Institutions Rule in Export Diversity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

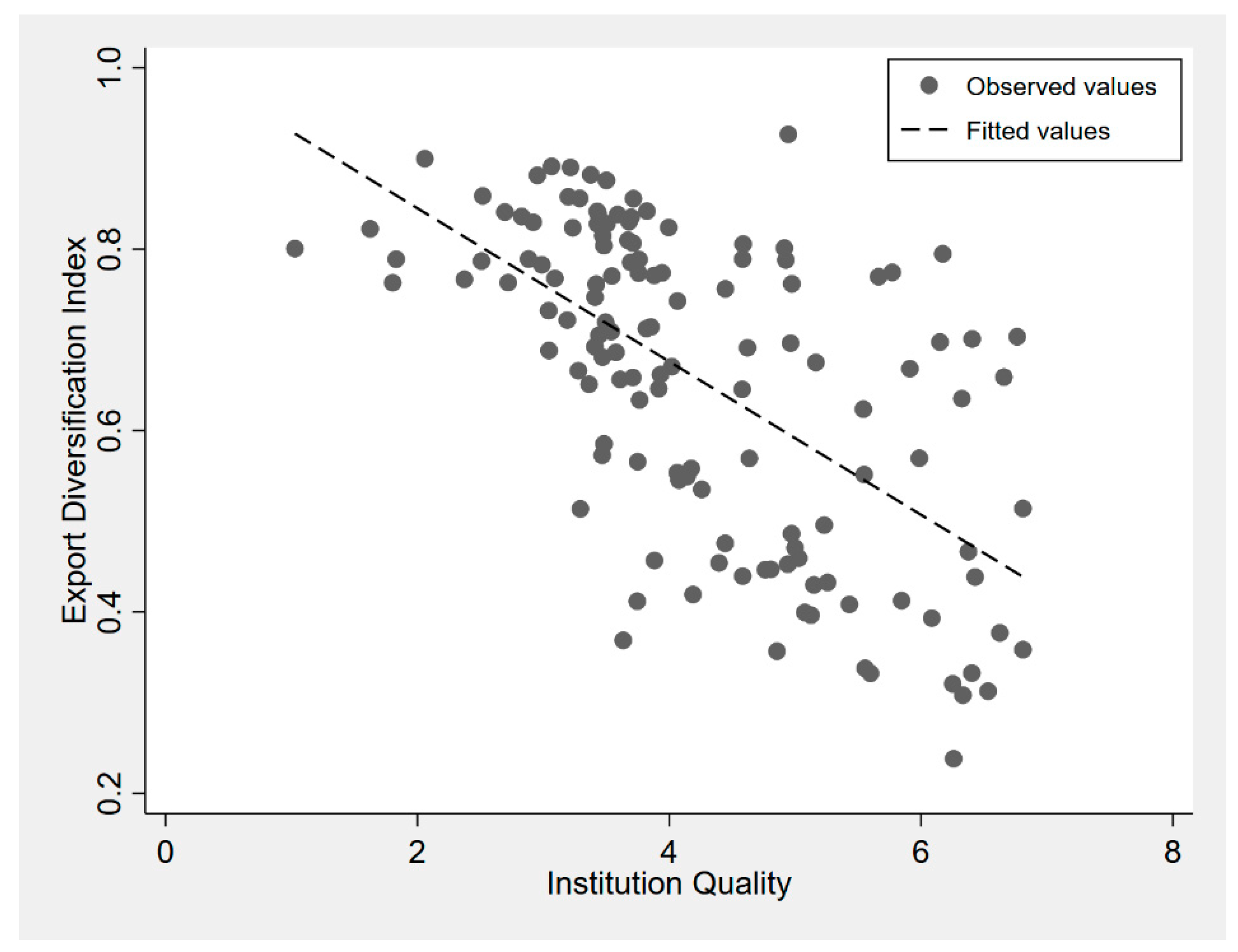

3.1. OLS Estimation

3.2. Variables and Data Sources

3.2.1. Export Diversity

3.2.2. Institutional Quality

3.2.3. Others

4. Results

5. Robustness Check

5.1. Alternative Measures

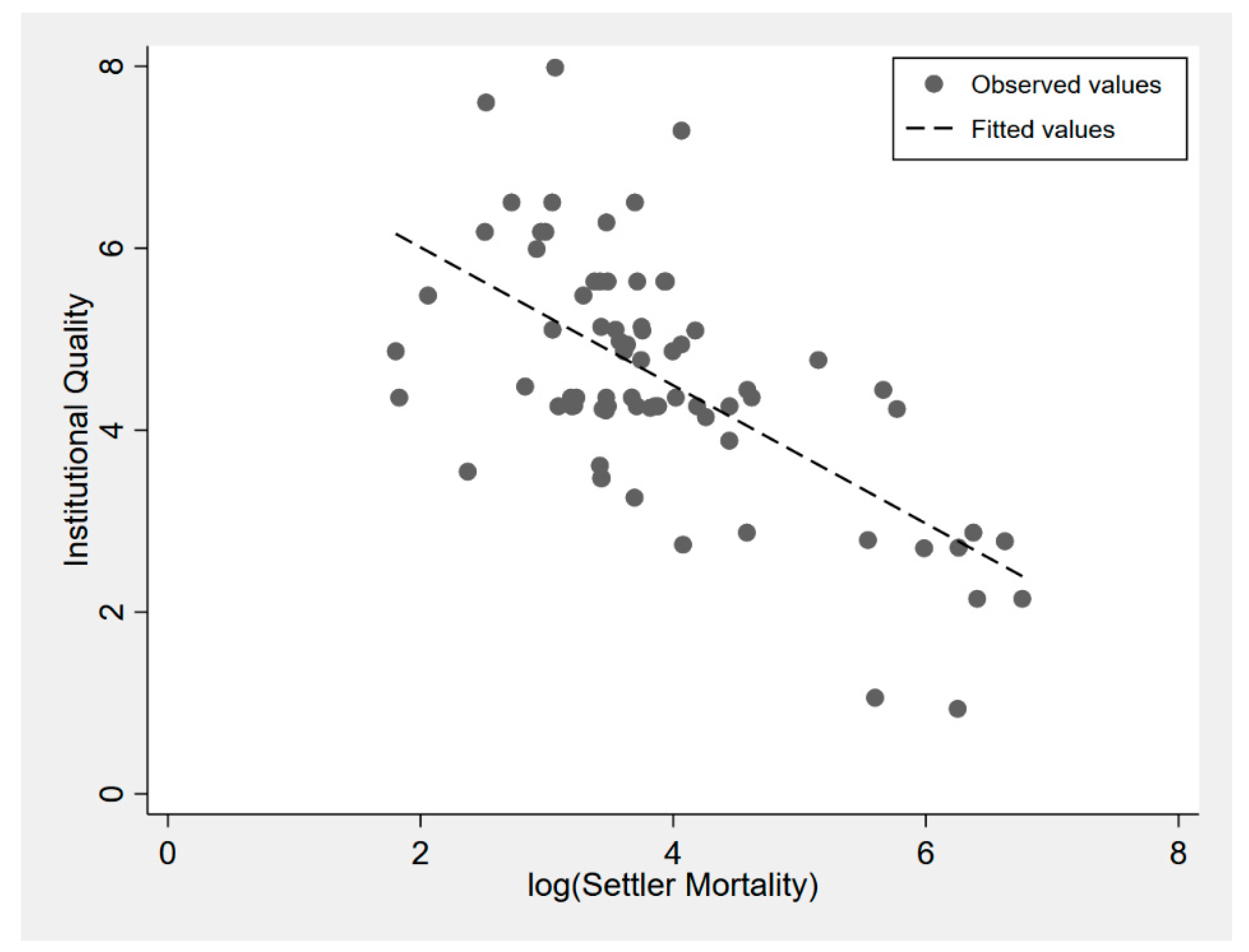

5.2. Instrumental Variable Estimation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Imbs, J.; Wacziarg, R. Stages of Diversification. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, B.; Lederman, D. Diversification, Innovation, and Imitation Inside the Global Technological Frontier; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cadot, O.; Carrère, C.; Strauss-Kahn, V. Export Diversification: What’s behind the Hump? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2011, 93, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D.; Subramanian, A.; Trebbi, F. Institutions Rule: The Primacy of Institutions over Geography and Integration in Economic Development. J. Econ. Growth 2004, 9, 131–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 1369–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, P.R. Intraindustry Specialization and the Gains from Trade. J. Polit. Econ. 1981, 89, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Zilibotti, F. Was Prometheus Unbound by Chance? Risk, Diversification, and Growth. J. Polit. Econ. 1997, 105, 709–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, M.; Tenreyro, S. Volatility and Development. Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 243–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedictis, L.; Gallegati, M.; Tamberi, M. Overall Trade Specialization and Economic Development: Countries Diversify. Rev. World Econ. 2009, 145, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parteka, A. Employment and Export Specialisation along the Development Path: Some Robust Evidence. Rev. World Econ. 2010, 145, 615–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parteka, A.; Tamberi, M. What Determines Export Diversification in the Development Process? Empirical Assessment. World Econ. 2013, 36, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mau, K. Export Diversification and Income Differences Reconsidered: The Extensive Product Margin in Theory and Application. Rev. World Econ. 2016, 152, 351–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, R.; Parteka, A.; Pittiglio, R. Export Diversification and Economic Development: A Dynamic Spatial Data Analysis. Rev. Int. Econ. 2018, 26, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, A.; Parteka, A. Relative Productivity, Country Size and Export Diversification. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2021, 57, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Van Oort, F.; Verburg, T. Related Variety, Unrelated Variety and Regional Economic Growth. Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviotti, P.P.; Frenken, K. Export Variety and the Economic Performance of Countries. J. Evol. Econ. 2008, 18, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Ljungqvist, L.; Howitt, P.; Howitt, P.W.; Brant-Collett, M.; García-Peñalosa, C. Endogenous Growth Theory; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; ISBN 0-262-01166-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R.E. On the Mechanics of Economic Development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosin, M.R.; Alvarez, R.; Bravo-Ortega, C. Determinants