Abstract

Any program intended to equip the populace, particularly young people, to combat climate change and its repercussions must include education. As crucial stakeholders in education, teachers have the primary responsibility of preparing young people to deal with the effects of climate change. In two districts of Ghana’s Bono region, the study assessed SHS teachers’ viewpoints on climate change and their willingness to include climate change concerns in classes. The degree to which climate change was incorporated into the syllabi of selected disciplines was also assessed. For this study, data was collected from a hundred (n = 100) SHS teachers from 10 of the 15 schools in the study area using a simple random sampling method. The Pearson chi-square test was used to examine the association between the subject content and teachers’ desire to teach climate change. The data were analyzed using SPSS (v25). The findings demonstrated that teachers’ readiness to educate about climate change was influenced by the subjects they taught. Subjects that were not science-based provided little information on climate change to teachers. Climate change is addressed in many areas in Integrated Science and Social Studies, and it is a core topic for all students. Climate change should be taught using an interdisciplinary approach, and in-service training for teachers could be beneficial.

1. Introduction

In comparison to pre-industrial levels, climate change has resulted in a worldwide temperature increase of about 1.1 degrees Celsius [1]. Several worldwide initiatives, particularly in emerging economies, have galvanized and intensified efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change on global development. This paper assessed the perspectives of SHS teachers on their willingness to incorporate climate change concerns in their lessons. The degree to which climate change was incorporated into the syllabi of selected disciplines was also assessed. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC—Paris Agreement), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 13, and the International Climate Action are all part of these global initiatives. Individual countries’ nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and policies, such as Ghana’s Climate Change Policy, are also oriented toward combating climate change’s effects.

Even with the worldwide effort to advance climate change education and communication (CCE), there is still a scarcity of global data that can be used to track or set targets for individual country development [2]. Every four years, the UNFCCC requires member countries to report on their progress, including on education and communication, but there are no precise rules, and most countries lack procedures for collecting CCE data.

Education is a crucial component of any program aiming at equipping the people to combat climate change and its repercussions, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization [3]. Without education, “adaptation”, and “mitigation”, the two contemporary approaches to tackling climate change, little can be done to mitigate climate change and its negative repercussions. According to the research of [4,5], education is the most powerful tool for engaging teenagers and preparing them for jobs in greener economies. Indeed, since 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change has recognized the importance of “education, training, public awareness, public involvement, and public access to information” to limit harmful human interference with the climate system [6] (Article 6).

Furthermore, education will give citizens information and understanding of climate change challenges, as well as ensure the successful implementation of numerous programs at the local, national, and worldwide levels [7]. Education also clarifies the indisputable science and facts regarding humanity’s most pressing dilemma and the future of young people. Students would be better equipped to understand climate change challenges and embrace environmentally sustainable lifestyles if their understanding was improved [8]. Education is the best investment, and very little can be accomplished without it when it comes to global concerns like climate change. Many developing countries are grappling with the question of how and where to begin teaching their citizens.

While climate change knowledge is now readily accessible, Ghana and much of Africa are still lagging in adapting effectively. Ref. [9] found that there is sparse research in Africa on climate change education to support policy This condition is partly attributed to by a widespread lack of public understanding and appreciation of the triggers, consequences, and climate change adaptation approaches. Given that 22.4% of Ghana’s population is between the ages of 10 and 19 [10], providing them with appropriate climate change awareness in a school setting will reduce their vulnerability to potential threats while fostering long-term growth for the society in which they live.

Much of climate change education (CCE) effectively occurs in a structured school system’s curriculum; its coordination depends mainly on one primary stakeholder—the instructor [11]. Teachers constitute a critical part of the education system; they are at the forefront of determining and adjusting the learning materials, experiences, and speed that pupils require to progress through programs that ensure they learn effectively [12]. As the social, cultural, and environmental repercussions of global climate change begin to affect their everyday lives and communities, children and young people are growing up in unpredictable and perilous times [13]. Daily, many young people are exposed to unsustainable patterns of human consumption, population expansion, waste production, habitat loss, pollution, and contamination that exceed the Earth’s ecological systems’ carrying capabilities [14]. Future generations of young people will face enormous challenges as a result of climate change and its repercussions. Understanding the processes and implications of climate change is critical for learners as they remain very vulnerable to the effects of the changing climate. All teachers must be well-informed on climate change to have detailed knowledge transferable to students [15].

Climate change for the most part is taught in science classes, but it must be studied in all subject areas as the issues involved require social, technological, as well as scientific solutions [7].

This current study assessed senior high school (SHS) teachers’ knowledge of climate change and their willingness to incorporate climate change in subjects they teach and determine the extent to which the SHS curriculum covers climate change. The questions this study sought to answer were:

- i.

- Do SHS teachers understand the concerns surrounding climate change?

- ii.

- Is the teacher’s subject impacting the way climate change problems are taught?

- iii.

- Is climate change appropriately addressed in SHS curricula?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Description of the Study Area

