Social Perception of Riparian Forests

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Public Survey

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

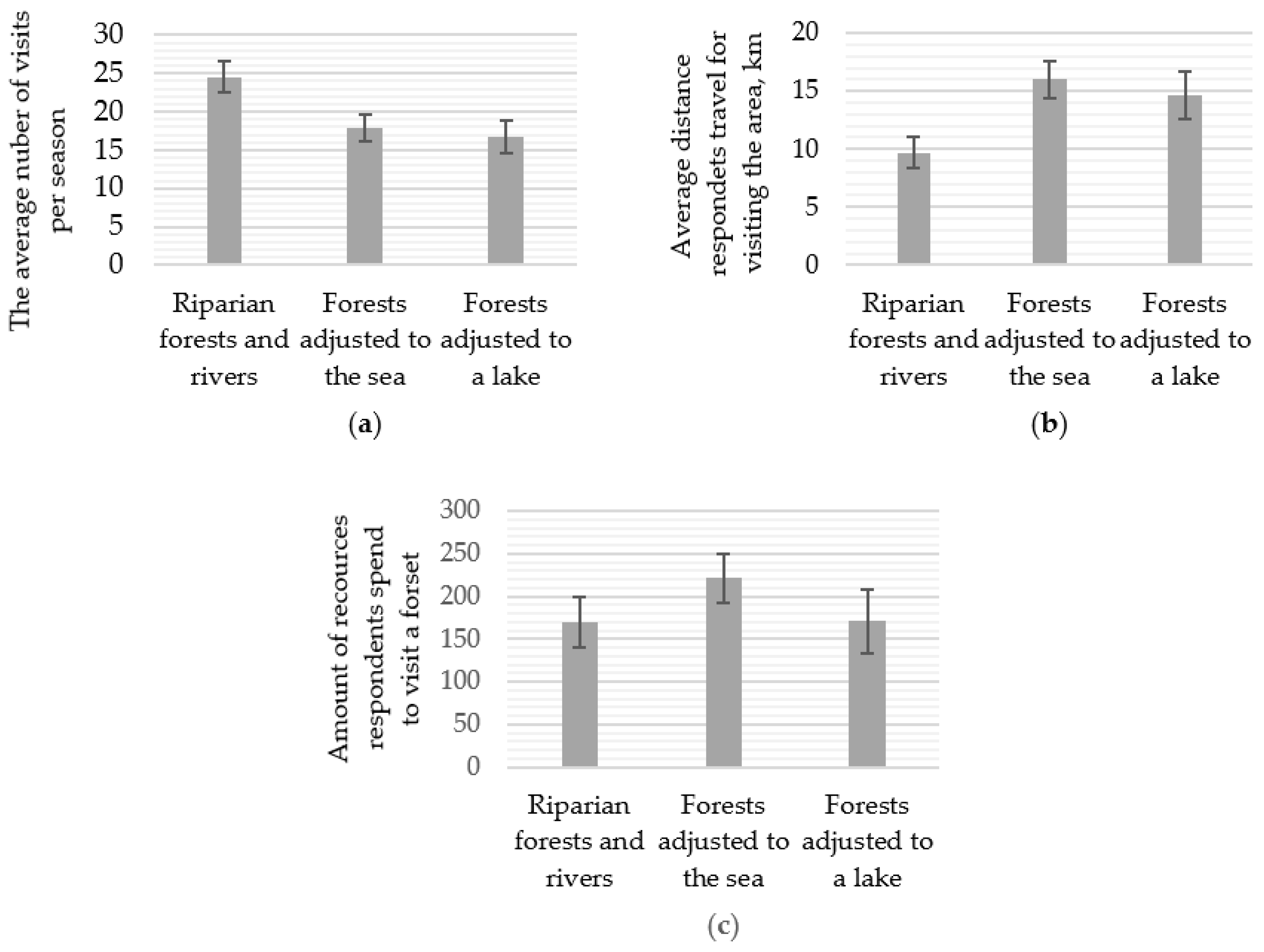

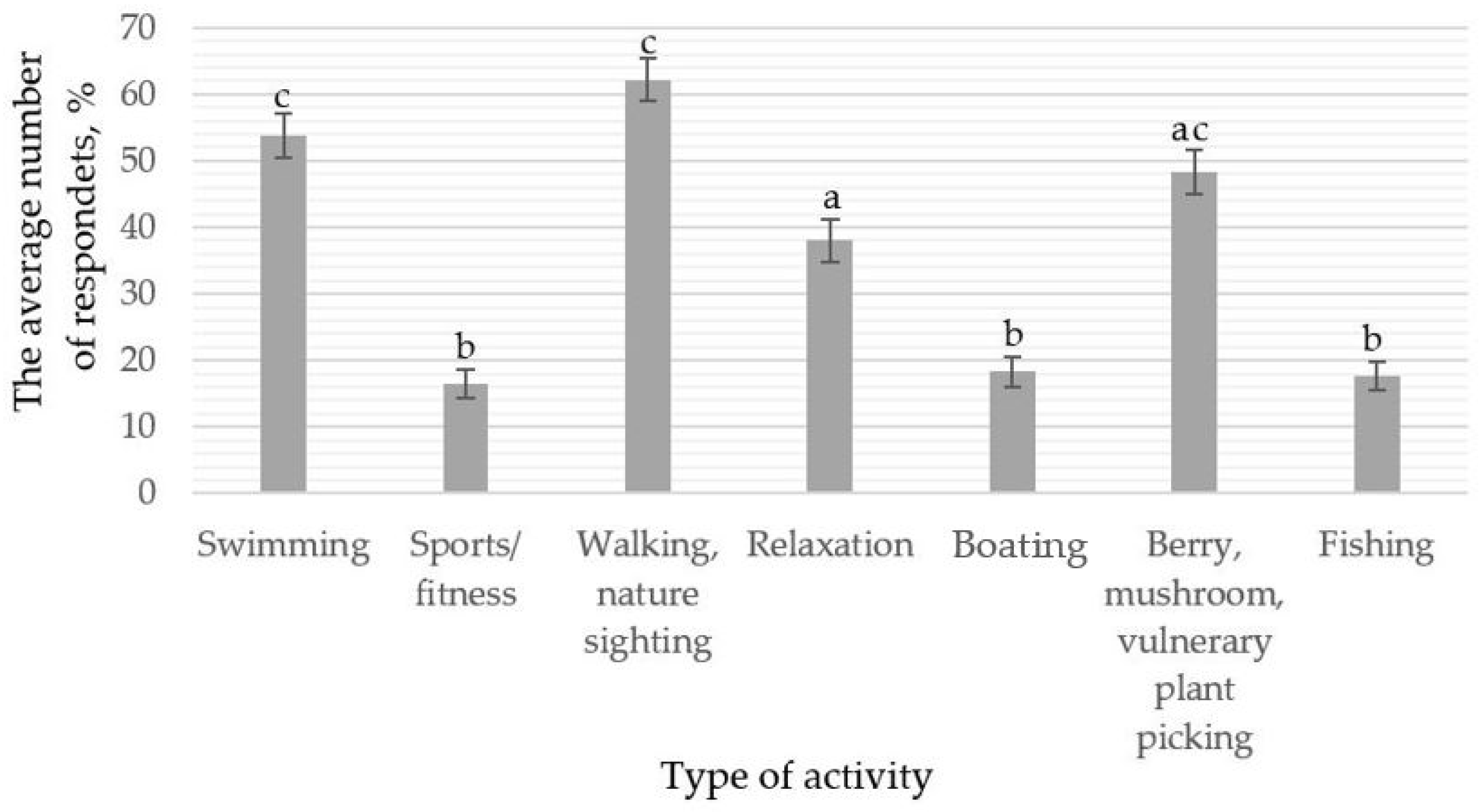

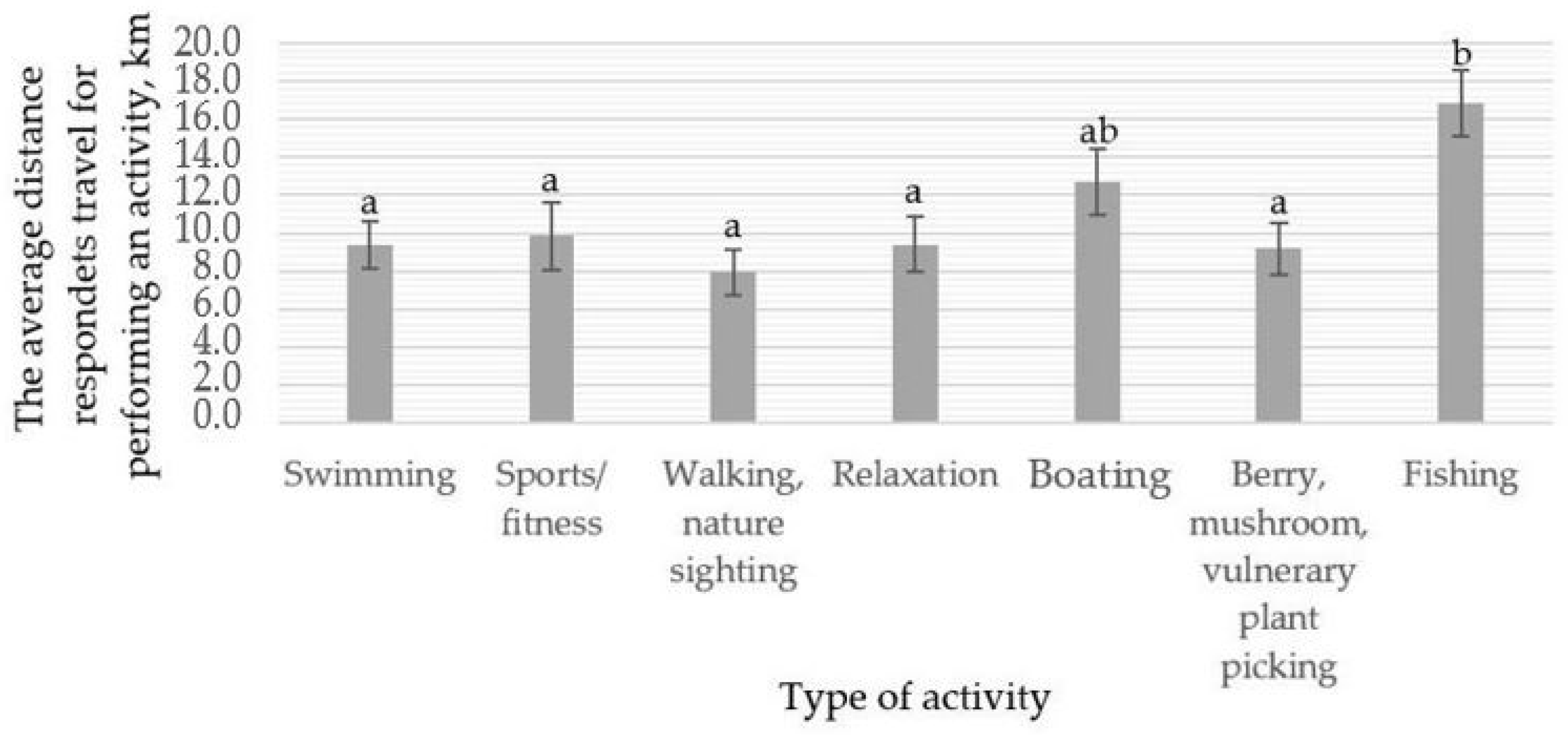

3.1. Recreational Habits and Frequency

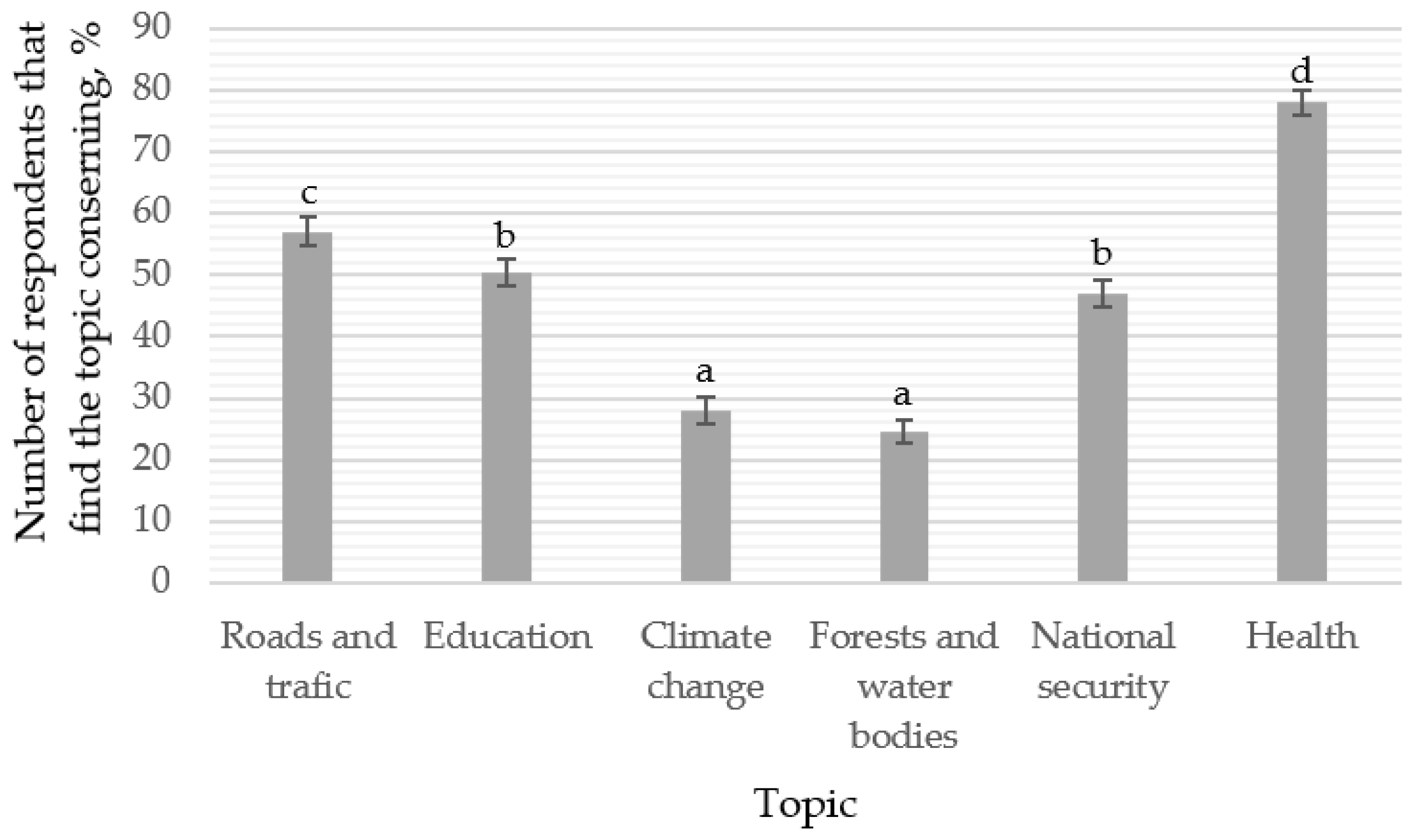

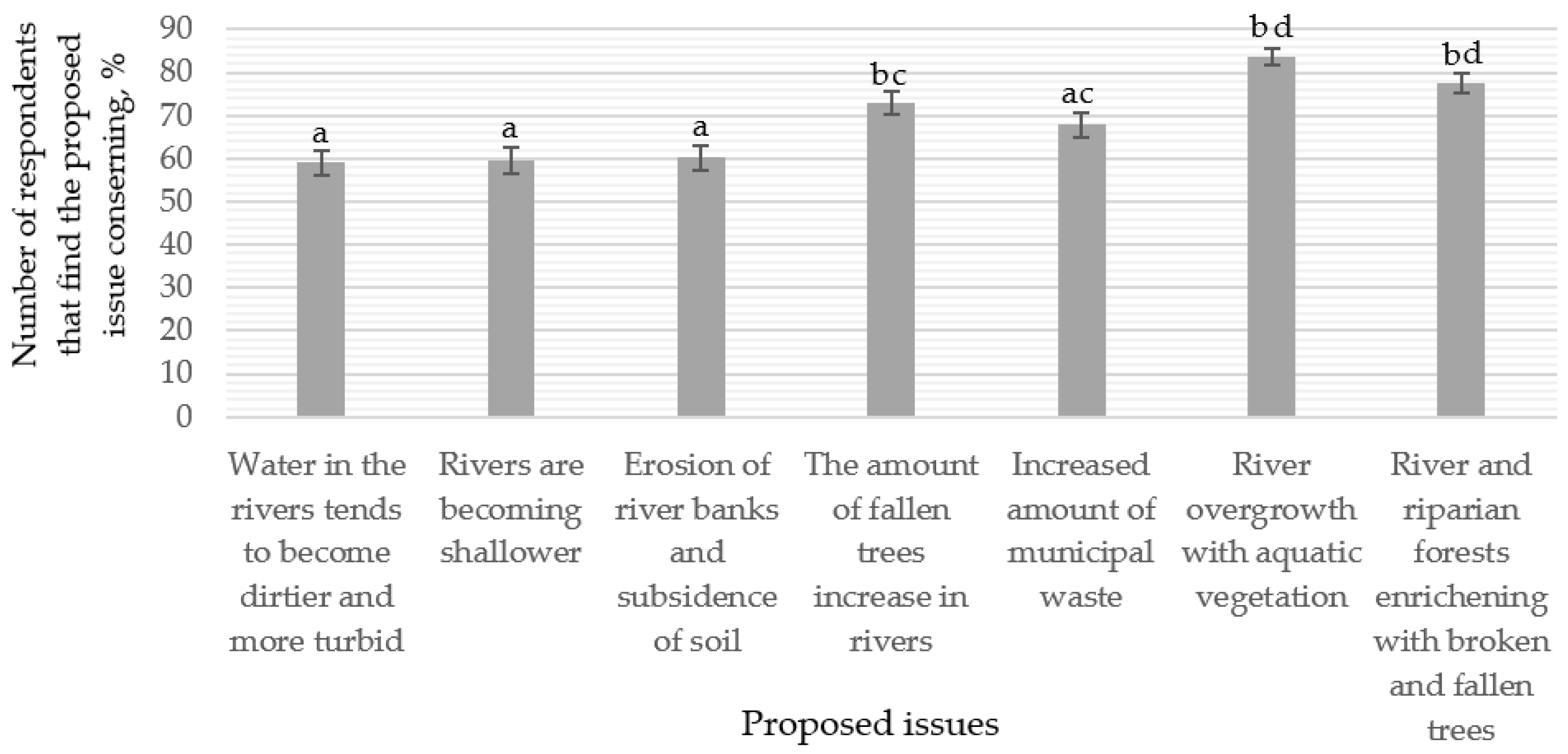

3.2. Public Concerns of Riverine Forests and Rivers

4. Discussion

4.1. Recreational Habits and Frequency

4.2. Public Concerns of Riverine Forests and Rivers

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ring, E.; Andersson, E.; Armolaitis, K.; Eklöf, K.; Finér, L.; Gil, W.; Glazko, Z.; Janek, M.; Lībiete, Z.; Lode, E.; et al. Good Practices for Forest Buffers to Improve Surface Water Quality in the Baltic Sea Region. (God Praxis för Kantzoner i Syfte att Förbättra Ytvattenkvalitet i Östersjöregionen). 2018. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-326-576-9 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Dufour, S.; Piégay, H. From the myth of a lost paradise to targeted river restoration: Forget natural references and focus on human benefits. River Res. Appl. 2009, 25, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riis, T.; Kelly-Quinn, M.; Aguiar, F.C.; Manolaki, P.; Bruno, D.; Bejarano, M.D.; Clerici, N.; Fernandes, M.R.; Franco, J.C.; Pettit, N.; et al. Global overview of ecosystem services provided by riparian vegetation. BioScience 2020, 70, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, E.; Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Bourgeois, B.; Boz, B.; Nilsson, C.; Palmer, G.; Sher, A.A. Integrative conservation of riparian zones. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 211, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, S.H.; Luckai, N.J.; Burke, J.M.; Prepas, E.E. Riparian areas in the Canadian boreal forest and linkages with water quality in streams. Environ. Rev. 2007, 15, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, E.S.; Blaszczak, J.R.; Ficken, C.D.; Fork, M.L.; Kaiser, K.E.; Seybold, E.C. Control Points in Ecosystems: Moving Beyond the Hot Spot Hot Moment Concept. Ecosystems 2017, 20, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, J.; Elbrecht, V.; Steinke, D.; Aroviita, J. Riparian forests can mitigate warming and ecological degradation of agricultural headwater streams. Freshw. Biol. 2021, 66, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.W.; Heck, K.L.; Able, K.W.; Childers, D.L.; Eggleston, D.B.; Gillanders, B.M.; Halpern, B.; Hays, C.G.; Hoshino, K.; Minello, T.J.; et al. The identification, conservation, and management of estuarine and marine nurseries for fish and invertebrates: A better understanding of the habitats that serve as nurseries for marine species and the factors that create site-specific variability in nursery quality will improve conservation and management of these areas. BioScience 2001, 51, 633–641. [Google Scholar]

