Abstract

Entrepreneurship education is a critical issue for higher education (HE) students, and thus has been on the agenda of national sustainable development in China. However, few studies have approached the enhancement of HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies in relation to the perspective of their learning environment. This study developed and employed the Theoretical Model of Entrepreneurial Competencies to examine the path of improving HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies. The results reveal that a diverse learning environment is an important external factor in developing HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies. Knowledge transfer, self-efficacy, and cognitive flexibility mediate this relationship. Moreover, entrepreneurship education significantly moderates the effects of self-efficacy on HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies, but it does not play a moderating role between cognitive flexibility and entrepreneurial competencies. This study provides insights for both policy and managerial endeavors in sustainably advancing HE students’ entrepreneurship through an innovative learning environment.

1. Introduction

Enhancing higher education (HE) students’ entrepreneurial competencies and increasing the success rate of entrepreneurial projects can provide a crucial engine for nationwide innovation [1] and entrepreneurship [2]. It also plays an irreplaceable role in accelerating economic change and sustainable development [1,3,4]. In particular, given China’s large economy and population, HE students are the driving force of innovation and entrepreneurship. Improving their entrepreneurial competencies can help speed up their entrepreneurial actions and alleviate the heavy pressure of unemployment on them, thereby converting high-quality human resources into human capital [5]. As increasing the success rate of entrepreneurial projects and enhancing HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies are key objectives of talent cultivation and higher education reform, researching in this topic to inform academic workforce and policymakers is important for the sustainable development of higher education.

Given that a diverse learning environment is a strong predictor of HE students’ entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors, exploring how to enhance HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies through a diverse learning environment is crucial for the cultivation of innovative talents in colleges and universities. This includes lecturers’ diversified pedagogical approaches, the application of advanced knowledge generated through research into students’ practical experiences, and higher education’s collaboration with external parties (e.g., business organizations). Research indicates that a diverse learning environment in higher education improves learning performance, fosters diverse and innovative thinking, and helps to enrich individuals’ entrepreneurial knowledge base [6] while increasing their entrepreneurial competencies. Yet, despite the acknowledgment of the importance of a diverse learning environment, the existing research focuses on its impact on students’ creativity, cultural intelligence, and critical thinking from an educational perspective [6,7]. In terms of the relationship between diverse learning environments and entrepreneurial intentions, little attention has been given to the intrinsic relationship between diverse learning environments and HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies, and it is mostly limited to the level of entrepreneurial awareness and entrepreneurial behavior.

In view of all this, this study takes a step further to investigate whether knowledge transfer among HE students can benefit from a diverse learning environment and improve their entrepreneurial competencies through self-efficacy and cognitive flexibility. As an attempt in this regard, this paper considers knowledge transfer as a key link between the interior (individual cognition) and exterior (diverse learning environment). Knowledge transfer is acknowledged as a process of transferring and knowledge application in different contexts, and as a beneficial skill in improving learners’ cognitive capacity [8,9] and stimulating their efficacy beliefs. In addition, self-efficacy increases HE students’ stamina to pursue goals in complex environments, strengthens their perseverance in the face of obstacles, their resilience to adversity, and their ability to manage stress when handling demanding tasks [10,11]. These latter qualities are thought to be important influencing factors on entrepreneurial competencies. Therefore, knowledge transfer facilitates HE students to maintain cognitive flexibility when adapting to changing environments, enabling them to come up with new ideas and potential solutions to new problems, thereby enhancing their innovative and entrepreneurial competencies [12].

With all the factors taken into account, the following two questions will be addressed in this paper: Is the diverse learning environment an important external factor in enhancing students’ entrepreneurial competencies? What mediating mechanism enables the external environmental conditions to act on the individual’s internal cognition and thereby enhance their entrepreneurial competencies? Conceptually, this research takes an initiative and has established a model to predict the theoretical and practical effects of a diverse learning environment on HE student’s entrepreneurship education and has provided a research perspective on enhancing entrepreneurial competencies through offering an appropriate learning environment. In the model, we also have an explanation of the mechanism and internal logic between a diverse learning environment and HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies via knowledge transfer and individual cognitive evaluation. This research provides a fresh perspective on how to foster entrepreneurship and the entrepreneurial competencies of HE students, which helps to improve the diverse learning environment of universities, foster an innovative and entrepreneurial environment, and enhance college students’ entrepreneurial competencies. More importantly, this research has important practical implications for universities to build a sustainable entrepreneurship education system, promote HE students’ innovation and entrepreneurship, and improve the success rate of entrepreneurship [6,13,14].

