Research on the Impact of Technical Measures on Enterprise Export Participation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Model

3. Econometric Model

3.1. Model Settings and Variable Descriptions

3.1.1. Model Settings

3.1.2. Variable Description

- (1)

- Explained variable

- (2)

- Core explanatory variables

- (3)

- Control variable

3.2. Data Sources and Sample Composition

3.2.1. Data Sources

3.2.2. Sample Processing

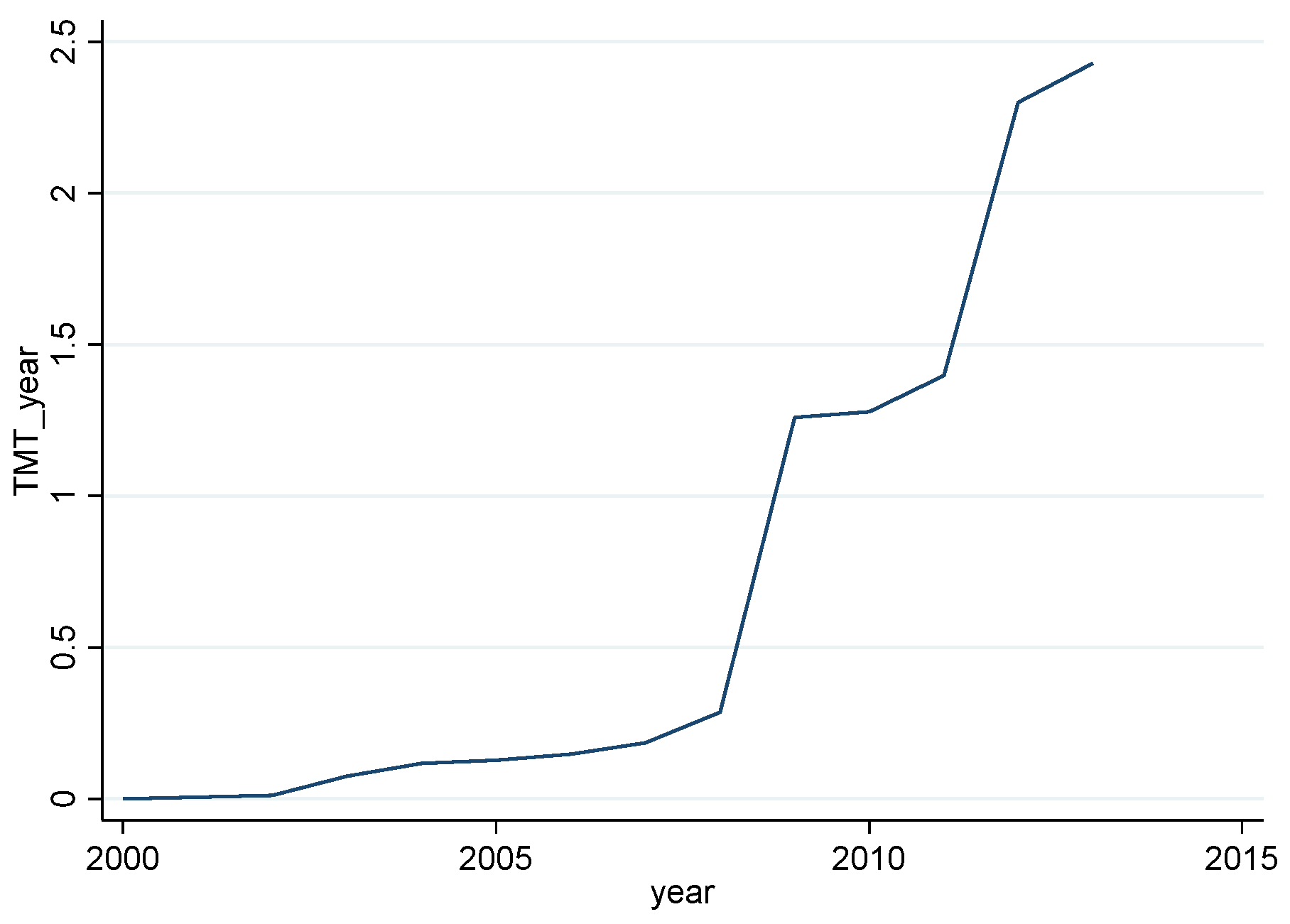

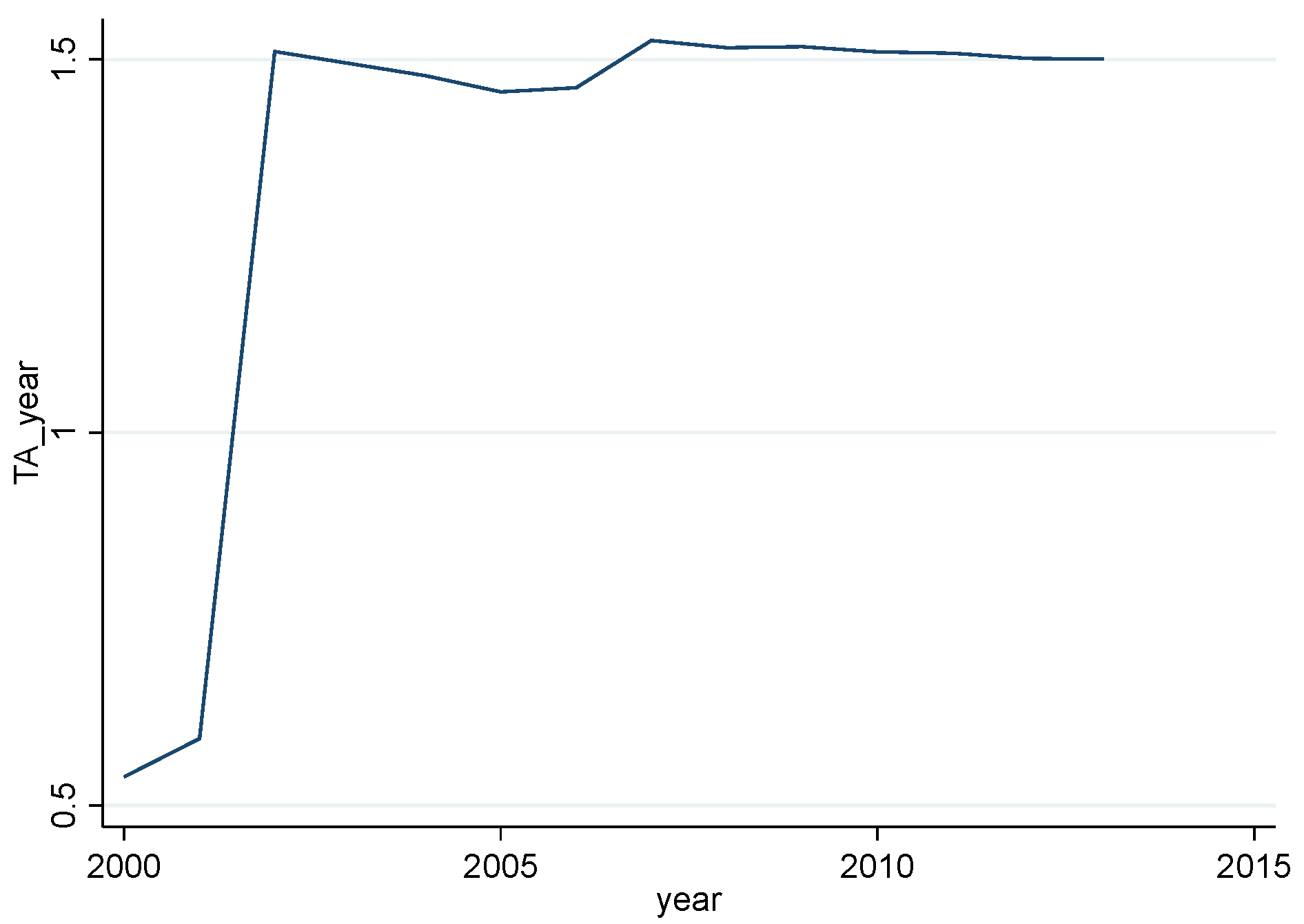

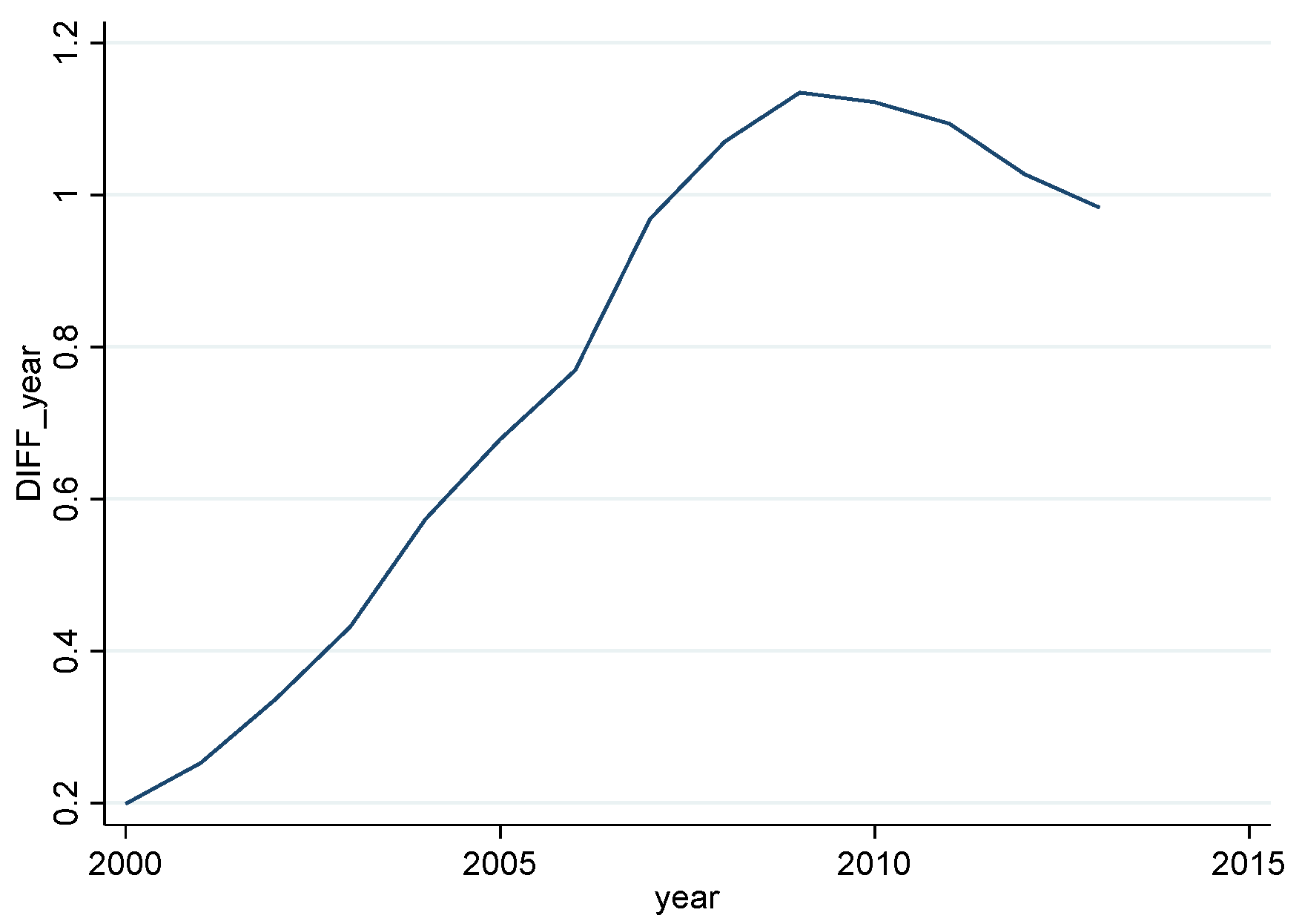

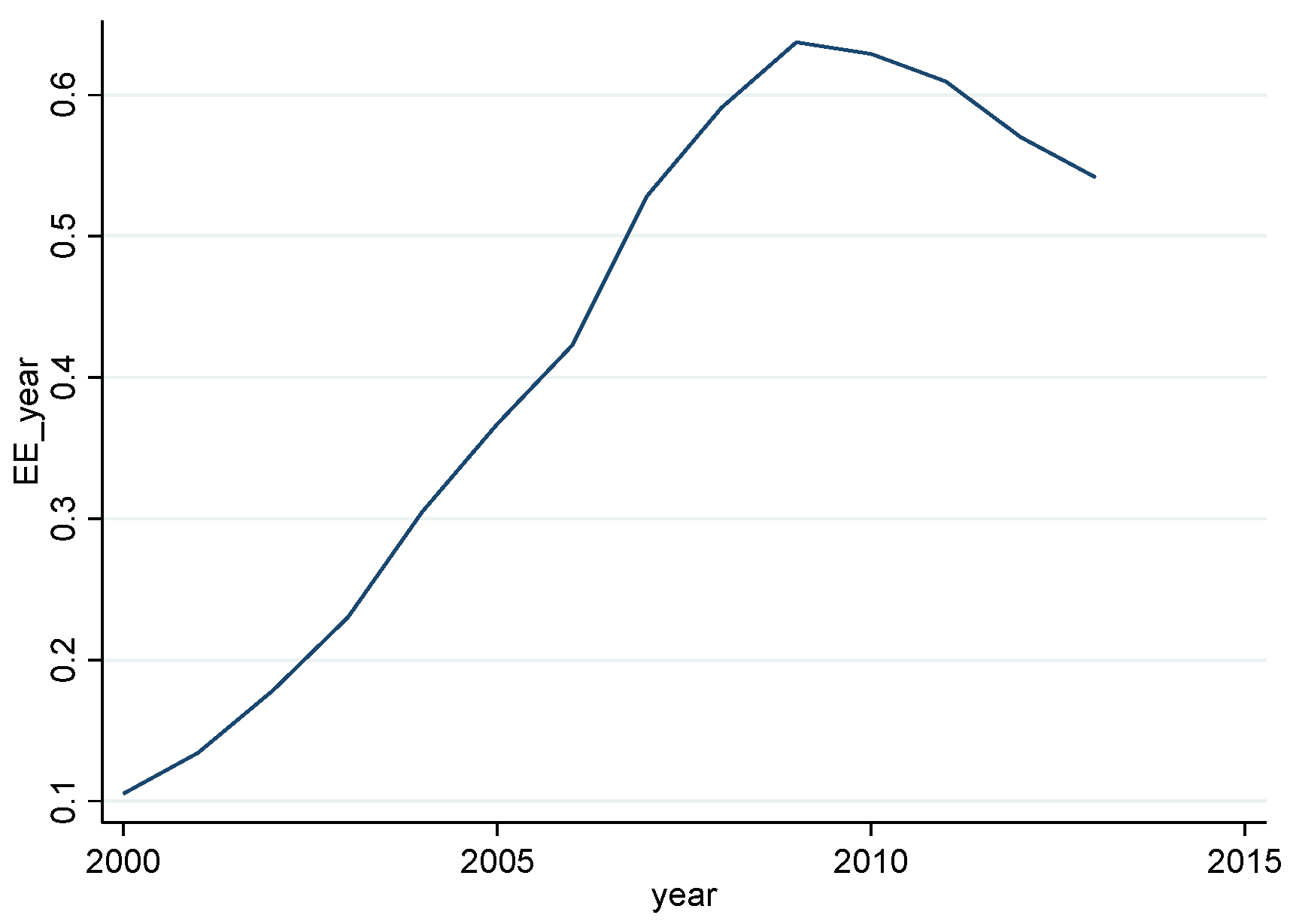

