Calibrating Evolution of Transformative Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the general characteristics of studies related to TT?

- (2)

- What is the actual quantitative and objective state of knowledge regarding TT?

- (3)

- How has the research interest evolved?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism and Transformation

2.2. Transformative Tourism Experience

2.3. Ethos

2.4. Setting

2.4.1. Time

2.4.2. Destination

2.5. Catalysers

2.5.1. Risk, Challenge and Novelty

2.5.2. Authenticity and Liminality

2.5.3. Social Dynamics and Communitas

2.5.4. Emotions and Peak Experiences

2.5.5. Self-Reflection

2.6. Tourists’ Outcomes

2.6.1. Psychological

2.6.2. Physical

2.6.3. Social

2.6.4. Learning and Mastery

2.7. Role of Facilitators

Facilitators’ Outcomes

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Article Screening

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. General Literature Trends of Transformative Tourism Related Publications

4.2. Geographic Distribution

4.3. Citation Analysis

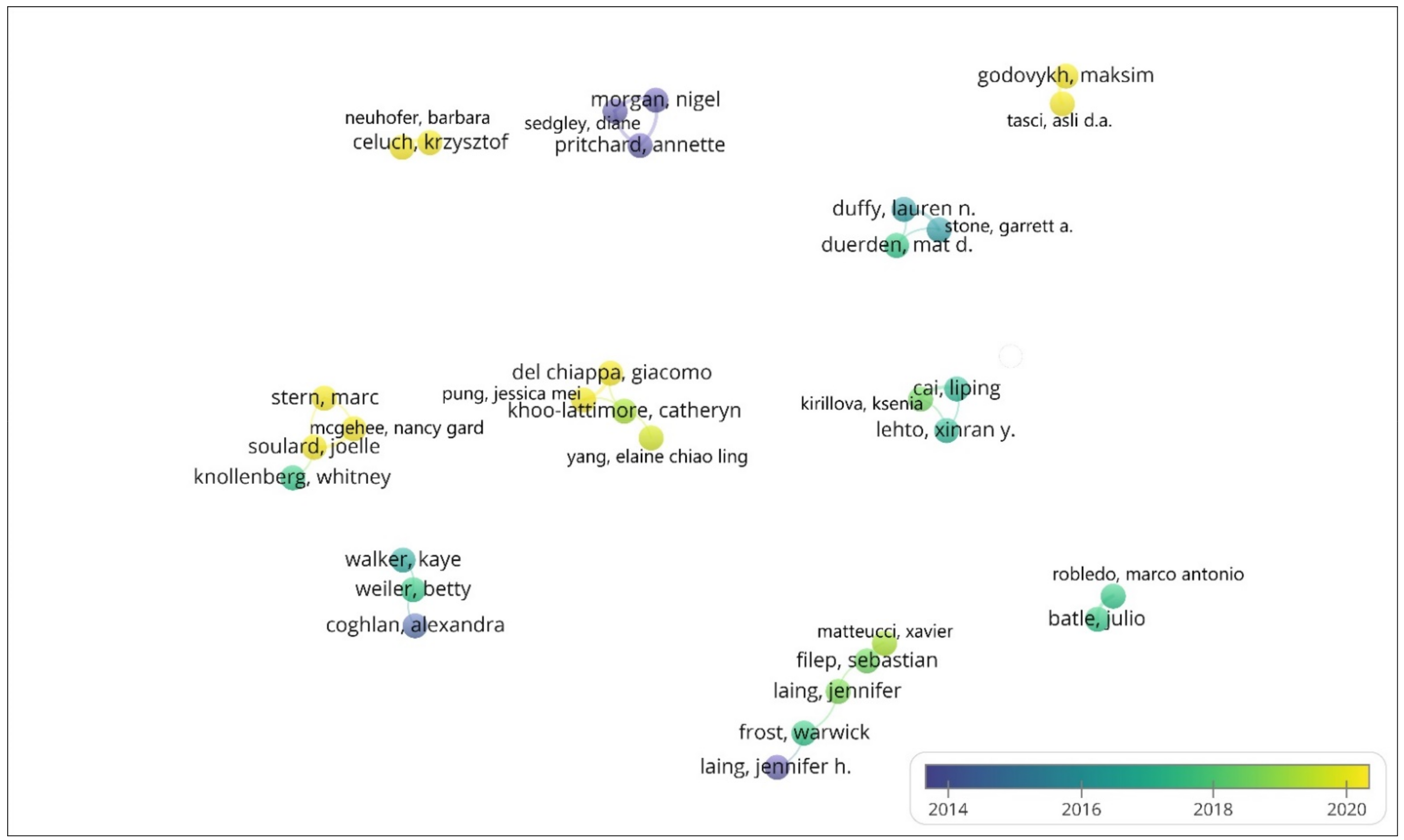

4.4. Co-Authorship

4.5. Journal and Publisher Analysis

4.6. Universities and Funding Associations

4.7. Intellectual Structure and Emerging Trends

4.8. Theme Identifiers Analysis

5. Conclusions and Directions for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lean, G.L. Transformative travel: A mobilities perspective. Tour. Stud. 2012, 12, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.D. Journeys into transformation: Travel to an “other” place as a vehicle for transformative learning. J. Transform. Educ. 2010, 8, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Seo, S. A critical review of research on customer experience management: Theoretical, methodological and cultural perspectives. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2218–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, E.M. Transformation of self in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y. Transformational Tourism: Tourist Perspectives; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2013; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Tasci, A.D.; Godovykh, M. An empirical modeling of transformation process through trip experiences. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.L. Transformative travel: An enjoyable way to foster radical change. ReVision A J. Conscious. Transform. 2010, 32, 54–61. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270916763_Transformative_Travel_An_Enjoyable_Way_to_Foster_Radical_Change (accessed on 11 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Pung, J.M.; Gnoth, J.; Del Chiappa, G. Tourist transformation: Towards a conceptual model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 81, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, M.A.; Batle, J. Transformational tourism as a hero’s journey. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1736–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.; Weiler, B. Examining transformative processes in volunteer tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning, 1st ed.; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kottler, J.A. Transformative travel. Futurist 1998, 32, 24–28. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/218560225/fulltextPDF/6B58F2C624DE4184PQ/1?accountid=136549 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Arnould, E.J.; Price, L.L.; Otnes, C. Making magic consumption: A study of white-water river rafting. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 1999, 28, 33–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, C. This trip really changed me: Backpackers’ narratives of self-change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, T.S. Performing backpacking: Constructing “authenticity” every step of the way. Text Perform. Q. 2004, 24, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L. The transformative power of the international sojourn: An ethnographic study of the international student experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, I. Ways of looking: Observation and transformation at the Holocaust Memorial, Berlin. Mem. Stud. 2009, 2, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allman, T.L.; Mittelstaedt, R.D.; Martin, B.; Goldenberg, M. Exploring the motivations of base jumpers: Extreme sport enthusiasts. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliford, M. Touring “country”, sharing “home”: Aboriginal tourism, Australian tourists and the possibilities for cultural transversality. Tour. Stud. 2010, 10, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J. Autonomous cross-cultural hardship travel (ACHT) as a medium for growth, learning, and a deepened sense of self. World Futures 2010, 66, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y. Connection between Travel, Tourism and Transformation. In Transformational Tourism: Tourist Perspectives; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2013; pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pung, J.M.; Del Chiappa, G. An exploratory and qualitative study on the meaning of transformative tourism and its facilitators and inhibitors. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 24, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ourahmoune, N. Narrativity, temporality, and consumer-identity transformation through tourism. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, C.; Brown, G.; Howat, G. Wellness tourists: In search of transformation. Tour. Rev. 2011, 66, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y. Transformational Tourism: Host Perspectives; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, V.; Walter, P. Community-based ecotourism and the transformative learning of homestay hosts in Cambodia. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D. Transformative experiences via Airbnb: Is it the guests or the host communities that will be transformed? J. Tour. Futures 2019, 5, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulard, J.; McGehee, N.G.; Stern, M. Transformative tourism organizations and glocalization. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallan, S.A.; Kabadayi, S.; Ali, F.; Helkkula, A.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y. Transformative hospitality services: A conceptualization and development of organizational dimensions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L. Tourism: A catalyst for existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, M.L. South African township residents describe the liminal potentialities of tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Tanyatanaboon, M.; Lehto, X.Y. Conceptualizing transformative guest experience at retreat centers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 49, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, S.; Brown, L. Travelling with a purpose: An ethnographic study of the eudemonic experiences of volunteer expedition participants. Tour. Stud. 2018, 19, 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decrop, A.; Del Chiappa, G.; Mallarge, J.; Zidda, P. Couchsurfing has made me a better person and the world a better place: The transformative power of collaborative tourism experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.W. Building Upon the Theoretical Debate: A Critical Review of the Empirical Studies of Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory. Adult Educ. Q. 1997, 48, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, D.; Kent, A.J. Transformative landscapes: Liminality and visitors’ emotional experiences at German memorial sites. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 250–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykoudi, D.M.; Zouni, G.; Tsogas, M.M. Self-love emotion as a novel type of love for tourism destinations. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 24, 390–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Manyamba, V.N. Towards an emotion-focused, discomfort-embracing transformative tourism education. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 26, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.J. Designing tourism experiences for inner transformation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B.; Celuch, K.; To, T.L. Experience design and the dimensions of transformative festival experiences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2881–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B.; Egger, R.; Yu, J.; Celuch, K. Designing experiences in the age of human transformation: An analysis of Burning Man. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 91, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortezza, F.; Figueiredo, B.; Scaraboto, D.; Del Chiappa, G. Managing multiple logics to facilitate consumer transformation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulard, J.; McGehee, N.; Knollenberg, W. Developing and Testing the Transformative Travel Experience Scale (TTES). J. Travel Res. 2020, 60, 923–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.; Ferreira, A.; Costa, C.; Santos, J.A.C. A Model for the Development of Innovative Tourism Products: From Service to Transformation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirakranont, R.; Sakdiyakorn, M. Conceptualizing meaningful tourism experiences: Case study of a small craft beer brewery in Thailand. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seočanac, M. Transformative experiences in nature-based tourism as a chance for improving sustainability of tourism destination. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 6, 1–10. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360054620_Transformative_experiences_in_nature-based_tourism_as_a_chance_for_improving_sustainability_of_tourism_destination (accessed on 23 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.A.; Duffy, L.N. Transformative Learning Theory: A Systematic Review of Travel and Tourism Scholarship. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2015, 15, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, I.D.; Ainsworth, G.B.; Crowley, J. Transformative travel as a sustainable market niche for protected areas: A new development, marketing and conservation model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1650–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, M.W.; Wang, Y.; Kwek, A. Conceptualising co-created transformative tourism experiences: A systematic narrative review. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 1997, 1997, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundbo, J.; Serensen, F. Handbook on the Experience Economy; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, Australia, 2013; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, J.B.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre. Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Folmer, A.; Tengxiage, A.T.; Kadjik, H.; Wright, A.J. Exploring Chinese millennials’ experiential and transformative travel: A case study of mountain bikers in Tibet. J. Tour. Futures 2019, 5, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Determining the factors affecting the memorable nature of travel experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahakoon, T.; Pike, S.; Beatson, A. Transformative destination attractiveness: An exploration of salient attributes, consequences, and personal values. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 845–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. Tourism and Existential Transformation: An Empirical Investigation. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, R.; Chowdhary, N.; Ranjan, A. Spiritual tourism for psychotherapeutic healing post COVID-19. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, N.; Insch, A. Enabling transformative experiences through nature-based tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Weiler, B. A new model for guide training and transformative outcomes: A case study in sustainable marine wildlife ecotourism. J. Ecotourism 2017, 16, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorashid, N.; Chin, W.L. Coping with COVID-19: The Resilience and Transformation of Community-Based Tourism in Brunei Darussalam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomazos, K.; Butler, R. The volunteer tourist as “Hero”. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggioli, A. Transformative Experience Design. Human Computer Confluence: Transforming Human Experience Through Symbiotic Technologies; De Gruyter: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, S.; Lloyd, K.; Suchet-Pearson, S.; Burarrwanga, L.; Ganambarr, R.; Ganambarr, M.; Ganambarr, B.; Maymuru, D.; Tofa, M. Meaningful tourist transformations with Country at Bawaka, North East Arnhem Land, northern Australia. Tour. Stud. 2017, 17, 443–467. [Google Scholar]

