Strategic Management of External Disruptions on Realization of Business Plans—Case of Serbian Manufacturing Companies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- COVID-19 pandemic effects have massively hit Serbian enterprises regarding their influence on international trade, so government interventions helped by replacing the missing cash inflow;

- Supply chains were disrupted heavily, so the majority of placement focused on the domestic market, instead of the Balkans region (or European markets);

- SMEs’ coping strategies were adjusted due to low-interest loans from the government;

- SMEs maintained their number of employees because their salaries were being paid (financed) externally by the government.

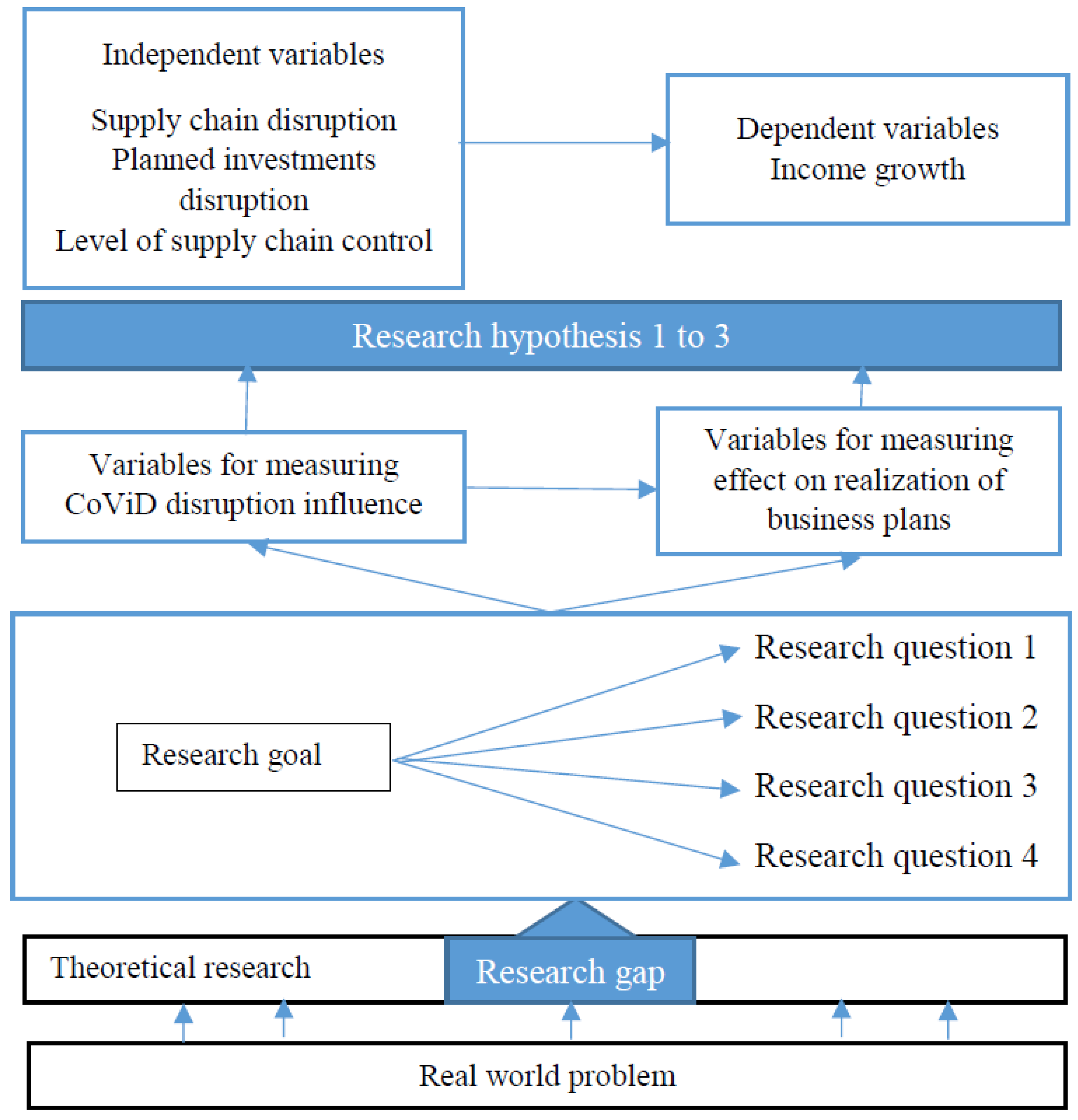

- RQ1. Is it possible to correlate business plan predictions empirically between the pre-COVID-19 (year 2019) and post-COVID-19 (year 2021) periods following the fact that predictions are more accurate if a company does not depend on the import of raw materials?

