Urban Waterfront Development, through the Lens of the Kyrenia Waterfront Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Potential of Water and Urban Waterfront

2.2. Definition of the Urban Waterfront

2.3. Principles of Urban Waterfront Development

2.3.1. Physical Quality

2.3.2. Functional Aspects

- Necessary activities are activities that are essential for daily life and need to be performed in practically all circumstances;

- Optional activities: These include taking a walk, standing around, or simply sitting and enjoying life. They occur when the external physical conditions are ideal. They are, however, enhanced in high-quality environments and drastically diminished in low-quality environments;

- Social activities: These rely on the presence of people in public settings. They include activities such as children playing, chatting in the street, and meeting friends in a park—in other words, a variety of communal activities.

- Water-dependent uses are those that rely on the presence of an urban waterfront to function. Without the urban waterfront, the building would not be able to function. Marinas, jetties, boathouses, and a water-taxi station are all examples of these types of architectural usage;

- Water-related uses are building applications that will benefit from the proximity to water but can also function in other areas. Restaurants, open spaces, parks, terraces, and resorts or hotels are all examples of these types of structures or projects;

- Water-independent uses refer to structures that can function equally effectively without access to water, in other parts of the city. Shop houses or shopping complexes, offices, workshops, mosques, residential areas, schools, and clinics are examples of this group of concerns.

2.3.3. Social Factors

2.3.4. Economic Facets

2.3.5. Cultural Features

2.3.6. Political Issues

2.4. Overall Summary

| Functional | The waterfront has various functional opportunities. |

| The waterfront is providing joyful areas with music, food, literature, dance, and/or maritime heritage. | |

| Different types of water-based activities can be seen. | |

| Physical | The waterfront is well maintained. |

| The place has presented various art objects in good physical condition. | |

| Urban furniture is in good physical condition. | |

| A certain level of mobility has been attained. The waterfront is accessible for persons with disabilities as well as those without. | |

| The area has access to other public environments. | |

| It is easy to reach the waterfront via pedestrian access, bicycle lanes, and/or public transportation. | |

| Traffic and parking condition is proper. | |

| Social | The environment is attractive. |

| As an observer, people with different education levels, age groups, ethnicities, and income levels can enjoy the place. | |

| As a user, I am proud to have such a place in the city. | |

| Economic | The economic and nature-friendly design approach was considered during the regeneration process. |

| The area provides good economic income. | |

| I like to visit here frequently. | |

| Cultural | Historical references are protected and/or reflected on the waterfront. |

| There are cultural and art activities in the place. | |

| The unique image has been protected and the image has developed. | |

| Politic | The regeneration process has been done with a successful cooperation process with related stakeholders. |

| Creativity, innovation, and/or social well-being policies are well-considered during the regeneration process. | |

| I feel that proper regulations have been created by politicians to provide continuous maintenance. |

