Sustainable Community Transformation and Community Integration of Agricultural Transfer Population—A Case Study from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Community Integration of the ATP

2.2. Community Identity of the ATP

2.3. Community Participation of the ATP

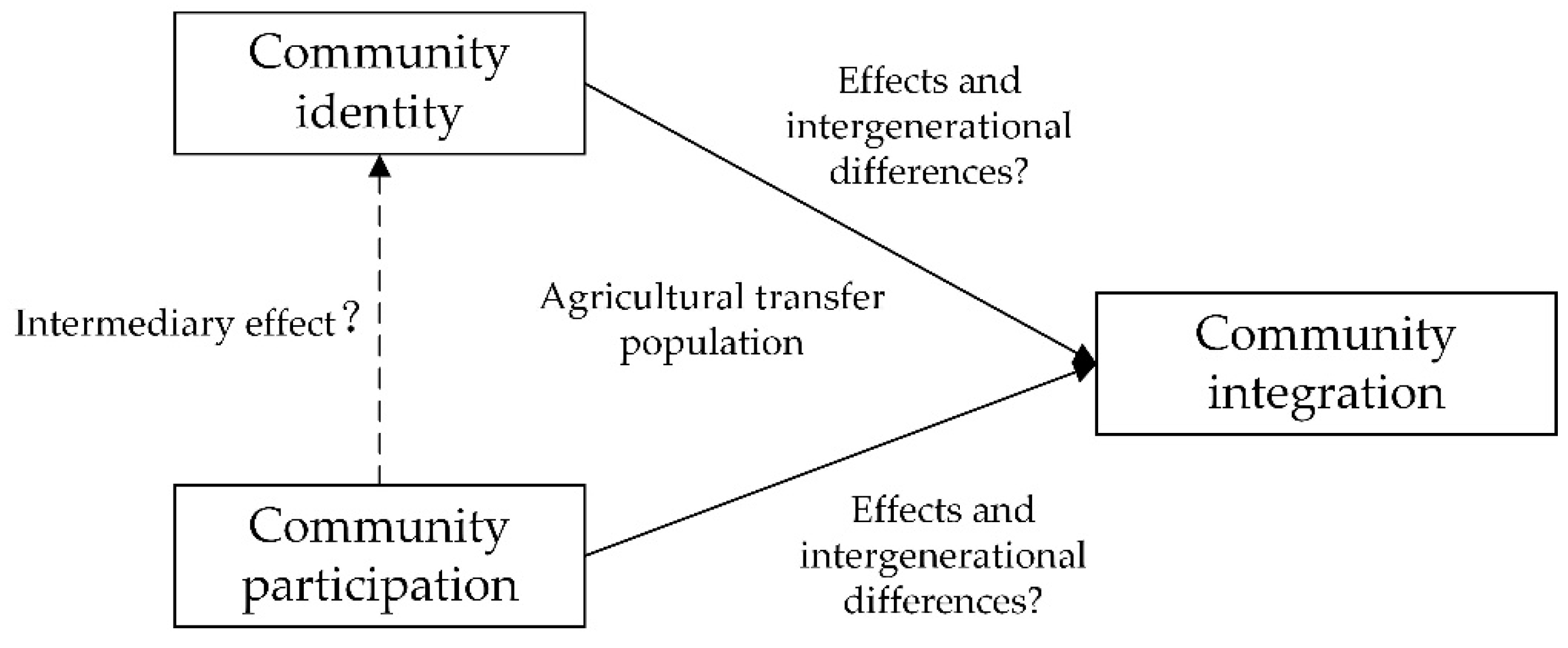

3. Theoretical Analysis

3.1. Social Support Theory

3.2. Push-Pull Theory

3.3. Social Identity Theory

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Source

4.2. Variable Selection

4.2.1. Dependent Variable: Community Integration

4.2.2. Independent Variables: Community Participation and Community Identity

- (1)

- Community identity

- (2)

