Progress and Prospects of Destination Image Research in the Last Decade

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Destination Image

1.2. Status of the Reviewed Literature

1.2.1. Literature Sources

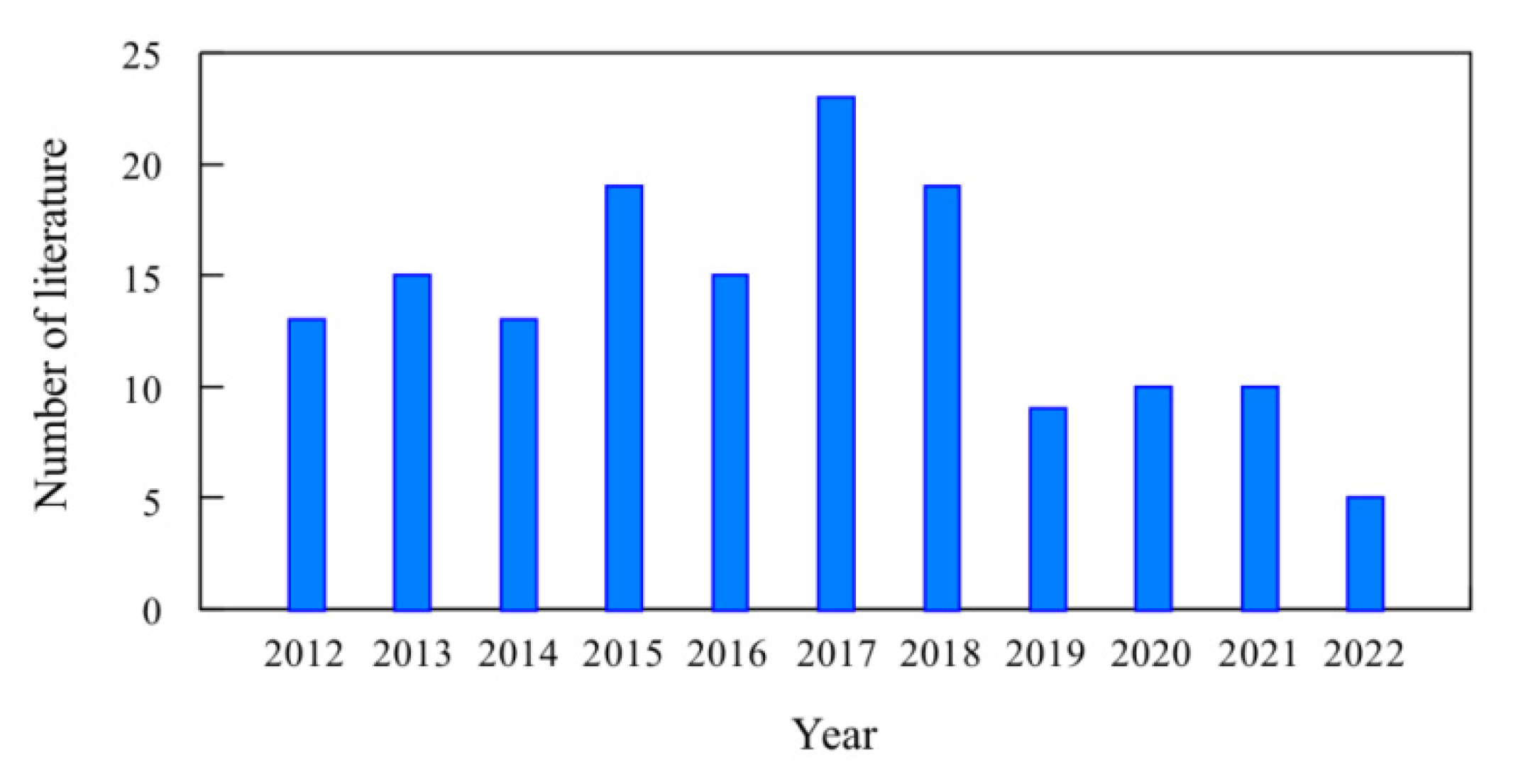

1.2.2. Literature Characteristics

2. Structure of the Destination Image

3. Destination Image Measurement and Branding

3.1. Destination Image Measurement Methods

3.2. Destination Image Branding

4. Influencing Factors of Destination Image

4.1. The Influential Role of Individual Factors

4.2. The Influential Role of Information Sources

5. The Influence of Destination Image on Consumer Behavior

5.1. The Influence of Destination Image on Pre-Travel Behavior

5.2. The Influence of Destination Image on Tourist Behavior during Tourism

5.3. The Influence of Destination Image on Post-Travel Behavior

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Perspectives

6.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herzog, H. Behavioral science concepts for analyzing the consumer. Mark. Behav. Sci. 1963, 3, 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J.L. An Assessment of the Image of Mexico as a Vacation Destination and the Influence of Geographical Location upon That Image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Richardson, S.L. Motion picture impacts on destination images. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martín, J.D. Tourists’ characteristics and the perceived image of tourist destinations: A quantitative analysis—A case study of Lanzarote, Spain. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G. Examining a hierarchical model of Australia’s destination image. J. Vacat. Mark. 2014, 20, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G.; Woo, L.; Kock, F. The imagery–image duality model: An integrative review and advocating for improved delimitation of concepts. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Deng, N.; Li, X.; Gu, H. How to “read” a destination from images? Machine learning and network methods for DMOs’ image projection and photo evaluation. J. Travel Res. 2021, 61, 597–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embacher, J.; Buttle, F. A Repertory Grid Analysis of Austria’s Image as a Summer Vacation Destination. J. Travel Res. 1989, 27, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M.S. Tourists’ Images of a Destination—An Alternative Analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1996, 5, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. Destination Image. Destination Marketing Organizations, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; Volume 5, pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu, S.; Brinberg, D. Affective images of tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 1997, 35, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.E.; Andreu, L.; Gnoth, J. The theme park experience: An analysis of pleasure, arousal and satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Zehrer, A.; Müller, S. Perceived destination image: An image model for a winter sports destination and its effect on intention to revisit. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1993, 2, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The distinction between desires and intentions. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. The self–regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G.; Dubelaar, C.A. General theory of tourism consumption systems: A conceptual framework and an empirical exploration. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Ryan, C. Destination positioning analysis through a comparison of cognitive, affective, and conative perceptions. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Tourists’ evaluations of destination image, satisfaction, and future behavioral intentions—The case of Mauritius. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 836–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.; Chen, N.; Funk, D.C. Exploring destination image decay: A study of sport tourists’ destination image change after event participation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestwich, A.; Perugini, M.; Hurling, R. Goal desires moderate intention–behaviour relations. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, C.J. Ideal standards and attitude formation: A tourism destination perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Cai, L.A.; Lu, L. Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta–analysis. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Ye, B.H.; Xiang, J. Reality TV, audience travel intentions, and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylos, N.; Bellou, V.; Andronikidis, A.; Vassiliadis, C.A. Linking the dots among destination images, place attachment, and revisit intentions: A study among British and Russian tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaansen, M.; Straatman, S.; Mitas, O.; Stekelenburg, J.; Jansen, S. Emotion measurement in tourism destination marketing: A comparative electroencephalographic and behavioral study. