1. Introduction

“Performance with purpose is about the character of our company and managing PepsiCo with an eye toward not only short-term priorities, but also long-term goals, recognizing that our success—and the success of the communities we serve and the wider world—are inextricably bound together”.

Indra Nooyi

In 2006, PepsiCo’s then CEO Indra Nooyi rolled out a new business orientation named “performance with purpose”. This is a strategic initiative that redefines business success to include the four equally important pillars of sustainability: financial, human, environmental, and talent. She later explained that the principle of performance with purpose lies in the word “with”. PepsiCo’s long-term outlook is only possible when its financial goals are tied to the other three pillars within an interconnected ecosystem. As an idea that was far ahead of its time, Nooyi’s message on business’s social responsibility beyond profit generation was not lost on the corporate world. Fast forward to 2019: 181 CEOs of major U.S. companies signed a corporation purpose statement issued by the Business Roundtable: “We share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders…each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to deliver values to all of them, for the future success of our companies, our communities and our country” [

1]. The statement generated a massive media reaction for its stunning reversal from a statement Business Roundtable had issued in 1997 that supported shareholder-wealth maximization as the paramount purpose of businesses. The 2019 purpose statement is undoubtedly an important signal of how the business world is rethinking its primary role and accountability toward society [

2]. A leap forward from a single voice to 181 signatures is not insignificant, but it is still a small number out of the total number of companies in the United States. We cannot confidently say, yet, that performance with purpose has become mainstream when a large majority of business leaders in the C-suite are still hesitating to implement it. In fact, we still see companies represented at every point along the “social responsibility” spectrum [

3]. This begs the questions of why such persistently diverse views on the role of a corporation and varying CSR responses exist among corporate leaders.

For decades, the broad questions of why firms march at different paces or even to different tunes when it comes to CSR engagement have fascinated scholars [

4,

5]. Academic research on heterogeneity in CSR falls under two broad camps, one with a macro-focus and the other focused on the micro-foundations of CSR strategies. Both camps have a proliferation of theoretical perspectives that provide invaluable insight on CSR responses. However, both literatures seem to have cast much less attention on the role of decision-making processes in shaping diverse CSR responses. Managerial cognition research has long argued that firm’s CSR activities are not a direct result of external demands but, rather, an outcome of sense-making processes that shape how the world is perceived by key decision makers [

6,

7,

8]. Thus, the omission of the CSR decision makers and their information processing has limited our ability to fully address the questions of why and how firms engage CSR differently. In the following sections, we briefly review the main contributions of the macro and micro perspectives, which are the foundations of this paper. We then propose a CSR decision-frame model to bring the decision makers back into the picture and elaborate on the role of different mental models in shaping the diversity of CSR strategies.

The macro approach to CSR research focuses on institutional and firm drivers of CSR activities. In particular, this perspective suggests that both external and internal factors drive a firm’s CSR investment, based on the dominant theoretical traditions of institutional theory, stakeholder theory, agency theory, and resource-based theory [

5,

9]. For instance, institutional determinants can influence a business’s CSR strategies. The strategic intent is to achieve legitimacy and stability by conforming to various institutional norms and expectations [

10]. Another important external driver is a firm’s stakeholders, who have diverse needs, demands, and influencing power over firms [

11,

12]. Naturally, firms cultivate unique relationships with various stakeholder groups—depending on perceived primacy and urgency—through various CSR initiatives [

13]. Additionally, resource-based theories of CSR point to firm-level factors as predictors. Firms are expected to engage in CSR to achieve a competitive advantage [

14,

15]. Thus, CSR strategies likely align with a firm’s unique resources and core competencies [

16,

17].

In addition to different macro-level drivers, these diverse theoretical perspectives have also been insightful for understanding the assumptions underlying various CSR initiatives. The differences in assumptions about the fundamental role of business, the relationship between business and society, and what constitute legitimate claims on the firm are thought to have led to different interpretations of “social responsibility” and, thus, different CSR strategic orientations [

18,

19]. However, the paradigm level of analysis has limitations regarding fully capturing the complex and dynamic nature of CSR diversity. Additionally, despite the valuable contributions to understanding CSR heterogeneity, this line of inquiry largely neglects the human factors relevant to CSR activities. The role of firm executives, who are the ultimate decision makers of CSR strategies, has been largely ignored [

20,

21].