- Community participation

4.2.3. Other Control Variables

4.3. Model Construction

4.3.1. Ordered Probit Model

4.3.2. Test for Mediating Effects

5. Results

5.1. Influencing Factors and Intergenerational Differences in Community Integration

5.2. Model Robustness Tests

5.2.1. The Regression Result of Changing the Dependent Variable to “Household Relocation Willingness”

5.2.2. Replace the Regression Method with Ordered Logit Regression Results

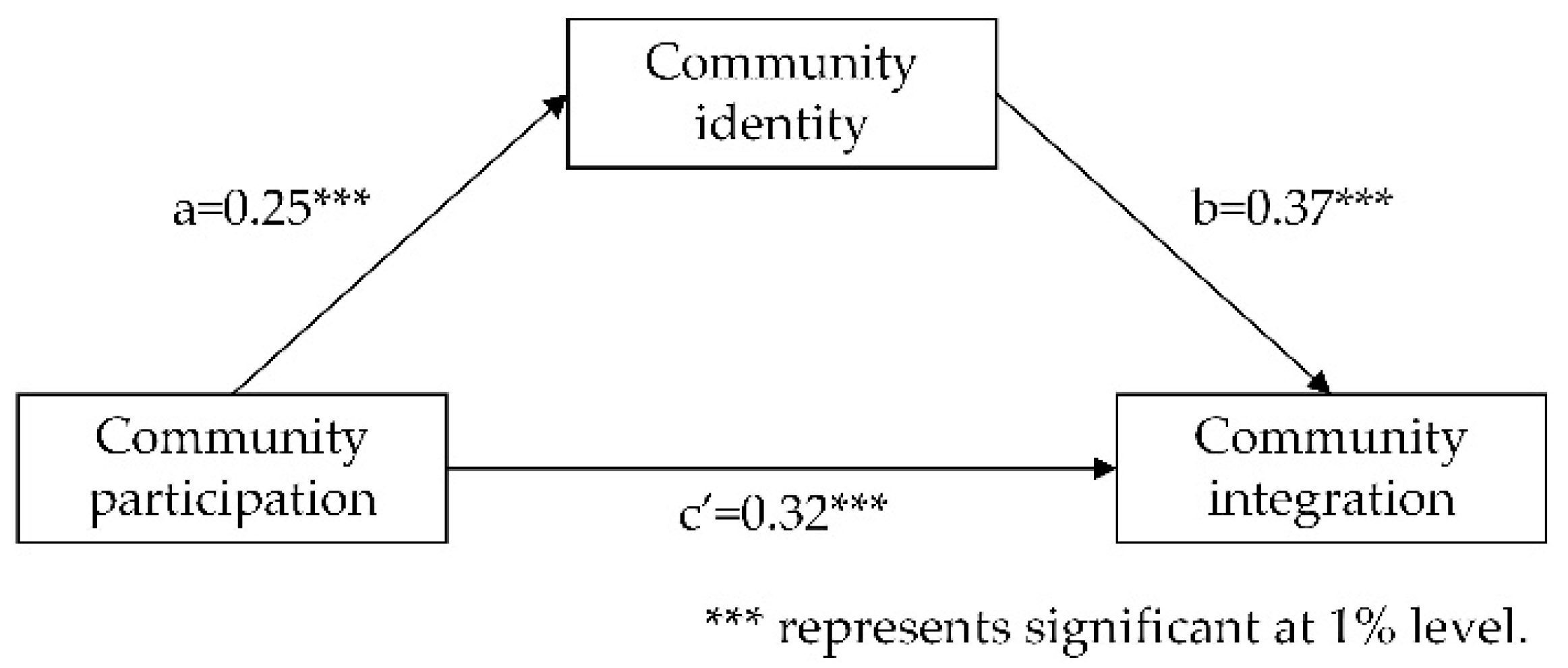

5.2.3. The Mediating Effect of Community Identity between Community Participation and Community Integration

5.2.4. Survey on Willingness to Integrate and Reasons for Staying

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Recommendations

- (1)

- Equalize the supply of public services for the ATP.