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Stylidis, D.; Ivkov, M. Explaining conative destination image through cognitive and affective destination image and emotional solidarity with residents. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.Y.; Wang, Y.; Khoo–Lattimore, C. Do food image and food neophobia affect tourist intention to visit a destination? The case of Australia. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 928–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Shani, A.; Belhassen, Y. Testing an integrated destination image model across residents and tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, D.; Apostolopoulou, A.; Kaplanidou, K. Destination personality, affective image, and behavioral intentions in domestic urban tourism. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshardoost, M.; Eshaghi, M.S. Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta–analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S.S. Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G. Advancing destination image: The destination content model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Jin, X.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Urban air pollution in China: Destination image and risk perceptions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T.; Feng, S.F. Authenticity: The link between destination image and place attachment. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.C.Y.; Mak, A.H.N. Understanding gastronomic image from tourists’ perspective: A repertory grid approach. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L. The Core–Periphery Structure of Internationalization Network in the Tourism Sector. J. China Tour. Res. 2011, 7, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Xiang, R.L. Chinese Outbound Tourists’ Destination Image of America: Part II. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, K.W.; Merritt, R.L. Effects of Events on National and International Images. In International Behavior: A Social–Psychological Analysis; Kelman, H.C., Ed.; Yale University: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 87–132. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, K.; Li, Y.P. Core–Periphery Structure of Destination Image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1359–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Lai, K. A meeting of the minds: Exploring the core–periphery structure and retrieval paths of destination image using social network analysis. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The meaning and measurement of destination image. J. Tour. Stud. 1991, 2, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu, S.; Love, C. Association meeting planners’ perceptions and intentions for five major US convention cities: The structured and unstructured images. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Grün, B. Validly measuring destination image in survey studies. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, M.; Morgan, N.J. Reconstruing place image: A case study of its role in destination market research. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Li, X.R. The long tail of destination image and online marketing. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Sit, J.; Biran, A. An exploratory study of residents’ perception of place image: The case of Kavala. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín–Santana, J.D.; Beerli–Palacio, A.; Nazzareno, P.A. Antecedents and consequences of destination image gap. Annals of Tourism Research 2017, 62, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. Residents’ place image: A cluster analysis and its links to place attachment and support for tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Peng, N. Examining consumers’ intentions to dine at luxury restaurants while traveling. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S.S. Development and validation of a multidimensional tourist’s local food consumption value (TLFCV) scale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Martin, G.E. Models of Core/Periphery Structures. Soc. Netw. 2000, 21, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.; Ritchie, J.R. The measurement of destination image: An empirical assessment. J. Travel Res. 1993, 31, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Stepchenkova, S. Chinese outbound tourists’ destination image of America: Part I. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.; Dias, F.; de Araújo, A.F.; Marquesa, M.I.A. A destination imagery processing model: Structural differences between dream and favourite destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Li, X.R. Destination image: Do top–of–mind associations say it all? Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 45, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R.; Go, F.M.; Kumar, K. Virtual destination image a new measurement approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 977–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Gartner, W.C.; Cavusgil, S.T. Conceptualization and operationalization of destination image. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2007, 31, 194–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Zhan, F. Visual destination images of Peru: Comparative content analysis of DMO and user–generated photography. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, X.; Ryan, C. Perceiving tourist destination landscapes through Chinese eyes: The case of South Island, New Zealand. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.N. Online destination image: Comparing national tourism organisation’s and tourists’ perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paivio, A.; Rogers, T.B.; Smythe, P.C. Why are pictures easier to recall than words? Psychon. Sci. 1968, 11, 137–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Ekinci, Y.; Uysal, M. Destination image and destination personality: An application of branding theories to tourism places. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Lee, J.; Tsai, H. Travel photos: Motivations, image dimensions, and affective qualities of places. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Stepchenkova, S. Effect of tourist photographs on attitudes towards destination: Manifest and latent content. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Qu, H.; Hsu, M.K. Toward an integrated model of tourist expectation formation and gender difference. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.J.; Wang, P. All that’s best of dark and bright: Day and night perceptions of Hong Kong cityscape. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, C.; Levy, S.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Destination branding: Insights and practices from destination management organizations. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, S.; Busser, J.; Baloglu, S. A model of customer–based brand equity and its application to multiple destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneesel, E.; Baloglu, S.; Millar, M. Gaming destination images: Implications for branding. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecnik, M.; Gartner, W.C. Customer–based brand equity for a destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsi, F.; Pike, S.; Gottlieb, U. Consumer–based brand equity (CBBE) in the context of an international stopover destination: Perceptions of Dubai in France and Australia. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Pike, S.; Lings, I. Investigating attitudes towards three South American destinations in an emerging long haul market using a model of consumer–based brand equity (CBBE). Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Fernández, A.C.; Gómez, M.; Aranda, E. Differences in the city branding of European capitals based on online vs. offline sources of information. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S. Reconstructing the place branding model from the perspective of Peircean semiotics. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martin, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S. When Middle East meets West: Understanding the motives and perceptions of young tourists from United Arab Emirates. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Kim, H.; Kirilenko, A. Cultural differences in pictorial destination images: Russia through the camera lenses of American and Korean tourists. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, J.; Gidlow, B.; Fisher, D. National stereotypes in tourist guidebooks: An analysis of auto–and hetero–stereotypes in different language guidebooks about Switzerland. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L.S.; Nyaupane, G.P. The tourist gaze: Domestic versus international tourists. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 877–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Lai, Y.H.R.; Petrick, J.F.; Lin, Y.H. Tourism between divided nations: An examination of stereotyping on destination image. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; O’Connor, P. eWOM platforms in moderating the relationships between political and terrorism risk, destination image, and travel intent: The case of Lebanon. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.; Tung, V.W.S. Understanding residents’ attitudes towards tourists: Connecting stereotypes, emotions and behaviours. Tour. Manag. 2022, 89, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Chen, P.J.; Okumus, F. The relationship between travel constraints and destination image: A case study of Brunei. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, T.F.; Gnoth, J.; Deans, K.R. Localizing cultural values on tourism destination websites: The effects on users’ willingness to travel and destination image. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Belhassen, Y.; Shani, A. Three tales of a city: Stakeholders’ images of Eilat as a tourist destination. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chi, C.G.Q.; Xu, H. Developing destination loyalty: The case of Hainan Island. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.S.; Liu, C.H.; Chou, H.Y.; Tsai, C.Y. Understanding the impact of culinary brand equity and destination familiarity on travel intentions. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. The impact of memorable tourism experiences on loyalty behaviors: The mediating effects of destination image and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Cole, M., John–Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Tasci, A.D.A. The effect of resident–tourist interaction quality on destination image and loyalty. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 30, 1219–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. Exploring resident–tourist interaction and its impact on tourists’ destination image. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.; Tung, V.W.S. Measuring the Valence and Intensity of Residents’ Behaviors in Host–Tourist Interactions: Implications for Destination Image and Destination Competitiveness. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llodrà–Riera, I.; Martínez–Ruiz, M.P.; Jiménez–Zarco, A.I.; Yusta, A.I. A multidimensional analysis of the information sources construct and its relevance for destination image formation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camprubí, R.; Coromina, L. The role of information sources in image fragmentation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Lockshin, L. Reverse country–of–origin effects of product perceptions on destination image. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, M.; Collins, M.D.; Jones, D.L. Exploring the relationship between destination image, aggressive street behavior, and tourist safety. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltes–Dorta, A.; Rodríguez–Déniz, H.; Suau–Sanchez, P. Passenger recovery after an airport closure at tourist destinations: A case study of Palma de Mallorca airport. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuring, J.H.G. Weather perceptions, holiday satisfaction and perceived attractiveness of domestic vacationing in The Netherlands. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilynets, I.; Knezevic Cvelbar, L.; Dolnicar, S. Can publicly visible pro–environmental initiatives improve the organic environmental image of destinations? J. Sustain. Tour. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessitore, T.; Pandelaere, M.; Van Kerckhove, A. The Amazing Race to India: Prominence in reality television affects destination image and travel intentions. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Ryan, C. Interpretation, film language and tourist destinations: A case study of Hibiscus Town, China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 334–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W.C. China’s Chairman Mao: A visual analysis of Hunan Province online destination image. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Bai, B. Influence of popular culture on special interest tourists’ destination image. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, J.L.; Sharma, A.; Shin, S. The tourism effect of President Trump’s participation on Twitter. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Hallab, Z.; Kim, J.N. The moderating effect of travel experience in a destination on the relationship between the destination image and the intention to revisit. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamustafa, K.; Fuchs, G.; Reichel, A. Risk perceptions of a mixed–image destination: The case of Turkey’s first–time versus repeat leisure visitors. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.W.; Li, X.R.; Pan, B.; Witte, M.; Doherty, S.T. Tracking destination image across the trip experience with smartphone technology. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chi, C.G.; Liu, Y. Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Gollan, T.; Van Quaquebeke, N. Using polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology to make a stronger case for value congruence in place marketing. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; von Wallpach, S.; Braun, E.; Vallaster, C. How the refugee crisis impacts the decision structure of tourists: A cross–country scenario study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, A.; Stacchini, A.; Costa, M. Can sustainability drive tourism development in small rural areas? Evidences from the Adriatic. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 30, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.H.; Wen, J.C.; Chiung, Y.C. Destination Image Analysis and its Strategic Implications: A Literature Review from 1990 to 2019. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Rev. 2021, 8, 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G. Look at me—I am flying: The influence of social visibility of consumption on tourism decisions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hultman, M.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Wei, X.J. How does brand loyalty interact with tourism destination? Exploring the effect of brand loyalty on place attachment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 81, 102879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veasna, S.; Wu, W.Y.; Huang, C.H. The impact of destination source credibility on destination satisfaction: The mediating effects of destination attachment and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Phou, S. A closer look at destination: Image, personality, relationship and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; McCabe, S. Expanding theory of tourists’ destination loyalty: The role of sensory impressions. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.T.; Jahari, S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post–disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylos, N.; Vassiliadis, C.A.; Bellou, V.; Andronikidis, A. Destination images, holistic images and personal normative beliefs: Predictors of intention to revisit a destination. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; da Silva, R.V.; Antova, S. Image, satisfaction, destination and product post–visit behaviours: How do they relate in emerging destinations? Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Uslu, A.; Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M. Place–oriented or people–oriented concepts for destination loyalty: Destination image and place attachment versus perceived distances and emotional solidarity. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L. The effects of environmental and luxury beliefs on intention to patronize green hotels: The moderating effect of destination image. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 904–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; He, J.; Gu, Y. The implicit measurement of destination image: The application of Implicit Association Tests. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Bordelon, B.M.; Pearlman, D.M. Destination–image recovery process and visit intentions: Lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W.C. The social construction of tourism online destination image: A comparative semiotic analysis of the visual representation of Seoul. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Li, X.R. Feeling a destination through the “right” photos: A machine learning model for DMOs’ photo selection. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefieva, V.; Egger, R.; Yu, J. A machine learning approach to cluster destination image on Instagram. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toral, S.L.; Martínez–Torres, M.R.; Gonzalez–Rodriguez, M.R. Identification of the unique attributes of tourist destinations from online reviews. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Rasouli, S.; Timmermans, H. Investigating tourist destination choice: Effect of destination image from social network members. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannassee, R.V.; Seetanah, B. The influence of trust on repeat tourism: The Mauritian case study. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 770–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Jang, S. Information value and destination image: Investigating the moderating role of processing fluency. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 790–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez–Molina, M.A.; Frías–Jamilena, D.M.; Castañeda–García, J.A. The contribution of website design to the generation of tourist destination image: The moderating effect of involvement. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Kuo, B.Z.L. The moderating effects of travel arrangement types on tourists’ formation of Taiwan’s unique image. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potwarka, L.R.; Banyai, M. Autonomous agents and destination image formation of an Olympic Host city: The case of Sochi 2014. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.K.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, J. Dynamic nature of destination image and influence of tourist overall satisfaction on image modification. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, G.Y.; Gursoy, D.; Fu, X.R. Message framing and regulatory focus effects on destination image formation. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; Hallak, R. Moderating Effects of Tourists’ Novelty-Seeking Tendencies on Destination Image, Visitor Satisfaction, and Short- and Long-Term Revisit Intentions. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Authors |

