The Procurement Agenda for the Transition to a Circular Economy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

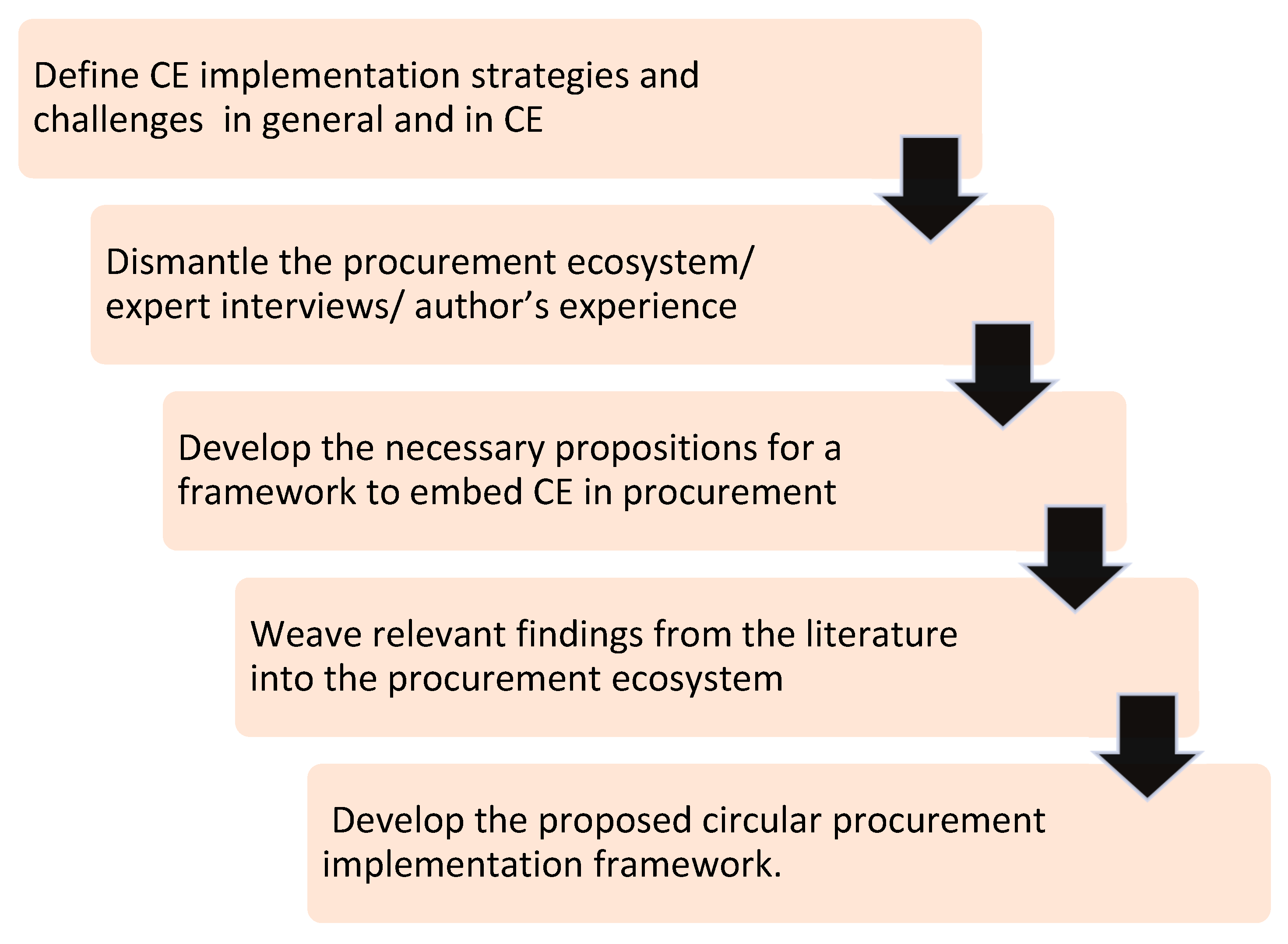

2. Methodology

3. Circular Procurement

3.1. Circular Economy

- Circular Supply Models. This model considers that materials of products do not eventually become waste. This model is often referred to as the “cradle to cradle” product design;