3.2.3. Key Metrics

4. Empirical Analysis Results

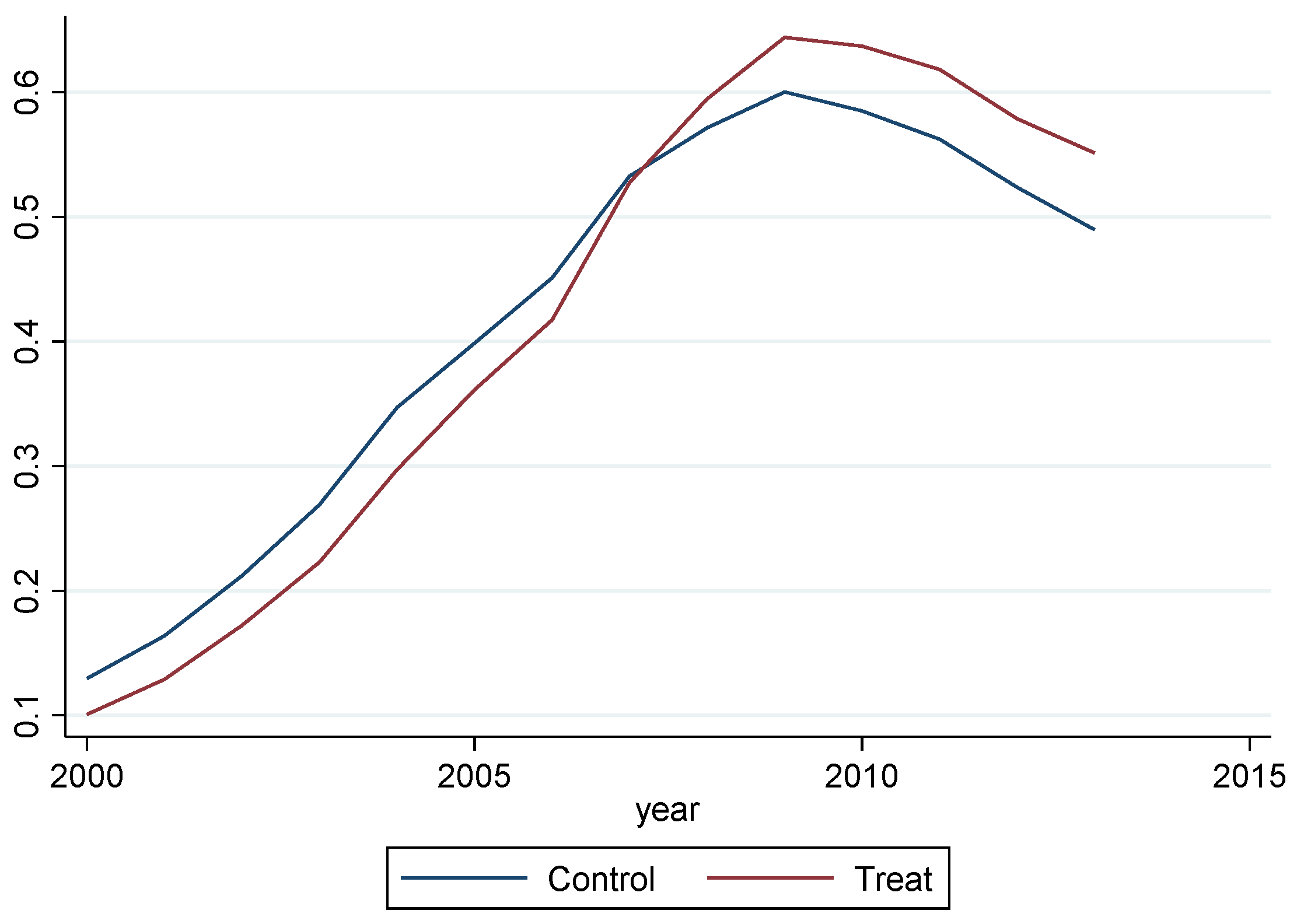

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Benchmark Regression Results