of Export Diversification Around the World: 1962–2000. World Econ. 2012, 35, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhiraika, A.B.; Mbate, M.M. Assessing the Determinants of Export Diversification in Africa. Appl. Econom. Int. Dev. 2014, 14, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jetter, M.; Ramírez Hassan, A. Want Export Diversification? Educate the Kids First. Econ. Inq. 2015, 53, 1765–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthélemy, J.-C. International trade and economic diversification. Rev. Econ. Polit. 2005, 115, 591–611. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, F.B. Export Diversification in East Asian Economies: Some Factors Affecting the Scenario. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2011, 1, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadot, O.; Carrère, C.; Strauss-Kahn, V. Trade Diversification, Income, and Growth: What Do We Know? J. Econ. Surv. 2013, 27, 790–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regolo, J. Export Diversification: How Much Does the Choice of the Trading Partner Matter? J. Int. Econ. 2013, 91, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, P.; Mihov, I.; Van Zandt, T. Trade Diversification and Economic Development. Mimeogr. INSEAD. 2008. Available online: https://www.insead.edu/sites/default/files/assets/faculty-personal-site/pushan-dutt/documents/diversification.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Carrère, C.; Cadot, O.; Strauss-Kahn, V. Trade Diversification: Drivers and Impacts. In Trade and Employment: From Myths to Facts; ILO-EC International Labour Office, European Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 253–307. [Google Scholar]