- Resource Recovery Model. This involves the production of secondary raw materials from the waste stream. It covers three forms: 1. downcycling, where lower-value materials or products compared with the source are generated; 2. upcycling, where a higher-value material or product, compared with its source, is generated; 3. industrial symbiosis, which is the direct circulation of waste streams from one firm into the production process of another;

- Product Life Extension Model. This model involves extending the useful life of products through repair, refurbishment, or remanufacturing. This requires manufacturers to adopt product-design strategies that enable such interventions through the design of the product for increased ease of repair and disassembly;

- Sharing Model (Sharing Economy). This involves using under-utilized consumer assets more intensively through either lending or pooling. One sharing model is co-ownership, which involves the lending of physical goods, and co-access, which involves allowing others to take part in an activity that would have taken place anyway, such as carpooling;

- Product Service Model. This model combines a product with a service, and it is known as the servitized business model. There are three variants for this model: 1. product-oriented product service systems where after-sale services are provided through repair offerings, extended product warranties, or take-back agreements; 2. user-oriented product service systems that involve providing access to the services associated with a particular good without having ownership of the good itself; 3. result-oriented product service systems where, instead of selling goods or assets, the services or outcomes provided by these goods are sold.

3.2. Circular Procurement

3.2.1. Circular Procurement Strategies

- Promoting circular supply chains by procuring more circular products, materials, and services;

- Promoting new business models based on innovative and resource-efficient solutions.

- Meet specified resource efficiency levels on a whole lifecycle basis;

- Include recycled content;

- Incorporate the potential for reparability;

- Limit/eliminate the use of hazardous chemicals and ensure the nontoxicity of components;

- Reuse: if the lifetime of a product exceeds its contract term, it could be shared or sold;

- Repair/refurbish: refurbishing or repairing could be an option in the tender specification;

- Remanufacturing: At the end of the contract, products can be dismantled and renewed, and some of their components can be remanufactured;

- Recycle: materials can be extracted by components of a product for recycling.

- Product–Service System (PSS): customers do not demand products but seek the utility that is provided by products and services. PSS integrates products and services to deliver value rather than resources [37]. For example, instead of buying a printer, the customer buys printing services by leasing or renting the printer. This could decouple economic growth from consumption;

- Supplier take-back systems: this could be in the form of a “purchase and buy back” or “purchase and resale” agreement. It encourages refurbishment and remanufacturing or a third-party purchase of the product from the user and gives the product a second life;

- Sharing platforms/collaborative consumption and sharing economy services: optimizing the use of underused assets via shared use. Simplified access can consequently lower demand for new products.

- Strengthening and adapting consumer information tools: consumer product information should include the product’s durability, reparability, availability of spare parts, material recyclability, components, and the possibilities for reuse and remanufacture;

- Lifecycle costing and total cost of ownership methods: usually, lifecycle costing and total cost of ownership shows the preference for products or services that rely on fewer resources or maintenance in term of cost-effectiveness;

- Cooperating with other organizations: partnerships to pool products and service providers to set up sharing and reusing systems;

- Knowledge and information management systems: sharing experiences and initiatives can help in the adoption of circular solutions;

- Legal instruments: formalizing policy that addresses circularity in the procurement process is critical;

- Fiscal instruments: fiscal incentives should be provided to public procurement agencies since products and services that promote circular systems may have higher upfront costs than traditional ones.

3.2.2. Challenges Adopting Circular Procurement

- Provide suppliers with the opportunity to offer their circularity contribution without having to be the original equipment manufacturer (OEM). This could be in a proposal to reuse or disassemble the product after its lifecycle, which could later influence OEM;

- Establish standard cruciality metrics for certain products and services.