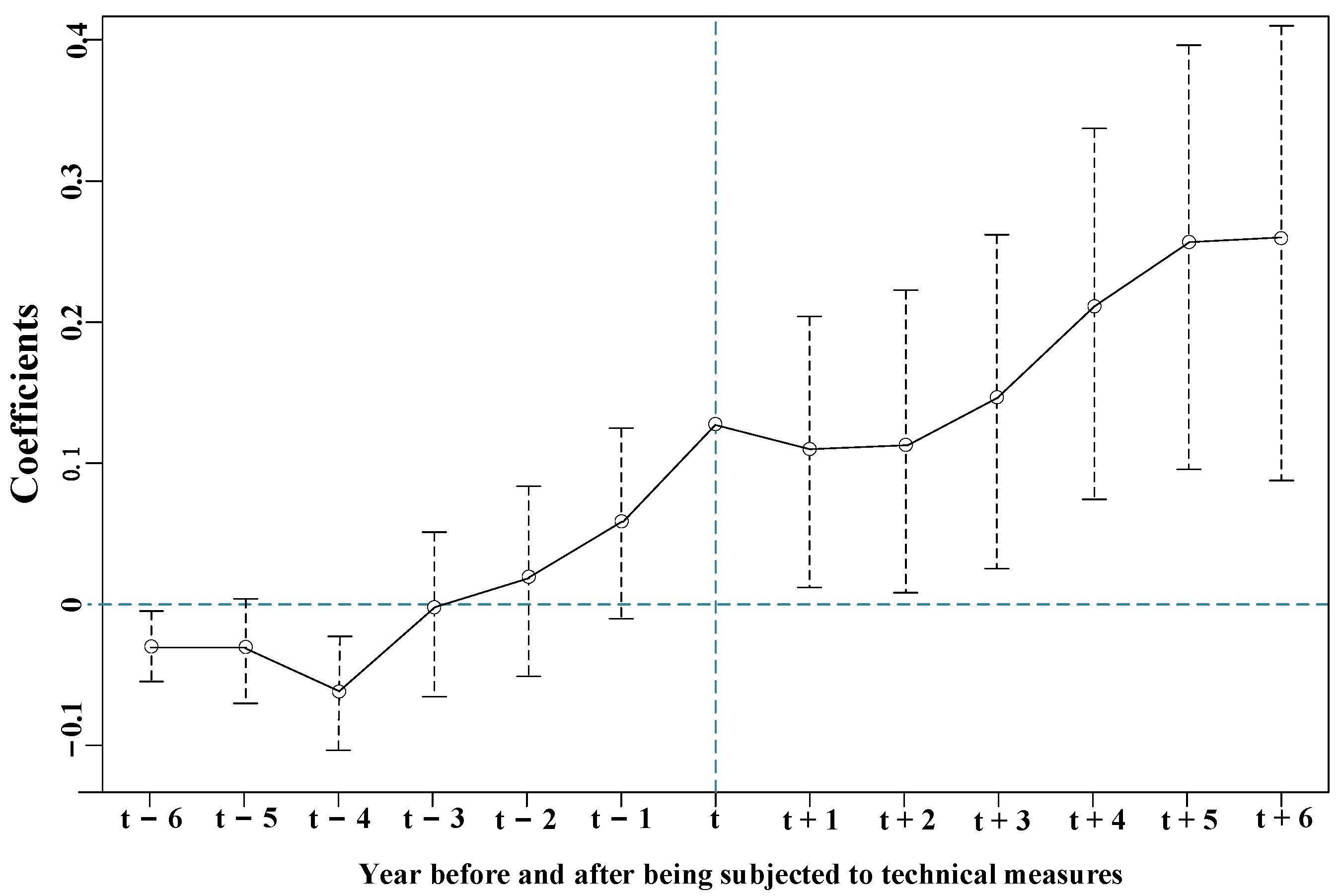

4.3. Parallel Trend Test

4.4. Other Robustness Checks

4.4.1. Control Industry Time Trends

4.4.2. Two-Period DID Method

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis Results

4.6. Mechanism Test Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Melitz, M.J. The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 2003, 71, 1695–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawless, M. Firm export dynamics and the geography of trade. J. Int. Econ. 2009, 77, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaney, T. Distorted gravity: Heterogeneous firms, market structure, and the geography of international trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008, 98, 1707–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altıntaş, M.H.; Tokol, T.; Harcar, T. The effects of export barriers on perceived export performance: An empirical research on SMEs in Turkey. EuroMed J. Bus. 2007, 2, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D.L.; Mengüç, B.; Myers, C.P. Revisiting firm characteristics, strategy, and export performance relationship: A survey of the literature and an investigation of new zealand small manufacturing firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, C.C.; Ahmed, Z.U. The impact of barriers to export on export marketing performance. J. Glob. Mark. 2005, 19, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahiya, E.T.; Ddean, D.L. Export performance: Multiple predictors and multiple measures approach. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2014, 26, 378–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikeas, C.S.; Piercy, N.F.; Ioannidis, C. Determinants of export performance in a European context. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 6–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogiannis, M.; Bourlakis, M.A.; Dawson, P.J.; Ness, M.R. Assessing export performance in the Greek food and beverage industry: An integrated structural equation model approach. Br. Food J. 2008, 110, 638–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, M.H.; Kettaneh, T. Export problems experienced by high-and low-performing manufacturing companies: A comparative study. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2011, 23, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontagné, L.; Orefice, G.; Piermartini, R.; Rocha, N. Product standards and margins of trade: Firm-level evidence. J. Int. Econ. 2015, 97, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fontagné, L.; Orefice, G. Let’s try next door: Technical Barriers to Trade and multi-destination firms. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2018, 101, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, J.; Bao, X.H. The Effect of Product Quality on Trade Pattern and Welfare: A Review on QHFM Literature. Int. Econ. Trade Res. 2015, 31, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, Y.; Zaki, C. How do technical barriers to trade affect exports? Evidence from egyptian firm-level data. J. Econ. Integr. 2018, 33, 659–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandes, A.M.; Ferro, E.; Wilson, J.S. Product standards and firms’ export decisions. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2019, 33, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronerts, M.J.; Tybout, J.R. The decision to export in Colombia: An empirical model of entry with sunk costs. Am. Econ. Rev. 1997, 87, 545–564. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, X.; Qiu, L.D. How do technical barriers to trade influence trade? Rev. Int. Econ. 2012, 20, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, B.; Li, J. China’s Trading Relations with Major Emerging Countries: Analysis Based on Trade Competitiveness and Trade Complementarity. Financ. Trade Econ. 2011, 10, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations: Volume One; Liberty Classics: London, UK, 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo, D. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1821. [Google Scholar]

