouse, or a beer house;

A restaurant is a catering establishment available to the general public, with full waiter service, offering a wide and varied range of dishes and drinks, served to consumers according to the menu. A restaurant should satisfy both the basic and exclusive needs of the consumer while providing relaxation and entertainment.

A seasonal catering facility is a catering point that is launched at a specific time, for a fixed period, and operates no longer than six months in a calendar year.

A canteen is a mass catering facility with a limited assortment, providing certain groups of consumers with meals (main courses) as well as breakfast and dinner. It can also issue one-off meals. It uses a subscription system. It is organisationally and locally separated, located on the premises of the workplace (employee canteen), schools, universities, and holiday centres.

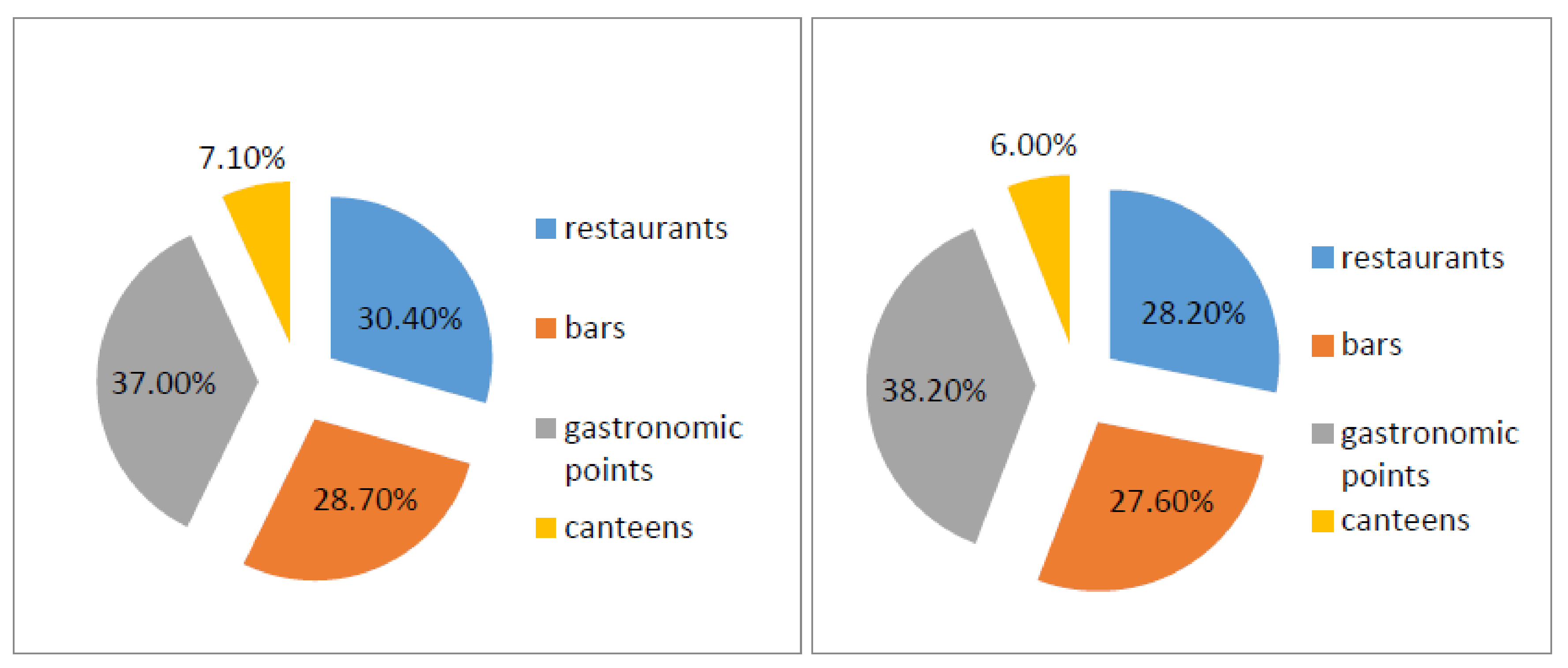

The number of catering establishments in Poland in 2018 was over 69,800. Out of that total, 38.2% were catering establishments, 28.2% restaurants, 27.6% bars, and 6.0% canteens. On the Polish market, it is noticeable that the number of catering establishments has decreased compared to 2017 (

Figure 1).

