1. Introduction

As climate change is the pervasive topic in today’s world, it is essential to explore and recognize the largest contributors to climate change. Plastic products are found to be a huge contributing factor to climate change in different ways. The fossil fuel industry is ranked as the third-largest source of carbon emissions, and it is informally linked to the growing plastic industry [

1]. According to the study conducted by the authors of [

2], producing a kilogram of the plastic product takes 185 L of water, and the production of these plastics is highly dependent on fossil feedstock (mainly natural gas and oil). It requires up to 6% of current global oil production to produce plastic products, and this is expected to increase to 20% by 2050 [

3]. People started using plastic products to carry groceries and goods by hand in the 1950s, and these products quickly gained popularity over the last quarter of the twentieth century [

4]. These plastic products have more than doubled between 1950 and 2015, with an annual output of 322 million metric tons (Mt) every year, which is expected to double by 2035, and nearly quadruple by 2050 [

5].

Plastic bags are inexpensive products to manufacture; however, the low price does not account for the environmental costs of using plastic bags. For many years, plastic has been one of the most essential tools used to generate the materials of the physical world. These plastic items are dumped into the ground after usage, preventing the soil from producing nutrients. As a result, soil fertility is reduced, which has an impact on the agricultural outputs. Furthermore, from an economic point of view, improper plastic waste management decreases revenue generated from tourism, due to unsightly plastic products thrown everywhere. Moreover, the study conducted by the authors of [

6] suggests that the domestic washing of textiles and garments is a constant and widespread source of plastic microfiber emissions into the environment.

For all their benefits, though, plastics also present challenges. In 2017, the United Nations declared plastic pollution a worldwide crisis [

7]. The announcement caused several establishments to adjust their corporate strategies and start preparing for an accelerated transition to a circular economy. In recent years, technological improvements, societal changes, institutional amendments, and eliminating single-use plastics are viewed as positive changes toward reducing the impact of plastic products. However, the inadequacies and inefficiency of current plastic waste management will create another environmental crisis [

8]. Furthermore, COVID-19 outbreaks take the complexities of plastic waste management to a challenging level. The way of life for individuals is becoming dependent on personal protective equipment, which increases the demand for plastic products [

7].

The mitigation of plastic production is indicated to reduce the use of plastics as much as possible. However, the way to reduce the usage of these plastics is unclear. According to the authors of [

9], Plastic bag waste is a major challenge in several countries across the world, especially in Africa, and governments have adopted various approaches for plastic bag waste management that include levies, bans, and/or the combination of the two to reduce the impact. On the other hand, some scholars argue that reducing the usage of plastic products can be done by providing training and awareness to the uneducated sector of consumers without banning and taxing [

5]. Many arguments suggest consumers are obligated to be aware of the causes and impacts of plastic production through cost burden [

6]. According to the research in [

10], the selection of policies among countries is specific and comes down to the source of pollution, the country’s institutional characteristics and infrastructure, consumer preferences, habitual behavior, and the economy’s overall sectoral composition.

It is believed that significant societal change is required to achieve climate neutrality across the world; therefore, plastic tax, as part of green taxation, must be part of a larger policy framework that incorporates several measures, including price mechanisms, subsidies, standards, and public infrastructure investment [

11]. A plastic tax is conceptually similar to a carbon tax, which imposes a carbon tax to punish utilities that produce the most emissions. These taxes target an externality, as economists call it: catastrophic climate change in the case of a carbon tax and runaway pollution in the case of a plastic tax. The impact of a plastic tax on consumers could raise the price of plastic products, thereby discouraging their use [

12]. Besides, having a plastic tax could benefit society by establishing a price for social costs and incentivizing behavioral changes by businesses and individuals [

13]. This action can help to mitigate plastic waste management and environmental crisis.