2. Research Hypotheses and the Theoretical Model

2.1. The Mediating Role of Knowledge Transfer

As an important feature of university education, a diverse learning environment helps stimulate students’ cognitive growth and creative thinking, thereby improving their skills in various domains [7,15]. Such benefits cannot be achieved without a continuous knowledge flow and individuals’ personal experiences resulting from their adaptation to the environment and vice versa [6,7]. On the one hand, a continuous knowledge flow is manifested in the transferability of knowledge. The openness, inclusiveness, and complexity of the diverse learning environment not only facilitates the sharing, exchange, understanding, and application of knowledge between individuals and external elements but also helps individuals train and enhance their metacognition [7,9]. On the other hand, differences in the diverse learning environment spur the growth of individuals’ cognition. Students reinforce their intellectual performance and develop critical thinking in resolving psychological conflicts and experimenting with new ideas and relationships, which are crucial abilities that contribute to the success of knowledge transfer [7,8]. From a constructivist standpoint, Garraway (2011) stressed that knowledge transfer spawns a metacognitive reflective ability [9]. Specifically, through reflective transfer, students take into account the changes and needs of different situations to expand their knowledge in a new context, which not only helps them consolidate their existing knowledge but also promotes the generation of new knowledge [9]. Therefore, continuous knowledge transfer enables HE students to take in knowledge efficiently, enhance their positive perception of themselves, and improve their self-efficacy [9,16,17]. In addition, by changing their cognitive sets in response to changes in the environment, HE students strengthen their positive attitudes toward changes and maintain diverse representations of knowledge, information, and behavioral patterns in their cognitive repertoire, thus forming flexible cognitive habits and increasing cognitive flexibility [12,18]. In sum, knowledge transfer is a powerful mediator of the interaction between individuals and their diverse learning environment. The process of knowledge absorption in such environments not only reflects the knowledge transfer mechanism but also enhances HE students’ positive perceptions of their self-learning abilities as well as the knowledge, skills, and successful experiences they possess. It also engages HE students in higher-order attentional control strategies and strengthens their cognitive flexibility through cognitive enhancement [12].

Therefore, the hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Knowledge transfer mediates the relationship between diverse learning environment and self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Knowledge transfer mediates the relationship between diverse learning environment and cognitive flexibility.

2.2. The Mediating Effects of Self-Efficacy and Cognitive Flexibility

Self-efficacy, defined as confidence in successfully executing a task or accomplishing a goal, is vital in building individuals’ strength and increasing their psychological capital [19]. Krueger et al. (1994) argued that fostering entrepreneurial self-efficacy is even more important than actual skills [20,21]. From a psychological capital perspective, self-efficacy, as a positive psychological state [19], provides individuals with higher levels of control, such as more resilience, endurance, and perseverance in the face of difficult tasks. It also motivates them to maintain higher levels of motivation and interest, as well as beliefs and expectations, which translate into higher levels of perceived entrepreneurial competencies [10,19]. Meanwhile, Schunk (1989) believed that individuals with high self-efficacy tend to be more engaged in entrepreneurial task learning and use cognitive processes that facilitate learning, rehearsing, reasoning, as well as mentally organizing information to enrich their entrepreneurial knowledge and abilities [16,22]. Moreover, self-efficacy is dynamic and subject to personal achievements [19,23,24], while knowledge transfer helps students to develop a pattern of knowledge absorption based on situational knowledge application, by consistently applying new knowledge and skills until satisfactory performance is achieved [25]. Thus, continuous knowledge transfer helps to promote efficient knowledge learning and experience application among HE students, stimulating efficacy beliefs and empowering the shift to higher-order entrepreneurial competency acquisition [16,19].

Cognitive flexibility is one of the important factors influencing intelligence and creativity [26,27] and is conducive to improving individuals’ understanding of and adaptation to different situations that result in timely cognitive and behavioral changes [18,28]. On the one hand, as a specific ability or mechanism, cognitive flexibility facilitates individuals to creatively combine knowledge, fully understand the environment, and expand problem-solving solutions, thereby advancing their ideational fluency and the ability to cope with complex problems [12,27]. On the other hand, it also helps improve individuals’ opportunity recognition capability and innovative creativity by empowering them to break old cognitive patterns, shake off restrictive cognitive chains, and make novel associations between entrepreneurial concepts [29,30]. Thus, cognitive flexibility enhances HE students’ perceived entrepreneurial competencies by increasing their adaptability to different things with openness and tolerance, in addition to improving their skills to perceive, offer feedback, and communicate with others [29,31]. Orakcı (2021) indicated that the ability to understand knowledge and create it in multiple ways contributes to the development of cognitive flexibility [28]. In the process of knowledge transfer, students need not only to enumerate knowledge but also to consider transferring situations for the development and creation of new knowledge [32], so as to deepen their understanding of existing knowledge and develop the abilities to perceive situations with diverse perspectives for further knowledge production [18].

In summary, the diverse learning environment at universities, as an important background, stimulates pluralistic, multifaceted, and multi-subject knowledge transfer within the campus, prompting students to effectively absorb knowledge and generate new knowledge. This is not only conducive to shaping students’ positive self-efficacy beliefs but also to developing flexible cognitive thinking habits and patterns, which in turn leads to the enhancement of HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies. Therefore, the specific hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between knowledge transfer and entrepreneurial competencies.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Cognitive flexibility mediates the relationship between knowledge transfer and entrepreneurial competencies.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Knowledge transfer and self-efficacy play a chain-mediating role between diverse learning environment and entrepreneurial competencies.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Knowledge transfer and cognitive flexibility play a chain-mediating role between diverse learning environment and entrepreneurial competencies.

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Entrepreneurship Education

Entrepreneurship education plays a crucial role in improving students’ entrepreneurial competencies [33]. As a powerful means of influencing students’ mindsets, attitudes, and behaviors [34], it is fundamental to triggering effective entrepreneurial behavior in students [35]. To begin with, high involvement in entrepreneurship education contributes to the development of students’ entrepreneurial knowledge and efficacy beliefs [34,36] by providing them with the requisite mix of theoretical knowledge, practical skills, and entrepreneurial experience, thereby improving their understanding of and confidence in entrepreneurship [33,37]. Consequently, students have greater self-efficacy [36] and are more motivated to engage in higher-order entrepreneurial exercise [36], acquiring both theoretical knowledge and practical skills [38]. Summing up, entrepreneurship education reinforces the positive impact of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial competencies.

