The Heritage Jewel of Saudi Arabia: A Descriptive Analysis of the Heritage Management and Development Activities in the At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah, a World Heritage Site (WHS)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- to map out the change over time of Historic Diriyah before it was inscribed to UNESCO and after;

- to examine Historic Diriyah heritage management practices and development impact through three aspects of analysis: physical, social, and economic;

- to analyzes the influence of the inscription of Historic Diriyah to the UNESCO World Heritage List on the field of heritage in Saudi Arabia.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. World Heritage Sites WHS

2.2. Sustainable Urban Development

2.3. Sustainable Urban Development in the Context of WHS

3. Research Design and Methodology

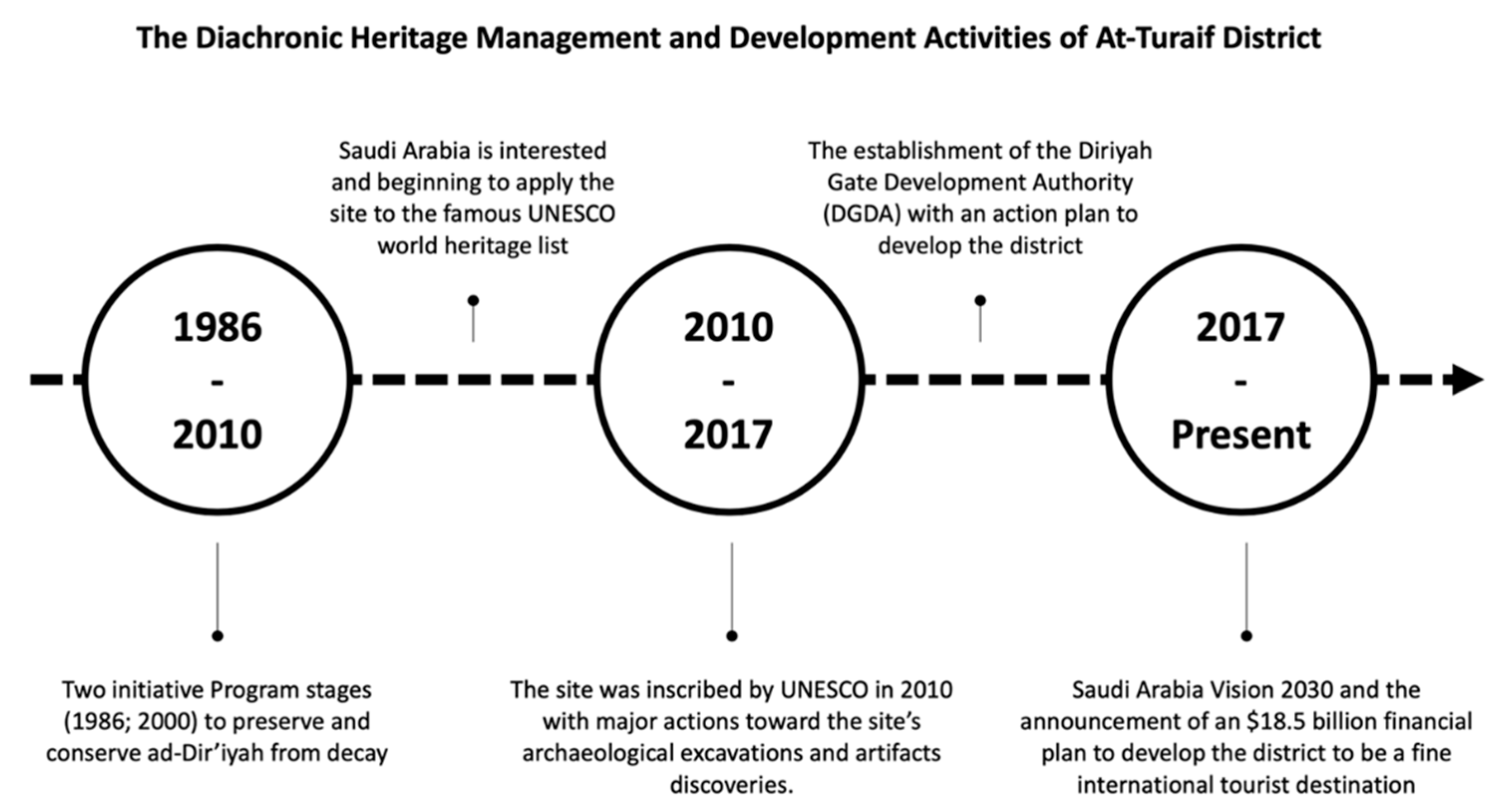

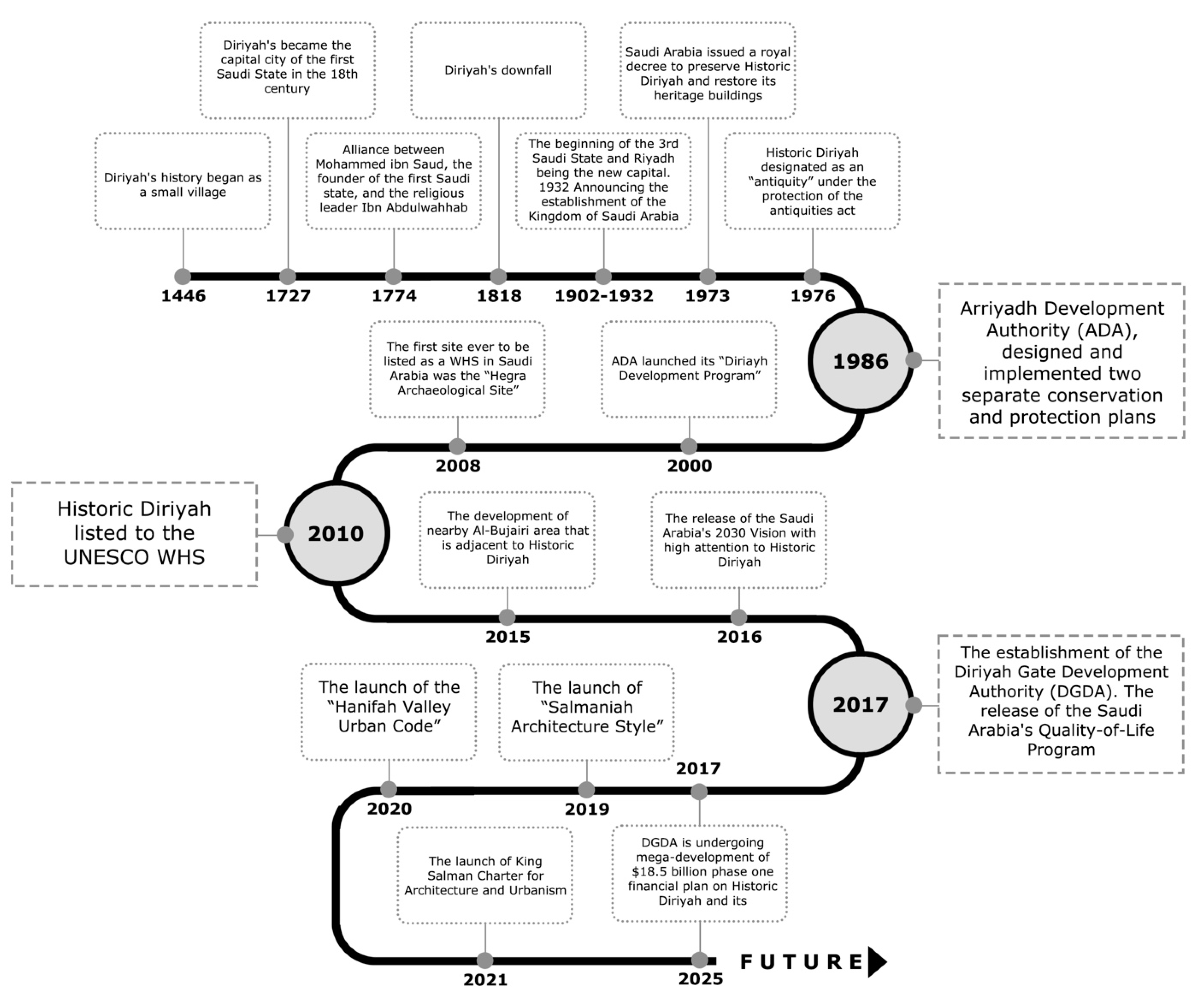

4. The Diachronic Heritage Management and Development Activities of At-Turaif

4.1. Heritage Conservation and Development before 2010: From Social Migration and Physical Decay to Ruins’ Protection and Developmental Ideation

4.2. Heritage Conservation and Development after 2010 until 2017: WHS Inscription and Implementation Plan

- Being non-intrusive: to ensure old and new structures are compatible; intervention strategies should be minimal, distinguishing between old and new additions and repair.