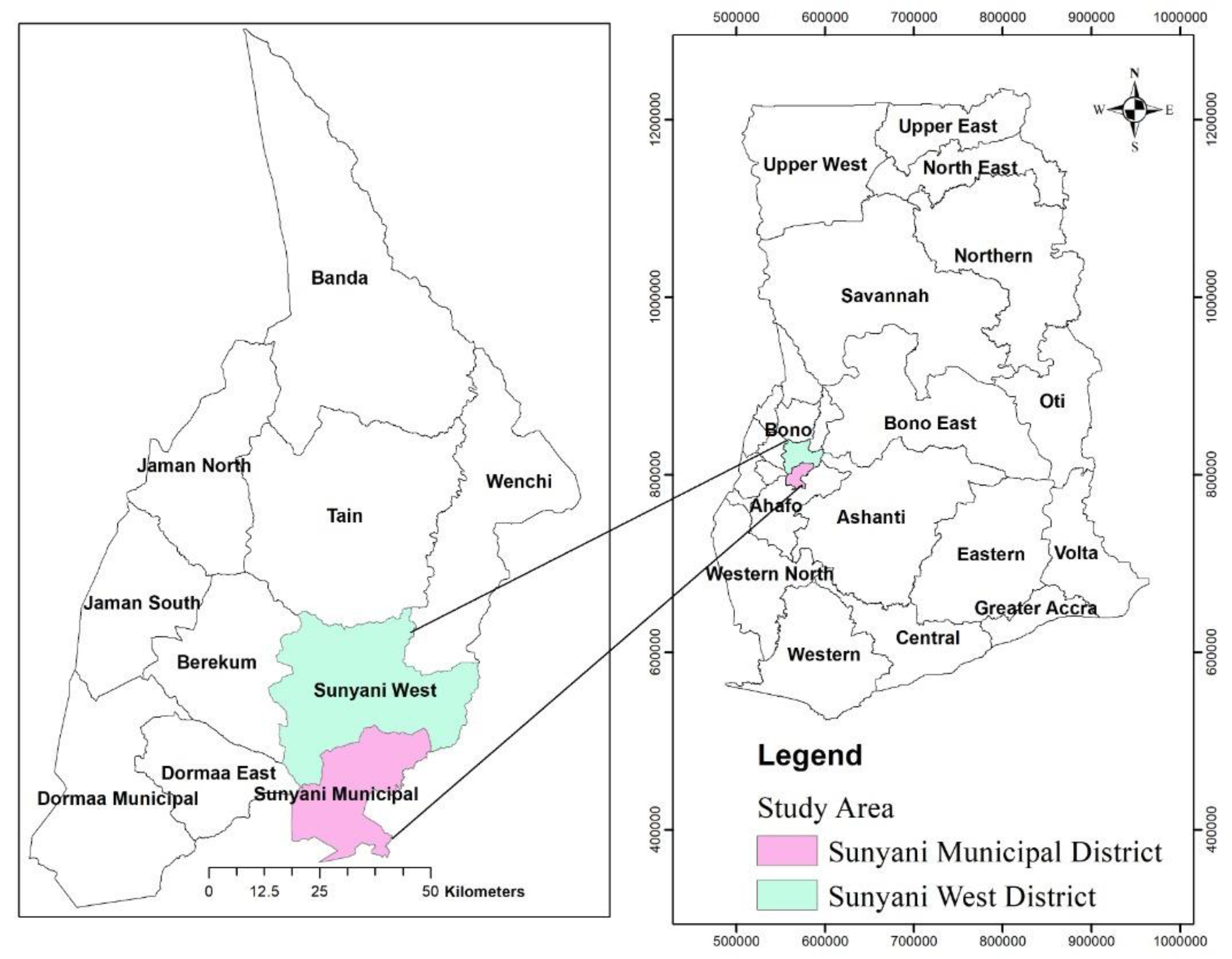

A convergent parallel analysis research design, which is a mixed-method research design, was used in this study. This research was carried out in the Sunyani Municipality and Sunyani West District, one of Ghana’s newly constituted Bono Region’s 11 municipalities and districts (See Figure 1). Because each political region did not include all of the types of senior high schools as defined by the Ghana Education Service (GES) and the West Africa Examinations Council regulations, this study was conducted in both Sunyani Municipality and Sunyani West District. There are five SHS/technical vocational schools in the Sunyani Municipality, and four technical/vocational schools in the business sector. The Sunyani West district has a variety of educational institutions, including seven secondary schools and two universities.

Figure 1.

The research area is depicted on a map of Ghana and the Bono Region.

2.2. Sampling Procedures

Because of the ease of access to the selected schools, the Sunyani Municipality and Sunyani West District were chosen (convenience sampling), however, simple random sampling was used to select the schools for the study. Because the schools in the research region are part of the GES’ Computerized School Selection and Placement System (CSSPS), locating them was simple. Due to the area having a balanced distribution of rural and well-equipped schools, the comparison of instructors is the least skewed. The schools in this study are considered grades 10–12, and they are categorized under the CSSPS as follows:

- Public second cycle institutions were divided into four categories: A, B, C, and D.

- All second cycle schools that provide technical/vocational programs fall into Category E.

- Senior high/technical vocational institutions (Categories F and G) private schools.

Based on the CSSPS categorization of GES schools, a total sample of n = 100 participants was chosen from 10 of 15 SHS in the area. Each school had ten teachers chosen at random. Four of the questionnaires, however, were discarded owing to missing information. The data collection response rate was 96%.

2.3. Data Collection Tools

The study used questionnaires as the major survey instrument to investigate the association between a teacher’s comprehension of climate change concerns, climate change integration in lessons, and the level of integration of climate change topics in SHS curricula. When assessing the relationship between the teacher and his level of climate change understanding, no assumptions were made.

2.4. Data Analysis and Management

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to conduct descriptive statistical analysis (SPSS v25). For all qualitative analyses, NVivo v11 was employed. For statistical analysis p < 0.05 and a confidence interval (CI) of 95% were recognized as statistical significance for the current study

The amount of climate change integration was assessed in the syllabi of two core subjects (Integrated Science and Social Studies) and two elective subjects (Geography and Agricultural Science) to provide recommendations where warranted. These subjects were chosen because they are required of all SHS students and cover a wide range of themes, including climate change. Climate change portions are covered in General Agriculture and Geography, which are elective studies.

The objectives, content, teaching, and learning activities were all examined to see if they included climate change awareness [13,14,15]. The syllabus components acted as content analysis analytical units. For each curriculum, the percentage of units covering climate change subjects was calculated. The proportion was calculated by multiplying 100 by the climate change components divided by the total number of units in the syllabus [15]. The research identified areas of the curriculum that should have addressed climate change but did not.