Moreover, entrepreneurship education is not only about teaching students to start a business but also about developing an entrepreneurial mindset that enables them to actively and innovatively seek opportunities and turn them into successful commercial ventures [39]. Students with a high level of involvement in entrepreneurship education are more likely to demonstrate a higher level of situational understanding and adaptability and present a multi-hypothesis, multi-solution, multi-possibility mindset [37]. As a result, involvement in entrepreneurship education stimulates students’ cognitive flexibility and improves their ability to create, identify opportunities, and solve complex problems [37]. To sum up, entrepreneurship education activates students’ cognitive flexibility and positively influences the effect of cognitive flexibility on entrepreneurial competencies.

Therefore, the specific hypotheses take the following forms:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Entrepreneurship education has a positive moderating effect between self-efficacy and entrepreneurial competencies.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Entrepreneurship education has a positive moderating effect between cognitive flexibility and entrepreneurial ability.

2.4. Theoretical Model

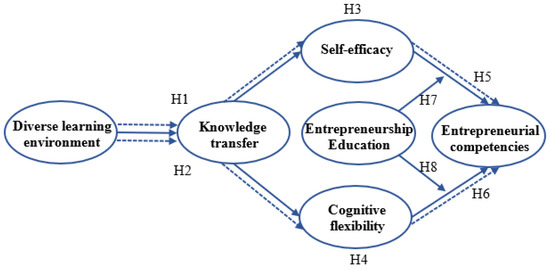

In the light of the foregoing, this study constructs a theoretical model integrating internal and external influencing factors, to capture the influence of a diverse learning environment on HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies (see Figure 1), based on a systematic and comprehensive literature review. In this model, diverse learning environment, knowledge transfer, self-efficacy, and cognitive flexibility are the four primary factors that affect HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies. Entrepreneurship education is an important moderating variable in the relationship between self-efficacy and entrepreneurial competencies and between cognitive flexibility and entrepreneurial competencies. A questionnaire survey was conducted among HE students, with the model tested using structural equation modeling.

Figure 1.

A Theoretical Model of Entrepreneurial Competencies.

3. Methodology

3.1. Variable Measurement

The variables in this study were measured with established scales, and a 7-point Likert scale anchored at 1 (totally disagree) and 7 (totally agree) was used for the questionnaire survey. In order to ensure the accuracy and validity of the translation, and to guarantee that the respondents understand the meaning of the questions correctly, a “translation and back translation” approach was employed in this study [40]. To be specific, a preliminary Chinese translation of the scale was produced by several educational experts and professional translators before being adapted as appropriate to the subject matter of this study. This version was then translated back to English by additional translation experts. Finally, a questionnaire was developed by rationalizing the items through several discussions to avoid semantic ambiguities and improve the applicability of the scale [41]. This study involves a total of six research variables: diverse learning environment, knowledge transfer, self-efficacy, cognitive flexibility, perceived entrepreneurial competencies, and entrepreneurship education. It also involves four control variables: gender, work experience, grade level, and academic discipline. The specific sources of the measurement items for each research variable are as follows:

- (1)

- Diverse learning environment (DLE). This variable is based on Haddad et al.’s scale [6] and contains items such as “Encourages students to have a public voice and share their ideas openly” and “Has a long-standing commitment to diversity”. The internal reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α) of the variable is 0.949.

- (2)

- Knowledge transfer (KNT). This variable is borrowed from Tho et al.’s measurement scale [42] and comprises items such as “I acquire a lot of knowledge and skills needed for my current job” and “I acquire a lot of knowledge and skills that helps me to enhance my job performance”. The Cronbach’s α of the variable is 0.910.

- (3)

- Self-efficacy (SEE). This variable builds on Chen et al.’s scale [19], including items such as “I feel confident analyzing a long-term problem to find a solution” and “In my future job, I feel confident in representing my field of study in the future”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the variable is 0.910.

- (4)

- Cognitive flexibility (COF). Drawn from Dang et al.’s scale [43], this variable consists of items such as “I come up with creative ideas by thinking in many different directions” and “I think out of the box to explore unconventional approaches”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the variables is 0.949.

- (5)

- Entrepreneurial competencies (EC). Under this variable, taken from Boubker et al.’s scale [1], are items such as “I understand how to start an entrepreneurial project” and “I am able to seize business opportunities”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the variable is 0.949.

- (6)

- Entrepreneurship education (ENE). This variable stems from Zhang et al.’s scale [5] and is composed of items such as “Our major courses are full of creativity and catch the trends of travel and hospitality.” and “Our majors often conduct experiment practice and field study arrangements”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the variables is 0.968.

- (7)

- Control variables. In this study, gender, work experience, grade level, and academic discipline are used as control variables in light of the studies by Haddad et al. [6], Zhang et al. [5], and Wang et al. [44] on HE students’ innovation and entrepreneurship.

3.2. Subjects and Sampling

Data for this study were collected between December 2021 and January 2022, through electronic questionnaires distributed online to students at three schools, namely Huaqiao University, Jimei University, and Xiamen University of Technology. To be specific, the study sample includes only students from the second year of undergraduate to the third year of postgraduate period, who were asked to comment on the entrepreneurship education and its associated support at their schools. In the study, two research assistants from each of the above three universities were invited to send out electronic questionnaires to multiple colleges and disciplines in their schools and to provide detailed answers to respondents’ questions. A total of 581 responses were received, and after cleaning and screening for missing data, careless answers, and outliers [6], a final sample of 505 valid responses was obtained for hypothesis testing. Table 1 details the demographics of the students in this study.

Table 1.

Demographic Analysis.

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Correlation Analysis

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of the respective variables, indicating a high correlation among them. The presence of collinearity is tested using the variance inflation factor (VIF) [45]. It is revealed that the highest VIF value is 3.800 (less than 5.0), suggesting the absence of collinearity in this study [46]. In addition, by calculating the square roots of the average variance extracted values (AVE) and comparing them with the correlation coefficients of the variables, it can be concluded that, because the square root of the AVE between any two variables is higher than the correlation coefficient between the two, all variables are well-measured by their items with good data discriminant validity [47].