As an alternative approach, CSR research with a micro-foundation lens addresses questions about how strategic decision makers and their individual characteristics affect a firm’s CSR choices [

22,

23]. As Votaw accurately stated, “Corporate social responsibility means something, but not always the same thing to everybody” [

24] (p. 25). Thus, it is impossible to fully understand diverse CSR choices without exploring the processes associated with how these individuals make sense of CSR issues during their decision-making processes [

21]. It is not surprising that there has been an explosion of research on leadership CSR in recent decades. Zhao et al.’s (2022) bibliometric review reported that 1432 articles with the co-theme of leadership and CSR were published from 1994 to 2020 [

25]. A bourgeoning amount of research has explored the relationship between diverse organizational leaders’ characteristics (e.g., executives’ personalities, values, and leadership styles) and firms’ CSR engagement [

25,

26,

27]. Upper echelons theory, an overarching process lens depicting the central role of decision-makers, provides the micro CSR literature’s foundational framework [

28,

29]. The core premise of the theory is that a firm’s strategic choices are a reflection of the individual characteristics of its executives [

29]. As

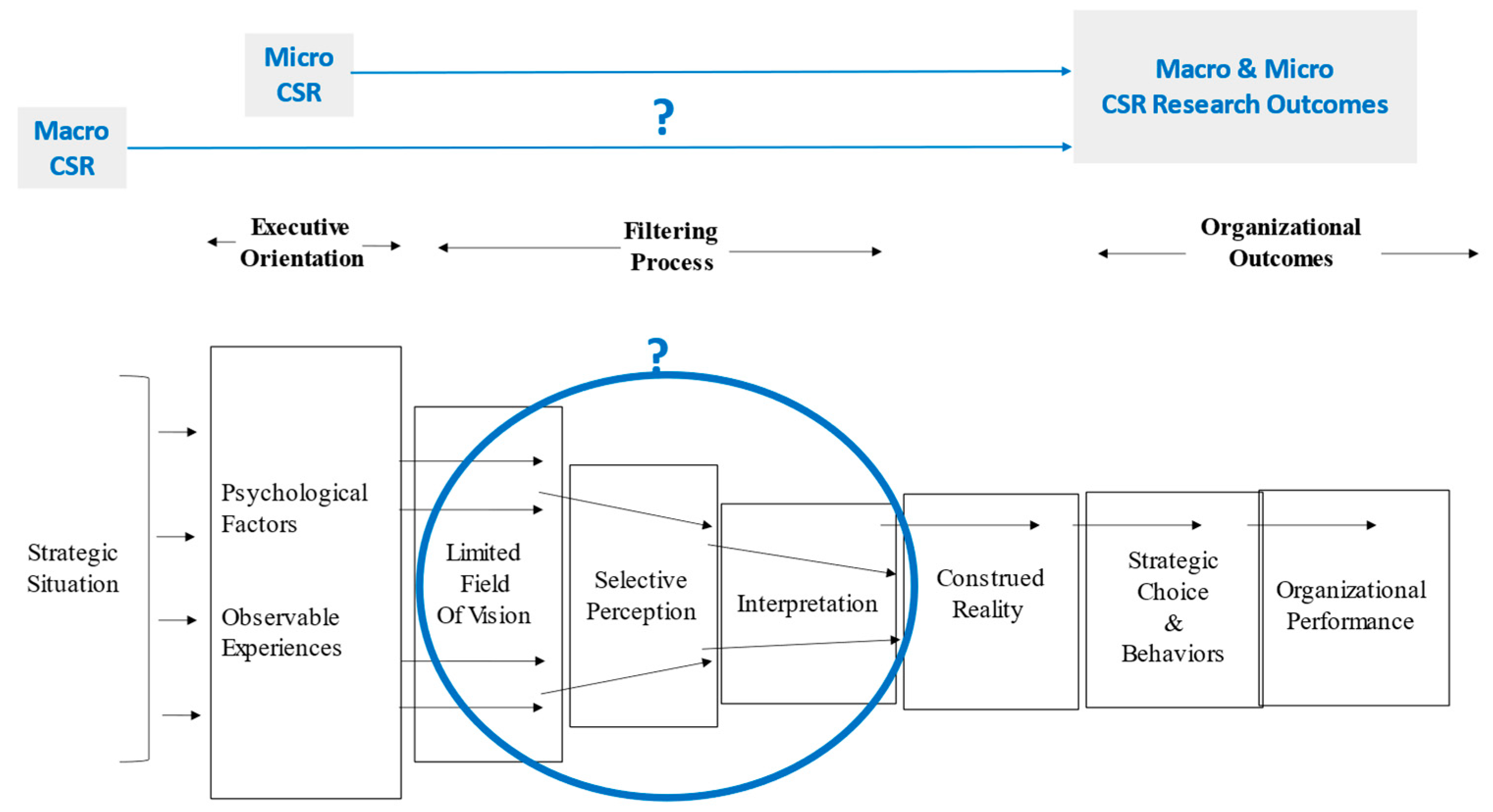

Figure 1 shows, corporate leaders operate within the constraints of bounded rationality, and their individual psychological orientations inform their interpretations and construal of the strategic situation [

29,

30].

Despite the proliferation of academic inquiry, most research in the micro-CSR research domain focuses on executives’ varying individual attributes and social values (executive orientation) as motivating factors, and the corresponding implications for strategic choices and organizational performance (organizational outcomes). As we show in the blue font in

Figure 1, there is a striking gap in the CSR literature regarding how executives’ motivational values and leadership styles actually affect their information processing and decision-making related to CSR (filtering process).