- Stolper, W.F.; Samuelson, P.A. Protection and real wages. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1941, 9, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jovanovic, B. Selection and the Evolution of Industry. Econ. J. Econ. Soc. 1982, 50, 649–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Miao, S.-Y. Trade Liberalization of Intermediate Inputs and Technology Choice of China’s Manufacturing Enterprises. Econ. Res. J. 2016, 51, 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Svaleryd, H.; Vlachos, J. Financial markets, the pattern of industrial specialization and comparative advantage: Evidence from OECD countries. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2005, 49, 113–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.B.; Jensen, J.B.; Redding, S.J.; Schott, P.K. Firms in international trade. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krugman, P. Scale economies, product differentiation, and the pattern of trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 1980, 70, 950–959. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, A.B.; Jensen, J.B. Why some firms export. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2004, 86, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatotchev, I.; Stephan, J.; Jindra, B. Ownership structure, strategic controls and export intensity of foreign-invested firms in transition economies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 1133–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.-H.; TANG, Y.-H. Ownership Structure, Industrial Characteristics and Export Decisions: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Firms. J. Int. Trade 2013, 11, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, X. The Control Manner of our State-Owned Assets and its Current Situation. Comp. Econ. Soc. Syst. 2003, 3, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Q. Does trade policy uncertainty affect Chinese manufacturing firms’ imports. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 55, 148–164. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Variable | Expected Symbol | Observations | Mean | Standard | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dependent variable | EE | 570,192 | 0.0927 | 0.0929 | 0 | 0.5246 | |

| independent variable | TMT | + | 570,192 | 0.2641 | 0.5846 | 0 | 3.8943 |

| control | TA | + | 570,192 | 0.2934 | 0.3841 | 0 | 4.0518 |

| age | + | 570,192 | 3.0169 | 0.3765 | 0 | 7.6093 | |

| kl | + | 570,192 | 1.6434 | 2.0389 | 0 | 12.4365 | |

| size | + | 570,192 | 6.3126 | 5.5633 | 0 | 19.2672 | |

| own | − | 570,192 | 0.0470 | 0.2117 | 0 | 1 |

| Variable | lnEE | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| lnTMT | 0.0372 *** (0.0013) | 0.0279 *** (0.0011) |

| lnTA | 0.0186 *** (0.0010) | |

| age | 0.7834 *** (0.0109) | |

| kl | 0.0118 *** (0.0005) | |

| size | 0.0156 *** (0.0002) | |

| own | −0.0186 *** (0.0069) | |

| Constant | 0.4513 *** (0.003) | −2.2879 *** (0.0366) |

| Time fixed | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed | Yes | Yes |

| R2_within | 0.3523 | 0.4473 |

| F |

6788.55

(0.0000) | 18,866.51 (0.0000) |

| N | 513,002 | 513,002 |

| Variable | lnEE | |

|---|---|---|

| Control Industry Time Trends | Two-Period Doubling Method | |

| lnTMT | 0.0108 *** (0.0005) | 0.0362 *** (0.0021) |

| Control | Yes | Yes |

| Industry-specific time trend | Yes | No |

| Time fixed | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed | Yes | Yes |

| R2_within | 0.4219 | 0.7526 |

| N | 513,002 | 513,002 |

| Variable | lnEE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMT | TBT | SPS | PSI | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| lnTMT | 0.0279 *** (0.0011) | |||

| lnTBT | 0.0286 *** (0.0011) | |||

| lnSPS | 0.0008 (0.0025) | |||

| lnPSI | 0.078 9 *** (0.0052) | |||

| lnTA | 0.0186 *** (0.001) | 0.0189 *** (0.0010) | 0.0200 *** (0.0010) | 0.0202 *** (0.0010) |

| age | 0.7834 *** (0.010) | 0.7824 *** (0.0109) | 0.7884 *** (0.0109) | 0.7887 *** (0.0109) |

| kl | 0.0118 *** (0.0005) | 0.0118 *** (0.0005) | 0.0119 *** (0.0005) | 0.0119 *** (0.0005) |

| size | 0.0156 *** (0.0002) | 0.0156 *** (0.0002) | 0.0158 *** (0.0002) | 0.0158 *** (0.0002) |

| own | −0.0186 *** (0.0069) | −0.0187 *** (0.0069) | −0.0176 *** (0.0069) | −0.0173 *** (0.0069) |

| Constant | −2.2879 *** (0.0366) | −2.2836 *** (0.0366) | −2.2407 *** (0.0368) | −2.2471 *** (0.0368) |