2.5. Ethical Consideration

The Department of Educational Innovations in Science and Technology approved this study. The participants were assured anonymity and confidentiality of the data they provided.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Males made up 76 percent (n = 73) of the respondents, while females made up 24 percent (n = 23). The majority of responders (46.2 percent, n = 44) were between the ages of 20 and 30. (see Table 1). All instructors at the secondary school level must hold a bachelor’s degree, according to the Ghana Education Service. As a result, the vast majority of responders (95%, n =91) had a Bachelor of Science or Bachelor of Arts degree (see Table 1). Climate change was discussed by all of the respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents.

3.2. Level of Awareness of Climate Change Issues among SHS Teachers

Sources of Information on Climate Change

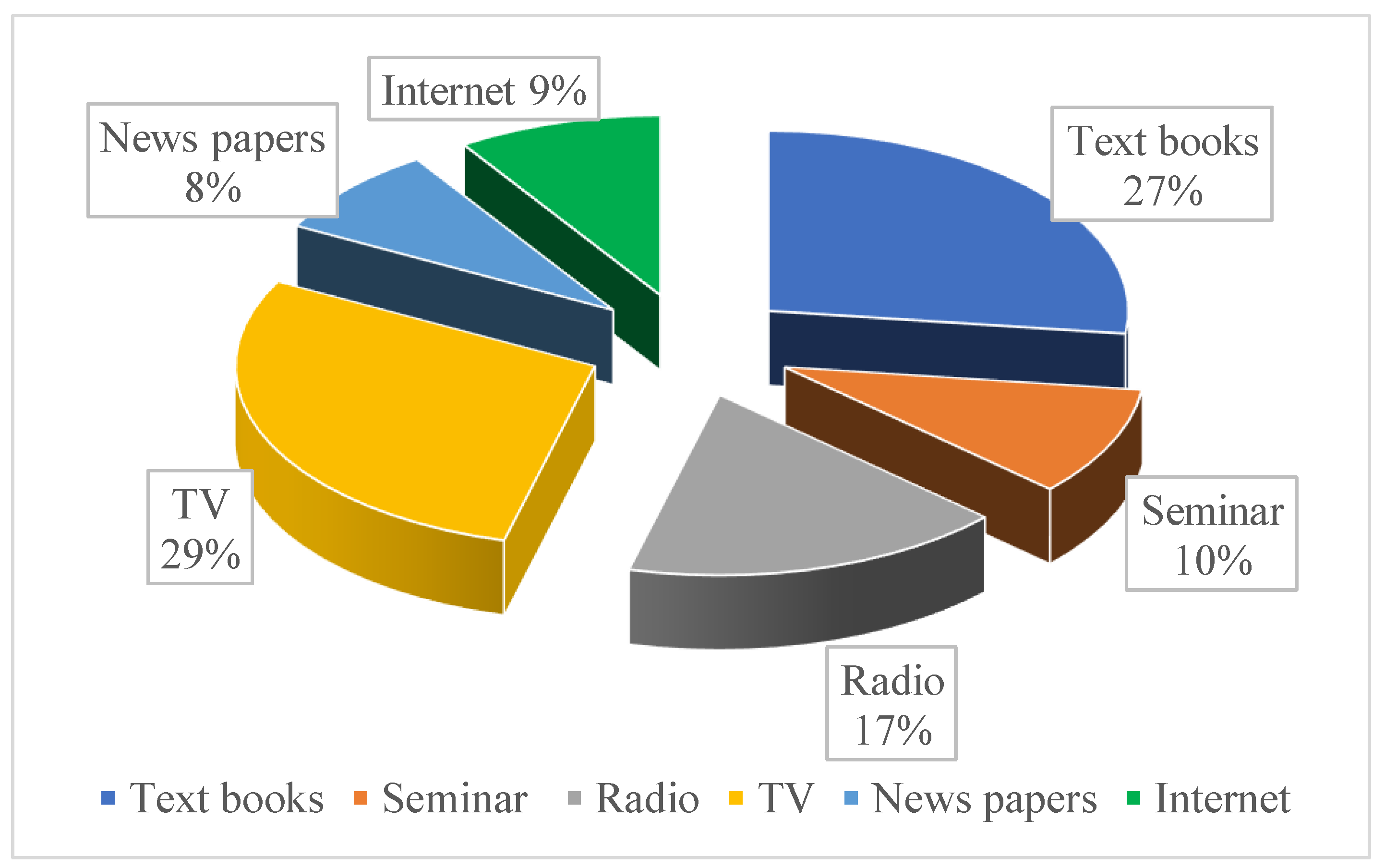

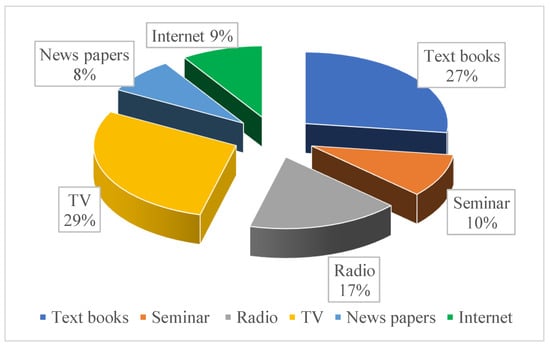

Respondents were asked about the sources from which they obtain climate change information. Television was the most essential source of information for respondents, accounting for 29 percent (n = 28) (see Figure 2). Newspapers were the least reliable source of information, accounting for 8 percent, (n = 8).

Figure 2.

Sources of information on climate change.