- Omgba, L.D. Institutional Foundations of Export Diversification Patterns in Oil-Producing Countries. J. Comp. Econ. 2014, 42, 1052–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Yang, D.T. Expanding Export Variety: The Role of Institutional Reforms in Developing Countries. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 118, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin Gutiérrez de Piñeres, S.; Ferrantino, M. Export Diversification and Structural Dynamics in the Growth Process: The Case of Chile. J. Dev. Econ. 1997, 52, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hammouda, H.; Karingi, S.; Njuguna, A.; Sadni Jallab, M. Diversification: Towards A New Paradigm for Africa’s Development; MPRA Paper; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T.A.-D.; Phi, M.H.; Diaw, D. Export Diversification and Real Exchange Rate in Emerging Latin America and Asia: A South–North vs. South-South Decomposition. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2017, 26, 649–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebczuk, R.N.; Berrettoni, D. Explaining Export Diversification: An Empirical Analysis; Department of Economics, Working Papers; Departamento de Economía, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Starosta de Waldemar, F. How Costly Is Rent-Seeking to Diversification: An Empirical Approach. 2010. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/39991/1/253_starosta.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Cadot, O.; de Melo, J.; Plane, P.; Wagner, L.; Woldemichael, M.T. Industrialisation et Transformation Structurelle: L’Afrique Sub-Saharienne Peut-Elle Se Développer sans Usines? Papiers de Recherche. 2015, pp. 1–85. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/feuilleter.php?ID_ARTICLE=AFD_VERGN_2015_02_0001 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Levchenko, A.A. Institutional Quality and International Trade. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2007, 74, 791–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desroches, B.; Francis, M. Institutional Quality, Trade, and the Changing Distribution of World Income; Bank of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006.

- Francois, J.; Manchin, M. Institutional Quality, Infrastructure, and the Propensity to Export. Citeseer. 2006. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.557.5080&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Anderson, J.E.; Marcouiller, D. Insecurity and the Pattern of Trade: An Empirical Investigation. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2002, 84, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, H.L.; Linders, G.-J.; Rietveld, P.; Subramanian, U. The Institutional Determinants of Bilateral Trade Patterns. Kyklos 2004, 57, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Antràs, P.; Helpman, E. Contracts and Technology Adoption. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 916–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costinot, A. On the Origins of Comparative Advantage. J. Int. Econ. 2009, 77, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P.; Lee, J.Y. Contract Enforcement and International Trade. Econ. Polit. 2007, 19, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, N. Relationship-Specificity, Incomplete Contracts, and the Pattern of Trade. Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 569–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, D.; Moenius, J.; Pistor, K. Trade, Law, and Product Complexity. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2006, 88, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, T. Institutions as a Source of Comparative Advantage; Fukushima University Working Paper; Fukushima University: Fukushima, Japan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, S.; Wang, X.; Wu, J. Does Institutional Quality Matter for Export Product Quality? Evidence from China. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2021, 30, 1077–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Warner, A.M. The Curse of Natural Resources. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Warner, A. Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Auty, R. Sustaining Development in Mineral Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 0-203-42259-7. [Google Scholar]

