Relevant Variables in the Stimulation of Psychological Well-Being in Physical Education: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

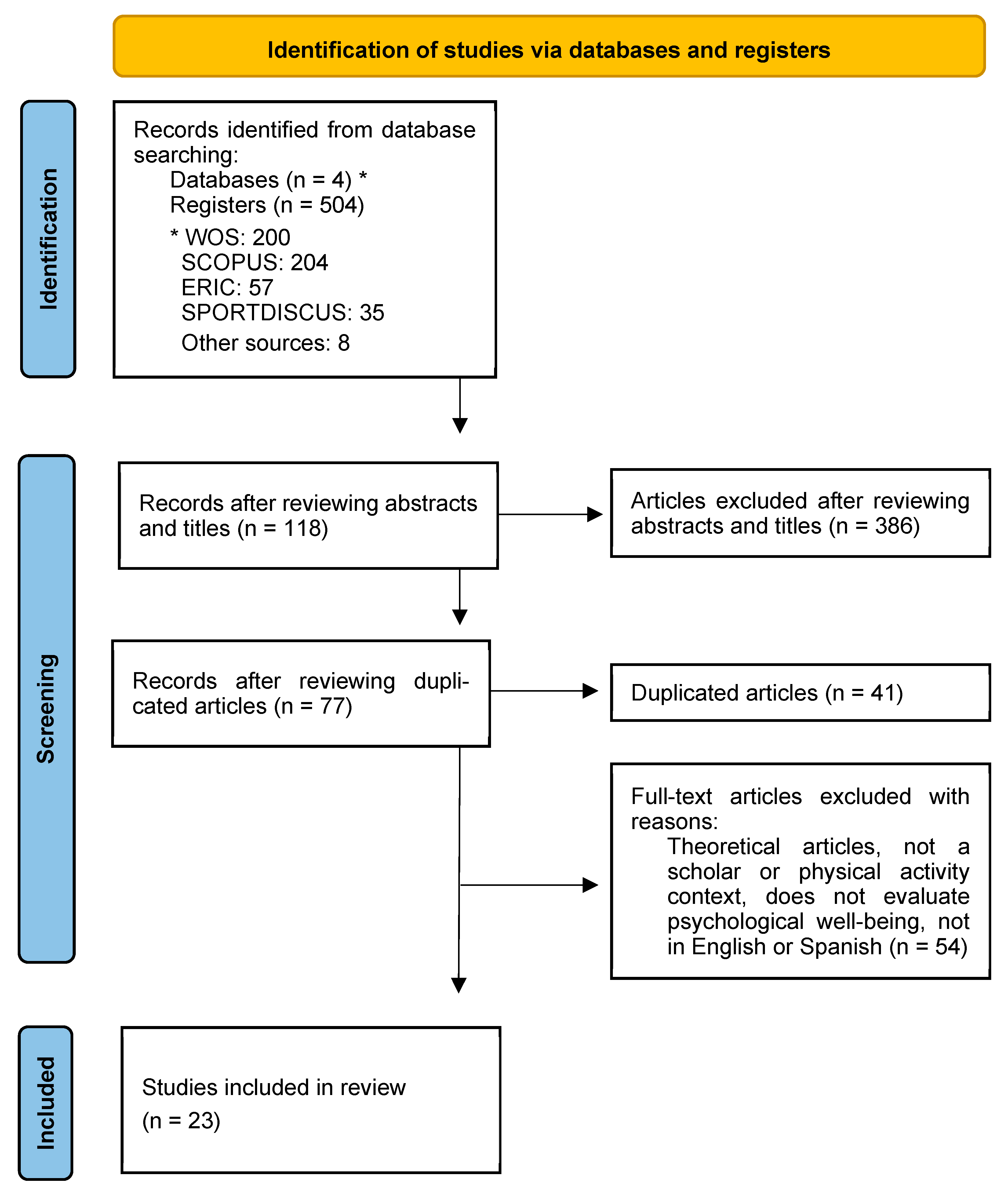

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

- P = child, children, boys, girls, adolescents;

- I = physical education;

- C = no comparison group was added to the search;

- O = psychological well-being, eudaemonic well-being.

2.2. Selection Criteria

- Studies involving a specific population with any type of physical, cognitive or psychological impairment;

- Articles not providing primary data (non-interventions) because they do not ensure methodological and statistical rigor (reviews, conceptual articles, conference proceedings, editorials, doctoral theses, books, opinion articles, etc.);

- Instrument validations.

