Youth, Gender and Climate Resilience: Voices of Adolescent and Young Women in Southern Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

- While 43% of country climate strategies (“NDCs”) referenced women or gender it was largely in the context of women as a vulnerable group rather than contributors to climate change mitigation or adaptation.

- Only three countries’ NDCs make explicit reference to girls; both in the context of their needs rather than competencies and there is only one clear reference to girls’ education.

- Those countries that do attend to issues of future generations tend to be “young” countries—those with a large under-15 population—and climate-vulnerable countries. However, only seven NDCs reference children/youth as stakeholders who should be included as decision makers or in climate action.

- Sixty-eight percent of NDCs talk about education but normally in vague terms, including awareness raising, not targeted at young people, or part of a national curriculum to combat the climate crisis.

- No NDCs formally recognise the contributions that investment in girls’ education could make toward their climate strategy.

- Climate strategies overall concentrate on technological fixes, ignoring social concerns and the contributions that people, particularly girls and young women empowered by education and information, might make.

- What are the impacts of climate change on young women and girls’ lives and futures in Zambia and Zimbabwe, especially on education?

- How are such impacts mediated by gender relations and power?

- How can such impacts be tackled through action and advocacy?

3. Approach and Methods

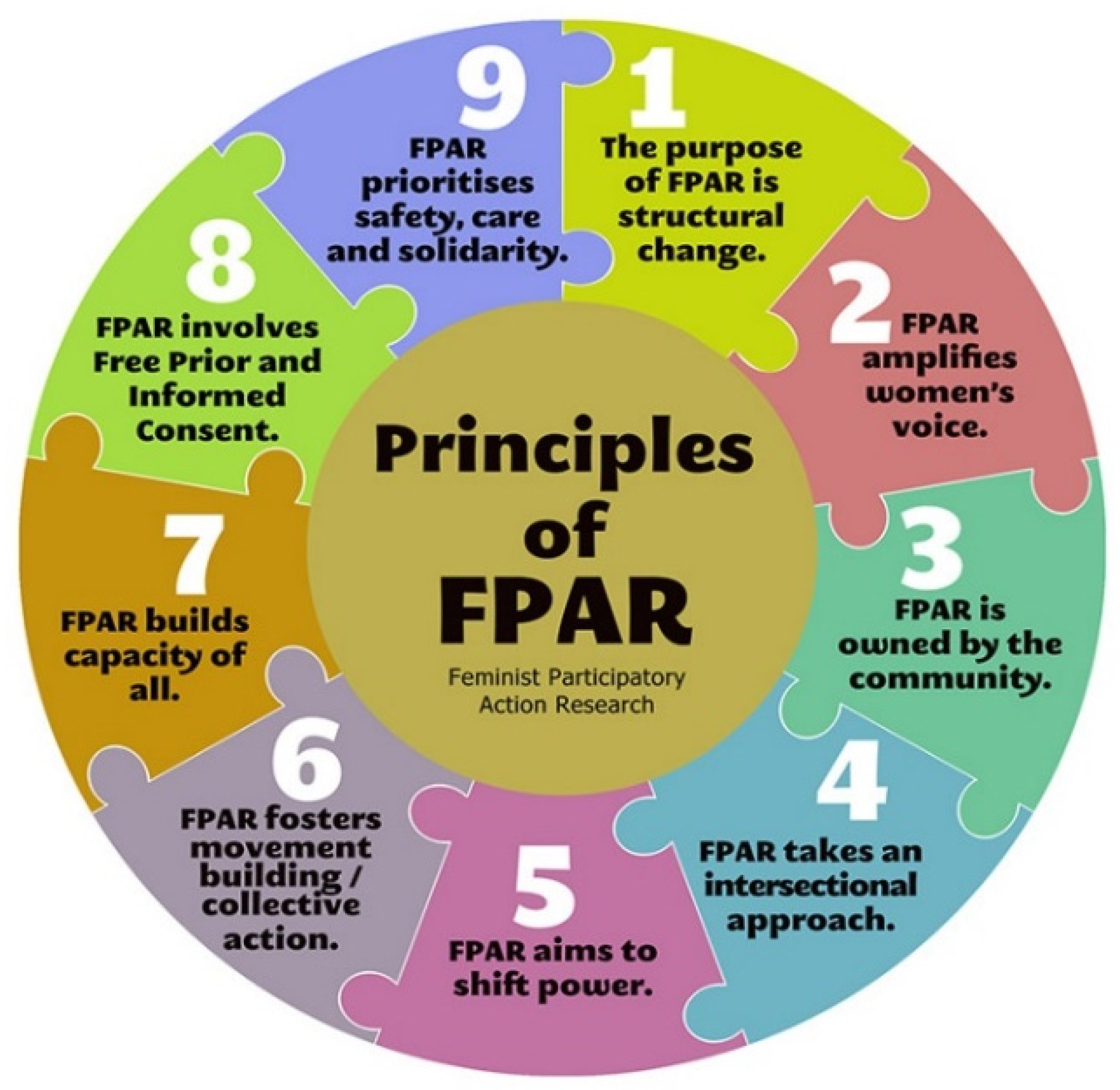

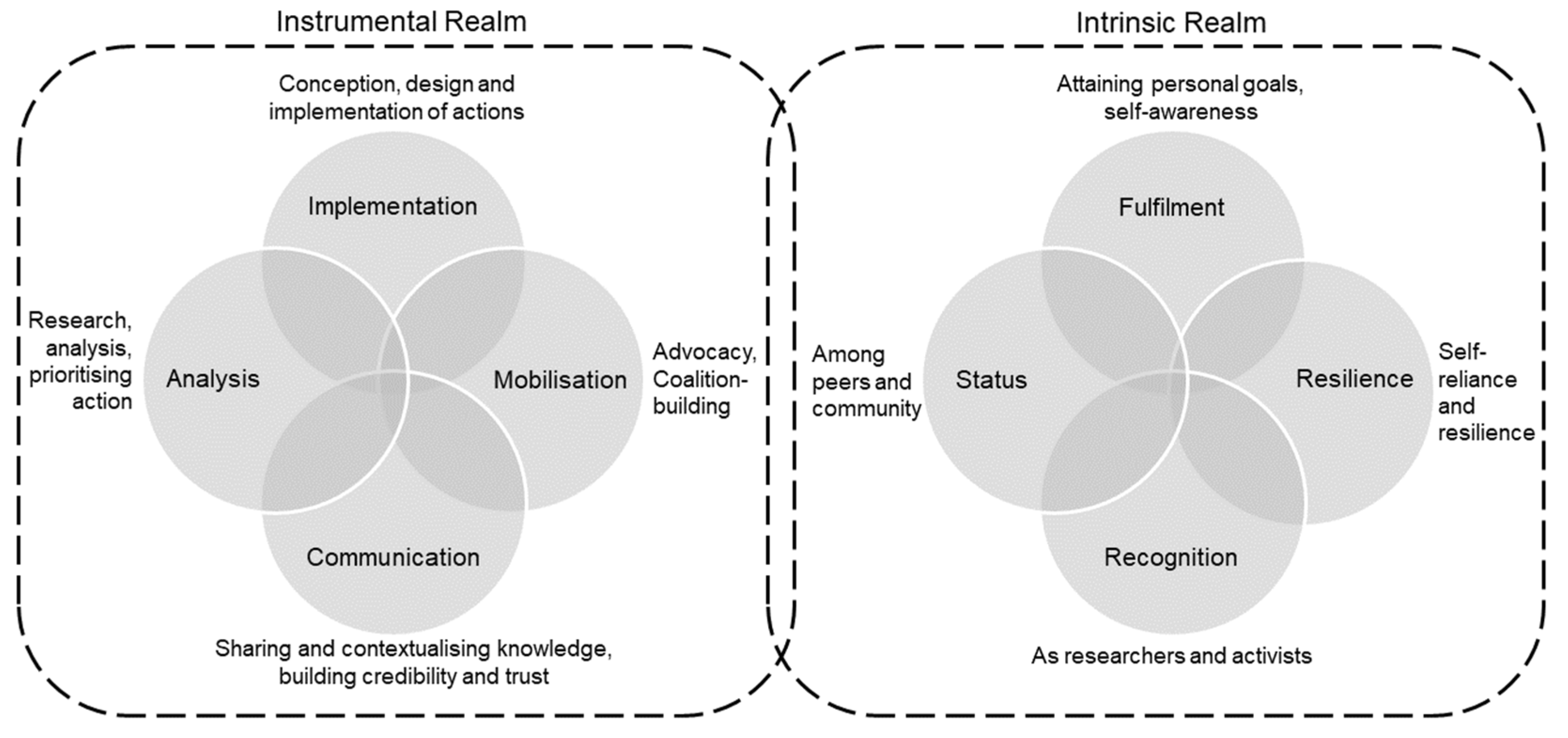

3.1. Conceptual Approach: Feminist Participatory Action Research

3.2. Research Locations

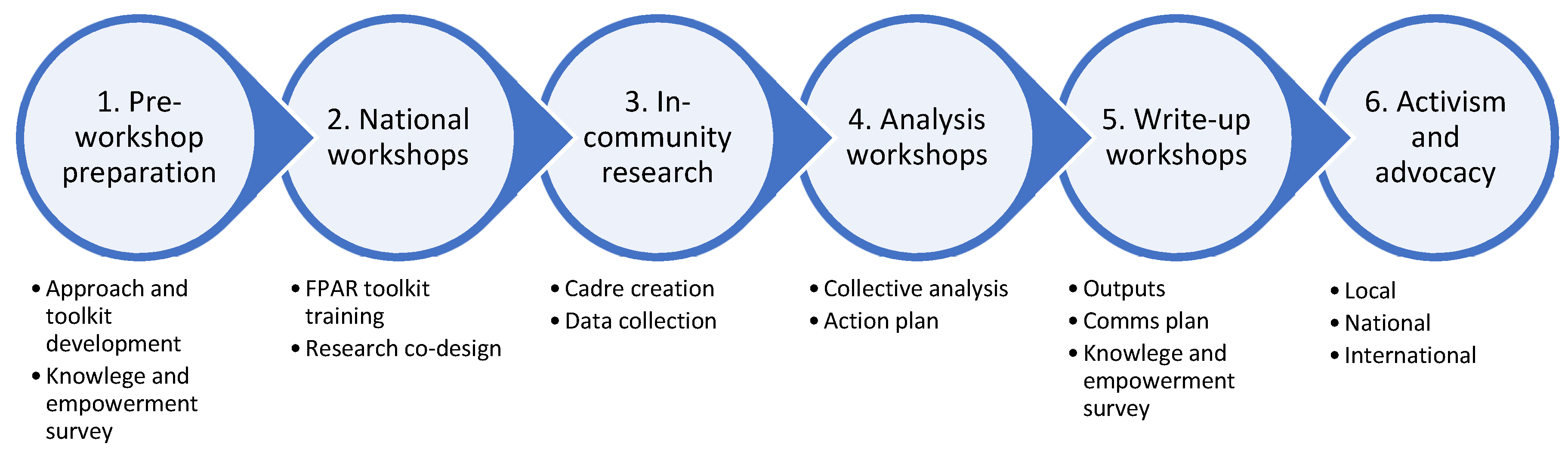

3.3. Research Methods

- Facilitating collective planning of the FPAR process, focusing particularly on collectively developing a roadmap for the research and planning how the different actions will be coordinated.

- Active involvement of young women through a process of sharing their experiences and learning from each other, a continuous process that builds iteratively through the workshops, research, and follow-up. The focus of the research was on the young women as generators of the knowledge—their stories, their experiences, and how they interpret their lived reality.

- Focus on Feminist Popular Education as a way of building critical consciousness. The young women researchers’ understanding of feminism relates to their own lives and how they can use feminist principles to interpret and analyse the world around them.

3.4. Ethics and Safeguarding

4. Results

4.1. Climate, Gender, and Education

“Because of low rainfall received we now share water with animals and that contaminates it making it difficult to maintain a good health and menstrual hygiene”Focus group discussion, Chisamba district, Zambia

