How to Monitor and Evaluate Quality in Adaptive Heritage Reuse Projects from a Well-Being Perspective: A Proposal for a Dashboard Model of Indicators to Support Promoters

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aim and Structure of the Paper

- Regarding the discipline of economic evaluation, is there a set of indicators in the literature to evaluate, ex-post, the interventions of adaptive heritage reuse? Does this set of indicators include the issues of well-being and quality of life that are relevant today to illustrate the effectiveness of interventions in this field? Is it possible to extend the indicators used in public economic planning (in the specific Italian case, the BES index—Benessere Equo e Sostenibile/Equitable and Sustainable Well-being) also to projects developed with a view to public–private partnership?

- Regarding the discipline of architectural restoration, is this set of indicators effective for assessing the compatibility of the reuse intervention with the architectural heritage? Starting from the reflections in progress developed in the scientific debate on the non-conflictual relationship between architectural restoration and well-being, is it possible to update the literature downstream with the case study investigated?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Well-Being and Architectural Restoration

2.2. Well-Being and Economic Evaluation of Projects

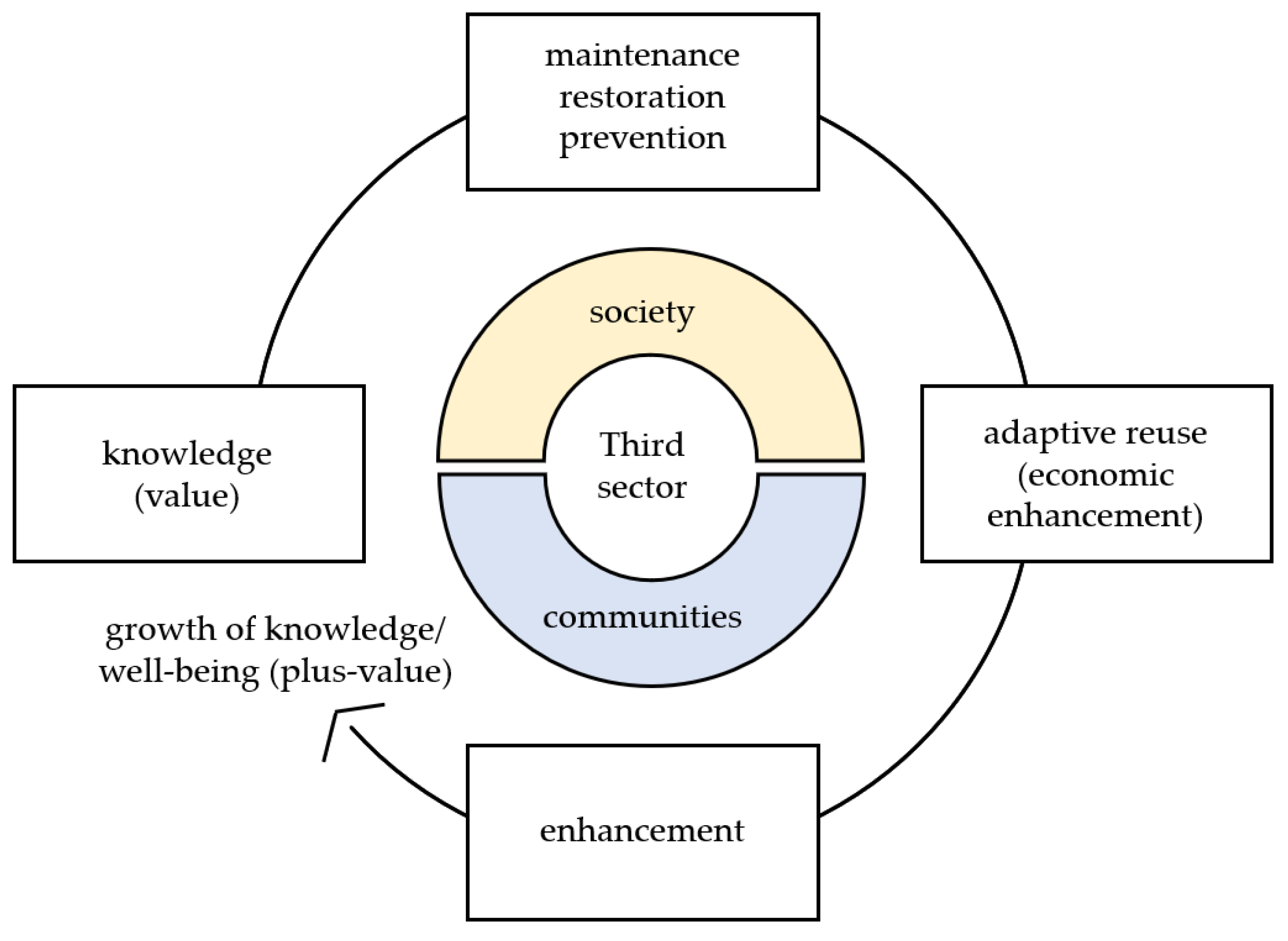

2.3. Third Sector and Architectural Heritage

3. Case Study: Funding Calls on Architectural Heritage and the Third Sector in Italy

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Phase 1: Census of Calls for Funding (2014–2020)

- Websites of entities and associations in support of Third Sector bodies. They are configured as dissemination portals that have the objective of training and informing nonprofit organisations, making the legislation accessible and facilitating its application, identifying opportunities for support: Associazione Nazionale dei Centri di servizio per il volontariato CSVnet [103], Forum Nazionale del Terzo settore [104], Cantiere Terzo Settore [105], Italia non-profit [106], and association LABSUS—Laboratorio per la sussidiarietà [107].