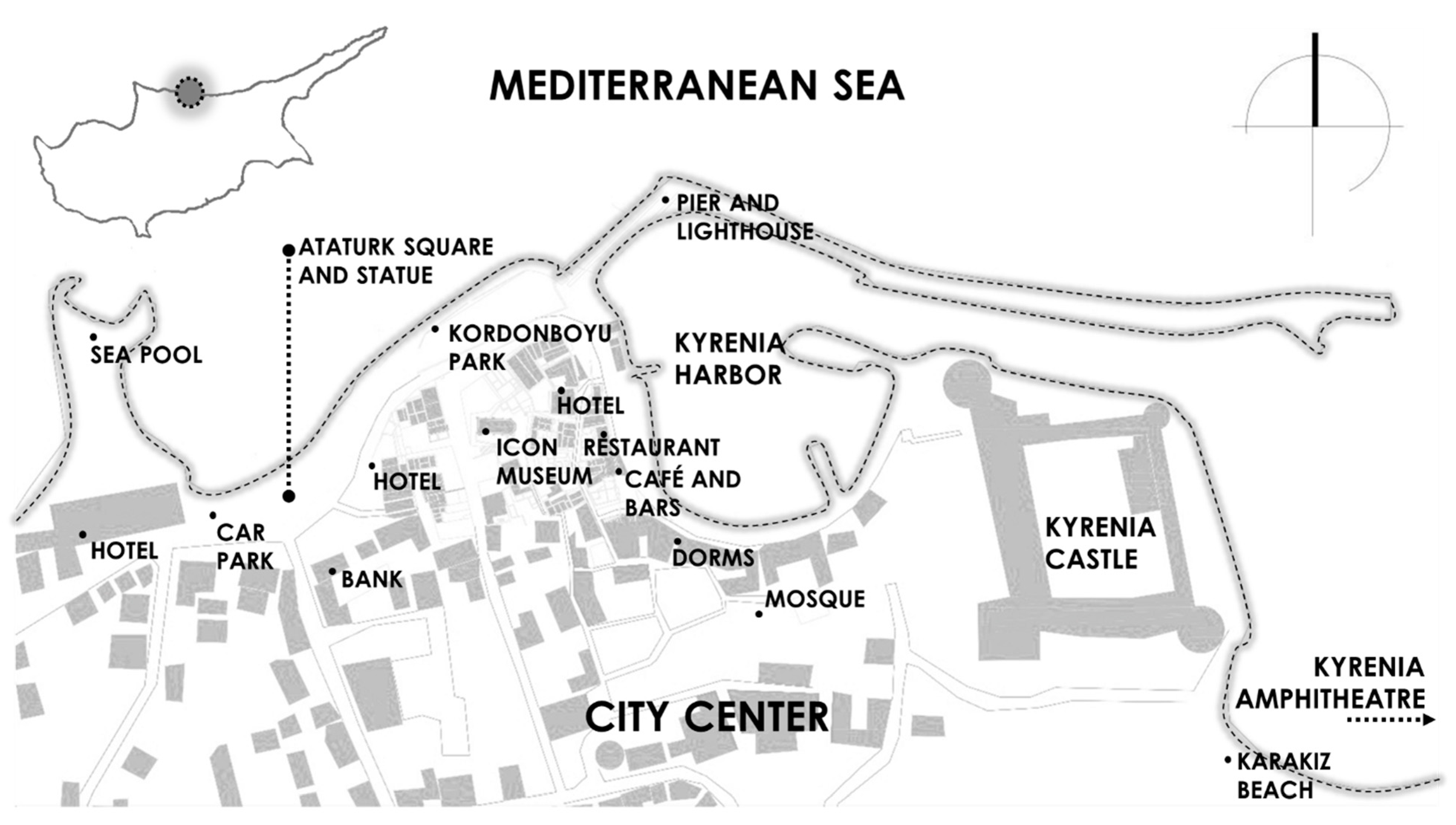

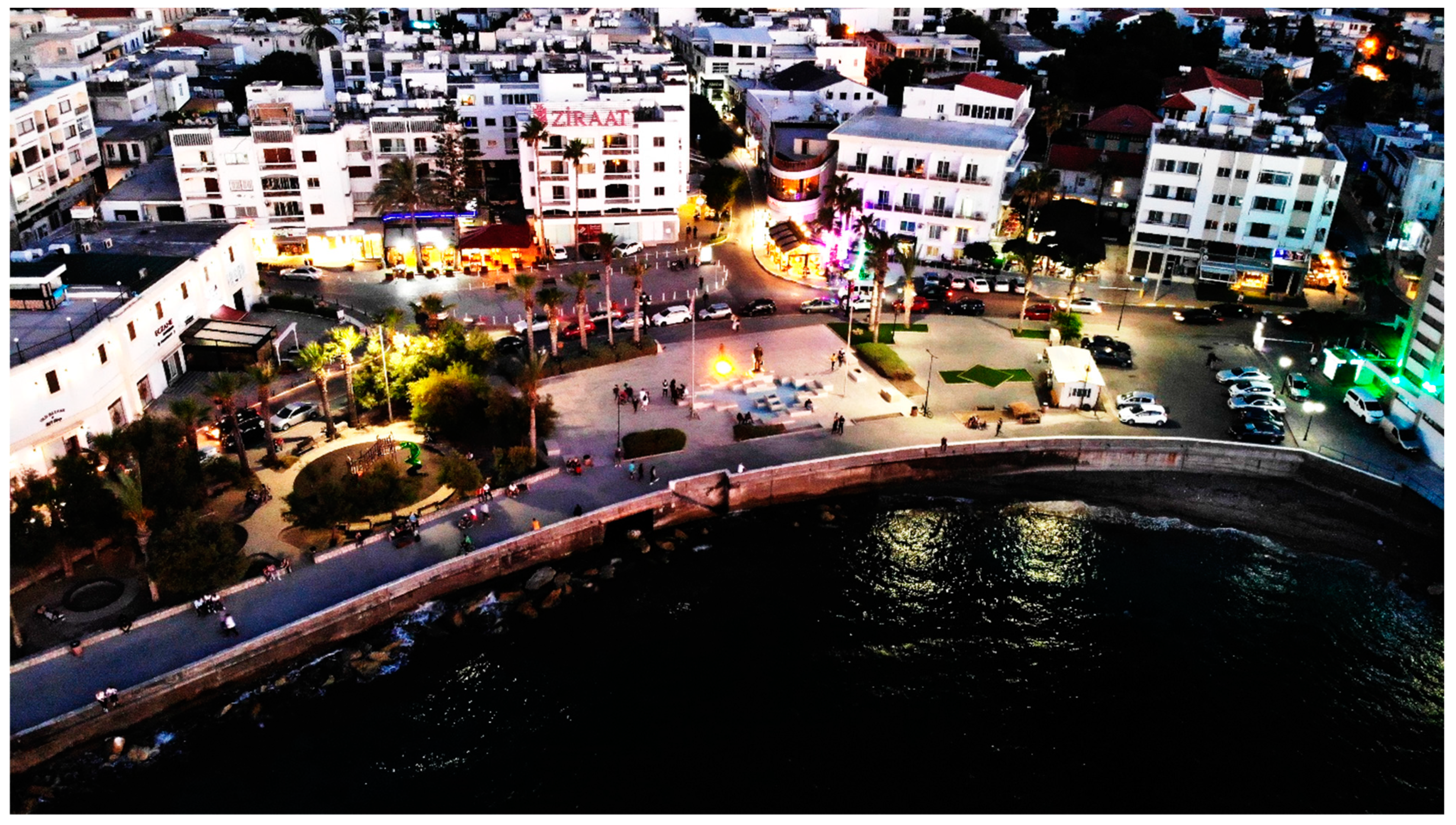

2.5. An Overview on Kyrenia Waterfront and Method of the Study

- Providing alternative parking for vehicles by allocating or establishing accessible parking spaces and access aisles;

- Displaying signs for vehicles to ensure pedestrian safety;

- Installing signs for vehicles to ensure the safety of pedestrians;

- Establishing routine maintenance and increasing its frequency;

- Restroom renovations in public spaces;

- Various parking laws to facilitate pedestrian mobility.

