1. Introduction

The way we produce and distribute food is at the heart of some of the main global challenges. In 2014, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) reported that the global efforts to combat hunger and malnutrition had been exhausted [

1]. Despite current advances in food production and the growth of international trade, the FAO estimates that in 2020, between 720 and 811 million people in the world faced hunger, mainly in Africa (21%), Asia (9%), and Latin America and the Caribbean (9%) [

2]. The Hunger Map of the World Food Program added that, in 2020, 768 million people were chronically

undernourished, defined as people who are not able to meet food consumption requirements in the long term. Currently, most of the international organizations monitoring hunger agree that this scenario will become worse: the WFP estimates that in 2022, around 871 million people across 92 countries will still lack sufficient food consumption [

3].

In 2019, the Lancet Commission on Obesity report, entitled The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change, expanded on this perspective with a warning that we are facing three simultaneous pandemics: undernutrition, obesity, and climate change [

3]. Malnutrition is today one of the leading causes of poor health globally. Similarly, climate change effects are also endangering both the health of people and nature. The synergy between these pandemics forms a global syndemic, the main drivers of which are food and agriculture, transportation, and land use [

4].

In general, most of these studies agree that the solutions to the current crisis involve the transformation of current food systems, which includes all actors, institutions, and norms related to the production, distribution, and consumption of food, including its main economic, health, and environmental impacts. Even though we are achieving record levels of food production, we are failing to guarantee the right to access food and the right to protect nature [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Hegemonic and conventional food systems are associated with industrialized and global production and marketing chains, as well as the free circulation of ultra-processed products. This system is connected to the main problems we face today (huge inequalities, malnutrition, hunger and obesity, and environmental damages). On the other hand, Sabourin et al. relate alternative food systems to the centrality of the spatial or territorial dimension [

5]. Territorialized food systems force us to put the dynamic interaction between territory and society, agriculture, and food at the centre of our analysis. Similarly, the High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE) of the United Nations stresses that the transformation of our food system will depend on neither a single formula nor standardized solution, but on the construction and amplification of solutions rooted in each territorial context [

5] in a bottom-up movement. HLPE highlights the importance of supporting shorter production chains (bringing production closer to consumption) and focusing on territorial markets [

5]. Territorial markets (in which territorial food systems are included) are shaped around local ingredients and resources and built by territorial actors and institutions [

6]. These markets have the potential to expand opportunities for small farmers to contribute resources and aid in landscape conservation, as well as to endow territorial actors with greater agency. The State plays a central role in enforcing territorial markets through innovative rural development public policies that promote alternative production–consumption circuits.

This paper reflects on how the territorial approach (extensively promoted by the State in Latin America countries in the 21st century) can be collaboratively used to strengthen territorial food markets that are more autonomous, sustainable, and connected with nature and territorial resources. The paper’s objective briefly analyses the Latin American experience of territorial development (through a literature review) and investigate a concrete (and recent) case of territorial development in Brazil, aiming to explore how territorial development can contribute to strengthening territorialized and more localized food systems that have greater resilience in the face of adversity. The experience of the Borborema Territory, illustrated in this paper, suggests that territorial development processes endow territorial actors with the ability to react to deterritorialization drivers and to reinforce territorial markets and a territorial project of rural development. By placing territory, resources, and territorial actors and institutions at the core of rural development strategies, territorial development reinforces territorialized food systems centred in small circuits of production–consumption. These alternative food systems not only contribute to social and environmental sustainability but enhance territorial development by expanding opportunities for territorial actors, diversifying territorial economy, and creating more crisis-resilient territories.

In our research, we employed a thematic and selective literature review [

7], the analysis of secondary indicators, and conducted online interviews [

8]. Our analysis focuses on the Latin American case, one of the most advanced areas for territorial development policies. We situate our research in the Borborema Territory (Paraíba, Brazil), which is a significant case study for understanding the dynamics of territorialization (and deterritorialization) of agroecological production systems in Brazil.

In the second section of the paper, some remarks on the research methodology are presented. In order to support the discussion, in the third section, a short literature review regarding the territorial approach to rural development in Latin America since the 2000s is conducted. It is a review that is selective in order to not exhaust the extensive literature on rural territorial development approaches, instead focusing mainly on the research output produced by the Observatory of Public Policies for Agriculture (OPPA) of the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ) and by other experts, especially Latin Americans. The review is also thematic and focusses on the discussion of a few topics that are part of the interpretative framework of the territorial approach that are emblematic of the type of perspective that we are using on the territorial approach in this paper. To contextualize the Brazilian case, a focus is made on the critical balance of three major axes that are central to reflecting on territorial development: territorialization of governance and social management of territories, territorialization, and articulation (articulação in Brazilian Portuguese refers to the collective process through which social actors come together with ideas, resources, interests, and information to implement public policies) of Public Policies; Territorialization, Markets, and Sustainability. In item 4, the Borborema Territory is presented to contextualize the case study on which our analysis is based. As a result of this selective literature review, we apply in our analysis the three dimensions of our aforementioned theoretical framework: (i) The union hub, the democratization of governance, and the strengthening of social management; (ii) territorialization of public policies and resilience in the face of the dismantling of territorial development promotion instruments; and (iii) supermarkets, new commercialization channels (farmers’ markets and produce shops), and the democratization of access to natural resources (water and seeds). We close this paper with a few conclusions.

2. Methodology

This article is the result of the research project “Literature Review, Assessment and Strategy for Work on Territorial Development and Poverty Eradication”. It results from a partnership created in 2019 by FAO-Rome, the Consultancy and Services for Alternative Agriculture Projects (AS-PTA), and the Graduate Program in Social Sciences in Development, Agriculture and Society (CPDA) of the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ). Its objective was to further reflect on territorial development and the eradication of poverty anchored in the Borborema Territory [

8]. The methodology combined a thematic and selective bibliographic review on topics related to territorial development in Latin America (next section) and in the Borborema Territory with secondary data collection and field research [

7,

8]. It is important to stress that the interviews/field research occurred during the lockdown measures implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, forcing us to switch our fieldwork to online interviews conducted with digital technologies such as emails, conference calls (Skype, Google Meet, Zoom), WhatsApp, etc. We chose the means of communication based on the interviewee’s preferences and the conditions of access (technology, internet, phone access, etc.). The methodology comprised three stages:

- (i)

A series of secondary data to characterize the Territory of Borborema (socioeconomic, demographic, and environmental data), as well as to understand the main transformations undergone in the territory in recent years;

- (ii)

Twelve in-depth interviews with representatives of international institutions, such as FAO and the Latin America Center for Rural Development—RIMISP; Brazilian, European, and Latin American academics and researchers; national and territorial leaders, politicians, and ex-politicians; managers involved in territorial development initiatives and social movements; and family farmers, among others. A semi-structured guide was applied when interviewing Brazilian and foreign specialists on territorial development in the first semester of 2020. We aimed to identify the main gaps in recent studies on territorial development;

- (iii)

A focus on the Borborema Territory in the first semester of 2020 through the use of three different surveys.

The first was a battery of 20 online interviews (using a semi-structured guide) with leaders of smallholder producers (2); members of municipal governments (3); agrarian reform settlers (4); members of women’s movements (2); and the youth committee and other thematic committees of the Borborema Union Pole (Seeds and Health and Food), as well as leaders of Rural Workers Unions (9). With representatives from the municipalities of Remígio, Lagoa Seca, Campina Grande, Massaranduba, Queimadas, Solânea, and Alagoa Nova, the interviews mapped the main territorial food systems and also investigated the impact of the pandemic on the territorial food system. We finished by exploring future prospects for the territory in the post-COVID-19 context.