- Sites containing databases of calls for funding aimed at private companies, nonprofit organisations, public bodies (benefit company Excursus) [108].

4.2. Phase 2: Funding Calls on Adaptive Heritage Reuse

4.3. Phase 3: Dashboard Model of Indicators

5. Results

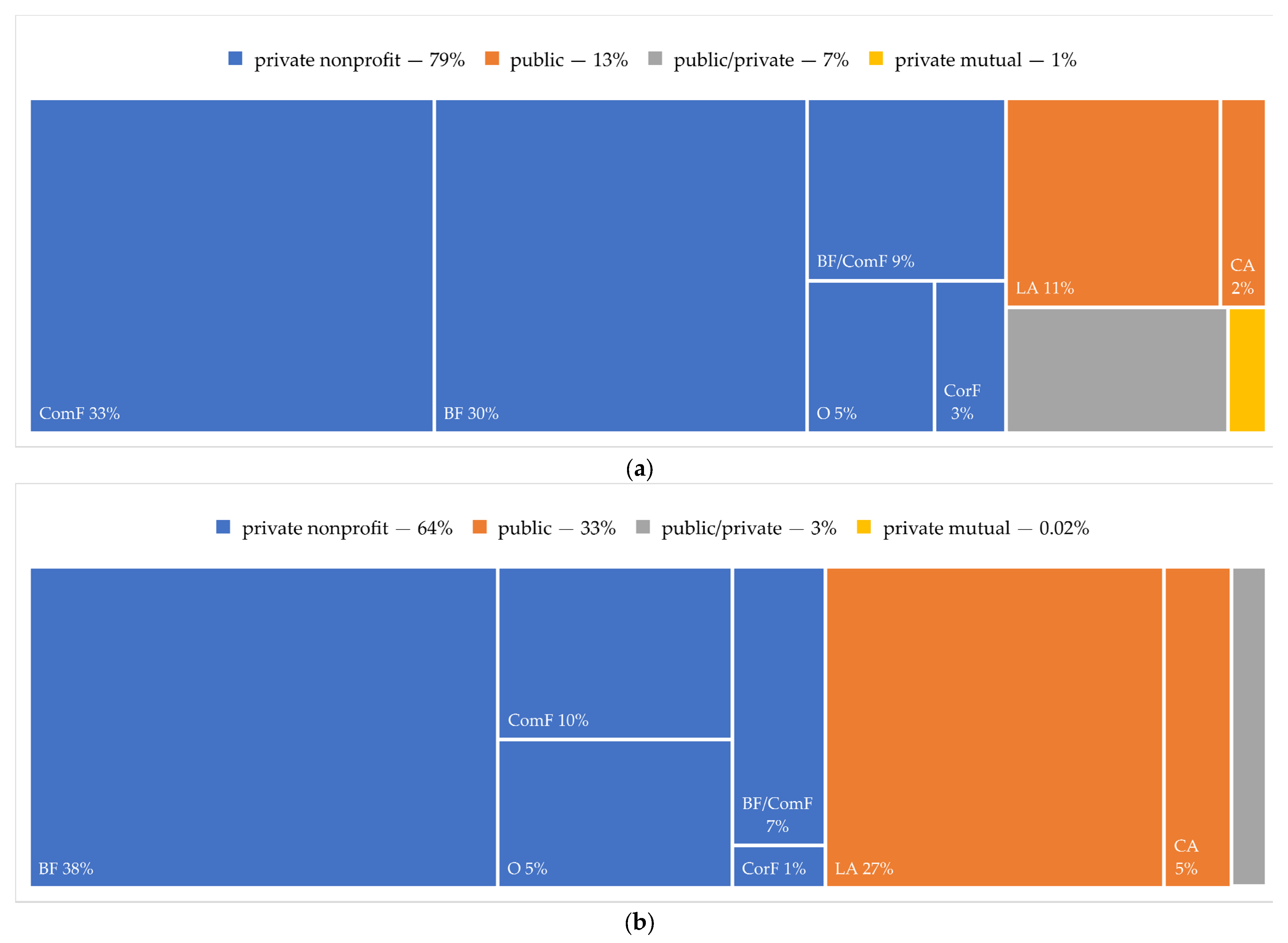

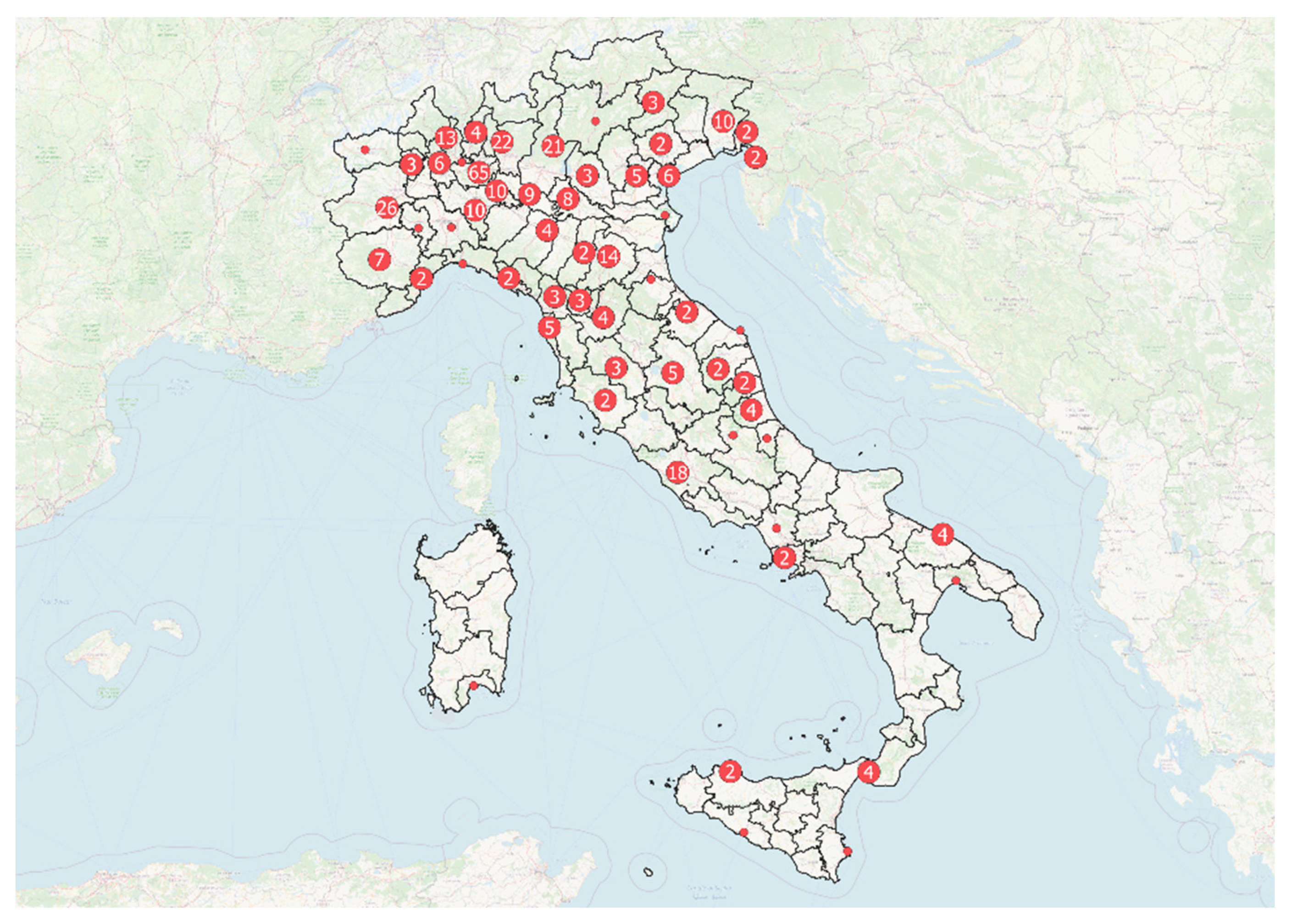

5.1. Results of Phase 1

5.2. Results of Phase 2

5.3. Results of Phase 3

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Council of Europe (CoE). Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. Faro Declaration of the Council of Europe’s Strategy for Developing Intercultural Dialogue. 2005. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Europa Nostra. COVID-19 & BEYOND: Challenges and Opportunities for Cultural Heritage. 2020. Available online: https://www.europanostra.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/20201014_COVID19_Consultation-Paper_EN.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Risk Management in the Area of Cultural Heritage 2020/C 186/01. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020XG0605(01) (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Roigé, X.; Arrieta-Urtizberea, I.; Seguí, J. The Sustainability of Intangible Heritage in the COVID-19 Era—Resilience, Reinvention, and Challenges in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Shock Cultura: COVID-19 e Settori Culturali e Creativi; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/shock-cultura-covid-19-e-settori-culturali-e-creativi-e9ef83e6/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- UNESCO. Intangible Cultural Heritage in Emergencies Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Addressing Questions of ICH and Resilience in Times of Crisis: Report; UNESCO Office Venice and Regional Bureau for Science and Culture in Europe: Venice, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374652 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Kono, T.; Adetunji, O.; Jurčys, P.; Niar, S.; Okahashi, J.; Rush, V. The Impact of COVID-19 on Heritage: An Overview of Responses by ICOMOS National Committees (2020) and Paths Forward. 2020. Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2415/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- De Filippi, F.; Coscia, C.; Cocina, G.G. Collaborative platforms for social innovation projects. The Miramap case in Turin (Piattaforme collaborative per progetti di innovazione sociale. Il caso Miramap a Torino). TECHNE 2017, 14, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregonara, E.; Giordano, R.; Ferrando, D.G.; Pattono, S. Economic-Environmental Indicators to Support Investment Decisions: A Focus on the Buildings’ End-of-Life Stage. Buildings 2017, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fregonara, E.; Giordano, R.; Rolando, D.; Tulliani, J.M. Integrating Environmental and Economic Sustainability in New Building Construction and Retrofits. J. Urban Technol. 2016, 23, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. COVID-19 and Well-Being. Life in the Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/wise/covid-19-and-well-being-1e1ecb53-en.htm (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Sofaer, J.; Davenport, B.; Sørensen, M.L.S.; Gallou, E.; Uzzell, D. Heritage sites, value and wellbeing: Learning from the COVID-19 pandemic in England. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 27, 1117–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage Alliance. Heritage, Health and Well-being: A Heritage Alliance Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.theheritagealliance.org.uk/our-work/publications/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Volpe, G. Un Faro per il patrimonio Culturale nel post-COVID-19. Scienze Del Territorio 2020, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.H.; Hou, J. Developing a framework to appraise the critical success factors of transfer development rights (TDRs) for built heritage conservation. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perperidou, D.-G.; Siori, S.; Doxobolis, V.; Lampropoulou, F.; Katsios, I. Transfer of Development Rights and Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Case Study at Athens Historic Triangle, Greece. Heritage 2021, 4, 4439–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abastante, F.; Lami, I.; Mecca, B. How Covid-19 influences the 2030 Agenda: Do the practices of achieving the Sustainable Development Goal 11 need rethinking and adjustment?/Come il COVID-19 influenza l’Agenda 2030: Le pratiche di raggiungimento dello SDG11 devono essere ripensate e aggiornate? Valori e Valutazioni 2020, 26, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscia, C.; Rubino, I. Unlocking the Social Impact of the Built Heritage Project: Evaluation as Catalyst of Value? In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Allegro, I.; Lupu, A. Models of Public Private Partnership and financial tools for the cultural heritage valorisation. Urbanistica Informazioni-INU 2018, 1–6. Available online: https://www.clicproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Models-of-Public-Private-Partnership-and-financial-tools-for-the-cultural-heritage-valorisation-Ivo-Allegro-Aliona-Lupu.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Consiglio, S.; D’Isanto, M.; Pagano, F. Partnership Pubblico Private e organizzazioni ibride di comunità per la gestione del patrimonio culturale/Public Private Partnerships and hybrid community organizations for the management of cultural heritage. Il Capitale Culturale 2020, 11, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Il Terzo Settore e gli Obiettivi di Sviluppo Sostenibile. Rapporto 2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.forumterzosettore.it/files/2017/12/Forum3settore_iPad.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Forum Terzo Settore. Il Terzo Settore e Gli Obiettivi di Sviluppo Sostenibile. Rapporto 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.forumterzosettore.it/2021/05/28/il-terzo-settore-e-gli-obiettivi-di-sviluppo-sostenibile-rapporto-2021/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- EURICSE. Un Action Plan per il Terzo Settore e L’Economia Sociale. 2020. Available online: https://www.euricse.eu/it/un-action-plan-per-il-terzo-settore-e-leconomia-sociale-lettera-aperta-al-presidente-conte/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Bassanini, F.; Treu, T.; Vittadini, G. Una Società di Persone? I Corpi Intermedi Nella Democrazia di Oggi e di Domani; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Giovando, G.; Mangialardo, A.; Sorano, E.; Sardi, A. Impact Assessment in Not-for-Profit Organizations: The Case of a Foundation for the Development of the Territory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvo, L.; Pastore, L.; Mastrodascio, M.; Tricarico, L. The Impact of COVID-19 on Public/Third-Sector Collaboration in the Italian Context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, S. Prosperità Inclusiva. Saggi di Economia Inclusiva; Studium: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, A.M. Welfare e no Profit in Europa. Profili Comparati; Giappichelli: Turin, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pavan-Woolfe, L.; Pinton, S. (Eds.) Il Valore del Patrimonio Culturale per la Società e le Comunità. La Convenzione del Consiglio d’Europa tra Teoria e Prassi; Alinea: Padua, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nocca, F.; Gravagnuolo, A. Matera 2019 capitale europea della cultura: Città della natura, città della cultura, città della rigenerazione. BDC. Bollettino Del Centro Calza Bini 2017, 17, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbene, D. Riuso del Patrimonio Architettonico, Sostenibilità e Benessere. Nuovi Scenari per il Restauro. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy. unpublished.