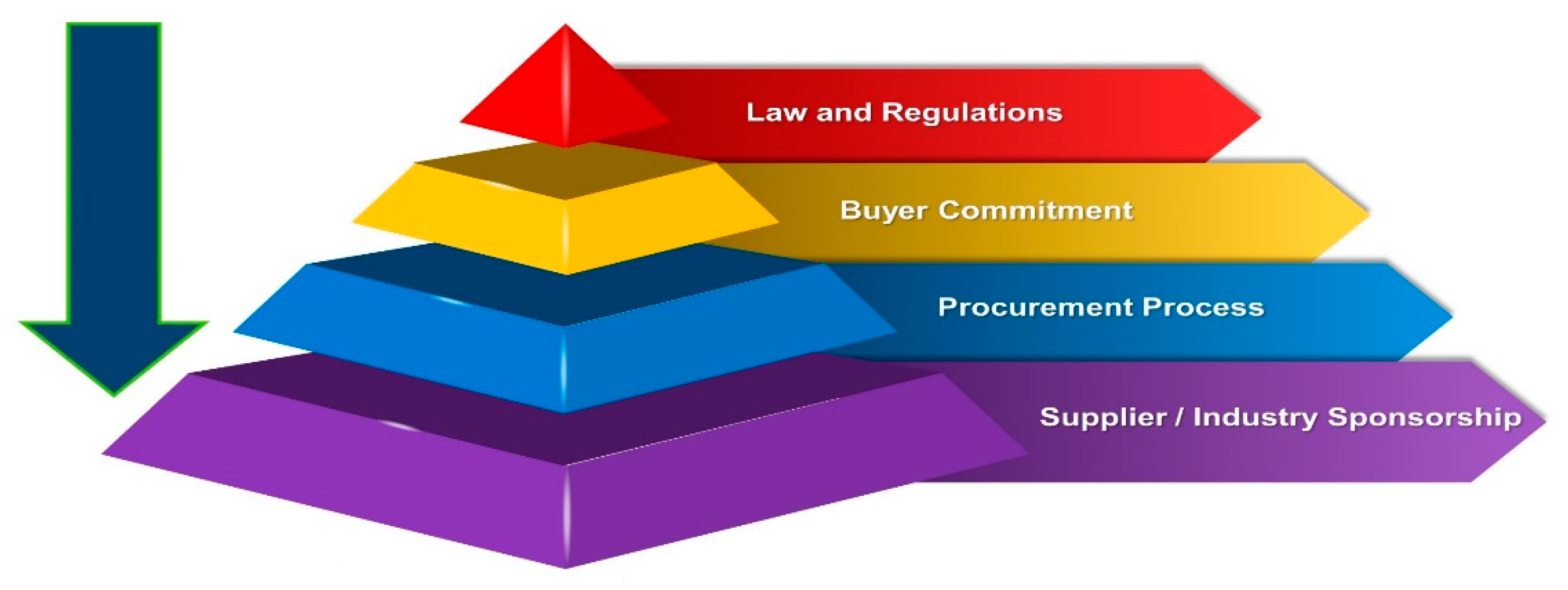

4. Procurement Ecosystem

4.1. Procurement Process Lifecycle

4.1.1. Pre Bidding

4.1.2. Bidding

4.1.3. Post Bidding

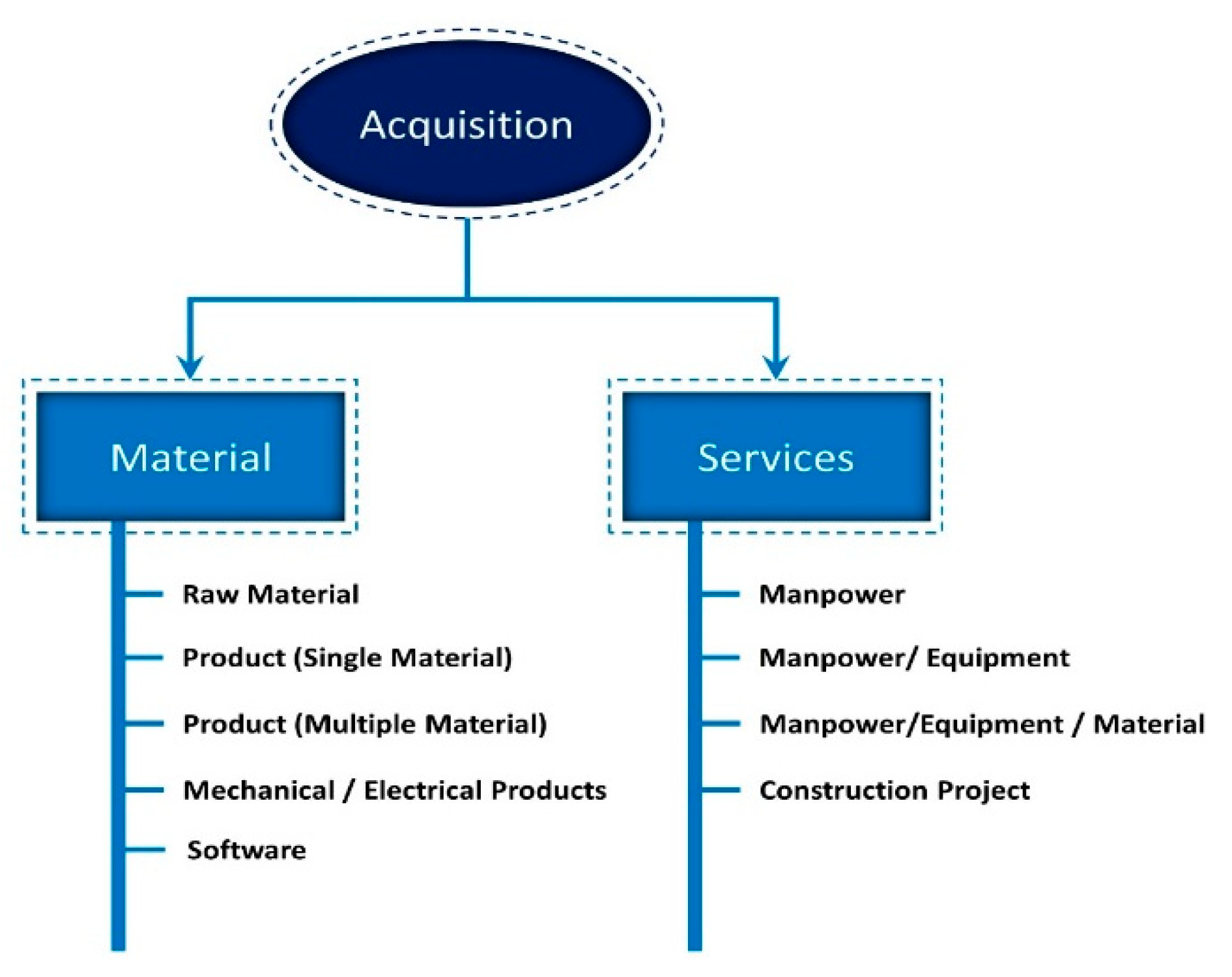

4.2. Procurement Procedures

5. Circular Procurement Implementation Framework

- The CE procurement business environment;

- CE buyers;

- Procurement process enablers;

- Professional practitioners;

- Policies and procedures;

- IT solutions;

- Procurement process activities;

- Supplier prequalification;

- Technical evaluation;

- Award evaluation;

- Post awards;

- Suppliers.

5.1. CE Procurement Business Environment

5.2. CE Buyer

5.3. CE Procurement Process Enablers

5.3.1. Professional Practitioners

5.3.2. Policies and Procedures

5.3.3. IT Solution

5.4. Procurement Process Activities

5.4.1. Supplier Prequalification

5.4.2. Technical Evaluation

5.4.3. Award Evaluation

5.5. Post Award

5.6. Supplier

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- Governments can play an important role in promulgating laws and regulations that encourage CE within public procurement and the industry via various schemes;

- Buyers should be willing to pay a potential premium for circular products or services. Governments, as public buyers, should allow for such premiums as investments that will yield returns in the long run for the benefit of society and global sustainability;

- Professional practitioners should be acquainted with CE principles through training to address CE in drafting the agreement pro forma and during the technical and proposal evaluation;

- General governing principles should be established to assist procurement professionals to include CE. These principles should provide guidelines on how to select the appropriate CE strategies for each acquisition;

- The Material Master Data-Management system could be used to retain CE requirements at the product level;

- Certification of products and services’ circularity by a third party (e.g., an association) is essential for circular procurement;

- A certain weight in the bidders’ prequalification evaluation should be assigned to the adoption of CE within the supplier’s business model;