- Auty, R.M. Resource Abundance and Economic Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; ISBN 0-19-924688-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gylfason, T. Natural Resources, Education, and Economic Development. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunnschweiler, C.N.; Bulte, E.H. The Resource Curse Revisited and Revised: A Tale of Paradoxes and Red Herrings. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2008, 55, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeev, M.; Conrad, R. The Elusive Curse of Oil. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2009, 91, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, J.A. The Natural Resource Curse: A Survey of Diagnoses and Some Prescriptions; Commodity Price Volatility and Inclusive Growth in Low-Income Countries; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Badeeb, R.A.; Lean, H.H.; Clark, J. The Evolution of the Natural Resource Curse Thesis: A Critical Literature Survey. Resour. Policy 2017, 51, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaglia, F.; Fukasaku, K. Export Diversification in Low-Income Countries: An International Challenge after Doha; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lederman, D.; Maloney, W.F. Natural Resources: Neither Curse nor Destiny; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Herzer, D.; Nowak-Lehnmann D., F. What Does Export Diversification Do for Growth? An Econometric Analysis. Appl. Econ. 2006, 38, 1825–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddatz, C. Are External Shocks Responsible for the Instability of Output in Low-Income Countries? J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 84, 155–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, E.A.; De Gregorio, J.; Loayza, N.V. Output Volatility and Openness to Trade: A Reassessment [with Comments]. Economía 2008, 9, 105–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosin, M.R. Export Diversification and Growth in Emerging Economies; Working Paper; Department of Economics, University of Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, H. Export Diversification and Economic Growth. In Breaking into New Markets: Emerging Lessons for Export Diversification; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, C.-H.; Lee, H. Trade Structure, FTAs, and Economic Growth. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2010, 14, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kali, R.; Méndez, F.; Reyes, J. Trade Structure and Economic Growth. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2007, 16, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coniglio, N.D.; Vurchio, D.; Cantore, N.; Clara, M. On the Evolution of Comparative Advantage: Path-Dependent versus Path-Defying Changes. J. Int. Econ. 2021, 133, 103522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lectard, P.; Rougier, E. Can Developing Countries Gain from Defying Comparative Advantage? Distance to Comparative Advantage, Export Diversification and Sophistication, and the Dynamics of Specialization. World Dev. 2018, 102, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, D.; Rosenow, S.; Stein, E.; Wagner, R. Export Take-Offs and Acceleration: Unpacking Cross-Sector Linkages in the Evolution of Comparative Advantage. World Dev. 2019, 117, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, A.; Acharyya, R. Export Diversification, Composition, and Economic Growth: Evidence from Cross-Country Analysis. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2013, 22, 959–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, R.; Kee, H.L. Export Variety and Country Productivity: Estimating the Monopolistic Competition Model with Endogenous Productivity. J. Int. Econ. 2008, 74, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrieri, P.; Iammarino, S. Dynamics of Export Specialization in the Regions of the Italian Mezzogiorno: Persistence and Change. Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 933–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramcharan, R. Does Economic Diversification Lead to Financial Development? Evidence From Topography; IMF Working Paper; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Name | Definition | Data Source | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ediv | Export diversification index | the UNCTAD STAT database | 133 | 0.656 | 0.172 | 0.238 | 0.927 |

| ecie | Export concentration index | the UNCTAD STAT database | 133 | 0.316 | 0.214 | 0.053 | 0.981 |

| enpe | Number of products exported | the UNCTAD STAT database | 133 | 196.489 | 59.753 | 10 | 260 |

| iq | Average of four normalized variables (investment profile, corruption, law and order, and bureaucratic quality) | ICRG database | 133 | 4.241 | 1.241 | 1.027 | 6.809 |

| corruption | Corruption Index | ICRG database | 133 | 2.585 | 1.122 | 0.419 | 5.823 |

| g_rl | Rule of Law Index | WGI database | 133 | −0.009 | 1.027 | −2.323 | 1.988 |

| lat_abst | Latitude of capital scaled between 0 and 1 | Acemoglu et al. (2001) [5] | 130 | 0.300 | 0.197 | 0.000 | 0.722 |

| population_density | People per sq. km of land area | WDI database | 133 | 230.833 | 849.652 | 1.757 | 7031.250 |

| trade | Trade as a share of GDP | WDI database | 132 | 67.733 | 42.801 | 20.179 | 343.512 |

| lgdp_pc | log PPP GDP per capita | WDI database | 130 | 9.383 | 1.186 | 6.784 | 11.443 |

| resource | Natural resource endowments dummy | Auty (2001) [50] | 71 | 0.775 | 0.421 | 0 | 1 |

| africa | Africa dummy | Acemoglu et al. (2001) [5] | 130 | 0.285 | 0.453 | 0 | 1 |

| asia | Asia dummy | Acemoglu et al. (2001) [5] | 130 | 0.246 | 0.432 | 0 | 1 |

| other | Other continental dummy (excluding America) | Acemoglu et al. (2001) [5] | 130 | 0.023 | 0.151 | 0 | 1 |

| logem4 | log European settler mortality | Acemoglu et al. (2001) [5] | 74 | 4.567 | 1.342 | 0.936 | 7.986 |

| Variables | ediv | ecie | enpe | iq | Corruption | g_rl | lat_abst | Population_Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ediv | 1.000 | |||||||