2.3. Data Extraction and Reliability

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Studies

3.2. Employed Grade Levels Selected

3.3. Focus of the Studies and Context

3.4. Types of Associated Variables

3.5. Definition of PW

3.6. Research Results

3.6.1. Psychological Well-Being (PW)

3.6.2. Results Related to BPN

3.6.3. Academic Performance

3.6.4. Specific Programs

3.6.5. Environment in PE Classes

3.6.6. Exercise/PA

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Bremner, J.D.; Walker, J.D.; Whitfield, C.; Perry, B.D.; Dube, S.R.; Giles, W.H. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, I.; Murray, J.; Abbott, R.A.; Maughan, B.; Kuh, D.; Croudace, T.J.; Jones, P.B. Outcomes of conduct problems in adolescence: 40 year follow-up of national cohort. BMJ 2009, 338, a2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kessler, R.C.; Amminger, G.P.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Lee, S.; Ustün, T.B. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2007, 20, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Mortier, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hasking, P.; et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Hunt, J.; Speer, N. Mental Health in American Colleges and Universities: Variation Across Student Subgroups and Across Campuses. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2013, 201, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, W.C.; Strine, T.W.; Pratt, L.A.; Thompson, W.; Ahluwaliaet, I.; Dhingra, S.S.; McKnight-Eily, L.R.; Harrison, L.; D’Angelo, D.V.; Williams, L.; et al. Mental illness surveillance among adults in the United States. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2011, 60, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, H.; Boardman, C.; Dawkins, J.; Jennifer, D. Emotional Health and Well-Being: A Practical Guide for Schools; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780761943556. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzichristou, C. Alternative School Psychological Services: Development of a Databased Model. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 27, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, P.J.; Doll, B.; Song, S.Y.; Radliff, K. Transforming School Mental Health Services Based on a Culturally Responsible Dual-Factor Model. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.A.; Dyson, J.; Cowdell, F.; Watson, R. Do universal school-based mental health promotion programmes improve the mental health and emotional wellbeing of young people? A literature review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e412–e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivers, I.; Noret, N. Well-Being Among Same-Sex- and Opposite-Sex-Attracted Youth at School. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 37, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Rahman, A. Editorial Commentary: An agenda for global child mental health. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2015, 20, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, S.J.; Asare, M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pastor, D.; Cervelló, E.; Peruyero, F.; Biddle, S.; Montero, C. Acute physical exercise intensity, cognitive inhibition and psychological well-being in adolescent physical education students. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 5030–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidzan-Bluma, I.; Lipowska, M. Physical Activity and Cognitive Functioning of Children: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McMahon, E.M.; Corcoran, P.; O’Regan, G.; Keeley, H.; Cannon, M.; Carli, V.; Wasserman, C.; Hadlaczky, G.; Sarchiapone, M.; Apter, A.; et al. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and well-being. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, B.W.; Driscoll, S.W. Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents. PM&R 2012, 4, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedegaard, S.; Christiansen, L.B.; Lund-Cramer, P.; Bredahl, T.; Skovgaard, T. Improving the well-being of children and youths: A randomized multicomponent, school-based, physical activity intervention. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piñeiro-Cossio, J.; Fernández-Martínez, A.; Nuviala, A.; Pérez-Ordás, R. Psychological Wellbeing in Physical Education and School Sports: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J. World Happiness Report; University of British Columbia Library: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladis, M.M.; Gosch, E.A.; Dishuk, N.M.; Crits-Christoph, P. Quality of Life: Expanding the Scope of Clinical Significance. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 67, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikmund, V. Health, well-being, and the quality of life: Some psychosomatic reflections. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2003, 6, 401–403. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being and How to Achieve Them; Nicholas Brealey Publishing: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 9781439190753. [Google Scholar]

- Huta, V.; Waterman, A.S. Eudaimonia and Its Distinction from Hedonia: Developing a Classification and Terminology for Understanding Conceptual and Operational Definitions. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 1425–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samman, E. Psychological and Subjective Well-being: A Proposal for Internationally Comparable Indicators. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2007, 35, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. The Contours of Positive Human Health. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W. Toward a Unifying Theoretical and Practical Perspective on Well-Being and Psychosocial Adjustment. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 482–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Diener, E.; Schwarz, N. Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 9781610443258. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A.S. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissing, M.P.; van Eeden, C. Empirical Clarification of the Nature of Psychological Well-Being. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2002, 32, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reekum, C.M.; Urry, H.L.; Johnstone, T.; Thurow, M.E.; Frye, C.J.; Jackson, C.A.; Schaefer, H.S.; Alexander, A.L.; Davidson, R.J. Individual Differences in Amygdala and Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Activity are Associated with Evaluation Speed and Psychological Well-being. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007, 19, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being. In The Science of Well-Being; Diener, E., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 37, pp. 11–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, A. The Scales of Psychological Well-being: A Study of Validity and Reliability. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2008, 8, 741–750. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D. Well-Being with Soul: Science in Pursuit of Human Potential. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother. Psychosom. 2014, 83, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781462528769. [Google Scholar]