Figure 1 depicts an integration of the macro and micro streams of research and demonstrates the complementarity of these lenses. Whereas the macro approach in the CSR literature provides insights into principal assumptions and organizational determinants, conversations in micro-foundations illuminate the process underlying CSR strategic diversity by highlighting the role of executives as strategic decision makers. Our synthesized framework also reveals a significant omission in the extant research: How do strategic leaders make sense of CSR-related issues and how can we explain the variability in their interpretations of the environmental signals [

31]. Scholars are voicing their concerns and calling for more attention to unpacking the black box of strategic information processing and how it shapes decisions and responses [

6,

20,

25,

31,

32].

To address this gap in current views on predictors of CSR diversity, this study proposes a CSR decision-frame model to examine the CSR decision-making process and understand how executives interpret the principal issues concerning CSR differently—a process that ultimately leads to diverse CSR strategic choices. Strategic decisions involve high levels of complexity and uncertainty. This is particularly true for CSR decisions, which often involve interconnected and competing concerns from a diverse range of interest groups and stakeholders [

31]. Executives “face a great deal of ambiguity in understanding the issues, the implications of these issues for their organizations, and ways to respond to these issues” [

33] (p. 683). The managerial cognition literature has long established the decision frame as the cognitive mechanism through which managers filter complex information, reduce uncertainty, and make sense of the business world heuristically [

33,

34,

35]. Drawing from this literature, we develop a CSR-specific decision frame, which is a mental template defined by two dimensions:

cognitive content and

cognitive structure.

Cognitive content contains three CSR principles (pillars), articulated as the fundamental assumptions of CSR in macro research: corporate purpose (C), corporate stakeholder scope (S), and lead responsibly (R). We contend that the C, S, and R pillars represent the essential questions executives must address during the strategic decision-making process, which, in turn, guides their strategic orientations. Furthermore, the

cognitive structure of each pillar is conceptualized as a continuum representing a wide spectrum of executive interpretations of respective principal questions. Thus, an individual executive’s CSR decision frame is a configuration of the responses to each of the three principles. This multidimensional

cognitive structure of the decision frame allows for a broader bandwidth than the extant paradigm perspectives to capture more nuanced variations of executive mindsets regarding CSR.

By integrating the macro- and micro-CSR literature via a managerial cognition lens, we contribute to conversations about heterogeneity in CSR strategic responses in three ways.

First, a CSR decision frame provides a process lens to understand the important question of why executives respond differently to CSR investment. The key utility of a three-pillar mental template is to highlight the cognitive determinants of executives’ influence on firm CSR strategies. Instead of a decision black box that is explained using assumptions, this paper offers an operationalizable mechanism articulating how a leader’s individual values and other psychological orientations are translated into CSR strategic choices via motivated information processing. Thus, we contribute to the CSR research by proposing a more proximate driver of firm CSR strategic choice than an executive psychological orientation.

The second contribution has to do with the multiplicity in the characterization of the CSR decision frame. We build

cognitive content with three essential principles (C, S, and R) that are generally articulated as assumptions in prominent CSR theories. However, not every theory explicitly makes distinctions among the three principles. Further, recent researchers of CSR theories often map these assumptions at a paradigm level [

17,

19,

36]. In contrast, in this study we conceptually differentiate these dimensions and consider the C, S, and R pillars as three distinct CSR principles. Following the trend of recent thinking, we also depict each pillar as a continuum to represent a wide spectrum of managerial mindsets [

37,

38]. Consequently, an individual executive’s decision frame is a configuration of three dimensions. This multifaceted mental template framework is more encompasses and captures a wide range of variations in executive mindsets related to CSR, within and across dimensions and paradigms.

Third, the proposed CSR decision frame contributes to the Upper Echelons Theory (UET) literature [

28,

29]. UET focuses on the role of executive’s individualized construal during the process of strategic decision making. However, it falls short in unraveling cognitive mechanisms related to information processing and decision making that comprise the filtering process. This is mainly because of the challenges of directly measuring an executive’s cognitive process [

39]. Our approach provides both identification of more proximal constructs and a framework for operationalizing and creating measurable variables within a decision-frame model. Empirically capturing a leader’s CSR-related mental models. creates an opportunity to test the relationships between leader attributes and various CSR strategic modes and multidimensional performance [

40].

In the following sections, we first articulate the three-pillar CSR decision frame and important assumptions. We then provide exemplar configurations to illustrate the utility of the CSR decision frame in predicting CSR strategic orientations. Finally, we end with identifying key contributions, presenting study limitations, and proposing a future research agenda.

2. CSR Decision Frame: A Managerial Cognition Lens

2.1. Sense Making via a Decision Frame

Strategy scholars have long argued that managerial cognitive abilities and sense-making processes play a critical role in explaining a firm’s strategic postures and performance outcomes [

41]. The significant contribution of this line of inquiry centers on understanding how managers process information and make important decisions on behalf of the organization [

35]. Sense making is a process where people “engage ongoing circumstances from which they extract cues and make plausible sense retrospectively, while enacting more or less order into those ongoing circumstances” [

42] (p. 409). The managerial cognition lens is rooted in the key notion that managers make sense of the world via mental models (commonly used interchangeable terms are cognitive frames, mindsets, mentaltemplates, and decision frames).Mental models comprise cognitive structures that filter what information gets noticed, how it is processed, and interpretation of the information [

8,

43]. Such selective or filtered information processing has a key functional advantage: it reduces the amount and complexity of information. Thus, it “allows people to deal with uncertainty and ambiguity by creating rational accounts of the world that enable action” [

44] (p. 21). It also means that executives most likely operate on a bounded rationality by developing “subjective representations of the environment that, in turn, drive their strategic decisions and subsequent firm action” [

45] (p. 1395).