- Smith, B.J.; Tang, K.C.; Nutbeam, D. WHO Health Promotion Glossary: New terms. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 340–345. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/heapro/article/21/4/340/688495 (accessed on 21 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, M.A. Health, wellness and wellbeing. Revue Interventions Économiques 2019, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Council of Europe. Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe (ETS No. 121). Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=treaty-detail&treatynum=121 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Barbetta, G.P.; Cammelli, C.; Della Torre, S. (Eds.) Distretti Culturali Dalla Teoria alla Pratica; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pracchi, V.; Chiapparini, A. Il restauro e i possibili modi per “comunicare” il patrimonio culturale. Il Capitale Culturale 2013, 8, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nijkamp, P. (Eds.) Le Valutazioni per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile Della Città e del Territorio; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Manacorda, D. L’Italia agli Italiani. Istruzioni e Ostruzioni per il Patrimonio Culturale; Edipuglia: Bari, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pane, A. Per un’etica del restauro. In RICerca/REStauro; Fiorani, D., Scient. Coord. Sezione 1A Questioni Teoriche: Inquadramento Generale; Musso, S.F., Ed.; Quasar: Rome, Italy, 2017; pp. 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dezzi Bardeschi, M. Restauro: Teorie per un secolo. Ananke 1997, 19, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Napoleone, L. Bellezza per il nostro tempo. In Proceedings of the Conference EURAU’10, Naples, Italy, 23–26 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonara, G. Orientamenti teorici e di metodo nel restauro. In Restauro e Tecnologie in Architettura; Fiorani, D., Ed.; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dezzi Bardeschi, M. Restauro: Due Punti e da Capo; Gioeni, L., Ed.; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fancelli, P. Restauro ed etica. Palladio 1993, 11, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pane, G. Il restauro come etica. Butlletí de la Reial Acadèmia Catalana de Belles Arts de Sant Jordi 1996, 10, 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, A. Dal restauro alla conservazione: Dall’estetica all’etica. Ananke 1997, 19, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, A.; Torsello, B.P. Che Cos’è il Restauro? Nove Studiosi a Confronto; Marsilio: Venice, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, A. Conservazione e fruizione del patrimonio architettonico: Un problema etico. Territorio 2013, 64, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manacorda, D. Patrimonio culturale, un diritto collettivo. In Proceedings of the Conference on La Democrazia Della Conoscenza. Patrimoni Culturali, Sistemi Informativi e Open Data: Accesso Libero ai Beni Comuni? Trieste, Italy, 29 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Volpe, G. Un Patrimonio Italiano. Beni Culturali, Paesaggio e Cittadini; Utet: Turin, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Prescia, R.; Trapani, F. (Eds.) Rigenerazione Urbana, Innovazione Sociale e Cultura del Progetto; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Prescia, R. L’eredità di John Ruskin “critico della società”. Restauro Archeologico 2019, 2, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Napoleone, L. La tutela del patrimonio culturale negli ultimi decenni. Riflessioni e possibile cambiamento di paradigma. Quaderni dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Architettura 2019, 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, I. Cultural heritage rights: From ownership and descent to justice and well-being. Anthropol. Q. 2010, 83, 861–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Chan, E.H.W.; Li, L.H. Transfer of development rights as an institutional innovation to address issues of property rights. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, S.; Rajabi, M. The Restoration of St. James’s Church in Como and the Cathedral Museum as Agents for Sustainable Urban Planning Strategies. Land 2022, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippschild, R.; Zöllter, C. Urban Regeneration between Cultural Heritage Preservation and Revitalization: Experiences with a Decision Support Tool in Eastern Germany. Land 2021, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, C. Rigenerare per valorizzare. La rigenerazione urbana gentile e la riduzione delle disuguaglienze. Aedon 2021, 2. Available online: http://www.aedon.mulino.it/archivio/2021/2/vitale.htm (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Fusco Girard, L. Risorse Architettoniche e Culturali; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- De Filippi, F.; Coscia, C.; Guido, R. From smart-cities to smart-communities: How can we evaluate the impacts of innovation and inclusive processes in urban context? Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2019, 8, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Vecco, M. The “Intrinsic Value” of Cultural Heritage as Driver for Circular Human-Centered Adaptive Reuse. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nocca, F.; Gravagnuolo, A. Matera: City of nature, city of culture, city of regeneration. Towards a landscape-based and culture-based urban circular economy. Aestimum 2019, 74, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, R.; Zia, U. Multidimensional Wellbeing: An Index of Quality of Life in a Developing Economy. Soc. Indic Res. 2013, 114, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattia, S.; Oppio, A.; Pandolfi, A. La città per gli ultimi: Politiche per la felicità/The city for the last: Policies for happiness. In Human Rights and the City Crisis; Beguinot, C., Ed.; Giannini: Naples, Italy, 2012; pp. 370–395. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.-P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. 2010. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/8131721/8131772/Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi-Commission-report.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- OECD. How’s Life?: Measuring Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/how-s-life_9789264121164-en (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- OECD. How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/how-s-life/volume-/issue-_9870c393-en (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- OECD. OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/wise/oecd-guidelines-on-measuring-subjective-well-being-9789264191655-en.htm (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Scott, K. Measuring Well-Being; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciosa, A. La Valutazione dei Processi Urbani per la Promozione della Salute: Una Sperimentazione al Paesaggio Storico dell’area Metropolitana di Napoli. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Rapporto BES 2020. Il Benessere Equo e Sostenibile in Italia; ISTAT: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: http//www.istat.it/it/archivio/207259 (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Law 163/2016, Modifiche alla legge 31 dicembre 2009, n. 196, concernenti il contenuto della legge di bilancio. 4 August 2016.