- The CE proposal should demonstrate the circularity of the deliverables, per the nature of the procurement. While the focus in material acquisition should be on the product, in services, the focus should be on the business model;

- For construction projects, a standalone CE proposal and evaluation based on lifecycle assessment (LCA) could be requested from bidders in a manner akin to a value-engineering proposal;

- The bid–award system should give preferential treatment to circular materials or services. This could incur additional costs. The organization should establish a cap for the acceptable premium to prevent any abuse by suppliers;

- Buyers should ensure that suppliers comply with the circular requirements;

- Communication between suppliers and buyers is important to establish a CE supplier base, especially when there is a monopoly market and the supplier has a better edge than the buyer.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Industrial Development Organization. Circular Economy. Available online: Circular_Economy_UNIDO_0_.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Hazen, B.T.; Russo, I.; Confente, I.; Pellathy, D. Supply chain management for circular economy: Conceptual framework and research agenda. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogzaad, J.A.; Lembachar, Y.; Bąkowska, O.; Pascual, J.; Verstraeten-Jochemsen, J.; de Wit, M.; Morgenroth, N. Climate change mitigation through the circular economy—A report for the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel (STAP), to the Global Environment Facility (GEF): Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2020. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/climate_change_mitigation_through_the_circular_economy_circle_economy_2021.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Australian Government. Sustainable Procurement Guide, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Canberra, November. CC BY 4.0. 2021. Available online: https://www.agriculture.gov.au/ (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Bressanelli, G.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Challenges in supply chain redesign for the circular economy: A literature review and a multiple case study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7395–7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Towards ecological management: Identifying barriers and opportunities in transition from linear to circular economy. Philos. Manag. 2019, 20, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Miguel, M.; van Langen, S.K.; Ncube, A.; Zucaro, A.; Fiorentino, G.; Passaro, R.; Santagata, R.; Coleman, N.; Lowe, B.; et al. Circular Economy and the Transition to a Sustainable Society: Integrated Assessment Methods for a New Paradigm. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2021, 1, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.H. Circular Economy and Public Procurement: Dialogues, Paradoxes and Innovation. Ph.D. Dissertation, Technical Faculty of IT and Design. Aalborg University:, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.; Sohn, I.K.; Bendsen, A.L. Circular Procurement best Practice Report. SPP Regions (Sustainable Public Procurement Regions) Project Consortium. 2017. Available online: https://sppregions.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Resources/Circular_Procurement_Best_Practice_Report.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Building Circularity into our Economies through Sustainable Procurement. 2018. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/26599/circularity_procurement.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Arvidsson, S.; Dumay, J. Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Nancy Bocken, M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The circular economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witjes, S.; Lozano, R. Towards a more circular economy: Proposing a framework linking sustainable public procurement and sustainable business models. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 112, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Public Procurement for a Circular Economy. Good Practice and Guidance. 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/pdf/Public_procurement_circular_economy_brochure.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Pollice, F.; Batocchio, A. The new role of Procurement in a circular economy system. In Proceedings of the 22nd Cambridge International Manufacturing Symposium, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 27–28 September 2018; Available online: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/284340/2_-_the_new_role_of_procurement_in_a_circular_economy_system_pollice_batocchio.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Khan, S.; Haleem, A.; Khan, M.I. A grey-based framework for circular supply chain management: A forward step towards sustainability. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, C.; Jones, M.; Montevecchhi, F.; Neubauer, C.; Schreiber, H.; Tisch, A.; Walter, B. Green public procurement and the EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy. In Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, IP/A/ENVI/2016. 16 June 2017. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/602065/IPOL_STU(2017)602065_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Nordic Council of Ministers. Circular Public Procurement in the Nordic Countries. 