More specifically, at the country level, most developed and developing economies uses the strategy of taxing plastic products (see

Table 1), whereas the majority of poor and developing economies have chosen to ban plastic products from the market, rather than to tax them. However, the study conducted by the authors of [

14] suggested that blanket bans are not the best policy for developing and poor countries to reduce the effect of plastic products. Instead of turning to fees, creating consumer awareness and conducting campaign plans are better approaches to mitigate the effect. To this end, the study conducted by the authors of [

4] suggests that taxing plastic products is a non-alternative method for the poor and developing countries, as they can generate more revenue from this taxation.

In this context, the circular economy is found as an alternative to the current linear structure, as it is more related to making, using, and disposing of the economic model [

11], keeping resources in use for as long as possible, extracting the most value from them while in use [

12]. A circular economy provides an opportunity to reduce the negative effects of plastics while maximizing the advantages of plastics and their products, resulting in environmental, economic, and societal benefits [

13]. Particularly, the plastic tax has found an important basis for reducing the effect of plastic products, since it is a tax on environmentally harmful products [

14]. On the other hand, the study conducted by the authors of [

9] shows that banning plastic products is the best policy for those countries that cannot operate under a circular economy. However, the findings of the study further imply that several countries are struggling to reduce the harmful consequences of plastic bags, even after banning them, due to a lack of policy effectiveness.

This could raise the question among scholars as to why most countries choose to ban plastic bags rather than to convert to taxing them, as most developed countries do. This study will attempt to answer the above-raised question by systematically reviewing previously published studies on this specific study area. From the above discussions, the study identified taxing or banning as the main solutions for reducing the impact of plastic products. Various countries adopted different strategies based on their capacity to implement the policy, as well as their ability to identify the opportunities and challenges. The inconsistent findings of previously conducted studies motivated the authors to conduct the current study. More specifically, the policies adopted by a majority of African countries (banning plastic products, rather than taxing them), which is a reversal of the policies used by the majority of developed economies, is also another reason that motivates the authors to investigate the potential opportunities and challenges of plastic products. The study will contribute to the existing literature by summarizing the challenges and opportunities of plastic products using selected policies, and by providing future research direction for the study area. As the result, the main purpose of this study is to review the potential benefits and challenges of plastic products under the umbrella of taxing or banning plastic products. In line with reviewed papers, the study is also interested to investigating the current policies of different countries regarding plastic products. This could provide information to the readers regarding the number of counties currently banning plastic products from the market, as well as those dealing with them by minimizing their usage through taxation.

Table 1 of the study shows the policies used by different countries across the world to manage the problem of plastic products.

Table 1 shows the type of policy implemented by each country, along with the respective year. Based on data availability, the study tries to investigate the policies adopted for plastic products. As it can be seen, the number of those countries that adopted taxing as an alternative policy is 24, whereas the number of countries with a banning policy is 27. These numbers may be close; however, the number of countries that implemented banning is greater. The policy of banning plastic product is frequently adopted in African countries, whereas the policy of taxing of plastic product is more widely adopted in Europe. Based on our data, Germany was the first country to impose a tax on plastic products in 1991, and this trend quickly spread, with Denmark imposing a tax on plastic bag products in 1994. On the hand, Bangladesh was the first country to ban plastic items from the market.

Figure 1 of the study shows the annual production of plastic products worldwide from 1950 to 2020 (in million metric tons). The data extracted from the World Bank implies that the number of plastic products produced annually is increasing over time. Despite growing concerns about the environmental consequences of both plastic production and waste, recent estimates show that plastic production and waste will more than double by 2035 [

15]. Hence, internationally coordinated action from a variety of stakeholders is required.

4. Results

Concerning the debate over plastic products, in this study, discourse analysis was used based on two separate storylines. The actors for both storylines are given special treatment to recognize both the opportunities and challenges of both storylines. The first storyline recognizes plastic bag taxes as an opportunity for sustainable development (S1), while storyline 2 recognizes banning plastic products from the market as an opportunity for sustainable development (S2). Previously conducted studies used the actors in both storylines.