Statistical data from 2017 and 2018 show that the total number of catering establishments in Poland decreased by 0.4% (

Table 1). Compared to 2018, there were fewer restaurants, decreasing by 2.2 percent, fewer canteens, decreasing by 1.1 percent, and fewer bars, decreasing by 0.5%, while the number of eateries increased by 1.2% [

31].

In 2018, catering establishments employing more than 9 people began to disappear from the market. The number of such enterprises decreased by 7.5% compared to 2017 and accounted for 17,700 places, which is 25.3% of the total catering establishments in Poland. Regression was registered in all types of catering establishments: restaurants by 10.1%, bars by 5.8%, canteens by 3.8%, and outlets and catering by 7.5% [

31]. On the other hand, in 2019, the catering market recorded a slight increase in the number of catering establishments, recorded at 3% (approximately 6700 places). In 2019, there were mainly catering places serving fast-food [

32].

The above data shows the dynamics of changes in the gastronomic market and the adjustment of the nutritional offering to the constantly changing trends or customer expectations. As GfK states in its report “The catering market in Poland 2019”, Polish gastronomy is the fastest growing industry that must react quickly to economic changes and consumer moods in order to stay on the market [

33]. Despite the fluctuations in the number of catering establishments in recent years, the catering sector has been recording an increase in revenues from this activity for years (

Table 2).

The revenues from catering activities in the private in 2019 amounted to as much as 98.7%, and in the public sector, 1.3%.

Catering establishments may be run, inter alia, in hotels, motels, inns, hostels, camping sites, boarding houses, rest homes, and other short-term stay locations, as well as in train carriages and on passenger ships. Catering establishments do not include mobile retail outlets and vending machines. In turn, the condition of gastronomy in tourist facilities depends on their categories, which impose that in three- to five-star facilities, there should be at least one restaurant, an aperitif bar, or a coffee bar. Three-star facilities may not have a restaurant, provided that one is within a radius of 200 m. In two-star hotels and motels, an aperitif bar or a coffee bar is necessary, while in the first category of excursion houses, a restaurant is required and in category two, a canteen or a fast-food bar is required. Hostels should also have eateries.

The study surveyed 20 restaurateurs from the Old Town in Gdańsk and 438 random tourists over the age of 15. The aim of the study was to assess catering services provided in the Old Market Square in Gdańsk from the perspective of individual tourist service management. The survey method was chosen as the research method. It was reasonable to apply the indirect measurement method characterised by the fact that the survey questionnaire was handed directly to the respondent. The respondents answered the questions in writing. The method was chosen in order to survey a large group of tourists as quickly as possible.

The research tool consisted of two structured, short survey questionnaires used to verify the hypotheses. The questionnaires were created as a result of consultations with the appointed research team consisting of the authors of the study. The survey was conducted during the summer of 2018 (from 30.06 to 15.08). The questionnaire prepared for tourists contained only 5 questions in order not to be time-consuming and to convince as many tourists as possible to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaires were distributed to tourists in different restaurants in the Old Town of Gdańsk before they ordered a meal.

These surveys can be described as surveys of incidental, random communities because the respondents were not selected according to a purposeful scheme. No typologies or categories of tourists were taken into account in the study. The respondents had to declare that they were tourists and they were not asked about the organization, type, or purpose of the trip. The questionnaire addressed to owners of catering establishments was a representative survey, as the sample group was a statistical representation of the entire community of restaurateurs of the Old Town of Gdańsk. The questionnaire addressed to entrepreneurs contained a table in which 6 determinants of catering market competition were listed. Entrepreneurs rated their importance on a scale from 1 to 5. The questionnaire was supplemented by a direct interview with representatives of establishments. The survey was conducted from 10 to 15 July 2018.

The conducted survey was a survey of consumers’ opinions and a survey of entrepreneurs’ opinions. According to the openness of the respondent’s data, the survey conducted was anonymous. Simple, one-dimensional scales were used to represent the measured values of catering services, which reflected the values given by respondents to the assessed characteristics. A forced-ranking scale was used, where the respondent indicated the answer to a strictly specified category on the scale, which was a comparative scale.