- War, P. A study of psychological well-being. Br. J. Psychol. 1978, 69, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.J.; McAdams, D.P.; Pals, J.L. Narrative identity and eudaimonic well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R. The Development of an Operational Concept of Psychological Wellbeing. Ph.D. Thesis, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, C.; Vázquez, C. Emociones positivas y crecimiento postraumático en el cáncer de mama. Psicooncología 2007, 4, 385–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H.; Dienberg Love, G. Positive health: Connecting well–being with biology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Urry, H.L.; Nitschke, J.B.; Dolski, I.; Jackson, D.C.; Dalton, K.M.; Mueller, C.J.; Rosenkranz, M.A.; Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H.; Davidson, R.J. Making a Life Worth Living: Neural Correlates of Well-Being. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.J.; Edwards, S.D.; Basson, C.J. Psychological Well—Being and Physical Self-Esteem in Sport and Exercise. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2004, 6, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.D.; Ngcobo, H.S.; Edwards, D.J.; Palavar, K. Exploring the relationship between physical activity, psychological well-being and physical self- perception in different exercise groups. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2006, 27, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, A.; Grishchuk, E.; Rogal, N.; Potop, V.; Korobeynikov, G.; Glazyrin, I.; Glazyrina, V.; Gorascenco, A.; Korobeynikova, L.; Dudnyk, O. The Influence of Physical Activity on Students’ Psychological Well-Being. Rev. Rom. Pentru Educ. Multidimens. 2020, 12, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Williams, G.C.; Patrick, H.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and Physical Activity: The Dynamics of Motivation in development and wellness. Hell. J. Psychol. 2009, 6, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sebire, S.J.; Jago, R.; Fox, K.R.; Edwards, M.J.; Thompson, J.L. Testing a self-determination theory model of children’s physical activity motivation: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opstoel, K.; Chapelle, L.; Prins, F.J.; De Meester, A.; Haerens, L.; van Tartwijk, J.; De Martelaer, K. Personal and Social Development in Physical Education and Sports: A Review Study. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 26, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagøien, T.E.; Halvari, H.; Nesheim, H. Self-Determined Motivation in Physical Education and Its Links to Motivation for Leisure-Time Physical Activity, Physical Activity, and Well-Being in General. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2010, 111, 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, I.; Anderssen, S.A.; Tjomsland, H.E.; Skulberg, K.R.; Thurston, M. Physical activity, mental health and academic achievement: A cross-sectional study of Norwegian adolescents. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2020, 18, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.H.; Liu, B.; Ullman, S.; Jadback, I.; Engstrom, K. Children’s Quality of Life Based on the KIDSCREEN-27: Child Self-Report, Parent Ratings and Child-Parent Agreement in a Swedish Random Population Sample. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, T.L.; Zhang, T.; Thomas, K.T.; Zhang, X.; Gu, X. Predictive Strengths of Basic Psychological Needs in Physical Education Among Hispanic Children: A Gender-Based Approach. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2019, 38, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, L.D.; Allen, J.; Mulvenna, C.; Russell, P. An investigation of the relationships between the teaching climate, students’ perceived life skills development and well-being within physical education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2018, 23, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, S.R.; Taylor, I.M.; Meijen, C.; Passfield, L. Young adolescent psychological need profiles: Associations with classroom achievement and well-being. Psychol. Sch. 2019, 56, 1004–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erturan-Ilker, G. Psychological well-being and motivation in a Turkish physical education context. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2014, 30, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro-Suero, N.; Almagro, B.J.; Saenz-Lopez Bunuel, P. Psychological needs, motivation and emotional intelligence in Physical Education. Rev. Electron. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2019, 22, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, D.; Jimmefors, A.; Mousavi, F.; Adrianson, L.; Rosenberg, P.; Archer, T. Self-regulatory mode (locomotion and assessment), well-being (subjective and psychological), and exercise behavior (frequency and intensity) in relation to high school pupils’ academic achievement. PeerJ 2015, 3, e847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garn, A.C.; McCaughtry, N.; Martin, J.; Shen, B.; Fahlman, M. A Basic Needs Theory investigation of adolescents’ physical self-concept and global self-esteem. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 10, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Garcés de los Fayos, E.J.; García Dantas, A. Indicators of Psychological Well-Being Perceived by Physical Education Students. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2012, 21, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, A.S.; Lonsdale, C.; Lubans, D.R.; Ng, J.Y.Y. Increasing students’ physical activity during school physical education: Rationale and protocol for the SELF-FIT cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2017, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovoll, H.S.; Bentzen, M.; Safvenbom, R. Development of Positive Emotions in Physical Education: Person-Centred Approach for Understanding Motivational Stability and Change. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 64, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jančiauskas, R. Characteristics of young learners’ psychological well-being and self-esteem in physical education lessons. Baltic J. Sport Health Sci. 2012, 85, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karasimopoulou, S.; Derri, V.; Zervoudaki, E. Children’s perceptions about their health-related quality of life: Effects of a health education–social skills program. Health Educ. Res. 2012, 27, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madsen, M.; Elbe, A.; Madsen, E.E.; Ermidis, G.; Ryom, K.; Wikman, J.M.; Rasmussen Lind, R.; Larsen, M.N.; Krustrup, P. The “11 for Health in Denmark” intervention in 10- to 12-year-old Danish girls and boys and its effects on well-being—A large-scale cluster RCT. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDavid, L.; McDonough, M.H. Observed staff engagement predicts postive relationships and well-being in a physical activity-based program for low-income youth. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 49, 101705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neave, N.; Johnson, A.; Whelan, K.; McKenzie, K. The psychological benefits of circus skills training (CST) in schoolchildren. Theatre Danc. Perform. Train. 2020, 11, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, S.; O’Brien, C.; Faulkner, G.; Stone, M. Happiness in Motion: Emotions, Well-Being, and Active School Travel. J. Sch. Health 2014, 84, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.K.; Reinboth, M.S.; Resaland, G.K.; Bratland-Sanda, S. Changes in Physical Activity, Physical Fitness and Well-Being Following a School-Based Health Promotion Program in a Norwegian Region with a Poor Public Health Profile: A Non-Randomized Controlled Study in Early Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, J.J.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Faulkner, G.; Morgan, P.J.; Kennedy, S.G.; Lubans, D. Intervention effects and mediators of well-being in a school-based physical activity program for adolescents: The ‘Resistance Training for Teens’ cluster RCT. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Cumming, S.; Gillison, F. A cluster randomized controlled trial of the be the best you can be intervention: Effects on the psychological and physical well-being of school children. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do los Valadez, M.D.; Rodriguez-Naveiras, E.; Castellanos-Simons, D.; Lopez-Aymes, G.; Aguirre, T.; Flores, J.F.; Borges, A. Physical Activity and Well-Being of High Ability Students and Community Samples During the COVID-19 Health Alert. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 606167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozo, P.; Grao-Cruces, A.; Pérez-Ordás, R. Teaching personal and social responsibility model-based programmes in physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018, 24, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-Y.; Yi, K.J.; Walker, G.J.; Spence, J.C. Preferred Leisure Type, Value Orientations, and Psychological Well-Being Among East Asian Youth. Leis. Sci. 2017, 39, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noggle, J.J.; Steiner, N.J.; Minami, T.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Benefits of yoga for psychosocial well-being in a US high school curriculum: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatrics JDBP 2012, 33, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fattore, T.; Mason, J.; Watson, E. Children’s conceptualisation(s) of their well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 80, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Cadenas-Sánchez, C.; Estévez-López, F.; Muñoz, N.E.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Migueles, J.H.; Molina-García, P.; Henriksson, H.; Mena-Molina, A.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; et al. Role of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in the Mental Health of Preschoolers, Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. (Auckland N. Z.) 2019, 49, 1383–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakır, Y.; Kangalgil, M. The Effect of Sport on the Level of Positivity and Well-Being in Adolescents Engaged in Sport Regularly. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2017, 5, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kern, M.L.; Waters, L.E.; Adler, A.; White, M.A. A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breslin, G.; Shannon, S.; Fitzpatrick, B.; Hanna, D.; Belton, S.; Brennan, D. Physical Activity, Well-Being and Needs Satisfaction in Eight and Nine-Year-Old Children from Areas of Socio-Economic Disadvantage. Child Care Pract. 2017, 23, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slee, V.; Allan, J.F. Purposeful Outdoor Learning Empowers Children to Deal with School Transitions. Sports 2019, 7, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, M.D.; Yan Ho, W.K.; Zazed, K.; Van Niekerk, R.L.; Jong-Young Lee, L. The adolescent age transition and the impact of physical activity on perceptions of success, self-esteem and well-being. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2016, 16, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocca, A.; Verdugo, F.E.; Cuenca, L.T.R.; Cocca, M. Effect of a game-based physical education program on physical fitness and mental health in elementary school children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinboth, M.; Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. Dimensions of Coaching Behavior, Need Satisfaction, and the Psychological and Physical Welfare of Young Athletes. Motiv. Emot. 2004, 28, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Ryzin, M.J.; Gravely, A.A.; Roseth, C.J. Autonomy, Belongingness, and Engagement in School as Contributors to Adolescent Psychological Well-Being. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videon, T. Parent-Child Relations and Children’s Psychological Well-Being: Do Dads Matter? J. Fam. Issues 2005, 36, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, C.; Burrows, A.; McGrane, B. Health wearables in adolescents: Implications for body satisfaction, motivation and physical activity. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2019, 57, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamón, R.A.; García-Canto, E.; Pérez-Soto, J.J. Physical fitness and emotional well-being in school children aged 7 to 12 years. Acta Colomb. Psicol. 2018, 21, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R.; Emeljanovas, A. Self-perception of physical activity and fitness is related to lower psychosomatic health symptoms in adolescents with unhealthy lifestyles. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bunketorp Käll, L.; Malmgren, H.; Olsson, E.; Lindén, T.; Nilsson, M. Effects of a Curricular Physical Activity Intervention on Children’s School Performance, Wellness, and Brain Development. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lang, C.; Brand, S.; Colledge, F.; Ludyga, S.; Puhse, U.; Gerber, M. Adolescents’ personal beliefs about sufficient physical activity are more closely related to sleep and psychological functioning than self-reported physical activity: A prospective study. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado, J.R.; Fernández, Á.I.; López, J.M. Evaluación de la práctica de actividad física, la adherencia a la dieta y el comportamiento y su relación con la calidad de vida en estudiantes de Educación Primaria. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2020, 38, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, T.; Sharma, M. Physical activity among school-aged children and intervention programs using self-determination theory (SDT): A scoping review. J. Health Soc. Sci. 2020, 5, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, J.; Gómez-López, M.; Pérez-Turpin, J.A.; Muñoz-Villena, A.J.; Andreu-Cabrera, E. Perfectly Active Teenagers. When Does Physical Exercise Help Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garrido, R.R.; García, A.V.; Flores, J.L.P.; de Mier, R.J.R. Actividad físico deportiva, autoconcepto físico y bienestar psicológico en la adolescencia. Retos Nuevas Perspect. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2012, 22, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cervelló, E.; Peruyero, F.; Montero, C.; González-Cutre, D.; Beltrán-Carrillo, V.J.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A. Ejercicio, bienestar psicológico, calidad de sueño y motivación situacional en estudiantes de educación física. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2014, 14, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tudor, K.; Sarkar, M.; Spray, C. Exploring common stressors in physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gandía Delegido, B.; Soto-Rubio, M.; Soto-Rubio, A. Relación entre la práctica de actividad física y el rendimiento académico en escolares adolescentes. Calid. Vida Salud 2016, 9, 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hignett, A.; White, M.P.; Pahl, S.; Jenkin, R.; Froy, M.L. Evaluation of a surfing programme designed to increase personal well-being and connectedness to the natural environment among ‘at risk’ young people. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2018, 18, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDavid, L.; McDonough, M.H.; Blankenship, B.T.; LeBreton, J.M. A Test of Basic Psychological Needs Theory in a Physical-Activity-Based Program for Underserved Youth. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 39, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifers, S.; Shea, D. Evaluations of Girls on the Run/Girls on Track to Enhance Self-Esteem and Well-Being. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2013, 7, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulac, J.; Kristjansson, E.; Calhoun, M. ‘Bigger than hip-hop?’ Impact of a community-based physical activity program on youth living in a disadvantaged neighborhood in Canada. J. Youth Stud. 2011, 14, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.; Anicama, C.; Zhou, Q. Longitudinal relations among school context, school-based parent involvement, and academic achievement of Chinese American children in immigrant families. J. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 88, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, J. The effect of accumulated walking on the psychological well-being and on selected physical and physiological parameters of overweight/obese adolescents. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2015, 21, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Y.; Taghdisi, M.H.; Nourijelyani, K. Psychological Well-Being (PWB) of School Adolescents Aged 12–18 yr, its Correlation with General Levels of Physical Activity (PA) and Socio-Demographic Factors in Gilgit, Pakistan. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 804–813. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, M.K.; Quin, E.; Redding, E. dance 4 your life: Exploring the health and well-being implications of a contemporary dance intervention for female adolescents. Res. Danc. Educ. 2011, 12, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Construct |