2017. Available online: https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1092366/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Giné, L.F.; Vanacore, E.; Hunka, A.D. Public procurement for the circular economy: A comparative study of Sweden and Spain. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; Towards a Circular Economy: A Zero Waste Programme for Europe. Document 52014DC0398. 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52014DC0398 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Al-Sinan, M.A.; Bubshait, A.A. Using plastic sand as a construction material toward a circular economy: A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. 2013. Available online: https://www.werktrends.nl/app/uploads/2015/06/Rapport_McKinsey-Towards_A_Circular_Economy.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Jones, N.; Stefanakis, A. Circular economy and sustainability: The past, the present and the future direction. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira-Streit, J.A.; Endo, G.Y.; Guarnieri, P.; Batista, L. Sustainable supply chain management in the route for a circular economy: An integrative literature review. Logistics 2021, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, J.M.; Avilés-Palacios, C. Circular economy as a catalyst for progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals: A positive relationship between two self-sufficient variables. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.E.; Batlles de la Fuente, A.; Cortés-García, F.J.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J. Theoretical research on circular economy and sustainability trade-offs and synergies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development United Nations Organization. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development?utm_source=EN&utm_medium=GSR&utm_content=US_UNDP_PaidSearch_Brand_English&utm_campaign=CENTRAL&c_src=CENTRAL&c_src2=GSR&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIoJOX2LbG-QIVT41oCR2QUg1wEAAYAiAAEgJ6f_D_BwE (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Velenturf, A.P.M.; Purnell, P. Principles for a sustainable circular economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1437–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 20400:2017; Sustainable Procurement—Guidance. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- BSI 8001; Developing BS 8001—A World First. 2017. Available online: https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/standards/benefits-of-using-standards/becoming-more-sustainable-with-standards/BS8001-Circular-Economy/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Pauliuk, S. Critical appraisal of the circular economy standard BS 8001:2017 and a dashboard of quantitative system indicators for its implementation in organizations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.; Rammel, C. Decoupling: A key fantasy of the post-2015 sustainable development agenda. Globalizations 2017, 14, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hina, M.; Chauhan, C.; Kaur, P.; Kraus, S.; Dhir, A. Drivers and barriers of circular economy business models: Where we are now, and where we are heading. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 333, 130049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaharia, P. Circular economy: The beauty of circularity in value chain. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 1, 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Business Models for the Circular Economy: Opportunities and Challenges for Policy; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, A.Z.; Aurisicchio, M. A framework to use product-service systems as plans to produce closed-loop resource flows. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 252, 119733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanacore, E.; Williander, M. Public Procurement with a Circular Economy (Edge). Project submitted to RISE Research Institutes of Sweden AB, A Vinnova-Funded Project—Ref. 2018-04696. Available online: https://www.ri.se/sites/default/files/2020-03/PROCEED%20-%20FINAL%20REPORT_0.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S.; Mishra, N. Barriers to effective circular supply chain management in a developing country context. Prod. Plan. Control. 2018, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KakweziI, P.; Nyeko, S. Procurement processes and performance: Efficiency and effectiveness of the procurement function. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Manag. Entrep. 2019, 3, 172–182. Available online: http://mail.sagepublishers.com/index.php/ijssme/article/view/42 (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- United Nations. Procurement Manual, Department of Operational Support Office of Supply Chain Management, Procurement Division. Ref No: DOS/2020.09. Available online: https://www.un.org/Depts/ptd/sites/www.un.org.Depts.ptd/files/files/attachment/page/pdf/pm.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- OECD. Principles for Integrity in Public Procurement; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/48994520.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Barriers | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Internal Barriers: | |