In the second survey, since the pandemic and social isolation measures were considered an important force of deterritorialization in the Borborema Territory, an electronic form was developed in order to map the main experiences that territorial actors implemented to overcome the effects of the pandemic on the territory and to build more resilient and sustainable food systems. Four initiatives were mapped: A network of agroecological farmers’ markets (Solânea, Casserengue, Arara, Remígio, Esperança, Areial, Alagoa Nova, Lagoa Seca, Massaranduba, and Campina Grande); a network of agroecological producer shops (Queimadas, Arara, Remígio, Esperança, and Solânea); donation of baskets (Arara, Areial, Casserengue, Alagoa Nova, Lagoa Seca, Esperança, and Remígio); and reactivation of the National Food Program during the pandemic (Remígio) [

9].

In the third survey, we organized two online workshops on territorial development (focus groups with 20–25 participants from nine different municipalities: Solânea, Casserengue, Arara, Remígio, Esperança, Areial, Alagoa Nova, Lagoa Seca, and Massaranduba) with leaders of smallholder producers, agrarian reform settlers, and members of women’s movements. In these groups and interviews, special attention was given to ensure the diversity of gender, generations, and insertion in the territory. Based on the participation of these actors and meeting diversity criteria, we selected five participants: one political actor (former mayor and currently a state deputy), one settler and representative of the women farmers’ movement “As Margaridas”, one agrarian reform settler and current president of the Rural Workers Union of Remígio, one agricultural woman representing the Union Pole, and one representative of the youth group. This group gave us a broad and in-depth perspective about the development processes in the Borborema territory. With these in-depth online interviews, mostly with representatives from Campina Grande, Remígio and Lagoa Seca, we aimed to understand the recent trajectory of territorial development in order to map the main initiatives implemented during the pandemic and also to reflect on the future perspectives.

In our theoretical framework we assume territorial development as the process in which territorial actors can advance the territorialization of an autonomous rural development project that is focused on the territory’s resources and institutions. Contrary to the Latin American experience that has prioritized territorialization conducted by government initiatives and the territory as a planning unit, our theoretical framework offers a broader view of territorialization/deterritorialization processes and its connections to territorial development. We highlight territorialization forces performed by civil society actors (family farmers, traditional peoples and populations, social movements and organizations, NGOs, etc.) that strengthen productive systems connected with the territory and reinforce territorial identities (e.g., territorial food systems). We also stress the relevance to recognizing a kind of (de)territorialization promoted by large corporations that promote global food systems (and, thus, compete with other territorial projects). We especially stress extractive industry, for which a territory is merely a market of natural resources and an asset reserve (private territorialization). The deterritorialization imposed by such corporations, in our view, was identified as having the opposite “visions of the future” advocated for civil society, together with devasting social, economic, and environmental effects. Finally, in our methodology, we emphasize the complexity and the challenging task of identifying ongoing territorialization and deterritorialization processes. We sought to understand what we call territorialization and deterritorialization processes by consulting different sources: collecting and systematizing different academic works (e.g., papers and book chapters); consulting reports, booklets, and manuals; selecting secondary data; and consulting different territorial leaders and institutional representatives that make up the territorial network (AS-PTA, local union, ASA, etc.).

In this paper, our hypothesis is that territorial development increases territories’ resilience by strengthening territorial food markets and providing territorial actors with better capacities to face the current main challenges of rural development [

8]. The main reasons for that are: (1) the previous existence of shared experiences (territorial and solidarity networks) that favour innovation and stimulate the creation of territorialized production systems; (2) the previous accumulation of public policies at different levels, empowering local social actors, and promoting more inclusive and sustainable productions patterns; and (3) the capacity of territorial actors to assume a leading role in the development process and in building more resilient territorial institutions. The main questions that mobilize us are: What are the main lessons we can learn from recent territorial development experiences in Latin America? How can the territorial development approach contribute to overcoming the main challenges of rural development and to strengthening territorial food systems?

The case study of the Borborema Territory was chosen for two reasons. Firstly, we stress the previous existence (in Brazilian and Latin American studies) of an extensive documentation about this territory and its relation to rural development dynamics, territorial experiences, and social networks. Secondly, due to its recent trajectory, we noticed the existence of a dense actors’ network oriented towards the construction of localized food systems and territorial development in the region. Therefore, Borborema was identified as an emblematic case to discuss the territorial development approach and its potential to strengthen a territorial food system in a context in which powerful forces of deterritorialization are at work.

3. Results 1: Thematic and Selective Literature Review on Territorial Development in Latin America

Considering Latin America, Berdegué, Christian, and Favareto highlight that a territorial development approach was the main analytical framework for rural development in the first two decades of the 2000s [

10]. Territorial development soon entered the agenda of international organizations. One of the milestones was the creation of the territorial division of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 1994, and the release of the World Bank report “The New Vision of Rural Development” in 1996 [

11]. In 2002, the World Bank prioritized rural development strategies that overcame the sectoral approach, and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) elaborated on the concept of a territorial approach to rural development [

12]). Then, in a period when Latin American economies were increasingly adopting a neoliberal agenda while experiencing a democratic transition, new issues entered the rural development agenda including changes in the role of the State, demands for decentralization, the expansion of transnational value chains, increasing criticism of the Green Revolution, the prominence of the environmental concerns, and the persistence of rural poverty [

10,

11,

12,

13]. These reflections, among others, culminated in the search for new approaches to rural development, broadening its scope and differentiating it from the traditional sectoral conception of agricultural and agrarian development [

12,

14,

15,

16].

In developed countries, the new approaches sought to overcome the productivist agricultural model (based on the logic of the Green Revolution) and trade conflicts between Europe and the United States, resulting in the recognition of new roles for agriculture and the rural realm in contemporary society (multifunctionality) [

11]. Latin America required new approaches that could contemplate issues such as the persistence of poverty and its multidimensionality; the strengthening of family farming and small non-agricultural enterprises; the recognition of the multifunctional character of agriculture and of rural families’ pluriactivity; the growing importance of relations between rural and urban contexts; and the incorporation of the specifics of each location [

12,

16,

17]. Territorial approaches then turned towards: (i) eradicating rural poverty [

18]; (ii) promoting the protagonism of the territory’s social actors [

7,

13,

18]; (iii) positioning the territory as a reference unit [

19]; (iv) seeking environmental sustainability [

17]; (v) promoting agricultural and non-agricultural jobs [

16,

17]; (vi) emphasizing intersectoral (agricultural, industrial, and service) and multidimensional (productive, institutional, and socio-environmental) relations [

16,

17]; (vii) valuing rural–urban bonds [

16,

17]; and (viii) recognizing the importance of institutional arrangements rooted in territories [

12,

19,

20,

21].

In a 2004 paper, Schjetman and Berdegué deemed territorial development as the productive and institutional transformation of a rural space aimed at ending rural poverty [

12]. Leite et al. recognize this potential, but also highlight its capacity to energize the territorial economy through strategies to strengthen family farming and territorial markets [

17]. In this case, territory becomes a political category, associated with the empowerment of family farming and territorial food systems.