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics, Correlation Coefficients, and Discriminant Validity.

4.2. Common Method Bias Test

The data in this study were collected through questionnaires. Despite efforts to minimize a common method bias by counterbalancing question order, avoiding double-barreled questions, defining key terms, and adequately assuring the respondents of the anonymity in the opening statement, the possibility of a common method bias cannot be completely ruled out, as the variables of the questionnaires were filled by the same respondents [45]. Therefore, a potential error variable control was conducted to test the common method bias, which is introduced as a latent variable into the structural equation model [48], turning the original six-factor model into a seven-factor one. The results, as shown in Table 3, indicate that Chi-square values change significantly after the control (Δχ2 = 144.967), but the changes in CFI, IFI, TIL, NFI, GFI, and RMSEA are not significant, implying that there is no significant common method bias among the variables in this study.

Table 3.

Results of Common Method Bias Test.

4.3. Reliability Analysis

First, as shown in Table 4, the standardized factor loadings of all the measurement items of the variables meet the threshold requirements (standardized factor loadings > 0.5). Second, the Cronbach’s α values of all the variables are greater than 0.9, indicating their good reliability [49]. Finally, according to Fornell, the combined reliability (C.R.) of the latent variables and AVE values are good indicators of convergent validity [47]. The C.R. values of the variables in this study range from 0.911 to 0.968, in line with the threshold limit proposed by Hair et al. (C.R. > 0.7) [49], meaning that the variables have high internal consistency. Meanwhile, the AVE values of all the variables in this study are between 0.721 and 0.862, meeting the criteria for convergent validity (AVE > 0.5) [47], which implies that the variables are in an ideal state. The above indicates that all the variables have good reliability.

Table 4.

Reliability and Convergent Validity.

4.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To further test the differentiation of the variable constructs in this study and the fit between the model and the data, a confirmatory factor analysis with model fit as the indicator was conducted using AMOSS21.0 software on diverse learning environment, knowledge transfer, self-efficacy, cognitive flexibility, perceived entrepreneurial competencies, and entrepreneurship education [50]. The results of the analysis are shown in Table 5, where the six-factor model has the best data fit and outperforms the other nested models. Thus, the six-factor model is well suited for a further data analysis as all its fit values meet the reference criteria.

Table 5.

Results of Discriminant Validity Analysis.

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

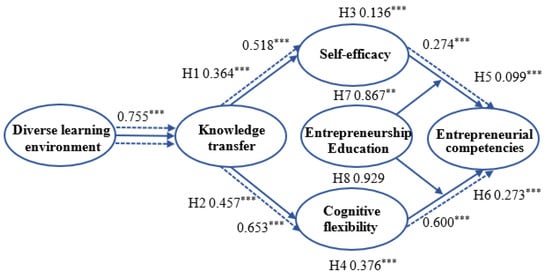

In this study, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to analyze the direct, mediating, and moderating effects of the data using AMOSS 21.0 software. SEM is a multivariate statistical method that integrates factor analysis and path testing [51]. Importantly, it enables the simultaneous testing of all variable systems in a hypothesis model, maximizing the fit of the hypothesis model to the data [52]. In addition, the bootstrapping method with the Monte Carlo approach, with 2000 estimations and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals, was also utilized [5]. The detailed test results are shown in Figure 2, where all the direct paths are significant and all the goodness-of-fit indexes reach standard values [53] (χ2/df = 4.018, CFI = 0.948, IFI = 0.948, TLI = 0.944, NFI = 0.932, GFI = 0.869, AGFI = 0.846, RMSEA = 0.077). This is followed by the mediating and moderating hypothesis tests.

Figure 2.

Model Results. Note: the dotted lines show the chain-mediating paths for H5 and H6; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

(1) H1 posits that diverse learning environment influences self-efficacy through knowledge transfer. The results indicate a significant positive correlation between diverse learning environment and knowledge transfer (β = 0.755, p < 0.001) as well as a significant positive effect of knowledge transfer on self-efficacy (β = 0.518, p < 0.001). As shown in Table 6, the indirect effect of knowledge transfer between diverse learning environment and self-efficacy is significant (β = 0.364, p < 0.001). H2 states that knowledge transfer plays a mediating role between diverse learning environment and cognitive flexibility. The results reveal that knowledge transfer has a significant positive effect on cognitive flexibility (β = 0.653, p < 0.001) and plays a significant moderating role between diverse learning environment and cognitive flexibility (β = 0.457, p < 0.001). H1 and H2 are therefore confirmed.

Table 6.

Tests of Mediated Outcomes.

(2) H3 assumes that knowledge transfer influences perceived entrepreneurial competencies through self-efficacy. The results suggest that self-efficacy has a significant positive correlation with perceived entrepreneurial competencies (β = 0.274, p < 0.001), as shown in Table 6, and the indirect effects of knowledge transfer on perceived entrepreneurial competencies through the mediation of self-efficacy are all statistically significant (β = 0.136, p < 0.001); thus, H3 holds.

(3) H4 says that knowledge transfer affects perceived entrepreneurial competencies through cognitive flexibility. The results illustrate that there is a significant positive correlation between cognitive flexibility and perceived entrepreneurial competencies (β = 0.600, p < 0.001). As shown in Table 6, the indirect effect of knowledge transfer on perceived entrepreneurial competencies through the mediation of cognitive flexibility is significant (β = 0.376, p < 0.001); therefore, H4 is supported.

