Overcoming Growth Challenges of Sustainable Ventures in the Fashion Industry: A Multinational Exploration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ 1: Why do many sustainable ventures encounter growth challenges despite an increasingly favorable consumer sentiment, and what are the major barriers facing the small businesses?

- RQ 2: How can sustainable fashion managers deal with the amalgam of challenges at the intersection of fashion, sustainability and entrepreneurship?

2. Founding and Managing Sustainable Fashion Businesses

2.1. Sustainability in the Fashion Industry

2.2. Challenges for Sustainable Fashion Companies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Foundation

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Marketing to Distribution Partners and Consumers

4.2. Limited Resources

4.3. Supply Chain Management

5. Discussion

5.1. Improving Marketing

5.1.1. Brand Management and Communication

5.1.2. Design and Product Development

5.2. Leveraging Resources

5.2.1. Separation of Design and Management

5.2.2. Bricolage for Mobilizing Resources

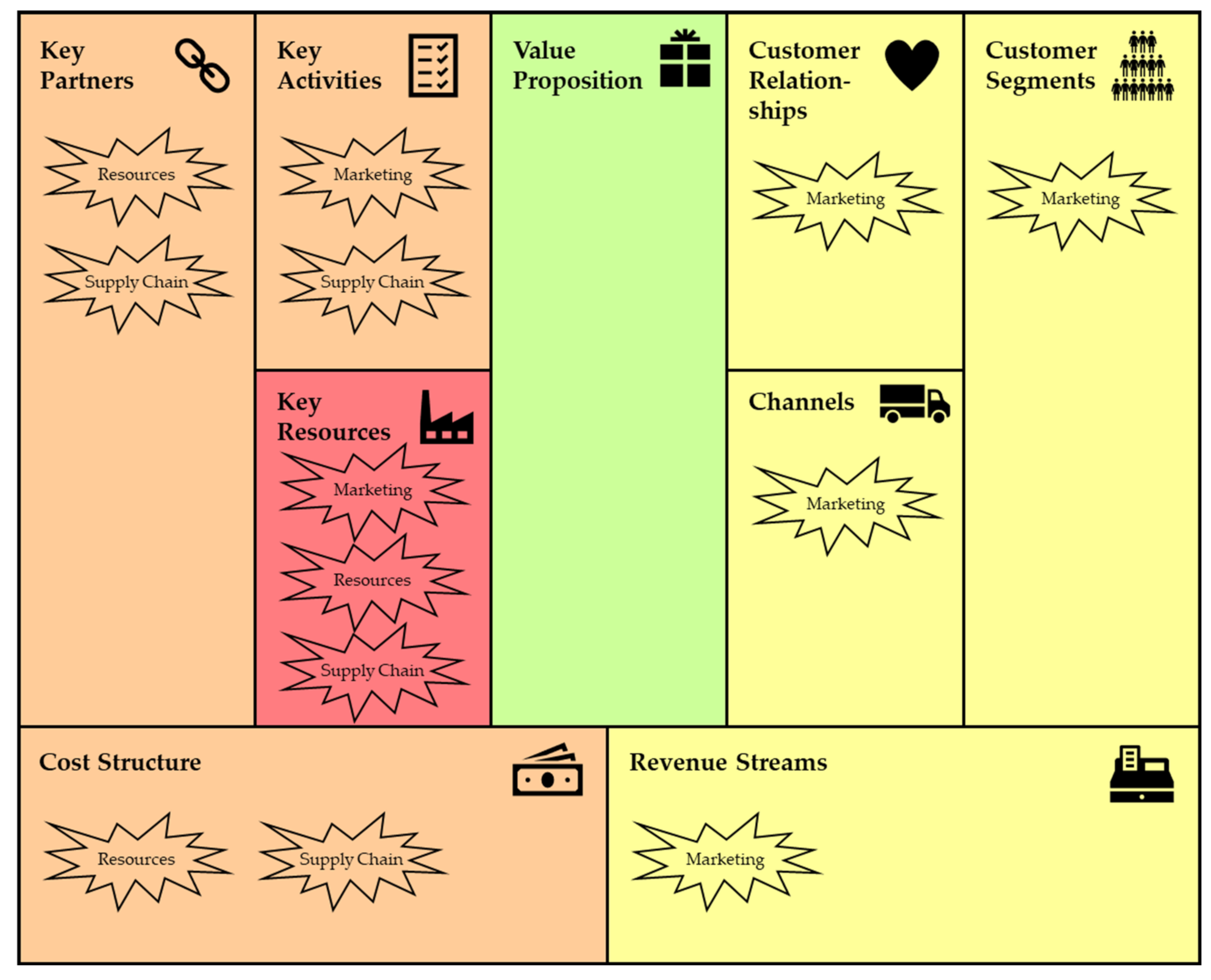

5.2.3. Business Model Analysis

5.2.4. Benefits of Existing Networks

5.3. Optimizing Supply Chains

- (i)

- Products incorporate expensive design elements (e.g., materials, production processes, etc.)