The research was also based on secondary materials, i.e., data from the Central Statistical Office, research and analysis of the Polish Tourist Organization and reports “Poland on a plate” issued by Makro Cash & Carry, Poland in 2019, and the GfK report “catering market in Poland in 2019” regarding the situation of catering services in Poland in the tourism industry [

34,

35]. The statistical analysis used to help achieve the adopted research goal of this article consists in identifying key issues in catering services from the perspective of modern tourist services. The analysis is the basis for assessing the gastronomic offerings, their specificity, price of services, and the popularity of these services in the surveyed area. The research results can be used by small- and medium-sized catering enterprises, as well as in teaching material at universities.

4. Results

The area analysed in detail in this study, i.e., the Old Town in Gdańsk, in addition to various tourist attractions related to both the rich history of this city and its geographical location, is in fact a gastronomic showcase not only of Tri-City. This place is also famous. In 2018 alone, 3.1 million visitors came to the cosmopolitan city of Gdańsk for tourist purposes, which is 17% more than in 2017. A large group of visitors were tourists from abroad and the largest group were German tourists [

36]. In 2019, in the holiday season alone, 1,098,431 tourists came to Gdańsk, including approximately 680,000 domestic tourists and approximately 418,000 tourists from abroad (

Figure 2).

Every third tourist in Gdańsk is a tourist from abroad. The largest group of foreign tourists in 2019 were those traveling from Great Britain, which changed compared to previous years, when German tourists predominated Gdańsk (

Figure 3).

On average, tourists spend 4 nights in Gdańsk and about 43% of travellers arrive with their families [

37]. Gdańsk offers a variety of accommodation facilities, from luxury hotels to guesthouses, motels, hostels, and camps. A wide range of accommodation meets the expectations of every group of tourists. In 2018, 3,047,790 tourists were using the accommodation facilities in Gdańsk, including 572,393 from abroad, and 1,630,678 people stayed in hotels alone. The diversified accommodation base also adapted the food offering to the requirements of its customers (

Table 3).

In Gdańsk alone, there are over 1300 (data for 2018) seasonal and permanent catering establishments serving dishes from all corners of the world. The gastronomic situation in Gdańsk fully reflects the trends of the entire Polish gastronomic services market (

Table 4).

Gdańsk recorded a decrease in the number of catering establishments in 2018; however, revenues from the activity of this sector increased in this period (

Table 5).

Sales from the activity of catering services, despite the decrease in the number of catering establishments on the Gdańsk market, increased by 7284 Euro in 2018 compared to 2017. The highest income was obtained from the sale of culinary products.

The Old Town in Gdańsk is located in the Śródmieście district, and most of the eateries accumulate here. A decade ago, Gdańsk was an attractive tourist destination but it was not a culinary destination. There were few places where a tourist could eat well and culinary journeys were not in “fashion”. The contemporary gastronomic face of Gdańsk is in line with the current trends [

16], according to which nutrition has become the equivalent or even a forerunner in the cognitive values of tourism [

39]. They consist of a wide range of dishes from all over the world. Many restaurateurs are turning to culinary-skilled tourism, resigning from services for mass tourists. Despite the fact that many Gdańsk entrepreneurs in the catering industry are transforming to fit the requirements of culinary tourism, which is one of the fastest growing forms of tourism that offers travellers new forms and flavours of cuisine associated with the tradition of a given region, many stay with the fast-food offering, which is popular among the younger groups of tourists and tourists focused on visiting monuments who do not have time to enjoy a meal [

40]. However, these meals are unfavourable health-wise [

18], in which the share of unprocessed plant food is negligible [

41].

Choosing the right place for tourists is often not a simple task, therefore the city of Gdańsk, under the aegis of the City Hall, supports the dynamically developing gastronomic market, also wanting to help tourists choose the right restaurant. The “Tastes of Gdańsk” initiative popularises the gastronomic tradition of the city by offering tourists a restaurant guide, where you can find addresses of gastronomic establishments and learn about their gastro-specificity.