(4) As suggested by Liu, the bias-corrected nonparametric percentile bootstrap method was applied to test chain-mediating effects, with 2000 re-samplings and bootstrap confidence intervals excluding 0 [50]. The test results of H5 and H6 demonstrate that, “knowledge transfer → self-efficacy” and “knowledge transfer → cognitive flexibility” both have significant chain-mediating effects in the relationship between diverse learning environment and perceived entrepreneurial competencies (β = 0.099, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.054, 0.153]; β = 0.273, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.199, 0.354]). Therefore, H5 and H6 are true.

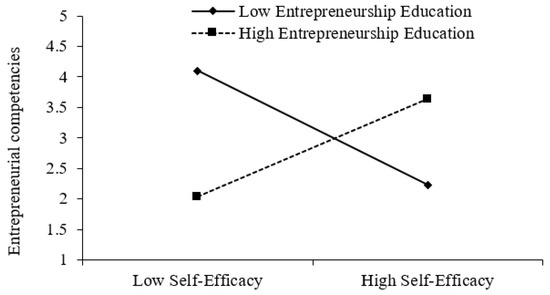

(5) A structural equation modeling analysis with the inclusion of a product term was performed to examine the moderating effect of entrepreneurship education [54]. The results are shown in Table 7, where the effect of the interaction term between self-efficacy and entrepreneurship education on the dependent variable is significant (β = 0.867, p = 0.003). However, the interaction term between cognitive flexibility and entrepreneurship education has a non-significant effect on the dependent variable (β = 0.929, p = 0.222). The interaction effects are plotted in Figure 3 to display the moderating effects.

Table 7.

Tests of Moderating Effects.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on the Relationship between Self-efficacy and Entrepreneurial Competencies.

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

By developing a theoretical model of the influence of diverse learning environments on HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies, this study further investigated the impact of diverse learning environments on the entrepreneurial competencies of HE students. The study’s specific findings are listed below.

The diverse learning environment, as one of the basic features of modern education, is an important external element for the development of university students’ entrepreneurial competencies. The present study confirms the positive influence of diverse learning environments on HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies from an external environment perspective [6]. Haddad (2021) et al. argued that HE students in a diverse learning environment exhibit more positive entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors [6]. Adding to their finding, it is found here that a diverse learning environment, as an important external factor, can enhance HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies by significantly boosting their sense of self-efficacy and cognitive flexibility through knowledge transfer. HE students develop complex thinking patterns and flexible cognition as well as the ability to adapt to higher levels of challenges in entrepreneurship education [7,55], which leads to high performance in various complex and realistic entrepreneurship simulation projects, coupled with great learning growth and capacity. In light of empirical learning theories, diverse situational interactions among HE students are an efficient learning mode for growing their cultural intelligence and practical skills [56] conducive to improving their entrepreneurial competencies. Therefore, the diverse learning environment is an important external influencing factor for entrepreneurial capacity enhancement among HE students.

Self-efficacy and cognitive flexibility are important cognitive elements in increasing HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies. Knowledge transfer not only serves as a key link through which the external learning environment exerts its influence on individuals’ cognition but also plays a mediating effect, together with self-efficacy and cognitive flexibility, for the diverse learning environment to shape entrepreneurial capacity. Bennett et al. (1986) pointed out that students’ knowledge absorption is prone to “being discounted” in the traditional classroom knowledge transfer model [56,57]. The results of this study further clarify this problematic issue by validating that knowledge transfer is a critical intermediate link between the interior (individual cognition) and exterior (diverse learning environment). It helps students adapt to the complexity and diversity of their interactions with external elements [7,56] and strengthens their self-efficacy and cognitive flexibility by enabling them to receive, understand, and apply existing knowledge with a greater metacognitive reflection capacity [9]. In addition, the present study demonstrates that self-efficacy and cognitive flexibility are two important factors in activating students’ cognitive learning capabilities [18]. On the one hand, self-efficacy helps foster HE students’ sense of control and positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship, facilitating them to acquire greater entrepreneurial competencies through continuous entrepreneurial learning and complex problem solving [16,19]. On the other hand, cognitive flexibility contributes to updating HE students’ cognitive models and developing their abilities to create knowledge, seek opportunities, and solve problems in different contexts, which are crucial in the early stages of their entrepreneurship [12,29]. Therefore, HE students can easily realize the enhancement of entrepreneurial competencies in a diverse learning environment through the “transition” of continuous knowledge transfer and the exercise of individual cognitive elements.