- (ii)

- Lack of experience curve effects

- (iii)

- Minimum order quantities prohibit sourcing materials from cheaper vendors

- (iv)

- Fixed costs apportion among small quantities, hence increasing average costs per unit produced

- (v)

- Employment of relatively inefficient production technology vis-à-vis incumbents with conventional business models

- (vi)

- Low bargaining power vis-à-vis suppliers

5.3.1. Collaborative Approaches with Other Fashion Ventures

5.3.2. Collaborative Approaches with Suppliers

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary

6.2. Implications for Practice and Theory

6.3. Limitations

6.4. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Guide for Semi-Structured Interviews

- What is the name of the company you are representing?

- Where is the company located (i.e., city and country)?

- What is your position?

- If additional company representatives attend the event, what are their positions?

- In which countries does your company produce its products?

- Please describe the sustainable/ethical characteristics of your business model.

- 7.

- How would you describe the relationship between ‘Ethical Fashion’ and ‘Sustainability’?

- 8.

- Which people/organizations come to your mind when you think about the main players in ‘Ethical Fashion’?

- 9.

- Which opportunities do you see for ‘Ethical Fashion’?

- 10.

- What are the main risks for ‘Ethical Fashion’ and your company, in particular?

- 11.

- Which challenges do you encounter related to operations and daily business?

- 12.

- Which challenges do you encounter related to medium- and long-term planning?

- 13.

- Which changes will be necessary for making more progress related to the ‘Ethical Fashion’ agenda?

- 14.

- Do you see any need for more collaboration to address the challenges?

- 15.

- Which topics are most relevant for collaborative activities?

- 16.

- What would be the preferred collaborative format (incl. participants and mode)?

- 17.

- Why are you visiting the Ethical Fashion Show Berlin?

- 18.

- What are your expectations from visiting this fair?

- 19.

- Have you visited any other fairs/events with a focus on sustainability?

- 20.

- How many representatives of your company are visiting this fair?

- 21.

- May we contact you for any further questions?

References

- Pucker, K.P. The Myth of Sustainable Fashion. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/01/the-myth-of-sustainable-fashion (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Berkey, B. Sweatshops, Structural Injustice, and the Wrong of Exploitation: Why Multinational Corporations Have Positive Duties to the Global Poor. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Henriques, I.; Husted, B.W. Beyond Good Intentions: Designing CSR Initiatives for Greater Social Impact. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 937–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Appolloni, A.; Cheng, W.; Huisingh, D. Aligning corporate social responsibility practices with the environmental performance management systems: A critical review of the relevant literature. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2022, 1–25, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amed, I.; Berg, A.; Balchandani, A.; Hedrich, S.; Rölkens, F.; Young, R.; Poojara, S. The State of Fashion 2020; McKinsey & Company: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rausch, T.M.; Kopplin, C.S. Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Hyder, Z.; Imran, M.; Shafiq, K. Greenwash and green purchase behavior: An environmentally sustainable perspective. Env. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13113–13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, G.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Do Transparent Business Practices Pay? Exploration of Transparency and Consumer Purchase Intention. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2011, 29, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, M.-L.; Tan, L.P. An exploration of environmentally-conscious consumers and the reasons why they do not buy green products. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 804–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, A.; Searcy, C.; Bardecki, M. The reDesign canvas: Fashion design as a tool for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luksha, P. Niche construction: The process of opportunity creation in the environment. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2008, 2, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, B.; van der Zwan, P.; Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 1133–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Davis, L.; Davis, D. Secrets in Fashion Entrepreneurship: Exploring Factors Influencing Success in U.S. Fashion New Ventures. In Proceedings of the International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2019; p. 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids—Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkovics, N.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Archie-Acheampong, J. Small- and medium-sized enterprises and sustainable development: In the shadows of large lead firms in global value chains. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2021, 4, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Simeone, A.; Sirén, C.; Antretter, T. New Venture Survival: A Review and Extension. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 378–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruderl, J.; Preisendorfer, P.; Ziegler, R. Survival Chances of Newly Founded Business Organizations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1992, 57, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielnik, M.M.; Zacher, H.; Schmitt, A. How Small Business Managers’ Age and Focus on Opportunities Affect Business Growth: A Mediated Moderation Growth Model. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017, 55, 460–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, R.; Josefy, M.; McMullen, J.S.; Shepherd, D. Organizational and Management Theorizing Using Experiment-Based Entrepreneurship Research: Covered Terrain and New Frontiers. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 759–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, W.L.; Bals, L. Achieving Shared Triple Bottom Line (TBL) Value Creation: Toward a Social Resource-Based View (SRBV) of the Firm. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 803–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-87641-1. [Google Scholar]