- (2)

- Improve the community governance system with community autonomy as the mainstay.

- (3)

- Promoting ATP citizenship with community integration.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, L.B.; Friedland, W.H.; Nelkin, D. Migrant Agricultural Workers in America’s Northeast. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1972, 25, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOM; ILO. Risks and Rewards: Outcomes of Labour Migration in South-East Asia; IOM: Grand-Saconnex, Switzerland; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Patrinos Harry, A.; Emmanuel, S.; Trin, L. Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Economic Opportunities and Social Networks; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; LeGates, R.; Fang, C. From Coordinated to Integrated Urban and Rural Development in China’s Megacity Regions. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardiansjah, F.H.; Sugiri, A.; Sari, G.P. Urban Population Growth and Their Implication to Agricultural Land in the Process of Metropolitanization: The Case of Kabupaten Sukoharjo, in Metropolitan Surakarta. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 328, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Long, H.; Liao, L.; Tu, S.; Li, T. Land Use Transitions and Urban-Rural Integrated Development: Theoretical Framework and China’s Evidence. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Yan, X. The Formation and Evolution of “Urban Villages”, Informal Immigrant Settlements in Economically Developed Areas of China—The Case of Cities in the Pearl River Delta. Manage World 2005, 8, 48–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G. An Analysis of Urban Renewal Decision-Making in China from the Perspective of Transaction Costs Theory: The Case of Chongqing. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020, 35, 1177–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanders, R.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Y. Marginalisation in the Chinese Countryside: The Question of Rural Poverty. In Marginalisation in China; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, D.B. Periurbanization and the Politics of Development-as-City-Building in China. Cities 2016, 53, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapally, T.R. The SMART Framework: Integration of Citizen Science, Community-Based Participatory Research, and Systems Science for Population Health Science in the Digital Age. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branker, R.R. Labour Market Discrimination: The Lived Experiences of English-Speaking Caribbean Immigrants in Toronto. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2017, 18, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meeteren, M.; Mascini, P.; van den Berg, D. Trajectories of Economic Integration of Amnestied Immigrants in Rotterdam. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2015, 41, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fix, M.; Zimmermann, W.; Passel, J.S. The Intergration of Immigrant Families in the United States; Urban Inst.: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, R.; Ran, G. How Do Two Generations of Migrant Workers Differ in Their Sense of Community Equity?—A Study of Migrant Workers’ Experiences in the Context of Their Integration into Urban Communities. J. Public Adm. 2017, 1, 89–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Y.; Ke, H. An Analysis of the Citizenship of Migrant Workers Based on the Perspective of Community Integration. Rural Econ. 2014, 8, 105–109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Teng, F. Five Prospects of New Urbanization—A Case Study of Suqian City, Jiangsu Province. In China’s Reform and New Urbanization; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirun, T.; SooHooiSin, J.; Wei, C.C. The Role of Job Embeddedness in “New Generation of Rural Migrant Workers” Turnover Intention in China. J. Bus. Soc. Rev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 4, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, C.L. Conspicuous Consumption in Emerging Market: The Case of Chinese Migrant Workers. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T. Rights in Action: The Impact of Chinese Migrant Workers’ Resistances on Citizenship Rights. J. Chin. Political Sci. 2014, 19, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boheim, R.; Christl, M. Mismatch Unemployment in Austria: The Role of Regional Labour Markets for Skills. SSRN Electron. J. 2022, 9, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.R. Living on the Edge: Household Registration Reform and Peri-Urban Precarity in China. J. Urban Aff. 2014, 36, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; He, D.; Tang, S.; Li, X. Compensation, Housing Situation and Residents’ Satisfaction with the Outcome of Forced Relocation: Evidence from Urban China. Cities 2020, 96, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wei, L.; Gu, J.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y. Benefit Distribution in Urban Renewal from the Perspectives of Efficiency and Fairness: A Game Theoretical Model and the Government’s Role in China. Cities 2020, 96, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, G.; Sheng, B. A Multidimensional Empirical Study on the Social Integration of China’s Migrant Population. Urban Probl. 2020, 6, 4–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Geertman, S. Toward Smart Governance and Social Sustainability for Chinese Migrant Communities. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayoung, P. A Research on Laborer Cultural Realities and Its Related Discourse in China since 2000s: Focusing on Pi Village in Beijiing. Korea J. Chin. Lang. Lit. 2019, 76, 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Dijst, M.; Van Weesep, J. Social Networks of Rural–Urban Migrants after Residential Relocation: Evidence from Yangzhou, a Medium-Sized Chinese City. Hous. Stud. 2017, 32, 816–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pan, L.; Heerink, N. Working Conditions and Job Satisfaction of China’s New Generation of Migrant Workers: Evidence from an Inland City. SSRN Electron. J. 2013, 207, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Leng, C.; Tao, J. Community Field and the Urban Identity of Migrant Workers. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 6, 157–159. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nordin, M. Social Support: Health Benefits from Social Relations. In Supporting Sleep: The Importance of Social Relations at Work; Palgrave Pivot: London, UK, 2015; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, E.G.T. Who Can Enter? A Multilevel Analysis on Public Support for Immigration Criteria across 20 European Countries. Gr. Process. Intergr. Relat. 2009, 12, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fierro, J.; Parella, S. Social Trust and Support for Immigrants’ Social Rights in Spain. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayor, R.H.; Molina, N.; Tsuchiya, K. Transnational Encounters: Immigration, Race, and Citizenship in Encountering Ellis Island, How Race Is Made in America, and Reinventing Citizenship. J. Urban Hist. 2017, 43, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.M.; Konerding, V.; Nautiyal, S.; Buerkert, A. Is the Push-Pull Paradigm Useful to Explain Rural-Urban Migration? A Case Study in Uttarakhand, India. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandercasteelen, J.; Tamru, S.; Minten, B.; Swinnen, J.F.M. Cities and Agricultural Transformation in Africa: Evidence from Ethiopia. World Dev. 2016, 105, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Leng, C.; Tao, J. Measuring the Level of Welfare of Migrant Workers Moving to Cities under a Viable Capacity Framework. Urban Probl. 2020, 6, 73–82. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xing-Yan, D.; Zhong-Bin, L. Research on the Intergenerational Flow of Migrant Workers’ Education. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2020, 17, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. Psychol. Intergr. Relat. 1986, 1, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mangum, M.; Block, R. Social Identity Theory and Public Opinion towards Immigration. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janker, J.; Vesala, H.T.; Vesala, K.M. Exploring the Link between Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Identities and Work Wellbeing. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 83, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y. A Study on the Impact of Local Attachment on Community Participation of Urban Residents—The Case of Guangzhou. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2019, 39, 734–741. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Leng, C. Housing Status, Social Status and Migrant Workers’ Urban Identity: An Empirical Analysis Based on Social Integration Survey Data. China Rural Surv. 2018, 1, 96–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J.; Deng, X. Spatial Differentiation and Driving Forces of Migrants’ Socio-Economic Integration in Urban China: Evidence from CMDS. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 159, 1035–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Xin, Z.; Wu, Y.; Qi, S. Community Identity Profiles and COVID-19-Related Community Participation. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 32, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Tian, Z.; Sun, W. The Impacts of City-Specific Factors on Social Integration of Chinese Migrant Workers: A Study Using Multilevel Modeling. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y. Research on Input-Output Efficiency of Junior High School-A Case Study of DEA-OLS Model. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1955, 012121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Escrig, E.; Mallén-Broch, F.F.; Lapiedra-Alcamí, R.; Chiva-Gómez, R. The Influence of Leaders’ Stewardship Behavior on Innovation Success: The Mediating Effect of Radical Innovation. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J. Childhood Maltreatment and Psychological Well-Being in Later Life: The Mediating Effect of Contemporary Relationships with the Abusive Parent. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 73, e39–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, F.; Ezani, M.; Hassan, M.; Mutasim, N.; Ab, N.; Rashid, M.; Hamid, A. Antecedents and Impacts of Service Operations Flexibility: A Multiple Regression Approach. Int. J. Contemp. Bus. Manag. 2008, 1, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X. Influencing Factors on the Willingness to Settle in Cities by Agricultural Transfer Population. Urban Probl. 2016, 3, 89–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Perron, P.; Yamamoto, Y. Using OLS to Estimate and Test for Structural Changes in Models with Endogenous Regressors. J. Appl. Econom. 2015, 30, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Klar, J. Goodness-of-Fit Testing for the Logistic Regression Model When the Estimated Probabilities Are Small. Biom. J. 1988, 30, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdoğan, A.Ç.; Önder, F.C. The Relation between Parents’ Emotional Availability and Reactive-Proactive Aggression in Adolescents: The Intermediary Role of Difficulties in Emotion Regulation. Egit. Bilim 2018, 43, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, L.; An, Y.; Fan, X. The Multiple Mediating Effects of Social Connectedness and Self-Care Confidence on the Relationship between Subjective Social Status and Emotional Well-Being in Patients with Heart Failure: A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2022, 21, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Hu, A.; Lo, J. Two Aspects of the Rural-Urban Divide and Educational Stratification in China: A Trajectory Analysis. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2014, 58, 509–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Lu, M. Beyond Lewis: Rural-to-Urban Migration with Endogenous Policy Change. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 5, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztofik, R.; Dymitrow, M.; Grzelak-Kostulska, E.; Biegańska, J. Poverty and Social Exclusion: An Alternative Spatial Explanation. Bull. Geogr. 2017, 35, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ouředníček, M.; Šimon, M.; Kopečná, M. The Reurbanisation Concept and Its Utility for Contemporary Research on Post-Socialist Cities: The Case of the Czech Republic. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2015, 23, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biegańska, J.; Szymańska, D. The Scale and the Dynamics of Permanent Migration in Rural and Peri-Urban Areas in Poland—Some Problems. Bull. Geogr. 2013, 21, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | Indicators | Indicator Meanings | Ave | S.D. | Min | Max |