- RQ2. Is it possible to correlate business plan predictions empirically between the pre-COVID-19 (year 2019) and post-COVID-19 (year 2021) periods following the fact that predictions are more accurate if a company has predominant placement of their products on a domestic level?

- RQ3. Are companies participating in smaller supply chains less prone to bottlenecks (lower level of placement of finished goods)?

- RQ4. Is the future business outcome of a company directly affected by the direction and amount of planned investments?

- Whether the manufacturing company has international supply chain participants or is in full control of the supply chain;

- If the majority of the sales share comes from international or domestic destinations;

- Whether the supply chain in which it participates includes possible “bottleneck” participants.

- To identify key the effects of strategic management within a medium-sized manufacturing company through the influence of external disruptions on the realization of business plans (measured through planned income growth);

2. Literature Review

2.1. Import/Export Activities and Influence on Company Performance

2.2. Effect of Disruption on Direction and Implementation of Planned Investments

2.3. Influence of Supply Chain Bottlenecks on Company Business Sustainability

3. Methodology

3.1. Framework

- What supply chain section has been most at risk during the COVID-19 pandemic (import of raw materials, exports, placement in the country, internal reduction of manufacturing or raw materials from domestic suppliers)?

- To what extent did COVID-19 prevent planned investments in capacity growth (investments stopped entirely, investments carried out as planned, decreased when compared with plans or there was no intention to invest)?

- What is the level of internationalization of your business (fully international, only domestic, operates within an international supply chain or controls supply chain integrally)?

- Related to RQ1 and RQ3—Supply chain impact, measured through the number of individual participants in a supply chain or the level of integrity over supply chain activities;

- Related to RQ2—COVID-19 lockdown impact, measured through lowered import/export activities and demand depressions (forced redundancies and lower demand);

- Related to RQ4—Recovery, measured through planned investments that were successfully completed and the estimation of income growth in 2022.

3.2. Hypothesis Formulation and Variables Definition

- H1.Medium-sized manufacturing companies are less influenced by external disruptions in terms of business outcome if they are less dependent on import and export activities;

- H2.The predictability of company business outcomes is directly impacted by planned investments;

- H3.Medium-sized manufacturing companies are less influenced by external disruptions in terms of business outcomes if they control the supply chain integrally.

4. Results

4.1. Research Sample

- Belgrade—290 companies (10,000 in total, of which 4000 generate 80% of the total revenue of this region);

- Vojvodina—128 companies (4000 in total, of which 1000 generate 80% of the total revenue of this region);

- Sumadija and Western Serbia—102 companies (2000 in total, out of which 800 generate 80% of the total revenue of this region);

- South and East Serbia—60 companies (1000 in total, of which 400 generate 80% of the total revenue of this region).

4.2. Research Findings

- Import of raw materials highly correlates with an income decrease larger than 10% (correlations coefficient equals 0.39);

- Export of products/services correlates with a decline of income larger than 10% (correlations coefficient equals 0.41);

- Domestic market placement correlates with a decline in income larger than 10% (correlations coefficient equals 0.21).

- There was a slightly negative overall correlation for companies experiencing a decline in income larger than 10% in 2021;

- Predicted 2021 growth in income directly correlated with the completion of planned investments for 2021 (predictions made in 2019).

4.3. Hypothesis Testing—Statistical Significance

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings and Conclusions

5.2. Discussion of Research Findings

- The predictability of business results is directly influenced by the ability to carry out planned investments, as companies that have managed to carry out investments according to their plans recorded annual growth of income (or only a small decline). This conclusion presents an expansion of the results reported by Arsic [22] on selecting a strategy to avert a decline or stagnation phase in the company life cycle;

- Business success (measured through annual growth of income) is highly interdependent on the degree of internationalization, supply chain sustainability and control within the supply chain. This is complementary to other fast-track research conducted by Kraus [67], who focused on the preservation of business liquidity and the re-emergence of a modified business model (i.e., speeding up digital transformation projects) as a method for dealing with the aftermath of COVID-19;

- Minimizing the number of participants within the supply chain can present a factor of resilience, which can be quite useful in the case of large disruptions and shocks, which is fully in line with Dutton [68], who analyzed the pandemic and its primary effects of massive disruption on European enterprises;

- Sustainability during and after a major crisis is achieved by adequate balancing between the effects of investments (such as digitalization) and efficiency of supply chain resilience; similar factors were explored during the pandemic in a paper by Obrenovic [69], outlining financial discipline as the key strategic approach.