3.3. Teachers’ Knowledge of the Causal Nexus of Climate Change Based on the Subject Taught

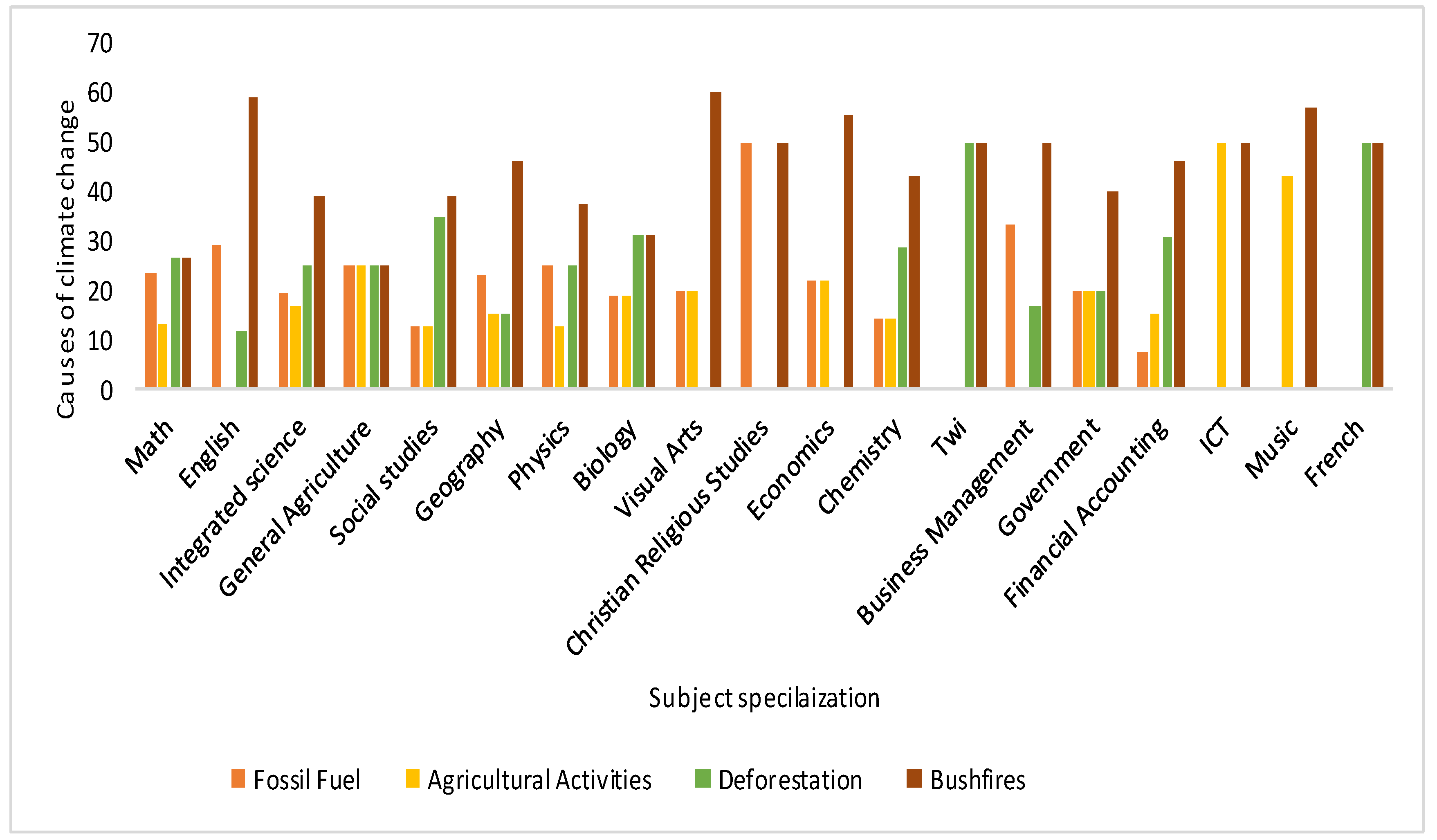

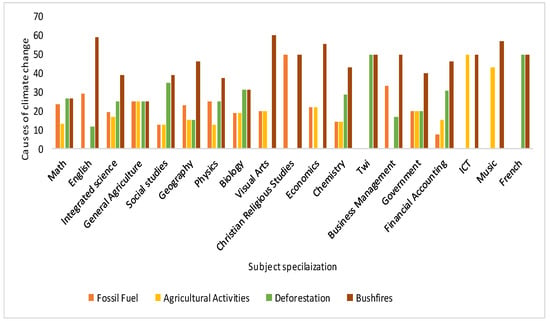

Based on the subject taught, the study examined respondents’ knowledge of the causative nexus of climate change. The findings show that specific subjects taught affect students’ awareness of climate change (p = 0.012). Climate change has a causal relationship, according to respondents who work in Integrated Science and Social Studies. The majority of non-science instructors (60%), for example, did not have in-depth knowledge of climate change. The use of fossil fuels as the main driver of climate change was not mentioned in the syllabi of the responders who teach ICT, Music, or French. Respondents who dealt with languages (English, Twi, and French) and business courses (Management and Financial Accounting) were similarly unaware that expanding agricultural activities are a big source of climate change, according to the findings (see Figure 3). Although deforestation is a major contributor to climate change, responders in the Visual Arts, Christian Religious Studies, Economics, Information Technology, and Music did not concur. Surprisingly, 100% of the respondents agreed that bushfires are a major contributor to climate change.

Figure 3.

Teachers’ knowledge of causes of climate change based on the subject taught.

Respondents were asked if they have encountered climate change challenges in the curriculum of the disciplines they taught (Table 2). Subjects had a substantial impact (p = 0.012) on teachers’ willingness to include climate change problems in classes, according to the response.

Table 2.

Teachers’ knowledge of climate change is based on the syllabus of the subject taught.

3.4. Influence of Subject Specialization on the Teaching of Climate Change

The study looked at the impact of the respondents’ subject on whether or not climate change issues should be discussed in class. A chi-square test revealed a high association (p = 0.001) between the subject dealt with and a teacher’s readiness to incorporate climate change issues into lessons (Table 3).

Table 3.

Influence of subject specialization on the teaching of climate change by teachers.

3.5. Incorporation of Climate Change in Teaching Lessons

Given the importance of climate change, respondents were asked if they would be ready to teach or include it in courses even if it was not on their subjects’ syllabi (Table 4). The chi-square statistic (p = 0.548) revealed no significant link between those who wanted to include it and those who did not. On the other hand, the majority of respondents said that they would be willing to include climate change in their lessons.

Table 4.

Teachers’ willingness to include climate change in their lessons.

