Eliciting Brand Loyalty with Elements of Customer Experience: A Case Study on the Creative Life Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Experience Economy

2.2. Customer Experience and Brand Loyalty

2.3. Customer Experience and Creative Life Industry

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Sites

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

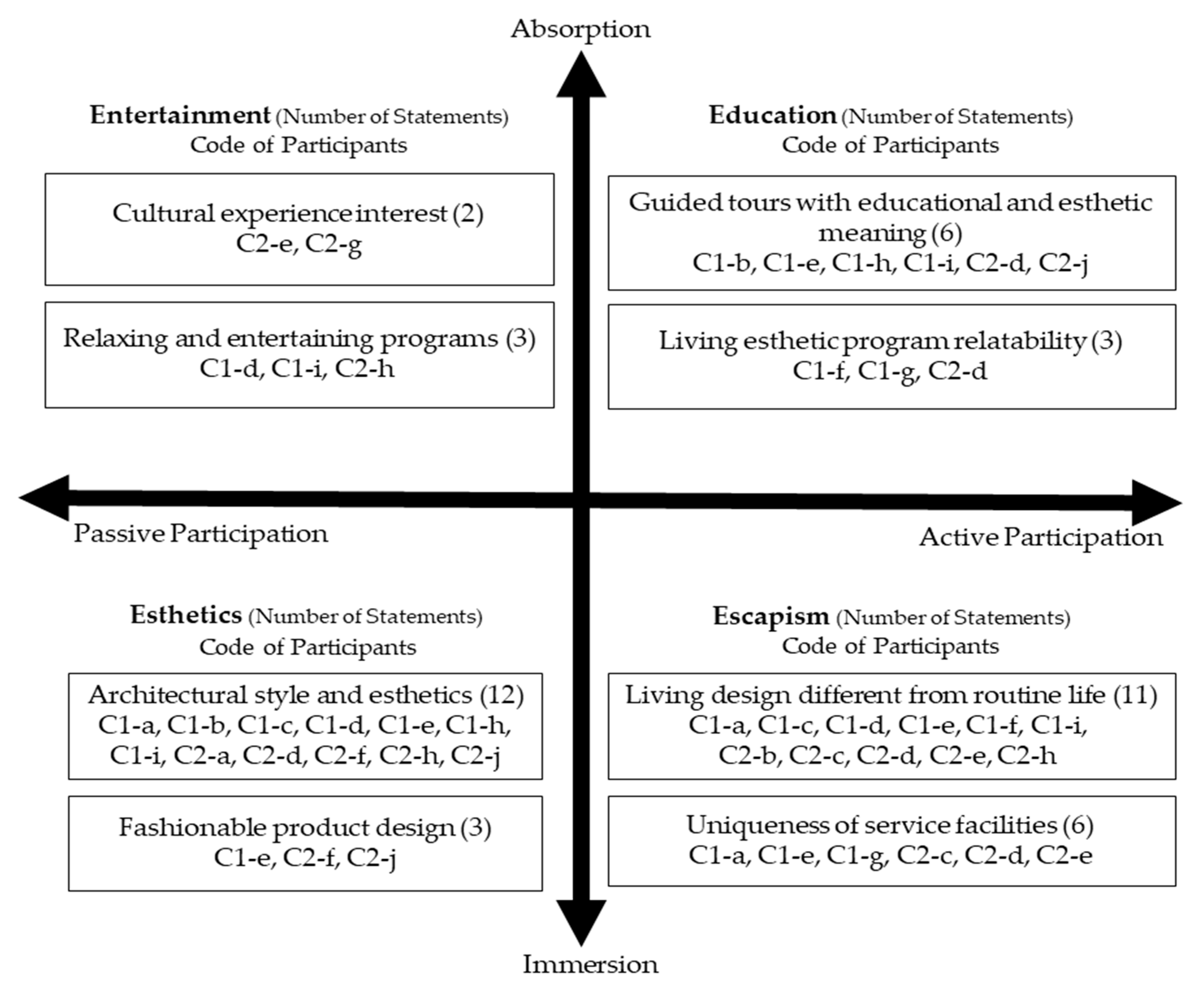

4.1. Realms of Experience

4.1.1. Entertainment Realm

4.1.2. Educational Realm

“The butler tour guide told us about the origins of certain joints and buildings [...], and we have learned a lot from it.”(C2-j)