- Duerden, M.D.; Lundberg, N.R.; Ward, P.; Taniguchi, S.T.; Hill, B.; Widmer, M.A.; Zabriskie, R. From ordinary to extraordinary: A framework of experience types. J. Leis. Res. 2018, 49, 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. How critical reflection triggers transformative learning. In Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 3rd ed.; New World Library: Novato, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Roberson, D.N., Jr. Modern Day Explorers—The Way to a Wider World. World Leis. J. 2002, 44, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzik, A.; Pritchard, A.; Morgan, N.; Sedgley, D. The potential of arts-based transformative research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulard, J.; McGehee, N.G.; Stern, M.J.; Lamoureux, K.M. Transformative tourism: Tourists’ drawings, symbols, and narratives of change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Transformative perspectives of tourism: Dialogical perceptiveness. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grof, S. Implications of modern consciousness research for psychology: Holotropic experiences and their healing and heuristic potential. Humanist. Psychol. 2003, 31, 50–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y. Transformational Tourism: Tourist Perspectives; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2013; p. XII. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. Sociology 1979, 13, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. What triggers transformative tourism experiences? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2017, 42, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, S. Transnational migrant home visits as identity practice: The case of African migrants in South Africa. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 63, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Kirillova, K. The formative nature of graduation travel. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2021, 2, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, G.B.; McIntosh, A.J.; Zahra, A.L. Tourism and spirituality: A phenomenological analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzrokh, M.; Muldoon, M.; Torabian, P.; Mair, H. The memory-work sessions: Exploring critical pedagogy in tourism. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 21, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.A.; Levy, S.J. The Temporal and Focal Dynamics of Volitional Reconsumption: A Phenomenological Investigation of Repeated Hedonic Experiences. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottola, P. Somewhat empty meeting grounds: Travelers in South India. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 44, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Yang, X. I’m here for recovery: The eudaimonic wellness experiences at the Le Monastere des Augustines Wellness hotel. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 802–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živoder, S.B.; Ateljević, I.; Čorak, S. Conscious travel and critical social theory meets destination marketing and management studies: Lessons learned from Croatia. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, X. Online expression as Well-be(com)ing: A study of travel blogs on Nepal by Chinese female tourists. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pung, J.M.; Yung, R.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Del Chiappa, G. Transformative travel experiences and gender: A double duoethnography approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 538–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavitz, K.J.; Butz, D. Not That Alternative: Short-term Volunteer Tourism at an Organic Farming Project in Costa Rica. ACME 2011, 10, 412–441. Available online: https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/905/761 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Bone, J.; Bone, K. Voluntourism as cartography of self: A Deleuzian analysis of a postgraduate visit to India. Tour. Stud. 2018, 18, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueddefeld, J.; Duerden, M.D. The transformative tourism learning model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 94, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radel, K.; Hillman, W. Not ‘On Vacation’: Survival Escapist Travel as an Agent of Transformation. In Transformational Tourism: Tourist Perspectives; Reisinger, Y., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2013; pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P.; van Nieuwerburgh, C. The lived experience of long-term overland travel. Ann. Tour. Res. Empirical Insights 2022, 3, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.; Price, L.L. River magic: Extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillette, A.K.; Douglas, A.C.; Andrzejewski, C. Yoga tourism—A catalyst for transformation? Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 22, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, W.C.; Stern, M.; Blahna, D.; Stein, T. Recreation as a transformative experience: Synthesizing the literature on outdoor recreation and recreation ecosystem services into a systems framework. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 38, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, P.; Medway, D. Ecosophy and tourism: Rethinking a mountain resort. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, R.G. Catalysts for transformative learning in community-based ecotourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1356–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.; Jepson, N. Critical transformations and global development: Materials for a new analytical framework. Area Dev. Policy 2018, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J. Transformational Tourism, Nature and Wellbeing: New Perspectives on Fitness and the Body. Sociol. Ruralis 2012, 52, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C.; Choi, Y.; Wang, A.Y. Tourism Representations of Chinese Cosmology: The Case of Feng Shui Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 975–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Paek, S.; Kim, T.T.; Lee, T.H. Health tourism Needs for healing experience and intentions for transformation in wellness resorts in Korea. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 2015, 27, 1881–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; McIntosh, A. Motivations, experiences and perceived impacts of visitation at a Catholic monastery in New Zealand. J. Herit. Tour. 2014, 9, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowen, I. The transformational festival as a subversive toolbox for a transformed tourism: Lessons from Burning Man for a COVID-19 world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. Transformative experiences in political life. J. Polit. Philos. 2017, 25, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterchele, D. Memorable tourism experiences and their consequences: An interaction ritual (IR) theory approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 81, 102847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Moscardo, G. Moving beyond sense of place to care of place: The role of Indigenous values and interpretation in promoting transformative change in tourists’ place images and personal values. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1243–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Arcodia, C. Power and empowerment: How Asian solo female travellers perceive and negotiate risks. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, J.H.; Crouch, G.I. Lone wolves? Isolation and solitude within the frontier travel experience. Geogr. Ann. A Phys. Geogr. 2009, 91, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.B.; Brownlee, M.T.J.; Kellert, S.R.; Ham, S.H. From awe to satisfaction: Immediate affective responses to the Antarctic tourism experience. Polar Rec. 2012, 48, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosangit, C.; Hibbert, S.; McCabe, S. “If I was going to die I should at least be having fun”: Travel blogs, meaning and tourist experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 55, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, W.J.L.; Liu, X.N.; Filep, C.V. Transformative potential of events—The case of gay ski week in Queenstown, New Zealand. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danby, P.; Grajfoner, D. Human–Equine Tourism and Nature-Based Solutions: Exploring Psychological Well-Being Through Transformational Experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 607–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D.; Đurađević, M.; Senić, V.; Kostić, M. A joyful river ride: A transformative event experience. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 39, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.B.; Lo, A.; Wu, J. Pleasure or pain or both? Exploring working holiday experiences through the lens of transformative learning theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrizos, S.; Kostopoulos, I.; Powers, L. Volunteer Tourism as a Transformative Experience: A Mixed Methods Empirical Study. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 878–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidon, E.S.; Rickly, J.M. Alienation and anxiety in tourism motivation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 69, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. Existential Authenticity and Anxiety as Outcomes: The Tourist in the Experience Economy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Rickly, J. ‘The smell of death and the smell of life’: Authenticity, anxiety and perceptions of death at Varanasi’s cremation grounds. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.K. The enchanted snake and the forbidden fruit: The ayahuasca ‘fairy tale’ tourist. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 818–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Hunter-Jones, P.; McCabe, S. Emotions in tourist experiences: Advancing our conceptual, methodological and empirical understanding. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogeorgopoulos, N. Finding oneself while discovering others: An existential perspective on volunteer tourism in Thailand. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 65, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Wood, E.H.; Senaux, B.; Dai, G. Liminality and festivals—Insights from the East. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80, 102810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, X. Sustaining Faculty Development through Visiting Scholar Programmes: A Transformative Learning Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, E. Experiential responsible consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela-Huotari, K.; Patrício, L.; Zhang, J.; Karpen, I.O.; Sangiorgi, D.; Anderson, L.; Bogicevic, V. Service system transformation through service design: Linking analytical dimensions and service design approaches. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, I.D.; Stricker, H.K.; Hagenloh, G. Outcome-focused national park experience management: Transforming participants, promoting social well-being, and fostering place attachment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 358–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D. Rural Food and Wine Tourism in Canada’s South Okanagan Valley: Transformations for Food Sovereignty? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, H.M. Global-Service Learning and Student-Athletes: A Model for Enhanced Academic Inclusion at the University of Washington. Ann. Glob. Health 2017, 82, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.L. Intentional Community: An Anthropological Perspective; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmi, E.; Sacco, L.P.; Crociata, A.; Agovino, M. The Lucca Comics and Games Festival as a platform for transformational cultural tourism: Evidence from the perceptions of residents. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 27, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Tasci, A.D.A. Customer experience in tourism: A review of definitions, components, and measurements. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Jia, W. The influence of eliciting awe on pro-environmental behavior of tourist in religious tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassler, P.; Kuteynikova, M. Living travel vulnerability: A phenomenological study. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A. The humanistic psychology–positive psychology divide: Contrasts in philosophical foundations. Am. Psychol. 2013, 68, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Cognition of being in the peak experiences. J. Genet. Psychol. 1959, 94, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, X. Existential hapax as tourist embodied transformation. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda, C.; Belknap, R. Short of transformation: American ADN students’ thoughts, feelings, and experiences of studying abroad in a low-income country. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2012, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, H.; Okoe, A.F.; Hinson, R.E. Dark tourism: Exploring tourist’s experience at the Cape Coast Castle, Ghana. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 27, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, C.I.; Montgomery, C.; Araújo, H.C. ‘You went to Europe and returned different’: Transformative learning experiences of international students in Portugal. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 17, 696–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukoff, M.M. Immersion in Indigenous Agriculture and Transformational Learning. Anthropol. Humanism 2018, 43, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamashiro, R. Planetary Consciousness, Witnessing the Inhuman, and Transformative Learning: Insights from Peace Pilgrimage Oral Histories and Autoethnographies. Religions 2018, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manniche, J.; Larsen, K.T.; Broegaard, R.B. The circular economy in tourism: Transition perspectives for business and research. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 21, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiou, E. The Importance of Ritual Discourse in Framing Ayahuasca Experiences in the Context of Shamanic Tourism. Anthropol. Conscious. 2020, 31, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M. The reflexive tourist. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, A. Energy and transformation in alternative pilgrimages to Catholic shrines: Deconstructing the tourist/pilgrim divide. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2014, 12, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Pan, B.; Ahn, J.B. Family trip and academic achievement in early childhood. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80, 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawa, J. Spiritual tourism as a quest. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Perspective transformation. Adult Educ. Q. 1978, 28, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, S.; Wearing, S.; Lyons, K.; Tarrant, M.; Landon, A. A rite of passage? Exploring youth transformation and global citizenry in the study abroad experience. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2017, 42, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, J.H.; Frost, W. Journeys of well-being: Women’s travel narratives of transformation and self-discovery in Italy. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, C. Performing Identity: Touristic Narratives of Self-Change. Text Perform. Q. 2004, 24, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volo, S. Eudaimonic well-being of islanders: Does tourism contribute? The case of the Aeolian Archipelago. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, S. Watching narratives of travel-as-transformation in The Beach and The Motorcycle Diaries. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2014, 12, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, R.G.; Casotti, L.M. Travels and Transformation of the Existential Condition: Narratives and Representations in Films Starring the Elderly. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Tur. 2020, 14, 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Unpacking visitors’ experiences at dark tourism sites of natural disasters. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, K.G.; Hornby, S.M. Celebrating is remembering: OUTing the Past as a study in the reflective and transformative potential of small events. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events, 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneller, A.J.; Coburn, S. For-profit environmental voluntourism in Costa Rica: Teen volunteer, host community, and environmental outcomes. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 832–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikjoo, A.; Markwell, K.; Nikbin, M.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. The flag-bearers of change in a patriarchal Muslim society: Narratives of Iranian solo female travelers on Instagram. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWha, M.; Frost, W.; Laing, J. Travel writers and the nature of self: Essentialism, transformation and (online) construction. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Creating a balanced family travel experience: A perspective from the motivation-activities-transformative learning chain. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 41, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, S.; Deery, M. Towards a Picture of Tourists’ Happiness. J. Tour. Anal. 2010, 15, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiby, M.A.; Duedahl, E.; Øian, H.; Ericsson, B. Exploring sustainable experiences in tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 20, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathijsen, A. Home, sweet home? Understanding diasporic medical tourism behaviour. Exploratory research of polish immigrants in Belgium. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J. Nature, wellbeing and the transformational self. Geogr. J. 2014, 181, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.C. From drifter to gap year tourist: Mainstreaming backpacker travel. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 998–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brymer, E.; Schweitzer, R.D. Evoking the ineffable: The phenomenology of extreme sports. Psychol. Conscious Theory Res. Pract. 2017, 4, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C. The transformative potential of community-created consent culture. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2020, 12, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E. Tour-guiding as a pious place-making practice: The case of the Sehitlik Mosque, Berlin. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.B. Becoming ‘enchanted’ in agro-food spaces: Engaging relational frameworks and photo elicitation with farm tour experiences. Gend. Place Cult. 2018, 25, 1646–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, P.; Peters, A.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The (im)possibilities of doing tourism otherwise: The case of settler colonial Australia and the closure of the climb at Uluru. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litzelman, D.K.; Gardner, A.; Einterz, R.M.; Owiti, P.; Wambui, C.; Huskins, J.C.; Schmitt-Wendholt, K.M.; Stone, G.S.; Ayuo, P.O.; Inui, T.S.; et al. On Becoming a Global Citizen: Transformative Learning Through Global Health Experiences. Ann. Glob. Health 2017, 83, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, H.L.; Gibson, H.J.; Tarrant, M.A.; Perry, L.G.; Stoner, L. Transformational learning through study abroad: US students’ reflections on learning about sustainability in the South Pacific. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inversini, A.; Rega, I.; Gan, S.W. The transformative learning nature of malaysian homestay experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakio, K.; Mattelmäki, T. Future Skills of Design for Sustainability: An Awareness-Based Co-Creation Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P.G.; Reimer, J.K. The “ecotourism curriculum” and visitor learning in community-based ecotourism: Case studies from Thailand and Cambodia. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, G.T.; Dredge, D. Collaborative tourism-making: An interdisciplinary review of co-creation and a future research agenda. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeone, A.; Sebastiani, R. Transformative Service Research in Hospitality. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, R.; Gilmore, A. Heritage site management: From dark tourism to transformative service experience? Serv. Ind. J. 2015, 35, 898–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, H.; Mackenzie, S.H.; Filep, S. Facilitating self-development: How tour guides broker spiritual tourist experiences. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormond, M.; Vietti, F. Beyond multicultural ‘tolerance’: Guided tours and guidebooks as transformative tools for civic learning. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender, R.C.; Swanson, J.R.; Wright, K. Transformative travel: Transformative learning through education abroad in a niche tourism destination. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 27, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. New technologies in tourism: From multi-disciplinary to anti-disciplinary advances and trajectories. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundner, L.; Neuhofer, B. The bright and dark sides of artificial intelligence: A futures perspective on tourist destination experiences. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, K. Childhood studies and orphanage tourism in Cambodia. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 55, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, J.; Couto, G.; Sousa, A.; Pimentel, P.; Oliveira, A. Idealizing adventure tourism experiences: Tourists’ self-assessment and expectations. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, J.; Day, J.; Crerar, A. Uncertainty, story-telling and transformative learning: An instructor’s experience of TEFI’s Walking Workshop in Nepal. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2019, 19, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, S. Working towards sincere encounters in volunteer tourism: An ethnographic examination of key management issues at a Nordic eco-village. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1617–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.K.A.; Ma, J.; Xiong, X. Touristic experience at a nomadic sporting event: Craving cultural connection, sacredness, authenticity, and nostalgia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, M.F.; Mason, P.A. Transformative Tour Guiding: Training Tour Guides to be Critically Reflective Practitioners. J. Ecotourism 2003, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.A.; Duerden, M.D.; Duffy, L.N.; Hill, B.J.; Witesman, E.M. Measurement of transformative learning in study abroad: An application of the learning activities survey. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 21, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinčić, D.A.; Matečić, I. Broken but Well: Healing Dimensions of Cultural Tourism Experiences. Sustainability 2021, 13, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Rodríguez, A.; Ruíz-Navarro, J. Changes in the intellectual structure of strategic management research: A bibliometric study of the Strategic Management Journal, 1980–2000. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 981–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.C. Publish and perish? Bibliometric analysis, journal ranking and the assessment of research quality in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lyu, J. Inspiring awe through tourism and its consequence. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 77, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.; Vada, S.; Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo, C.; Le, T.H. Recreating history: The evolving negotiation of staged authenticity in tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Regt, A.; Plangger, K.; Barnes, S.J. Transforming experiences from story-telling to story-doing. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimiás, A.; Mitev, A.; Michalkó, G. Narrative transportation and travel: The mediating role of escapism and immersion. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sie, L.; Pegg, S.; Phelan, K.V. Senior tourists’ self-determined motivations, tour preferences, memorable experiences and subjective well-being: An integrative hierarchical model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.H. How can we know what we think until we see what we said? A citation and citation context analysis of Karl Wieck’s, ‘The Social Psychology of Organizing’. Organ. Stud. 2006, 27, 1675–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegard, O.; Wallin, J.A. The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: How great is the impact? Scientometrics 2015, 105, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echchakoui, S.; Barka, N. Industry 4.0 and its impact in plastics industry: A literature review. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2020, 20, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tague-Sutcliffe, J. An introduction to infometrics. Inf. Process. Manag. 1992, 28, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvani, A.; Lew, A.A.; Perez, M.S. COVID-19 is expanding global consciousness and the sustainability of travel and tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.J.; Petrick, J.F. The Educational Benefits of Travel Experiences: A Literature Review. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. Asymmetrical Dialectics of Sustainable Tourism: Toward Enlightened Mass Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.; Gooch, M. Applying a transformative learning framework to volunteer tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acedo, F.J.; Barroso, C.; Casanueva, C.; Galan, J.L. Co-authorship in management and organizational studies: An Empirical and Network Analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 957–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgley, D.; Pritchard, A.; Morgan, N. Tourism and ageing: A transformative research agenda. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnaert, L. Social tourism participation: The role of tourism inexperience and uncertainty. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, D.; Iñesta, A.; Castelló, M. Tourism for all. Educating to foster accessible accommodation. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2022, 30, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; McCabe, S. The role of liminality in residential activity camps. Tour. Stud. 2015, 15, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, S.M.A.; Hosany, S.; O’Brien, J. Storytelling in destination brands’ promotional videos. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veréb, V.; Azevedo, A. A quasi-experiment to map innovation perception and pinpoint innovation opportunities along the tourism experience journey. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 41, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liutikas, D. The manifestation of values and identity in travelling: The social engagement of pilgrimage. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, S.L.; Ivanovic, M. Building the Case for Transformative Tourism in South Africa. African J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 717–731. Available online: https://www.ajhtl.com/uploads/7/1/6/3/7163688/article_22_9_4__717-731.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Collinson, E.; Baxter, I. Liminality and contemporary engagement: Knockando Wool Mill—A cultural heritage case study. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, S.L.; Ivanovic, M. The revealing case of Cultural Creatives as transmodern tourists in Soweto, South Africa. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2019, 26, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, P.; Doohan, K. It’s not about believing’: Exploring the transformative potential of cultural acknowledgement in an Indigenous tourism context. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2013, 54, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer-Escalante, J.P. Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War, and the politics of guerrilla travel writing. Stud. Travel Writ. 2011, 15, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.L.; Hur, J.Y.C.; Hoffman, J. Temple Stay-cation: Opportunities During and Beyond Pandemic Conditions. J. Tour. Sport Manag. 2021, 4, 357–364. Available online: https://www.scitcentral.com/documents/b716dd54880dc9ea85fabda7f35639b0.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2022).