Figure 4 shows the content details of storylines 1 and 2, followed by a discussion from previously published studies.

The processes of the formation of the first and second storyline are depicted in

Figure 4 of this study. Actors, in particular, express ideas about the benefits and challenges of taxing or banning plastic products. The first storyline’s legitimacy is based on the potential capacity of a plastic tax to promote sustainable development and environmental protection. Different authors support this storyline. The study conducted by the authors of [

8] implies that the tax on plastic products is a key factor in transferring the household’s attitudes towards material recycling. Furthermore, the study conducted in [

10] suggests that the overall beneficial impact of environmental taxes on items such as plastic bags results in reduced use, as well as a corresponding low cost of implementation. The study argues that taxing plastic products is the best policy to reduce its impact, as well as to generate revenue. The study conducted by the authors of [

22] presented another finding which supports the taxing of plastic products. The study was conducted to show the empirical evidence regarding the ability of incineration taxes to change current waste management practices, as well to provide policymakers with insights into the effectiveness of an incineration tax. The findings imply that the decrease in the incineration tax did not change waste management practices. Different studies provide different outcomes regarding the benefits of having a tax on plastic products. Some argue that it could help in the generation of revenue for the government [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Taxing plastic products is viewed as a source of revenue for the economy, particularly in poor and developing countries [

27,

28,

29]. The revenue generated by taxing plastic products is used to fund various government projects, while also indirectly creating job opportunities for the unemployed [

30]. It is also believed that properly managed plastic waste creates employment opportunities for the unemployed segments of the societies [

31]. Discarded plastic products can be collected and recycled. In this case, the collection of these plastic products from various waste areas provides employment opportunities for some low-income individuals.

Introducing a plastic tax is helpful for influencing both the manufacturer and the consumer. Taxed plastic products increase the price of plastic per user, and people are motivated to consume less plastic. People are generally found to be loss-averse and do not want to pay for something that was previously “free,” or “cheap.” For that reason, they often perceive a tax in a negative light, and tend to avoid it [

32]. Furthermore, decreasing customer demand leads the manufacturing companies to look for other options and indirectly decreases the output level of plastic products [

33]. To this end, a tax on plastic could further push manufacturers, scientists, and academic researchers to focus on more research and development regarding innovations to improve the efficiency of plastics [

34,

35].

Plastic products are used as raw materials in industrial and construction processing. Since they are used to produce plastic oil, they are used to lubricate industrial machines and generate oil that can be exported to foreign markets, prompting foreign exchange and saving millions of dollars in foreign currency that could have been used to import machine oil [

36,

37,

38]. In this case, the benefit is greater for countries where agricultural activities account for the majority of their economy. It is also argued that plastic waste contributes significantly to energy recovery because energy recovered from plastic waste can contribute significantly to energy production [

36]. As a result, the contribution of energy products obtained can be used to supplement the country’s current shortfalls in energy supply. To this end, imposing a tax on plastic products increases their price, and plastic materials are considered valuable by users; thus, they are usually sorted out for reuse. As a result, the materials are reused several times before they lose their utility value and are discarded [

37].

Global experience implies that there could be a greater economic benefit from taxing plastic products. The study conducted in [

38] implies that several countries, including England, Ireland, the Netherlands, China, the Philippines, and Australia, have demonstrated that a plastic bag fee is effective in reducing the use of plastic bags [

39]. More specifically, according to the authors of [

40], China introduced a plastic product tax, with a bag fee of CNY 0.20–0.50 in 2008. After the tax implementation, it was observed that the total plastic product consumption declined by 64%. Furthermore, the study conducted by [

41] argues that, in England, after the introduction of a plastic bag fee of GBP 5 on major businesses in 2015, there was a 36% decrease in plastic product consumption.