“It was an educational experience, as I am eager to learn new things. There are [in the garden] a lot of vanilla plants, which I like a lot. And I also get [to know] several vanilla varieties—[the experience was] a lesson full of knowledge.”(C1-b)

“The guide did talk about some uses of vanilla”(C1-i)

“The vanilla extraction machine looks fabulous and it made the activity special”(C1-g)

4.1.3. Esthetic Realm

“The design of the room made me relax, where I can be alone without being bothered. Most importantly, the artwork inside and [the] outdoor spa gave me an impression of [an] extremely simple and natural esthetic design, which also helped me escape from the present [...] the room decoration was more like minimalism.”(C1-c)

“I [could sense] the strong esthetic style here, where the guide introduced each design element of the building”(C2-a)

“The tour began at 4:30 p.m. and ended around 5:30–6:00 p.m. when we were back. Because it was dark throughout the trip, we were each giv en a lantern. The scene when [everyone] was holding a lantern while walking was stunning; the vibe was great.”(C2-e)

4.1.4. Escapist Realm

“Our usual life is in a city with high walls. When we [are] there, we feel different from reality. [...] In daily life, we can’t experience such a garden living space”(C2-b)

“When you walk into this resort, it doesn’t look like a regular hotel, but rather like home. The location of the resort is quite hidden, and when you go in, it seems to be far away from the hustle and bustle of the city. [...] The hotel’s bathtub, swimming pool, and herb-related room facilities [...] can make you completely relax and experience a different living environment than routine life”(C1-a)

4.2. Customer Experience and Brand Loyalty in CLI Businesses

“I want to experience different styles of accommodation”(C2-b)

“Maybe I’m older and I don’t like to go to noisy places. The buildings in the park look very comfortable and when there are few people in the park, it is very comfortable to walk around”(C2-f)

“The yogic pavilion and the scenery of the larch pine in the garden [...] make people feel that the soul is united. Next time, I want to experience this program”(C1-c)

“I’m looking forward to experiencing a wedding at the Kengo Kuma’s Wind Eaves Pavilion, [which] was beautiful and [special]”(C2-c)

“When some cultural or festival programs [are] provided by The One Nanyuan, I will be interested in coming here to experience it again”.(C2-h)

“Next time, I hope to experience a concert at the Kengo Kuma’s Wind Eaves Pavilion—that will be a great pleasure”.(C2-c)