- Ensuring reversibility: conservation interventions should be reversible without damaging the original structure.

- Use of original materials and traditional techniques.

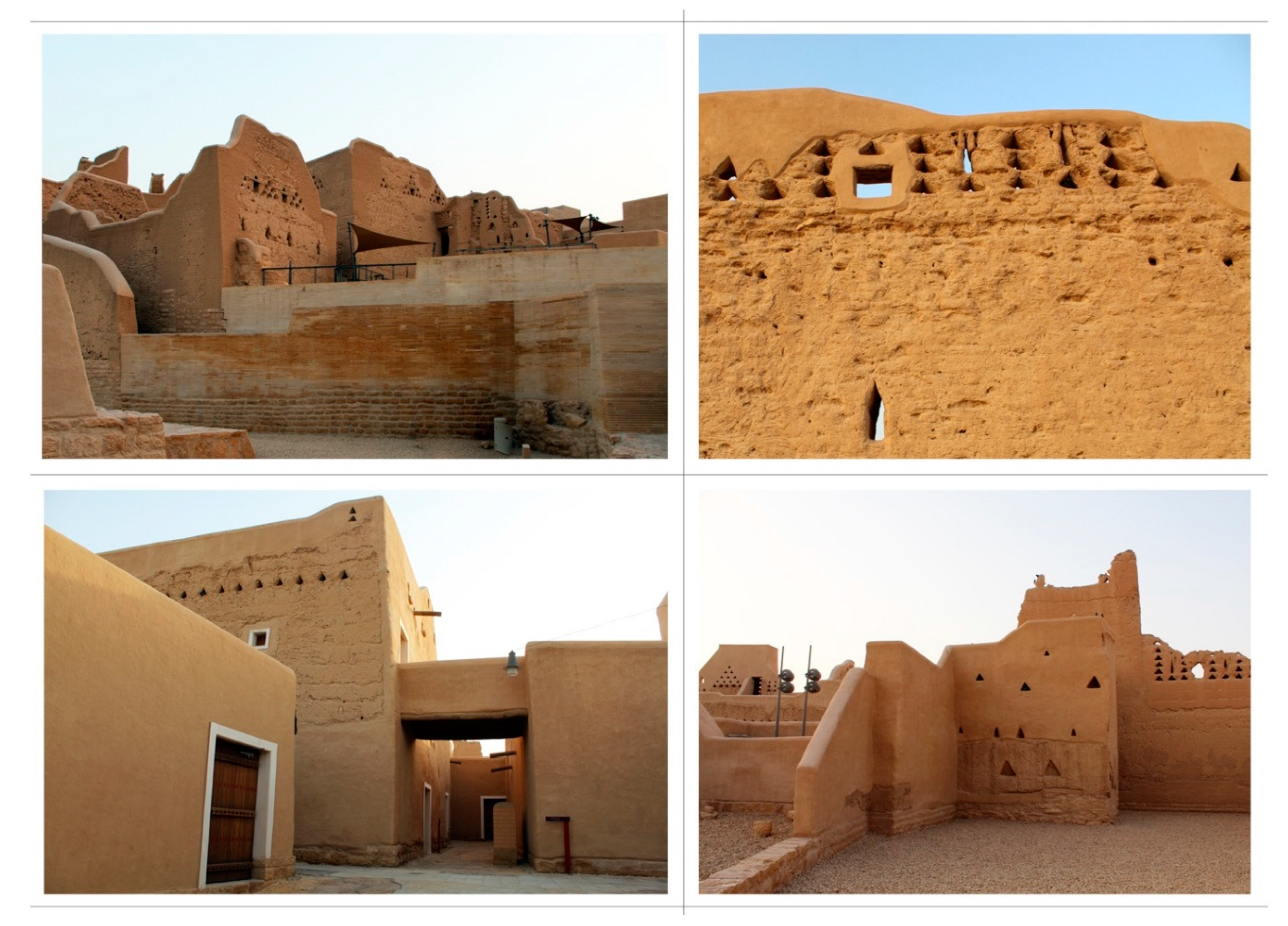

“The site of at-Turaif District in ad-Dir’iyah illustrates a significant phase in the human settlement of the central Arabian plateau, when in the mid-18th century Ad-Dir’iyah became the capital of an independent Arab State and an important religious centre. At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah is an outstanding example of traditional human settlement in a desert environment”.[67]