3.6. Introduction of Climate Change in the School Syllabus

The appropriate degree for including climate change within SHS teachings is still contested. The majority of respondents (59.8%, n = 57) agreed that climate change should be taught throughout high school (see Table 5), while just 2.1% (n = 2) said it should only be taught in the third year.

Table 5.

Level to introduce climate change in SHS (n = 96).

3.7. Content Analysis of Selected SHS Syllabi for Climate Change

Climate change is covered in SHS courses such as Agricultural Science, Biology, Integrated Science, Social Studies, and Geography. However, some of the subjects are electives, and not all students can take them. All SHS students take Integrated Science and Social Studies as their core topics. Climate change is covered in elective courses such as Geography, Biology, and Agricultural Science. The column titled “Potential topics that could cover climate change” are suggestions that could increase the proportion of content that covers climate change

When the 23 units of the three-year Social Studies curriculum were examined, none of them directly addressed climate change. On the other hand, 6 parts would be sufficient to study climate change over a student’s three years at SHS (Table 6).

Table 6.

Content analysis of Social Studies for topics in climate change.

There were 50 modules in the three-year Integrated Science syllabus. Only 4.8 percent of the 21 units in the first year actively addressed climate change, while 4 other units could do so (Table 7). There was no unit in the second year that expressly addressed climate change; however, there was 1 that had the potential to do so. For the third year in a row, 9.1% of the 11 units dealt with climate change, with 1 more unit potentially dealing with the subject.

Table 7.

Content analysis of Integrated Science for topics in climate change.

The Geography syllabus comprised a total of 24 units, and climate change was covered in 12.5 percent of the first-year syllabus’s 8 sections (see Table 8). Climate change was not featured in any of the second-year units, but 14.3 percent of the 7 units in the third-year syllabi did cover climate change.

Table 8.

Content analysis of Geography for topics in climate change.

The General Agriculture syllabus had 45 units, and the study revealed that climate change was not addressed in the first and second years (Table 9). Only in year three is climate change clearly stated in Sec. 1 (Unit 1.1.3—Content), which is covered under sustainable agriculture and sound agricultural practices, which accounts for 11.1 percent of the curriculum.

Table 9.

Content analysis of General Agriculture for topics in climate change.

3.8. Challenges to the Teaching of Climate Change in Schools

Several difficulties make incorporating and teaching climate change in schools difficult. Insufficient in-service training, a poor average of climate concerns in the teaching syllabus, and a lack of policy and budgetary allocation to promote climate change research, according to the respondents, are the most significant challenges impeding the teaching of climate change (Table 10).

Table 10.

Challenges to teaching climate change in SHS.

4. Discussion

4.1. Sources of Information on Climate Change

Teachers learned about climate change from a variety of sources, according to the study. This conclusion is in line with the findings of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research [16]. Audiovisuals, manuals, teachers’ resource guides, specific web-based lessons, training modules, and books, according to UNITAR, are essential sources of climate change information for high school teachers. Due to a lack of access to technology such as laptops and adequate internet connectivity at the time of the study, ref. [17] discovered that textbooks and instructors’ guides were the primary sources of climate change information. Educators can now rely on a wide range of media, maps, simulations, websites, television shows, movies, field trips, and experiments as sources of climate change information, in addition to printed resources and teacher’s manuals. Ref. [18] published a report in 2010 that stated: Teachers’ pedagogical competence may develop as a result of the various resources available to them, allowing them to construct classes that enhance student involvement in science education. According to literature from Sub-Saharan African countries, resources are vital, and the textbook, which serves as a training tool for teachers and students, is the most important input [19]. The availability of textbooks has a large and favorable impact on learning outcomes, according to [20]. In the case of textbooks in Ghana, for example, current material on climate change may be lacking because they are rewritten every six or seven years on average.

4.2. Main Causes of Climate Change and Teachers’ Knowledge

The views expressed by respondents on the main causes of climate change are in line with the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (2012) [21]. Agricultural activities, deforestation, and other land-use changes all contribute considerably to climate change, according to [22]. The respondents’ knowledge was based on the strategies outlined in the Ghana National Climate Change Policy and the syllabi of individual subjects.

Teachers’ knowledge of the actions of our climate is critical to their desire to convey the challenges to students. Despite the findings of this study, [23,24,25] indicated that many teachers still struggle to state several common human behaviors that contribute to climate change. Ref. [17] found that numerous high school instructors were unaware of the driving factors, implications, and actions that needed to be taken to respond to and mitigate climate change impacts in a similar report. Again, the findings of a study by [26] found that high school instructors have less-than-ideal knowledge of climate change and environmental issues in general. Ref. [27] highlighted those inconsistencies in measuring causes of climate change among teachers are global, which suggests that high school teachers’ awareness of the causes of climate change is not limited to specific locations. The research that produced these contradictory results is at least eight years old, and developments in technology and access may have improved the current study’s results.

4.3. Impact of Subject Specialization on the Teaching of Climate Change among SHS Teachers

The availability of resources and how they are handled can have a significant impact on the teaching process [2]. The syllabus serves as the major source of essential information for teachers to offer their pupils accurate and unbiased data on a variety of topics. Subject specialization, on the other hand, may limit the flexibility and extent to which teachers may include climate change in their lessons. Respondents’ capacity to teach climate change in their classes may be influenced by the subject they choose.

Mathematics, English Language, Social Studies, and Integrated Science are required of all senior high school students, and 72.7% of Math teachers said they had not seen anything regarding climate change on their syllabus (Table 2). When asked if climate change issues had come up in the syllabus of any of the subjects they taught, 52.1% replied yes. None of them claimed to have come across climate change topics in the English course for responders. Most respondents who taught Integrated Science and Social Studies, on the other hand, indicated that climate change was addressed in their respective curricula. Climate change was not covered in the syllabi of various disciplines, including Twi, Business Management, Government, Financial Accounting, ICT, Music, and French.