In the last decade, countless experiences of territorial development have taken shape in Latin America: in Mexico with the Sustainable Rural Development Law; in Bolivia with the Popular Participation Law and the Decentralization Law; in Colombia with the Integrated Rural Development Fund; in Ecuador with the Local Sustainable Development Project (PROLOCAL); and in Brazil with the National Sustainable Rural Development Plan (in 2001) [

13,

21]. The Brazilian experience was one of the most advanced in the design of territorial policies focused on family farming and combating rural poverty, with the creation of a Secretariat for Territorial Development (in 2003), under the former Ministry of Agrarian Development (MDA), and the subsequent Policy for the Sustainable Development of Rural Territories (PDSTR, in 2004) and Citizenship Territories Program (PTC, in 2008) [

17,

18,

19,

22,

23].

In general, despite the different understandings and definitions of territory, almost all approaches emphasize the strategic nature of the territorial scale within the scope of public policies that seek (a) socioeconomic rebalancing; (b) environmental management; (c) building a new competitive capacity; and (d) governance reform [

17,

19]. Territory is considered the operational category that guides and instructs the State’s actions in intermediate spaces (for example, of meso- and micro-regional character) [

19]. In Latin American experiences, territory has been commonly associated with the area delimited by the collective action of social actors who share identities and/or a common representation of reality [

21]. It thus becomes a political category and the space for collective action by social actors who seek to formulate and implement proposals for territorial self-government and to participate in and influence public actions. Although they intended to break with the insufficiency of more traditional scales (such as municipality or district), in many cases the operationalization of the territorial policy came up against the lack of recognition of the territory as an administrative unit in the federative structures. It limits its ability to acquire and manage public resources (which is a decisive obstacle in the Brazilian case).

From this brief contextualization and taking into account the recent experiences of territorial development policies, with a special focus on the Brazilian case [

7,

8], we highlight three main dimensions of territorial development that guide our analysis of the Borborema Territory.

3.1. Territorialization of Governance and Territorial Social Management

The territorialization of governance is understood as the processes, arenas, and institutional arrangements implemented by government initiatives to carry out the decentralization and democratization of public action and management. One of its important dimensions is the creation of arenas and public spaces in the territory geared towards social participation, with the inclusion of social actors that are usually excluded (social movements, social organizations, associations, etc.). In the case of Latin America, this took place in an ambiguous context: progress was being made towards re-democratization (from the second half of the 1980s onwards) at the same time that the neoliberal logic was growing. The spaces for social participation were crossed, so to speak, by two distinct and contradictory projects: a democratizing project, which fostered decentralization and the State’s protagonism, and a neoliberal project, which associated decentralization with the hollowing out of State initiative [

17].

As a result, it was not uncommon to observe excessive fragmentation and multiplication of participation spaces and the transfer of certain State responsibilities and functions to civil society without adequate support to qualify and enable this participation. Some authors point out that the consolidation of public spheres and the decentralization of decision-making power (from the bottom up) depend on complementary public actions aimed at improving participation [

13,

17], as well as an effort to organize these spaces and policies around a “territorial development project” [

17].

The territorialization of governance is associated with social management, understood as the expansion of citizen participation in the management of public policies and in strategic decision-making in the territory [

17,

20]. It often depends on the protagonism of certain social actors and their ability to organize and mobilize other actors around ideas and socially aggregating proposals. One challenge is that situations characterized by conflicts and negotiations of interests (with different—and contradictory—values) tend to encourage rent seeking initiatives, when individuals try to appropriate the “income” created by State policies [

22].

The greater or lesser protagonism depends on leadership development and the existence of ideas, practices, and experiences (technical, economic, social, political, etc.) that allow territory leaders to formulate, at least approximately, some kind of strategic proposal such as a “vision for the future”, common agenda, or project for rural development in the territory. Generally, this protagonism depends on neither “technical formulas” produced in manuals on the territorial development approach nor on best practices—although these can be important sources of inspiration and learning. Rather, it depends on (1) a well-structured conception of politics; (2) the early history and economic, social, and cultural characteristics of the territory, as well as the power structure and existing resources in the territory; (3) the type of actors present (civil society, market, and State) and the type of interests they have in the territory; and (4) the capacity to mobilize existing social networks inside and outside the territory. Nothing guarantees, in advance, that the strengthening of a territorial rationale will result in a common territorial development strategy.

3.2. Territorialization and Articulation of Public Policies

Territorial development relates to the search for greater efficiency in State actions, in response to the demand for decentralization and the expansion of spaces for social participation. An important dimension of this process is the territorialization of public policies based on the realization that territories are a favourable scale for the implementation and provision of public services. They are the intermediary space between the national and the local [

18,

19]. It is in the territory that public policies and actions can converge and be self-reinforced in predetermined directions and where priority needs and demands are more easily identified. The goal of territorial development is to bring existing sectoral, differentiated, and universal policies closer to the territory; therefore, adapting it to territorial characteristics, actors, and dynamics. It also favours the monitoring and social management of public policies, which requires the creation of new arrangements, the strengthening of these participatory spaces, and the generation of information about the territory (territorialization of governance).

A key aspect of territorial development policies is the public policies’ capacity for convergence [

18,

20,

23]. More than the concentration of differentiated policies, territorialization has to do with the capacity of territorial actors (in particular, but not only, public managers) to combine different public policy instruments in order to create synergy between their different results, advancing towards the realization of a collectively conceived territorial project [

23].

3.3. Territorialization, Markets, and Paths to Sustainability

The experience of almost twenty years of using the territorial approach in Latin America has led to diversified and heterogeneous operationalization paths. At times, territorial development is seen as a means for the dynamization of rural economies; at others, it has focused on the confrontation and eradication of rural poverty [

24].

Markets, commercial transactions, and the private sector play a central role in boosting rural economies, although they have been largely neglected in territorial development research. The transformations of the agri-food system generate important effects on the possibilities of insertion and development paths of rural territories. The strengthening of a territorial project takes place in an ambiguous context in which the power and influence of large commodity chains combine, almost always in a contradictory way, with greater attention to environmental concerns and with changes in consumer preferences that favour new alternative markets associated with values based on quality, inclusion, and sustainability. These market dynamics influence more traditional channels and make way for new spaces to be explored with a strong territorial component [

25]. Sabourin et al., in a recent study, warn that the food system comprises different subsystems and food markets with distinct characteristics, based on conventional or agroecological agricultural practices; family farming, artisanal companies or large corporations; connections with global, national or regional and local chains; and the adoption of certificates and strategies on differentiated products or that bet on commodity markets. In the territory, these subsystems often coexist, but they may be interdependent, interact; or show hybrid coexistence [

6].

For certain territories, commodity markets continue to be important market-access channels with strategies varying from informal channels of entry into local markets (roadside markets, farmers’ markets, and small grocers) to cases of negotiations with supermarkets, with agro-industrial chains, and with exporting companies (traders). An important dimension of territorial development strategies, therefore, still involves strengthening agricultural markets and expanding the range of services available to support family production (credit, qualification, distribution, commercialization, etc.). Recent cases show us that in some situations, strategies of economic insertion of the territory in a systemic environment of competitiveness, such as global chains, can have exclusionary policies, thus amassing environmentally unsustainable effects. Therefore, the institutional framework and territorial development plans are paramount to ensuring measures for environmental, fiscal, or labour regulation in order to encourage the organization of integrated farmers (thus increasing their bargaining power).

In territorial development, it is important to foster alternative food productive systems and territorial production and consumption circuits, which will diversify the territory’s economy. Largely fostered by public policies, institutional markets have recently stood out, especially government purchasing and school-feeding policies. Niche markets, focused on organic and vegan foods, agroecological products, family farming products, agrarian reform products, handmade products, solidarity products, fair-trade initiatives, etc., are also important strategies. This also involves the creation of labels, certifications, and alternative points of sale. Wilkinson points out that all of these new markets are conditioned by the ability to standardize, certify, and associate products with values that go beyond the sectoral (agricultural) and productivity rationales [

25].