At the center of the strategic decision-making process is an executive’s cognitive frame, a “mental template that individuals impose on an information environment to give it form and meaning” [

46] (p. 281). It filters out information deemed irrelevant and guides the executive’s attention toward salient and/or important information to organize and make sense of the signals from a complex and dynamic business environment [

47,

48]. Scholars have applied this managerial cognitive lens to understand CSR strategic decision making, particularly how executives interpret and respond to social and environmental issues. Gröschl et al. investigated how differences in the CEO’s mindset, in the form of cognitive complexity, affect corporate sustainability [

49]. The findings showed that a complex mindset is associated with inclusive understanding of sustainability issues and proactive strategy adaptations. Scholars have also linked various leadership values with different power-motivated mental models, which, in turn, predict different decision outcomes [

50,

51]. Regarding responsible leadership, Waldman emphasized the impact of a responsible mindset in directing the CEO’s strategic attention toward more inclusive stakeholder demands and societal-focused strategic preferences [

21]. These works highlight how decision makers rely on various mental models to navigate often ill-defined CSR-related issues and make sense of complex strategic situations [

52].

However, the extant decision-framing research in the CSR context is still sparse, with a few exceptions [

6,

47,

53]. Researchers have focused primarily on the relationships between a specific type of general mental model (e.g., cognitive complexity) and a particular CSR strategic mode (i.e., high specificity). The literature currently lacks an overarching CSR-specific decision frame that can capture the principal heuristics related to social and environmental issues confronting business leaders. This gap is particularly evident in light of recent advances in both micro- and macro-CSR literature (

Figure 1). The rich research tradition on leadership CSR has built a wide range of links between different leadership values and behavioral styles and a firm’s CSR engagement [

25]. Similarly, macro-CSR researchers have systematically organized the theoretical assumptions and institutional and organizational drivers for CSR activities. What is missing from this literature is explication of the processes through which a leader’s conceptual assumptions flow from leadership attributes to CSR activities into a CSR-specific decision-frame construct (i.e., the filtering process in UET).

2.2. CSR Decision Frame: Content and Structure

In this paper, we aim to synthesize and bridge the micro- and macro-CSR literature with a CSR decision-frame concept that can explain the variations in principles underlying executives’ CSR strategic decision processes. To help address research questions of how executives process CSR-related information, it can be fruitful to identify the characteristics and important nature of the cognitive template executives rely on to filter and process information. The CSR decision frame we propose in this paper is built on Hahn et al.’s interpretation of the

content–structure dual dimensional approach to mental templates [

47]. The first dimension is

cognitive content, which “consists of the things he or she knows, assumes and believes” [

30] (p. 57). The second dimension of the decision frame is

cognitive structure, which describes “how the content is arranged, connected, or studied in the executive’s mind” [

30] (p. 57). We will further elaborate on how we conceptualized the CSR decision frame along these two dimensions.

Cognitive content of a decision frame can be specified at the domain level (e.g., CSR, or entrepreneurship). Within the domain, it will capture decision makers’ ascription of distinctive attributes (basis, dimension, or pillar) used to differentiate complex and ambiguous issues or events into categories [

47]. This

content definition provides a critical direction to build a global CSR decision frame. As the Our goal is to identify within-domain attributes of CSR. Another consideration of the

content is that it needs to be overarching and globally applicable to all decision makers, regardless of their CSR ideology. Windsor used the term “neutral CSR principles” to describe this characteristic of the content [

53]. The author suggested that, for CSR, a phenomenon with contested definitions and lacking consensus among diverse theoretical perspectives, a global CSR decision framework should include that “principles do not automatically work for or against a particular CSR perspective. The set of principles constitutes a philosophical foundation” [

53] (p. 21). Echoing Windsor’s principle-level thinking, Kurucz et al. suggested that a contested conceptual field of CSR needs to establish “a set of questions for unearthing the underlying assumptions of the various approaches in order to build a better (more robust, multidimensional, more compelling)” integrative framework for CSR [

18] (p. 3). Following these content-defining rules, we synthesize diverse CSR perspectives and identify three principles to be included as the decision-frame

content: corporate purpose (C pillar), corporate stakeholders (S pillar), and responsibilities of leaders (R pillar) [

9,

18,

19,

54,

55]. These three attributes are value-neutral by definition, and each represents a set of fundamental questions decision makers need to address (

Table 1). Thus, it is how decision makers answer these principal questions (based on their own ideology and values) that differentiates executives’ individual CSR decision frames. There are different shades of CSR strategies because of the varying CSR decision frames.

