Dysfunctional Family Mechanisms, Internalized Parental Values, and Work Addiction: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Work Addiction

1.2. Work Addiction and Social Relationships

1.3. Qualitative Research in the Field of Work Addiction and Our Research Question

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measurement Tools

2.3. Procedure

Method of Data Collection and Provision of Ethical Requirements

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

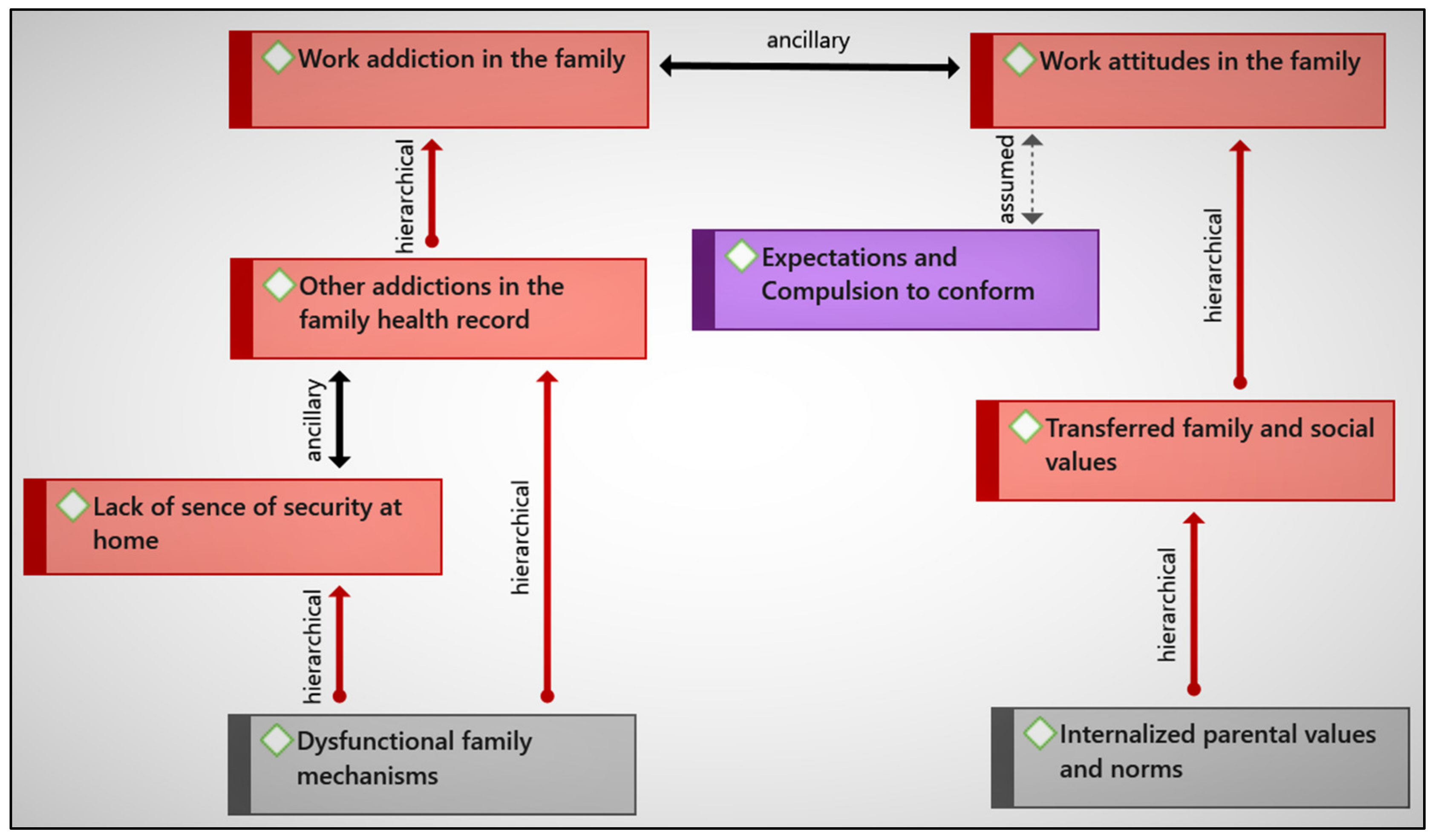

3.1. Dysfunctional Family Mechanisms

3.1.1. Lack of Sense of Security at Home

“And then later it also always drove me in my work to make as much money as possible, but in order to be able to make my dreams come true with money as a tool (…) in my childhood, we never vacationed anywhere with my family, because we didn’t have the financial opportunity, and then I wanted to somehow reach a level, so that I could be so independent and financially independent that after that I could realize my big childhood dreams (…) because I am not financially dependent on whether I can cover my daily subsistence.”(9.)

“So, I have a very difficult relationship with my parents, it’s hard in a way that there were very serious emotional bottlenecks (…) And accepting that, they couldn’t meet my kind of emotional needs like that, back then, and well, yes, over seventy it will obviously remain the same.”(8.)

“I was a good student because my mother worked a lot in a dairy. She couldn’t care for us, she never dealt with us, she put us in after school childcare.”(13.)

“Well, I find it very difficult to talk about my own emotions. I am a crier anyway, so I cry.”(25.)

“And my parents divorced, I have two siblings, she raised us alone, and er... actually, I think she has had 3 jobs in parallel since I was little.”(26.)

“My mother was a teacher and my parents divorced, so we didn’t live together, we didn’t keep in touch because he was English in the family and stayed in England.”(4.)

3.1.2. Work Addiction in the Family

“… My sister works in the marketing field and she has to start the whatever campaign and I don’t know what…She has to launch it at 2 a.m. for whatever reasons and…I can see it on her that she enjoys.”(6.)

“My mother, in her entire life, has always had a full-time job and a second and sometimes a third…”(28.)