4.3. Heritage Conservation and Development after 2017: From Conservation Activities to Major Tourist Destination and an Exemplary Project for the Saudi Heritage Sector

“The At-Turaif District was the first historic centre with a unifying power in the Arabian Peninsula. Its influence was greatly strengthened by the teachings of Sheikh Mohammad Bin Abdul Wahhab, a great reformer of Sunni Islam who lived, preached and died in the city. After his enduring alliance with the Saudi Dynasty, in the middle of the 18th century, it is from ad-Dir’iyah that the message of Salafiyya spread throughout the Arabian Peninsula and the Muslim world”.[67]

“The citadel of at-Turaif is representative of a diversified and fortified urban ensemble within an oasis. It comprises many palaces and is an outstanding example of the Najdi architectural and decorative style characteristic of the centre of the Arabian Peninsula. It bears witness to a building method that is well adapted to its environment, to the use of adobe in major palatial complexes, along with a remarkable sense of geometrical decoration”.[67]

5. Findings and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diriyah Gate Development Authority DGDA. Work Commences on World’s Largest Cultural and Heritage Development Diriyah Gate, Starting with Bujairi District. 2020. Available online: https://dgda.gov.sa/media-center/news/news-articles/31.aspx?lang=en-uson (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Alqahtany, A.; Aravindakshan, S. Urbanization in Saudi Arabia and sustainability challenges of cities and heritage sites: Heuristical insights. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Saussure, F. Course in General Linguistics; Charles, B., Albert, S., Eds.; Harris, Roy, Open Court: La Salle, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Government. Vision 2030: National Transformation Program. 2016. Available online: http://vision2030.gov.sa/en/ntp (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Saudi Government. Quality of Life Program 2020; The Council of Economic Affairs and Development: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Adopted decisions during the 42nd session of the World Heritage Committee. In Proceedings of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage-Forty-Second Session, Manama, Bahrain, 24 June–4 July 2018; WHC/18/42.COM/18. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/168796 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- UNESCO. Item 12 of the Provisional Agenda: Revision of the Operational Guidelines. In Proceedings of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage—Extended Forty-Fourth Session, Fuzhou, China, 16–31 July 2021; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/173608 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- UNESCO. Fifteenth General Assembly of States Parties to the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, T. Beyond Eurocentrism? Heritage conservation and the politics of difference. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Yamashita, T. Methodological framework of sustainability assessment in City Sustainability Index (CSI): A concept of constraint and maximisation indicators. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.Y.; Jorge Ochoa, J.; Shah, M.N.; Zhang, X. The application of urban sustainability indicators—A comparison between various practices. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Habitat. State of the World’S Cities 2012/2013: Prosperity of Cities. Malta. 2013. Available online: www.unhabitat.org (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Nurse, K. Culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development. Small States: Economic Review and Basic Statistics 2006, 11, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The future we want: Outcome document adopted at Rio + 20 Conference on Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the Rio de Janeiro meeting, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 20–22 June 2012; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Shmelev, S.E.; Shmeleva, I.A. Sustainable cities: Problems of integrated interdisciplinary research. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 12, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijkamp, P.; Riganti, P. Assessing cultural heritage benefits for urban sustainable development. Int. J. Serv. Technol. Manag. 2008, 10, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, C.; Sutherland, M. Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appendino, F. October. Balancing heritage conservation and sustainable development—The case of Bordeaux. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 062002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogruyol, K.; Aziz, Z.; Arayici, Y. Eye of sustainable planning: A conceptual heritage-led urban regeneration planning framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Pino, J. The new holistic paradigm and the sustainability of historic cities in Spain: An approach based on the world heritage cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kou, H.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S. Conservation for sustainable development: The sustainability evaluation of the xijie historic district, dujiangyan city, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadli, F.; AlSaeed, M. A holistic overview of Qatar’s (Built) cultural heritage; towards an integrated sustainable conservation strategy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, K. “Imported Buddhism” or “Co-Creation”? Buddhist Cultural Heritage and Sustainability of Tourism at the World Heritage Site of Lumbini, Nepal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Faouri, B.F.; Sibley, M. Heritage-led urban regeneration in the context of WH listing: Lessons and opportunities for the newly inscribed city of As-Salt in Jordan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teutonico, J.M.; Matero, F. (Eds.) Managing change: Sustainable approaches to the conservation of the built environment. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual US/ICOMOS International Symposium Organized by US/ICOMOS, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 6–8 April 2001; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2003; p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovine, M. The Heritage-Scape: UNESCO, World Heritage, and Tourism; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.H.; Lin, H.-L.; Han, C.-C. Analysis of international tourist arrivals in China: The role of World Heritage sites. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cesari, C. World heritage and mosaic universalism: A view from Palestine. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2010, 10, 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskell, L. Negative heritage and past mastering in archaeology. Anthropol. Q. 2002, 75, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, M.; Butler, B. Conflict and heritage care. Anthropol. Today 2007, 23, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadi, S. UNESCO, Cultural Heritage and Outstanding Universal Value; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pozas, B.M.; Gonzalez, F.J.N. Housing Building Typology Definition in a Historical Area Based on a Case Study: The Valley, Spain; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 72, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa, J.; Deloumeaux, L.; Ellis, S. 2009 UNESCO framework for cultural statistics. Montreal. 2009. Available online: http://www.uis.unesco.org/culture/Documents/framework-cultural-statistics-culture-2009-en.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (Recommendation Text); UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Orbasli, A. Tourists in Historic Towns: Urban Conservation and Heritage Management, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichfield, N. Economics in Urban Conservation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kocabaş, A. Urban conservation in Istanbul: Evaluation and re-conceptualisation. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapp, N.L. A Methodology for the Documentation and Analysis of Urban Historic Resources; Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations, University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Larkham, P.J.; Conzen, M.P. (Eds.) Shapers of Urban form: Explorations in Morphological Agency; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Othaymeen, A. Al-Diriyah Origion and Development during the Era of the First Saudi State; Darah-King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Almogren, N. Diriyah Narrated by Its Built Environment: The Story of the First Saudi State (1744–1818). Master Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Albini, M. Traditional Architecture in Saudi Arabia: The Central Region; The Department of Antiquities and Museums-Ministry of Education: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Facey, W. Dirʻiyyah and the First Saudi State; Stacey International Publishers: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Facey, W. Back to earth-Adobe Buildings in Saudi Arabia. Rev. Middle East Stud. 1997, 33, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaqir, A. Housing Patterns Change in the City of Diriyah; Darrah Foundation: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alnaim, M.M. Searching for Urban and Architectural Core Forms in the Traditional Najdi Built Environment of the Central Region of Saudi Arabia. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Colorado at Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera Fausto, I.; Fenollosa Forner, E.J.; Serrano Lanzarote, A.B.; Perelló Roso, R. “Les Alqueries del Terme de Borriana” Anuari de l’Agrupacio Borrianenca de Cultura revista de recerca humanística i científica; Universitat Jaume I: Valencian, Spain, 2020; pp. 71–90. ISSN 1130-4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianca, S. Urban Form in the Arab World: Past and Present; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ntefeh, R.; Mannon, M.; Kasem, D. Returning to the heritage in contemporary Arab architecture in light of sustainability. Tishreen Univ. J. Res. Sci. Stud. Eng. Sci. Ser. 2014, 36, 373–394. [Google Scholar]

- Arriyadh Development Authority (ADA). The Pilot Project: A Training Program for the Implementation of the Conservation Work and Adaptive Reuse of the Domestic Dowelling in Atturaif; Arriyadh Development Authority: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arriyadh Development Authority (ADA). Diriyah Old Town Development Project Work Progress Report; Arriyadh Development Authority: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Arriyadh Development Authority (ADA). Diriyah Development Program; Arriyadh Development Authority: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ivan Cabrera-Fausto et al. Editorial Historical contexts. ANUARI d’Arquit. I Soc. Res. J. 2021, 1, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities (SCTA). At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah: Nomination Document for the Inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List”, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2009; Volume 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bartorila, M.Á.; Loredo-Cansino, R. Cultural heritage and natural component. From reassessment to regeneration. ANUARI d’Arquit. I Soc. Res. J. 2021, 1, 286–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nashwan, A. The impact of urban and agricultural development on the environment of Wadi Hanifa: Applied study on the valley in the city of Diriyah. Diriyah 2010, 13, 389–448. [Google Scholar]