In this context, we observe the strengthening of new contemporary ruralities, which move away from merely productive concerns, encompassing environmental and ecosystem conservation issues (opening up to environmental services). Other ruralities include: the appreciation of culture and the struggle for the rights of indigenous peoples and other traditional peoples and communities; the reviving of more traditional production processes with deeper cultural and regional roots; the growing concerns with health and the role of food in ensuring food security and sovereignty; etc. In Latin America, these new ruralities, however, are increasingly strained by the advance of agricultural frontiers, especially in the period known as the commodities supercycle (the 2000s), where neoextractivism [

26,

27] means that new areas are increasingly incorporated into global commodity chains. This has led to the expansion of companies’ measures of territorial control and to the creation of specialized services that deal with conflicts and disputes (legal sectors, corporate social responsibility activities, and lobbies). In a context of advancing frontiers and State omission, territory is now understood by social groups (family farmers, riverbank dwellers, indigenous people, etc.) as a space of resistance and a struggle for rights and survival.

Given their enormous economic and political power and magnitude, these companies (agribusiness, mining, timber companies, among others) can count on strong support from the State and acquire an immense potential for capturing and destroying territorial dynamics. Here, we emphasize the limits and constraints that extractive corporations impose on territories when the neoliberal State weakens regulatory capacity. Such mining or agribusiness companies are not interested in discussions and negotiations regarding territorial projects, since they unilaterally design investment plans that transform the territory, operating deterritorializing projects that are based on family agriculture, local markets, and traditional peoples and communities.

Under such conditions, the territorial development policy narrative, with its emphasis on participation, governance, and inclusion of “market actors” becomes a misleading illusion [

7]. Analyses indicate that this is one of the main challenges for territorial policies. With increasing commodity prices and advancing productive frontiers, territorial policy has mostly been restricted to compensation for social groups and territories that have been adversely affected and/or that cannot be inserted into global dynamics. The rural territorial development approach became, in this sense, an “appendix” or a small “enclave” in conflict with and limited by the effects of an export-driven development strategy [

24].

Another approach to territorial development posits territory as a privileged scale for eradicating rural poverty [

18]. In general, families living in poorer rural areas suffer from precarious living conditions, have very little capacity to invest in production (and are often subject to hunger), and face barriers to accessing public services and policies. The territorial scale ideally allows for a better mapping of these families and their main restrictions and needs, while also making public policies more effective. These initiatives to address poverty must be linked to more structural measures that change the way resources are distributed in society. One of the main dimensions of poverty and inequality in Latin America is land (and natural resource) inequalities [

28,

29]. Recent experiences of territorial development in Latin America have failed to address this scenario of stark inequalities. Despite gains in the fight against hunger and in the implementation of compensatory policies, most governments have not implemented measures for the redistribution of land and the democratization of natural resources.

Currently, we stress that rural territories will continue to be pressured between environmental conservation and sustainable objectives and the need for increased commodity production. According to the FAO, in order to feed about 9.1 billion people food production will need to increase by approximately 70% (between 2005/07 and 2050) in a world increasingly beset by climate change [

30]. The future scenario is likely to be one of intensifying disputes over land and natural resources (especially water), food, energy, infrastructure, and housing. At the same time, the territory is where the closest and most direct interactions between social actors and nature take place, and where landscapes are constantly built and transformed or destroyed [

31]. The way production systems are structured in territories, therefore, plays a big role in accelerating or tackling climate change and transforming food systems. The territory, in this sense, has a strategic role in the democratization of natural resources, in the construction of new markets for biodiversity products, in the valuing and protection of traditional knowledge, and in the promotion of diversified forms of production that are more harmonious with nature’s cycles [

32,

33].

4. Results 2: Borborema Territory as a Privileged Experience of Territorial Development

The Borborema Territory is located in the Brazilian semiarid region, in the state of Paraíba, which is one of the most arid regions in the country [

32]. Historically, the north-eastern semiarid region has considerable indicators of vulnerability and poverty, as well as recurrent droughts (irregular rain patterns). The semiarid region is home to more than half of Brazil’s poor population and contributed less than 5% of the 2017 national GDP [

34].

In the Brazilian context, the semiarid region is usually considered a “problem region”, with deterministic narratives that explain poverty as caused by drought, and which defend large public policy as unique solutions [

29]. These large hydraulic construction projects concentrated only in a few locations aimed to capture, store, and transport significant volumes of water and, together with large properties, mark the land-ownership structure of the region. The poor distribution of land and water, which are essential resources for life and production, subject the most impoverished populations to situations of high vulnerability and compromise territorial development strategies [

33,

34].

The occupation of its territory is linked to large properties and to the development of a small and diversified food production agriculture -corn, beans, cassava, sweet potatoes, horticulture, and later, fruit, yellow potatoes, and coffee- (Some studies delve into Borborema Territory’s historic trajectory, see: Petersen; Caniello; Schmitt [

33,

34,

35].) Small production has remained on the fringes of large landowners who expelled small farmers from their land at times of a high commodity price cycle; during the opposite cycle, large landowners accepted—and even encouraged—the presence of small farmers who took care of and occupied the land, in a process of re-peasantization [

33,

34].

Following national agriculture in the 1950s and 1960s, the region underwent a rapid process of agricultural modernization, strengthening monocultures such as tobacco, agave, and yellow potato [

34]. The result was production specialization, with a massive replacement of local varieties—particularly beans and corn—by commercial varieties and the progressive loss of genetic heritage. This period was also marked by strong disputes placing workers and peasants against large landowners. These disputes were organized by the Rural Workers Unions (STRs) and peasant organizations (Peasant Leagues) [

35].

In the early 2000s, there was a severe drought that produced a major crisis in local agriculture, with a great effect on family farmers [

34]. The effects of deforestation and the use of chemical pesticides and inadequate soil management led to “drought periods” with increasingly longer cycles, while specialization and the progressive loss of crops’ genetic material made farmers more vulnerable [