5.3. Limitations of the Conducted Research

5.4. Practical Implications

- From the business survival aspect, owners or CEOs of medium-sized manufacturing companies are strategically managing external shocks if their company is conducting business mainly on a domestic level and if they are in full control over their supply chain. This signifies that they are in a better position to avoid business decline or shutdown, and it also confirms that such companies should take more risks when planning investments in the midterm;

- From the business planning aspect, proper strategic management of external disruptions can maintain the sustainability of a business, but key elements of that strategy do not contribute to the further improvement of business performance if it does not take place to its full effect. Means for achieving better business performance while exploiting existing strategic leverage points mostly include creating good direction for investments for the future;

- From an organizational perspective, strategic business planning is still in its early developing stage in the Serbian business environment; this study can serve all decision makers who are conducting business in similar markets, as well as other researchers closely connected to the topic.

5.5. Future Research Plans

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Correlations | Income Growth: Predicted in Q1 2020 (Based on data from 2019, 2018 and 2017) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RQ: What Section of the Supply Chain do You Expect to Grow in the Midterm? * | Decline < −10% | Decline > 10% | Stagnation −1% and 0% | Growth 0–5% | Growth +5% |

| Import of raw materials | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.26 |

| Export of products/services | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Domestic market placement | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.36 |

| Internal reduction of manufacturing | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.2 | 0.11 |

| Raw materials from domestic suppliers | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.22 | −0.03 |

| RQ: What are your plans regarding investments in the midterm? | Decline < −10% | Decline > 10% | Stagnation −1% and 0% | Growth 0–5% | Growth +5% |

| We do not plan to invest at all | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| We will invest more in capacity growth | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| We will invest less in capacity growth | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.38 |

| Industry | Company Size (Approx Employee Number) | Average Years of Existence on the Market | Region of Serbia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food industry | 230 | 14 | Vojvodina |

| Machines and parts manufacturers | 90 | 18 | South Serbia and Vojvodina |

| Textile industry | 160 | 22 | South and East Serbia |

Appendix B

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | Std Coefficient | t-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply chain—threatened raw material imports | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 2.99 | 0.01 |

| Impact of the pandemic on carrying out planned investment | 0.88 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 2.11 | 0.03 |

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | Std Coefficient | t-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of the pandemic on carrying out planned investment | 0.75 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 1.33 | 0.02 |

| Supply chain—threatened export | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 1.81 | 0.03 |

| All planned investments halted until the end of the pandemic | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 1.65 | 0.04 |

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | Std Coefficient | t-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply chain—threatened exports | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.023 | 0.44 | 0.09 |

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | Std Coefficient | t-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply chain—threatened exports | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.54 | 0.15 |

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | Std Coefficient | t-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of the pandemic on carrying out planned investment | 0.76 | 0.12 | 0.2 | 1.99 | 0.05 |