“And you need to know about my parents that they work in education, but that they have 2–3 jobs and are 55 and 56 years old and they’re pushing that right now, as hard as they even work on the weekends.”(27.)

“My older daughter, who is about 36 years old, may already be working more than I am (sighing). She works twelve hours, she is er… a department manager at a big company… uhh… yeah, I think she works as much as I do. She works as much as I do, so for her it is completely natural to accept and understand this (…) It’s hard because of her job... she can’t live a full family life. She got married and after 8 months her husband said, “(We married to) … see you working day and night?”(13.)

3.1.3. Other Addictions in Family

“Well, I come from a relatively heavier family. My father was an alcoholic. There was a time when Mom was too, actually, it’s a complicated family with a wide variety of addictions. Even within the larger family, not just the close family.”

(Questioner: “What kind of addictions?”)

“All. In fact, all that you can imagine (laughs)”

(Questioner: “Could you mention some of them?”)

“There were drug users, many alcoholics, er…all kinds of relationship addicts. Horse race, betting, gambling was there too.”(25.)

“… I just got used to it, for example, that my father was an alcoholic. And well, it happened a lot of times that he came home, then he raged and broke things, and then we escaped with my sister…”(13.)

“… And so, I didn’t really see the signs, the situation wasn’t familiar, I didn’t see many drunk people where I grew up, and so even this euphoric state wasn’t recognizable to me.”(11.)

3.2. Internalized Parental Norms and Values

3.2.1. Transferred Family and Social Values

“Yes, they stand up from everything (…), but that what they have taught me about working and about taking responsibility for myself, well, it gives me a lot of strength and motivation.”(11.)

“But it’s something brought from home like this, so for me, my parents were like that too, so for me it’s totally essential that I pay attention to people.”(15.)

“Yes, I grew up in love, maybe this is..., yes, in love, between values and boundaries.”(11.)

(…) “So, I sometimes asked them for advice, yes, yes. But I usually don’t get in turn that I shouldn’t have done something in a way I did.” (…)

(Questioner: “So there is a good relationship between them?”)