According to the research presented in [

35], Portugal introduced a plastic bag tax of EUR 0.10 on plastic bags in 2015, and following the introduction, there was a 74% reduction in plastic bag usage observed, and reusable plastic products increased by 64% after the introduction of the plastic tax. Furthermore, Wales introduced a single-use plastic bag fee of GBP 5 (USD 0.07) in 2011 [

42]. Following the introduction of the plastic tax, a 70% reduction in consumption was observed. Hence, it can be observed that the global experience shows that the plastic product tax has shown a significant reduction in plastic bag consumption [

38]. Plastic is also used in making vehicles lighter, and therefore more fuel-efficient. Plastic food wrapping prolongs food shelf-life and reduces excess food waste [

43].

At the same time, the study discussed the opportunities for banning plastic products. Scholars argue that banning plastic products has an indirect contribution to economic growth. One pioneering study that supports the banning of plastic products is the study conducted by the authors of [

30], which suggests that unmanaged plastic waste management can reduce the overall economic activities of a country by reducing its level of tourism. This suggestion is further extended and supported by the study in [

44]. The plastic ban creates a cleaner environment, since there is no more plastic thrown onto the street. This is indirectly helpful in attracting tourism. Furthermore, the study conducted by the authors of [

45] highlights that banning plastic products creates a new way of making environmentally friendly shopping bags. It argued that the plastic ban is expected to improve marine life and drainage infrastructure, while reducing the dependence of non-human activities on petroleum [

46]. Hence, banning plastic products from the market could contribute to solving environmental issues, such as global warming and ocean acidification, as well as to the improvement the agricultural sector because these plastic products are serious problems for these previously mentioned activities.

The second part of the first storyline dealt with the challenges of imposing a tax on plastic products. In this regard, previous studies highlighted some challenges that are more specific to taxing plastic products [

47]. As it can be seen in the above

Figure 5 of the study, the identified challenges are a lack of proper collection systems, separation at the source of disposal, a properly designed operating system, clear policies and sanitation rules, organizational capacity, unreliable collection services, and a willingness to pay.

Lack of sorting the waste is also another challenge, as is supported by the study conducted by the authors of [

48], who indicated that solid waste created in houses is discarded at transfer stations along with other plastic products, indicating that there is no tendency to sort organic waste at the household level. The study further suggests that organic materials come from rural areas, depleting nutrients from rural soil to feed the urban population; leftovers after consumption have no way of returning to the source to build the soil; instead, they are lost and cause problems for human health and the environment in different cities due to poor waste management. The study conducted by the authors of [

49] implies that the challenges of most plastic products are related to the collecting system. Another issue regarding the collection of plastic waste is the number of containers in open area [

45]. In this case, there must be sufficient containers to collect waste generated by households; otherwise, individuals will be forced to throw their garbage into an open area. If the proper plastic waste management is unimplemented, taxing plastic products does not solve any environmental issues while providing economic benefits. However, it is argued that the implementation of the tax forces users to seek other alternatives because the tax raises the price of plastic products, causing an unwillingness to pay that results a decrease in overall consumption.

The legitimacy of the second storyline (S2) is based on the potential ability to ban plastic products from the market to promote sustainable development and environmental protection [

46,

47,

48,

49]. Short-termism in unemployment was found to be the main disadvantage of banning plastic products. In this case, in the countries where the level of the manufacturing sector is much lower than the level of the agricultural sector, the substitution of plastic products will be difficult if plastics are banned [

50,

51,

52].

More specifically, these bags are more detrimental to agricultural production because some crops cannot grow in areas where plastic bags have settled. Many countries around the world, particularly in Africa and Asia, are opting for a ban, rather than a tax, on plastic bags [

53]. As evidence, in early 200, among Bangladeshi plastic bag users, between 85 and 90% of plastic bags in Dhaka were discarded on city streets after use. As a result, the Bangladeshi government prohibited the use of plastic bags in 2002 [

54]. Furthermore, the experience gained from Rwanda shows that, after prohibiting the use of plastic products in 2008, the country became the cleanest city in the world [

39].