Entrepreneurship education significantly enhances the influence of self-efficacy on HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies; however, it does not play a moderating role between cognitive flexibility and competencies. In a positive entrepreneurship education context, HE students can acquire solid theoretical knowledge and rich practical skills, which helps them develop a high degree of self-affirmation and confidence in entrepreneurship [33,35] while committing themselves to improving their entrepreneurial competencies. This study empirically demonstrated that entrepreneurship education can enhance the positive influence of self-efficacy on HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies, which is consistent with Shen et al.’s (2021) research that found “education and training can cultivate self-efficacy, enhance entrepreneurial competencies, and develop desirable entrepreneurial performance [58]”. Furthermore, this study shows that entrepreneurship education does not play a moderating role in the relationship between cognitive flexibility and HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies. Saeed (2015), in discussing the impact of university entrepreneurship support on entrepreneurial intentions, noted that the disconnection between college entrepreneurship education and the business world as well as the lack of a practical business-oriented educational attitude [59,60] make it difficult to coordinate entrepreneurship education with business needs, or to simulate complex business networks for training. That is, entrepreneurship education fails to adequately improve HE students’ cognitive flexibility or play a role in its influence on their entrepreneurial competencies. The findings of this study are in line with Saeed’s (2015) theoretical perspective.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study constructs a theoretical path of enhancing HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies by way of the external environment and clarifies the theoretical effects and practical roles of a diverse learning environment in university entrepreneurship education. As documented by the existing literature, a diverse learning environment is important for the enhancement of students’ comprehensive abilities [6,7,56] and has been proven to have a direct effect on their entrepreneurial intentions in the entrepreneurship domain [6]. However, previous studies have not only confined themselves to exploring the multidimensional cultivation and development of HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies from the perspective of university entrepreneurship education but also ignored the fact that diversity is one of the characteristics of modern university education and, as an implicit condition, is involved in the process of entrepreneurial competency development among HE students [61]. Therefore, little attention has been paid to the mechanism of entrepreneurial competency enhancement from the angle of the university education environment. In view of this, this paper probes into the enhancement of HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies from the viewpoint of a diverse learning environment. It explains the role of the diverse learning environment in the entrepreneurship education targeted at HE students and provides an innovative perspective for relevant research on HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies. This study echoes Haddad’s (2021) remark that “education managers could use the model to create educational environments that include diversity as a core part of the institution’s mission, policies, structure, and pedagogy” [6].

The correlation between a diverse learning environment and HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies are laid bare, and the process mechanism of knowledge transfer between the external learning environment and internal cognitive processes is elucidated. To begin with, while there is a consensus that a “diverse learning environment is critical to the development of individual competencies” [6,7], previous studies have provided little insight into the mediating effects between the two and have failed to systematically reveal the processes by which students benefit from a diverse learning environment. Therefore, this study creatively introduces knowledge transfer as an intellectual instrument embedded in the action pathway from a diverse learning environment to the enhancement of HE students’ cognitive and entrepreneurial competencies. The study shows that there is no direct causal relationship between a diverse learning environment and students’ ability growth. According to empirical learning theories, individuals’ “reflection and reception” during exposure to the external environment are effective transition factors for their ability growth [56]. The study not only unveils the theoretical “black box” of entrepreneurship enhancement but also enriches the literature in the field of knowledge transfer. Furthermore, the findings of this study uncover that knowledge transfer significantly enhances HE students’ self-efficacy and cognitive flexibility. These are comparable with Jaeggi’s (2011) research which concluded that both cognitive and metacognitive capacity can be developed through external training interventions [56] and validated that knowledge transfer is a favorable process mechanism. In brief, this study not only puts forward a novel theoretical approach to the enhancement of HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies but also underscores the key role of knowledge transfer in this regard.

The study reveals the differential effects of entrepreneurship education on HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies in different cognitive processes and expounds the conditions for the action of entrepreneurship education and the boundaries of its application. Previous studies are still highly contentious in terms of research on the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial competencies [62]. This study innovatively employs entrepreneurship education as a moderator for the effects of self-efficacy and cognitive flexibility on entrepreneurial competencies, highlighting, on the one hand, that entrepreneurship education is more likely to awaken positive entrepreneurial emotions and strengthen entrepreneurial competencies in HE students. On the other hand, it confirms that entrepreneurship education is difficult to stimulate cognitive flexibility in HE students and cannot have an impact on the relationship between cognitive flexibility and entrepreneurial competencies. This research does not only fill in a research gap on the boundaries of entrepreneurship education but also responds to the theoretical call from scholars that “a detailed assessment of the contextual dimensions of entrepreneurship education is necessary for the effective advancement of academic knowledge in the field” [62,63]. These findings have significant practical implications for how to design entrepreneurship education curriculum systems.

5.3. Practical Implications

This research significantly advances the development of entrepreneurial competencies among HE students. The study’s findings have significant practical implications for how to develop HE students’ competencies for knowledge transfer and help them exercise various cognitive processes in order to further develop their entrepreneurship competencies in a diverse learning environment.

The diverse learning environment should be taken as a core part of university education to play its important role in entrepreneurship. In terms of creating internal plurality, universities should take into account the diversity of students and teachers’ cultural backgrounds, values, and beliefs to create an open and inclusive campus culture [56]. Meanwhile, front-line instructors should engage in education with diverse pedagogical approaches, educational programs, and teaching systems, integrating cutting-edge academic findings, practical experiences, and successful cases of entrepreneurship into classroom teaching to guide students to explore the field of innovation and entrepreneurship on their own and enhance their entrepreneurial competencies. In terms of external pluralism, universities should encourage the establishment of a comprehensive interactive exchange system bridging theory and practice, with other parties such as higher education institutions, business organizations, and government departments [6]. Such a system will serve as an innovative and entrepreneurial talent cultivation mechanism by developing students’ broad horizons, diverse thinking, and comprehensive abilities through innovation and entrepreneurship competitions and trainings, entrepreneurial project exchanges, and lectures by entrepreneurial mentors.

An emphasis should be placed on knowledge transfer in order to develop students’ cognitive maturity and enhance their entrepreneurial self-efficacy and cognitive flexibility. This study demonstrates that knowledge transfer, self-efficacy, and cognitive flexibility play a crucial mediating role in enhancing entrepreneurial competencies among HE students. First, educators should strive to create opportunities for the exchange and interaction of different values, theoretical knowledge, and practical skills among students, by establishing clubs, organizing activities, and designing group assignments [6,7,56], for example. Second, entrepreneurship courses may allow for the transfer and expansion of students’ existing knowledge through such tasks as a case analysis and scenario simulation [5], which not only give them a glimpse into the operation of business systems but also build their capacities to analyze and deal with various scenarios. Last but not least, university education should also be dedicated to cultivating students’ self-efficacy and cognitive flexibility. On the one hand, universities should encourage students to practice entrepreneurship theories and internalize entrepreneurial knowledge by getting access to formal organized seminars, social networks, and intergenerational exchanges, in an effort to increase their entrepreneurial self-efficacy, competencies, and achievements [58]. On the other hand, the educational curriculum should deliver multidisciplinary trainings for students, developing their habit of seeing things from multiple perspectives [28,64]. Meanwhile, universities should break away from the traditional practice of assessing academic performance by “grades only” [17] and instead attach importance to stimulating students’ cognitive flexibility and enabling them to acquire the skills and abilities required for entrepreneurship.