| Community integration | / | I would like to integrate with the local people in the community. Totally disagree = 1, disagree = 2, basically agree = 3, completely agree = 4 | 3.27 | 0.625 | 1 | 4 |

| Personal characteristics | Gender | Male = 0, female = 1 | 0.48 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | Actual age | 39.51 | 9.966 | 20 | 86 | |

| Education level | Below junior high school = 1, high school/secondary school = 2, junior college = 3, university undergraduate and above = 4 | The value = 1 (58.31%) The value = 2 (26.22%) The value = 3 (10.39%) The value = 4 (5.08%) | 1 | 4 | ||

| Number of household members | Number of household members | 3.01 | 1.216 | 1 | 10 | |

| Marriage status | Unmarried/cohabiting = 1, divorced/widowed = 2, married = 3 | The value = 1 (21.66%) The value = 2 (76.25%) The value = 3 (2.09%) | 1 | 3 | ||

| Community identity | Self-identity, | I feel like a local already. Totally disagree = 1, disagree = 2, basically agree = 3, totally agree = 4. | 2.79 | 0.751 | 1 | 4 |

| Local acceptance | I think the locals would like to take me on board. Totally disagree = 1, disagree = 2, basically agree = 3, totally agree = 4. | 3.19 | 0.619 | 1 | 4 | |

| Organizational identity | Interact with people in my spare time. Very little interaction with people = 1, with fellow countrymen = 2, other migrants = 3, other locals = 4. | The value = 1 (3.77%) The value = 2 (29.95%) The value = 3 (50.26%) The value = 4 (16.02%) | 1 | 4 | ||

| Social identity | Apply for a personal social security card. Did not do it, never heard of it = 1, did not do it but heard of it = 2, have done it = 3. | 2.30 | 0.742 | 1 | 3 | |