“Because I like minimalism and the facilities of the resort are beyond my imagination, I just think it’s really great and I will recommend it to my friends to stay”.(C1-c)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pine, B.J., II; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. In Harvard Business Review; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J., II; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Quadri-Felitti, D.L.; Fiore, A.M. Destination loyalty: Effects of wine tourists’ experiences, memories, and satisfaction on intentions. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 13, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeong, E.; Qu, K. Exploring Theme Park Visitors’ Experience on Satisfaction and Revisit Intention: A Utilization of Experience Economy Model. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 21, 474–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri-Felitti, D.; Fiore, A.M. Experience economy constructs as a framework for understanding wine tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, C.; Oh, E.J.; Jeong, C. A qualitative analysis of South Korean casino experiences: A perspective on the experience economy. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Ma, E.; La, L.; Xu, F.; Huang, L. Examining the Airbnb accommodation experience in Hangzhou through the lens of the Experience Economy Model. J. Vacat. Mark. 2021, 28, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, O.A.; Kesavan, R.; Bernacchi, M. Lasting customer loyalty: A total customer experience approach. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Witham, M. Dimensions of Cruisers’ Experiences, Satisfaction, and Intention to Recommend. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Hussain, K.; Ragavan, N.A. Memorable Customer Experience: Examining the Effects of Customers Experience on Memories and Loyalty in Malaysian Resort Hotels. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, M.; Holbrook, M.B. On the conceptual link between mass customisation and experiential consumption: An explosion of subjectivity. J. Consum. Behav. 2001, 1, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J., II; Gilmore, J.H. The experience economy: Past, present and future. In Handbook on the Experience Economy; Sundbo, J., Sørensen, F., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Gloucestershire, UK, 2013; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Crick-Furman, D.; Prentice, R. Modeling tourists’ multiple values. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring Experience Economy Concepts: Tourism Applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Chiu, Y.-T.; Wang, C.-H. The Visitors Behavioral Consequences of Experiential Marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 21, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. A study on the application of the experience economy to luxury cruise passengers. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Oh, H.; Park, J. Measuring the Experience Economy of Film Festival Participants. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2010, 10, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.; Marques, C.; Loureiro, S.M.C. The dimensions of rural tourism experience: Impacts on arousal, memory, and satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-H.; Lin, R. Building a Total Customer Experience Model: Applications for the Travel Experiences in Taiwan’s Creative Life Industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radder, L.; Han, X. An Examination of The Museum Experience Based on Pine and Gilmore’s Experience Economy Realms. J. Appl. Bus. Res. (JABR) 2015, 31, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-H. The strategies of experiential design in the creative life industry. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference, CCD 2021, Gothenburg, Sweden, 24–29 July 2021; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L.; Swan, J.E. Consumer Perceptions of Interpersonal Equity and Satisfaction in Transactions: A Field Survey Approach. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Philos. Rhetor. 1975, 6, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Crompton, J.L. Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boo, S.; Busser, J.; Baloglu, S. A model of customer-based brand equity and its application to multiple destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Petrick, J.F. Examining the Antecedents of Brand Loyalty from an Investment Model Perspective. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odin, Y.; Odin, N.; Valette-Florence, P. Conceptual and operational aspects of brand loyalty: An empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 53, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Bianchi, C.; Kerr, G.; Patti, C. Consumer-based brand equity for Australia as a long-haul tourism destination in an emerging market. Int. Mark. Rev. 2010, 27, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Understanding brands, branding and brand equity. Interact. Mark. 2003, 5, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Pike, S.; Lings, I. Investigating attitudes towards three South American destinations in an emerging long haul market using a model of consumer-based brand equity (CBBE). Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Gursoy, D. An investigation of tourists’ destination loyalty and preferences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 13, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Ekinci, Y.; Whyatt, G. Brand equity, brand loyalty and consumer satisfaction. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1009–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.-L.; Hwang, S.-H.; Lee, C.-F. The life industry of the intention promotes and operates studying in Taiwan. J. Des. Res. 2005, 5, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-H.; Lin, R. Experiencing kansei space and qualia product in Creative Life Industries—A case study of The One Nanyuan Land of Retreat and Wellness. J. Kansei 2013, 1, 4–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, C.-T. The strategies of creative living industry in Taoyuan under the trend of experience economy. J. State Soc. 2015, 17, 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.L.; Ku, H.J.; Hwang, S.H. The construction of experience design in creative life industry—Take Shin-Gang incense artistic culture garden as an example. J. Sci. Technol. 2012, 21, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.-H. Applying experience types into the service design in Creative Life Industries—A case study of “Jioufen Teahouse”. J. Natl. Taiwan Coll. Arts 2018, 103, 123–149. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Son: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benbasat, I.; Goldstein, D.K.; Mead, M. The Case Research Strategy in Studies of Information Systems. MIS Q. 1987, 11, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1980, 79, 240. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G. In Taiwan, a Secluded Resort with Hot Tea Spas and Locavore Dining. Available online: https://cnaluxury.channelnewsasia.com/remarkable-living/taiwan-wellness-resort-one-nanyuan-192886 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Gaeavilla Brand Story. Available online: https://www.gaeavilla.com/en/about.php?act=story (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kensbock, S.; Jennings, G. Pursuing: A Grounded Theory of Tourism Entrepreneurs’ Understanding and Praxis of Sustainable Tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.A. Promoting teachers’ social and emotional competencies to support performance and reduce burnout. In Breaking the Mold of Preservice and Inservice Teacher Education: Innovative and Successful Practices for the Twenty-First Century; Cohan, A., Honigsfeld, A., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.M. Data Were Saturated... Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 587–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, I. Qualitative Data Analysis: A User-Friendly Guide for Social Scientists, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wildemuth, B.M. Qualitative analysis of content. In Applications of Social Research Methods to Applications to Question in Information and Library Science, 2nd ed.; Wildemuth, B.M., Ed.; Brooks/Cole: Belmont, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 318–329. [Google Scholar]