(…) “So, uh yes, yes. Well, they’re older now.”(22.)

3.2.2. Work Attitudes in the Family

“Well, uh, so I think for us in the family, the first thing in life was work, the, the rest was also important, but still the most important thing was work. So, well, er… that’s why we live. If someone loves his job, well, it is like he likes to live. Yeah, so… So, without a sense of passion, it’s really hard to do this well. Mediocre yes, but not well.”(22.)

“So, I think I’m bringing this kind of attitude with me on a transgenerational level. Let’s just say I found a meaning in it now that I’m trying to… uh so I tried and managed to embrace that meaning of enjoying it. It’s my attitude right now, and at this point I don’t feel like I want to change it because now it’s mine. (…) I mean, when I was a kid and I experienced it and I became aware of it that I have this as well and I have this urge.”(20.)

“But I know it came through previous generations, so how can I say that we weren’t really that way that we opened ourselves very easily even on Saturday afternoons, or we didn’t go to Visegrád to eat a trout, but there is work to do. There is always much work to do around the house, ergo people do it.”(20.)

“Well, it’s actually a kind of parental legacy. So, when I was a child, my parents talked about things at work even at dinner and on the weekends, and in the evenings, they worked and planned.”(22.)

“There is, there is such a family background that the, it may sound strange, but… this is the service of the state, the service of the home country, if you can say such words, that’s how it is, my grandpa was a military officer and my godfather too, was a professional soldier, he also retired from there, the family has such a very militaristic line.”(12.)

(Questioner: “In your career choice, did you always know what you wanted to be?”)

“It was strong enough because my parents were chemical engineers (…) my parents had this profession, so there was a kind of motivation like that.”(22.)

3.2.3. Expectations and Compulsion to Conform

“So, I have such a fear, such an adequacy of being knocked down, even though I work a lot, and I have this feeling, that they will call me, and I don’t know, they will say I didn’t do it (my work) well or I overlooked something and that it should have been done in a different way.”(1.)

“Well, one enjoys, one enjoys that people work a lot, but somehow there is some compulsion to prove. To dad, mom, ourselves, I had that too, and I almost got my doctorate to make my parents satisfied with me (…) but I don’t fight anyone, anyone, just to make mom and dad happy. (…) Ah, I don’t want to prove to anyone anymore. I want to live. Because in the meantime I forgot to live. That’s what I found out.“(11.)

“So, my work addiction, if we call it that, let’s call it that, wasn’t, it was partly caused by such an external influence and such an undefined expectation, it is a compulsion in my opinion and that was what my personality met…”(21.)

“I think it’s an inner urge that makes me a workaholic, that I’m well with my life right now if what I’m doing is useful. Be the benefit small or big, whatever, but other than 0, there should be a positive benefit of what I’m doing. And I can achieve that by means of working.”(20.)

“But I didn’t think that I was doing it because… because otherwise the world would collapse, or then my life would be empty, because I would have been happy to occupy myself with something else, but I have a maximalism that might seem stupid from the outside, and absolute loyalty, and I don’t know what… and I knew that if I didn’t do that, then… everything would turn out so shitty, and that’s why I did it, but… but I’m sure I have a tendency towards this, but one has to watch this with awareness.”(18.)

“Well, I did realize that » Oh, wait, it isn’t normal that my dad treats me like that. Could he even admit that I am good at something?” (…) So that I never felt like my dad was proud of me. Whatever I did.”(23.)

“On the other hand, well, my dad, he, he’s proud of me, too, but with him, well, our relationship is a little different. It’s damn hard to meet his standards in anything, there’s the typical thing, that, er… if you do something well you don’t really get praise, but if you do something wrong, you get criticized badly.”(28.)

(Questioner: “Were you like this in school as well? Did you learn a lot?”)