- Vidickienė, D.; Vilkė, R.; Gedminaitė-Raudonė, Z. Transformative tourism as an innovative tool for rural development. Eur. Countrys. 2020, 12, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu-Prévost, D.; Cormier, M.; Heller, S.M.; Nelson-Gal, D.; McRae, K. Welcome to Wonderland? A Popular Study of Intimate Experiences and Safe Sex at a Transformational Mass Gathering (Burning Man). Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 2055–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, A. Asian solo male travelling mobilities—An autoethnography. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 14, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.M.; Palrão, T.; Rodrigues, R.I. Creativity as an opportunity to stimulate a cognitive approach to tourist demand. Front Psychol. 2021, 12, 711930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, X.; Filep, S. Eudaimonic tourist experience: The case of flamenco. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertella, G.; Vidmar, B. Learning to face global food challenges through tourism experiences. J. Tour. Futures 2019, 5, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor, L.; Mayseless, O. How Personal Transformation Occurs Following a Single Peak Experience in Nature: A Phenomenological Account. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2020, 60, 865–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Sha, J.; Scott, N. Restoration of Visitors through Nature-Based Tourism: A Systematic Review, Conceptual Framework, and Future Research Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielenga, B. New experiences in nature areas: Architecture as a tool to stimulate transformative experiences among visitors in nature areas? J. Tour. Futures, 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Force, A.; Manuel-Navarrete, D.; Benessaiah, K. Tourism and transitions toward sustainability: Developing tourists’ pro-sustainability agency. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchner, S.; Schelhas, Z.; Brosius, P.J.; Nibbelink, N.P. Zen and the Art of the Selfie Stick: Blogging the John Muir Trail Thru-Hiking Experience. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, F.; Østergaard, P. Extraordinary consumer experiences: Why immersion and transformation cause trouble. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 14, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidickienė, D.; Gedminaitė-Raudonė, Z.; Vilkė, R.; Chmielinski, P.; Zobena, A. Barriers to start and develop transformative ecotourism business. Eur. Countrys. 2021, 13, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjuraman, V.; Hussin, R. Social Transformations of Rural Communities Through Ecotourism: A Systematic Review. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2017, 9, 54–66. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20183073520 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Lackey, Q.N.; Pennisi, L. Ecotour guide training program methods and characteristics: A case study from the African bush. J. Ecotourism 2020, 19, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeler, S.; Lück, M.; Schänzel, H. Paradoxes and actualities of off-the-beaten-track tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aall, C. Sustainable Tourism in Practice: Promoting or Perverting the Quest for a Sustainable Development? Sustainability 2014, 6, 2562–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, Y.; Yan, L. “Who is Buddha? I am Buddha.”—The motivations and experiences of Chinese young adults attending a Zen meditation camp in Taiwan. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2020, 21, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B. Emotional Connection, Materialism, and Religiosity: An Islamic Tourism Experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 1011–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; White, G.R.T.; Samuel, A. To pray and to play: Post-postmodern pilgrimage at Lourdes. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husemann, K.C.; Eckhardt, G.M.; Grohs, R.; Saceanu, R.E. The dynamic interplay between structure, anastructure and antistructure in extraordinary experiences. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3361–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, T.M.; da Rosa, A.P. Faith, entertainment, and conflicts on the Camino de Santiago (The Way of St. James): A case study on the mediatization of the pilgrimage experience on Facebook groups. Essachess 2017, 10, 145–169. Available online: https://doaj.org/article/8c0374daaf7a49258c9c9615bdbe5b25 (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Serrallonga, S.A. Pilgrim’s Motivations: A Theoretical Approach to Pilgrimage as a Peacebuilding Tool. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2020, 8, 58–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Labajo, V.; Ramos, I.; del Valle-Brena, A.G. A Guest at Home: The experience of Chinese Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, H.A.; Baker, S.B.; Foxx, S.B.P. The therapeutic value of pilgrimage: A grounded theory study. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2014, 17, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumer, S. The Camino de Santiago in Late Modernity: Examining Transformative Aftereffects of the Pilgrimage Experience. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2021, 9, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ajarma, K. After Haji: Muslim Pilgrims Refashioning Themselves. Religions 2021, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowson, R. Biker Revs’ on Pilgrimage: Motorbiking Vicars Visiting Sacred Sites. Religions 2021, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Mura, P.; Hall, M.; Fontaine, J. Drug or spirituality seekers? Consuming ayahuasca. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.; González, R.C.L.; Fernández, B.M.C. Spiritual tourism on the way of Saint James the current situation. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanata, K. What Makes Tourists’ Experience Spiritual? A Case Study of a Buddhist Sacred Site in Koyasan, Japan. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2021, 9, 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mourtazina, E. Beyond the horizon of words: Silent landscape experience within spiritual retreat tourism. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 14, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.; O’Regan, M. Faith manifest: Spiritual and Mindfulness Tourism in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Religions 2020, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, G. Spiritual awakening leading to a search for meaning through travel. Int. J. Tour. Spiritual. 2017, 2, 10–23. Available online: http://ijtcs.usc.ac.ir/article_46881_fd30c0e2baba00e8a62b8db9491ff976.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Norman, A.; Pokorny, J.J. Meditation retreats: Spiritual tourism well-being interventions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holladay, P.J. Transformative Potential of a Short-term Mission Trip Experience. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2018, 6, 29–36. Available online: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/vol6/iss3/5 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Lewis-Cameron, A.; Brown-Williams, T.; Jordan-Miller, L.A. Transformative Tourism Curriculum: Perspectives from Caribbean Millennials. J. East. Caribb. Stud. 2020, 45, 43–67. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/9077dc588742c85189d312b2e1fdd2ce/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=38731 (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Young, T.; Hanley, J.; Lyons, K.D. Mediating global citizenry: A study of facilitator-educators at an Australian university. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2017, 42, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolderston, A.; Morgan, S. Global Impact: An Examination of a Caribbean Radiation Therapy Student Placement at a Canadian Teaching Hospital. J. Med. Imaging. Radiat. Sci. 2010, 41, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T. The Transformative Power of Travel? Four Social Studies Teachers Reflect on Their International Professional Development. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 2015, 43, 345–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, D. Generation Z talking: Transformative experience in educational travel. J. Tour. Futures 2019, 5, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gibson, H.J. Long-Term Impact of Study Abroad on Sustainability-Related Attitudes and Behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambrell, J.A. Travel for Transformation: Embracing a Counter-Hegemonic Approach to Transformative Learning in Study Abroad. J. Multicult. Aff. 2018, 3. Available online: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/jma/vol3/iss1/1 (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Gambrell, J.A. A critical race analysis of travel for transformation: Pedagogy for the privileged or vehicle for critical social transformation? J. Ethnogr. Qual. Res. 2016, 11, 99–116. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1258387 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Hall, T.; Gray, T.; Downey, G.; Sheringham, C.; Jones, B.; Power, A.; Truong, S. Jafari and Transformation: A model to enhance short-term overseas study tours. Front. Interdiscip. J. Study Abroad 2016, 27, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, F.; King, B.; Lockstone-Binney, L.; Junek, O. Global global, acting local: Volunteer tourists as prospective community builders. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, C.V.; Scheffer, A.B.B.; Closs, L.Q. Volunteer tourism, transformative learning and its impacts on careers: The case of Brazilian volunteers. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedneck, B. Beyond the glittering golden Buddha statues: Difference and self-transformation through Buddhist volunteer tourism in Thailand. Journeys J. Travel Travel Writ. 2017, 18, 57–78. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20173260365 (accessed on 23 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Knollenberg, W.; McGehee, N.G.; Boley, B.B.; Clemmons, D. Motivation-based transformative learning and potential volunteer tourists: Facilitating more sustainable outcomes. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 922–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, J.; Ferreira, M.R.; Casais, B. Empowering the Community or Escape Daily Routine—A Voluntourism Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molz, J.G. Making a difference together: Discourses of transformation in family voluntourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 805–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.Y.; Lehto, M.R. Vacation as a Public Health Resource: Toward a Wellness Centered Tourism Design Approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 935–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, E. Tourism and wellbeing: Transforming people and places. Int. J. Spa Wellness 2018, 1, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, H.; Cheer, J.M. Yoga tourism: Commodification and western embracement of eastern spiritual practice. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, P. Stretching into the Shadows: Unlikely Alliances, Strategic Syncretism, and De-Post-Colonizing Yogaland’s ‘Yogatopia(s)’. Asian Ethnol. 2019, 78, 373–401. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337907197_Stretching_into_the_Shadows_Unlikely_Alliances_Strategic_Syncretism_and_De-Post-Colonizing_Yogaland’s_Yogatopias (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Soltani, S.; Ghorbanian, M.; Tham, A. South to South Medical Tourists, the Liminality of Iran? J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 22, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Erskine, K. Tropophilia: A Study of People, Place and Lifestyle Travel. Mobilities 2014, 9, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deville, A.; Wearing, S.; McDonald, M. WWOOFing in Australia: Ideas and lessons for a de-commodified sustainability tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajiao, D.; Leung, Y.; Larson, L.R.; Tejedo, P.; Benayas, J. Tourists’ motivations, learning, and trip satisfaction facilitate pro-environmental outcomes of the Antarctic tourist experience. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 37, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, M.; Moore, R. An evaluation of a leadership development programme for women in STEMM in Antarctica. Polar J. 2018, 8, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burwell, J. Imagining the beyond: The social and political fashioning of outer space. Space Policy 2019, 48, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkwater, K.; Massullo, B.; Dagnall, N.; Laythe, B.; Boone, J.; Houran, J. Understanding Consumer Enchantment via Paranormal Tourism: Part I—Conceptual Review. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2022, 63, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponting, S.S. Birth country travel and adoptee identity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 93, 103354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimtun, B.; Morgan, N. Proposing paradigm peace: Mixed methods in feminist tourism research. Tour. Stud. 2012, 12, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddou, G.; Mendenhall, M.E.; Ritchie, B.J. Leveraging Travel as a Tool for Global Leadership Development. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 39, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, U.; Gretzel, U. Tourism 4.0 technologies and tourist experiences: A human-centered design perspective. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batle, J.; Robledo, M.A. Systemic crisis, weltschmerz and tourism: Meaning without incense during vacations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1386–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, G.; Jose, S. Solo Travel: A Transformative Experience for Women. Empower- J. Soc. Work 2020, 1, 44–56. Available online: http://kaps.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Solo-Travel-A-Transformative-Experience-for-Women-by-Gilda-Mani-and-Sonny-Jose.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Chen, G.; Huang, S.; Hu, X. Backpacker Personal Development, Generalized Self-Efficacy, and Self-Esteem: Testing a Structural Model. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fozdar, F. Social Transformation and the Individual: Opportunities and Limitations. J. Intercult. Stud. 2018, 39, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Brown, L. Dwelling-mobility: A theory of the existential pull between home and away. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 81, 102880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovich, M.; Saayman, M. Authentic economy shaping transmodern tourism experience. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Dance 2015, 21, 24–36. Available online: https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC182970 (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Ross, S.L. The Making of Everyday Heroes: Women Experiences with Transformation and Integration. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2019, 59, 499–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateljevic, I. Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re)generating the potential ‘new normal’. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, S.; Laing, J. Trends and Directions in Tourism and Positive Psychology. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimiás, A.; Mitev, A.; Michalkó, G. The multidimensional realities of mediatized places: The transformative role of tour guides. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, S.; Simoni, V.; Isnart, C. Tourism and transformation: Negotiating metaphors, experiencing change. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2014, 12, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, A. The role of travel and mobility in processes of identity formation among the Positanesi. Tour. Stud. 2014, 14, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Sigala, M. Shareable tourism: Tourism marketing in the sharing economy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawjin, J.; Biran, A. Negative emotions in tourism: A meaningful analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2386–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbens, E.H.; Jóhannesson, G.T. Tending to destinations: Conceptualising tourism’s transformative capacities. Tour. Stud. 2019, 19, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengyel, A. Authenticity, mindfulness and destination liminoidity: A multi-level model. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022, 47, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrhein, S.; Hospers, G.; Reiser, D. Transformative Effects of Overtourism and COVID-19-Caused Reduction of Tourism on Residents—An Investigation of the Anti-Overtourism Movement on the Island of Mallorca. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.; Pham, T. Indigenous residents, tourism knowledge exchange and situated perceptions of tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottler, J.A. The Therapeutic Benefits of Structured Travel Experiences. J. Clin. Act. Assign. Handouts Psychother. Pract. 2001, 1, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, E. Temporality and biography in tourism: A qualitative longitudinal approach. J. Qual. Res. Tour. 2020, 1, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L. What motivates and hinders people from travelling alone? A study of solo and non-solo travellers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2458–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regions | Articles | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Europe | 121 | United Kingdom (40); Italy (10); Portugal (10); Spain (8); Austria (6); The Netherlands (5); Finland (4); Germany (4); Norway (4); Croatia (3); France (3); Ireland (3); Lithuania (3); Poland (3); Sweden (3); Denmark (2); Hungary (2); Switzerland (2); Belgium (1); Greece (1); Iceland (1); Latvia (1); Serbia (1); Slovenia (1) |