The chi-square independence test’s significant value implies that the quality of a subject’s syllabus has a considerable impact on a teacher’s knowledge of climate change. This viewpoint is supported by a study by [28], which claims that climate change is a science that is explained through science courses. In the United States, it is part of the Science curriculum or syllabus for high schools. The findings are further supported by [29]’s research in Ethiopia, which indicated that climate change is an important part of the high school Biology curriculum.

According to [30], it is critical to increase teachers’ capacity to provide students with credible knowledge to properly facilitate climate change education. Developing teachers’ capability entails improving their environmental awareness, providing dedicated resources (syllabi, staff toolkits, lesson templates, and teaching modules), and assisting them in gaining the necessary knowledge to empower and direct pupils.

Climate change may be one of the critical science issues that will require strong social and physical science collaboration to adequately prepare the next generation of leaders and policymakers to understand the underlying causes of climate change and to think about solutions [31,32]. Science-based studies may not be very beneficial in teaching and learning about climate change because it affects all aspects of life on Earth. Climate change is not covered in many senior high school syllabi in Ghana, which is concerning because a large number of students pursuing Arts, Business, Visual Arts, and Technical Education may end up knowing very little about a problem that threatens their survival. Through flexible, interactive, and creative space that stimulates creative thinking and learning through music, art, drama, and dance, the curriculum should assist instructors in rethinking fresh means of framing knowledge about climate change.

4.4. Knowledge of the Causal Nexus of Climate Change Based on the Subject Taught

The survey also evaluated respondents’ knowledge of the causative nexus of climate change based on the subject they work with. The syllabi of the disciplines they teach, such as Information, Communication, and Technology (ICT), Music, and French, did not include reasons for climate change such as the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation, according to respondents. Respondents who work with languages (English, Twi, and French), Business Management, and Financial Accounting were also unaware that expanding agricultural activities are a big driver of climate change, according to the findings (Figure 3). Even though deforestation is a major contributor to climate change, respondents in the Visual Arts, Christian Religious Studies, Economics, Information Technology, and Music did not concur. Surprisingly, 100% of the respondents agreed that bushfires are a major contributor to climate change. This finding is consistent with a study by [33], which indicated that climate change education is more directly associated with learning outcomes in science, whereas it is given less weight in the arts, accounting, and language curricula.

In a study on teachers’ ability to comprehend climate change issues, [34] argued that, without extensive cross-disciplinary teaching tools, it could be difficult for many instructors who are not science-inclined to teach it. Because we have never been in the position we are in now, climate change training is about experiencing firsthand uncertainty, risk, and rapid change. They can no longer guarantee a safe environment for young people because the effects of climate change are affecting industries, natural resources, and socio-economic structures. As a result, climate change must be addressed in all areas so that students are prepared to contribute to its management wherever they end up.

4.5. Influence of Subject Specialization on the Teaching of Climate Change

The current study investigated whether the subjects that respondents were exposed to had any bearing on their readiness to teach climate change issues. According to the findings, approximately half of all respondents stated the subject they were teaching had a significant impact on their willingness to teach climate change (Table 4).

Around 60% of instructors who teach Physics, Biology, Agricultural Science, Social Studies, and Chemistry said that the subject they were teaching influenced their decision to teach climate change problems. Around 60% of teachers who teach Arts and Business disciplines (Business Management, Twi, French, Financial Accounting, and Music) claimed they did not address climate change in their classes because the syllabus did not cover it. Ref. [35] concluded that appropriately preparing for an unfamiliar or only comparatively understood future is a substantial problem for curriculum writers in a parallel study in Australia. However, it appears that the subject’s complexity necessitates curricula and pedagogies that allow teachers to collaborate with their students in understanding the origins of the problem and identifying appropriate paths forward for positive actions.

Many of the respondents expressed worry in informal talks about insufficient instructional hours and chances on the curriculum to address climate change in their classes. This condition shows that if climate change education is limited within existing systems and structured school curriculum spaces, the aims established for it will not be met. However, ref. [36] found that, for those countries that reported a target audience for CCE to UNESCO, over 50% of the references were made to formal education settings. It may need the creation of new informal and extracurricular activities that provide additional learning opportunities. Ref. [37] proposed in their study that the possibility for instructors to engage students in project-based and practical learning projects such as local school farms will help us to learn about climate change in a variety of ways. Student clubs and competitions that offer incentives for students to analyze and respond to local environmental implications of a changing climate could be another means of educating about climate change without overburdening the permitted syllabus. These activities could be a new and extended aspect of a comprehensive education that involves students in community-based research.

4.6. Content Analysis of Selected High School SHS (Grade 10–12) Syllabi for Climate Change

The availability of resources may have a significant impact on teaching. The syllabus serves as a major guide for teachers in providing accurate and fair information to their pupils on a variety of topics. A content study of selected SHS syllabi was conducted to determine the amount of climate change incorporation. The syllabi of core topics, Integrated Science and Social Studies, were compared to those of elective subjects, Geography and General Agriculture.

Despite the fact that the Social Studies syllabus did not specifically address climate change, at least six (6) separate parts may be enhanced to include climate change. The environment, sustainable development, education, and the environment, as well as Ghana’s role and cooperation with the international community, are covered in these sections. Climate change is discussed directly in roughly 6.95 percent of the three-year Integrated Science syllabus, whereas just 6.24 percent of Geography and 6.43 percent of Agricultural Science syllabi covered climate change topics. Although the rate of inclusion appears modest, it is substantially greater than in Kenya, where only 0.53 percent of secondary school curricula explicitly or indirectly addressed climate change [38].

Between 1993 and 2014, according to [20], there was an insufficient integration of climate change topics in the Senior Secondary School Certificate Examination (SSSCE) and West African Senior High School Certificate Examination (WASSCE) items. Climate change has been mentioned in SSSCE (1999), SSSCE (2000), WASSCE (2006), WASSCE (2011), and WASSCE (2014) examinations, which spans only four years. Because the education curricula handle climate change themes only briefly, this trend is expected.