|---|---|

| Ryff and Singer [39,40] | Self-acceptance |

| Positive relationships with others | |

| Personal growth | |

| Purpose in life | |

| Environmental mastery | |

| Autonomy | |

| Ryan and Deci [41,42] | Competence |

| Autonomy | |

| Relationships | |

| Warr [43] | Positive self-evaluation |

| Growth | |

| Learn through new experiences | |

| Realistic freedom from constraints | |

| Some degree of personal success in valued pursuits | |

| Bauer, McAdams and Pals [44] | Pleasure |

| Sense of meaning | |

| Higher degrees of psychosocial integration | |

| Personal growth | |

| Meaningful relationships | |

| Personal narratives and life stories involve growth and development | |

| Wissing and van Eeden [32] | Affect |

| Cognition | |

| Behavior | |

| Self-concept | |

| Interpersonal relationships | |

| No mental issues | |

| Bar-On [45] | Self-regard |

| Independence | |

| Problem solving | |

| Assertiveness | |

| Stress tolerance | |

| Self-actualization | |

| Happiness | |

| Reality-testing | |

| Interpersonal relationship | |

| Flexibility | |

| Social responsibility |

| Study | Journal | Objectives | Population/ Sample Size | Instruments Used to Assess Well-Being | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bagøien et al. [56] | Perceptual and Motor Skills | Test a trans-contextual model based on the self-determination theory of the relations among motivation in PE, motivation in leisure-time PA, PA and PW. | = 16.5) n = 329 | Support for perceived autonomy: Physical Education Climate Questionnaire (PECQ); BPN Satisfaction: Basic Psychological Need Scale—General; Autonomous Motivation: Self-Regulation Questionnaire; PA in leisure time and effort: ad hoc questionnaire. | There is an association between teacher support for autonomy in PE classes and student BPN satisfaction, which is related to autonomous motivation for participation in PE. Autonomous motivation is positively related to perceived competence and autonomous motivation during free time, which is also related to PW in general. |

| 2. Barth et al. [57] | Mental Health and PA | Describe the association among PA, mental health and academic achievement in adolescents. | = 13.3) n = 1001 (402♂ 599 ♀) | Accelerometer, grade point average. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being scale (WEMWBS) Harter’s Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (SPPA) and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The Family Affluence Scale (FAS) and academic achievement. | PA is positively associated with mental well- being, perceived competence and social acceptance. There is no association with self-esteem. No relations were found between PA and academic performance, but an association appeared between PA and performance in PE for women. |

| 3. Berman et al. [58] | Plos One | Provide self-report standards for children and parents for the KIDSCREEN-27 in Swedish children aged 11–16 years. | Children 11-16 years n = 1200 and one of their parents n = 600 | Children and adolescents’ quality of life (KIDSCREEN-27). Parental QoL (WHOQOL-Bref. and Sociodemographic factors. | The Swedish children in this sample score lower for PW (48.8 SE/49.94 EU), but higher for the other KIDSCREEN-27 dimensions: PW (53.4/49.77), Parent relations and autonomy (55.1/49.99), social support and peers (54.1/49.94) and school (55.8/50.01). Older children self-report lower well-being than younger children. No significant self-reported gender differences occur, and parent ratings show no gender or age differences. |

| 4. Chu et al. [59] | Journal of Teaching in Physical Education | Explore the predictive strengths and relative importance of BPN in PE in physical, cognitive and psychological outcomes in Hispanic boys and girls. | 4th and 5th grade children n = 214 (110♂ 104 ♀) | Demographic information. BPNs: autonomy (Standage scale, Duda, Ntoumanis 2005); competence (Intrinsic Motivation Inventory); relations (Acceptance subscale of Need for Relatedness Scale); cardiorespiratory health (PACER TEST); effort (Effort Scale of Intrinsic Motivation Scale); body composition (Health-O-Meter 500KL Digital Scale). | Competence as a predictor of effort and well-being in children. Social relationships only predict well-being in boys, and well-being and effort in girls. Autonomy does not predict any improvement. |

| 5. Cronin et al. [60] | PE and Sport Pedagogy | Explore the relationship between the teaching climate and students’ perceived development of LS in PE and their PW. | SE and young adults 11–18 years n = 294 (204 ♂ 90 ♀) | Support for autonomy: Sport Climate Questionnaire; LS development: Life Skill Scale. | Students perceive improvements in LS through PE: teamwork, goal setting, time management, emotional skills, interpersonal communication, social skills, leadership, and problem-solving and decision-making. Support for teacher autonomy is positively related to the perception of LS development in PE and its PW. |

| 6. Earl et al. [61] | Psychology in Schools | Identify satisfaction profiles of psychological needs (PN) and in grades in classroom performance, and self-reported well-being results. | SE students 11–15 years n = 586 (387♂ 199 ♀) | Autonomy satisfaction; competence: Perceived Competence subscale of the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory; relationships: Acceptance Subscale of Need for Relatedness Scale); teacher achievement; Subjective Vitality Scale; Perceived Stress Scale; Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. | Five profiles appear; four profiles indicate a synergy among three needs, showing similar in-group levels of satisfaction across needs, but in varying amounts. The findings illustrate that the three psychological needs may operate interdependently and should be considered together rather than isolated. |

| 7. Erturan-Ilker [62] | Educational Psychology in Practice | Examine the relationships among BPN, motivational regulations, self-esteem, subjective vitality and social physical anxiety in PE. | SE students 14–19 years n = 1082 (539♂ 543 ♀) | PN: Need Satisfaction Scale; motivation: Situational Regulation Scale. | Students’ motivational regulations mediate the relation between BPN and PW. Intrinsic motivation negatively predicts social physique anxiety and positively predicts subjective vitality. Amotivation positively predicts social physique anxiety and negatively predicts subjective vitality. The identified regulation and external regulation positively predicts subjective vitality. |