|---|---|

| Structural method | Lai et al., 2020; Stylidis et al., 2017; Echtner and Ritchie, 1991; Stylidis, 2018; Chen and Peng, 2018; Echtner and Ritchie, 1993; Wang et al., 2016; Stepchenkova et al., 2015; Bender, 2013; Karamustafa et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2015; Line and Hanks, 2016; Yang et al., 2012; |

| Structural method + non-structural method | Becken et al., 2017; Stylidis et al., 2016; Martín–Santana et al., 2017; Choe and Kim, 2019; Huang and Wang, 2018; Stone and Nyaupane, 2019; Stylidis et al., 2015; Llodrà–Riera et al., 2015; Hao and Ryan, 2013; Hunter, 2013; Ryu et al., 2013; Toral et al., 2018; |

| Non-structural method | He et al., 2021; Bastiaansen et al., 2022; Liang, 2011; Borgatti and Martin, 2000; Cardoso et al., 2019; Stepchenkova and Li, 2014; Govers et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2015; Mak, 2017; Paivio et al., 1968; Blain et al., 2005; Boo et al., 2009; Hunter, 2016; Deng and Li, 2018; Arefieva et al., 2021; |

| Influencing Factors | Authors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals factors | Travel motivation | Pan et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016; Prayag and Hosany, 2014; | |

| Cultural background | Sun et al., 2015; Prayag and Hosany, 2014; Stepchenkova et al., 2015; Bender et al., 2013; Stone and Nyaupane, 2019; Chen et al., 2016; Assaker and O’Connor, 2021; Tse and Tung, 2022; Chen et al., 2013; Moura, 2015; | ||

| Demographic variables | Wang et al., 2016; Stylidis et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2021; | ||

| Destination familiarity | Sun et al., 2013; Horng et al., 2012; | ||

| Personal experience | Kim, 2018; Stylidis et al., 2021; Stylidis, 2022; Tse and Tung, 2022; | ||

| Trust | Sannassee and Seetanah, 2015; | ||

| Information source factors | Second-hand | Destination promotional materials | Sun et al., 2015; Llodrà–Riera et al., 2015; Lee and Lockshin, 2012; Millar et al., 2017; Voltes–Dorta et al., 2017; Jeuring, 2017; Bilynets et al., 2021; Lin and Kuo, 2018; |

| Social media | Martín–Santana et al., 2017; Stepchenkova and Zhan, 2013; Kim and Stepchenkova, 2015; Camprubí and Coromina, 2016; Tang and Jang, 2014; Rodríguez–Molina et al., 2015; | ||

| TV and movies | Zhang et al., 2014; Tessitore et al., 2014; Hao and Ryan, 2013; | ||

| Public figures | Hunter, 2013; Lee and Bai, 2016; Nicolau et al., 2020; | ||

| News | Potwarka and Banyai, 2016; | ||

| First-hand | Experiences | Cardoso et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2012; Karamustafa et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2014; | |

| Perception | Lu et al., 2015; Zenker et al., 2019; Guizzardi et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2018; | ||

| Author (Year) | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Path Relations Containing Image Variables | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of Variable | Measurement Indicators | |||

| 1. Josiassen and Assaf (2013) | A, B, C | Travel decision | ①, ② | A + B + C→① + ② |

| 2. Fu et al. (2016) | A1, A2, D | Travel intention | ② | D→A1→③; D→A2→③; D→A1→A2→③; D→③ |

| 3. Lai et al. (2020) | A1, A2 | Intention to visit | ④ | A1→④; A1 a→A2→④ |

| 4. Jiang et al. (2017) | A, E | Place attachment | ⑤, ⑥, ⑦, ⑧ | A→E→⑤ + ⑥ + ⑦ + ⑧ |