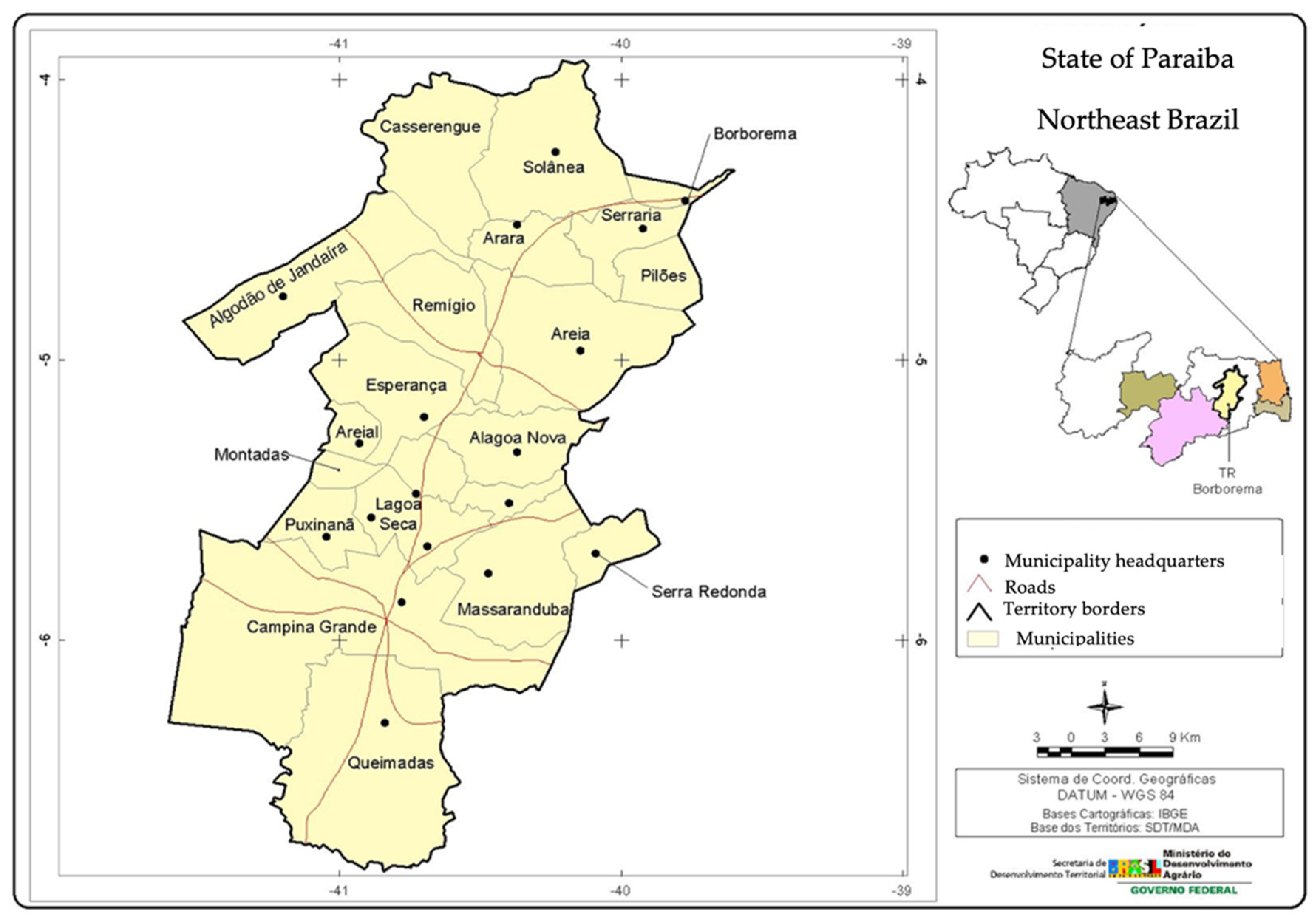

35]. During the same period, the Borborema Territory became the object of government action, through the initiative of the National Program for the Sustainable Development of Rural Territories (PRONAT) and the Citizenship Territories Program (PTC). It is important to stress that the incorporation of a territorial approach oriented to rural development by the Federal Government dates to 2003 with the creation of the Department of Territorial Development (SDT) of the Ministry of Agrarian Development (MDA), which implemented the National Program for the Sustainable Development of Rural Territories (PRONAT) and the Citizenship Territories Program, under the responsibility of the Civil House in 2008. In the specific case of the Borborema Territory, the participatory and intersectoral approach incorporated into these programs had a series of collective dynamics of social organization that, in the 1990s, would lead to the creation of the Articulation of the Paraibano Semiarid Region and the emergence of the Borborema Family Agriculture Organizations’ Union Hub. In terms of territorial policy, the Borborema Territory is made up of 21 municipalities (Alagoa Nova, Algodão de Jandaíra, Arara, Areia, Areial, Borborema, Campina Grande, Casserengue, Esperança, Lagoa Seca, Massaranduba, Matinhas, Montadas, Pilões, Puxinanã, Queimadas, Remígio, São Sebastião de Lagoa de Roça, Serra Redonda, Serraria, and Solânea [

34,

35], see

Figure 1). The Borborema Territory has many p family farmers, agrarian reform settlers, artisanal fishermen,

quilombolas (traditional communities descended from former slaves), etc. Much of the territory is rural and more than 70% of the establishments are family farms, although they occupy less than half of the total agricultural land [

36]. In addition to services, agriculture plays a major role in the economy of the Borborema Territory, with emphasis on fruit production (mandarin, orange, lime, banana, avocado, jackfruit, and

jabuticaba) and vegetable production (corn, black beans, yellow potatoes, and fava beans). Livestock farming complements subsistence and represents a kind of savings account activated in times of crisis [

35]. The main commercialization channels are the open markets and the consumer market of Campina Grande (the regional centre). The following sections describe three analytical dimensions of Borborema’s territorial development process.

4.1. The Union Hub, the Democratization of Governance, and the Strengthening of Social Management

The social and institutional experiences that were carried out in the Borborema region starting in the 1990s enabled the territorialization of a proposal for sustainable rural development model. It also represented the political construction of the Borborema Territory as a space for collective action (The analysis contained in this item is based on and adapted from: Delgado [

34]. It was also supplemented by Petersen; Schmitt; Delgado and Zimmermann; Delgado; Diniz; Piraux and Bonnal; Miranda and Piraux; Silveira, Victor, Anacleto; Bonnal, Diniz, Tonneau, Sidersky; and Petersen and Silveira [

33,

35,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].) This took place at a time of marked crisis in regional agriculture and of renewal and strengthening of rural workers’ unionism, which culminated in the creation of the Borborema Union Hub (The Hub is currently called, since 2001, the Hub for Unions and Borborema Family Agriculture Organizations) in 1998. It is a network of rural workers’ unions and family producers’ associations whose actions converge towards a collective project of territorial development based on agroecological agriculture. The network had a regional scope that goes beyond municipal limits, and which gave rise to the Agroecological Territory of the Borborema Hub (covering 14 municipalities). This organization helped promote the territory’s social fabric and enabled collective learning, thus allowing for expanding participation in territorial government policy in Brazil (in 2003) [

38].

From its beginning, the Union Hub has had a great capacity for dialogue with non-governmental organizations, such as: the Consultancy and Services for Alternative Agriculture Projects (AS-PTA) that works on the dissemination of agroecology as a model of rural development; the Coordination of the Brazilian Semiarid Region (ASA), a network that works to build popular alternatives for living with drought; and with the Agrarian Reform Settlers’ Forum. It consolidated itself as a unifying political–organizational space with great legitimacy in the territorial economy. Today, it coordinates rural workers’ unions from 14 municipalities as well as 150 community-based organizations and a regional organization of agroecological farmers, Ecoborborema, that mobilizes around 5000 farming families (30% of the existing families in the 14 municipalities of the Union Hub) [

35,

39].

This trajectory revealed a significant potential in the construction of what we call “aggregating ideas” that point to a “collective project of rural development”. It remains central to the territorial development experience in Borborema Territory. It sharply contradicts the prevailing Latin American studies that recognize advances in social participation, but verify little progress in the generation of economic and technological innovation (for a summary of the arguments presented, see, for example, Bebbington, Abramovay, Chiriboga [

46]). This tension tends to weaken the territorial approach as a strategic instrument for sustainable and democratic development. In the Borborema region, this tension is clearly present and probably always will be. However, it was possible to circumvent it through institutional and social experimentalism and the construction of two aggregating ideas: “living with the Semiarid” and “agroecological territories” [

35,

38,

39].