- Priem, R.L.; Butler, J.E. Is the Resource-Based “View” a Useful Perspective for Strategic Management Research? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Sherry, J.F.; Venkatesh, A.; Wang, J.; Chan, R. Fast Fashion, Sustainability, and the Ethical Appeal of Luxury Brands. Fash. Theory 2015, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freise, M.; Seuring, S. Social and environmental risk management in supply chains: A survey in the clothing industry. Logist. Res. 2015, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R.G.; Gwozdz, W.; Hvass, K.K. Exploring the Relationship Between Business Model Innovation, Corporate Sustainability, and Organisational Values within the Fashion Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M.; Micheletti, M. Introducing the Sustainability Challenge of Textiles and Clothing. J. Consum. Policy 2016, 39, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R.G.; Andersen, K.R. Sustainability innovators and anchor draggers: A global expert study on sustainable fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2015, 19, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergens, C. Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2006, 10, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito, M.P.; Carbone, V.; Blanquart, C.M. Towards a sustainable fashion retail supply chain in Europe: Organisation and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 114, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Slow Fashion: An Invitation for Systems Change. Fash. Pract. 2010, 2, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Oates, C.J. What is sustainable fashion? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, D.; Strähle, J.; Müller, M.; Freise, M. Social Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Textile and Apparel Industry—A Literature Review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukendi, A.; Davies, I.; Glozer, S.; McDonagh, P. Sustainable fashion: Current and future research directions. EJM 2020, 54, 2873–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. From “Green Blur” to Ecofashion: Fashioning an Eco-lexicon. Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, T.-M.; Chan, T.; Wong, C.W. The consumption side of sustainable fashion supply chain. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretto, A.; Macchion, L.; Lion, A.; Caniato, F.; Danese, P.; Vinelli, A. Designing a roadmap towards a sustainable supply chain: A focus on the fashion industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Wood, A.M.; Gargeya, V.B. Sustainable entrepreneurship in the apparel industry: Passion and challenges. J. Text. Inst. 2021, 113, 1935–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, B.V.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; Callegaro-de-Menezes, D.; Ghezzi, A. Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieth, H.; Bullinger, A.C.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the Apparel Industry. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2012, 2012, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefko, R.; Steffek, V. Key Issues in Slow Fashion: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolacci, F.; Caputo, A.; Soverchia, M. Sustainability and financial performance of small and medium sized enterprises: A bibliometric and systematic literature review. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.; Castañeda-Ayarza, J.A.; Lombardo Ferreira, D.H. Sustainable Strategic Management (GES): Sustainability in small business. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, M.; Martinez, L.F. Ethical consumer behaviour in Germany: The attitude-behaviour gap in the green apparel industry. Int. J. Consum Stud. 2018, 42, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, S.F.C.; Lee, C.K.C. Leveraging the power of online social networks: A contingency approach. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 345–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridakis, G.; Lai, Y.; Mohammed, A.-M.; Hansen, J.M. Industry characteristics, stages of E-commerce communications, and entrepreneurs and SMEs revenue growth. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 128, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić Rosario, A.; Sotgiu, F.; De Valck, K.; Bijmolt, T.H. The Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth on Sales: A Meta-Analytic Review of Platform, Product, and Metric Factors. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduku, D.K.; Mpinganjira, M.; Duh, H. Understanding mobile marketing adoption intention by South African SMEs: A multi-perspective framework. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kumar Kar, A. Why do small and medium enterprises use social media marketing and what is the impact: Empirical insights from India. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J.H.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.P.; Silvestre, B.S. Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, C.; Shearer, L. Taking sustainable fashion mainstream: Social media and the institutional celebrity entrepreneur. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, B.V.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; de Medeiros, J.F. Collaboration practices in the fashion industry: Environmentally sustainable innovations in the value chain. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 106, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiVito, L.; Bohnsack, R. Entrepreneurial orientation and its effect on sustainability decision tradeoffs: The case of sustainable fashion firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Haugh, H.; Chambers, L. Barriers to Social Enterprise Growth. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 1616–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Brettel, M.; Mauer, R. The Three Dimensions of Sustainability: A Delicate Balancing Act for Entrepreneurs Made More Complex by Stakeholder Expectations. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.-J.; Choi, T.-M. A United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals perspective for sustainable textile and apparel supply chain management. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 141, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelze, N. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Implementation-Enablers and Barriers in the Textile Industry. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Beckmann, M.; Hockerts, K. Collaborative entrepreneurship for sustainability. Creating solutions in light of the UN sustainable development goals. IJEV 2018, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B.; Harrison, R. Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurs’ Decisions to Exploit Opportunities. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.; Bamel, U. Extending the resource and knowledge based view: A critical analysis into its theoretical evolution and future research directions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, L.S.; Barney, J.B. What can Strategy Learn from the Business Model Approach? J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. (Notified under document number C(2003) 1422), (Text with EEA relevance), (2003/361/EG). Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, 124, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P.; Fenzl, T. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-658-21307-7. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781506330204. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S. Data analysis in qualitative research. Evid.-Based Nurs. 2000, 3, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnock, O. Sustainable Fashion Wants Brands to Redefine Business Growth. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/oliviapinnock/2021/09/24/degrowth-is-trending-in-sustainable-fashion-what-does-that-mean-for-brands/?sh=431c59304a6f (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Business Wire. Global Ethical Fashion Market Report 2020: Opportunities, Strategies, COVID-19 Impacts, Growth and Change, 2019–2030. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210111005582/en/Global-Ethical-Fashion-Market-Report-2020-Opportunities-Strategies-COVID-19-Impacts-Growth-and-Change-2019-2030—ResearchAndMarkets.com (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- D’Souza, C. Marketing Challenges for an Eco-fashion Brand: A Case Study. Fash. Theory 2015, 19, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.; Moore, R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legere, A.; Kang, J. The role of self-concept in shaping sustainable consumption: A model of slow fashion. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, N.; Saricam, C. The Impact of Knowledge on Consumer Behaviour Towards Sustainable Apparel Consumption. In Consumer Behaviour and Sustainable Fashion Consumption; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; pp. 69–96. ISBN 978-981-13-1264-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay, C.; Ray, S. Finding the Sweet Spot between Ethics and Aesthetics: A Social Entrepreneurial Perspective to Sustainable Fashion Brand (Juxta)Positioning. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, T.H. Strategic CSR Communication: A Moderating Role of Transparency in Trust Building. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2018, 12, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; de los Salmones Sanchez, M.D.M.G.; del Bosque, I.R. Understanding Corporate Social Responsibility and Product Perceptions in Consumer Markets: A Cross-cultural Evaluation. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 80, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C. Enterprise orientations: A framework for making sense of fashion sector start-up. Int. J. Ent. Behav. Res. 2011, 17, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. From quantity to quality: Understanding slow fashion consumers for sustainability and consumer education. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindova, V.P.; Williamson, I.O.; Petkova, A.P.; Sever, J.M. Being Good or Being Known: An Empirical Examination of the Dimensions, Antecedents, and Consequences of Organizational Reputation. AMJ 2005, 48, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reficco, E.; Gutiérrez, R.; Jaén, M.H.; Auletta, N. Collaboration mechanisms for sustainable innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 1170–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granskog, A.; Lee, L.; Magnus, K.-H.; Sawers, C. Survey: Consumer Sentiment on Sustainability in Fashion; McKinsey & Company: Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goworek, H.; Oxborrow, L.; Claxton, S.; McLaren, A.; Cooper, T.; Hill, H. Managing sustainability in the fashion business: Challenges in product development for clothing longevity in the UK. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.; Oxborrow, L.; Claxton, S.; Hill, H.; Goworek, H.; McLaren, A.; West, K. Clothing Durability Dozen: Report by Nottingham Trent University for Defra (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs); Nottingham Trent University: Nottingham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T.; Demirguc-Kunt, A. Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. J. Bank. Financ. 2006, 30, 2931–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grichnik, D.; Brinckmann, J.; Singh, L.; Manigart, S. Beyond environmental scarcity: Human and social capital as driving forces of bootstrapping activities. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desa, G.; Basu, S. Optimization or Bricolage? Overcoming Resource Constraints in Global Social Entrepreneurship. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2013, 7, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Nelson, R.E. Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, M.; Haugh, H.; Tracey, P. Social Bricolage: Theorizing Social Value Creation in Social Enterprises. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Entrepreneurship in and around institutional voids: A case study from Bangladesh. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.G. Falling Forward: Real Options Reasoning and Entrepreneurial Failure. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopfer, M.; Fallahi, S.; Kirchberger, M.; Gassmann, O. Adapt and strive: How ventures under resource constraints create value through business model adaptations. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2017, 26, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Hughes, K.D.; Zhao, W. Resource combination activities and new venture growth: Exploring the role of effectuation, causation, and entrepreneurs’ gender. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 59, S73–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostgaard, T.A.; Birley, S. New venture growth and personal networks. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R. A Review of Recent Trends in Sustainable Fashion and Textile Production. CTFTTE 2019, 4, 555648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, F.Y.; Moon, K.L.; Ng, S.F.; Hui, C.L. Production sourcing strategies and buyer-supplier relationships. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2007, 11, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faes, W.; Matthyssens, P.; Vandenbempt, K. The Pursuit of Global Purchasing Synergy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotanus, F.; Telgen, J.; de Boer, L. Critical success factors for managing purchasing groups. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2010, 16, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydges, T.; Lavanga, M.; Von Gunten, L. Entrepreneurship in the Fashion Industry: A Case Study of Slow Fashion Businesses. In Beyond Frames: Dynamics between the Creative Industries, Knowledge Institutions and the Urban Context; Schramme, A., Kooyman, R., Hagoort, G., Eds.; Eburon Academic Publishers: Delft, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 73–79. ISBN 978-90-5972-884-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgreen, A.; Ellegaard, C. The purchasing orientation of small company owners. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2009, 24, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressey, A.D.; Winklhofer, H.M.; Tzokas, N.X. Purchasing practices in small- to medium-sized enterprises: An examination of strategic purchasing adoption, supplier evaluation and supplier capabilities. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2009, 15, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thopte, I.; Poldner, K. David and Goliath in sustainable fashion: Strategic business alliances in the UK fashion industry. IJSBA 2014, 3, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekhar, D. Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) In India: Opportunities and Challenges; Working Papers 66; Institute for Social and Economic Change: Bangalore, India, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Environmental management and manufacturing performance: The role of collaboration in the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theyel, G.; Hofmann, K. Stakeholder relations and sustainability practices of US small and medium-sized manufacturers. Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 1110–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.; Auster, E. Even dwarfs started small: Liabilities of age and size and their strategic implications. Res. Organ. Behav. 1986, 8, 165–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, G.A.; Lyons, T.S. Revisiting the Business Life-Cycle. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2008, 9, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.T.; Pandian, J.R. The resource-based view within the conversation of strategic management. Strat. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, T.; Hinings, C.R. Managing the Rivalry of Competing Institutional Logics. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.C.; McNally, J.J.; Kay, M.J. Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedajlovic, E.; Honig, B.; Moore, C.B.; Payne, G.T.; Wright, M. Social Capital and Entrepreneurship: A Schema and Research Agenda. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Term | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical Fashion | “[…] ethical fashion can be defined as fashionable clothes that incorporate fair trade principles with sweatshop-free labour conditions while not harming the environment or workers by using biodegradable and organic cotton”. | [30] |