3. Materials and Methods

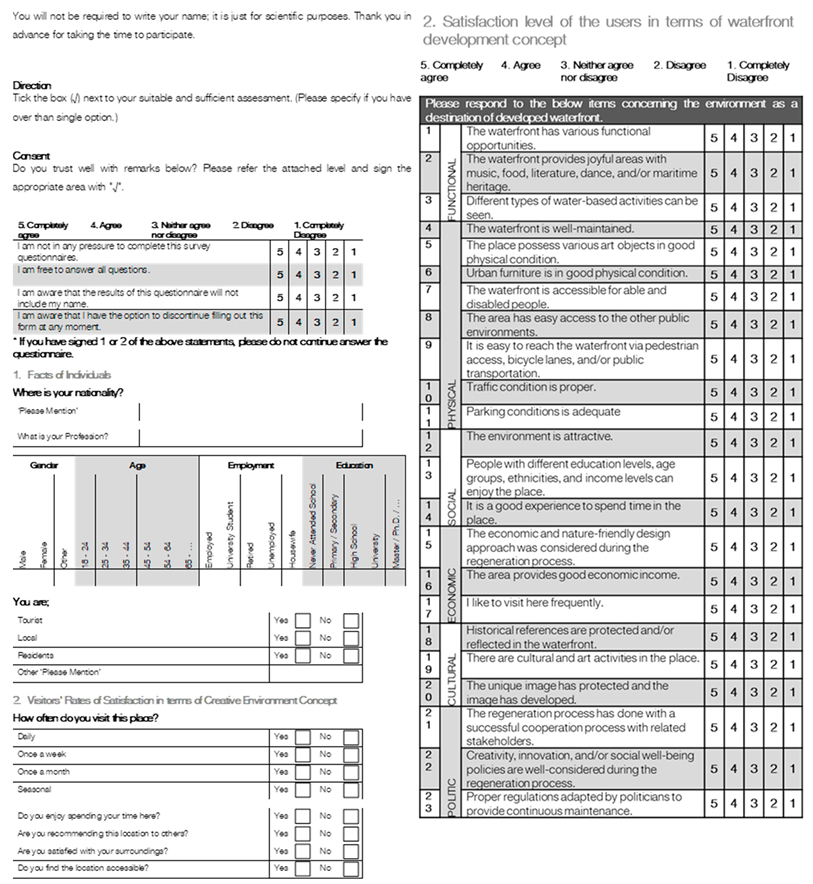

3.1. Measurement Instruments

3.2. The Sample and Data Collection

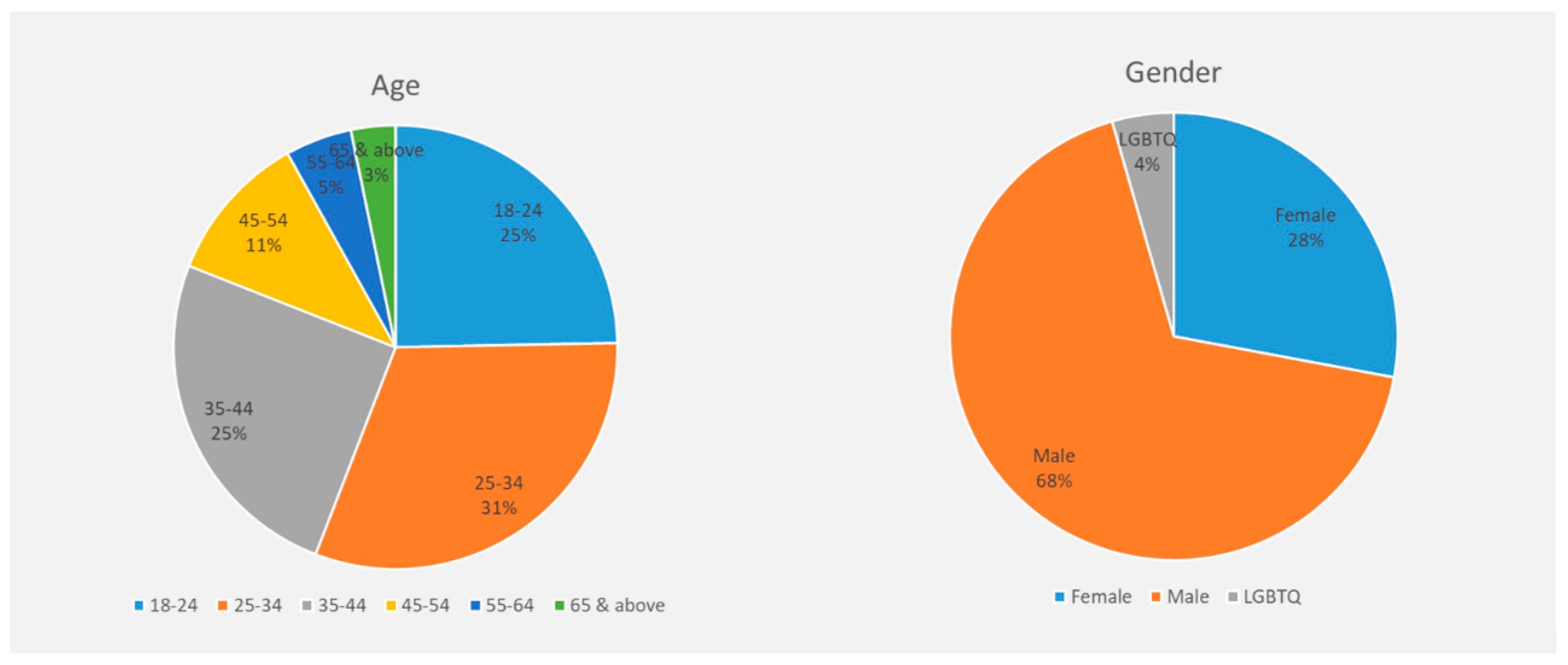

3.3. Participants

4. Results

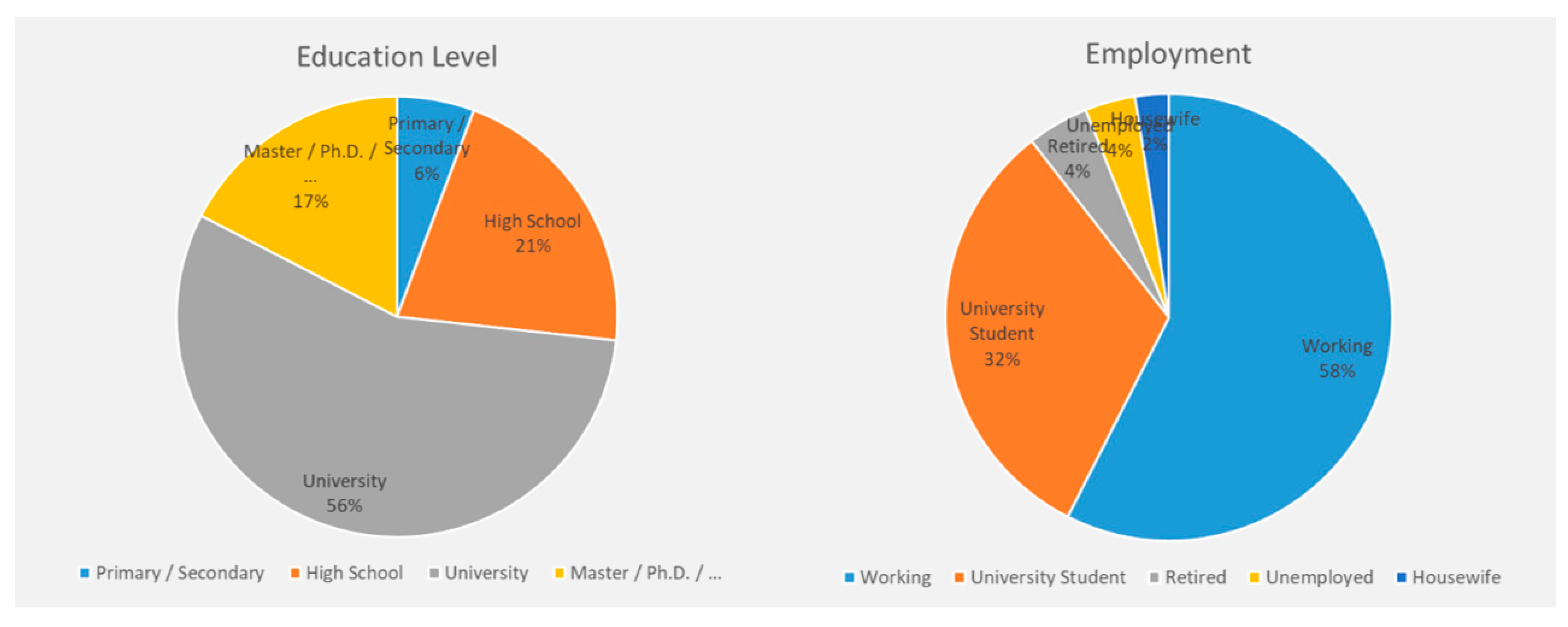

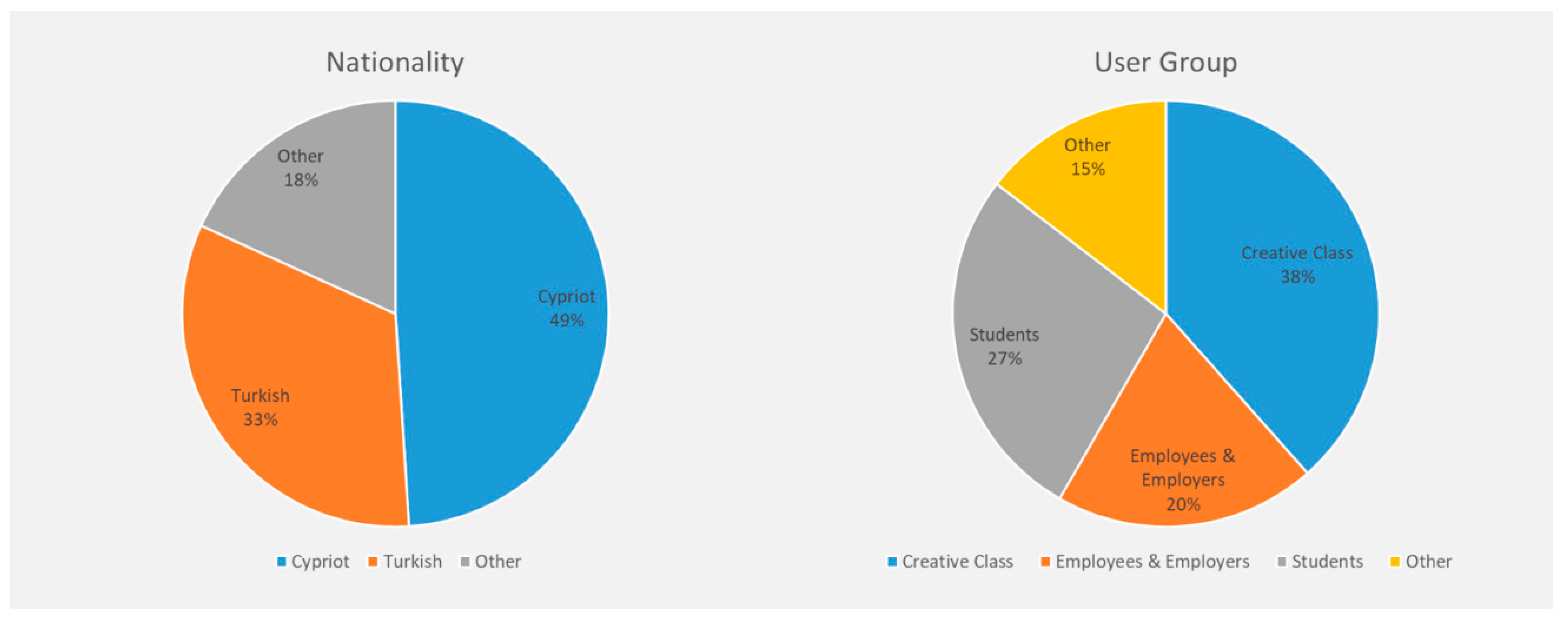

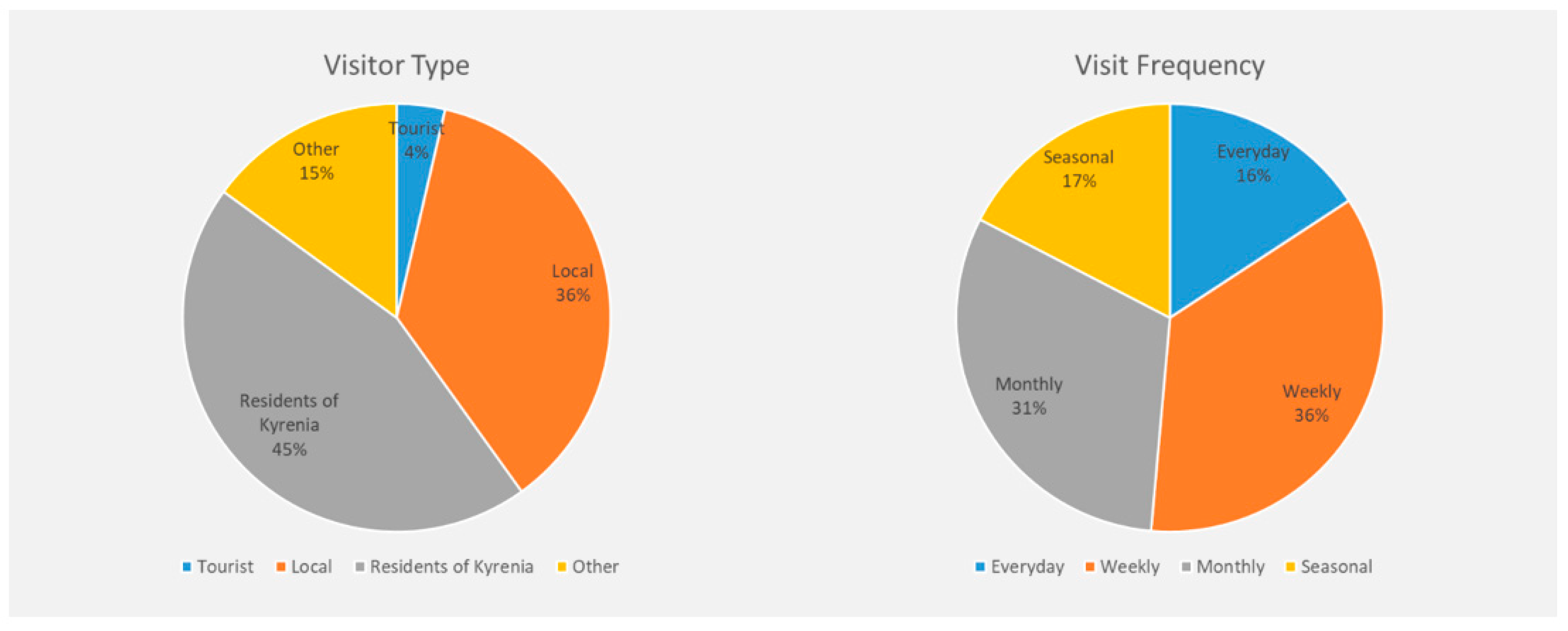

4.1. Respondents’ Profile

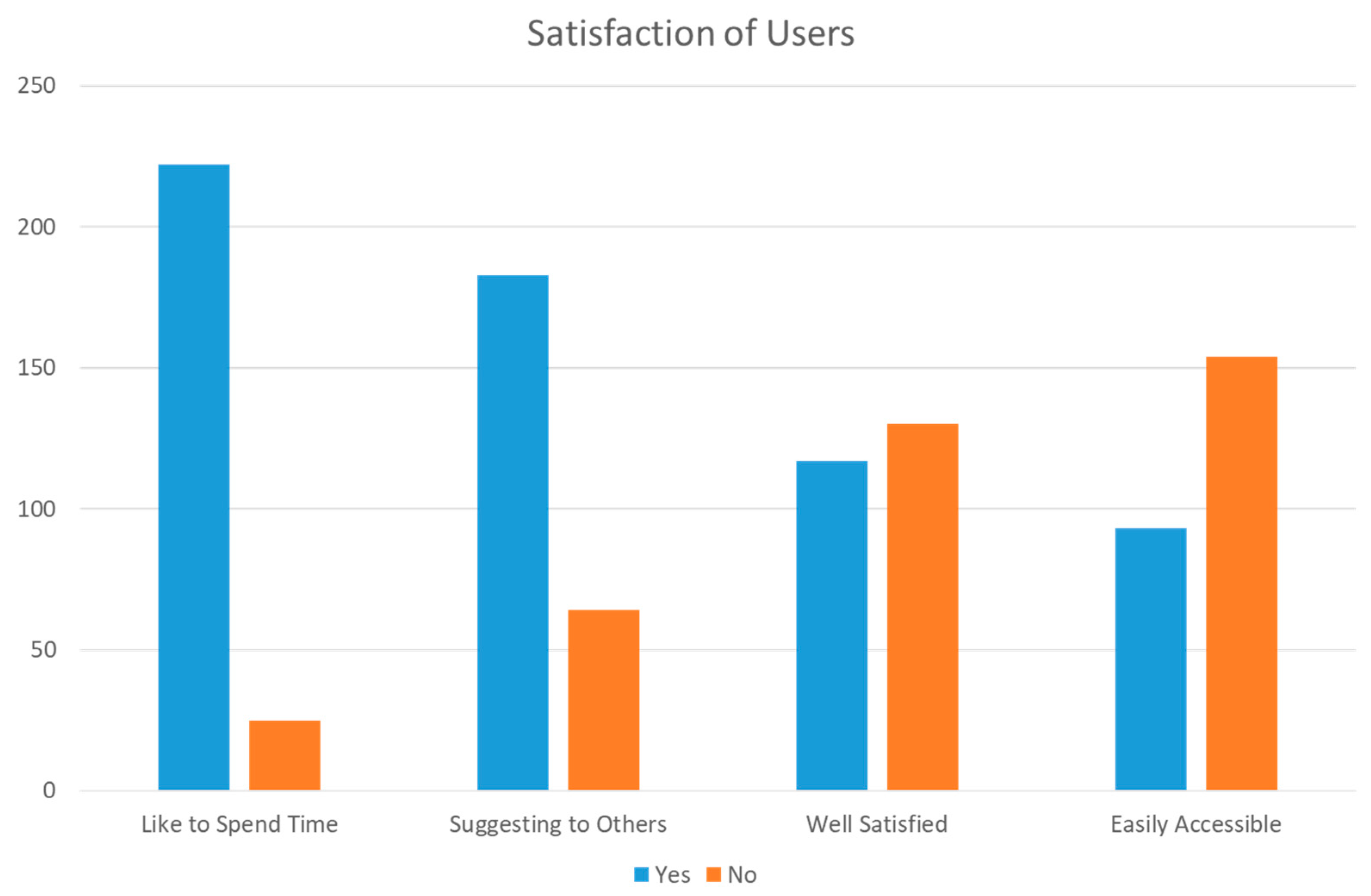

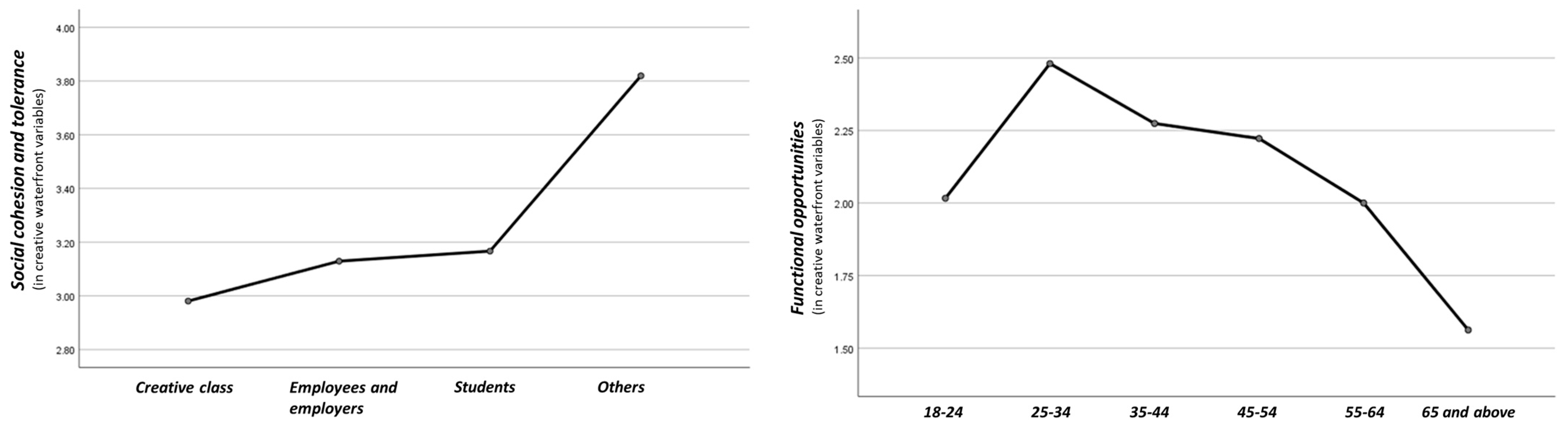

4.2. On Users’ Perceptions and Needs

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Beaches should be well-maintained, and more resting areas should be available for all users;

- Afforestation and environmental landscaping are needed;

- Recycle bins need to be installed;

- Bike paths need to be traced;

- Adequate sitting opportunities should be provided for the users;

- Infrastructure problems need to be solved; it is necessary to make a plan based on population estimates for the coming years;

- Public transport should be promoted to solve the traffic problem.

- Alternative tourism potential needs to be considered by producing new projects (such as creative tourism and cultural tourism);

- Providing free internet access and benefiting from technology, such as simulation areas;

- There should be a place for research and development, and classrooms should be encouraged to be creative and useful.

- Training and seminars should be organized to increase environmental awareness. Recycling awareness should be increased;

- Creative people and businesspeople should take part in decision-making.

- For development projects, an economical and nature-friendly design should be considered;

- Increasing economic income opportunities through alternative tourism options.

- More promotion is needed for historic buildings. Cultural and artistic activities should be increased;

- The unique image needs to be protected, and contemporary image standards should be satisfied.