| 8. Fierro-Suero et al. [63] | Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado | Analyze the relationship among BPN, motivation, emotional intelligence, life satisfaction and academic performance in PE classes. | SE students 11–17 years n = 343 (161 ♂ 182 ♀) | BPN: BPN Measurement Scale; perceived locus of causality: Perceived Locus Scale of Causality in PE PLOC; emotional intelligence: Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire EQI: Young Version and the Life Satisfaction Scale. | The results show positive correlations among PNs, the most self-determined types of motivation, emotional intelligence and possible consequences, such as academic performance or life satisfaction. Demotivation is associated with lower levels in the study variables along the Self-Determination Theory lines. LBBs act as predictors of the most self-determined types of motivation and emotional intelligence. |

| 9. García et al. [64] | PeerJ | Investigate whether self-regulation, well-being and exercise behavior influence the academic performance of Swedish SE students. | Secondary Students ( = 17.7 years). n = 160 (111 ♂ 49 ♀) | Self-regulation: Regulatory Mode Questionnaire; subjective well-being: Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, Satisfaction with Life Scale; exercise behavior: 2 items to measure frequency of exercise practice; academic achievement: grades in mathematics, English and PE. | Academic achievement is positively related to assessment, well-being and frequent/intensive exercise behavior. Assessment is, however, negatively related to well-being. Locomotion is positively associated with well-being and also with exercise behavior. |

| 10. Garn et al. [65] | International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology | Test a BPN model of physical self-concept in SE teenagers. | High school students n = 1022 Mage = 16.13 (511♀ 490 ♂) | Autonomy support: Sport Climate Questionnaire; BPN Basic Need Satisfaction at Work Scale. | Need satisfaction fully mediates autonomy support and physical self-concept and autonomy support and global self-esteem. Physical self-concept is a partial mediator in the relationship between overall need satisfaction and global self-esteem. |

| 11. González et al. [66] | Journal of Sport Psychology | Establish relationships between educational styles on content transmission in PE classes and the PW perceived by students in PE. | Students 11–14 years n = 150 (64 ♂ 86 ♀) and PE teachers n = 15 | Educational styles: Styles Questionnaire Educational Profiles (PEE); the Spanish version of Ryff’s Scale of Psychological Well-Being. | The data analysis suggests a positive correspondence between the indices of psychological well-being perceived by students with the way in which their PE teachers teach this subject. |

| 12. Ha et al. [67] | BMC Public Health | Examine the effects of the intervention on students’ MVPA (moderate-to-vigorous physical activity) during PE. | = 14 n = 773 | AFMV: accelerometer; need for teacher support: The Learning Climate Questionnaire; BPN: Basic Need Satisfaction in Sport Scale; AF autonomous motivation: Perceive Locus Causality Questionnaire; future intention of sports practice: 2 items; health-related physical condition: Hong Kong School Physical Fitness Award Scheme; interviews and focus group. | The SELF-FIT intervention was designed to improve students’ health and well-being by using high-intensity activities in classes given by teachers trained in supportive autonomy needs. If successful, scalable interventions based on SELF-FIT can be applied to PE in general. |

| 13. Lovoll et al. [68] | Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research | Explore processes of developing emotional patterns in PE over a 3-year period in SE. | SE students 14–17 years n = 1681 (51% ♂ 49% ♀) | Basic Emotion State Scale. Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction in PE: BPNES; Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). | The results reveal an association among the intensity of positive emotions, BPN satisfaction and quality of motivation. |

| 14. Jančiauskas [69] | Baltic Journal of Sport and Health Sciences | Analyze the self-esteem and PW of young students in PE classes. | Students n = 222 | Self-esteem: Self-assessment scale; PW profiles formed based on A. Suslavičius semantic differential method. | The results show that 41% of the evaluated children have high PW levels, with the same percentage for those who consider their self-esteem to be average. |

| 15. Karasimopoulou et al. [70] | Health Education Research | Examine the effect of the Health Education Program “Skills for primary school Children” quality of life: physical well-being, mental well-being, moods, and emotions, self-concept, leisure-autonomy, family life, financial resources, friends, school environment, social acceptance (bullying). | Students 10–12 years n = 286 (139 ♂ 147 ♀) | KIDSCREEN-52 Group Europe. | The children in the experimental group have significantly improved perceptions of physical well-being, family life, financial aspects, friends, school life and social acceptance. The children in the control group have significantly improved perceptions of physical well-being, which deteriorate significantly for family life, mood and feelings and social acceptance. Children’s self-concept also improves. The experimental group has better autonomy perceptions than the control group. |

| 16. Madsen et al. [71] | Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports | Analyze the well-being effects for the 10- to 12-year-old children who participated in the school-based intervention “11 for Health in Denmark,” which comprises PA and health education. | Children aged 10–12 years n = 3061 | Brief scale of multidimensional well-being (KIDSCREEN-27). | The “11 for Health in Denmark” intervention program has a positive effect on girls’ physical well-being, whereas the improvement for boys is not significant. The program also positively impacts the well-being scores for peers and social support. When analyzed separately in the boys’ and girls’ subgroups, changes are not significant. |

| 17. McDavid and McDonough [72] | Psychology of Sports and Exercise | Examine associations between observed staff behaviors and youths’ perceptions of their relationships with staff and well-being. | Youth form PYD programs Staff n = 24, Youth n = 394 Mage = 10.20 (53%♂ 47% ♀) | Youth Program Quality Assessment (YPQA), Perception of Teachers Scale, Teacher Mutual Respect Scale, Learning Climate Questionnaire; social competence and self-worth: Self-Perception Profile for Children; Hope: Hope Scale. | Structural equation modeling indicates that the observed staff engagement positively predicts youths’ perceptions of their relationships with staff and well-being. Youths’ perceptions of positive social relationships with staff also positively predict their well-being. |