The study examined 20 restaurateurs from the Old Town in Gdańsk and 438 random tourists over 15 years of age. The aim of the study was to evaluate the catering services provided in the Old Market Square in Gdańsk from the perspective of individual tourist service management. Among the most common reasons for using a specific gastronomic offering, the respondents mentioned the taste of meals as the greatest incentive. (

Figure 4).

Another point influencing the choice of food offering was the price being appropriate to the product being served. As many as 28% of respondents choose a given culinary establishment because it is cheaper than the competition. Less important reasons for using the gastronomic point were the service, location of the premises, or cleanliness of the place of consumption. Tourists argued that they do not use these premises often enough (maybe they use them only once or several times a year); therefore, customer service, location of the gastronomic point, or cleanliness of the premises and hygienic conditions had less importance in their choices. When analysing the preferences of tourists in terms of dining establishments, it was found that individual tourists more frequently use the offering of fast-food, confectionery, and ice cream parlours, and less frequently choose restaurants as their place of consumption (

Figure 5).

The report “Poland on a plate” published in 2019 by Makro Cash & Carry determined that the average price of a dish in a restaurant should be between 5.50 Euro and 7.80 Euro, and encouraged the average Pole to eat a meal outside the place of residence. The report was developed as a result of research conducted throughout the country after 2018, which included all recipients of the above-mentioned company [

34].

The reference to the entire territory of the Republic of Poland is not an adequate indication of the functional specificity of individual Polish regions. In Gdańsk, the prices are much higher than the national average in the seasonal period, when it is less of a problem to meet a foreigner at a catering point than a compatriot. It is tourists in this historical area that fuel the income of entrepreneurs [

42], which they immodestly admitted to. Restaurant owners and managers were reluctant to admit actual sales, but a face-to-face interview with the staff shows that the average “voucher”, as they are called in the gastronomic slang of orders, is almost twice the average domestic price (

Figure 6).

The average price of a meal per person in the Old Market Square in Gdańsk ranges from 665 Euro to 1665 Euro and is much higher than the national average. Among the dishes consumed in gastronomic establishments, tourists most often indicated hot dishes and snacks, cold and hot drinks, and light alcohols. In terms of the menu, they ordered meat more often than fish.

Taking into account the form of the gastronomic establishment, the surveyed tourists most often chose pizzerias, premises serving traditional Polish dishes and chain fast-food, and food from food trucks, while sandwich shops were the least popular (

Figure 7). When asked if they were satisfied with the catering offerings in the Old Market Square in Gdańsk, most respondents answered yes (as many as 359, or 81.9% of the interviewed tourists).

The research on the supply side of catering services showed that, among Gdańsk catering companies, the highest rated (4.0) and most frequently used activities on a scale from 1 to 5, were: strengthening the brand, putting a lot of emphasis on customer service, and offering products of higher quality than the competition, as well as timeliness, flexibility, the ability to quickly react to changes in the market environment, etc. The surveyed entrepreneurs focus a lot of attention on the customer and on introducing the highest quality products in order to obtain consumer satisfaction. They focus on competent employees with unique qualifications and staff training, which allows them, if the market needs, to enrich their assortment offer with innovative dishes [

43]. Direct cooperation with suppliers and building lasting loyalty ties with them were also highly assessed by restaurateurs in the research. Most of the catering establishments in the Old Market Square in Gdańsk use the services of permanent, single suppliers. As confirmed by restaurateurs, timeliness and speed of deliveries, product quality, and attractive price directly translate to the quality level of the served meal and customer satisfaction (

Table 6).

By focusing attention on customer service at the premises and offering higher quality products (also due to suppliers), entrepreneurs claim that they are able to maintain and/or improve their competitive position in the market. Product quality is the most important aspect when both selecting suppliers and influencing competition on the catering services market. Marketing, promotion, and advertising expenditures are rated the lowest. In expanding the range, restaurateurs do not see a great advantage over the competition. They suggest that enriching the menu is related to the need to adapt to new or different consumer’s nutritional trends. It is worth paying attention to the intensive development of qualified tourism in recent years, which, in its form, sometimes coincides with competitive sports, and this type of tourist willingly eats a high-carbohydrate diet [

44].