| 1.1 | Company policies and strategies | The absence of clear policies and approaches addressing CE restricts organizations from effectively adopting CE. |

| 1.2 | Financial | Adopting CE entails investments in innovative technology, employee training, and production, which could be financially infeasible. |

| 1.3 | Technological | The inability of organizations to have access to or the capacity for technology necessary to adopt CE. |

| 1.4 | Lack of resources | Lack of time. |

| 1.5 | Collaboration | Organizations are reluctant to share information because of competition, which hinders effective collaboration among organizations. |

| 1.6 | Product design | Introducing CE principles in product design could be challenging. For instance, substituting materials with recycled alternatives could lower quality. |

| 1.7 | Internal stakeholders | Lack of communication among departments when identifying departmental responsibilities towards CE. |

| 2 | External Barriers | |

| 2.1 | Consumer | Durable product design increases prices and encourages consumers to purchase such products. Consumers might not be willing to purchase recycled or refurbished products. |

| 2.2 | Legislative and economic | Frequent changes in government policies and the absence of regulations affect the establishment of remanufacturing companies. |

| 2.3 | Supply chain | Supply chains suffer from a fragmentation problem, which may prevent the chain’s actors from knowing the activities of other actors. |

| 2.4 | Social, cultural, and environmental | Absence of people’s involvement (or social inclusion) in CE implementation. |

| No | Driver | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Internal Drivers | |

| 1.1 | Organizational | Leadership is considered to be the most critical element for the successful implementation of CE. |

| 1.2 | Resource availability and optimization | Knowledge and technological resources are important to embrace CE. |

| 1.3 | Financial factors | Reducing raw materials and producing remanufactured product revenues could encourage more investment in CE. |

| 1.4 | Product and process development | High-quality durable products and environmentally friendly products are appreciated by consumers. |

| 2 | External Drivers | |

| 2.1 | Policies and regulations | Governments, through their policies and regulations, could encourage consumers and businesses to implement CE via tax breaks, supporting funds, and subsidies. |

| 2.2 | Supply chain | Collaborations between supply chain partners could promote waste management |

| 2.3 | Society and environment | CE supports addressing environmental safety concerns and minimizing business operation risks. Addressing environmental concerns benefits society. |

| 2.4 | Stakeholder pressure | Pressure from key stakeholders could drive a company to adopt CE. |

| 2.5 | Infrastructure | Physical infrastructure, such as utilities, buildings, and roads, is assumed to be an essential component of CE implementation. |

| No. | Strategy | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reuse | When a product or its components have reached the end of their first use and are used for the same purpose for which they were conceived. |

| 2 | Repair | Fixing a fault in a product instead of replacing it. |

| 3 | Refurbish | Returning a product to good working condition by replacing major components and making changes to update its appearance. |

| 4 | Remanufacture | Returning a product or component to the performance specification of the original manufacturer. |

| 5 | Recycle | Reprocessing waste materials in a production process for their original purpose or for other purposes excluding energy recovery. |

| 6 | Reduce | Lowering resources used in and by the products from a lifecycle perspective. |

| 7 | Refuse | Preventing the use of raw materials. |

| 8 | Repurpose | Reusing a product for a different purpose. |

| 9 | Recover Energy | Incineration of residual flows. |

| 10 | Rethink | Rethinking the way products are produced. |

| No. | Category | Scope |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Production | Promoting product eco-design |

| Promoting waste management in the industrial sector | ||

| Promoting extended producers’ responsibilities | ||

| 2 | Consumption | Increasing repair services |

| Promoting waste prevention | ||

| Promoting sharing/reuse/refurbishment | ||

| 3 | Waste management | Contributing to long-term recycling targets |

| Monitoring of waste quantities | ||

| 4 | From waste to resources/recycled material | Improving/investing in waste management infrastructure |

| Improving the quality of standards for secondary raw material | ||

| Information flow on secondary materials | ||

| Reducing the presence of hazardous substances in purchased products and services |

| No. | Enabler | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Environmental awareness and education | The organization should spread environmental awareness. |

| 2 | Design for longevity, reliability, and durability | The product should be designed to be durable and reliable. |

| 3 | Alignment of CE goals with strategic objectives | The organization’s strategic objectives should be aligned with CE. |

| 4 | Synergistic partnerships | Develop collaboration between product users and producers. |

| 5 | Economic pricing for used product | The remanufactured, refurbished, or second-life product has a lower price, which encourages consumers to purchase it. |

| 6 | Cascading and repurposing | Cascading focuses on the consecutive utilization of products or materials and resources throughout the lifecycle through repurposing. |

| 7 | Transparency within the supply chain | Supply chain partners should create transparency to implement CE practices across the supply chain. |

| 8 | Effective relationships with logistic partners and suppliers | An organization needs to establish a good relationship with supply chain partners, logistics providers, and suppliers to ensure the high performance of the CE supply chain. |

| 9 | Takeback management | Takeback management consists of deposit systems that can take back new products, used products, and waste materials in an effective manner. |

| 10 | Long-term planning | The organization should have a long-term vision and short-term plan regarding the adoption and benefits of CE. |

| 11 | Development of CE culture | Creating a robust CE culture through training for effective adoption and implementation of CE practices. |