“As girls, when the rains destroy our houses, our parents seek shelter on our behalf in the neighbourhood. While there, we are taken advantage of by boys and men living in that house where we will be sheltered”Young Woman Researcher, Zambia

4.2. Climate Adaptation and Advocacy Strategies

“In our community it was difficult to change behavioral issues, norms and values i.e., culture. It was rare to challenge culture especially issues to do with gender balance. Since most interventions in my community were gender blind it wasn’t easy to discuss about these issues.”Patricia, Zimbabwe

4.3. Empowerment and Agency through the FPAR Process

- “I feel so happy, I never knew that someone like me can do research and now I understand better issues of climate change.” Annie, Zambia

- “I am very proud that I helped my community to learn and start discussions on climate change. This process has helped me to gather confidence” Musonda, Zambia

- “I now know that everyone can be a feminist” Penlop, Zambia

- “I never thought I could be a researcher at some point in my life, getting the opportunity to be a feminist researcher was good for my status” IIandra, Zimbabwe

- “Now they call me a feminist in my community” Grace, Zambia

- “I felt very empowered by leading this research using the unique tools and methodology that was easy for people to unpack climate change which l thought was very complex” Faith, Zimbabwe

- “This research enabled young people to be free and share their views, for me I was happy to meet new people and hear how they live their lives. To know the decision making in homes was interesting and how girls challenge this” Mwaka, Zambia.