5. Discussion

The gastronomic services market in Poland is developing dynamically and the Gdańsk market is a good example of this. Gdańsk is an important place for the development and location of gastronomy. This is due to the large number of potential consumers and, to a lesser extent, permanent residents and a high percentage of tourists. There is a wide variety of dining options, both traditional and trendy.

However, it should be remembered that, in 2020, the world was engulfed by a pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus, which changed the face of tourism and gastronomy [

45,

46]. This topic may become a contribution to the development of further studies analysing the state of Polish gastronomy during the pandemic after the containment of the virus. In addition, the catering services market in Gdańsk is growing dynamically and is subject to segmentation due to the diversity of consumer needs and the location of the outlets. It is difficult to characterise many segments, such as eateries, because there is no collected qualitative and quantitative statistical data.

The subject matter addressed in this paper is the result of a review of the literature that focuses on other aspects of both tourism and gastronomy. As previously mentioned, scholarly works present the topic addressed in a global perspective [

24], discuss the food supply chain [

25], or focus on the quality of gastronomy services and capture gastronomy in the context of culinary tourism as a trend in contemporary travel [

47]. Gastronomy is presented as a tourism product [

48] in tourism policy [

49] often in the context of sustainable development [

50]. Therefore, the authors attempted to show the impact of local catering services on tourism.

Empirical research conducted in the present study confirmed the hypotheses (

Table 7). With regard to the first hypothesis, catering services play an important role in the tourism market. They shape the quality of the tourist product offered by regions, its attractiveness and competitiveness [

51,

52]. Catering is an important factor stimulating tourism development [

53]. It influences both the volume of tourist traffic and the quality of its service. As confirmed by the data analysis, Gdańsk is one of the most attractive tourist destinations; an increase in tourist traffic was observed in 2019 compared to previous years. The food offerings of the Old Town of Gdańsk is an important source of income for the city. An increase in catering establishments was observed and tourists are satisfied with the forms of provision of such services.

The data obtained and the analysis of surveys conducted among tourists confirmed the second hypothesis. Conditions for the development of catering services are based on consumer preferences [

54]. Changes in the catering market are moving towards the development of establishments serving food that is inexpensive, prepared in a hurry, and served on the spot, or offering regional dishes.

Determinants of the development of the catering services market, as already mentioned above, are divided into demand and supply. Between these determinants, specific feedback can be observed. It is observed that the sphere of supply actively affects the sphere of demand and consumer preferences [

55]; in turn, consumers, through their changing needs, affect the proposals of the industry [

56]. Demand for catering services is constantly growing and the most important motive for tourists to use catering facilities is the quality of the dish and the price. Individual tourists rarely visit restaurants with waiter service and more often use fast-food services (as shown by the survey data aimed at tourists). Taking into account the results of surveys conducted in catering establishments in the Old Town of Gdańsk, tourists attach more importance to affordable prices and the taste of the food than to the cleanliness of the establishment or politeness of staff. In turn, restaurateurs emphasise that it is the customer who creates the market for catering services and it is his requirements that are the basis for serving as such, which confirms the third hypothesis

The presented work, apart from scientific values, also has a practical aspect that can be used in the successful management of catering services and in gaining an advantage in the competitive market of the culinary sector. The presented issues relating to the services of the catering industry cannot be considered exhaustive, however, because the discussed subject matter constitutes a multifaceted and interdisciplinary research area and requires further research on the part of science [

51] and new inventive activities of tourism organisers [

52,

57]. Nutrition in tourism will probably start to take into account the cultural, religious, or health-related nutritional values, which may contribute to a further increase in tourist traffic.

6. Conclusions

The catering market in Poland, especially in such areas as the Old Town in Gdańsk, is constantly developing, and in recent years there has been a great development of gastronomic offerings; therefore; the potential in this sector is significant. New points are constantly appearing on the gastronomic map of this historical part of Tri-City, where every tourist, regardless of the adopted form of tourism, can satisfy his or her needs without any problems. The gastronomic services market in Gdańsk is growing dynamically and is subject to segmentation due to the diversity of consumer needs and the location of the outlets. In Gdańsk gastronomy, in accommodation facilities, the development of restaurants and bars is visible. Strong competition motivates owners of, for example, restaurants and cafes to be creative, which manifests in a rich and varied menu. Ethnic catering establishments and chain establishments appear more and more often. European and Asian cuisines dominate among ethnic cuisines, which results from the culinary preferences of tourists.