| North America | 84 | United States (73); Canada (11) |

| Oceania | 61 | Australia (49); New Zealand (12) |

| Asia and Pacific | 33 | China (13); Hong Kong (4); Malaysia (3); Thailand (3); India (2); Japan (2); Singapore (2); Indonesia (1); Myanmar (1); Vietnam (1); South Korea (1) |

| Africa | 10 | South Africa (8); Ghana (1); Kenya (1) |

| Middle East | 6 | Israel (3); Iran (2); Jerusalem (1) |

| South America | 6 | Brazil (3); Trinidad and Tobago (2); Ecuador (1) |

| TC | TP WOS | % | TP EBSCO | % | TP SD | % | TP GS | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.8 |

| ≥300 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.7 |

| ≥200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2.1 |

| ≥100 | 5 | 2.2 | 2 | 2.4 | 4 | 5.2 | 16 | 6.7 |

| ≥50 | 14 | 6.1 | 3 | 3.6 | 3 | 3.9 | 41 | 17.1 |

| ≥25 | 28 | 12.1 | 12 | 14.5 | 17 | 22.1 | 37 | 15.4 |

| ≥10 | 44 | 19.1 | 12 | 14.5 | 17 | 22.1 | 43 | 17.9 |

| ≥5 | 30 | 13.0 | 13 | 15.7 | 10 | 13.0 | 31 | 12.9 |

| <5 | 55 | 23.8 | 21 | 25.3 | 18 | 23.4 | 47 | 19.6 |

| 0 | 53 | 22.9 | 20 | 24.1 | 6 | 7.8 | 14 | 5.8 |

| Total articles | 231 | 100 | 83 | 100 | 77 | 100 | 240 | 100 |

| Total citations | 4390 | 100 | 1186 | 100 | 2635 | 100 | 11,918 | 100 |

| WOS | Title | Authors | Journal | TC | C/Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research [203] | Sigala, M. | Journal of Business Research | 398 | 199 |

| 2. | This trip really changed me: Backpackers’ Narratives of Self-Change [14] | Noy, C. | Annals of Tourism Research | 345 | 19.16 |

| 3. | Tourism: A catalyst for existential authenticity [30] | Brown, L. | Annals of Tourism Research | 170 | 18.88 |

| 4. | The transformative power of the international sojourn: an ethnographic study of the international student experience [16] | Brown, L. | Annals of Tourism Research | 156 | 12 |

| 5. | The Educational Benefits of Travel Experiences: A Literature Review [205] | Stone, M.J; Petrick, J.F. | Journal of Travel Research | 120 | 13.33 |

| EBSCO | Title | Authors | Journal | TC | C/Y |

| 1. | Applying a transformative learning framework to volunteer tourism [207] | Coghlan, A.; Gooch, M. | Journal of Sustainable Tourism | 111 | 10.09 |

| 2. | The Educational Benefits of Travel Experiences: A Literature Review [205] | Stone, M.J; Petrick, J.F. | Journal of Travel Research | 105 | 11.66 |

| 3. | Making magic consumption: A study of white-water river rafting [13] | Arnould, E.; Price, L.; Otnes, C. | Journal of ContemporaryEthnography | 85 | 3.69 |

| 4. | Asymmetrical Dialectics of Sustainable Tourism: Toward Enlightened Mass Tourism [206] | Weaver, D.B. | Journal of Travel Research | 77 | 9.62 |