| ecie | 0.733 * | 1.000 | ||||||

| enpe | −0.697 * | −0.642 * | 1.000 | |||||

| iq | −0.610 * | −0.429 * | 0.570 * | 1.000 | ||||

| corruption | −0.511 * | −0.369 * | 0.444 * | 0.901 * | 1.000 | |||

| g_rl | −0.618 * | −0.453 * | 0.560 * | 0.962 * | 0.907 * | 1.000 | ||

| lat_abst | −0.556 * | −0.396 * | 0.471 * | 0.612 * | 0.537 * | 0.610 * | 1.000 | |

| population_density | −0.128 | −0.063 | 0.136 | 0.222 * | 0.201 * | 0.227 * | −0.095 | 1.000 |

| trade | −0.252 * | −0.104 | 0.225 * | 0.282 * | 0.188 * | 0.292 * | 0.105 | 0.700 * |

| lgdp_pc | −0.589 * | −0.319 * | 0.628 * | 0.803 * | 0.650 * | 0.778 * | 0.624 * | 0.201 * |

| resource | 0.381 * | 0.272 * | −0.252 * | −0.105 | −0.189 | −0.135 | −0.028 | −0.372 * |

| africa | 0.470 * | 0.388 * | −0.527 * | −0.444 * | −0.360 * | −0.438 * | −0.468 * | −0.128 |

| asia | −0.018 | 0.046 | 0.151 * | −0.002 | −0.118 | −0.043 | −0.070 | 0.278 * |

| other | 0.018 | −0.042 | 0.064 | 0.248 * | 0.264 * | 0.253 * | 0.065 | 0.038 |

| logem4 | 0.543 * | 0.426 * | −0.469 * | −0.633 * | −0.582 * | −0.632 * | −0.535 * | −0.244 * |

| Variables | trade | lgdp_pc | resource_abundence | africa | asia | other | logem4 | |

| ediv | ||||||||

| ecie | ||||||||

| enpe | ||||||||

| iq | ||||||||

| corruption | ||||||||

| g_rl | ||||||||

| lat_abst | ||||||||

| population_density | ||||||||

| trade | 1.000 | |||||||

| lgdp_pc | 0.344 * | 1.000 | ||||||

| resource | −0.211 * | −0.111 | 1.000 | |||||

| africa | −0.230 * | −0.688 * | 0.218 * | 1.000 | ||||

| asia | 0.206 * | 0.129 | −0.408 * | −0.360 * | 1.000 | |||

| other | −0.041 | 0.155 * | - 1 | −0.097 | −0.088 | 1.000 | ||

| logem4 | −0.217 * | −0.696 * | 0.197 | 0.587 * | −0.162 | −0.340 * | 1.000 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | Base Sample | Full Sample | Base Sample | Full Sample | Base Sample | Full Sample | Base Sample | Full Sample | Base Sample | |

| iq | −0.0845 *** | −0.0732 *** | −0.0614 *** | −0.0693 *** | −0.0514 *** | −0.0722 *** | −0.0619 *** | −0.0712 *** | −0.0468 *** | −0.0420 * |

| (−8.5717) | (−4.2632) | (−5.1648) | (−3.9296) | (−3.7511) | (−4.0207) | (−5.2454) | (−3.4265) | (−2.8446) | (−1.6862) | |

| lat_abst | −0.2520 *** | −0.0615 | −0.1205 | −0.0283 | −0.1628 ** | −0.1249 | −0.2183 ** | −0.0568 | ||

| (−3.3830) | (−0.4814) | (−0.9988) | (−0.1988) | (−2.0443) | (−1.0052) | (−2.4827) | (−0.4367) | |||