5. Discussion

6. Concluding Recommendations for Practice and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Plan International. Adolescent Girls in the Climate Crisis: Voices from Zambia and Zimbabwe; Plan International: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nkenkana, A. No African futures without the liberation of women: A decolonial feminist perspective. Afr. Dev. 2015, 40, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, T.; Seballos, F. Action Research with Children: Lessons from Tackling Disasters and Climate Change*. IDS Bull. 2012, 43, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, A.; Bird, D.K.; Ronan, K.; Haynes, K.; Towers, B. Disaster risk reduction education in Indonesia: Challenges and recommendations for scaling up. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 17, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K. Education, Girls’ Education and Climate Change. K4D Emerging Issues Report 29; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kousky, C. Impacts of natural disasters on children. Future Child. 2016, 26, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, A.; Cotton, C. Impact of a Severe Drought on Education: More Schooling but Less Learning; Queen’s Economics Department Working Paper No. 1430; Queen’s University, Department of Economics: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Plan International. Girl Rights in Climate Strategies; Plan International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Djoudi, H.; Locatelli, B.; Vaast, C.; Asher, K.; Brockhaus, M.; Sijapati, B.B. Beyond dichotomies: Gender and intersecting inequalities in climate change studies. Ambio 2016, 45, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNFCCC. Introduction to Gender and Climate Change. Bonn, UNFCCC Secretariat, 2021. Available online: https://unfccc.int/gender (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Tanner, T. Shifting the Narrative: Child-led Responses to Climate Change and Disasters in El Salvador and the Philippines. Child. Soc. 2010, 24, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, A.V.; Van Hoorn, J.; Burke, S.E.L. Responding to the Impacts of the Climate Crisis on Children and Youth. Child Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thew, H.; Middlemiss, L.; Paavola, J. “Youth is not a political position”: Exploring justice claims-making in the UN Climate Change Negotiations. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 61, 102036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Butler, C.; Walker-Springett, K. Moral reasoning in adaptation to climate change. Environ. Politics 2017, 26, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morchain, D. Rethinking the framing of climate change adaptation: Knowledge, power, and politics. In A Critical Approach to Climate Change Adaptation; Klepp, S., Chavez-Rodriguez, L., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Rural Apprasial: Rapid, Relaxed and Participatory; Institute of Development Studies: Falmer, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, S.; Roudbari, S. Who’s learning from whom? Grassroots International NGOs learning from communities in development projects. Dev. Pract. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, T.; Allouche, J. Towards a New Political Economy of Climate Change and Development. IDS Bull. 2011, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Kiteme, B. Concepts and practices for the democratisation of knowledge generation in research partnerships for sustainable development. Évid. Policy J. Res. Debate Pract. 2016, 12, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chakma, T. Feminist Participatory Action Research (FPAR): An effective framework for empowering grassroots women & strengthening feminist movements in Asia Pacific. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 2016, 22, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykes, M.B.; Hershberg, R.M. Participatory Action Research and Feminisms: Social Inequalities and Transformative Praxis. In Handbook of Feminist Research II: Theory and Praxis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 331–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godden, N.J.; Macnish, P.; Chakma, T.; Naidu, K. Feminist participatory action research as a tool for climate justice. Gend. Dev. 2020, 28, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, U. The Historical Evolution of Black Feminist Theory and Praxis. J. Black Stud. 1998, 29, 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriläinen, E.; Kelman, I.; Peters, L.E.R.; Shannon, G. Puppeteering as a metaphor for unpacking power in participatory action research on climate change and health. Clim. Dev. 2021, 14, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Few, R.; Morchain, D.; Spear, D.; Mensah, A.; Bendapudi, R. Transformation, adaptation and development: Relating concepts to practice. Palgrave Commun. 2017, 3, 17092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, C.; Kandy, D.; Turner, J.; Kumar, I.; Pilli-Sihvola, K.; Chanda, F.S. Near-Term Climate Change in Zambia; Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Centre: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- MoEWC. Zimbabwe Third National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Ministry of Environment, Water and Climate, Government of Zimbabwe: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2016.

- Dupar, M. IPCC’s Special Report on Climate Change and Land: What’s in it for Africa? Cape Town: Climate and Development Knowledge Network; Overseas Development Institute and South South North: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, E.; Mtapuri, O.; Matunhu, J. Flooding and poverty: Two interrelated social problems impacting rural development in Tsholotsho district of Matabeleland North province in Zimbabwe. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2018, 10, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxfam-UNDP/GEF. Scaling Up Adaptation in Zimbabwe, with a focus on Rural Livelihoods Project: Profile of Runde/Nuanetsi Sub-catchments in Chiredzi District; Technical Report; Oxfam & UNDP/GEF: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, G.; Molina, F.; Tanner, T.; Seballos, F. Child-friendly participatory research tools. In Community-Based Adaptation to Climate Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Plan International. Child-Centered Multi-Risk Assessments: A Field Guide and Toolkit; Plan International: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Daze, A.; Ceinos, A.; Deering, K. Climate Vulnerability and Capacity Analysis Handbook, 2nd ed.; Care International: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Y-Adapt, Y-Adapt Curriculum; Facilitation Guide; Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre: The Hague, The Netherlands; Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjRobKY54H5AhUNE4gKHVHvD5MQFnoECAQQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.climatecentre.org%2Fdownloads%2Ffiles%2FY-Adapt%2520Curriculum%253B%2520Facilitation%2520Guide%25281%2529.pdf&usg=AOvVaw00oqoF30dbeMtbWLH00Utk (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Rahman, M.A. People’s Self-development, Perspectives on Participatory Action Research, A Journey through Experience; Zed Books: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, G.; Hart, J.; O’Mathúna, D.; Mattellone, E.; Potts, A.; O’Kane, C.; Tanner, T. What We Know about Ethical Research Involving Children in Humanitarian Settings An Overview of Principles, the Literature and Case Studies; Innocenti Working Paper No. 2016-18; UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Plan International Australia. Our Education, Our Future: Pacific Girls Leading Change to Create Greater Access to Secondary Education: Solomon Islands; Plan International Australia: Southbank, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Westholm, L.; Arora-Jonsson, S. What room for politics and change in global climate governance? Addressing gender in co-benefits and safeguards. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 917–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, A.J.; Eriksen, S.; Taylor, M.; Forsyth, T.; Pelling, M.; Newsham, A.; Boyd, E.; Brown, K.; Harvey, B.; Jones, L.; et al. Beyond Technical Fixes: Climate solutions and the great derangement. Clim. Dev. 2019, 12, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woroniecki, S. Enabling Environments? Examining Social Co-Benefits of Ecosystem-Based Adaptation to Climate Change in Sri Lanka. Sustainability 2019, 11, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, F.; Wilbanks, T.; Abeysinghe, A.C.; Burton, I.; Gao, Q.; Lemos, M.C.; Masui, T.; O’Brien, K.L.; Warner, K. Climate-resilient pathways: Adaptation, mitigation, and sustainable development. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Field, C.B., Barros, V.R., Dokken, D.J., Mach, K.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1101–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, E.L.F.; Revi, A.; Preston, B.L. Climate Resilient Development Pathways. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Children in a Changing Climate. Available online: http://www.childreninachangingclimate.org/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Nisbet, M.C. The trouble with climate emergency journalism. Issues Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, K.; Tanner, T.M. Empowering young people and strengthening resilience: Youth-centred participatory video as a tool for climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. Child. Geogr. 2013, 13, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, L.; Abramson, D.M.; Cox, R.S.; Fothergill, A.; Tobin, J. Children and disasters. In Handbook of Disaster Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 243–262. [Google Scholar]