| Community participation | Making suggestions | Give advice or monitor management in the community. No = 1, occasionally = 2, sometimes = 3, often = 4. | 2.95 | 0.270 | 1 | 4 |

| Participating in discussions | Comment on national affairs and social events online and participate in discussions. No = 1, occasionally = 2, sometimes = 3, often = 4. | 2.93 | 0.298 | 1 | 4 | |

| Participating in activities | Active participation in volunteer activities. No = 1, occasionally = 2, sometimes = 3, often = 4. | 2.40 | 0.533 | 1 | 4 | |

| Community concern | Concern about the changes in the community. Totally disagree = 1, disagree = 2, basically agree = 3, totally agree = 4. | 3.29 | 0.612 | 1 | 4 | |

| Variables | Indicators | Panel A: the Entire Sample | Panel B1: the First Generation of ATP | Panel B2: the Second Generation of ATP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal characteristics | Gender | 0.043 (0.027) | 0.027 (0.038) | 0.072 * (0.038) |

| Age | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.004 * (0.003) | 0.007 (0.006) | |

| Education level | 0.063 *** (0.017) | 0.048 * (0.030) | 0.064 *** (0.021) | |

| Number of household members | 0.008 (0.126) | 0.031 (0.019) | −0.024 (0.018) | |

| Marriage status | 0.117 ** (0.039) | 0.029 (0.075) | 0.144 ** (0.055) | |

| Community Identity | Self-identity | 0.318 *** (0.020) | 0.312 *** (0.028) | 0.323 *** (0.028) |

| Local Acceptance | 1.015 *** (0.025) | 1.006 *** (0.035) | 1.031 *** (0.037) | |

| Organizational identity | 0.024 ** (0.011) | 0.019 * (0.015) | 0.032 * (0.016) | |

| Social identity | 0.049 ** (0.018) | 0.047 * (0.025) | 0.045 * (0.026) | |

| Community participation | Making suggestions | 0.564 *** (0.049) | 0.486 *** (0.070) | 0.636 *** (0.068) |

| Participating in discussions | 0.255 *** (0.045) | 0.338 *** (0.069) | 0.194 ** (0.059) | |

| Participating in activities | 0.148 *** (0.026) | 0.188 *** (0.037) | 0.100 ** (0.037) | |

| Community concern | 0.761 *** (0.023) | 0.798 *** (0.033) | 0.721 *** (0.034) | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0319 | 0.3385 | 0.3269 | |

| LR Chi2 | 6115.76 *** | 3162.94 *** | 2962.37 *** | |

| Number of observations | 10,015 | 5021 | 4994 | |

| Variables | Indicators | Alternative to Variables | Alternative Regression Methods | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: the Entire Sample | Panel B1: the First Generation of ATP | Panel B2: the Second Generation of ATP | Panel A: the Entire Sample | Panel B1: the First Generation of ATP | Panel B2: the Second Generation of ATP | ||

| Personal characteristics | Gender | 0.005 (0.023) | 0.026 (0.033) | 0.045 (0.033) | 0.073 (0.050) | 0.065 (0.071) | 0.111 (0.072) |

| Age | −0.010 ** (0.001) | −0.012 ** (0.002) | −0.004 (0.005) | −0.004 (0.003) | −0.009 * (0.005) | 0.015 (0.011) | |

| Education level | 0.132 *** (0.015) | 0.189 ** (0.026) | 0.096 *** (0.018) | 0.107 ** (0.032) | 0.090 ** (0.056) | 0.106 *** (0.040) | |

| Number of household members | 0.005 (0.011) | 0.004 (0.017) | 0.009 (0.016) | 0.010 (0.024) | 0.041 (0.035) | 0.042 (0.034) | |

| Marriage status | 0.141 *** (0.033) | 0.130 * (0.641) | 0.104 ** (0.047) | 0.209 ** (0.072) | 0.011 * (0.140) | 0.246 ** (0.102) | |

| Community identity | Self identity, | 0.022 ** (0.010) | 0.031 * (0.013) | 0.010 * (0.014) | 0.044 * (0.020) | 0.036 * (0.028) | 0.060 * (0.030) |