| resource | 0.1093 *** | 0.0658 * | ||||||||

| (3.5979) | (1.9417) | |||||||||

| africa | 0.0868 *** | 0.0351 | ||||||||

| (3.0978) | (1.2221) | |||||||||

| asia | 0.0259 | −0.0618 | ||||||||

| (0.8286) | (−1.1106) | |||||||||

| other | 0.1937 *** | 0.1690 ** | ||||||||

| (3.7583) | (2.1441) | |||||||||

| population _density | 3.97 × 10−6 | 5.87 × 10−7 | ||||||||

| (0.2190) | (0.0221) | |||||||||

| trade | −0.0004 | −0.0001 | ||||||||

| (−0.8931) | (−0.1657) | |||||||||

| lgdp_pc | −0.0226 | −0.0367 ** | ||||||||

| (−1.4148) | (−2.0690) | |||||||||

| _cons | 1.0142 *** | 0.9982 *** | 0.9911 *** | 0.9940 *** | 0.8487 *** | 0.9438 *** | 0.9306 *** | 0.9990 *** | 1.1563 *** | 1.2213 *** |

| (26.2851) | (16.2974) | (25.7031) | (16.4790) | (15.0963) | (12.1648) | (20.5357) | (14.6228) | (10.9721) | (9.1830) | |

| N | 133 | 64 | 130 | 64 | 71 | 54 | 130 | 64 | 126 | 63 |

| r2 | 0.373 | 0.329 | 0.430 | 0.331 | 0.299 | 0.339 | 0.484 | 0.440 | 0.443 | 0.372 |

| Mean VIF | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.55 | 1.36 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.52 | 1.43 | 2.32 | 2.59 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ediv | ecie | enpe | ||||||

| Full Sample | Base Sample | Full Sample | Base Sample | Full Sample | Base Sample | Full Sample | Base Sample | |

| iq | −0.0480 *** | −0.0584 *** | 20.1571 *** | 15.9053 * | ||||

| (−2.9527) | (−2.6944) | (4.7484) | (1.9976) | |||||

| corruption | −0.0483 *** | −0.0524 ** | ||||||

| (−3.4152) | (−2.1128) | |||||||

| g_rl | −0.0767 *** | −0.0882 *** | ||||||

| (−5.3491) | (−3.3998) | |||||||

| lat_abst | −0.2437 *** | −0.2183 | −0.1626 ** | −0.1302 | −0.0965 | −0.2137 | 26.6173 | 31.6559 |

| (−3.1692) | (−1.5290) | (−2.1074) | (−1.0853) | (−0.8715) | (−1.4110) | (0.8642) | (0.6845) | |

| africa | 0.0972 *** | 0.0402 | 0.0827 *** | 0.0337 | 0.1359 ** | 0.0556 | −38.7019 *** | −24.0556 |

| (3.3176) | (1.3271) | (2.9243) | (1.1809) | (2.4359) | (1.1285) | (−2.7862) | (−1.5759) | |

| asia | 0.0120 | −0.0818 | 0.0168 | −0.0617 | 0.0744 | −0.0636 | 6.5071 | 37.4244 *** |

| (0.3705) | (−1.3085) | (0.5476) | (−1.0908) | (1.6507) | (−1.3518) | (0.6255) | (2.8809) | |

| other | 0.1682 *** | 0.1294 | 0.1963 *** | 0.1780 ** | 0.1045 *** | 0.1292 ** | −27.8062 * | −14.6158 |

| (2.8886) | (1.5214) | (4.4076) | (2.3455) | (2.7852) | (2.4964) | (−1.8395) | (−0.6198) | |

| _cons | 0.8188 *** | 0.8664 *** | 0.6712 *** | 0.6965 *** | 0.4900 *** | 0.5754 *** | 113.5455 *** | 124.9430 *** |

| (19.3665) | (15.9913) | (20.5949) | (18.9718) | (6.5070) | (6.6845) | (5.7757) | (4.2314) | |

| N | 130 | 64 | 130 | 64 | 130 | 64 | 130 | 64 |

| r2 | 0.436 | 0.340 | 0.490 | 0.438 | 0.271 | 0.273 | 0.439 | 0.339 |

| Mean VIF | 1.43 | 1.38 | 1.53 | 1.45 | 1.52 | 1.43 | 1.52 | 1.43 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQ | Corruption | Rule of Law | |||||||