- ESPON. HERIWELL—Cultural Heritage as a Source of Societal Well-Being in European Regions. Inception Report—Conceptual Framework; Espon EGTC: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://www.espon.eu/HERIWELL (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Musco, D. Gestione e Valorizzazione del Patrimonio Culturale Immobile: Gli Accordi enti Pubblici–Enti Non Profit. Master’s Thesis, Università di Pisa, Pisa, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Composta, E. Concessione di Beni Pubblici degli Enti Locali a Organizzazioni del Terzo Settore/Public Assets Concession Contracts between Local Authorities and Third Sector Organisations). Euricse Work. Pap. 2018, 101, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consiglio, S.; Riitano, A. (Eds.) Sud Innovation. Patrimonio Culturale, Innovazione Sociale e Nuova Cittadinanza; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cottino, P.; Zandonai, F. Progetti d’impresa sociale come strategie di rigenerazione urbana: Spazi e metodi per l’innovazione sociale/Projects of Social Enterprise as Strategies of Urban Regeneration: Methods and Spaces for Social Innovation. Euricse Work. Pap. 2012, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ostanel, E. Spazi Fuori dal Comune. Rigenerare, Includere, Innovare; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Venturi, P.; Zandonai, F. Dove. La Dimensione di Luogo che Ricompone Impresa e Società; Egea: Milan, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Campagnoli, G. Riusiamo l’Italia: Da Spazi Vuoti a Start-Up Culturali e Sociali; Gruppo 24 Ore: Milan, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschinelli, R. (Ed.) Gli Spazi del Possibile. I Nuovi Luoghi Della Cultura e le Opportunità Della Rigenerazione; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Centro Studi Fondazione CRC. Rigenerare Spazi Dismessi. Nuove Prospettive per la Comunità; Quaderni della Fondazione CRC: Cuneo, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://www.fondazionecrc.it/index.php/analisi-e-ricerche/quaderni/405-quaderno-37 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Bartolozzi, C.; Dabbene, D.; Novelli, F. Adaptive reuse di beni architettonici religiosi. Restauro e inclusione sociale in alcuni casi studio torinesi. BDC 2019, 19, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, L.M.; Sokolowski, S.W. Beyond Nonprofits: Re-conceptualizing the Third Sector. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2016, 27, 1515–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libera. Fattiperbene. Il Riutilizzo Sociale dei Beni Confiscati in Italia. Numeri, Esperienze e Proposte; Multiprint: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.libera.it/schede-1573-fattiperbene (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Available online: http://www.anci.it/wp-content/uploads/Protocollo-Intesa-MLPS-ANBSC-AGD-ANCI-28-novembre-2017.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Available online: https://anci.lombardia.it/documenti/8206-documento%20riuso%20patrimonio%20cultura%20.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Novelli, F. Buone pratiche di conservazione e valorizzazione a rete del patrimonio architettonico religioso alpino il territorio tra Valle Elvo (BI) e Canavese Montano (TO). IN_BO. Ricerche e Progetti per il Territorio, la Città e L’Architettura 2016, 7, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, L.; Longhi, A.; Segre, G. Il patrimonio culturale e paesaggistico per lo sviluppo locale: Il bando della Compagnia di San Paolo (2012–2014). In Proceedings of the Conference on Cultural Heritage. Present Challenges and Future Perspectives, Rome, Italy, 21–22 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Errante, E. Patrimonio Culturale e Paesaggio. Il Ruolo delle Fondazioni Bancarie nel Sostegno alle Politiche di Valorizzazione del Territorio: L’esperienza del Bando della Compagnia di San Paolo “Le risorse culturali e paesaggistiche del territorio: Una valorizzazione a rete”. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meneghin, E. Il patrimonio culturale e paesaggistico nelle strategie di sviluppo locale: Progettualità nelle aree interne di Piemonte e Liguria. In Proceedings of the Conference SIU DOWNSCALING, RIGHTSIZING. Contrazione demografica e Riorganizzazione Spaziale, Turin, Italy, 17–18 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S.; Oteri, A.M. (Eds.) Programmazione e finanziamenti per la conservazione dell’architettura. In RICerca/REStauro; Fiorani, D., Scient. Coord. Sezione 2 Programmazione e Finanziamenti; Quasar: Rome, Italy, 2017; pp. 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bosone, M.; De Toro, P.; Fusco Girard, L.; Gravagnuolo, A.; Iodice, S. Indicators for Ex-Post Evaluation of Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse Impacts in the Perspective of the Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, S.; Venturi, P.; Rago, S. Valutare l’impatto sociale. La questione della misurazione nelle imprese sociali. Impresa Sociale 2015, 6, 76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mohaddes Khorassani, S.; Ferrari, A.M.; Pini, M.; Settembre Blundo, D.; García Muiña, F.E.; García, J.F. Environmental and social impact assessment of cultural heritage restoration and its application to the Uncastillo Fortress. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 1297–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horizon 2020 Project CLIC: Circular Models Leveraging Investments in Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse. Available online: https://www.clicproject.eu/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- OpenHeritage: Organizing, Promoting and ENabling Heritage Reuse through Inclusion, Technology, Access, Governance and Empowerment. Available online: https://openheritage.eu/oh-project/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Ministero della Cultura. Available online: https://www.beniculturali.it/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Direzione Generale Creatività Contemporanea. Available online: https://creativitacontemporanea.beniculturali.it/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Osservatorio Online per il Riuso di Spazi a Fini Creativi, Artistici e Culturali. Available online: http://www.osservatorioriuso.it/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Agenzia del Demanio. Available online: https://www.agenziademanio.it/opencms/it/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Infobandi CSVnet. Available online: https://infobandi.csvnet.it/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Forum Nazionale del Terzo Settore. Available online: https://www.forumterzosettore.it/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Cantiere Terzo Settore. Available online: https://www.cantiereterzosettore.it/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Italia Non Profit. Available online: https://italianonprofit.it/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Labsus—Laboratorio per la Sussidiarietà. Available online: https://www.labsus.org/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Excursus Plus. Available online: https://www.excursusplus.it/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Legislative Decree 42/2004, Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio. Available online: https://web.camera.it/parlam/leggi/deleghe/04042dl.htm (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Dezzi Bardeschi, C. (Ed.) Abbecedario Minimo Ananke. Cento Voci per il Restauro; Altralinea Edizioni: Florence, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/222527 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Coscia, C. The Ethical and Responsibility Components in Environmental Challenges: Elements of Connection between Corporate Social Responsibility and Social Impact Assessment. In Corporate Social Responsibility; Orlando, B., Ed.; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.; Nicholls, J.; Paton, R. Measuring Social Impact. In Social Finance, Nicholls, A., Paton, R., Emerson, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 253–281. [Google Scholar]