“No. It’s so interesting, but I wasn’t. So, I was never an explicitly good student. (sighs) Since I was always very overwhelmed there too. I don’t know. It’s really very interesting that there wasn’t this. Not only the best grade was acceptable.”(23.)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, M.S.; Michel, J.S.; Zhdanova, L.; Pui, S.Y.; Baltes, B. All work and no play? A meta-analytic examination of the correlates and outcomes of workaholism. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1836–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atroszko, P.A.; Demetrovics, Z.; Griffiths, M.D. Beyond the myths about work addiction: Toward a consensus on definition and trajectories for future studies on problematic overworking: A response to the commentaries on: Ten myths about work addiction (Griffiths et al., 2018). J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Burke, R. Workaholism and relationship quality: A spillover-crossover perspective. J. Occup. Health Psych. 2009, 14, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonebright, C.A.; Clay, D.L.; Ankenmann, R.D. The relationship of workaholism with work–life conflict, life satisfaction, and purpose in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 2000, 47, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirrane, M.; Breen, M.; O’Connor, C. A qualitative study on the consequences of intensive working. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2017, 28, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, L.D. Reconstructing the “work ethic” through medicalized discourse on workaholism. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2013, 41, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassel, D. Working Ourselves to Death, 1st ed.; HarperCollins: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Machlowitz, M. Workaholics: Living with Them, Working with Them, 1st ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Hetland, J.; Pallesen, S. Workaholism and work–family spillover in a cross-occupational sample. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qiu, D.; Lau, M.C.M.; Lau, J.T.F. The mediation role of work-life balance stress and chronic fatigue in the relationship between workaholism and depression among Chinese male workers in Hong Kong. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Hetland, J.; Kravina, L.; Jensen, F.; Pallesen, S. The prevalence of workaholism: A survey study in a nationally representative sample of Norwegian employees. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Nielsen, M.B.; Pallesen, S.; Gjerstad, J. The relationship between psychosocial work variables and workaholism: Findings from a nationally representative survey. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2019, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, B.; Magi, A.; Felvinczi, K.; Demetrovics, Z.; Paksi, B. A munkafüggőség szociodemográfiai és pszichés háttere, elterjedtsége a hazai felnőtt lakosság körében: Egy országos reprezentatív felmérés eredményei. Psychiatr. Hung. 2020, 35, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berk, B.; Ebner, C.; Rohrbach-Schmidt, D. Wer hat nie richtig Feierabend?: Eine Analyse zur Verbreitung von suchthaftem Arbeiten in Deutschland. Arbeit 2022, 31, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalewicz, J.; Badora, B.; Feliksiak, M.; Głowacki, A.; Gwiazda, M.; Herrmann, M.; Kawalec, I.; Roguska, B. Oszacowanie Rozpowszechnienia Oraz Identyfikacja Czynników Ryzyka i Czynników Chroniących Hazardu i Innych Uzależnień Behawioralnych–Edycja 2018/2019; Polish Ministry of Health: Warszawa, Poland, 2019.