- The government and municipality should provide financing for the development;

- Municipalities, governments, and the public should work in cooperation;

- The local authorities should identify the priority problems and bring these issues forward and develop projects accordingly;

- The public should act together by cooperating with the relevant institutions and organizations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Iwata, N.; del Rio, V. The Image of the Waterfront in Rio de Janeiro: Urbanism and Social Representation of Reality. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2004, 24, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoyle, B. Urban waterfront revitalization in developing countries: The example of Zanzibar’s Stone Town. Geogr. J. 2002, 168, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators; Earthscan Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, C.; Bianchini, F. The Creative City; The Round: Gloucestershire, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J.; Storper, M. The Nature of Cities: The Scope and Limits of Urban Theory. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kozina, J.; Bole, D.; Tiran, J. Forgotten values of industrial city still alive: What can the creative city learn from its industrial counterpart? City Cult. Soc. 2021, 25, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onen, M. Examination Rivers’ Recreational Potential as an Urban Coastal Space: Case Study, Eskisehir Porsuk Creek and Istanbul Kurbagalidere; Istanbul Technical University: Istanbul, Turkey, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Timur, U.P. Urban Waterfront Regenerations. 2013. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/45422 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Hattapoğlu, M.Z. Place of Water Phenomenan in Evoluation of Settlements and Teinterpretation of It as an Urban Design Element; Mimar Sinan Arts of University, Institute of Science and Technology: İstanbul, Turkey, 2004; p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Waterfront Manifesto. 1999. Available online: http://www.waterfrontcenter.org/about/manifesto.html (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Popovic, S.; Vlahovic, S.; Vatin, N. The Role of Water in City Center, through Location of “Rakitje”. Procedia Eng. 2015, 117, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoyle, B. The port—City interface: Trends, problems and examples. Geoforum 1989, 20, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, A.; Rigby, D. Waterfronts Cities Reclaim Their Edge; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Desfor, G.; Goldrick, M.; Merrens, R. Redevelopment on the North American water-frontier: The case of Toronto. In Revitalising the Waterfront; International Dimentions of Dockland Redevelopment; Hoyle, B.S., Pinder, D.A., Husain, M.S., Eds.; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1988; pp. 92–113. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.; Garcia Ferrari, M.S. Waterfront Regeneration: Experiences in City-Building; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Samavati, S.; Ranjbar, E. The Effect of Physical Stimuli on Citizens’ Happiness in Urban Environments: The Case of the Pedestrian Area of the Historical Part of Tehran. J. Urban Des. Ment. Health 2017, 2. Available online: https://www.urbandesignmentalhealth.com/journal2-tehran.html (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Carmona, M.; Heath, T.; Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alsumsam, I. Improving the Quality of Public Open Spaces in Hama, Syria: An Investigation through the Social Spatial Approach; The University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wessells, A.T. Urban Blue Space and ‘The Project of the Century’: Doing Justice on the Seattle Waterfront and for Local Residents. Buildings 2014, 4, 764–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, S.; Roy, A.K. Social Sustainability of Urban Waterfront—The Case of Carter Road Waterfront in Mumbai, India. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2017, 37, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.F.; Gu, K. The changing urban morphology: Waterfront redevelopment and event tourism in New Zealand. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 15, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space; Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P. Study on the Representation of Traditional Graphic Elements in Coastal Landscape Planning and Design. J101384 J. Coast. Res. 2020, 115, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moughtin, C. Urban Design-Street and Square; Butterworth Architecture: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, B.; Maturo, A. Knowing the urban landscape for a sustainable environmental. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 5257–5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, A.; Rigby, D. Urban waterfront: Positive directions urban problems. In Proceedings of the Recreational Conference, Mertyle Beach, SC, USA, 28 February–1 March 1985; pp. 60–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sealey, K.S.; Andiroglu, E.; Lamere, J.; Sobczak, J.; Suraneni, P. Multifunctional Performance of Coastal Structures Based on South Florida Coastal Environs. J. Coast. Res. 2021, 37, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Marine Litter: A Global Challenge; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, N.; Caton, B. Coastal Management in Australia; University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Cui, K. Coastal Landscape Architecture Design Based on Nonlinear Thinking. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 107, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloš, M.; Dragana, V. Mythology as a Driver of Creative Economy in Waterfront Regeneration: The Case of Savamala in Belgrade, Serbia. Space Cult. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L. Dis/embedded Geographies of Film: Virtual Panoramas and the Touristic Consumption of Liverpool Waterfront. Space Cult. 2010, 13, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, A.; Rigby, D. The New Waterfront: A Worldwide Urban Success Story; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Giovinazzi, O.; Moretti, M. Port Cities and Urban Waterfront: Transformations and Opportunities. TeMALab J. 2010, 3, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kostopoulou, S. On the Revitalized Waterfront: Creative Milieu for Creative Tourism. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4578–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Latip, N.S.A.; Shamsudin, S.; Liew, M.S. Functional Dimension at ‘Kuala Lumpur Waterfront’. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porteous, J.D. Design with people. Environ. Behav. 1977, 3, 206–223. [Google Scholar]