| 5. | Exploring the Motivations of BASE JUMPERS: Extreme Sport Enthusiasts [18] | Allman, T, L. et al. | Journal of Sport & Tourism | 64 | 4.92 |

| SD | Title | Authors | Journal | TC | C/Y |

| 1. | Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research [203] | Sigala, M. | Journal of Business Research | 470 | 235 |

| 2. | This trip really changed me: Backpackers’ Narratives of Self-Change [14] | Noy, C. | Annals of Tourism Research | 425 | 23.61 |

| 3. | Tourism: A catalyst for existential authenticity [30] | Brown, L. | Annals of Tourism Research | 173 | 19.22 |

| 4. | The transformative power of the international sojourn: an ethnographic study of the international student experience [16] | Brown, L. | Annals of Tourism Research | 141 | 10.84 |

| 5. | Tourism and spirituality: A Phenomenological analysis [77] | Willson, G. B.; McIntosh, A. J.,Zahra A.L | Annals of Tourism Research | 119 | 13.22 |

| GS | Title | Authors | Journal | TC | C/Y |

| 1. | Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research [203] | Sigala, M. | Journal of Business Research | 1061 | 530.5 |

| 2. | This trip really changed me: Backpackers’ Narratives of Self-Change [14] | Noy, C. | Annals of Tourism Research | 913 | 50.72 |

| 3. | The transformative power of the international sojourn: an ethnographic study of the international student experience [16] | Brown, L. | Annals of Tourism Research | 417 | 32.07 |

| 4. | Tourism: A catalyst for existential authenticity [30] | Brown, L. | Annals of Tourism Research | 333 | 37 |

| 5. | Wellness tourists: in search of transformation [24] | Voigt, C.; Brown, G.; Howat, G. | Tourism Review | 321 | 29.18 |

| Authors | Country | University | TP | TC | WOS | EBSCO | SD | GS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lehto, X. Y. | United States | Purdue University | 5 | 816 | 244 | 79 | 29 | 464 |

| Laing, J. H. | Australia | La Trobe University | 4 | 414 | 114 | 44 | 53 | 203 |

| Del Chiappa, G. | Italy, South Africa | University of Sassari; University of Johannesburg | 5 | 388 | 110 | 4 | 44 | 230 |

| McGehee, N. | United States | Virginia Tech University | 4 | 277 | 69 | 6 | 30 | 172 |

| Sigala, M. | Australia | University of South Australia | 3 | 2322 | 485 | 0 | 558 | 1279 |

| Brown, L. | United Kingdom | Bournemouth University | 3 | 1419 | 333 | 0 | 324 | 762 |

| Kirillova, K. | Hong Kong | Hong Kong Polytechnic University | 4 | 652 | 198 | 76 | 0 | 378 |

| Cai, L. | United States | Purdue University | 3 | 652 | 198 | 76 | 0 | 378 |

| Morgan, N. | United Kingdom | Surrey University | 3 | 644 | 146 | 45 | 131 | 322 |

| Filep, S. | New Zealand | University of Otago | 3 | 349 | 99 | 49 | 0 | 201 |

| Pung, J. M. | Italy | University of Cagliari | 3 | 231 | 64 | 4 | 44 | 119 |

| Soulard, J. | United States | Virginia Tech University | 3 | 149 | 30 | 6 | 30 | 83 |

| Co-Author | Articles | Countries | Universities and Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kirillova, K.; Lehto, X.Y.; Cai, L. | 3 | USA; Hong Kong | Hong Kong Polytechnic University; Purdue University |

| Pung, J. M.; Del Chiappa, Giacomo | 3 | Italy; New Zealand; South Africa | University of Cagliari; University of Otago; University of Sassari; University of Johannesburg |

| Soulard, J.; McGehee, N.; Stern, M. J./Soulard, J.; McGehee, N. | 2/1 | USA | University of Illinois; Virginia Tech University |

| Vidickienė, D.; Gedminaitė-Raudonė Ž.; Vilkė, R. | 2 | Lithuania | Institute of Economics and Rural Development, Vilnius |

| Ryzdik, A.; Morgan, N.; Sedgley, D. | 2 | UK | Cardiff Metropolitan University |

| Neuhofer, B.; Celuch, K. | 2 | Austria; Poland | Fachhochschule Salzburg; Nicolaus Copernicus University |

| Godovykh, M.; Tasci, A. D. A. | 2 | USA | University of Central Florida |

| Laing, J. H.; Frost, W. | 2 | Australia | La Trobe University |

| Robledo, M. A.; Batle, J. | 2 | Spain | University of the Balearic Islands |

| McGehee N.; Knollenberg, W. | 2 | USA | Virginia Tech University |

| Ivanovic, M.; Sandile L. M. | 2 | South Africa | University of Johannesburg |

| Stone, G. A.; Duffy, L. N. | 2 | USA | Clemson University |

| Top Journals | Q | Jh | JIF | JCI | Top Publishers | Articles | % | TC | TT h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annals of Tourism Research | Q1 | 187 | 9011 | 2.85 | Taylor and Francis Ltd. | 26 | 10.4 | 5828 | 21 |

| Tourism Management Perspectives | Q1 | 54 | 6586 | 1.58 | Elsevier USA | 13 | 5.2 | 1176 | 9 |

| Journal of Sustainable Tourism | Q1 | 114 | 7968 | 1.51 | Taylor and Francis Ltd. | 11 | 4.4 | 1202 | 9 |

| Tourism Management | Q1 | 216 | 10,967 | 2.96 | Elsevier Ltd. | 9 | 3.6 | 707 | 7 |

| Tourism Recreation Research | Q1/Q2 | 50 | - | 0.76 | Taylor and Francis Ltd. | 9 | 3.6 | 349 | 5 |

| Sustainability | Q1/Q2 | 109 | 3251 | 0.56 | MDPI AG | 9 | 3.6 | 290 | 4 |

| Tourist Studies | Q1 | 50 | 1904 | 0.55 | SAGE Publications Ltd. | 8 | 3.2 | 493 | 8 |

| Journal of Travel Research | Q1 | 145 | 10982 | 2.99 | SAGE Publications Ltd. | 7 | 2.8 | 1408 | 7 |

| Current Issues In Tourism | Q1 | 82 | 7430 | 1.99 | Taylor and Francis Ltd. | 7 | 2.8 | 598 | 7 |

| Journal of Business Research | Q1 | 217 | 7550 | 1.87 | Elsevier Inc. | 7 | 2.8 | 2265 | 6 |

| Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing | Q1 | 82 | 7564 | 1.98 | Routledge | 7 | 2.8 | 274 | 4 |

| Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management | Q1 | 45 | 5959 | 1.44 | Elsevier BV | 6 | 2.4 | 85 | 4 |

| Tourism Geographies | Q1 | 73 | 6640 | 1.31 | Routledge | 5 | 2 | 315 | 5 |

| Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education | Q2 | 29 | 1762 | 0.94 | Oxford Brookes University | 5 | 2 | 153 | 4 |

| Journal of Tourism Futures | Q2 | 21 | - | 0.88 | Emarald Group Publishing Ltd. | 5 | 2 | 89 | 4 |

| Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change | Q2 | 31 | 2041 | 0.62 | Taylor and Francis Ltd. | 4 | 1.6 | 107 | 4 |

| Journal of Destination Marketing & Management | Q1 | 27 | 6952 | 1.84 | Elsevier Ltd. | 4 | 1.6 | 95 | 3 |

| Religions | Q1 | 50 | - | 1.65 | MDPI | 4 | 1.6 | 37 | 2 |

| Journal of Outdoor Recreation And Tourism | Q2 | 27 | 2803 | 0.85 | Elsevier BV | 4 | 1.6 | 19 | 2 |

| International Journal of Religious Tourism & Pilgrimage | Q1/Q4 | 7 | - | - | Technological University Dublin | 4 | 1.6 | 4 | - |

| Journal of Ecotourism | Q2 | 40 | - | - | Taylor and Francis Ltd. | 3 | 1.2 | 271 | 3 |

| 14 others | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (14) | 0.8 (14) | - | - |