Managerial cognition scholars have also stipulated two key properties for the cognitive

structure [

47]: “differentiation—the ability to perceive several dimensions in a stimulus array—and integration—the development of complex connections among the differentiated characteristics” [

56] (p. 274). In other words, a cognitive

structure should clearly identify the number of components (differentiation) within the frame and the degree of interconnectedness among the components (integration) [

46,

47]. Following these principles, we define the CSR decision frame as a configuration of three spectrums (

Figure 2). First, the three pillars within the CSR decision frame—C, S, and R—are conceptually distinctive. This is where we depart from the extant literature, where the assumptions for C, S, and R are often lumped together as a global assumption, or only one or two of the three are included. As explained in detail in the following sections, we contend that each pillar depicts a unique principle concerning CSR and a three-dimensional framework provides both a broad bandwidth and the ability to simultaneously capture more nuanced variations in executive mental maps (with more shades of perspectives). Second, the structure of a CSR decision frame is characterized as a configuration of three continuums. Each CSR principle continuum represents a spectrum of executive interpretations. To illustrate the range, three focal points will be identified for each spectrum to define the key distinctions across perspectives.

Taken together, the CSR decision frame needs to define cognitive content (paradigm neutral fundamentals concerning CSR) and cognitive structure (mapping the relationships holistically). Following this content–structure principle, in the following section, we will further articulate the three pillars of a CSR decision frame and the underlying assumptions of the model.

2.3. Three Pillars of CSR Decision Frame

2.3.1. C Pillar: Corporate Purpose

The first pillar in a CSR decision frame is the principle of corporate purpose. It poses the question of what constitutes appropriate objectives for a corporation. Goal attainment is one of the defining characteristics of an organization [

57]. This question matters because it defines the nature of the relationship between a corporation and society and the role a firm plays in society, especially in terms of what types of values firms will deliver [

18]. However, this is also a long-debated issue in both academia and practice. Ultimately, how executives interpret this question sets the path for how they carry out leadership duties, including decisions concerning CSR [

58]. Thus, the C pillar is the most essential basis for the CSR decision frame, which is the pivotal point differentiating executives’ strategic thinking. To articulate the range of perspectives on the C pillar, we draw from current conversations about corporate objectives as the central-actor-role of a firm and identify three focal points: corporation as an economic actor, strategic actor, and social actor [

19,

38] (

Figure 2A).

The idea that a corporation plays the role of an economic actor occupies one end of the spectrum. It has its root in the classic economic paradigm that considers financial-wealth value creation as the sole purpose of the firm [

59,

60]. Within this paradigm, a corporation is a nexus of contracts determined by laws and regulations [

57]; and participates in society as an independent member making contributions by providing products, services, and financial wealth to the members of society while obeying its laws and regulations [

54,

61]. In short, this end of the spectrum represents the single-objective view that sees corporations and other members of society as having a clear separation of roles [

59,

62]. Businesses should focus exclusively on efficiently creating economic value. –The next perspective is the strategic-actor view, which is rooted in Porter and Kramer’s (2006) shared-value-creation argument [

15]. A corporation is still fundamentally seen as an economic actor, with wealth creation as its primary objective. However, firms are considered to have an interactive relationship with a number of core stakeholders, as opposed to being independent of other entities. Specifically, these key stakeholders have strategic impacts on a firm’s pursuit of economic goals [

63]. By addressing the interests and demands of these strategic stakeholders, companies can achieve legitimacy and reduce risk, thus making sustainable economic gains. Instead of a single economic objective, a business can pursue dual-central roles as an economic actor that is also chasing competitive power among other players by engaging in instrumental stakeholder strategies. Ultimately, the instrument orientation of the firm objectives, while recognizing the interactive nature of the relationship with primary stakeholders, still serves the economic purpose of the corporation [

64].

At the top of the C spectrum is the social-actor view of corporate objective rooted in the stakeholder paradigm [

13,

65]. A corporation is believed to be an integrative social actor that plays a function role to create synergistic value and improve overall social wellbeing [

18]. A business cannot be separated from the other members of society and has an interdependent relation with its stakeholders, defined as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives” [

66] (p. 46). There is an implicit social contract between the firm and society, and both stakeholders and society membershave expectations of the firm doing social good [

14]. An organization’s objectives of making contributions to society include delivering economic value and social and environmental benefits simultaneously [

67,

68].

2.3.2. S Pillar: Corporate Stakeholders

The S pillar in the decision frame (

Figure 2B) is the principle of stakeholder scope and asks who matters to the firm [

22]. This question helps define the boundaries of a business in the sense that it separates those who have legitimate interest and stake a claim to the firm (i.e., stakeholders) from those who are outside actors [

69]. Thus, the answer to this question determines the scope of executive attention and reveals how leaders assess the degree of stakeholder inclusion in strategic decision-making [

38]. To articulate diverging views on the boundaries of corporation and stakeholder scope, we identify three focal points along the stakeholder spectrum representing current dominant perspectives: shareholder primacy, strategic stakeholders, and integrative stakeholders.