The connection between university entrepreneurship education and social business networks should be consolidated to offer an education oriented at entrepreneurship and employment, so as to enhance HE students’ comprehensive qualities and entrepreneurial competencies. Theoretical learning and practical materialization of entrepreneurship should be strengthened in entrepreneurship education to equip students with the necessary entrepreneurial knowledge and skills [5], as well as positive beliefs of and attitudes toward entrepreneurship to boost their motivation [34]. The curriculum should include lectures and guidance from hands-on entrepreneurs [5] in line with the types of talents needed in the real business world, in order to develop HE students’ business sensitivity, creativity, and the ability to identify opportunities. In addition, the course design should introduce modern online virtual business projects, such as the CESIM Business Simulation Games, an international project aimed at promoting HE students’ innovation and entrepreneurship, which can not only inspire students’ interest in entrepreneurship but also improve their entrepreneurial mindsets and competencies.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study is believed to be of both theoretical and practical significance as it constructs an innovative theoretical model for the enhancement of HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies through diverse learning environments. However, it is not without limitations. The first one concerns the diverse learning environment which, though proven here to be an important external factor for developing HE students’ entrepreneurial competencies, is still an understudied topic in academia [6]. Future research can elaborate on the diverse environment and conduct an in-depth analysis of the influence of its multiple components on entrepreneurial competencies using an fsQCA analysis. The resultant findings can inform decision-makers to create a learning environment that is conducive to the sustainable development of HE students’ entrepreneurial capacities. The second limitation is that not all factors have been taken into account in this study. In view of the fact that entrepreneurial competencies are shaped not only by the entrepreneurship education climate within universities but also by various social elements such as government entrepreneurial support and economic location, future studies should give due consideration to the impact of the social entrepreneurial environment on HE students’ entrepreneurial capacities. Moreover, samples from other countries or regions are needed to generalize the findings of this study.