| Time fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2_within | 0.4473 | 0.4474 | 0.4441 | 0.4450 |

| F | 18,866.51 (0.0000) | 18,988.22 (0.0000) |

18,767.14

(0.0000) | 18,654.11 (0.0000) |

| N | 513,002 | 513,002 | 513,002 | 513,002 |

| Variable | lnEE | lnDIFF | lnEE |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| lnTMT | 0.0279 *** (0.0011) | 0.0789 *** (0.0019) | −0.0012 (0.0007) |

| lnDIFF | 0.3695 *** (0.0019) | ||

| lnTA | 0.0186 *** (0.0010) | 0.0244 *** (0.0024) | 0.0096 *** (0.0008) |

| age | 0.7834 *** (0.0109) | 1.0018 *** (0.0266) | 0.4132 *** (0.0086) |

| kl | 0.0118 *** (0.0005) | 0.0215 *** (0.0013) | 0.0038 *** (0.0004) |

| size | 0.0156 *** (0.0002) | 0.0288 *** (0.0005) | 0.0049 *** (0.0001) |

| own | −0.0186 *** (0.0069) | −0.0193 *** (0.0156) | −0.0115 ** (0.0052) |

| Constant | −2.2879 *** (0.0366) | −2.8190 *** (0.0885) | −1.2463 *** (0.0285) |

| Time fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2_within | 0.4473 | 0.3797 | 0.7548 |

| F | 18,866.51 (0.0000) | 3282.55 (0.0000) | 8384.50 (0.0000) |

| N | 513,002 | 513,002 | 513,002 |

| Variable | lnEE | lnDIFF | lnEE |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| lnTBT | 0.0286 *** (0.0011) | 0.0783 *** (0.0019) | −0.0003 (0.0008) |

| lnDIFF | 0.3694 *** (0.0019) | ||

| lnTA | 0.0189 *** (0.0010) | 0.0254 *** (0.0024) | 0.0096 *** (0.0008) |

| age | 0.7824 *** (0.0109) | 0.9996 *** (0.0266) | 0.4132 *** (0.0086) |

| kl | 0.0118 *** (0.0005) | 0.0216 *** (0.0013) | 0.0038 *** (0.0004) |

| size | 0.0156 *** (0.0002) | 0.0288 *** (0.0005) | 0.0049 *** (0.0001) |

| own | −0.0187 *** (0.0069) | −0.0196 (0.0156) | −0.0115 ** (0.0052) |

| Constant | −2.2836 *** (0.0366) | −2.8033 *** (0.0885) | −1.2482 *** (0.0285) |

| Time fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2_within | 0.4474 | 0.3795 | 0.7548 |

| F | 18,988.22 (0.0000) | 3279.19 (0.0000) | 8385.04 (0.0000) |

| N | 513,002 | 513,002 | 513,002 |

| Variable | lnEE | lnDIFF | lnEE |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| lnPSI | 0.0789 *** (0.0052) | 0.2142 *** (0.0123) | −0.0002 (0.0042) |

| lnDIFF | 0.3693 *** (0.0019) | ||

| lnTA | 0.0202 *** (0.0010) | 0.0288 *** (0.0024) | 0.0096 *** (0.0008) |

| age | 0.7887 *** (0.0109) | 1.0168 *** (0.0269) | 0.4131 *** (0.0086) |

| kl | 0.0119 *** (0.0005) | 0.0218 *** (0.0013) | 0.0038 *** (0.0004) |

| size | 0.0158 *** (0.0002) | 0.0292 *** (0.0005) | 0.0049 *** (0.0001) |

| own | −0.0173 ** (0.0069) | −0.0155 (0.0157) | −0.0115 ** (0.0052) |

| C | −2.2471 *** (0.0368) | −2.7031 *** (0.0897) | −1.2489 *** (0.0284) |

| Time fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2_within | 0.4450 | 0.3745 | 0.7548 |

| F | 18,654.11 (0.0000) | 3208.04 (0.0000) | 8370.96 (0.0000) |

| N | 513,002 | 513,002 | 513,002 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.-L.; Zhao, W.-W. Research on the Impact of Technical Measures on Enterprise Export Participation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148909

Wang H-L, Zhao W-W. Research on the Impact of Technical Measures on Enterprise Export Participation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148909

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Han-Lin, and Wan-Wan Zhao. 2022. "Research on the Impact of Technical Measures on Enterprise Export Participation" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148909