- Coscia, C.; Rubino, I. Fostering New Value Chains and Social Impact-Oriented Strategies in Urban Regeneration Processes: What Challenges for the Evaluation Discipline? In New Metropolitan Perspectives. Knowledge Dynamics and Innovation-Driven Policies Towards Urban and Regional Transition; Bevilacqua, C., Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camoletto, M.; Ferri, G.; Pedercini, C.; Ingaramo, L.; Sabatino, S. Social Housing and measurement of social impacts: Steps towards a common toolkit. Valori E Valutazioni 2017, 19, 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- ASVIS. I Territori e gli Obiettivi di Sviluppo Sostenibile. Rapporto ASVIS 2020. 2020. Available online: https://asvis.it/rapporto-territori-2020/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- OECD. Principles for the Evaluation of Development Assistance; DAC Development Assistance Committee: Paris, France, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, D. Counterpreservation. Architectural Decay in Berlin Since 1989; Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Costa, M. Il Progetto di Restauro per la Conservazione del Costruito; Celid: Turin, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lichfield, N.; Kettle, P.; Whitbread, M. Evaluation in the Planning Process: The Urban and Regional Planning Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Zampini, A. Il ruolo delle fondazioni bancarie nei processi di valorizzazione del patrimonio architettonico. In RICerca/REStauro; Fiorani, D., Scient. Coord. Sezione 2 Programmazione e Finanziamenti; Della Torre, S., Oteri, M.A., Eds.; Quasar: Rome, Italy, 2017; pp. 288–297. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S. Conservazione programmata: I risvolti economici di un cambio di paradigma/Planned conservation: The economic implications of a paradigm shift. Il Capitale Culturale 2010, 1, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medici, S.; De Toro, P.; Nocca, F. Cultural heritage and sustainable development: Impact assessment of two adaptive reuse projects in Siracusa, Sicily. Sustainability 2020, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Della Spina, L. Adaptive sustainable reuse for cultural heritage: A multiple criteria decision aiding approach supporting urban development processes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Field Name | Field Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Call name | Qualitative | Name of the call |