Based on the results of the present study, it can be concluded that the demand for catering services is characterised by the most important motivation for individual tourists to use catering establishments: the quality of the dish and the price. An individual tourist rarely visits restaurants with waiter service and more commonly uses fast-food services. Tourists order hot snacks, as well as hot and cold drinks and alcohol in restaurants. Taking into account the assessment of the quality of the gastronomic offerings, tourists attach greater importance to the affordable prices and taste of the dishes; the cleanliness of the premises or the courtesy of service are less important. The analysis of the catering services supply segment in the Old Market Square in Gdańsk showed that restaurateurs pay the most attention to customer service in their premises and suppliers. Restaurateurs emphasise that it is the customer who creates the catering services market and that his requirements are the basis for serving as such. Consumer tourists are an increasingly demanding group of society, which strongly influences the development of the competitiveness of gastronomic enterprises, meeting both the most basic human needs, i.e., nutrition and safety, as well as those of a higher order, e.g., related to respect and tolerance. Another key element of the competitiveness of catering establishments is the selection and cooperation with the appropriate supplier of food and non-food raw materials, ensuring continuity of production necessary for the functioning of the premises and influencing the quality and taste of the dishes offered. The development of the catering services sector depends on consumer preferences. The increasing demand for catering services and changes in eating habits, expressed in the increase in popularity of the original forms of catering services as well as the change and development of the structure of the catering base, affect the management of the catering industry and raise the level of customer service.

The research hypotheses presented in the article, which determined the structure of the work, have been confirmed. Food services influence the management of the tourism industry and the tourist is the main determinant of demand and of contributing to the benefits of supply. Considering the importance of the demand created by the tourist segment for the development of the gastronomic services market, it is advisable to take into account the specific needs of these consumers when creating the marketing strategy of the establishments and to systematically monitor changes in their market behaviour.

Research has shown that it is important to diagnose consumer needs. If we do not know the preferences of tourists and do not satisfy these expectations, thus offering an incomplete tourist product, we will experience a regression in the tourist economy. Analysis of the research results demonstrates a practical implication, showing the importance of demand in tourist catering. However, it is necessary to take into account the values and specificity or variability of each tourist market and diagnose it in terms of tourist demand. The problems presented in the article cannot be considered exhaustive because the subject matter is a multifaceted and interdisciplinary research area. The research was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, it would be worthwhile to re-diagnose catering services on the local market in question. The research could be based on structural equation modelling (SEM-PLS) to obtain measures of causal variables on a quantitative scale [

53], which would ensure high reliability of the research results [

54]. After repeating the survey, we will use structural equation modelling (SEM-PLS) in future analyses, which will facilitate a search for hidden relationships among quantitative data and help to discover cause-and-effect relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; methodology, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; software, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; validation, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; formal analysis, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; investigation, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; resources, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; data curation, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; writing—review and editing, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; visualization, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; supervision, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; project administration, W.P., D.K. and I.M.; funding acquisition, W.P., D.K. and I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was financed within the framework of the program of the Minister of Science and Higher Education in Poland under the name “Regional Excellence Initiative” in the years 2019–2022, project number 001/RID/2018/19; the amount of financing was PLN 10,684,000.00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data used for analysis is available on request from second author.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Leon Dorozik and Edward Altman for scientific support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wilk, M. The tourism industry as a driving force for the economy of the European Union. In Challenges and Perspectives of Contemporary Organization. Economic and Public Context; Nowakowska-Grunt, J., Kabus, J., Eds.; Publishing House: Częstochowa, Poland, 2017; pp. 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtaszek, H.; Miciuła, I. Analysis of factors giving the opportunity for implementation of innovations on the example of manufacturing enterprises in the Silesian province. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuzminski, L.; Jalowiec, T.; Masloch, P.; Wojtaszek, H.; Miciula, I. Analysis of factors influencing the competitiveness of manufacturing companies. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2020, 23, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kabus, J. Marketing in Tourism. AD ALTA J. Interdiscip. Res. 2015, 5, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.L.J. How Big, How Many? Enterprise Size Distributions in Tourism and Other Industries. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagayama, H.; Shizuma, K.; Toguch, M.; Mizuhara, H.; Machida, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Ebine, N.; Higaki, Y.; Tanaka, H. Effect of the Health Tourism weight loss programme on body composition and health outcomes in healthy and excess-weight adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aho, S.K. Towards a general theory of touristic experiences: Modelling experience process in tourism. Tour. Rev. 2001, 56, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miciuła, I.; Rogowska, K.; Stępień, P. Swot Analysis for the Marketing Strategy of Tourist Destinations on the Example of the City of Międzyzdroje—Case Study. In Proceedings of the 35th IBIMA, Seville, Spain, 1–2 April 2020; pp. 16631–16640. [Google Scholar]