| 12 | Effective performance measure system | Organizations should develop and incorporate effective performance and feedback measures both upstream and downstream of the supply chain. |

| No. | Barrier | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lack of industry incentives for green activities | Lack of financial support from government agencies to the industries. |

| 2 | Lack of environmental laws and regulations | Weakness or absence of laws and regulations that augment CE. |

| 3 | Lack of management commitment | Failure of management to demonstrate commitment to adopting CE. |

| 4 | Lack of preferential tax policies for promoting CE | Preferential loans and tax benefits for waste reduction could help promote circularity in supply chain concepts. |

| 5 | Lack of implementation of environmental management certifications and system | Environmental certificates could drive industries to be more proactive. |

| 6 | Lack of middle and lower-level managers’ support and involvement in promoting ‘green’ products | Middle and lower levels of management play important roles in executing the vision of top management with regard to CE implementation. |

| 7 | Lack of customer awareness and participation in circular supply chain activities | Unawareness of the circularity by the customer who decides purchasing preferences could hinder the acceptance of circular models in the supply chain. |

| 8 | Poor demand/acceptance for environmentally superior technologies | More advanced technology and upgraded equipment and facilities could accomplish circular initiatives in supply chains. |

| 9 | Lack of technology transfers | Adopting new technologies could improve CE in the supply chain. |

| 10 | Inadequacy in knowledge and awareness of organizational members about circular supply chain management initiatives | Inadequate knowledge and awareness of organization members in circular supply chain management hinders the promotion of circular products with higher reuse, recycling, remanufacture, and repair. |

| 11 | Lack of appropriate training and development programs for supply chain members | Skills and knowledge of circularity by the supply chain member are important to adopt a circular supply chain. |

| 12 | Lack of effective planning and management for circular concepts | Inadequacy in planning and management could mislead supply chain players from focusing on critical issues in circular supply chain adoption. |

| 13 | Lack of systematic information systems | The structure of the supply chain is very complex at the organizational level. There is a need to design and follow an information system network based on the system approach. |

| 14 | Lack of coordination and collaboration among supply chain members | Collaboration and coordination between suppliers and vendors are important since it is impossible for a business to have in-house arrangements for the reuse, recycling, and remanufacturing of all their by-products. |

| 15 | Lack of support and participation of stakeholders | Without active participation from stakeholders, it is difficult to implement any innovation in processes and technology or streamline the stakeholder’s efforts in circular supply chain management implementation. |

| 16 | Lack of economic benefits in the short-run | A lack of economic benefits in the short-run, such as increasing short-term costs, could hinder adopting a circular supply chain. |

| Item | CE Strategy | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Servitized business model |

|

| 2 | Prolonging product lifespan (durability) |

|

| 3 | Recycling | Product complexity in terms of materials contents. |

| 4 | Disassembling for remanufacturing | Customized products are designed for customers, which makes reuse or remanufacturing of the customized products more challenging. |

| 5 | CE regulations and incentives | Lack of policies and regulations that promote CE. |

| 6. | Renovation processes | Recycling could be very expensive compared with linear production from raw materials. |

| Acquisition Type | Strategy | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Raw material | Reduce | Sand, cement |

| Product with a single material | Recycle/refurbish/reuse | Pipe, pallets |

| Product with multiple materials (nonelectrical/nonmechanical) | Refurbish/Reuse/disassemble | Furniture |

| Mechanical/electrical products | Repair, prolonged lifecycle, remanufacture, lease | Turbine/power generator/pump |

| Workforce service | N/A | |

| Workforce/equipment | Shared services | Transportation |

| Manpower/equipment/product | Servitized business model Shared services | Printing services |

| Construction project | Lifecycle assessment |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Sinan, M.A.; Bubshait, A.A. The Procurement Agenda for the Transition to a Circular Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811528

Al-Sinan MA, Bubshait AA. The Procurement Agenda for the Transition to a Circular Economy. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811528

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Sinan, Mazen A., and Abdulaziz A. Bubshait. 2022. "The Procurement Agenda for the Transition to a Circular Economy" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811528

APA StyleAl-Sinan, M. A., & Bubshait, A. A. (2022). The Procurement Agenda for the Transition to a Circular Economy. Sustainability, 14(18), 11528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811528