At a time of agricultural crises, such as soil depletion and drought, the territorial network has been able to use its political and leadership capacities to restore peasant families’ practices with their agroecosystems (heirloom seeds, crop diversification, cultivation practices, etc.), formatting them as social technologies suitable for coping with drought [

40,

41]. Experiments carried out by farmers, associated with a growing investment in the exchange of practices and technological innovations in the field of agroecology, have progressively contributed to the agroecological rural development model (see Schmitt, on which we rely verbatim on this excerpt [

35]). In parallel, another aggregating idea that has been derived is the motto of “living with the semiarid” (as opposed to “fighting drought”). The growing expertise in handling water resources and dealing with the region’s climate has culminated in the development of social technologies for capturing and storing water (concrete plate cisterns). According to Schmitt “(a) concrete plate cistern is a self-construction technique that allows, through the capture of rainwater that runs off house roofs, for the storage of 16,000 L of water each rainy season. This volume is enough to perform basic tasks (hygiene and cooking) for a family of five during eight months. Built from basic materials, an important point is that its construction is completed through the training of masons from the communities themselves. Thus, the technology is learned by the community, which then organizes to discuss cistern maintenance and strategies for their replication, forming an associative fabric that is very important for ASA’s actions” [

35]. It ended up contributing to two of ASA’s public programs that work in partnership with government agencies: the One Million Cisterns Program (P1MC) in 2003 and the One Land and Two Waters Program (P1+2) in 2007, which sought to use rainwater harvesting to democratize access to water for consumption [

33].

This continuous process of strengthening the social fabric and of political construction of the territory has increased the quality of social participation, strengthened the capacity of territorial actors in public accountability (in public decisions and public policies), democratized governance, and generated social technologies adapted to the territory [

22,

38]. This greater social protagonism shapes a two-way process: governance territorialization and social fabric strengthening in order to enhance the articulation of public policies, while public policy territorialization progressively strengthens participatory spaces and advances the implementation of the territorial project [

38,

47].

The protagonism of social actors and their capacity for agency provide the Borborema Territory with greater resilience and responsiveness when facing adverse pressure for deterritorialization [

8]. As an example, during the pandemic, social isolation measures had a strong impact on the territory’s way of doing politics, since face-to-face meetings and gatherings were prohibited [

8,

9]. However, the territory’s social actors sought to appropriate digital technologies and apps by incorporating them into their mobilization strategies. This made it possible to re-establish interaction among farmers, especially among youth and women (who suffered the most from isolation), thereby advancing the formation of a territorial communication system. The farmers themselves and their organizations create the message (connecting producers and consumers), produce the videos and ads, and devise marketing strategies. This system strengthens territorial identity and social dissemination of the role of healthy food (fresh and agroecological) in maintaining immunity, cultural traditions, and territorial resistance [

8]. This favours the maintenance of the territorial food system and leads to short production-consumption circuits even in periods where supermarket chains have advanced in the territory. These strategies, however, still come up against the low quality of internet connection in rural areas, which blocks some farmers from accessing these communication channels and limits their interactions with urban areas.

4.2. Territorialization of Public Policies and Resilience in the Face of the Dismantling of Territorial Development Promotion Instruments

From the beginning, the union movement did not act regionally. It was necessary to organize its leaders towards permanently influencing public policies and to dialogue with governments. Increasingly, the Union Hub turned to coordinating with the State, thus expanding its influence on public policies.

In the 2000s, the union movement was fuelled by the political strengthening of the Borborema Union Hub and the deepening of the political democratization process in Brazil, particularly after the election of Luís Inácio Lula da Silva’s administration in 2003 [

8,

35]. Sabourin, Craviotti, and Milhorance suggest that this movement, granted its particularities, took place in many Latin American countries, culminating in the institutionalization of family farming as a specific category in public policies [

48]. In Brazil, as described by Grisa, an important set of public policies for family farming was created by the federal government in order to foster agricultural and livestock production (for export and domestic supply), promote machinery and equipment markets, develop territories, promote food security, and improve living conditions (i.e., fighting rural poverty) [

49].

Since the 2000s, the Borborema network has had access to several differentiated public policies. Schmitt builds a timeline that summarizes the main differentiated public policies that the Union Hub has had access to [

35]): (i) the creation and implementation of the One Million Cisterns Program (P1MC); (ii) the Community Seed Banks State Program; (iii) the Rural Territorial Development Policy, with the creation of the Identity Territory of the Borborema Hub; (iv) the participation of Hub members in the National Council for Food and Nutritional Security (CONSEA); (v) the One Land and Two Waters Program (P1+2); (vi) the Citizenship Territories Program (PTC); (vii) the Food Acquisition from Family Farming Program (PAA); and (viii) the National School Feeding Program (PNAE). Although they do not exhaust all the public policies that were articulated by the territorial actors, we highlight the three main policy groups that marked the territorialization process in Borborema [

8,

35]:

Valuing native seeds (heirloom seeds). This was a political mobilization by entities linked to ASA-Paraíba that culminated in 2002 and led to the enactment of a state law that created community seed banks in 2002.

Federal Government Territorial Development Policies (PRONAT and PTC Programs). The Borborema Hub Territory was included (with the addition of some municipalities) in these federal programs, where governmental territorialization and territorialization as a social and political construction opened up communication channels between Borborema’s social actors and government institutions.

Policies to strengthen family farming and ensure food and nutritional security. Diversified policies for rural development focusing on smallholder farmers have had a strong impact on the Borborema network. Institutional purchases (Food Acquisition Program) and school meal purchases (National School Feeding Program) were also important. Both of these had a huge impact on the demand for family farming products, stimulating the production and consumption of healthy foods adapted to local cultures, thus fostering the market and increasing the structure of commercialization channels.

These public policies played a decisive role in strengthening the Borborema Territory at a time when the territorialization of a variety of public policies focused on family farming and territorial development. The territorialization of governance formed a positive feedback loop. However, the exceptional international conditions that made the resumption of economic growth possible in 2004 (greater international liquidity and increase in commodity prices) changed abruptly in 2008 with the unfolding of a global economic and financial crisis. Its repercussions in Brazil changed government priorities and macroeconomic fiscal policy (turning towards austerity), which impacted programs through reduction in budgets and scope. In 2016, with the impeachment (often understood by many analysts as a parliamentary coup) of President Dilma Rousseff, the Temer administration took office and swiftly implemented changes to the main regulatory frameworks (labour, budgetary, political, social security, and natural resources regulation). The administration also abolished the Ministry of Agrarian Development (MDA) and actively worked to dismantle public policies for family farming by cutting their budgets and/or implementing changes to their regulations [

48,

49].

This dismantling of public policies has had considerable repercussions in the Borborema Territory. The Brazilian state is undergoing a radical change, moving away from the position of development and a promoter and guarantor of rights and social protection as was established in the 1988 Constitution. The Brazilian government is strengthening the traditional and productivist vision of rural development with strategies that promote modernization, technological diffusion, and increased productivity [

49]. Family farms that do not “modernize” or reach high levels of productivity are served with social policies to fight poverty, disregarding and denying the environmental, cultural, social, economic, and political diversity of rural areas and of family farming as forces for development. This phenomenon has gained dramatic proportions since 2018 with the arrival of President Jair Bolsonaro to the Federal Government. Territorial development dropped off the public agenda and the Ministry’s Territorial Development Secretariat was closed.

