Individual Low-Cost Travel as a Route to Tourism Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

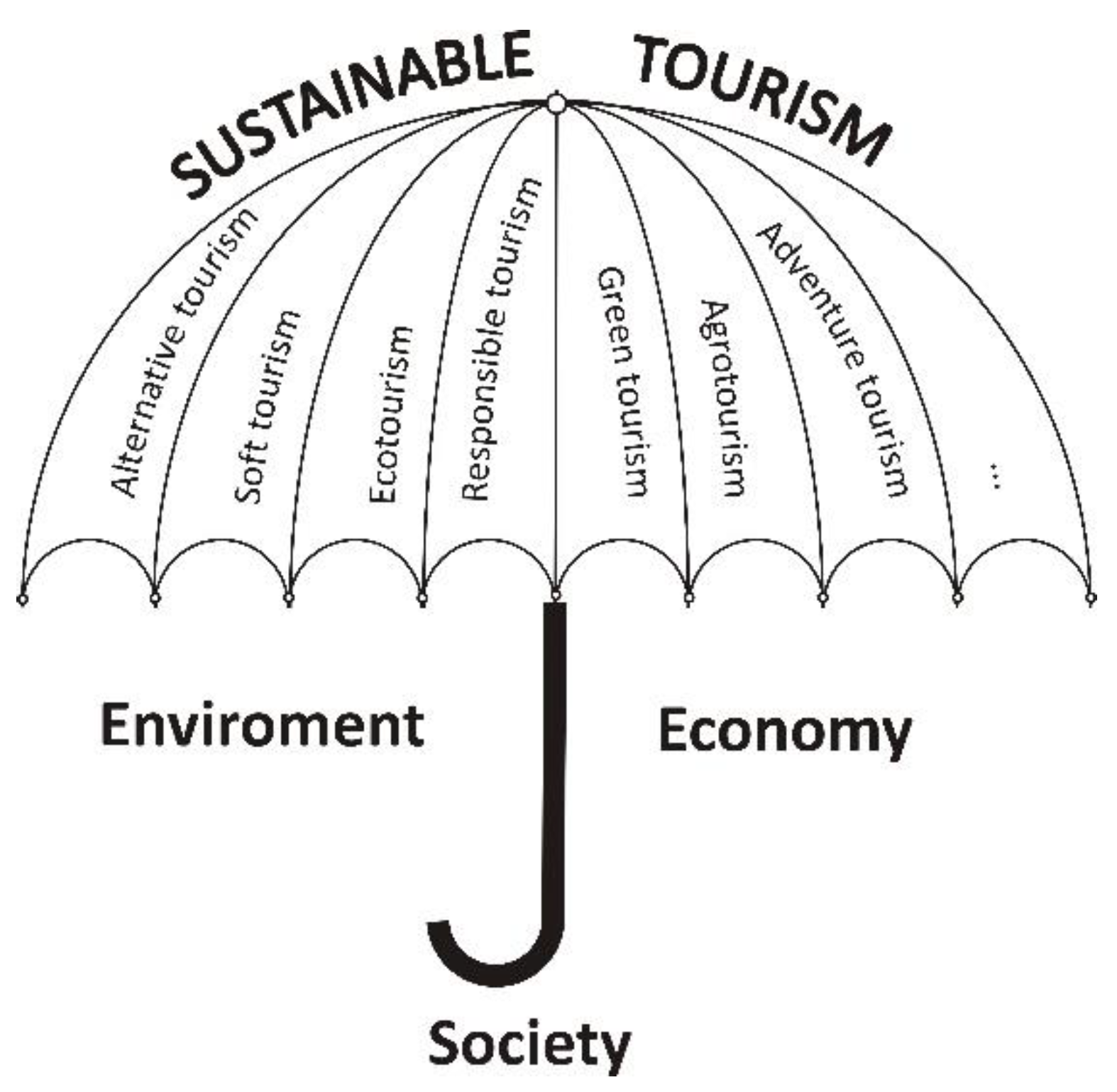

3. Sustainable Development and Tourism

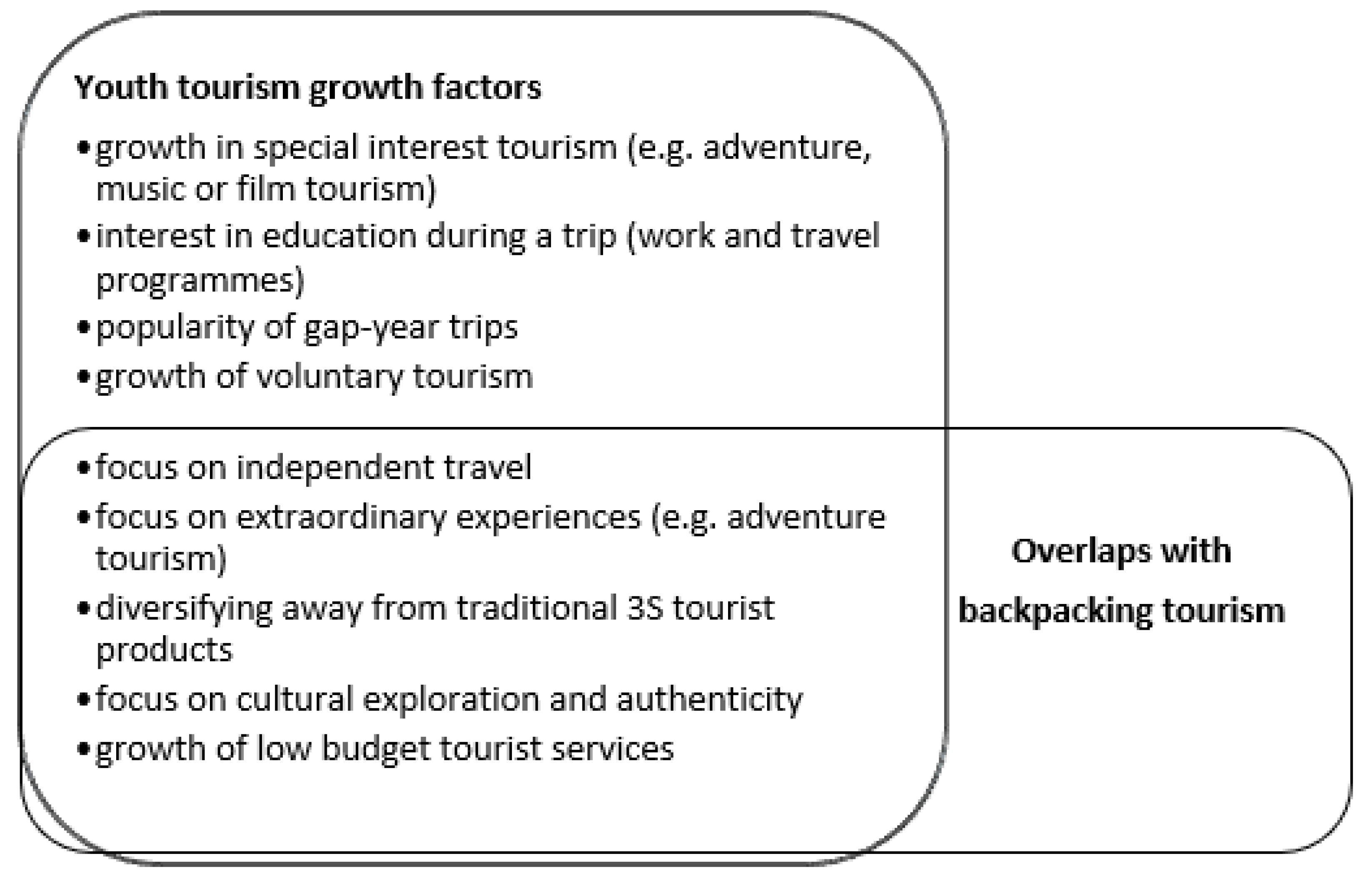

4. Low-Cost Travel and Its Potential for Sustainable Tourism Creation

- religious (prayer, spiritual experiences related to religion);

- cognitive–religious or religious–cognitive (depending on the proportion of activity) (prayer, spiritual experiences, sightseeing, learning about the history of holy places), which together can be included in so-called pilgrimage/ religious tourism;

- nonreligious (cognitive, not related to prayer or religious experiences), which can be included in cultural tourism (Figure 6).

5. Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williams, S.W. Tourism Geography; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liszewski, S. Przestrzeń turystyczna. Turyzm/Tourism 1995, 5, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, W. (Ed.) Turystyka; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gaworecki, W.W. Turystyka; PWE: Warsaw, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, A. Geografia Turyzmu; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowski, L.; Brzykca, A.; Rudnicki, R. Niskobudżetowa turystyka indywidualna jako forma aktywności turystycznej. Ekon. Probl. Tur. 2016, 33, 259–272. [Google Scholar]

- Zawadka, J.; Pietrzak-Zawadka, J. Individual Budget Travels as a Form of Leisure Among the Polish Citizens. In Innovative Approaches to Tourism and Leisure, Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference IACuDiT, Athens, Greece, 25–27 May 2017; Katsoni, V., Velander, K., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, T. Environmental responsibility and business regulation: The case of sustainable tourism. Geogr. J. 1997, 163, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Tourism destination development: Cycles and forces, myths and realities. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2009, 34, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, B.H. Conventional or sustainable tourism? No room for choice. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 189–191. [Google Scholar]

- Zaręba, D. Ekoturystyka; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Mirosa, M.; Bremer, P. Review of online food delivery platforms and their impacts on sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Merchant, A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rose, G. Writing an impactful review article: What do we know and what do we need to know? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, J.; Stasiak, A.; Włodarczyk, B. Produkt Turystyczny—Pomysł, Organizacja, Zarządzanie—Wydanie II Zmienione; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boz, Z.; Korhonen, V.; Koelsch Sand, C. Consumer considerations for the implementation of sustainable packaging: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, S.; Dangelico, R.M.; Nonino, F.; Pompei, A. Sustainable project management: A conceptualization-oriented review and a framework proposal for future studies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampridi, M.G.; Sørensen, C.G.; Bochtis, D. Agricultural sustainability: A review of concepts and methods. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehhi, A.; Nobanee, H.; Khare, N. The impact of sustainability practices on corporate financial performance: Literature trends and future research potential. Sustainability 2018, 10, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable Tourism as an Adaptative Paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 24, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niezgoda, A. Obszar Recepcji Turystycznej w Warunkach Rozwoju Zrównoważonego; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Niezgoda, A. The role of different tourism concepts and forms inthe pursuance of sustainable development goals. Turyzm 2008, 18, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED. Our Common Future. The Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Moldan, B.; Janoušková, S.; Hák, T. How to understand and measure environmental sustainability: Indicators and targets. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 17, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A. (Ed.) Turystyka Zrównoważona; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mika, M. Założenia i Determinanty Podtrzymywalności Lokalnego Rozwoju Turystyki; Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, K.E. The Meaning of the 20th Century: The Great Transition; Lanham University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W. The Limits to Growth; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, M. How to be an Ecological Economist; Working Papers 0454; University of Heidelberg, Depatment of Economics: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.R. World on the Edge; Earth Policy Institute: Norton, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tourism in the 2030 Agenda. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-in-2030-agenda (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Lane, B. What is rural tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Development of Tourism. Conceptual Definitions; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blamey, R.K. Principles of ecotourism. In The Encyclopedia of Ecotourism; Weaver, D.B., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2001; pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Niezgoda, A.; Zmyślony, P. Identyfing Determinants of the Development of Rural Tourist Destinations in Poland; Tourism; Institute for Tourism, Croatian National Tourist Board: Zagreb, Croatia, 2002; Volume 51, pp. 451–452. [Google Scholar]