- Croes, R.; Ridderstaat, J.; Bąk, M.; Zientara, P. Tourism specialization, economic growth, human development and transition economies: The case of Poland. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G.; Dubelaar, C. A General Theory of Tourism Consumptions System. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabiddu, F.; Lui, T.-W.; Piccoli, G. Managing value co-creation in the tourism industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Villegas, A.; Delgado-Rodriguez, M.; Alonso, A.; Schlatter, J.; Lahortiga, F.; Majem, L.S.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A. Association of the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern with the Incidence of Depression. The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra, University of Navarra Follow-up (SUN) Cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Nunez-Cordoba, J.M.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Beunza, J.J.; Vazquez, Z.; Benito, S.; Tortosa, A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Adherence Mediterranean diet and risk of developing diabetes: Prospective cohort study. Br. Med. J. 2008, 336, 1348–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seddighi, H.R.; Theocharous, A.L. A model of tourism destination choice: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilis, W.; Czaja, S.; Pluta, R.; Pilis, T.; Zając, A. Hiking around Sokole Mountains; Żabińska, T., Ed.; The Department of Tourism, Upper Silesian School of Economics in Katowice: Katowice, Poland, 2007; pp. 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Event Tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.C.; Campbell, T.M. Modern principles of nutrition. In Groundbreaking Research on the Effects of Nutrition on Health; Galaxy: Łódź, Poland, 2011; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Poulianiti, K.P.; Havenith, G.; Flouris, A.D. Metabolic energy cost of workers in agriculture, construction, manufacturing, tourism, and transportation industries. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hawley, J.A.; Leckey, J.J. Carbohydrate Dependence During Prolonged, Intense Endurance Exercise. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miciuła, I. Methods of Creating Innovation Indices Versus Determinants of Their Values. In Eurasian Economic Perspectives; Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 87, pp. 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhana, N.; Islam, S. Exploring Consumer Behavior in the Context of Fast Food Industry in Dhaka City. World J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 1, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chalak, A.; Abou-Daher, C.; Abiad, M.G. Generation of food waste in the hospitality and food retail and wholesale sectors: Lessons from developed economies. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; De Coteau, D.A. Food waste management in hospitality operations: A critical review. Tour. Manag. 2018, 71, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.N.; Lumbers, M.; Eves, A. Globalisation and food consumption in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sellitto, M.A.; Hermann, F.F. Prioritization of green practices in GSCM: Case study with companies of the peach industry. Gest. Prod. 2016, 23, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, M. Small Firms and Wine and Food Tourism in New Zealand: Issues of Collaboration, Clusters and Lifestyles; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mura, L.; Kljucnikov, A. Small Businesses in Rural Tourism and Agrotourism: Study from Slovakia. Econ. Sociol. 2018, 11, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brochado, A.; Troilo, M.; Rodrigues, H.; Oliveira-Brochado, F. Dimensions of wine hotel experiences shared online. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 32, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziadkowiec, J.M. The Quality of Catering Services from the Point of View of a Motorized Tourist; Paragraph: Krakow, Ploand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Derek, M. (Ed.) Directions for the Development of Gastronomic Services in the Warsaw District of Śródmieście. Work and Geographical Studies; University of Warsaw, Faculty of Geography and Regional Studies: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- GUS. Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/metadane/metryka/2505 (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Macro Cash & Carry Report. Poland on a Plate. 2019. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/releases/2987 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- GfK Report. Catering Market in Poland. 2019. Available online: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/2405078/cms-pdfs/fileadmin/user_upload/dyna_content/pl/gfk_raportrynekgastronomiczny2019_oferta_29112019.