Starting in 2016, the rapid dismantling of public policies for rural development has been an important factor of deterritorialization. The pandemic, by imposing social isolation and closing schools, has added new layers to this deterritorialization process. Along with social isolation, the public policies for the purchasing of family farming products had been paralyzed from one day to the next. Channels of dialogue with the federal government were blocked. In the Borborema Territory, we notice that the hub actors and networks were strategic in reconfiguring their strategies in view of the new political and pandemic environments. They could rapidly re-establish negotiations with municipal governments to restart commercialization channels (using digital technologies) for family agriculture and negotiate with politicians for an agenda based on agroecological family farming. In a short time period, the municipal government started buying family farming products through remote public bidding and allocated food baskets to poor students’ families during the social isolation period. Seeking more political support at the municipal level during the last election, territorial actors ran for seats on City Councils and the Mayor’s Office and negotiated commitments with other candidates to promote family farming as a territorial identity and to protect the Borborema’s territorial development project [

8,

9].

4.3. Supermarkets, New Commercialization Channels (Farmers’ Markets, Produce Shops), and the Democratization of Access to Natural Resources (Water and Seeds)

Territorial development in Borborema sought to combine the goals of social inclusion and reduction in inequalities with a concrete agroecological transition project as the basis of rural development (see Delgado, Romano, Kato [

7,

8]). Therefore, the political construction of the territory took place simultaneously with an effort to densify the territorial productive capacity by creating new niche markets and the opening of more traditional channels. During the 2000s, public policies and production support services (financing, technical assistance, commercialization, among others) strengthened the productive capacity of the territory’s farmers, which also contributed to market diversification.

According to Schmitt, “innovations in the types of markets available happen through the actions of farmers”. Prompted by debates on agroecology and the territorialization of public policies to support family agriculture, agroecological farmers’ markets already emerged in 2000 [

35]. In 2005, a regulatory institution was created, Ecoborborema (Association of Agroecological Farmers of the Borborema Compartment), which coordinates 12 agroecological farmers’ markets, which established new connections with urban populations in the territory [

9,

50]. Institutional markets have also gained prominence since the 2000s, driven by public policies that connected family production with public institutions such as hospitals and schools. As a territorial institution, Ecoborborema played a central role in the translation of these public policies to farmers and within their organization, training them to deal with bureaucratic and technical procedures. Purchases intended for school meals are noteworthy in this process [

9,

50]. In general, the circuits developed around farmers’ markets and institutional markets have ensured an increase in family income; therefore, giving them a greater degree of autonomy and greater investment capacity.

As the territory farmers’ productive capacity expanded, commercialization strategies sought to combine short commercialization circuits with longer and more traditional circuits (hybridization) [

6]. It complexified the relationships between farmers and markets. On one hand, it reinforces more traditional food systems with huge distances between production and consumption and that have higher transaction costs. These traditional systems remove any freedom that producers have over production. Schmitt calls attention to the role played by actors/equipment that link local production with different types of markets (supply centres, grocery stores, supermarkets, and hypermarkets)—the intermediaries [

35]. This can be seen in the phenomenon of selling vegetables to big farms operating in the Borborema Territory, which then resell these products to urban markets, stores, and supermarkets. Pra, Sabourin, Petersen, and Silveira, however, remind us that Borborema producers have sought to diversify their markets without becoming overly dependent on long circuits [

50]. Faced with the many uncertainties and power asymmetries, they expanded their access to traditional markets without giving up (and strengthening) the more localized short circuits [

6].

Recently, these territorial food systems faced difficulties competing with the prices and scale of large retailers (i.e., supermarkets). This was emphasized after the COVID-19 pandemic. With lockdown measures, the main channels of circulation, transportation, and commercialization of family farming products were often interrupted. This reinforced deterritorialization dynamics by altering the stages of production and distribution, food consumption, and governance mechanisms. At the same time, the health crisis closed local businesses (including farmers’ markets and other outlets) and paralyzed public institutions (such as schools, hospitals, etc.) that are important marketing channels for family farming products. During this time, large retail chains such as supermarkets and other commercial institutions continued to operate as essential services, benefiting from the increase in demand derived from the federal government’s emergency aid. All the actors that we interviewed perceived an increasing influence of supermarkets on the Borborema Territory; supermarkets arrive with pre-defined networks of suppliers and buy little from local family farms [

8,

34,

35].

In this scenario, local actors were forced to adapt and reinvent strategies that would guarantee the territorial development project or at least to soften deterritorialization forces. Progressively, the Borborema social actors managed to mobilize their capacities for action in order to re-establish their diversified commercialization channels and to reinforce territorial food systems [

8,

9]:

- (a)

Network of agroecological farmers’ markets (12 farmers’ markets). This network managed to react relatively quickly, establishing the farmers’ markets’ essentiality as a space of access to healthy food for the general population and building a hygiene protocol (separation of the stalls, availability of water and soap for sanitation, and mandatory use of masks and alcohol-based hand sanitizers).

- (b)

Network of agroecological produce shops. This is a more recent initiative, and six new fixed commercial points for agroecological food were launched where consumers can buy family farmers products in urban areas.

- (c)

Structuring delivery channels for family farming products. Following a global trend greatly accelerated by the pandemic, the actors of the Borborema territorial network have taken advantage of new communication technologies and social networks to promote their products and sales channels. Direct communication channels with customers (by internet, phone, or WhatsApp) and home delivery services have been created.

- (d)

Donation of agroecological food baskets for families (rural and urban) in situations of social vulnerability. The network was able to mobilize financial resources for the purchase of family farm food and for the composition of food baskets to be donated to families in vulnerable situations. By November 2020, 48 tonnes of food were distributed to 2100 families from seven municipalities in the Borborema Territory.

- (e)

Reestablishment of school feeding in the municipality of Remígio (negotiation of the PNAE). During the pandemic, schools had to closed, which blocked the sales channel of farmers supplying school meals. The network began discussions with the city government to guarantee public school students received school lunch kits containing food produced via family farming.

All these issues take place in a context in which other forces of deterritorialization were already in motion. It is important to stress that the consolidation of family farming also comes up against a permanent concentrated land ownership structure that characterizes the territory. According to the last IBGE Agricultural Census (2017), there were 18,464 agricultural establishments in Borborema Territory: 72% were smallholder producers, who control only 43% of the land area [

33]. This is combined with a very slow process of deruralization (decrease in the number of rural establishments and rural population) that can be related to the drought, to the advance of real estate speculation, and to the recent dismantling of public policies. For example, in recent years (2006 to 2017) in Brazil the decrease in the number of rural establishments was 2% (the same observed in Paraíba), whereas it was 5% in the Borborema Territory. The biggest decline in the number of rural establishments was observed among family farms. In 2006 they were more than 90% of establishments and in 2017 they were 72% (an almost 25% drop). Employers’ establishments, on the other hand, showed little growth. It is important to mention that changes in the way establishments were identified in the Agricultural Census methodology between 2006 to 2017 may partially explain this reduction in the number of rural establishments. Nevertheless, it does not seem to be enough to explain the magnitude of the reduction in the participation of family farming and the large growth of employer establishments. This issue must be further investigated in future field research studies.