- Eugenio-Martin, J.L.; Inchausti-Sintes, F. Low-cost travel and tourism expenditures. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loker-Murphy, L.; Pearce, P.L. Young budget travelers: Backpackers in Australia. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 819–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C.M.; Rogerson, J.M. Camping tourism: A review of recent international scholarship. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2020, 28, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Toward a sociology of international tourism. Soc. Res. 1972, 39, 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- Van Egmond, A.N.F. Understanding Western Tourists in Developing Countries; Cabi: Wallingford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ateljevic, I.; Doorne, S. Theoretical encounters: A review of backpacker literature. In The Global Nomad: Backpacker Travel in Theory and Practice; Richards, G., Wilson, J., Eds.; Chanell View Publications: Clevedon Hall, UK, 2004; pp. 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.; Richards, G. Suspending reality: An exploration of enclaves and the backpacker experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speed, C. Are backpackers ethical tourists? In Backpacker Tourism: Concepts and Profiles; Hannam, K., Ateljevic, I., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2008; pp. 54–81. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, C.M.; Teye, V. Backpacker motivations: A travel career approach. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzhofer, G. The roaring nineties Low-budget Backpacking in South-East Asia as an Appropriate Alternative to Third World Mass Tourism? Asien Afr. Lat. 2002, 30, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, A. Backpacker ethnography. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 847–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majstorović, V.; Stankov, U.; Stojanov, S. The presence of backpacking tourism in Europe. Turizam 2013, 17, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-H.; Huang, S.S. Backpacker tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, M. From its drifter past to nomadic futures: Future directions in backpacking research and practice. Tour. Stud. 2021, 21, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G.; Wilson, J. Youth tourism: Finally coming of age? In Niche Tourism; Novelli, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; King, B. Youth travel and backpacking. Travel Tour. Anal. 2003, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Demeter, T.; Bratucu, G. Typologies of youth tourism. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov. Econ. Sci. Ser. V 2014, 7, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Maoz, D. Backpackers Motivations: The role of culture and nationality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 34, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaquinto, B.L. “I recycle, I turn out the lights”: Understanding the everyday sustainability practices of backpackers. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 577–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaquinto, B.L.; Pratt, S. Practicing sustainability as a backpacker: The role of nationality. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; Dayour, F.; Otoo, F.E.; Goh, B. Understanding backpacker sustainable behavior using the tri-component attitude model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1193–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayour, F.; Adongo, C.A.; Taale, F. Determinants of backpackers’ expenditure. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, B. An existentialist exploration of tourism sustainability: Backpackers fleeing and finding themselves. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, N.; Laing, J.H. Backpacker tourism: Sustainable and purposeful? Investigating the overlap between backpacker tourism and volunteer tourism motivations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnaert, L.; Maitland, R.; Miller, G. What is social tourism? In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 872–873. [Google Scholar]