- Andrés, B.; José Peinado-Cucarella, J. El estudio y puesta en valor de los refugios antiaéreos de la guerra civil española. El caso del Refugio-Museo de Cartagena. ArqueoMurcia 2008, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Fausto, I.; Fenollosa-Forner, E.; Serrano-Lanzarote, B. The new entrance to the Camí d’Onda Air-raid Shelter in the historic center of Borriana, Spain. TECHNE-J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2020, 19, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shwaish, S.; Al-Mansor, A.; Al-Dahham, F. First Fieldwork Outcomes At-Turaif District in ad-Dir’iyah; Archaeology Book Series; Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities (SCTA): Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2014; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Arriyadh Development Authority (ADA). Addiriyah: The Glorious Past and The Bright Future; Arriyadh Development Authority: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bendakir, M. At-Turaif district in ad-Dir’iyah, Saudi Arabia: The pilot project–a training program for the implementation of the conservation work and adaptive reuse of domestic dwellings in at-Turaif. In Earthen Architecture in Today’s World, Proceedings of the UNESCO International Colloquium on the Conservation of World Heritage Earthen Architecture, Paris, France, 17–18 December 2012; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. 2021. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Al-Zhrani, A. Tourism planning for historic cities the city of Dir’iya as a model. Addiriya 2010, 13, 449–480. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tokhais, A.; Thapa, B. Management issues and challenges of UNESCO world heritage sites in Saudi Arabia. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljahani, T. Visitor Center Design and Possibilities for Visitor Engagement at Ad-Dir’iyah Heritage Site. Master Thesis, The Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah. 2022. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1329/ (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Royal Commission for Riyadh City Authority (RCRC). Hanifah Valley Urban Code; Royal Commission for Riyadh City Authority: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arriyadh Development Authority (ADA). Al-Bujairy: Heart of the Call; Arriyadh Development Authority; Medina Publishing: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aliraqi, A. Heritage-based Entertainment: Empirical Evidence from Diriyah, Saudi Arabia. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 18, 467–480. [Google Scholar]

- Lochhead, G. Jerry Inzerillo, CEO, Diriyah Gate Development Authority. Hospitality Interiors. 2021. Available online: https://www.hospitality-interiors.net/interviews/articles/2021/06/1866688471-jerry-inzerillo-ceo-diriyah-gate-development-authority (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Arriyadh Development Authority (ADA). Salmaniah Architecture Guidelines; Arriyadh Development Authority: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Architecture and Design Commission. King Salman Charter for Architecture and Urbanism; Architecture and Design Commission: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Michele Caja. Reconstructing historical context. German cities and the case of Lübeck. ANUARI d’Arquit. I Soc. Res. J. 2021, 1, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, K.; Martinez-Molina, A.; Dupont, W. In Situ Assessment of HVAC System Impact in Façades of a UNESCO World Heritage Religious Building. ANUARI d’Arquit. I Soc. Res. J. 2021, 1, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diriyah Gate Development Authority DGDA. Samhan Heritage Plots: Design Brief; Diriyah Gate Development Authority: Diriyah, Saudi Arabia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Diriyah Gate Development Authority DGDA. Diriyah Gate Jewel of the Kingdom; Development Control Regulations; Diriyah Gate Development Authority & ATKINS: Diriyah, Saudi Arabia, 2020; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

| Aspects of Analysis | Heritage Conservation and Development before 2010 | Heritage Conservation and Development after 2010 until 2017 | Heritage Conservation and Development after 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical |

|

|

|

| Social |

|

|

|

| Economic |

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bay, M.A.; Alnaim, M.M.; Albaqawy, G.A.; Noaime, E. The Heritage Jewel of Saudi Arabia: A Descriptive Analysis of the Heritage Management and Development Activities in the At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah, a World Heritage Site (WHS). Sustainability 2022, 14, 10718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710718

Bay MA, Alnaim MM, Albaqawy GA, Noaime E. The Heritage Jewel of Saudi Arabia: A Descriptive Analysis of the Heritage Management and Development Activities in the At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah, a World Heritage Site (WHS). Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710718

Chicago/Turabian StyleBay, Mohammed Abdulfattah, Mohammed Mashary Alnaim, Ghazy Abdullah Albaqawy, and Emad Noaime. 2022. "The Heritage Jewel of Saudi Arabia: A Descriptive Analysis of the Heritage Management and Development Activities in the At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah, a World Heritage Site (WHS)" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710718