| Slow Fashion | “Slow fashion represents a vision of sustainability in the fashion sector based on different values and goals to the present day. It requires a changed infrastructure and a reduced throughput of goods. Categorically, slow fashion is not business-as-usual but just involving design classics. Nor is it production-as-usual but with long lead times. Slow fashion represents a blatant discontinuity with the practices of today’s sector; a break from the values and goals of fast (growth-based) fashion”. | [32] |

| Eco-Fashion | “Eco-fashion is defined as the type of clothing that is designed and manufactured to maximize benefits to people and society while minimizing adverse environmental impacts”. | [38] |

| Sustainable Fashion | “Sustainability in fashion and textiles fosters ecological integrity, social quality and human flourishing through products, action, relationships and practices of use”. | [37] |

| “[…] includes the variety of means by which a fashion item or behaviour could be perceived to be more sustainable, including (but not limited to) environmental, social, slow fashion, reuse, recycling, cruelty-free and anti-consumption and production practices”. | [35] |

| Interview ID | Position Interviewee | Location Headquarter | Main Location Manufacturing | Year Established | Firm Category | Product Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Managing Director | Belgium | China | 2016 | Micro | Apparel |

| 2 | Chief Marketing Officer | Germany | Portugal | 1982 | Small | Footwear |

| 3 | Founder | Slovenia | Slovenia | 2015 | Micro | Apparel |

| 4 | Managing Director | Germany | Germany | 1982 | Small | Apparel/Home Textiles |

| 5 | Chief Executive Officer | Spain | India | 2010 | Micro | Apparel |

| 6 | Founder/Designer | Germany | Germany | 2012 | Micro | Apparel |

| 7 | Designer | England | China/Nepal/Cameroon/Japan | 1988 | Medium | Apparel/Footwear |

| 8 | Owner/Designer | Malaysia | Malaysia | 2012 | Small | Apparel |

| 9 | Founder | Netherlands | Multiple Asian countries | 2013 | Small | Apparel/Footwear |

| 10 | Founder/Designer | Slovenia | Slovenia | 2015 | Micro | Apparel |

| 11 | Head of Sales | Denmark | Poland | 1975 | Medium | Footwear |

| 12 | Owner/Designer | Latvia | Latvia | 2016 | Micro | Apparel |

| 13 | Chief Marketing Officer | Spain | Spain | 2016 | Micro | Apparel |

| 14 | Chief Executive Officer | Sweden | Latvia | 2013 | Micro | Swimwear |

| 15 | Country Manager | Netherlands | Nepal | 2008 | Small | Apparel/Homewear/Body Care |

| 16 | Owner | Switzerland | Lithuania | 2014 | Micro | Apparel |

| 17 | Managing Director | Austria | Austria/Hungary | 2009 | Small | Apparel |

| 18 | Founder | France | France | 2016 | Micro | Accessories |

| Category | Definition | Frequency | Subcategory | Definition | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marketing | Risks and challenges re. marketing and sales activities | 30 | R&D/Design | Risks and challenges re. market research, product development and design | 6 |

| Pricing | Risks and challenges re. pricing | 6 | |||

| Consumer | Risks and challenges re. end consumer communication, promotion and services | 18 | |||

| General administration/organization | Risks and challenges re. internal and organizational aspects | 25 | Resources | Risks and challenges re. organizational framework, staff, employees’ skills, knowledge, finances, etc. | 18 |

| Growth | Risks and challenges re. growth and general development of the company | 7 | |||

| Supply chain management | Risks and challenges re. sourcing and distribution processes | 20 | Sourcing | Risks and challenges re. sourcing process of materials and supplier relations | 8 |

| Manufacturing | Risks and challenges re. manufacturing process, incl. techniques, costs, staff, etc. | 10 | |||

| Distribution | Risks and challenges occurring after the manufacturing process, incl. distribution to retailers and consumers | 2 | |||

| Market environment | Risks and challenges re. market environment and external stakeholders | 13 | Stakeholders | Risks and challenges re. governments, regulations, media, NGOs, etc. | 6 |

| Competition | Risks and challenges re. competitors | 3 | |||

| Greenwashing | Statements re. concerns of greenwashing of incumbents | 4 | |||

| Certificates | Statements re. certificates, quality signals, etc. | 3 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Absence of challenges/risks | Statements indicating that challenges do not exist | 4 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hofmann, K.H.; Jacob, A.; Pizzingrilli, M. Overcoming Growth Challenges of Sustainable Ventures in the Fashion Industry: A Multinational Exploration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610275

Hofmann KH, Jacob A, Pizzingrilli M. Overcoming Growth Challenges of Sustainable Ventures in the Fashion Industry: A Multinational Exploration. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610275

Chicago/Turabian StyleHofmann, Kay H., Axel Jacob, and Massimo Pizzingrilli. 2022. "Overcoming Growth Challenges of Sustainable Ventures in the Fashion Industry: A Multinational Exploration" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610275

APA StyleHofmann, K. H., Jacob, A., & Pizzingrilli, M. (2022). Overcoming Growth Challenges of Sustainable Ventures in the Fashion Industry: A Multinational Exploration. Sustainability, 14(16), 10275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610275