- Włodarczyk, B. Turystyka społeczna—Próba definicji zjawiska. In Turystyka Społeczna w Regionie Łódzkim; Stasiak, A., Ed.; WSTH w Łodzi: Łódź, Poland, 2010; pp. 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Minnaert, L. Social tourism participation: The role of tourism inexperience and uncertainty. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches—Towards a new generation concept? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, J. Agroturystyka—Signum polskiej turystyki. Acta Sci. Polonorum. Oeconomia 2010, 9, 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Konečný, O. Geographical perspectives on agritourism in the Czech Republik. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2014, 22, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tolstad, H.K. Development of rural-tourism experiences through networking: An example from Gudbrandsdalen, Norway. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Nor. J. Geogr. 2014, 68, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajgier-Kowalska, M.; Tracz, M.; Uliszak, R. Modeling the state of agritourism in the Malopolska region of Poland. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 502–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoian, M.; Marcuta, A.; Niculae, I.; Marcuta, L. Analysis of agritourism and rural tourism situation in the North East of Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2019, 19, 535–542. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.; Connell, J. ‘Bongo Fury’: Tourism, music and cultural economy at Byron Bay, Australia. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2003, 94, 164–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottola, P. The metaspatialities of control management in tourism: Backpacking in India. Tour. Geogr. 2005, 7, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argent, N. Trouble in paradise? Governing Australia’s multifunctional rural landscapes. Aust. Geogr. 2011, 42, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. Rural tourism and sustainable rural tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, L. Sustainable tourism systems: The example of sustainable rural tourism in Sweden. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, I.C.; Oroian, C.F.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Porutiu, A.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Lile, R. Local residents’ attitude toward sustainable rural tourism development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantar, S.; Svržnjak, K. Development of Sustainable Rural Tourism. Deturope 2017, 9, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffe, X. Is rural tourism a lever for economic and social development? J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, A. Rural tourism as a factor in rural community economic development for economies in transition. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirela, C.S. Agrotourism and gastronomic tourism, parts of sustainable tourism. J. Hortic. For. Biotechnol. 2016, 20, 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- Fons, M.V.S.; Fierro, J.A.M.; Patiño, M.G. Rural tourism: A sustainable alternative. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdak, P.; de Almeida, A.M.M. Pre-Emptively Managing Overtourism by Promoting Rural Tourism in Low-Density Areas: Lessons from Madeira. Sustainability 2022, 14, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedziółka, A.; Bogusz, M. Uwarunkowania rozwoju turystyki społecznej na przykładzie gminy Istebna. Folia Pomeranae Univ. Technol. Stetinensis Oeconomica 2011, 288, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.C. Religious tourism and its management: The hajj in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowski, A. Pielgrzymki = turystyka pielgrzymkowa = turystyka religijna? Rozważania terminologiczne. Turyzm 1998, 8, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowski, A. Pielgrzymki zagraniczne szansą dla rozwoju polskich ośrodków kultu religijnego. Pr. Geogr. 2007, 117, 239–257. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, F.; Mróz, Ł. Nowe trendy w turystyce religijnej. In Współczesne Uwarunkowania i Problemy Rozwoju Turystyki; Pawlusiński, R., Ed.; Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ: Kraków, Poland, 2013; pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, F. Pielgrzymki i turystyka religijna w Polsce po transformacji ustrojowej 1989 r. Geogr. Inf. 2014, 2, 124–237. [Google Scholar]

- Bik, J.; Stasiak, A. World Youth Day 2016 in the Archdiocese of Lodz: An Example of the Eventization of Faith. Religions 2020, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.T.V.; Mariz, C.L.; Zahra, A. World Youth Day: Contemporaneous pilgrimage and hospitality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendel, T. Foot-pilgrims and backpackers: Contemporary ways of travelling. Scr. Inst. Donneriani Abo. 2010, 22, 288–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Wang, K.Y.; Lin, S.Y. When backpacker meets religious pilgrim house: Interpretation of oriental folk belief. J. Study Relig. Ideol. 2012, 11, 76–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kotze, N.; McKay, T. South Africans Walking the Camino: Pilgrimage or Adventure. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 997–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, B.W. Bicycle tourism in the South Island of New Zealand: Planning and management issues. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, M. Reinventing the wheel: A definitional discussion of bicycle tourism. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śledzińska, J.; Włodarczyk, B. (Eds.) Turystyka Rowerowa w Zjednoczonej Europie; Wydawnictwo PTTK „Kraj”: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; pp. 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, J.H. Urban bicycle tourism: Path dependencies and innovation in Greater Copenhagen. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, W.; Mika, M.; Pitrus, E. Formy turystyki kwalifikowanej. In Turystyka; Kurek, W., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; pp. 256–278. [Google Scholar]