Similar to the C pillar, one end of the stakeholder spectrum is a

shareholder primacy view rooted in economic-based firm theories [

59]. The defining doctrine in this perspective is that a firm’s responsibility starts and ends with the organization. Due to their economic stakes in the firm, shareholders are the sole stakeholders who have legitimate claims on the decisions of the firm [

70]. Miska et al. (2014) characterized the stakeholder scope at this focal point as a low degree of stakeholder inclusion [

38]. Although low stakeholder engagement is generally considered as none-zero, the law requires a minimum level of social performance. As such, other stakeholders are considered to make competing demands on the firm’s economic goal and, thus, represent either a derivative of the responsibility to shareholders or a conflict of interest [

3].

Moving upward along the S continuum, we highlight the perspective of the

strategic stakeholders of a firm [

13]. Being broader than the shareholder primacy view, this paradigm selects a more targeted group of constituents to prioritize over other interest groups. The selection criteria are normally based on the potential contributions of the stakeholder group to a firm’s economic bottom line and strategic competitiveness [

71]. Stakeholders are perceived as different in terms of stakeholder salience (the degree of stakeholder claim priority given by the decision-makers) [

13]. A salient stakeholder has legitimate claim on an executive’s decision [

53]. Logically, this selected group of stakeholders is considered the core stakeholders who have strategic value to a firm’s economic wealth generation [

72,

73]. In the end, this perspective presents a narrower scope of stakeholder inclusion in comparison with the extended stakeholder view.

The focal point of the

integrative stakeholder view underlines the obligation to address the interests and demands of a wide range of constituencies in firms’ strategic decision making, such as consumers, investors, suppliers, employees, and community members [

3,

38,

74]. In line with stakeholder theories, this view emerges from the principle that the demands and needs of each constituent should be considered and balanced in a firm’s decision-making processes [

75,

76]. Shareholders are a company’s stakeholders and creating values for stakeholders is inherently a pro-shareholder act.

2.3.3. R Pillar: Responsibilities of Leader

The third pillar in the CSR decision frame, R pillar (

Figure 2C), focuses on executive leaders’ responsibility of executives and asks questions about what constitutes strategic leaders’ responsibility and accountability and how to be a responsible leader. Responsibility is “the state of duty, accountability, and opportunity for action for an issue” [

77] (p. 300). It is no surprise that there is little consensus on what constitutes a firm’s executives’ responsibility [

78]. Responsible leadership is not the same concept for everyone [

54]. Such complexity arises because of variations in how executives interpret and define their roles, the parameters of leadership responsibilities, and accountability of performance outcomes. Like in the C and S pillars, in the R pillar, diverse views on leading responsibly can be mapped along an economic–social responsibility spectrum (

Figure 2C). Drawing from dominant theoretical foundations, we identify three focal points to illustrate the diverse understanding regarding the duties expected of leaders and the respective performance focus: economic responsibility, strategic responsibility, and social responsibility [

38].

On one end of the continuum is the classic

economic responsibility argument that depicts corporate leaders as agents for the principals (owners/shareholders) who are responsible for making the business profitable and delivering supreme financial returns while acting within the boundaries of regulations and laws [

59,

79]. By definition, the accountability of executives begins and ends with the boundary of the organization [

38,

54]. Thus, leaders’ core function is considered to be separating economic objectives from social objectives, and the only social responsibility for a corporation is to maximize profit [

60]. The ultimate criterion for evaluating the performance of the firm and leadership effectiveness is shareholder value. Consequentially, a leader’s performance focus depends on the firm “doing well” in efficiency (controlling and reducing cost associated with all corporate activities), profit and wealth maximization, and financial superiority [

59,

60,

76,

80].

Further upward along the leader-responsibility continuum is the

strategic-responsibility view or the converging view between economic and stakeholder responsibility [

38]. The parameters of leader accountability are different in the sense that many consider leaders as agents of the corporations (in contrast to shareholders). While chasing wealth creation and profit maximization, executives’ performance focus also expands to achieving a long-term competitive advantage and sustainable growth and value creation [

16]. Driven by such strategic responsibility, executives tend to recognize and explore the business case of serving the needs of certain groups of stakeholders, which can bring legitimacy, reputation, and other risk-management benefits for the company [

81,

82]. Thus, the performance orientation for these executives is having a competitive advantage and sustaining shared value generation, doing well by doing good [

26,

63,

64]. To realize the instrumental value of strategic stakeholder engagement, the effectiveness of responsible leaders within this paradigm is measured by how well executives can identify strategic stakeholders, balance trade-offs of competing interests, and align society-serving activities with a firm’s core competencies [

15,

71].

Further upward on the responsibility spectrum is the integrative stakeholder perspective, a

social responsibility or stakeholder responsibility view of responsible leadership. As articulated by the current writings on stakeholder and responsible leadership theories [

37,

74], this perspective has the most expanded scope of responsibility and degree of stakeholder inclusion [

38]. Specifically, executives recognize the interconnection among diverse stakeholders and the complexity and interdependence between business and society. Further, as the “agent of the world-benefit” and steward of the environment, they understand their duties and accountability toward sustainable development in economic, social, and environmental domains [

83] (p. 60). To lead responsibly is to do right by all stakeholders to achieve a triple bottom line (profit, people, and planet) [

84]. Thus, the responsible performance focus is on achieving sustainable and socially optimal outcomes through cooperative and collaborative stakeholder engagement and social innovation [

21,

26].