- Trott, C.D. Children’s constructive climate change engagement: Empowering awareness, agency, and action. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 532–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindon, S.; Pain, R.; Kesby, M. Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation and Place. Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, P. Uneven Ground: Feminisms and Action Research. In The Sage Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice; Reason, P., Bradbury, H., Eds.; Sage: London, UK; pp. 59–69.

- Andrijevic, M.; Cuaresma, J.C.; Lissner, T.; Thomas, A.; Schleussner, C.-F. Overcoming gender inequality for climate resilient development. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapfumo, P.; Onyango, M.; Honkponou, S.K.; El Mzouri, E.H.; Githeko, A.; Rabeharisoa, L.; Obando, J.; Omolo, N.; Majule, A.; Denton, F.; et al. Pathways to transformational change in the face of climate impacts: An analytical framework. Clim. Dev. 2015, 9, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung Tiam Fook, T. Transformational processes for community-focused adaptation and social change: A synthesis. Clim. Dev. 2015, 9, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Singh, C.; Solomon, D.; Camfield, L.; Sidiki, R.; Angula, M.; Poonacha, P.; Sidibé, A.; Lawson, E.T. Managing risk, changing aspirations and household dynamics: Implications for wellbeing and adaptation in semi-arid Africa and India. World Dev. 2019, 125, 104667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tool | Details | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