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Andaleeb, S.; Conway, C. Customer satisfaction in the restaurant industry: An examination of the transaction-specific model. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. Terms Used in Official Statistics. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/metainformacje/slownik-pojec/pojecia-stosowane-w-statystyce-publicznej.html (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Gdańsk Tourist Organization (GTO). Available online: https://www.pot.gov.pl/pl/archiwum/gdanska-organizacja-turystyczna-oraz-gdanski-convention-bureau-czlonkiem-icca-2 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Statistical Office in Gdańsk (SOG). Statistical Yearbook of Pomorskie Voivodeship. 2019. Available online: https://gdansk.stat.gov.pl/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Eurostat. 2020. Available online: http://europa.eu/statistics/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Zwolak, J. The effectivenrss of innovation projects in Polish industry. Rev. Innov. Compet. J. Econ. Soc. Res. 2016, 2, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilis, A.; Pilis, K.; Pilis, W. Influence of the type of diet and physical activity on body weight and functioning of the organism, Scientific Papers of Akademia im. Jan Długosz in Częstochowa. Phys. Cult. 2012, 11, 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, S.; Luis, J.; Perez-Ruiz, S. Development of capabilities from the innovation of the perspective of poverty and disability. J. Innov. Knowl. 2017, 2, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabus, J.; Kana, R.; Miciuła, I.; Nowakowska-Grunt, J. Local Government Planning for Social Benefits with example of Hannover city. Eurasian J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeukendrup, A.E. Modulation of carbohydrate and fat utilisation by diet, exercise and environment. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003, 31, 1270–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bieszk-Stolorz, B.; Dmytrów, K. A survival analysis in the assessment of the influence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the probability and intensity of decline in the value of stock indices. Eurasian Econ. Rev. 2021, 11, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Alshazly, H.; Idris, S.A.; Bourouis, S. Evaluating the Impact of COVID-19 on Society, Environment, Economy, and Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberato, P.; Mendes, T.; Liberato, D. Culinary Tourism and Food Trends. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Smart Systems; Dalam, Á., Rocha, A., Abreu, J.V., de Carvalho, D., Liberato, E., González, A., Liberato, P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, A. Gastronomy as a tourist product. In Tourism and Hotel Industry; Higher School of Tourism and Hotel Industry in Łódź: Łódź, Poland, 2007; pp. 103–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jong, A.; Varley, P. Food tourism policy: Deconstructing boundaries of taste and class. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertella, G. Re-thinking sustainability and food in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szturo, M.; Włodarczyk, B.; Burchi, A.; Miciuła, I.; Szturo, K. Improving relations between a state and a business enterprise in the context of counteracting adverse effects of the resource curse. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Gómez, A.; Ruiz-Palomo, D.; Fernández-Gámez, M.A.; García-Revilla, M.R. Sustainable Tourism Development and Economic Growth: Bibliometric Review and Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellitto, M.A.; Hermann, F.F. Influence of Green Practices on Organizational Competitiveness: A Study of the Electrical and Electronics Industry. Eng. Manag. J. 2019, 31, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, A. Structural modeling in the analysis of consumer behavior: Comparison of methods based on analysis of covariance (CB-SEM) and Partial Least Squares (PLS-SEM). Intern. Trade 2018, 6, 247–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kabus, J.; Nowakowska-Grunt, J. Tourism Management as an Element of Contemporary International Relations. World Sci. News 2016, 48, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowska, E.; Levytska, G. Rynek Usług Gastronomicznych w Polsce na Początku XXI Wieku; Nr. 74; EIOGZ: Warsaw, Poland, 2009; pp. 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Yi-Chin, L.; Chin-Chin, C. Needs Assessment for Food and Food Services and Behavioral Intention of Chinese Group Tourists Who Visited Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Hu, B. Authenticity, Quality, and Loyalty: Local Food and Sustainable Tourism Experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).