Ref. [39] suggests that improving teachers’ capacity to provide pupils with credible knowledge is critical to successful climate change education. Developing teachers’ capability entails improving their environmental awareness, providing dedicated resources (syllabi, staff toolkits, lesson templates, and teaching modules), and assisting them in gaining the necessary knowledge to empower and direct pupils. According to this study, the quality of a teacher’s curriculum has a substantial impact on their knowledge of climate change.

Climate change is a critical science issue that necessitates strong social and physical science collaboration to adequately prepare the next generation of leaders and policymakers to comprehend the underlying causes of climate change and propose climate change solutions [40,41]. Thus, the omission of climate change in many senior high school curricula in Ghana is concerning. A large number of students pursuing Arts, Business, Visual Arts, and Technical Education may wind up understanding very little about a phenomenon that could have an impact on and risk their survival. Through flexible, interactive, and creative space that stimulates creative thinking and learning through music, art, drama, and dance, the curriculum should assist instructors in rethinking fresh means of framing knowledge about climate change.

Climate change topics should be addressed in all SHS subjects, including Integrated Science, Biology, Geography, Social Studies, History, Language, Music, and the Arts, for students in grades 10–12. When it comes to incorporating climate change into studies, there are various possibilities to consider, and an instructor who is committed to doing so will find a way to make it work. Some respondents believe climate change should be taught in the first year, while others believe it should be taught in the second year. Around two-thirds of those polled felt that climate change should be taught in high school. Climate change is so essential to society, according to the majority of respondents, that it should be taught at all levels of formal education [42]. Ref. [43] discovered that climate change has been widely addressed at all high school levels in Singapore. It became apparent from focus group discussions that national policy on climate change has not been adequately integrated into the curricula. Some went on to suggest that adequate in-serve training could make up for the lapses. However, ref. [44] claims that the complexity of some climate change concepts is beyond the comprehension of primary school students and proposes that climate change be introduced at the high school level.

The study identified potential topics under which climate change could be covered. These potential areas suggest that perhaps the syllabi could have covered more climate change issues than they currently do. This is in line with suggestions made by [20,45,46].

4.7. Challenges to the Teaching of Climate Change

The biggest hurdles to properly teaching the subject, according to respondents, include a lack of in-service training, inadequate climate change issues in the teaching syllabus, and a lack of money for research on climate change education approaches. Despite the fact that Section 2.2.6 of the Ghana National Climate Change Policy [47] emphasizes integrating climate change into formal education curricula, teachers have received very little support in terms of training and resources to teach climate change across topics.

Integrating climate change into the educational system can be a difficult task that necessitates genuine nationalist will, a realistic curriculum development guide, and ongoing work on the part of instructors. According to [48], many countries’ national structures and technological capabilities are insufficient. Furthermore, the funding required to create those capabilities is in short supply. Because formal education is already overburdened, some governments are hesitant to put climate change information in the curriculum.

Other challenges that were mentioned but were not significant compared to the ones mentioned in Table 10 are (mis)information from parents, religious groups, and sources that appear to have greater credibility than educators, students from rural communities have more difficulty accepting CCE than those who live in urban areas, non-correlation between what is taught in school and issues in communities, and time to adequately teach climate change in the classroom.

5. Conclusions

According to the findings, instructors have a general understanding of the issue of climate change based on a variety of sources. The findings imply that non-science teachers have difficulty grasping climate change concepts, which reflects their failure to incorporate them into their lessons. Because the majority of respondents favor climate change education in high schools, efforts should be directed toward policy and interdisciplinary professional development to improve climate change instruction delivery. Furthermore, climate change education should be included in all Colleges of Education curricula to better equip pre-service teachers to deal with it in the classroom. Climate change should be included in all senior high school disciplines, according to curriculum developers. Teachers’ capacity and desire to teach climate change themes in class would be enhanced by regular in-service training and refresher courses.

In addition, the use of digital technology should be encouraged and adapted as it can be a powerful tool for climate change education. In that regard, the government of Ghana has started distributing laptops to primary and high school teachers. The Ministry of Communication and Digitalization is embarking on the Girls in ICT initiative which is exposing girls in rural areas of Ghana to the safe usage of technology to boost their knowledge in digital education.

Further research is needed for a comprehensive climate change curriculum from kindergarten to high school (K-12) based on indigenous knowledge and issues as well as national and international policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Y.O.-F.; methodology, N.Y.O.-F. and H.B.E.; software, N.Y.O.-F.; validation, H.B.E.; formal analysis, N.Y.O.-F.; investigation, N.Y.O.-F. and E.O.-F.; data curation, N.Y.O.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Y.O.-F.; writing—review and editing, N.Y.O.-F., E.O.-F. and E.A.O.; visualization, N.Y.O.-F.; supervision, H.B.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to identity protection/confidentiality reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 Degrees Centigrade, 2014; IPCC Special Report; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- McKenzie, M. Climate change education and communication in global review: Tracking progress through national submissions to the UNFCCC Secretariat. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. World Conference on Education for Sustainable Development, Bonn, Germany. 2009. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Education/Training/Compilation/Pages/21.WorldConferenceonEducationforSustainableDevelopmentBonnDeclaration(2009) (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Ofei-Nkansah, K. Promoting Rights in the Fight Against Climate Change. 2013. Available online: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/ghana/10516.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Dyster, A. In Recent Months, Climate Change Education Has Hit the Headlines. 2013. Available online: http://www.leftfootforward.org/2013/07/education-is-the-key-to-addressing-climate-change/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- UNFCCC. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 1992. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Apollo, A.; Mbah, M.F. Challenges and opportunities for climate change education (CCE) in East Africa: A critical review. Climate 2021, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Global climate change: What has science education got to do with it? Sci. Educ. 2012, 21, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.; Smith, N. Knowledge of climate change across global warming’s six Americas. In Yale University. New Haven, CT: Yale Project on Climate Change Communication; Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Statistical Service. Population & Housing Census Summary Report of Final Results; Ghana Statistical Service: Accra, Ghana, 2010.