2.4. CSR Decision-Frame Assumptions

Now that we have articulated the three pillars in executives’ CSR decision frame, it is important to clarify four key assumptions of the conceptualization. As discussed earlier about the defining characteristics of decision frame, it is essential to have a cognitive structure that meets the requirements for both differentiation and integration.

Thus, the first assumption is that each of the three pillars represents a distinct principle concerning CSR, although all three are interconnected. Current writings in the CSR literature tend to articulate these three essential issues under one global assumption underpinning various paradigms of interest. Such a coarse-grained approach serves well a paradigm-level investigation. As the motive of this paper is to better understand the mechanisms explaining diverse CSR initiatives and, particularly, the role of decision-makers’ interpretations of essential issues, it is valuable to focus on nuanced and multifaceted ideological orientations. By conceptually differentiating corporate purposes, corporate stakeholder scope, and leadership responsibility, we can potentially explore more fine-tuned configurations both within and across pillars. Each pillar by itself is insufficient to capture the complexity of CSR issues. It is also possible that not all three pillars are equally salient for each decision-making episode. Teasing out the specific issues of decision-makers’ focus can be fruitful. Additionally, we expect that the three-pillar approach makes it feasible to develop a measurement scale for future empirical investigation. This leads to our second assumption. We contend that, within each pillar continuum, the focal points identified are not intended to indicate any clean typology. They serve as illustration points for the key characteristics of each respective central issue. Thus, differences among perceptions (points) that reside along the spectrum are more in terms of degree than pure categories; that is, they represent different shades of CSR decision logic.

The third assumption has to do with the reverse-shaped pyramid of each continuum. From bottom to top, the expanding shape captures the progression in the scope and breadth related to the essential meaning of each pillar. Based on the current literature, each upward stage indicates an additive and cumulative effect [

38,

55,

85,

86]. For instance, a strategic economic actor is an expansion to being an economic actor. Additionally, it signals a dynamic pathway. The place where an executive’s beliefs and interpretations might reside is not static. Rather, the progression might represent the growth phases and trajectory or the stages of a leader and the company they lead [

9]. The reverse is also true in the sense that leaders can regress along any particular pillar. The fourth assumption is about the integration property of the

cognitive structure. An executive’s CSR decision frame is ultimately a configuration of three pillars (

Table 2). This is the advantage of a decision frame over a paradigm conceptualization in terms of depicting nuanced and multifaceted mental models of executives. With a paradigm approach as in the current paper (

Table 2), the configuration is a perfectly aligned across C, S, and R pillars based on dominant theoretical perspectives. In contrast, taking a decision-frame lens, an executive can score a point anywhere along each of the three continuums (within or across paradigms), resulting in a within- or across-paradigm configuration.

2.5. Exemplar CSR Decision-Frame Configurations and Strategic Orientations

To illustrate the utility of the CSR decision frame in predicting CSR strategic orientation, we will discuss three paradigm-aligned configurations.

In

Table 2,

Configuration 1 depicts an executive’s CSR decision frame that has a strong economic orientation. In the eyes of the leader who sees the firm as an economic actor (C pillar), the primary objective for the firm is economic-wealth creation. This very purpose defines what the corporation is: an independent social entity that carries out its own duty as every other member of society should. Thus, any activity that is not related to its financial goals is not seen as valuable to the firm. As Milton Friedman argued, the only social responsibility of business is “to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game” [

60] (p. 6). Thus, CSR will be considered as other members’ obligation and will be avoided. When an executive addresses the essential question about who matters to the firm (S pillar) by exclusively identifying shareholders, then the boundary of the business is set. Any other claims (needs and demands) on a firm’s decisions will not be considered legitimate and will, thus, be ignored. Further, an orientation towards the economic responsibility of leadership (R pillar) generally signals a leader’s interpretation of their duties and accountabilities in the domain of the financial bottom line. Leadership effectiveness is measured by profit maximization for shareholders. Thus, investment in CSR will be a cost to be avoided unless the laws and regulations require it. A close look at how each of the three essential questions is addressed tells a coherent story about the theme of an economic paradigm of CSR. Based on this configuration of the CSR decision frame, we predict that the executive will likely focus their managerial attention exclusively on the economic aspects of the business, while keeping their CSR engagement to the minimum or choosing a compliance-oriented CSR strategy.