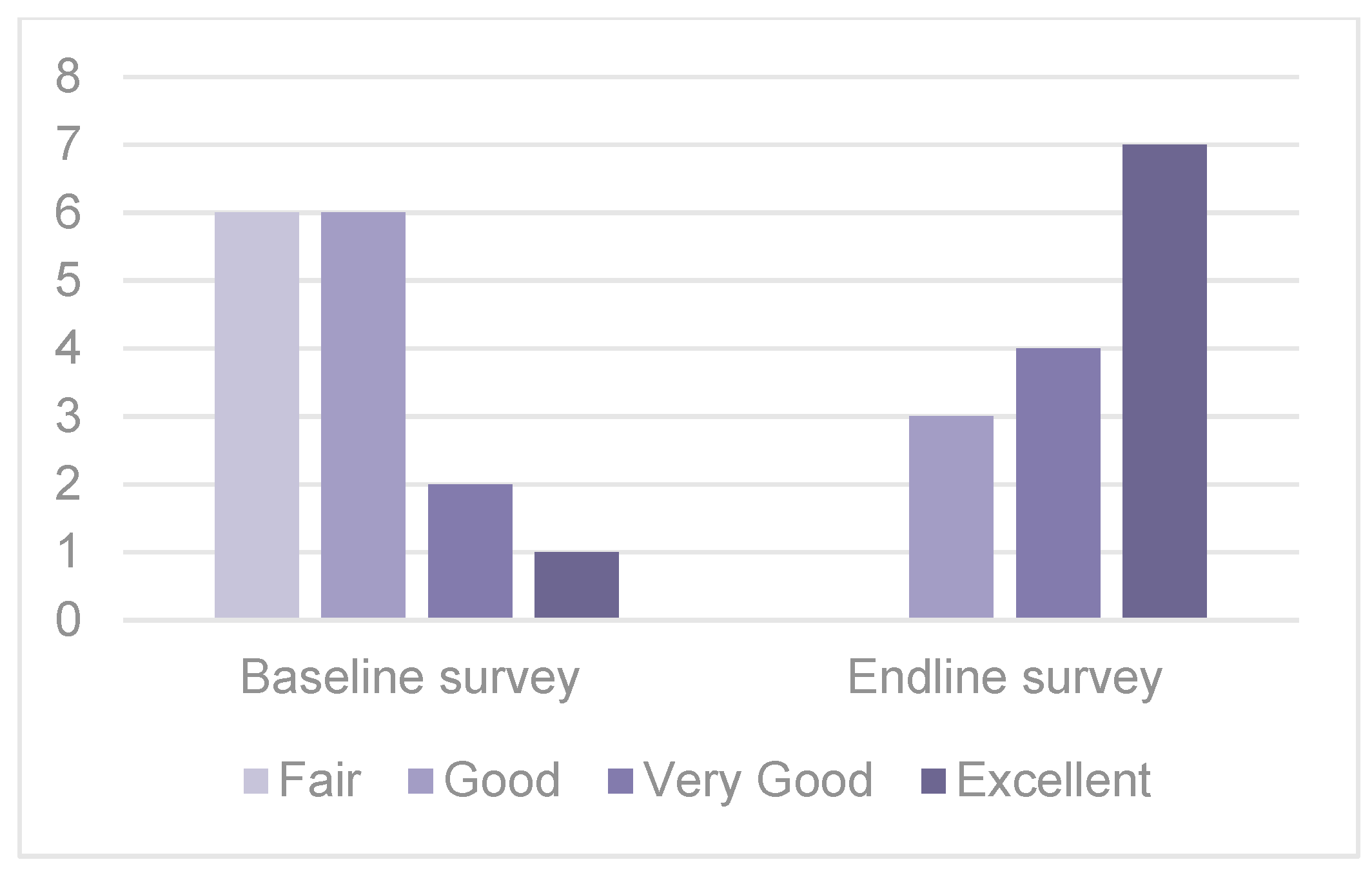

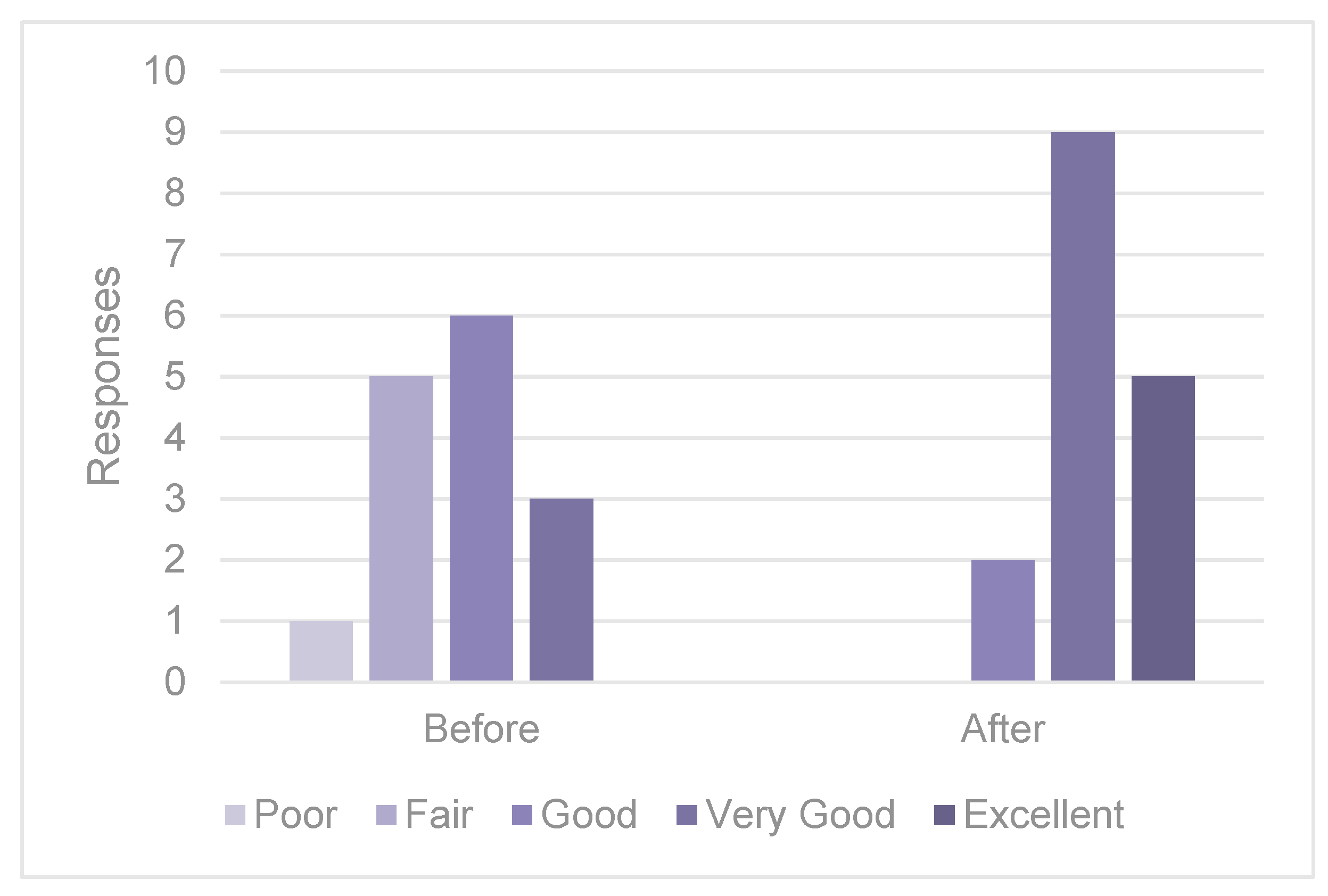

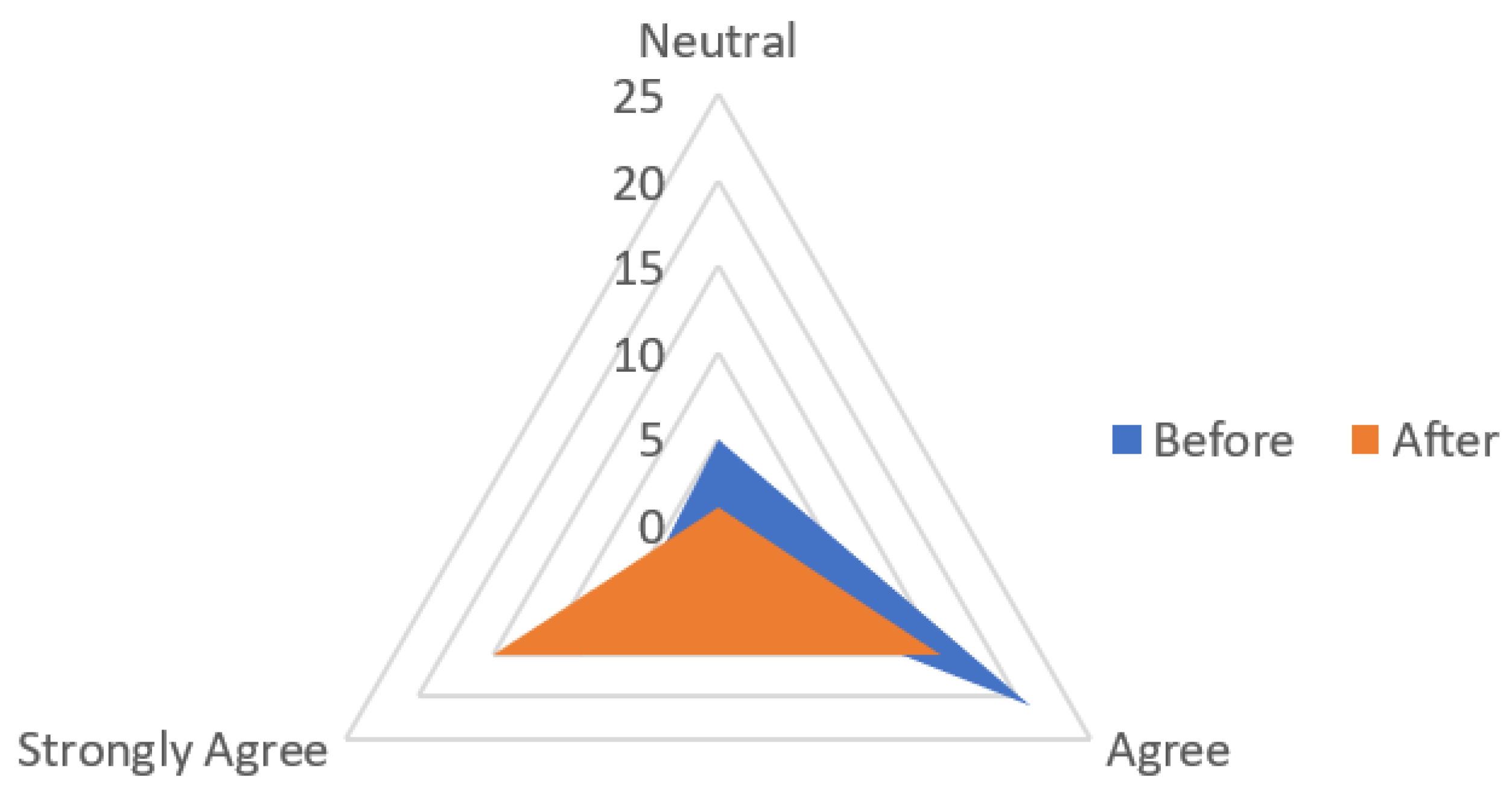

| Online participant survey | Survey carried out online by participants before and after the research process | Capture self-rated language and writing skills to plan facilitation. Capture changes in knowledge and sense of empowerment |

| Reflexive personal journals | Time set aside daily for personal diaries to reflect on personal development, feelings, and the research process. | Tracking and reflecting on processes of knowledge generation and empowerment |

| Feminism 101 | Group exercises | To examine different understandings of feminism |

| Masters House | Interactive exercise to construct and deconstruct a building representing patriarchal structures | To explore the influence of patriarchal structures and how they can be challenged/overcome |