- Kang, S. Workaholism in Korea: Prevalence and socio-demographic differences. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 569744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Hetland, J.; Pallesen, S. Development of a work addiction scale. Scand. J. Psychol. 2012, 53, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Grant, J.E.; Potenza, M.N.; Weinstein, A.; Gorelick, D.A. Introduction to behavioral addictions. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010, 36, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atroszko, P.A.; Demetrovics, Z.; Griffiths, M.D. Work addiction, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, burn-out, and global burden of disease: Implications from the ICD-11. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oates, W.E. Confessions of a Workaholic: The Facts about Work Addiction, 1st ed.; World Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, G. Organizational impact of workaholism: Suggestions for researching the negative outcomes of excessive work. J. Educ. Psychol. 1996, 1, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E. Chained to the Desk: A Guidebook for Workaholics, Their Partners and Children and the Clinicians Who Treat Them, 1st ed.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; van Rhenen, W. Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottl, K.S.; Moore, K.S.; Miceli, M.P. An exploration of the meaning and consequences of workaholism. Hum. Relat. 1997, 50, 287–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Spagnoli, P.; Avanzi, L.; Clark, M. A daily diary investigation on the job-related affective experiences fueled by work addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, J.T.; Robbins, A.S. Workaholics: Definition, measurement, and preliminary results. J. Pers. Assess. 1992, 58, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naughton, T.J. A conceptual view of workaholism and implications for career counseling and research. Career Dev. Q. 1987, 35, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, B.; Hamrák, A.; Kenyhercz, V.; Demetrovics, Z.; Kaló, Z. Az egészségromlás és az egészségmagatartás-változás kvalitatív vizsgálata munkafüggők körében. Magy. Pszichológiai Szle. 2021, 76, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, L.H.; Brady, E.C.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Marsh, N.V. A multifaceted validation study of Spence and Robbins’ (1992) Workaholism Battery. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 2002, 75, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Sorensen, K.L.; Feldman, D.C. Dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of workaholism: A conceptual integration and extension. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluen, S.D.; Barling, J.; Burns, W. Predicting sales performance, job satisfaction, and depression by using the achievement strivings and impatience-irritability dimensions of type A behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, J.M. Obsessive-compulsive personality: A review. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, B.; Takacs, Z.K.; Richman, M.J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z. Work addiction and personality: A meta-analytic study. J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 9, 945–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S. Workaholism: An addiction to work. In Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse, 1st ed.; Preedy, V.R., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2016; Volume 3, pp. 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S.; Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: Developmental period facilitative of the addictions. Eval. Health Prof. 2014, 37, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B.F. About Behaviorism, 1st ed.; Random House USA Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.A.; Waters, L.E. Workaholic worker type differences in work–family conflict: The moderating role of supervisor support and flexible work scheduling. Career Dev. Int. 2006, 11, 418–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G. Workaholic tendencies and the high potential for stress among co-workers. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2001, 8, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Post, P. Risk of addiction to work and family functioning. Psychol. Rep. 1997, 81, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E. Work Addiction: Hidden Legacies of Adult Children; Health Communications Inc.: Deerfield Beach, FL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pietropinto, A. The workaholic spouse. Med. Asp. Hum. Sex. 1986, 20, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.L. Correlates of physical and emotional health among male and female workaholics. Diss. Abstr. Int. 1992, 53, 5446. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, R.J. Workaholism and divorce. Psychol. Rep. 2000, 86, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, L.H.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Brady, E.C. The impact of workaholism on personal relationships. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2004, 32, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Post, P. Work addiction as a function of family of origin and its influence on current family functioning. Fam. J. 1995, 3, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E. Workaholism and family functioning: A profile of familial relationships, psychological outcomes, and research considerations. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2001, 23, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Flowers, C.; Carroll, J. Work stress and marriage: A theoretical model examining the relationship between workaholism and marital cohesion. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2001, 8, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J. Workaholism among women managers: Work and life satisfactions and psychological well-being. Equal Oppor. Int. 1999, 18, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killinger, B. The workaholic breakdown syndrome. In Research Companion to Working Time and Work Addiction; Burke, R., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J.J.; Robinson, B.E. Depression and parentification among adults as related to parental workaholism and alcoholism. Fam. J. 2000, 8, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravina, L.; Falco, A.; De Carlo, N.A.; Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S. Workaholism and work engagement in the family: The relationship between parents and children as a risk factor. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, A.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Fujiwara, T.; Iwata, N.; Shimada, K.; Takahashi, M.; Tokita, M.; Watai, I.; Kawakami, N. Workaholism, work engagement and child well-being: A test of the spillover-crossover model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, G.; Kakabadse, N.K. HRM perspectives on addiction to technology and work. J. Manag. Dev. 2006, 25, 535–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, B.; Urbán, R.; Bőthe, B.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z.; Kökönyei, G. Maladaptive rumination mediates the relationship between self-esteem, perfectionism, and work addiction: A largescale survey study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 7332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Post, P.; Khakee, J.F. Test-retest reliability of the work addiction risk test. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1992, 74, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, R.; Kun, B.; Mozes, T.; Soltesz, P.; Paksi, B.; Farkas, J.; Kokonyei, G.; Orosz, G.; Maraz, A.; Felvinczi, K.; et al. A four-factor model of work addiction: The development of the Work Addiction Risk Test Revised (WART-R). Eur. Addict. Res. 2019, 25, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehota, J. Marketingkutatás az Agrárgazdaságban, 1st ed.; Mezőgazda Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners, 1st ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ATLAS.ti. Scientific Software Development GmbH. Qualitative Data Analysis, Version 9.0; ATLAS.ti.: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cree, V.E. Worries and problems of young carers: Issues for mental health. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2003, 8, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J.; Cederbaum, J.A.; Hurlburt, M.S. Parentification, substance use, and sex among adolescent daughters from ethnic minority families: The moderating role of monitoring. Fam. Process 2013, 53, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, N.D. Burdened Children: Theory, Research, and Treatment of Parentification; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin, C.M.; Zhang, N. Workaholism, health, and self-acceptance. J. Couns. Dev. 2009, 87, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand-Moreau, Q.; Le Deun, C.; Lodde, B.; Dewitte, J. The framework of clinical occupational medicine to provide new insight for workaholism. Ind. Health 2018, 56, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmet, S.; Studer, J.; Wicki, M.; Bertholet, N.; Khazaal, Y.; Gmel, G. Unique versus shared associations between self-reported behavioral addictions and substance use disorders and mental health problems: A commonality analysis in a large sample of young Swiss men. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujna, E. A szülői példa szerepe a nevelésben. Módszertani Közlemények 2009, 49, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, G.; Peterson, J.S.; Lawson, A. Alcoholism and the Family: A Guide to Treatment and Prevention, 1st ed.; Aspen Systems Corp.: Rockville, MD, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos, E.; Castro, C. Beyond the Big Five: The role of extrinsic life aspirations in compulsive buying. Psicothema 2017, 29, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; Lelchook, A.M.; Taylor, M.L. Beyond the Big Five: How narcissism, perfectionism, and dispositional affect relate to workaholism. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Guglielmi, D. Are workaholics born or made? Relations of workaholism with person characteristics and overwork climate. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2014, 21, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Themes | Sub-Themes | Frequency of Mentioning in All the Interviews (N) | Frequency of Mentioning among All Individuals N (%) | Percentage of Males Who Mentioned (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysfunctional family mechanisms | Lack of sense of security at home | 10 | 6 (21) | 100 |