- Capon, S.J.; Pettit, N.E. Turquoise is the new green: Restoring and enhancing riparian function in the Anthropocene. In Ecological Management and Restoration; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; Volume 19, pp. 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, S.; Rodríguez-González, P.M.; Laslier, M. Tracing the scientific trajectory of riparian vegetation studies: Main topics, approaches and needs in a globally changing world. In Science of the Total Environment; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 653, pp. 1168–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poff, B.; Koestner, K.A.; Neary, D.G.; Henderson, V. Threats to riparian ecosystems in Western North America: An analysis of existing literature. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2011, 47, 1241–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdahl, E.; Demps, K.; Heath, J.A. Decreased cortisol among hikers who preferentially visit and value biodiverse riparian zones. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandas, V. An empirical study of streamside landowners’ interest in riparian conservation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2007, 73, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingraff-Hamed, A.; George, F.N.; Lupp, G.; Pauleit, S. Effects of recreational use on restored urban floodplain vegetation in urban areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 67, 127444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizzetti, B.; Pistocchi, A.; Liquete, C.; Udias, A.; Bouraoui, F.; van de Bund, W. Human pressures and eco-logical status of European rivers. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Turunen, J.; Markkula, J.; Rajakallio, M.; Aroviita, J. Riparian forests mitigate harmful ecological effects of agricultural diffuse pollution in medium-sized streams. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolkkinen, M.; Vaarala, S.; Aroviita, J. The Importance of Riparian Forest Cover to the Ecological Status of Agricultural Streams in a Nationwide Assessment. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 35, 4009–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher Hasselquist, E.; Kuglerová, L.; Sjögren, J.; Hjältén, J.; Ring, E.; Sponseller, R.A.; Andersson, E.; Lundström, J.; Mancheva, I.; Nordin, A.; et al. Moving towards multi-layered, mixed-species forests in riparian buffers will enhance their long-term function in boreal landscapes. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 493, 119254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protection Zone Law. Published in the Official Publication “Latvijas Vēstnesis”, 25.02.1997, No. 56/57 (771/772). 5 February 1997. Available online: https://www.vestnesis.lv/ta/id/42348-aizsargjoslu-likums (accessed on 12 February 2022). (In Latvian).