| Promoter name | Qualitative | Name of the promoter |

| Promoter category | Qualitative | Legal status of the promoter (public, private, private nonprofit, mixed public private, etc.) |

| Promoter subcategory | Qualitative | Specific classification of the promoter (central administration, local administration, foundation of banking origin, business foundation, etc.) |

| Promoter geographical location | Quantitative | Registered office of the promoter |

| Latitude, longitude | Quantitative | Geographical coordinates of promoter’s registered office |

| Deadline for call | Qualitative | Maximum deadline for submission of applications for proposing entities |

| Recipient category | Qualitative | Legal status of the recipient of the call (public, nonprofit, private, etc.) |

| Type: geographical scope of validity | Qualitative | Geographical scope of application of the call (national, regional, provincial, etc.) |

| Name: geographical scope of validity | Qualitative | Name of geographical scope of application of the call |

| Overall budget | Quantitative | Maximum amount made available by the promoter (EUR) |

| Budget per project | Quantitative | Amount made available by the promoter for each project (EUR) |

| Architectural heritage categories | Qualitative | Categories of architectural heritage of the call (religious architectural heritage, rural, etc.) |

| Thematic areas | Qualitative | Actions on the architectural heritage financed by the call (conservation, reuse, enhancement, etc.) as defined by current legislation [109] and existing literature [110] |

| Brief description | Qualitative | Call description, evaluation criteria of the proposers and expected impacts |

| Field Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Macro-dimension | Macro-category of impact of the indicator (material living condition/quality of life/social cohesion) |

| Micro-dimension | Micro-category of impact of the indicator (BES) |

| Indicator | Description of the indicator |

| Output/outcome | Time dimension of the expected results |

| Typology | Nature of the indicator (qualitative if based on subjective and unquantifiable aspects and quantitative if based on precisely measurable aspects) |

| Stakeholder | Beneficiary of the expected results |

| Source | Literary source of the indicator |

| Cluster | Call Name | Name of the Promoter | Call Editions | Recipient Entity Category | Name Geographical Scope of Validity | Overall Budget | Budget per Project | n. Funded Projects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Culturability | Fondazione Unipolis | 2014–2015 | Nonprofit | Italy | 360,000 EUR | 60,000. EUR | 6 |

| A | Culturability | Fondazione Unipolis | 2016 | Nonprofit | Italy | 400,000 EUR | 50,000 EUR | 5 |

| A | Culturability | Fondazione Unipolis | 2017 | Nonprofit | Italy | 400,000 EUR | 50,000 EUR | 5 |

| A | Culturability | Fondazione Unipolis | 2018 | Nonprofit | Italy | 300,000 EUR | 50,000 EUR | 6 |

| A | Culturability | Fondazione Unipolis | 2020 | Nonprofit | Italy | 600,000 EUR | 145,000 EUR | 4 |

| A | Luoghi comuni. Diamo spazio ai giovani | Regione Puglia | 2018–2020 | Public/nonprofit | Apulia | 7,000,000 EUR | 40,000 EUR | 19 |

| B | Valore Paese—Cammini e Percorsi | Agenzia del demanio | 2017 | Profit/nonprofit | Italy | 0.00 EUR [109] | 0.00 EUR | 13 |

| B | Beni aperti | Fondazione Cariplo | 2018 | Public/nonprofit | Lombardy/Verbano Cusio Ossola/Novara | 6,000,000 EUR | 500,000 EUR | 17 |

| B | Beni aperti | Fondazione Cariplo | 2019 | Public/nonprofit | Lombardy/Verbano Cusio Ossola/Novara | 6,000,000 EUR | 500,000 EUR | 14 |

| C | Emblematici Provinciali—focus “Beni comuni” | Fondazione Cariplo and Fondazioni di Comunità | 2016 | Nonprofit | Lombardy/Verbano Cusio Ossola/Novara | not specified | min 50,000 EUR (minimum project cost 100,000 EUR) | 8 |

| C | Emblematici Provinciali—focus “Beni comuni” | Fondazione Cariplo and Fondazioni di Comunità | 2017 | Nonprofit | Lombardy/Verbano Cusio Ossola/Novara | not specified | min 50,000 EUR (minimum project cost 100,000 EUR) | 7 |

| C | Emblematici Provinciali—focus “Beni comuni” | Fondazione Cariplo and Fondazioni di Comunità | 2018 | Nonprofit | Lombardy/Verbano Cusio Ossola/ Novara | not specified | min 50,000 € (minimum project cost 100,000 EUR) | 7 |

| C | “Il bene torna comune” | Fondazione con il Sud | 2014 | Nonprofit | Basilicata/Calabria/Campania/ Apulia/Sardinia/Sicily | 4,000,000 EUR | 500,000 EUR | 7 |

| C | “Il bene torna comune” | Fondazione con il Sud | 2017 | Nonprofit | Basilicata/Calabria/Campania/Apulia/Sardinia/Sicily | 4,000,000 EUR | 500,000 EUR | 7 |

| C | Santuari e Comunità. Storie che si incontrano | Fondazione CRT | 2018–2020 | Ecclesiastical body/partnership with nonprofit | Piedmont/Valle D’Aosta | 4,000,000 EUR | 250,000 EUR | 16 |