- Favier, T.; van Gorp, B.; Cyvin, J.B.; Cyvin, J. Learning to teach climate change: Students in teacher training and their progression in pedagogical content knowledge. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 594–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabback, P. What Makes a Quality Curriculum? In-Progress Reflection No. 2 “on Current and Critical Issues in Curriculum and Learning”; UNESCO International Bureau of Education: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M.; Lakew, Y. Young people and climate change communication. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, J.R.; Engelke., P. The Great Acceleration: An Environmental History of the Anthropocene Since 1945. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Seigner, A.; Stapert, N. Climate change education in the humanities classroom: A case study of the Lowell school curriculum pilot. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousell, D.; Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A. A systematic review of climate change education: Giving children and young people a ‘voice’ and a ‘hand’ in redressing climate change. Child. Geogr. 2020, 18, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, K. Letting the Cat Out of the Bag. The Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT) has Education Programmes that Offer Solutions to Climate Change. 2011. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Bryan%2C+K.+Letting+the+Cat+Out+of+the+Bag.+&btnG= (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Pruneau, D.; Gravel, H.; Bourque, W.; Langis, J. Experimentation with a socio-constructivist process for climate change education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2003, 9, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrig, G.; Campbell, K.; Dalbotten, D.; Varma, K. CYCLES: A culturally-relevant approach to climate change education in native communities. J. Curric. Instr. 2012, 6, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, C. Climate change education: The role of pre-tertiary science curricula in Ghana. Sage Open 2015, 5, 2158244015614611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNITAR. Integrating Climate Change in Education at the Primary and Secondary Level. Resource Guide for Advanced Learning. UN CC Learn. 2013. The Pilot Implementation Phase of the One UN Climate Change Learning Partnership. Available online: https://www.uncclearn.org/wp-content/uploads/library/resource_guide_on_integrating_cc_in_education_primary_and_secondary_level.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Ekpoh, U.I.; Ekpoh, I.J. Assessing the level of climate change awareness among secondary school teachers in Calabar municipality, Nigeria: Implication for management effectiveness. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 1, 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Advancing the Science of Climate Change; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadnia, Z.; Moghadam, F.D. Textbooks as resources for education for sustainable development: A content analysis. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2019, 21, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuller, B.; Clarke, P. Raising school effects while ignoring culture? Local conditions and the influence of classroom tools, rules, and pedagogy. Rev. Educ. Res. 1994, 64, 119–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, K.R.; Allen, M.R.; Barros, V.R.; Broome, J.; Cramer, W.; Christ, R.; Church, J.A.; Clarke, L.; Dahe, Q.; Dasgupta, P.; et al. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Tubiello, F.N.; Salvatore, M.; Golec, C.R.D.; Ferrara, A.; Rossi, S.; Biancalani, R.; Federici, S.; Jacobs, H.; Flammini, A. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land-Use Emissions by Sources and Removals by Sinks; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Why do people misunderstand climate change? Heuristics, mental models and ontological assumptions. Clim. Chang. 2011, 108, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Niyogi, D.; Shepardson, D.P.; Charusombat, U. Do earth and environmental science textbooks promote middle and high school students’ conceptual development about climate change? Textbooks’ consideration of students’ misconceptions. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2010, 91, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sterman, J.D. Communicating climate change risks in a sceptical world. Clim. Chang. 2011, 108, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pradhan, G.C. Environmental awareness among secondary school teachers, a study. Educ. Rev. 2002, 45, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bord, R.J.; Fisher, A.; O’Connor, R.E. Is an accurate understanding of global warming necessary to promote willingness to sacrifice. Risk 1997, 8, 339. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasevic, B.; Trivic, D. Creativity in teaching chemistry: How much support does the curriculum provide? Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2014, 15, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Climate Change Education for Sustainable Development in Small Island Developing States: Report and Recommendations. In Proceedings of the UNESCO Experts Meeting, Nassau, The Bahamas, 21–23 September 2011; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, K. Political agency: The key to tackling climate change. Science 2015, 350, 1170–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semper, R. Promoting Climate Literacy Through Informal Science Learning Environments. 2010. Available online: www.project2061.org/events/meetings/climate2010/includes/media/presentations/SemperAAASClimateChange.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Dalelo, A. Loss of biodiversity and climate change as presented in biology curricula for Ethiopian schools: Implications for action-oriented environmental education. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2012, 7, 619–638. [Google Scholar]

- Bieler, A.; Haluza-Delay, R.; Dale, A.; Mckenzie, M. A national overview of climate change education policy: Policy coherence between subnational climate and education policies in Canada (K-12). J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 11, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oversby, J. Teachers’ learning about climate change education. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 167, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, S.J. Curriculum change and climate change: Inside outside pressures in higher education. J. Curric. Stud. 2012, 44, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J.; Stevenson, R.B.; Wals, A.E.J. Introduction to the special section moving from citizen to civic science to address wicked conservation problems. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 450–455, Eerratum in 12844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The Republic of Kenya. National Climate Change Action Plan: Knowledge Management and Capacity Development. In Chapter 5.0: Integrating Climate Change in Education System; Ministry of Environment and Mineral Resources: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.; Pascua, L. The curriculum of climate change education: A case for Singapore. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 48, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, R.W. Climate change in school: Where does it fit and how ready are we? Can. J. Environ. Educ. (CJEE) 2001, 6, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan, C.R.; Levy, B.L.; Collet-Gildard, L. Global climate change in U.S. high school curricula: Portrayals of the causes, consequences, and potential responses. Sci. Educ. 2018, 102, 498–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Choe, S.; Kim, C. Analysis of climate change education (CCE) Programs: Focusing on cultivating citizen activists to respond to climate change. Asia-Pac. Sci. Educ. 2020, 6, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MESTI. Ghana National Climate Change Policy. 2013. Available online: https://www.un-page.org/files/public/ghanaclimatechangepolicy.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Chambers, R. Participatory Workshops: A Sourcebook of 21 Sets of Ideas and Activities; Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).