| Local acceptance | 0.170 *** (0.023) | 0.213 *** (0.032) | 0.123 *** (0.032) | 1.965 *** (0.050) | 1.957 *** (0.070) | 1.985 *** (0.071) | |

| Organizational identity | 0.152 ** (0.017) | 0.145 *** (0.025) | 0.161 *** (0.024) | 0.563 *** (0.038) | 0.554 *** (0.054) | 0.574 *** (0.053) | |

| Social identity | 0.035 * (0.016) | 0.021 * (0.022 | 0.076 ** (0.023) | 0.090 ** (0.034) | 0.076 * (0.047) | 0.093 * (0.049) | |

| Community participation | Making suggestions | 0.237 *** (0.045) | 0.107 ** (0.064) | 0.365 *** (0.064) | 1.002 *** (0.094) | 0.846 *** (0.132) | 1.163 *** (0.135) |

| Participating in discussions | 0.095 ** (0.041) | 0.240 *** (0.065) | 0.150 ** (0.0540 | 0.458 *** (0.086) | 0.613 *** (0.134) | 0.346 ** (0.114) | |

| Participating in activities | 0.082 *** (0.022) | 0.035 * (0.032) | 0.127 ** (0.032) | 0.270 *** (0.048) | 0.319 *** (0.069) | 0.206 ** (0.069) | |

| Community concern | 0.180 *** (0.022) | 0.147 *** (0.032) | 0.212 *** (0.031) | 1.473 *** (0.046) | 1.534 *** (0.065) | 1.405 *** (0.066) | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.3560 | 0.3630 | 0.3531 | 0.3529 | 0.3596 | 0.3476 | |

| LR Chi2 | 2756.01 *** | 1968.4 *** | 1812.7 *** | 1503.17 *** | 1360.06 *** | 1149.87 *** | |

| Number of observations | 10,015 | 5021 | 4994 | 10,015 | 5021 | 4994 | |

| Resulting Variables | Predictive Variables | Fitted Indicators | Sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | F Value | T Value | p Value | ||

| Community integration | Community participation | 0.31 | 74.46 *** | 5.39 | 0.0000 *** |

| Community identity | Community participation | 0.27 | 203.9 *** | 4.52 | 0.0000 *** |

| Community integration | Community identity | 0.35 | 268.5 *** | 3.21 | 0.0000 *** |

| Community participation | 6.68 | 0.0000 *** | |||

| Items | Effect | Boot SE | T Value | 95% Confidence Intervals | Relative Effects% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| Total effect | 0.827 | 0.062 | 2.729 *** | 0.480 | 0.793 | 100% |

| Direct effect | 0.366 | 0.050 | 6.678 *** | 0.238 | 0.435 | 44.26% |

| Indirect effect | 0.461 | 0.041 | / | 0.256 | 0.389 | 55.74% |

| Reasons | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Better personal development | 2640 | 36.5 |

| Better educational opportunities for the children | 1670 | 23.1 |

| Access to higher income | 1450 | 20.0 |

| Access to public services such as transport and health | 1005 | 13.9 |

| Local social network | 245 | 3.4 |

| Other | 224 | 3.1 |

| Total | 7234 | 100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, J.; Hua, W.; Tang, D.; Liu, F. Sustainable Community Transformation and Community Integration of Agricultural Transfer Population—A Case Study from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137737

Shi J, Hua W, Tang D, Liu F. Sustainable Community Transformation and Community Integration of Agricultural Transfer Population—A Case Study from China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137737

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Jiangang, Wenwen Hua, Daizhong Tang, and Fang Liu. 2022. "Sustainable Community Transformation and Community Integration of Agricultural Transfer Population—A Case Study from China" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137737

APA StyleShi, J., Hua, W., Tang, D., & Liu, F. (2022). Sustainable Community Transformation and Community Integration of Agricultural Transfer Population—A Case Study from China. Sustainability, 14(13), 7737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137737