| 65 others | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (65) | 0.4 (65) | - | - |

| Total 101 Journals | 250 | 100 | 20,129 |

| TOP 20 JOURNALS | ANNUAL NUMBER OF PAPERS PUBLISHED IN TOP JOURNALS | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | TOTAL | |

| Annals of Tourism Research | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 26 | |||

| Tourism Management Perspectives | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 13 | ||||||||||

| Journal of Sustainable Tourism | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |||||||

| Tourism Management | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 9 | |||||||||

| Tourism Recreation Research | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 | |||||||||

| Sustainability | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||||

| Tourist Studies | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||||||||

| Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | ||||||||||||

| Journal of Business Research | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 | |||||||||||

| Journal of Travel Research | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||

| Current Issues in Tourism | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||||

| Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | |||||||||||

| Tourism Geographies | 4 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||||||

| Journal of Tourism Futures | 4 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||||||

| Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | ||||||||||||

| Religions | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Journal of Destination Marketing & Management | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||

| International Journal of Religious Tourism & Pilgrimage | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| Total | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 23 | 30 | 14 | 154 |

| Journal Subject | % | Journal Categories | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Sciences | 36 | Geography, Planning and Development | 14.1 |

| Social and Political Science | 4.9 | ||

| Cultural Studies | 4.3 | ||

| Education | 3.3 | ||

| Anthropology | 2.2 | ||

| Transportation | 2.2 | ||

| Development | 1.6 | ||

| Communication | 1.1 | ||

| Demography | 0.5 | ||

| Gender Studies | 0.5 | ||

| Health | 0.5 | ||

| Linguistics and Language | 0.5 | ||

| Social Sciences (miscellaneous) | 0.5 | ||

| Urban Studies | 0.5 | ||

| Business, Management and Accounting | 30.9 | Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management | 21.2 |

| Strategy and Management | 2.7 | ||

| Marketing | 2.2 | ||

| Business and International Management | 0.5 | ||

| Management of Technology and Innovation | 0.5 | ||

| Organizational Behaviour and Human Resource Management | 0.5 | ||

| Arts and Humanities | 8.8 | Literature and Literary Theory | 2.2 |

| Philosophy | 1.6 | ||

| Religious Studies | 1.6 | ||

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 1.1 | ||

| History | 1.1 | ||

| Visual Arts and Performing Arts | 1.1 | ||

| Environmental Science | 8.1 | Management, Monitoring, Policy and Law | 3.3 |

| Nature and Landscape Conservation | 2.7 | ||

| Environmental Science (miscellaneous) | 1.6 | ||

| Ecology | 1.1 | ||

| Global and Planetary Change | 0.5 | ||

| Health | 0.5 | ||

| Pollution | 0.5 | ||

| Toxicology and Mutagenesis | 0.5 | ||

| Psychology | 5.9 | Social Psychology | 3.3 |

| Applied Psychology | 1.1 | ||

| Clinical Psychology | 1.1 | ||

| Experimental and Cognitive Psychology | 0.5 | ||

| Neuropsychology and Physiological Psychology | 0.5 | ||

| Earth and Planetary Sciences | 3.7 | Earth and Planetary Sciences (miscellaneous) | 1.1 |

| Earth-Surface Processes | 0.5 | ||

| Geology | 0.5 | ||

| Space and Planetary Science | 0.5 | ||

| Medicine | 2.9 | Environmental and Occupational Health | 0.5 |

| Medicine (miscellaneous) | 0.5 | ||

| Nuclear Medicine and Imagining | 0.5 | ||

| Psychiatry and Mental Health | 0.5 | ||

| Public Health | 0.5 | ||

| Radiology | 0.5 | ||

| Computer Science | 0.7 | Computer Science Applications | 0.5 |

| Information Systems | 0.5 | ||

| Economics, Econometrics and Finances | 0.7 | Economics and Econometrics | 0.5 |

| Energy | 0.7 | Energy Engineering and Power Technology | 0.5 |

| Energy, Sustainability and the Environment | 0.5 | ||

| Engineering | 0.7 | Engineering (miscellaneous) | 0.5 |

| Health Professions | 0.7 | Radiological and Ultrasound Technology | 0.5 |

| Top Universities | Articles | Ref. Times |

|---|---|---|

| Griffith University | 10 | 15 |

| University of Otago | 7 | 12 |

| Bournemouth University | 7 | 10 |

| Purdue University | 6 | 10 |

| University of Johannesburg | 6 | 9 |

| University of South Australia | 6 | 8 |

| The Hong Kong Polytechnic University | 6 | 7 |

| Southern Cross University | 6 | 7 |

| University of Georgia | 5 | 7 |

| Nottingham University | 5 | 6 |

| University of Sassari | 5 | 5 |

| Brigham Young University | 4 | 12 |

| Virginia Tech University | 4 | 8 |

| The University of Newcastle | 4 | 7 |

| Arizona State University | 4 | 6 |

| University of British Columbia | 4 | 5 |

| La Trobe University | 4 | 5 |

| Lisbon University Institute | 4 | 5 |

| Leeds Beckett University | 4 | 4 |

| Edith Cowan University | 4 | 4 |

| Funded | Not Funded | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Articles | 53 | 197 | 250 |

| % | 21.2% | 78.8% | 100% |

| Keywords | TLS | Occurrences |

|---|---|---|

| Travel | 857 | 116 |

| Outcome | 624 | 69 |

| Nature | 469 | 60 |

| Motivation | 552 | 56 |

| Dimension | 455 | 53 |

| Community | 435 | 52 |

| Journey | 331 | 46 |

| Student | 337 | 45 |

| Pilgrimage | 431 | 38 |

| Transformative experience | 278 | 38 |

| Benefit | 315 | 36 |

| Transformative learning | 306 | 35 |

| Authenticity | 282 | 34 |

| Engagement | 302 | 33 |

| Tourist experience | 268 | 32 |

| Articles | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Main theme | 129 | 51.6 |

| Secondary theme | 121 | 48.4 |

| Classification | Articles | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research methods | Qualitative analysis | 202 | 80.8 |

| Quantitative analysis | 24 | 9.6 | |

| Mixed Methods | 24 | 9.6 | |

| Total | 250 | 100 | |

| Research perspective | Tourists | 165 | 66 |

| General | 44 | 17.6 | |

| Multiple/Holistic | 21 | 8.4 | |

| Stakeholders | 14 | 5.6 | |

| Hosts/Residents | 6 | 2.4 | |

| Total | 250 | 100 |

| Type of Tourism | Articles | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural | Cultural-only (3); Indigenous tourism (5); Aboriginal tourism (1); Dark tourism (7); Temple stays (1); Rural (1); Festival and events (13)—sport events (2); Creative (2); Flamenco tourism (1); Film tourism (2); Food and wine tourism (1); Food-only tourism (1); Slum tourism (1). | 39 | 15.6 | [217,218,219]; [63,103,137,167,220]; [19]; [17,36,115,135,152,175,221]; [222]; [223]; [40,41,100,102,108,110,119,127,154,164,185,224,225]; [68,226]; [227]; [150,151]; [124]; [228]; [31]. |

| Nature-based | Nature-based only (10); Cultural (1); Adventure-only (3); Eco-tourism (7) - eco-tourism only (4), community based (2), marine (1); Community-based only (1); Frontier (1); Island (1); Conscious travel (1); Sustainable (2); Outdoor (1); Equestrian (1); Wellness and fitness (2), Extreme sports (2); Adventure sports (1); Mountaineering and cycling (1). | 35 | 14 | [46,48,58,93,123,171,229,230,231,232]; [233]; [89,182,234]; [186,235,236,237]; [26,94]; [59]; [170]; [105]; [149]; [82]; [238,239]; [92]; [109]; [96,161]; [18,163]; [13]; [53]. |

| Religious | Religious-only (3); Pilgrimage (12)—motorbiking (1); Spiritual (13) -Christian (1); Shamanic (1). | 29 | 11.6 | [165,240,241]; [138,142,216,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250]; [57,77,116,144,176,251,252,253,254,255,256,257]; [258]; [140]. |