In 2016, the Israeli government implemented a hybrid ban and levy strategy, prohibiting supermarkets from distributing plastic bags less than 20 microns thick and requiring them to charge for the use of thicker plastic bags. As a result, in the following year, plastic bag usage decreased by 80%. Furthermore, Botswana, South Africa, Mozambique, and China have initially combined the ban and levy approaches into a single strategy. These countries prohibit the use of plastic bags with less than a certain wall thickness and require retailers to charge a fee for thicker plastic bags [

39].

Both storylines imply that plastic products have a significant environmental impact, as well as an economic benefit. Supporters of storyline 1 (S1) argue that taxation is more appropriate for poor and developing countries, where the majority of legal frameworks governing plastic products are ineffective. However, the result of empirical studies conducted on the practical application of plastic legislation shows reverse efficiency.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Reviewed Papers

The review was shaped by gathering resources from the various databases chosen for this study. After all criteria were met, 42 studies were used for the final discussion. As shown in

Figure 6, the majority of the resources used in this study were articles from journals, accounting for 90% of the total. Conference paper contributed 5% of the total review study. The remaining 5% of the study was comprised of book sections and books, respectively.

4.2. Yearly Distribution of Materials Used

Among the resources used for this study,

Figure 7 shows the yearly distribution of published articles used in this study and confirms a consistent increase in the publication of studies regarding plastic product issues, indicating that the research area is receiving increased scholarly attention, as evidenced by the consistent increase in publications. According to the study findings, there has been a significant increase in the number of publications from 2017, with two papers, to 2019, with 19 papers, indicating that plastic products are still at the heart of current research areas involving finance, economics, and environmental studies.

4.3. Methodological Characteristics of Reviewed Studies on Plastic Products

This study also highlights the methodological aspects of the reviewed studies, which differ in terms of data collection and analysis methods. The study’s findings show that there were many different methodological research designs used in conducting plastic product research over time. For example, with a 38% contribution, the econometric analysis was used in the majority of the studies used in this review. Moreover, comparative analysis, econometric analysis, trend analysis, qualitative analysis, cluster analysis, correlation analysis, systematic analysis, status analysis, and hybrid analysis were the types of data analyses used in previously conducted studies. The following (

Table 2) shows the details of the methodological characteristics used in previous studies.