- Buning, R.J.; Gibson, H.J. The role of travel conditions in cycling tourism: Implications for destination and event management. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, P.; Jorgenson, B. Cycle Tourism: An Economic and Environmental Sustainable Form of Tourism? Unit of Tourism Research, Research Centre of Bornholm: Bornholm, Denmark, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Meschik, M. Sustainable cycle tourism along the Danube Cycle Route in Austria. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2012, 9, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Grechi, D.; Ossola, P. Cycle tourism as a driver for the sustainable development of little-known or remote territories: The experience of the Apennine regions of northern Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Młodzik, M.; León-Guereño, P.; Adamczewska, K. Male and female motivations for participating in a mass cycling race for amateurs: The skoda bike challenge case study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Hall, C.M. Bicycle tourism and regional development: A New Zealand case study. Anatolia 1999, 10, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearing, S. Volunteer Tourism: Experiences that Make a Difference; Cab: Wallingford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wearing, S.; McGehee, N.G. Volunteer tourism: A review. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D.A. The possible negative impacts of volunteer tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, P. I’m Not Looking for a Manufactured Experience’: Calling for a Decommodified Volunteer Tourism ’CAUTHE 2017. In Time for Big Ideas-Rethinking the Field for Tomorrow, Paper Presented at the 27th Annual CAUTHE Conference, Dunedin, New Zealand, 7–10 February 2017; The University of Newcastle: Callaghan, Australia, 2017; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tomazos, K.; Butler, R. Volunteer tourism: Tourism, serious leisure, altruism or self enhancement? In Where the Bloody Hell are We? Proceedings of the CAUTHE 2008 Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 11–14 February 2008; Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management, University of Strathclyde: Glasgow, UK, 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, A.J.; Zahra, A. A cultural encounter through volunteer tourism: Towards the ideals of sustainable tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Zhang, J.J. Rethinking sustainability in volunteer tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1820–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Rohrscheidt, A.M. Turystyka społeczna—Geneza i istota. Cvncvnvnvn. In Turystyka Społeczna w Polsce. Przewodnik Dobrych Praktyk; Stasiak, A., Ed.; Oficyna Wydawnicza Wierchy: Kraków-Świdnica, Poland, 2021; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

| Stage of Review Procedure | Details |

|---|---|

| First stage | Selection of the article research question |

| Second stage | Selection of bibliographic databases for the literature analysis |

| Third stage | Selection of specific keywords (terms) and preliminary search of online databases for scientific publications (resulted in 203 different publications) |

| Fourth stage | Further scaning of the preliminarily selected publications to find the studies most relevant to the article (resulted in 112 publications qualified for the further detailed analysis) |

| Fifth stage | In-depth review of the selected 112 publications relevant to the topic of this article, synthesis and presentation of the research results |

| Journal Papers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Journal | Number of Publications Used in the Article | Research Field | Frequency (Issues per Year) |

| Journal of Sustainable Tourism | 12 | Tourism, sustainability | 12 |

| Annals of Tourism Research | 6 | Tourism | 6 |

| Sustainability | 9 | Sustainable development | 24 |

| Tourism Management | 4 | Tourism, management | 6 |

| International Journal of Tourism Research | 3 | Tourism | 6 |

| Tourism | 3 | Tourism | 2 |

| Current Issues in Tourism | 2 | Tourism | 24 |

| Journal of Sport & Tourism | 2 | Sports, tourism | 4 |

| Tourism Geographies | 2 | Tourism, geography | 5 |

| Turizam | 2 | Tourism | 4 |

| Applied Energy | 1 | Energy research | |

| Journal of Horticulture, Forestry and Biotechnology | 1 | Horticulture, genetics, plants breeding, plants, forests | 4 |

| Acta Scientiarum Polonorum. Oeconomia | 1 | Economics | 4 |

| Anatolia | 1 | Tourism | 4 |

| Asien Afrika Latinamerica | 1 | Regions of Asia, Latin America, Africa | 6 |

| Australian Geographer | 1 | Geography, regional development | 4 |

| Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov. Economic Sciences. Series V | 1 | Economics, finance, marketing, tourism, management | 2 |

| Deturope | 1 | Regional development, tourism | 3 |

| Ekonomiczne Problemy Turystyki | 1 | Tourism economics | 4 |

| Folia Pomeranae Universitatis Technologiae Stetinensis. Oeconomica | 1 | Economics, social sciences | 4 |

| Geografické informácie | 1 | Economic geography, regional development | 2 |

| Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites | 1 | Geography, tourism | 4 |

| Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies | 1 | Religious studies | 3 |

| Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management | 1 | Tourism, hospitality, management, marketing | 6 |

| Moravian Geographical Reports | 1 | Geography, regional development | 4 |

| Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift-Norwegian Journal of Geography | 1 | Geography, regional development | 5 |