| Panel A: Two-Stage Least Squares | |||||||||

| iq | −0.1216 *** | −0.1274 ** | −0.1447 *** | ||||||

| (−5.4752) | (−2.5388) | (−2.8729) | |||||||

| corruption | −0.1540 *** | −0.2301 * | −0.2138 ** | ||||||

| (−4.6956) | (−1.7882) | (−2.2098) | |||||||

| g_rl | −0.1477 *** | −0.1792 ** | −0.1882 *** | ||||||

| (−5.5523) | (−2.3928) | (−2.8412) | |||||||

| lat_abst | −0.0552 | −0.0207 | −0.0597 | 0.0680 | −0.0196 | 0.0095 | |||

| (−0.3355) | (−0.1002) | (−0.2572) | (0.2239) | (−0.1068) | (0.0436) | ||||

| resource | 0.0657 | 0.0200 | 0.0478 | ||||||

| (1.5512) | (0.2657) | (0.9779) | |||||||

| africa | −0.0032 | −0.0256 | −0.0146 | ||||||

| (−0.0805) | (−0.4432) | (−0.3436) | |||||||

| asia | −0.0732 * | −0.1038 * | −0.0705 | ||||||

| (−1.7277) | (−1.9319) | (−1.6385) | |||||||

| other | 0.3214 *** | 0.4060 ** | 0.3427 *** | ||||||

| (2.8452) | (2.3010) | (2.8621) | |||||||

| _cons | 1.1687 *** | 1.1397 *** | 1.2649 *** | 1.0636 *** | 1.2115 *** | 1.2071 *** | 0.6543 *** | 0.6025 *** | 0.6466 *** |

| (13.2797) | (6.0317) | (7.4825) | (13.1823) | (3.9386) | (6.2151) | (38.4224) | (11.6553) | (10.5899) | |

| N | 74 | 60 | 74 | 74 | 60 | 74 | 74 | 60 | 74 |

| Panel B: First Stage for Institutional Quality | |||||||||

| logem4 | −0.5282 *** | −0.2861 *** | −0.3131 *** | −0.4171 *** | −0.1584 * | −0.2119 ** | −0.4347 *** | −0.2034 ** | −0.2407 *** |

| (−6.6285) | (−2.9790) | (−3.0081) | (−5.2940) | (−1.9888) | (−2.1932) | (−6.2813) | (−2.5049) | (−2.7183) | |

| lat_abst | 1.2666 | 2.4443 *** | 0.6816 | 2.0691 ** | 1.0991 | 2.0395 *** | |||

| (1.2798) | (2.7393) | (0.7692) | (2.5058) | (1.3006) | (2.8327) | ||||

| resource | −0.2486 | −0.3359 | −0.2766 | ||||||

| (−0.8220) | (−1.4055) | (−1.1804) | |||||||

| asia | 0.1838 | −0.0190 | 0.1553 | ||||||

| (0.5555) | (−0.0695) | (0.5584) | |||||||

| africa | −0.0080 | −0.1100 | −0.0668 | ||||||

| (−0.0331) | (−0.5041) | (−0.3568) | |||||||

| other | 1.2612 *** | 1.2492 ** | 1.0827 *** | ||||||

| (3.8562) | (2.4882) | (5.4374) | |||||||

| _cons | 6.3134 *** | 5.0380 *** | 4.7783 *** | 4.3019 *** | 3.1010 *** | 2.9632 *** | 1.7131 *** | 0.5833 | 0.3877 |

| (15.5089) | (7.4862) | (8.5687) | (10.7795) | (5.3341) | (5.8153) | (5.0132) | (1.0480) | (0.8107) | |

| r2 | 0.401 | 0.241 | 0.526 | 0.339 | 0.160 | 0.483 | 0.399 | 0.224 | 0.531 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lei, W.; Luo, Y. Institutions Rule in Export Diversity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811594

Lei W, Luo Y. Institutions Rule in Export Diversity. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811594

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Wenni, and Yuwei Luo. 2022. "Institutions Rule in Export Diversity" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811594

APA StyleLei, W., & Luo, Y. (2022). Institutions Rule in Export Diversity. Sustainability, 14(18), 11594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811594