| Visioning exercises | Drawing-based process | To envisage idealised development futures onto which climate impacts can be overlaid |

| Gender pre-assessment | Cobwebs drawing group exercise | To understand the conditions and status of women and girls in the community from a rights perspective |

| Climate change 101 exercises | Physical group-based activities | Physically illustrate the greenhouse effect and climate change impacts |

| Seasonal calendars | Participatory mapping of seasonal activities | Understand local livelihood patterns and seasonality |

| Hazard mapping | Critical thinking challenge to map out extreme weather and its impacts, overlaid onto a seasonal calendar. | Explore the link between climate, hazards, and impacts with a focus on local context; Determine which hazards most affect the community |

| Vulnerability matrix | Matrix-based group exercise | Identify the highest-priority livelihood assets and hazards; Analyse the degree of impact of hazards and changes on priority livelihood assets |

| Impact chains and adaptation pathways | Graphic representations of chains | Analyse direct and indirect impacts of climate change in the community |

| Identify adaptation options to address identified impacts |

| Issue | Targeted Stakeholders | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Low school attendance | Ministry of Education Ministry of Water Development, Sanitation, and Environmental Development | Build more schools so that pupils do not cross rivers. Reschedule school calendar. Build bridges and drainage. Establish satellite schools in flood-prone communities. Provide scholarships to cover school fees for girls. |

| Limited access to water | Ministry of Water and Sanitation | Drill boreholes and provide safe, clean, gender-sensitive water systems and storage. |

| Failing to maintain a livelihood | Ministry of Gender Ministry of Forestry | Empower girls with entrepreneurial skills that are not likely to be affected by climate change. Encourage people to stop cutting down trees. |

| Loss of Crops | Ministry of Agriculture Ministry of Forestry | Provide drought-resistant and water-resistant plants. Enforce policies on cutting down trees. Encourage afforestation and re-afforestation. |

| Destruction of Infrastructure | Ministry of Infrastructure Development | Provide high quality safe and gender-sensitive climate-resilient infrastructure. |

| Contamination of water | Ministry of Water and Sanitation Ministry of Health | Provide safe, clean, and gender-sensitive water systems. Provide chlorine. |

| Vulnerability of girls when seeking shelter | Disaster Management and Mitigation Unit | Provide safe, gender-sensitive temporary shelter for those affected by floods and other disasters, including separate toilets and adequate lighting, and referral systems to easily report or complain where necessary. |

| Low attendance in school due to increased malaria | Ministry of Health; Ministry of Fisheries; Traditional Leaders | Provision of more mosquito nets and gender-sensitive promotion of its use, including through community channels. Implement Fisheries Act to ensure adequate support. |

| Issue | Targeted Stakeholders | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccessibility of schools during extreme weather events such as floods and cyclones: | Ministry of Education; Rural District Council; Member of Parliament; Councillors | Gender budgeting of Community Development Funds (CDF) by Rural District Councils to mirror social needs and concerns of women and girls. Provide fees and transport scholarships for girls. |

| Unequal gender roles between boys and girls | Parents. NGOs. Ministry of Education | NGOs to support capacity building on gender equality. Ministry of Education to mainstream gender equality and climate education in primary and secondary education curricula |

| Access to information on gender equality, disaster early warning systems | Ministry of Information. Mobile Service Providers. District Civil Protection Unit Meteorological Department | Installation of boosters to improve mobile network coverage. Ministry of Information to provide radio and television coverage to areas where this is not available |

| Lack of legal and administrative remedies for survivors of gender-based/sexual violence linked to climate crisis | Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP). Ministry of Justice. NGOs. Traditional Leaders. Church | Girls engage with NGOs to support local ZRP offices to establish and operationalise Victim Friendly Units (VFUs). Girls to work with local NGOs working on GBV to establish referral pathways for survivors |

| Addressing economic vulnerabilities of women and girls | Local NGOs. Local MPs. Local Councillors | Demand local MPs to prioritize climate change responsive economic activities (projects) for women and girls from the Capacity and Delivery Fund (CDF) and other funds.Attend budget consultation meetings for Rural District Councils (RDC) and demand investments in climate change responsive gainful economic activities for women and girls. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tanner, T.; Mazingi, L.; Muyambwa, D.F. Youth, Gender and Climate Resilience: Voices of Adolescent and Young Women in Southern Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148797

Tanner T, Mazingi L, Muyambwa DF. Youth, Gender and Climate Resilience: Voices of Adolescent and Young Women in Southern Africa. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148797

Chicago/Turabian StyleTanner, Thomas, Lucy Mazingi, and Darlington Farai Muyambwa. 2022. "Youth, Gender and Climate Resilience: Voices of Adolescent and Young Women in Southern Africa" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148797

APA StyleTanner, T., Mazingi, L., & Muyambwa, D. F. (2022). Youth, Gender and Climate Resilience: Voices of Adolescent and Young Women in Southern Africa. Sustainability, 14(14), 8797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148797