| 18. Neave et al. [73] | Theater, Dance and Performance Training | Assess the effectiveness of engaging in CST (Circus Skills Training) for up to 6 months on the development and enhancement of a range of physical, psychological and emotional measures in children aged 9–12. | Children 9–12 years n = 89 | Optimism−pessimism: ‘Youth Life Orientation Test’ (YLOT), AF: PAQ-C; prosocial behaviors: ‘Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire’ (SDQ) | With an intersubject design, two groups of children (aged 9–12 years) are compared at the baseline by various physical and psychological well-being measures. Significant differences appear between the children in the experimental group vs. the control group. |

| 19. Ramanathan et al. [74] | Journal of School Health | Analyze the association between active transport to school and indicators of happiness and well-being of Canadian children and their parents. | Students n = 5423 (mostly in kindergarten to grade 8) Parents n = 5423 | Demographic variables and distances to travel to school survey; emotional perception of the way to travel to school: 2 items. Welfare of active transport: 4 items. | Parents and children using active transport report increased positive emotions. Parents who actively travel with their children report stronger connections to well-being dimensions. Active transport shows the strongest association with parents’ perceptions of their child’s well-being. Positive emotions (parent and child) are also significantly related to well-being on trips to school. |

| 20. Schmidt et al. [75] | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | Examine changes in PA, physical fitness and PW in early adolescents after implementing a school-based health promotion program in SE schools. | Students 13–15 years n = 813 | Subjective vitality and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in five domains: physical health, psychological well-being, parent, peers and school. PA and sedentary lifestyle: accelerometer; cardiorespiratory fitness: Andersen test; strength: standing long jump test; anthropometry, demographics; | A multicomponent school program emphasizes the use of active physical learning with positive changes in school-based PA levels. Positive changes are seen in young adolescents’ physical fitness, vitality and health-related quality of life. |

| 21. Smith et al. [76] | Mental Health and Physical Activity | Examine the impact of a school-based PA intervention on adolescents’ self-esteem and subjective well-being, and explore the moderators and mediators of intervention effects. | 9th grade scholars n = 607 49.6% (♀) | global self-esteem: Physical Self-Description Questionnaire (PSDQ); socio-economic status: Socio-Economic Indices for Areas (SEIFA), weight, height and BMI; physical self-perception: International Fitness Scale (IFIS); self-efficacy to training: Luban’s Scale; autonomous Motivation: BREQ-2. | Intervention effects for self-esteem and well-being are not statistically significant. Moderator analyses show that the effects for self-esteem are stronger for the overweight/obese subgroup, and resistance training self-efficacy is a significant mediator of changes in self-esteem. No other significant indirect effects are observed. |

| 22. Standage et al. [77] | BMC Public Health | Determine the effectiveness of the BtBYCB program ‘Be the Best You Can Be’ on (i) pupils’ well-being, self-perceptions, self-esteem, aspirations, and learning strategies; (ii) changes in modifiable health-risk behaviors (i.e., PA, diet, smoking, alcohol consumption). | Students 11–13 years n = 711 | Self-esteem: Rosenberg Scale; adaptive learning strategies: Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scale; AF: Physical Activity for Older Children and Adolescents Questionnaire; alcohol and cigarettes: Youth Risk Behavior Survey; muscle mass: BMI; focus group. | This research informs about improvements in the BtBYCB program and other interventions that target child/youth health and wellness. |

| 23. Valadez et al. [78] | Frontiers in Psychology | Compare the perceptions and opinions of parents or caregivers of a community sample of children and adolescents to another with high abilities for PW, PA and sedentary lifestyles developed during the COVID-19 health crisis. | Parents Mage = 41.54 high-ability children n = 325 and parents control group n = 209 | Ad hoc questionnaire to evaluate: demographic data, pandemic problems, PA, routines, PA assessment by your child. | The results show no differences between students from community samples and those with high capacities in well-being and PA. Parents living in Spain observe less play time in the high-ability sample, and more time spent on homework, but make a high-ability diagnosis. |

| Study | Program Description | Number of Participants | JCR | PW Assessment | Methodology Description | PW Definition | Total Score | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bagøien et al. [56] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 | HQ |

| 2. Barth et al. [57] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 9 | HQ |

| 3. Berman et al. [58] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 11 | HQ |

| 4. Chu et al. [59] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 10 | HQ |

| 5. Cronin et al. [60] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 | HQ |

| 6. Earl et al. [61] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | HQ |

| 7. Erturan-Ilker [62] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 11 | HQ |

| 8. Fierro-Suero et al. [63] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 7 | MQ |

| 9. García et al. [64] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | HQ |

| 10. Garn et al. [65] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 9 | HQ |

| 11. González et al. [66] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 9 | HQ |

| 12. Ha et al. [67] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 11 | HQ |

| 13. Lovoll et al. [68] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 11 | HQ |

| 14. Jančiauskas [69] | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 | MQ |

| 15. Karasimopoulou et al. [70] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 10 | HQ |

| 16. Madsen et al. [71] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 9 | MQ |

| 17. McDavid and McDonough [72] | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | MQ |

| 18. Neave et al. [73] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | MQ |

| 19. Ramanathan et al. [74] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 9 | HQ |

| 20. Schmidt et al. [75] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 11 | HQ |

| 21. Smith et al. [76] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 12 | HQ |

| 22. Standage et al. [77] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 12 | HQ |