Configuration 2 tells a different story. The interpretation of corporate purpose (C-pillar) remains focused on economic value creation but with an expanded horizon. Leaders look beyond the short-term shareholder value and focus on long-term, sustained economic success. Interaction and interconnectedness among social entities are recognized on the managerial radar. Instead of separation of goals, a “business case” can be made to recognize the value of serving the interests of others, or at least a particular group of “others”. In this configuration, CSR is defined in terms of its value toward the competitive advantage of the firm (e.g., legitimacy, reputation, risk management). Firms engage in CSR initiatives selectively when it is strategically meaningful to the bottom line and gives them a competitive advantage, that is, strategic CSR. Next, when a leader expands the boundaries of a firm to grant legitimacy to the primary stakeholders (S pillar), CSR concerning these stakeholders is likely to become a part of the strategic plan. However, a firm might identify different stakeholder groups to prioritize based on their strategic implications at various times. Consequently, CSR is a responsive strategy for sustaining a competitive advantage. A leader’s orientation towards strategic responsibility (R pillar) focuses on achieving a sustainable competitive advantage through the means of doing well by doing good. More specifically, doing “strategic” good points to the likelihood of the adoption of strategic CSR by the executive.

Finally, Configuration 3 presents the most expansive decision frame. Leaders see the role of a business as a corporate citizen and social actor who is an integral part of society (C pillar), with an interdependent relationship between business and society. The purpose of a firm is not purely economic or strategic, but insteadthe firm is expected to make direct contributions to the welfare of society. Firms purposefully create strategic initiatives to provide for the social good. Therefore, CSR is a natural and imperative part of strategic planning and execution. CSR concerns are embedded within the core business strategy. Regarding the question of who matters for the firm (S pillar), “Each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to delivery values to all of them”. When a leader thinks using a stakeholder-focused lens, the decision focus shifts to balancing and aligning diverse demands and promoting cooperation and collaboration among stakeholders, which leads to integrative CSR. A social-responsibility orientation of leadership (R pillar) defines doing the right thing and leading responsibly as achieving sustainability in economic, social, and environmental domains simultaneously. As mentioned before, Nooyi famously stated that the responsible strategy should be “performance with purpose and to root PepsiCo’s contribution to the society in its core business model”.

3. Discussion and Future Research Agenda

There are a wide range of corporate responses to social and environmental issues. Accumulated research on CSR has advanced the understanding of the phenomenon with multiple prominent conceptual paradigms. However, much less attention has been given to the CSR decision makers and the impact of their cognitive framing related to CSR. As a result, we have not been able to provide an encompassing framework to articulate and organize widely diverse managerial interpretations of CSR issues. The main objective of this paper is to develop a CSR-specific decision frame to understand how corporate executives process information and make decisions concerning CSR in different fashions. We develop the framework by bridging two main areas of literature in the field, macro- and micro-focused research, using a managerial cognition lens. Specifically, we identify three key principal assumptions underlying extant CSR paradigms and build a managerial mental model containing three sets of core questions concerning CSR: What is the corporation’s purpose (C)? Who matters to the corporation (S)? And what are leadership responsibilities (R)?

The theoretical contributions of a CSR decision-frame approach are twofold. First, a dimensional CSR decision frame complements and expands from existing paradigm views of CSR heterogeneity. Further, instead of a debate perspective on diverse CSR paradigms, we adopt a synthesizing approach to map these paradigms along three continuums to reflect the complex reality of diverging-while-coexisting CSR ideologies adopted by corporate executives. The configuration of three continuums (C, S, and R) provides a fine-grained framework to capture more nuanced diversity in executives’ interpretations of social and environmental issues. Second, we provide a process lens to link the drivers of CSR with CSR strategy by unpacking the black box of strategic information processing and decision making. As depicted by UET, CSR can be considered a pathway flow from macro and micro drivers to strategic choices and performance outcomes (

Figure 1) [

28,

29]. However, the process has yet to be connected with the under-researched information filtering process within a decision-making framework. The three-pillar CSR decision-frame model provides an explanatory mechanism that connects diverse drivers with differing strategic modes coherently.

As our focus is on articulating the content and structure of a managerial CSR decision frame, there are a couple of resulting limitations we need to acknowledge. The conceptualization of the three continuums (C, S, and R) provides an encompassing bandwidth, allowing nuanced and multifaceted configurations both within and across paradigms. However, for the purpose of simplicity, we take a broad perspective and illustrate the utility of a CSR decision frame with three paradigm-aligned configurations. We do consider that this is an area with potential. In future research, development of a three-dimensional scale to operationalize the CSR decision frame will be fruitful. That will open the doors to testing the relationships between fine-grained decision-frame configurations and diverse CSR orientations. Another limitation of this paper is that we did not articulate the conceptual relationships between the micro and macro drivers of CSR with the decision frame. Future researchers can further explore how executives’ diverse psychological orientations might predict varying CSR decision frames and resulting CSR strategic orientations.

We also believe that this CSR decision-frame lens has practical implications. The CSR decision-frame approach has made explicit essential assumptions about CSR using an organized structure. Consequently, the CSR decision frame can be a useful tool to help managers organize, articulate, and communicate their strategic process both within the firm and with public stakeholders. Similarly, social and environmental issues have often been at the center of heated debates in both the business world and the broader social arenas. By acknowledging the underlying assumptions about using a CSR decision frame, conversations, particularly those between different ideological stances, can be brought on the same page and within the same bandwidth.