| Work addiction in the family | 14 | 6 (21) | 67 | |

| Other addictions in the family | 7 | 7 (24) | 29 | |

| Internalized parental values and norms | Transferred family and social values | 6 | 6 (21) | 50 |

| Work attitudes in the family | 14 | 12 (41) | 42 | |

| Expectations and compulsion to conform | 29 | 17 (59) | 59 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kenyhercz, V.; Frikker, G.; Kaló, Z.; Demetrovics, Z.; Kun, B. Dysfunctional Family Mechanisms, Internalized Parental Values, and Work Addiction: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169940

Kenyhercz V, Frikker G, Kaló Z, Demetrovics Z, Kun B. Dysfunctional Family Mechanisms, Internalized Parental Values, and Work Addiction: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):9940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169940

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenyhercz, Viktória, Gabriella Frikker, Zsuzsa Kaló, Zsolt Demetrovics, and Bernadette Kun. 2022. "Dysfunctional Family Mechanisms, Internalized Parental Values, and Work Addiction: A Qualitative Study" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 9940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169940

APA StyleKenyhercz, V., Frikker, G., Kaló, Z., Demetrovics, Z., & Kun, B. (2022). Dysfunctional Family Mechanisms, Internalized Parental Values, and Work Addiction: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability, 14(16), 9940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169940