| 23. Valadez et al. [78] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 11 | HQ |

| Study Objectives for Students | Number of Mentions | Research Number |

|---|---|---|

| PA | 9 | 1, 2, 4, 12, 16, 20, 21, 23 |

| Mood/emotion states | 9 | 3, 4, 7, 13, 15, 18, 19, 22 |

| BPN | 8 | 1, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13 |

| Health | 8 | 2, 3, 4, 6, 12, 16, 22 |

| Self-perception | 6 | 2, 3, 15, 17, 22 |

| Motivation | 6 | 1, 8, 7, 12, 13, 21 |

| Program’s effectiveness | 5 | 3, 15, 16, 18, 22 |

| General well-being | 5 | 3, 11, 15, 19, 23 |

| Self-esteem | 4 | 7, 14, 21, 22 |

| Academic performance | 4 | 2, 6, 8, 9 |

| Autonomy | 4 | 3, 15, 22 |

| Social support | 3 | 3, 15, 16 |

| Economic resources | 3 | 3, 15, |

| Physical well-being | 3 | 3, 15, 16 |

| School environment | 3 | 2, 15, 16 |

| Teaching climate | 2 | 5, 10 |

| Life satisfaction | 2 | 8 |

| Vitality | 2 | 7 |

| Quality of life | 2 | 15, 20 |

| Prosocial behaviors | 2 | 17, 18 |

| Locus of control | 2 | 8, 12 |

| Anthropometry | 2 | 20, 21 |

| Life skills | 1 | 5 |

| Self-regulation | 1 | 9 |

| Aspirations | 1 | 22 |

| Learning strategies | 1 | 22 |

| Emotional intelligence | 1 | 8 |

| Happiness | 1 | 19 |

| Active transport | 1 | 19 |

| Teacher achievement | 1 | 6 |

| Social physical anxiety | 1 | 7 |

| Need for teacher support | 1 | 12 |

| Future PA practice intentions | 1 | 12 |

| Hope | 1 | 17 |

| Self-efficacy in PA | 1 | 21 |

| Sedentary lifestyles | 1 | 23 |

| Study objectives for teachers | Number of mentions | Research number |

| Educational styles | 1 | 11 |

| Social relationships | 1 | 17 |

| Study objectives for parents | Number of mentions | Research number |

| Happiness | 1 | 19 |

| Well-being | 1 | 19 |

| Active Transport | 1 | 19 |

| Quality of Life | 1 | 3 |

| Research | Well-Being Variable | Other Types of Variables |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Bagøien et al. [56] | BPN Well-being | PE motivation Leisure PA |

| 2. Barth et al. [57] | Well-being Self-Perception | PA Academic achievement |

| 3. Berman et al. [58] | PW Mood state Self-perception Autonomy Friendships and social support | Physical wellness Parents’ relationships and family life, school context Economic resources, parents’ quality of life |

| 4. Chu et al. [59] | BPN | Motivation Health Body composition |

| 5. Cronin et al. [60] | Life skills | PE teaching climate |

| 6. Earl et al. [61] | BPN Vitality | Academic performance Teacher’s achievement, academic stress Negative affects |

| 7. Erturan-Ilker [62] | BPN Self-esteem Subjective vitality | Motivation Social physique anxiety |

| 8. Fierro-Suero et al. [63] | BPN Life satisfaction Emotional intelligence | Motivation Academic performance Locus of control |

| 9. García et al., 2015 [64] | Self-regulation Subjective well-being Life satisfaction | Academic PE practice frequency |

| 10. Garn et al. [65] | BPN Self-concept | PE teaching climate |

| 11. González et al. [66]) | PW | Teacher’s education style |

| 12. Ha et al. [67] | BPN | MVPA Teacher’s support needs PA motivation Locus of control PA future practice intention Physical condition |

| 13. Lovoll et al. [68] | BPN | PE emotional patterns Motivation |

| 14. Jančiauskas [69] | BP Self-esteem | Satisfaction with PE classes |

| 15. Karasimopoulou et al. [70] | Psychological well-being Mood Self-perception Autonomy Friends and social support | Physical well-being effectiveness program Parents’ relationships and family life School context and economic resources |

| 16. Madsen et al. [71] | Psychological well-being Peers and social support | Physical well-being effectiveness program School environment |

| 17. McDavid and McDonough [72] | Well-being Self-perception Hope | Social relationships with staff |

| 18. Neave et al. [73] | Optimism and pessimism Prosocial behaviors | Effectiveness of a PE program |

| 19. Ramanathan et al. [74] | Happiness Well-being | Active transport |

| 20. Schmidt et al. [75] | Quality of life | Physical condition anthropometry |

| 21. Smith et al. [76] | Well-being Self-esteem | Physical condition anthropometry Self-efficacy in training Autonomous motivation |

| 22. Standage et al. [77] | Well-being Self-perception Self-esteem Acceptance | Effectiveness of a PE program Student learning strategies Changes in risky behaviors |

| 23. Valadez et al. [78] | Well-being | PA Sedentary lifestyles |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Ordás, R.; Piñeiro-Cossio, J.; Díaz-Chica, Ó.; Ayllón-Negrillo, E. Relevant Variables in the Stimulation of Psychological Well-Being in Physical Education: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159231

Pérez-Ordás R, Piñeiro-Cossio J, Díaz-Chica Ó, Ayllón-Negrillo E. Relevant Variables in the Stimulation of Psychological Well-Being in Physical Education: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159231

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Ordás, Raquel, Javier Piñeiro-Cossio, Óscar Díaz-Chica, and Ester Ayllón-Negrillo. 2022. "Relevant Variables in the Stimulation of Psychological Well-Being in Physical Education: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159231