| Code | Gender | Age Group | Educational Background | Numbers of Visits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1-a | Male | 40–49 | Master | Once |

| C1-b | Female | 50–59 | Master | Once |

| C1-c | Female | 50–59 | Master | Once |

| C1-d | Male | 40–49 | Associate | Once |

| C1-e | Male | ≥60 | Master | More than once |

| C1-f | Female | 30–39 | Associate | Once |

| C1-g | Female | 30–39 | Associate | Once |

| C1-h | Female | 30–39 | Master | Once |

| C1-i | Female | 30–39 | Master | Once |

| C1-j | Female | 20–29 | Master | More than once |

| C2-a | Male | 50–59 | Associate | Once |

| C2-b | Female | 50–59 | Bachelor | Once |

| C2-c | Female | 30–39 | Master | Once |

| C2-d | Female | 20–29 | Master | Once |

| C2-e | Female | 50–59 | Bachelor | More than once |

| C2-f | Female | 50–59 | Master | Once |

| C2-g | Female | 50–59 | Bachelor | Once |

| C2-h | Male | ≥60 | Master | More than once |

| C2-i | Female | 20–29 | Master | More than once |

| C2-j | Female | 20–29 | Master | Once |

| Realms of Experience | Dimensions of Brand Loyalty | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme | Subthemes | Revisit Intention | Recommendation | Attachment |

| Number of Statements (Code of Participants) | ||||

| Entertainment | Relaxing and entertaining programs | 3 (C1-i, C1-h, C2-g) * | ||

| Education | Living esthetic program relatability | 5 (C1-f, C1-g, C1-i) * (C1-j, C2-h) ** | ||

| Esthetics | Architectural style and esthetics | 7 (C1-a, C1-c, C1-i, C2-c, C2-j) * (C1-e, C2-h) ** | 3 (C1-c, C2-c) * (C2-h) ** | |

| Escapism | Living design different from routine life | 8 (C1-c, C2-b, C2-d, C2-j, C2-f, C2-g) * (C1-e, C2-e) ** | 4 (C1-c, C2-c) * (C1-e, C2-h) ** | 4 (C1-f, C1-g, C2-c, C2-d) * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, S.-H. Eliciting Brand Loyalty with Elements of Customer Experience: A Case Study on the Creative Life Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811547

Chang S-H. Eliciting Brand Loyalty with Elements of Customer Experience: A Case Study on the Creative Life Industry. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811547

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Shu-Hua. 2022. "Eliciting Brand Loyalty with Elements of Customer Experience: A Case Study on the Creative Life Industry" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811547

APA StyleChang, S.-H. (2022). Eliciting Brand Loyalty with Elements of Customer Experience: A Case Study on the Creative Life Industry. Sustainability, 14(18), 11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811547