| 5. Liu et al. (2020) | A2, F, G, H2 | Place attachment | ⑨, ⑩ | F→A2; F + G→A2; G + H2→b A2; F→A2→⑨ + ⑩ |

| 6. Kim et al. (2012) | A, I | Intention to revisit | ⑪ | I→A→⑪ |

| 7. Prayag and Ryan (2012) | A, D, J, K | Loyalty | ⑪, ⑫ | D→A→J→K→⑪ + ⑫; D→A→K→⑪ + ⑫ |

| 8. Veasna et al. (2013) | A, J, L | Satisfaction | ⑬ | L→A→J→⑬ |

| 9. Sun et al. (2013) | A, K, M, N | Loyalty | ⑪, ⑫ | M→A→N→K→⑪ + ⑫; M→A→K→⑪ + ⑫ |

| 10. Chen and Phou (2013) | A, J, K, O, P | Loyalty | ⑪, ⑫ | A→K→⑪ + ⑫; A→K→P→J→⑪ + ⑫; A→P→J→⑪ + ⑫; A→O→P→J→⑪ + ⑫ |

| 11. Assaker and Hallak (2013) | A, K, Q | Intention to revisit | ⑪ | Q→A→K→⑪ |

| 12. Chew and Jahari (2014) | A1, A2, R2, R3 | Intention to revisit | ⑪ | R2→A1→⑪; R2→A2→⑪; R3→A1→⑪; R3→A2→⑪ |

| 13. Hallmann et al. (2015) | A1, A2, A4 | Intention to revisit | ⑪ | A1 + A2→A4→⑪ |

| 14. Stylos et al. (2016) | A2, A3, A4, S | Intention to revisit | ⑪ | A2→A4→⑪; A3→⑪; S→A3→A4→⑪ |

| 15. Stylos et al. (2017) | A1, A2, A3, A4 | Intention to revisit | ⑪ | A1→A4→⑪; A2→A4→⑪; A3→A4→⑪; A3→⑪ |

| 16. Stylidis et al. (2017) | A1, A2, A4 | Willingness to recommend | ⑫ | A1→A2; A1→A4→⑫; A2→A4→⑫; A1→⑫; A2→⑫ |

| 17. Kim (2018) | A, K, T | Loyalty | ⑪, ⑭ | A→⑪ + ⑭; T→A→⑪ + ⑭; T→A→K→⑪ + ⑭ |

| 18. Lv and McCabe (2020) | A, K, N, U, V | Loyalty | ⑪, ⑫ | A→⑪ + ⑫; A→K→⑪ + ⑫; A→N→⑪ + ⑫; A→V→⑪ + ⑫; U→⑪ + ⑫; U→K→⑪ + ⑫; U→N→⑪ + ⑫; U→V→⑪ + ⑫ |

| 19. Marques et al. (2021) | A1, A2, A5, K | Loyalty | ⑫, ⑮ | A1→⑫→⑮; A2→K; K→⑫→⑮; A2→⑫→⑮; A5→⑮ |

| 20. Tasci et al. (2022) | A1, A2, J1, J2, H2, W3 | Loyalty | ⑪, ⑫ | A1 + A2→J1 + J2; J1 + J2→⑪ + ⑫; A1 + A2→J1 + J2→⑪ + ⑫; H2→c W3; W3→⑪ + ⑫; H2→c W3→⑪ + ⑫ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, Q.; Bao, G.; Sun, J. Progress and Prospects of Destination Image Research in the Last Decade. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10716. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710716

Chu Q, Bao G, Sun J. Progress and Prospects of Destination Image Research in the Last Decade. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10716. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710716

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Qi, Guang Bao, and Jiayu Sun. 2022. "Progress and Prospects of Destination Image Research in the Last Decade" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10716. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710716

APA StyleChu, Q., Bao, G., & Sun, J. (2022). Progress and Prospects of Destination Image Research in the Last Decade. Sustainability, 14(17), 10716. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710716