5. Discussion

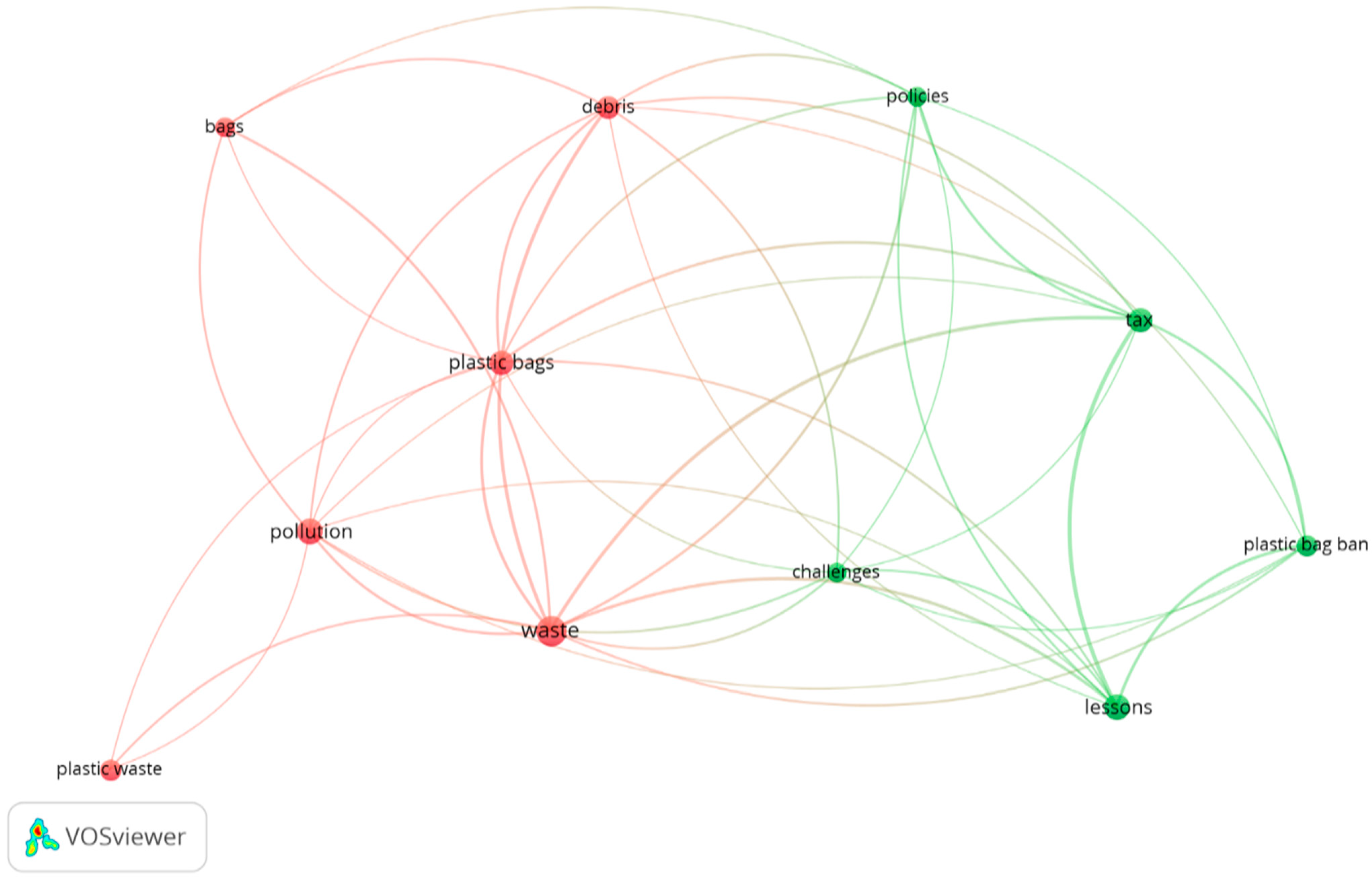

This study systematically reviews the challenges and opportunities of plastic products under two different policies (banning and taxing). The fast scanning of the study result implies that global academic interest in plastic products is increasing over time. The methodological approach used in the reviewed papers varied based on their objectives, and the approach chose was found to be a benchmark for those scholars interested in conducting a new study on the specific area of plastic products. The results of keyword analysis indicate the areas in which academic writers are interested in investigating, namely the current policies and procedures, legal frameworks, taxing, banning, and waste management of plastic products. Furthermore, the review results of previously conducted studies imply that there are factors that influence policy choices among countries. Those factors are classified as global and national problem pressure, global public pressure, and national lobby groups, as well as political and technical feasibilities. The results also showed that the degree of influence varies between countries.

More specifically, the study looked at how different countries implemented policies to reduce the impact of plastic products, such as by banning or taxing them. The findings show that the majority of developed economies have implemented a policy of taxing plastic products, whereas the majority of developing countries have implemented a policy of banning them. It was discovered that in 1991, Germany was the first country to impose a tax on plastic products, and this idea quickly spread, with Denmark imposing a tax on plastic bag products in 1994. Even though Germany and Denmark were the first countries to impose plastic bag taxes in 1991 and 1994, the previously conducted study [

55] indicates that only Denmark can be regarded as a plastic bag policy pioneer. It stated that in Germany, the tax imposed was on all packaging materials that were considered waste, specifically plastic bags. On the hand, Bangladesh was the first country to ban plastic items from the market [

56]. The decision was made after the majority of plastic bags in the country (between 85 and 90%) were thrown in the streets after use. As a result, in 2002, the Bangladeshi government outlawed the use of plastic bags.