| Macro-Dimension | Micro-Dimension | Stakeholder | Indicator | Rating Scale * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material living conditions | Economic well-being | Public producers on-site/Private producers on-site | Economic/financial self-sustainability of the asset | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Material living conditions | Economic well-being | Private producers on-site | Attraction of funding sources (private capital, crowdfunding, and tax credit) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Material living conditions | Economic well-being | Private producers on-site | Attraction of investments at the local level (local banks, ethical banks, and foundations) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Material living conditions | Economic well-being | Public producers off-site/Private producers off-site/Consumers off-site | Reinvestment of profits in social impact actions | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Material living conditions | Economic well-being | Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Increase in the number of visitors/tourists | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Material living conditions | Economic well-being | Consumers off-site | Increase in real estate values in the area | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Material living conditions | Economic well-being | Private producers on-site/Private producers off-site | Increase in revenues from activities in the area (construction, culture and creativity, tourism, trade, education and training, research and innovation, etc.) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Material living conditions | Economic well-being | Private producers on-site/Private producers off-site | Establishment of new activities in the area (culture and creativity, tourism, trade, etc.) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Material living conditions | Economic well-being | Consumers off-site | Increase in the number of residents in the area | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Material living conditions | Work and work/life balance | Private producers on-site/Private producers off-site/Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Creation of new jobs (direct, indirect and induced) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Environment | Private producers on-site/Private producers off-site/Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Use of bio-eco-compatible materials (materials with a high content of recycled components, local materials, materials of natural origin, certified materials), bioclimatic techniques and devices, and use of greenery | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Environment | Private producers on-site/Private producers off-site/Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Sustainable management of the construction site (use of dry technologies, reuse of waste materials, reduction of waste disposal in landfills, containment of noise and air pollution) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Environment | Private producers on-site/Private producers off-site/Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Energy saving (improvement of energy class, use of renewable energy sources, energy-saving systems, systems and plants with improved characteristics compared to current legislation) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Subjective well-being | Private producers on-site/Private producers off-site/Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Increase in subjective well-being connected to the reuse of the good and the preservation of the spirit of the place | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Innovation, research and creativity | Private producers on-site | Activation of new projects in the spaces following the reuse of the asset | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Innovation, research and creativity | Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Increase in cultural activities and events offered | −2,−1,0,+1,+2 |

| Quality of life | Education and training | Public producers on-site/Private producers on-site/Public producers off-site/Private producers off-site | Increase of intellectual capital through the activation/strengthening of skills, innovation and participation | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Education and training | Public producers on-site/Private producers on-site/Public producers off-site/Private producers off-site | Communication, dissemination and transfer of design and managerial skills | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Education and training | Consumers on-site | Improvement of the level of education and training of users/visitors | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Landscape and cultural heritage | Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Increased awareness of the architectural heritage and active social protection (percentage (or number) of users/visitors who express willingness to pay for the conservation of the asset) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Landscape and cultural heritage | Public producers on-site/Public producers off-site | Inclusion of the property in the lists of assets bound in accordance with current protection legislation (Legislative Decree 42/2004, Regional Landscape Plan, local legislation, etc.) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Landscape and cultural heritage | Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Promotion of actions aimed at fostering the conservation of the asset according to a processuality of the intervention phases (knowledge, maintenance/restoration/prevention, reuse, and enhancement) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Landscape and cultural heritage | Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Compatibility of reuse with the preservation of tangible and intangible values of the asset | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Landscape and cultural heritage | Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Promotion of actions aimed at fostering the planned conservation of the asset | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Landscape and cultural heritage | Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Promotion of actions to improve access to tangible and intangible resources | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Landscape and cultural heritage | Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Promotion of actions aimed at fostering the social recognition of new assets | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Quality of services | Consumers off-site | Increase in services in the area (avoiding gentrification, touristification, and congestion) | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Health | Consumers off-site | Increased cleanliness and healthiness of the area | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Safety | Consumers off-site | Increased area security | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Quality of life | Safety | Consumers off-site | Increased perception of security in the area | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Social cohesion | Social connections | Private producers on-site/Private producers off-site | Construction of a network (national/international) with other private profit or nonprofit organisations for the co-design and co-creation of activities and for the exchange of good practices, knowledge, and innovative approaches | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Social cohesion | Social connections | Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Increase in social inclusion (minorities, migrants and other disadvantaged groups) through the activation of new employment contracts and participation in initiatives and projects of social utility | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Social cohesion | Social connections | Consumers on-site/Consumers off-site | Increase civic pride, sense of belonging, and awareness of heritage | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Social cohesion | Social connections | Private producers on-site/Private producers off-site | Activation/strengthening of an active civil society (heritage community) that shares a common interest in the good | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Social cohesion | Politics and institutions | Public producers on-site/Public producers off-site | Activation/strengthening of collaborations/partnerships/conventions with public institutions for the care of the asset | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

| Social cohesion | Politics and institutions | Public producers on-site/Public producers off-site | Economic savings for public institutions related to reuse and planned conservation of the asset | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dabbene, D.; Bartolozzi, C.; Coscia, C. How to Monitor and Evaluate Quality in Adaptive Heritage Reuse Projects from a Well-Being Perspective: A Proposal for a Dashboard Model of Indicators to Support Promoters. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127099

Dabbene D, Bartolozzi C, Coscia C. How to Monitor and Evaluate Quality in Adaptive Heritage Reuse Projects from a Well-Being Perspective: A Proposal for a Dashboard Model of Indicators to Support Promoters. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127099

Chicago/Turabian StyleDabbene, Daniele, Carla Bartolozzi, and Cristina Coscia. 2022. "How to Monitor and Evaluate Quality in Adaptive Heritage Reuse Projects from a Well-Being Perspective: A Proposal for a Dashboard Model of Indicators to Support Promoters" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127099