Author Contributions

Data instrument development, model development and original draft, H.C.; Literature review, data instrument development, and data collection and analysis, Y.T.; Providing resources and revision, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Huaqiao University Research Ethics Committee (protocol code: M2020010 and date of approval: 31 December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study. Written consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Boubker, O.; Arroud, M.; Ouajdouni, A. Entrepreneurship education versus management students’ entrepreneurial intentions. A PLS-SEM approach. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, B. Analysis on Entrepreneurship Psychology of Preschool Education Students With Entrepreneurial Intention. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arranz, N.; Arroyabe, M.F.; Fdez De Arroyabe, J.C. Entrepreneurial intention and obstacles of undergraduate students: The case of the universities of Andalusia. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 44, 2011–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, J. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Mediates the Impact of the Post-pandemic Entrepreneurship Environment on College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Ruan, W. Critical factors identification and prediction of tourism and hospitality students’ entrepreneurial intention. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 26, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, G.; Haddad, G.; Nagpal, G. Can students’ perception of the diverse learning environment affect their intentions toward entrepreneurship? J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Noman, M.; Nordin, H. Inclusive assessment for linguistically diverse learners in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 756–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aglen, B. Pedagogical strategies to teach bachelor students evidence-based practice: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 36, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garraway, J.; Volbrecht, T.; Wicht, M.; Ximba, B. Transfer of knowledge between university and work. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 16, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tseng, T.H.; Wang, Y.; Chu, C. Development and validation of an internet entrepreneurial self-efficacy scale. Internet Res. 2019, 30, 653–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-Effic. Beliefs Adolesc. 2006, 5, 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Dheer, R.J.; Lenartowicz, T. Cognitive flexibility: Impact on entrepreneurial intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreras-Garcia, R.; Sales-Zaguirre, J.; Serradell-Lopez, E. Developing entrepreneurial competencies in higher education: A structural model approach. Educ. Train. 2021, 63, 720–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchelmore, S.; Rowley, J. Entrepreneurial Competencies: A Literature Review and Development Agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosnacht, K.; Gonyea, R.M.; Graham, P.A. The Relationship of First-Year Residence Hall Roommate Assignment Policy with Interactional Diversity and Perceptions of the Campus Environment. J. High. Educ. 2020, 91, 781–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Chengang, Y.; Arbizu, A.D.; Haider, M.J. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: Do entrepreneurial creativity and education matter? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, S.; Ju, X. Knowledge transfer capacity of universities and knowledge transfer success: Evidence from university-industry collaborations in China. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2016, 71, 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, A.B.; Presbitero, A. Cognitive flexibility and cultural intelligence: Exploring the cognitive aspects of effective functioning in culturally diverse contexts. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2018, 66, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.J.; Lim, V.K. Strength in adversity: The influence of psychological capital on job search. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 811–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N., Jr.; Dickson, P.R. How believing in ourselves increases risk taking: Perceived self-efficacy and opportunity recognition. Decis. Sci. 1994, 25, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickul, J.; Gundry, L.K.; Barbosa, S.D.; Whitcanack, L. Intuition versus analysis? Testing differential models of cognitive style on entrepreneurial self–efficacy and the new venture creation process. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, B.; Liu, Y.; Bajaba, S.; Marler, L.E.; Pratt, J. Examining how the personality, self-efficacy, and anticipatory cognitions of potential entrepreneurs shape their entrepreneurial intentions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 125, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H. Self-efficacy and cognitive achievement: Implications for students with learning problems. J. Learn. Disabil. 1989, 22, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potosky, D.; Ramakrishna, H.V. The moderating role of updating climate perceptions in the relationship between goal orientation, self-efficacy, and job performance. Hum. Perform. 2002, 15, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururajan, V.; Fink, D. Attitudes towards knowledge transfer in an environment to perform. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Perceval, G.J.; Feng, W.; Feng, C. High cognitive flexibility learners perform better in probabilistic rule learning. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, T. Exploring the nature of cognitive flexibility. New Ideas Psychol. 2012, 30, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ORAKCI, Ş. Exploring the relationships between cognitive flexibility, learner autonomy, and reflective thinking. Think. Ski. Creat. 2021, 41, 100838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Hsiao, Y.; Chen, S.; Taung-Ta, Y. Core entrepreneurial competencies of students in departments of electrical engineering and computer sciences (EECS) in universities. Educ. Train. 2018, 60, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, S.M.; Damian, R.I.; Simonton, D.K.; van Baaren, R.B.; Strick, M.; Derks, J.; Dijksterhuis, A. Diversifying experiences enhance cognitive flexibility. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, M. Developing a cognitive flexibility scale: Validity and reliability studies. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2009, 37, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Ray, A.S. Choice of structure, business model and portfolio: Organizational models of knowledge transfer offices in british universities. Br. J. Manag. 2017, 28, 687–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayati, P.; Wulandari, D.; Soetjipto, B.E.; Wibowo, A.; Shandy Narmaditya, B. Does entrepreneurship education promote vocational students’ entrepreneurial mindset? Heliyon 2020, 6, e5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.M.; Khan, E.A.; Nabi MN, U. Entrepreneurial education at university level and entrepreneurship development. Educ. Train. 2017, 59, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Silva, R.; Franco, M. Entrepreneurial Attitude and Intention in Higher Education Students: What Factors Matter? Entrep. Res. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Raza, A.; Sajid, M.; Rafiq, M.; Hameed, R.; Ali, T. Entrepreneurial intentions: The relevance of nature and nurture. Educ. Train. 2021, 63, 1195–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Paço, A.; Ferreira, J.M.; Raposo, M.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Anabela Dinis, A. Entrepreneurial intentions: Is education enough? Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, S.; Aliakbari, A.; Majd, A.A.; Bell, R. The effect of entrepreneurship education on graduate students’ entrepreneurial alertness and the mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset. Educ. Train. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sha, Y.; Wang, J.; An, L.; Chen, T.; Huang, X.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L. How entrepreneurship education at universities influences entrepreneurial intention: Mediating effect based on entrepreneurial competence. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Qureshi, I.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Q. Corporate Social Responsibility and Disruptive Innovation: The moderating effects of environmental turbulence. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1435–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.; Brislin, R.; Stewart, V.; Werner, O. Back-translation and other translation techniques in cross-cultural research. Int. J. Psychol. 1970, 30, 681–692. [Google Scholar]

- Tho, N.D.; Trang, N.T.M. Can knowledge be transferred from business schools to business organizations through in-service training students? SEM and fsQCA findings. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisovich, M.N.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Wang, J.; Nguyen, N. How can frontline managers’ creativity in the hospitality industry be enhanced? Evidence from an emerging country. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 593–603. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Mundorf, N.; Salzarulo-McGuigan, A. Entrepreneurship education enhances entrepreneurial creativity: The mediating role of entrepreneurial inspiration. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 20, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 885, 10–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RMarkel, K.S.; Frone, M.R. Job characteristics, work—School conflict, and school outcomes among adolescents: Testing a structural model. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.S. Examining social capital, organizational learning and knowledge transfer in cultural and creative industries of practice. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tho, N.D. A configurational role of human capital resources in the quality of work life of marketers: FsQCA and SEM findings from Vietnam. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 13, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Hou, J.; Marsh, H. Analysis method of latent variable interaction effect. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 1996, 11, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Loes, C.; Pascarella, E.; Umbach, P. Effects of diversity experiences on critical thinking skills: Who benefits? J. High. Educ. 2012, 83, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Shen, G.Q. How formal and informal intercultural contacts in universities influence students’ cultural intelligence? Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2020, 21, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.M. Modes of cross-cultural training: Conceptualizing cross-cultural training as education. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1986, 10, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Hua, D.; Zhang, Z. Entrepreneurial learning, self-efficacy, and firm performance: Exploring moderating effect of entrepreneurial orientation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 731628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, G.H.S.M.; Fischer, B.B.; Guerrero, M.; da Rocha, A.K.L.; Schaeffer, P.R. An inquiry into the linkages between university ecosystem and students’ entrepreneurial intention and self-efficacy. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Yousafzai, S.Y.; Yani De Soriano, M.; Muffatto, M. The role of perceived university support in the formation of students’ entrepreneurial intention. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 1127–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, J. Linking entrepreneurial learning to entrepreneurial competencies: The moderating role of personality traits. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, D.; Minola, T.; Bosio, G.; Cassia, L. The impact of entrepreneurship education on university students’ entrepreneurial skills: A family embeddedness perspective. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A.; Krueger, N.; Walmsley, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klucznik-Törő, A. The New Progression Model of Entrepreneurial Education—Guideline for the Development of an Entrepreneurial University with a Sustainability Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).