Both policies have advantages and disadvantages; however, the selection primarily depends on the countries’ ability to manage the chosen policies. A plastic product ban is frequently observed in African countries [

57]. The reasoning behind this is that taxing keeps plastic products on the market, which necessitates proper management of disposals made by each household. This management entails preparing disposal containers in every corner of the city, developing proper collection systems, separating the disposal source, creating a properly designed operating system, instituting responsible policies and sanitation rules, assuring organizational capacity, and initiating reliable collection services. The study conducted by the authors of [

9] supports the above argument by providing evidence that African countries are hindering effective plastic bag waste management because of poorly enforced plastic bag legislation, resistance from stakeholders, and limited effective substitutes. Besides, every household’s awareness plays a big role in implementing these management tools. However, in the context of Africa, where the level of educational outreach is low compared to that in developed countries [

9], it is difficult to tax plastic products using those highlighted management mechanisms, since using and discarding plastics on the street is becoming a tradition [

34].

On the other hand, it argued that the tax on plastic products would allow the continued production of single-use plastics, generating revenue to subsidize the recycling industry [

31]. This revenue would be used to fund recycling and composting infrastructure, which would help to boost overall economic growth. In theory, it was thought that instituting tax policies on plastic products would render recycled materials more competitive, making it economically viable for a product manufacturer to use recycled products [

35].

A plastic tax is conceptually similar to a carbon tax, in which a tax is imposed to punish utilities that produce the most emissions. Ideally, this has two advantages. First, it incentivizes polluters to reduce carbon emissions by switching to renewable energy sources. Second, the tax revenue is used to fund green energy projects, or is returned to residents as a dividend. These taxes target an externality, as economists call it: catastrophic climate change, in the case of a carbon tax, and runaway pollution, in the case of a plastic tax. The impact of a plastic tax on consumers could raise the price of plastic products, thereby discouraging their use.

Finally, under the premise of banning and taxing, this study summarized the following points as the potential benefits and challenges of plastic products. In doing so, the narratives were constructed using discourse analysis, and investigations were conducted based on the developed storylines.

The study summarized that having a tax on plastic products could provide more opportunities for the countries that are effective in applying plastic legislation, and create a great challenge for those countries with poorly enforced plastic bag legislation. Taxing plastic products will benefit the generation of revenue, employment, industrial processes, construction processes, and recycling. However, a lack of proper collection systems, separation at the source of disposal, a properly designed operating system, clear sanitation rules, organizational capacity, reliable collection services, and a willingness to pay were found to be existing challenges of taxing plastic products, as a tax keeps the plastics on the market.

Furthermore, all stakeholders must develop an awareness of the usage of plastic products. Plastic manufacturers, as well as firms and individuals who import plastic bags for sale, must create consumer awareness and campaigns to implement more changes regarding plastic bag operations. Governments and policymakers play a critical role in developing the necessary legislative framework to encourage mitigation actions that contribute to the reduction in plastic waste at the source, as well as encouraging the cleanup of plastic pollution on coastlines.

More specifically, community-based associations have found it necessary to overcome this issue. Private businesses, of course, have had to rethink their business models to shift their focus to recycling or bag manufacturing. Those countries which adopted the banning policy should question themselves, since taxing plastic products using the proper management of plastic legislation will generate many economic benefits to that country. This study suggests that future research be conducted regarding which policy will benefit specific countries, from an environmental and economic point of view, by making comparative analyses among different countries that adopt different policies within the same continent. The study also suggests that future studies be conducted on why banning diffusion is so high in Africa. In addition, it is important to investigate how African policymakers respond to this issue.