The results must be analysed in the light of territorial occupation. In terms of relative occupied area, family producers’ establishments increased their share (from 46% to 48%), while employer establishments dropped from 54% to 52% [

36]. From 2006 to 2017, in terms of relative area, family farming establishments increased their participation in total from 46% in 2006 to 48% in 2017 (

Figure 2). The decrease in employer’s establishment was greater (to 54% to 52%). We conclude that, despite the drop in establishments, family farming in Borborema Territory remains resilient and increased its relative share in land area. Borborema Territory is formed mainly by smallholding farms with small areas: 75% of agricultural establishments had an area less than 5 hectares, compared to the Brazilian average of 37%, and 20% of agricultural establishments had an area of 5 to 20 hectares [

36]. It reveals a more or less permanent picture of small-scale establishments, since 95% of them have less than 20 hectares. According to Brazilian law, the area of establishments considered to be family farming in the Borborema Territory vary (depending on the municipality) from 48 to 120 hectares (i.e., establishments with areas of up to four fiscal modules—módulos fiscais in Portuguese). In 2017, among family farming establishments in the Borborema Territory, those that suffered the greatest reductions were those with dimensions smaller than 0.5 hectares (an average decrease of 26%) [

36]. They probably also correspond to the most vulnerable establishments: the poorest and least organized (most of the times they remain “invisible” to State and social movements), with worse access to land and natural resources, with weak connections with the market, and with low capitalization. The decrease may be related to poverty and drought, to difficult access to land (i.e., absence of property titles), to leaving rural areas, and to the abandonment of rural and agricultural production. A more detailed and accurate investigation should be carried out in future research studies to understand this emerging trend.

On the other hand, the maintenance and consolidation of family farming production systems (expanding its relative share in the total area of the territory) can be attributed to the numerous territory-originated social innovations, such as the use of cisterns, the resumption of heirloom seeds, the development of diversified productive systems, and multiple commercialization channels. All of them have enabled greater and improved coexistence in the semiarid region of Brazil by increasing family farmers’ resilience and their production capacity during periods of drought. Concerning water sources in Borborema Territory in recent years, the access to water for consumption and production was expanded. As we can see in

Figure 3, rivers, lakes, streams, and springs have lost their share as available sources of water, dropping as the source for 44% of establishments in 2006 to 21% in 2017. At the same time, cisterns and wells, which had been a source of water for 55% of establishments, reached 79% in 2017 [

36]. In times of drought (from 2012 to 2016 Borborema Territory faced a severe drought affecting rivers and water reservoirs) and increased climate change, the creation and multiplication of plate cisterns for water storage (rain) was an important initiative to ensure families’ access to water for consumption and production. These innovations were central in promoting the resilience of local family farming and in the construction of new rural development strategies.

Another important social innovation has been the resumption of the use of heirloom seeds and the strengthening of community seed banks that allow for the conservation of genetic material that is better adapted to specific territorial characteristics. This increased the resilience of production systems (by making them better adapted to the local climate and soils) and expanded the productive capacity of family farmers, which in turn is linked to their ability to diversify and expand their marketing and distribution channels.

We highlight three strategic dimensions of community seed banks [

33,

35]:

They operate as safety stocks to overcome adversity, even making it possible to use them as food (or as a production factor);

They encourage farmer organization, thus enabling improvement in management capacities, the transition to agroecological agriculture, and the expansion of the communities’ capacities;

They stimulate the resumption of local seed diversity (heirloom seeds), which are well adapted to the local climate and whose diversity reduces production risks. In the state of Paraíba, “Seeds of passion” is the name given to native seeds that are preserved by generations of farming families as a way to conserve genetic material that is adapted to the local management and production methods of these peasant families.

Currently in the Borborema Territory, rural areas and family food producers remain common: in 2020, the territory’s population density was 113.3 inhabitants per km

2 (by comparison the OECD considers municipalities with densities of up to 150 inhab/km

2 as rural). About 42% of the population was still living in rural areas, and family farming producers account for 71% of total agricultural establishments [

36]. The existence of a culture of participation in the Borborema Territory, the strengthening of different territorial markets, the mobilization around family farming, and a territorial identity may be considered as active forces that allow for the maintenance of the territorial project even in a context in which the forces of deterritorialization have become more present; therefore, the territorial project is increasing its resilience. This seems to be the case for the territory investigated in this paper.

5. Discussion and Final Remarks

For some time now, we have been facing a systemic capitalist crisis that can be felt in the economic, social, environmental, and political fields. The COVID-19 pandemic and social isolation measures emphasised this scenario of increasing inequalities and posed new challenges to rural development. There are many signs of the changes: the current economic recession that has affected almost all countries; the urgency needed to face social inequalities; the struggle against hunger and extreme poverty; the loss of biodiversity; the fight against new epidemics; and the negative effects of climate change. Many analysts point out that the solution is in creating a more just and sustainable world that will necessarily involve the transformation of the way we produce, distribute, and consume food. This would require a system that reconnects production and consumption by returning to more territorialized food systems [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Based on many different sources (literature review, secondary data, and online interviews with individuals and focus groups), this paper seeks to reflect upon a few aspects of the territorial development paradigm in Latin America in the first two decades of the 2000s. This was considered some specialists to be the “first generation” of territorial development policies [

24]. Our hypothesis is that territorial capacities obtained from a trajectory of territorial development increase territories’ resilience to crisis and favours the consolidation of territorialized food systems. Territorial capabilities increase due to: (1) the previous existence of shared experiences and territorial networks that favour social innovation and stimulate the creation of more territorialized production systems; (2) the previous accumulation of public policies at different levels that empower local social actors and promote more inclusive and sustainable productions patterns; and (3) the capacity of territorial actors to assume a leading role in development policies.

The recent Latin American experience demonstrates that, in order to deepen reflections on territorial development, we need to face the complexity that permeates the different perspectives and actions that unfold in a territory. A territory results from different initiatives implemented by social actors that carry different interests, logics, objectives, and capabilities. Thus, “territorial development” will be decisively marked by the ways in which people and organizations interpret and appropriate land (nature); how they structure production (and establish flows between with external areas); and how they occupy space, through multiple processes that signify and re-signify territorial identities.

This shows us the methodological importance of recognizing the often subtle existence of multiple territorialization and deterritorialization forces that coexist simultaneously in many territories. This framework avoids the potentially more attractive, but misguided, analyses of territorial development. Local development must be seen as a dialectical process in which territorialization and deterritorialization dynamics are always present. We identify a few ongoing processes of simultaneous territorialization and deterritorialization in Borborema Territory. Our approach to territorialization prioritized the construction and strengthening of the territory (or territories)—in its functional (resources) and symbolic (identities) dimensions—by the social actors who actually live there, particularly family farmers and their organizations (such as unions, associations, networks, and markets). In our study, the territorialization forces contribute to an alternative model of agricultural and rural development that is based on family farming and territorial food markets. They resulted from several initiatives, including the consolidation of dense social territorial networks, protection of heirloom seeds, construction of cisterns to store water, the strengthening of a huge channel of communication with rural and urban areas, and a closer dialogue with federal and local governments. These initiatives not only provided local actors with better instruments and capabilities to act in a crisis (agency), but also made it possible to open new channels for marketing family farming products, especially (but not only) during the pandemic. The deterritorialization processes, in turn, refer to the economic, demographic, climatic, technological, political, and social processes that undermine this territorial political project and erode the bases and possibilities of an alternative model of life–production–consumption. We have included here the advance of supermarkets, the huge concentration of territorial agrarian structure, the slow deruralization process, and the dismantling of rural development public policies.

In our perspective, the strengthening of the territory’s social (and political) fabric appears as a key element for territorial development. Territorialization dynamics converge to and are reinforced by a certain “vision for the future” for the territory shared by territorial actors. Our case study shows that fertile ground emerges when this project is fuelled by the territorialization of governance, the territorialization and articulation of public policies, and by the social construction of alternative and more localized markets that strengthen their productive and organizational capacities. At the same time, these processes contribute to consolidating the short circuits of production and consumption, thus creating a virtuous circle.