| Prace Geograficzne | 1 | Geography, regional development | 4 |

| Religions | 1 | Religious studies | 12 |

| Scientific Papers. Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development | 1 | Agriculture, rural management and development | 4 |

| Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis | 1 | Religious studies | 1 |

| Social Research | 1 | Social sciences | 4 |

| The Geographical Journal | 1 | Geography, regional development | 4 |

| Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie | 1 | Geography, regional development | 5 |

| African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure | 1 | Hospitality, tourism, leisure | 5 |

| Tourism Management Perspectives | 1 | Tourism management | 4 |

| Tourism Planning & Development | 1 | Tourism development, tourism management, regional development | 6 |

| Tourism Recreation Research | 1 | Tourism, leisure, recreation | 4 |

| Tourism Review | 1 | Tourism | 6 |

| Tourist Studies | 1 | Tourism | 4 |

| Travel & Tourism Analyst | 1 | Tourism | 6 |

| Journal of Business Research | 1 | Business research | 16 |

| Sustainability Science | 1 | Sustainable development | 6 |

| Ecological Indicators | 1 | Environmental studies, sustainable development | 14 |

| Books | |||

| Publisher | Number of publications used in the article | ||

| PWN | 5 | ||

| CABI | 3 | ||

| Chanell View Publication | 2 | ||

| PWE | 2 | ||

| Routledge | 2 | ||

| Springer | 2 | ||

| Universe Books | 1 | ||

| University of Heidelberg | 1 | ||

| UNWTO | 1 | ||

| WSTH w Łodzi | 1 | ||

| Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej w Poznaniu | 1 | ||

| Wydawnictwo PTTK Kraj | 1 | ||

| Earth Policy Institute | 1 | ||

| Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego | 1 | ||

| Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ | 1 | ||

| Lanham University Press of America | 1 | ||

| Oficyna Wydawnicza Wierchy | 1 | ||

| Oxford University Press | 1 | ||

| Sage | 2 | ||

| Conference papers | |||

| Publisher | Number of publications used in the article | ||

| Annual CAUTHE Conference | 2 | ||

| Unit of Tourism Research, Research Centre of Bornholm | 1 | ||

| Websites | |||

| https://www.unwto.org/tourism-in-2030-agenda accessed on 1 August 2022 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Pillars of sustainable tourism according to | Features of low-cost tourism types responsible for realization of the sustainability pillars presented in column 1 | Types of low-cost tourism representing the features from column 2 |

| Environmental |

| Backpacking Youth tourism Cycling tourism Rural/agritourism |

| Characteristics Protecting the sources of raw materials and other natural resources; reduction and assimilation of waste, pollution, and CO2 emmissions; sustaining the biosphere and biological diversity; sustaining the biogeochemical integrity of the biosphere by conservation and responsible use of air, water, and land resources, etc. | ||

| Social |

| Backpacking Rural/agritourism Volunteer tourism Social tourism |

| Characteristics Preserving the social and cultural values, identities, relationships, and institutions for the future; upholding human wellbeing in a healthy environment and vibrant economy; sustaining social justice and developing equity among people, regions, and nations, etc. | ||

| Economic |

| Backpacking Youth tourism Rural/agritourism Volunteer tourism Cycling tourism Social tourism Pilgrimage tourism |

| Characteristics Sustaining economically important natural resources for the use of future generations; prolonging responsible and sustainable economic growth over a long time; sustaining economic well-being at different levels of society and in different regions and localities, etc. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Włodarczyk, B.; Cudny, W. Individual Low-Cost Travel as a Route to Tourism Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710514

Włodarczyk B, Cudny W. Individual Low-Cost Travel as a Route to Tourism Sustainability. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710514

Chicago/Turabian StyleWłodarczyk, Bogdan, and Waldemar Cudny. 2022. "Individual Low-Cost Travel as a Route to Tourism Sustainability" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710514

APA StyleWłodarczyk, B., & Cudny, W. (2022). Individual Low-Cost Travel as a Route to Tourism Sustainability. Sustainability, 14(17), 10514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710514