- Wuijts, S.; de Vries, M.; Zijlema, W.; Hin, J.; Elliott, L.R.; Breemen, L.D.; Scoccimarro, E.; Husman, A.M.; Külvik, M.; Frydas, I.S.; et al. The health potential of urban water: Future scenarios on local risks and opportunities. Cities 2022, 125, 103639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirou, C. Municipal advancement and tourism policy in the United States: Economic development and urban restructuring. In A Research Agenda for Urban Tourism; van der Borg, J., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 201–217. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. Issues in waterfront regeneration: More sobering thoughts. A UK perspective. Plan. Pract. Res. 1998, 13, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pirlone, F.; Spadaro, I.; De Nicola, M.; Sabattini, M. Sustainable urban regeneration in port-cities. A participatory project for the Genoa waterfront. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2022, 1, 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sairinen, R.; Kumpulainen, S. Assessing social impacts in urban waterfront regeneration. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2006, 26, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückner, A.; Falkenberg, T.; Heinzel, C.; Kistemann, T. The Regeneration of Urban Blue Spaces: A Public Health Intervention? Reviewing the Evidence. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 782101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q. Research on Architectural Space Design of Coastal Cities Based on Virtual Reality Technology. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 115, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seçmen, S. New Public Spaces of Post-Industrial Waterfronts. In Urban Waterfronts and Cultural Heritage; New Perspective and Opportunities; Babalis, D., Townshend, T.G., Eds.; Altralinea Edizioni: Florence, Italy, 2018; pp. 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gunay, Z.; Dokmeci, V. Culture-led regeneration of Istanbul waterfront: Golden Horn Cultural Valley Project. Cities 2012, 29, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, S.; Desfor, G. Introduction to “Political ecologies of urban waterfront transformations”. Cities 2007, 24, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boland, P.; Bronte, J.; Muir, J. On the waterfront: Neoliberal urbanism and the politics of public benefit. Cities 2017, 61, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hagerman, C. Shaping neighborhoods and nature: Urban political ecologies of urban waterfront transformations in Portland, Oregon. Cities 2007, 24, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodora, Y.; Spanogianni, E. Assessing coastal urban sprawl in the Athens’ southern waterfront for reaching sustainability and resilience objectives. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 222, 106090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.; Carlton, J.S.; Ma, Z. Drivers of revitalization in Great Lakes coastal communities. J. Great Lakes Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.; Paddison, R. Introduction: The Rise and Rise of Culture-led Urban Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The Rise of Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tiesdell, S.; Oc, T.; Heath, T. Revitalizing Historic Urban Quarters; Architectural Press, An imprint of Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, B. Scale and sustainability: The role of community groups in Canadian port-city waterfront change. J. Transp. Geogr. 1999, 7, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheochari, T.; Coccossis, H. Development of a waterfront regeneration tool to support local decision making in the context of integrated coastal zone management. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2019, 169, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, B. A rediscovered resource: Comparative Canadian perceptions of waterfront redevelopment. J. Transp. Geogr. 1994, 2, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyana Romero, V.; Maffei, L.; Brambilla, G.; Ciaburro, G. Modelling the soundscape quality of urban waterfronts by artificial neural networks. Appl. Acoust. 2016, 111, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, B. Global and Local Change on the Port-City Waterfront. Geogr. Rev. 2000, 90, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, M. Waterfronts between Sicily and Malta: An integrated and creative planning approach. PortusPlus 2012, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. Regenerating Urban Waterfronts—Creating Better Futures—From Commercial and Leisure Market Places to Cultural Quarters and Innovation Districts. Plan. Pract. Res. 2017, 32, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, M. Creative Urban Regeneration between Innovation, Identity and Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 12, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrenn, D.M.; Casazza, J.A.; Smart, J.E. Urban Waterfront Development; Urban Land Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, R. Waterfronts in Post-Industrial Cities; Spon Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meiner, A. Integrated maritime policy for the European Union—Consolidating coastal and marine information to support maritime spatial planning. J. Coast. Conserv. 2010, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenio, E.; Mossa, M. On the Need for an Integrated Large-Scale Methodology of Coastal Management: A Methodological Proposal. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angradi, T.R.; Launspach, J.J.; Wick, M.J. Human well-being and natural capital indicators for Great Lakes waterfront revitalization. J. Great Lakes Res. 2022, 48, 1104–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, M. The Thatcher Government’s Urban Policy, 1979–1989: A Review; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Vallega, A. Urban waterfront facing integrated coastal management. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2001, 44, 379–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desfor, G. Transforming Urban Waterfronts: Fixity and Flow; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, N. On the waterfront: The role of planners and consultants in waterside regeneration. Planner 1989, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Norcliffe, G.; Bassett, K.; Hoare, T. The emergence of postmodernism on the urban waterfront: Geographical perspectives on changing relationships. J. Transp. Geogr. 1996, 4, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C. City of Change and Challenge; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, H. City and Port: Transformation of Port Cities: London, Barcelona, New York and Rotterdam; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Avni, N.; Teschner, N. Urban Waterfronts: Contemporary Streams of Planning Conflicts. J. Plan. Lit. 2019, 34, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, C.V.; Witzling, L.P. Urban design as public policy: Integrating planning, design, programming and fundraising. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Making Cities Livable, Venice, Italy, 6 July 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ley, D. Liberal Ideology and the Postindustrial City. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1980, 70, 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownill, S. Developing London’s Docklands; Paul Chapman Publishing: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pryke, M.; Lee, R. Place your bets: Towards an understanding of globalisation, socio-financial engineering and competition within a financial centre. Urban Stud. 1995, 32, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B. History at the water’s edge. In Waterfronts in Post-Industrial Cities; Marshall, R., Ed.; Spon Press: London, UK, 2001; pp. 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Begg, I. Urban Competitiveness: Policies for Dynamic Cities; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Ashworth, G.J. City branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddulph, M. Urban design, regeneration and the entrepreneurial city. Prog. Plan. 2011, 76, 63–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, A. Urban Regeneration in the UK; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, J.H.; Krantzberg, G.; Alsip, P. Thirty-five years of restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern: Gradual progress, hopeful future. J. Great Lakes Res. 2020, 46, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravagnan, C.; Rossi, F.; Amiriaref, M. Sustainable Mobility and Resilient Urban Spaces in the United Kingdom. Practices and Proposals. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. The Informational City. Information TechnDlogy, Economic Restructuring, and the Urban-Regional Process; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P. The Self-Organizing Economy; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Begg, I. Cities and Competitiveness. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, J. The international proliferation of integrated coastal zone management efforts. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 1993, 21, 45–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, M.; Garcia Ferrari, S.; Thiam, S.; Smith, H. The Cool Sea: Waterfront Communities Project Toolkit; The Waterfront Communities Project; Edinburg Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Creel, L. Ripple Effects: Population and Coastal Regions; Population Reference Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Agardy, T.; Alder, J. Coastal Systems. In Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Current State and Trends; Dayton, P., Curran, S., Kitchingman, A., Wilson, M., Catenazzi, A., Restrepo, J., Birkeland, C., Blaber, S.J.M., Saifullah, S., Branch, G.M., et al., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 513–550. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, E.E.; Rosa, R.; Brito, J.L.S.; Ferreira, L.G. Land cover mapping of the tropical savanna region in Brazil. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 166, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.D.N. Climate change adaptation in coastal cities of developing countries: Characterizing types of vulnerability and adaptation options. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2020, 25, 739–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guvenbas, G.; Polay, M. Post-occupancy evaluation: A diagnostic tool to establish and sustain inclusive access in Kyrenia Town Centre. Indoor Built Environ. 2020, 30, 1620–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrenia Municipality Council. Kyrenia Region, Regional Strategic Development Plan 2019–2021; Kyrenia Municipality Council: Kyrenia, Cyprus, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fasli, M.; Pakdel, F. Assessing Laguna District’s Spatial Qualities in Gazimagusa, Northern Cyprus. Open House Int. 2010, 35, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sposito, V.A.; Hand, M.L.; Skarpness, B. On the efficiency of using the sample kurtosis in selecting optimal lpestimators. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 1983, 12, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, B.; Pottinger, G. Inclusive Access, Sustainability and the Built Environment; CEM Occasional Paper Series; The College of Estate Management: Reading, UK, 2010; Available online: www.ucem.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/inclusive-access.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

| Waterfront Development Principles | Decline Process from the 1970s | Renewal Process | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The 1980s | The 1990s | The 2000s | The 2010s | The 2020s | |

| Physical | 1. Flexibility of use [22] 2. Accessibility [22] 3. Rebuilding images, infrastructure, and the environment [64] | 1. Less attention to the environmental issues [41] 2. Importance of Environmental incorporation [41] | 1. Recreate the image of the city [2,65] 2. Urban competitiveness [65] | 1. City and water linkage [62,66] 2. Creation of physical structure, settlement, and permeability [61] 3. Opportunities for expansion [8] 4. A scale issue during development [62] | 1. City and water linkage [67] 2. equitable and sustainable improvements in human physical, mental, cultural, and socioeconomic well-being [68] |

| Functional | 1. Diversity of building type [22] 2. Office-led, and leisure-led development [69] 3. Necessary, optional and social activities [22] | 1. Diversity of building types [13,41] | 1. resorts, hotels, bungalows, restaurants, cafes, and retail establishments [29] 2. Combining private and public uses, like retail and entertainment [70] | 1. Diversification of traditional port-related uses [71] 2. Residential, leisure, tourism, commercial, and other public use opportunities [15,36] 3. Creative waterfront regeneration ‘Uses’ [61] | 1. Playgrounds, green spaces, lighting components, and safety issues [23] 2. Considering waterfronts as multifunctional spaces [32] 3. Protect, improve, or restore the natural environment (e.g., green space, biodiversity) [68] |