- Sonesson, J.; Ring, E.; Högbom, L.; Lämås, T.; Widenfalk, O.; Mohtashami, S.; Holmström, H. Costs and benefits of seven alternatives for riparian forest buffer management. Scand. J. For. Res. 2021, 36, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Thor, G.; Low, M.; Sjögren, J.; Lindberg, E.; Eggers, S. What is good for birds is not always good for lichens: Interactions between forest structure and species richness in managed boreal forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 473, 118327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, D.E.L.; Raudsepp-Hearne, C.; Bennett, E.M. Effects of land use, cover, and protection on stream and riparian ecosystem services and biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Staats, H. The need for psychological restoration as a determinant of environmental preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donis, J.; Straupe, I. The assessment of contribution of forest plant non-wood products in Latvia’s national economy. In Proceedings of the Annual 17th International Scientific Conference Proceedings, Research for Rural Development 2011, Jelgava, Latvia, 18–20 May 2011; Latvia University of Agriculture: Jelgava, Latvia, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Donis, J. Rekreācijas preferences dažādos gadalaikos. [Recreational preferences in different seasons]. In Report on Research Programme “The Impact of Forest Management on Ecosystem Services Provided by Forests and Related Ecosystems” Results in 2017; Salaspils, Latvia, 2018; 243p, Available online: https://193.166.24.146/pdf/article10341.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Bārdule, A.; Jūrmalis, E.; Lībiete, Z.; Pauliņa, I.; Donis, J.; Treimane, A. Use of retail market data to assess prices and flows of non-wood forest products in Latvia. Silva Fenn. 2020, 54, 10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Fialova, J.; Tomusiak, R.; Woźnicka, M.; Prochazkova, P. Running as a form of recreation in the Polish and Czech forests-advantages and disadvantages. Sylwan 2019, 163, 522–528. [Google Scholar]

- Thiele, J.; Albert, C.; Hermes, J.; von Haaren, C. Assessing and quantifying offered cultural ecosystem services of German river landscapes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.E.; Vimercati, G.; Ferrini, S.; Shackleton, R.T. Perceptions of ecosystem services and disservices associated with open water swimming. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 37, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beil, K.; Hanes, D. The influence of urban natural and built environments on physiological and psychological measures of stress—A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 1250–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Lanki, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T. The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernest, B.; Emilia, J.; Norimasa, T.; Alicja, S.; Natalia, K.; Anna, Z.; Lidia, B. A view of waste might decrease relaxation: The effects of viewing an open dump in a forest environment on the psychological response of healthy young adults. BioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielinis, E.; Janeczko, E.; Janeczko, K.; Bielinis, L. Effect of an Illegal Open Dump in an Urban Forest on Landscape Appreciation. Preprint 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V.; Helge Frivold, L. Naturally dead and downed wood in Norwegian boreal forests: Public preferences and the effect of information. Scand. J. For. Res. 2011, 26, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovska, I.; Straupe, I.; Brumelis, G.; Donis, J.; Kupfere, L. Urban forests of Riga, Latvia-Pressures, naturalness, attitudes and management. Balt. For. 2014, 20, 342–351. [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen, V.; Stange, E.E.; Kaltenborn, B.P.; Vistad, O.I. Public visual preferences for dead wood in natural boreal forests: The effects of added information. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Bielinis, E.; Tiarasari, U.; Woźnicka, M.; Kędziora, W.; Przygodzki, S.; Janeczko, K. How dead wood in the forest decreases relaxation? the effects of viewing of dead wood in the forest environment on psychological responses of young adults. Forests 2021, 12, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korcz, N.; Janeczko, E. Forest Education with the Use of Educational Infrastructure in the Opinion of the Public-Experience from Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saklaurs, M.; Liepiņa, A.A.; Elferts, D.; Jansons, Ā. Social Perception of Riparian Forests. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159302

Saklaurs M, Liepiņa AA, Elferts D, Jansons Ā. Social Perception of Riparian Forests. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159302

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaklaurs, Mārcis, Agnese Anta Liepiņa, Didzis Elferts, and Āris Jansons. 2022. "Social Perception of Riparian Forests" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159302

APA StyleSaklaurs, M., Liepiņa, A. A., Elferts, D., & Jansons, Ā. (2022). Social Perception of Riparian Forests. Sustainability, 14(15), 9302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159302