| Social | 1. Increasing employment opportunities [27] 2. The impact on interaction capabilities [72] 3. The impact on socio-economic characters [72] | 1. Socioeconomic common life [73] 2. The growing environmental and social concerns [41] 3. local community participation [41] | 1. Environmental and social concerns [74,75] 2. Bring people back to deserted areas [65] 3. Employment opportunities [74] | 1. Importance of safe and secure use [8] 2. Innovation and creativity in waterfront regeneration [62] 3. Community resilience issues [62] 4. “standardization” or “homogenization” issues [62] 5. Social equalities/inequalities [76] | 1. Safe and secure use persons with disabilities and those without [28] 2. Citizens’ education and training [51] 3. Healthy, socially equitable, and safe city [39,68] 4. A reliable indicator of income, homeownership, health, education, social cohesion, and divorce [68] |

| Economic | 1. Establishing a common ground for constructive action [77] 2. The deindustrialization of production, labor market, and occupations [78] 3. Economic revenue generation through tourism [64] | 1. Construction of business headquarters [13] 2. Market-led approach [79] 3. Lack of public funding [41] 4. Urban competitiveness [80] | 1. Public-private partnerships and extensive private investment [81] 2. Recapturing global investment [65] 3. Increasing local real income [82] 4. Place branding and marketing [83] | 1. Entrepreneurial governance [84] 2. Economic globalization and competitiveness [85] 3. Increasing marketing opportunity [15] 4. Creative Waterfront regeneration ‘Production’, ‘Projects’ [61] 5. Reuse opportunity [8] | 1. Proper economic and fiscal motivations and methods for local and regional growth [51] 2. The economic benefits ‘e.g., housing market impacts; increased tourism’ [86] 3. International and national collaboration and communication [51] |

| Cultural | 1. Contribution to cultural fabric [27] | 1. Preserving historical and architectural heritage [41] | 1. Balancing cultural and quality of life [81] 2. Buildings, structures, and artifacts that are part of cultural heritage [70] | 1. Temporary cultural event opportunities [8] 2. Cultural sensitivity, and capacity issues [62] 3. Maintain public safety, conserve cultural heritage, and memorialize local culture [76] | 1. Culture, health, and socioeconomic integration [68] 2. Networking socially and culturally [87] 3. Enhancing cultural heritage [87] |

| Politic | 1. Development of short- and long-term strategies [88] 2. Planning and assessing waterfronts by considering conflict, cooperation, and competition [14] | 1. Public-private partnership [13] 2. Policy analysis and formulation [41,79,89,90] 3. Sustainability and resilience [91] | 1. Network between waterfront communities [92] 2. Concerning the strategic planning framework [74] 3. Sustainability and resilience [93] | 1. Consumed carelessly, often without planning [94] 2. Legal instruments and institutional mechanisms, as required, to ensure the sustainability [95] 3. Visionary process management [62] 4. Promoting entrepreneurship [62] | 1. Socioeconomic sensitivity, sustainability, and resilience [96] 2. Adaptation to climate change, energy neutrality, and health crises [51] 3. Monitoring and providing funds [51] |

| Variables | Mean | Mode | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The waterfront has various functional opportunities. | 2.992 | 2 | 1.272 | 0.039 | −1.066 | 1 | 5 |

| The waterfront is providing joyful areas with music, food, literature, dance, and/or maritime heritage. | 2.563 | 2 | 1.201 | 0.625 | −0.434 | 1 | 5 |

| Different types of water-based activities can be seen. | 2.211 | 2 | 1.139 | 0.877 | 0.119 | 1 | 5 |

| Variables | Mean | Mode | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The waterfront is well maintained. | 2.178 | 2 | 1.048 | 0.877 | 0.454 | 1 | 5 |

| The place has presented various art objects in good physical condition. | 2.231 | 2 | 1.032 | 1.003 | 0.899 | 1 | 5 |

| Urban furniture is in good physical condition. | 2.162 | 2 | 1.070 | 0.938 | 0.405 | 1 | 5 |

| A certain level of mobility has been attained. The waterfront is accessible for people with a disability and those without. | 2.069 | 1 | 1.189 | 1.022 | 0.104 | 1 | 5 |

| The area has access to other public environments. | 2.243 | 1 | 1.235 | 0.819 | −0.336 | 1 | 5 |

| It is easy to reach the waterfront via pedestrian access, bicycle lanes, and/or public transportation. | 1.947 | 1 | 1.079 | 1.084 | 0.481 | 1 | 5 |

| Traffic and parking conditions are proper. | 2.150 | 1 | 1.178 | 0.909 | 0.049 | 1 | 5 |

| Adequacy of car parking opportunities is sufficient | 1.915 | 1 | 1.088 | 1.354 | 1.365 | 1 | 5 |

| Variables | Mean | Mode | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The environment is attractive. | 2.834 | 2 | 1.307 | 0.212 | −1.132 | 1 | 5 |

| People with different education levels, age groups, ethnicities, and income levels can enjoy the place. | 3.126 | 2 a | 1.410 | −0.023 | −1.331 | 1 | 5 |

| I am proud to have such a place in my city. | 3.138 | 3 | 1.327 | −0.150 | −1.099 | 1 | 5 |

| Variables | Mean | Mode | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The economic and nature-friendly design approach was considered during the regeneration process. | 2.417 | 1 | 1.230 | 0.577 | −0.540 | 1 | 5 |

| The area provides good economic income. | 2.846 | 2 | 1.275 | 0.161 | −1.067 | 1 | 5 |

| I like to visit here frequently. | 2.899 | 2 | 1.295 | 0.178 | −1.034 | 1 | 5 |

| Variables | Mean | Mode | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical references are protected and/or reflected in the waterfront. | 2.344 | 2 | 1.182 | 0.749 | −0.252 | 1 | 5 |

| There are cultural and art activities in the place. | 2.166 | 2 | 1.134 | 1.019 | 0.488 | 1 | 5 |

| The unique image has been protected and the image has developed. | 2.215 | 2 | 1.107 | 0.834 | 0.199 | 1 | 5 |

| Variables | Mean | Mode | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The regeneration process has been undertaken in successful cooperation with related stakeholders. | 2.211 | 2 | 1.076 | 0.656 | −0.159 | 1 | 5 |

| Creativity, innovation, and/or social well-being policies are considered during the regeneration process. | 2.186 | 2 | 1.066 | 0.678 | −0.143 | 1 | 5 |

| I am feeling that proper regulations have been created by politicians to provide continuous maintenance. | 2.040 | 1 | 1.055 | 0.820 | 0.052 | 1 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Üzümcüoğlu, D.; Polay, M. Urban Waterfront Development, through the Lens of the Kyrenia Waterfront Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159469

Üzümcüoğlu D, Polay M. Urban Waterfront Development, through the Lens of the Kyrenia Waterfront Case Study. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159469

Chicago/Turabian StyleÜzümcüoğlu, Doğa, and Mukaddes Polay. 2022. "Urban Waterfront Development, through the Lens of the Kyrenia Waterfront Case Study" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159469