References

- Grover, A.; Karplus, V.J. Coping with COVID-19, World Bank Research Paper. 2021. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/829711611084759307/pdf/Coping-with-COVID-19-Does-Management-Make-Firms-More-Resilient.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachman, D. The Economic Impact of COVID-19 (Novel Coronavirus), Deloitte Study. 2020. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/insights/economy/covid-19/economic-impact-covid-19.html (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- National Bank of Serbia. Macroeconomic Developments in Serbia; National Bank of Serbia: Beograd, Serbia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bakator, M.; Ćoćkalo, D.; Đorđević, D.; Bogetić, S. The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: Reviewing Serbian and global strategies. Econ. Enterp. 2020, 69, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Investment Bank. COVID-19 Serbian Government Support SMEs&Midcaps. 2020. Available online: https://www.eib.org/en/projects/all/20200562 (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- KPMG. Government and Institution Measures in Response to COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2020/04/serbia-government-and-institution-measures-in-response-to-covid.html (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- UNECE. The Impact of COVID-19 on Trade and Structural Transformation in Serbia, UN Study, Switzerland. 2021. Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/Impact_COVID-19_Serbia-Eng.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Chinn, D.; Klier, J.; Stern, S.; Tesfu, S. Safeguarding Europe’s Livelihoods: Mitigating the Employment Impact of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Public%20Sector/Our%20Insights/Safeguarding%20Europes%20livelihoods%20Mitigating%20the%20employment%20impact%20of%20COVID%2019/Safeguarding-Europes-livelihoods-Mitigating-the-employment-impact-of-COVID-19-F.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Hossain, M.R.; Akhter, F.; Sultana, M.M. SMEs in COVID-19 Crisis and Combating Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) and A Case from Emerging Economy. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2022, 9, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udovicki, K.; Danon, M.; Medić, P.; Marković, B.; Tatić, T.; Radovanović, M. The COVID-Crisis and Serbia’s SMEs: Assessment of Impact and Outline of Future Scenarios, World Bank Research Study. 2020. Available online: https://ceves.org.rs/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/WB-Covid-19_-Report-final.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Anastasijević, J.; Corradin, F.; Sartore, D.; Uvalić, M.; Volo, F. Prospective Analysis of the SME Sector in the Western Balkans, European Investment Bank Study. 2021. Available online: http://www.wbedif.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/REPORT_final.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Varum, C.A.; Rocha, V.C. Employment and SMEs during crises. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máñez, J.A.; Rochina Barrachina, M.E.; Sanchis, J.A. The effects of export and R&D strategies on companies’ markups in downturns: The Spanish case. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 60, 634–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meramveliotakis, G.; Manioudis, M. Sustainable Development, COVID-19 and Small Business in Greece: Small Is Not Beautiful. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual Ivars, J.V.; Comeche Martínez, J.M. The effect of high performance work systems on small and medium size enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1463–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, L.; Kennedy, B.; Tucci, A.; Velazquez, B.; Nolte, S.; Kutlina-Dimitrova, Z. Trade Policy Reflections beyond the COVID19. 2020. Available online: https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2020/july/tradoc_158859.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Whelan, T.; Fink, C. The Comprehensive Business Case for Sustainability. Harvard Business Review, Sustainable Business Practices. 21 October 2016. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/10/the-comprehensive-business-case-for-sustainability (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, E.C. Measuring the persistence of high firm growth: Choices and consequences. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 56, 451–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukmirović, V.; Kostić-Stanković, M.; Pavlović, D.; Ateljević, J.; Bjelica, D.; Radonić, M.; Sekulić, D. Foreign Direct Investments’ Impact on Economic Growth in Serbia. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2021, 23, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsić, S.; Banjević, K.; Nastasić, A.; Rošulj, D.; Arsić, M. Family Business Owner as a Central Figure in Customer Relationship Management. Sustainability 2018, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khin, A.A.; Chiun, F.Y.; Seong, L.C. Identifying the Factors of the Successful Implementation of Belt and Road Initiative on Small–Medium Enterprises in Malaysia. China Rep. 2019, 55, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, O.A.; Medda, G. Linkages between R&D, innovation, investment and export performance: Evidence from European manufacturing companies. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 32, 1379–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabić, M.; Lažnjak, J.; Smallbone, D.; Švarc, J. Intellectual capital, organisational climate, innovation culture, and SME performance: Evidence from Croatia. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2019, 26, 522–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.Y.M.; Webster, C.M. Influence of Innovativeness, Environmental Competitiveness and Government, Industry and Professional Networks on SME Export Likelihood. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 1304–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Luo, J. Influence of COVID-19 on Manufacturing Industry and Corresponding Countermeasures from Supply Chain Perspective. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Sci.) 2020, 25, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerschewski, S.; Evers, N.; Nguyen, A.T.; Froese, F.J. Trade Shows and SME Internationalisation: Networking for Performance. Manag. Int. Rev. 2020, 60, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamiatzi, V.C.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Role of Human and Social Capital Traits in SMEs Over-Performance During Industrial Downturns: Theoretical Development. SSRN Electron. J. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iborra, M.; Safón, V.; Dolz, C. What explains resilience of SMEs? Ambidexterity capability and strategic consistency. Long Range Plan. 2019, 53, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatoglu, E.; Bayraktar, E.; Golgeci, I.; Koh, S.C.L.; Demirbag, M.; Zaim, S. How do supply chain management and information systems practices influence operational performance? Evidence from emerging country SMEs. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2016, 19, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asgary, A.; Ozdemir, A.I.; Özyürek, H. Small and Medium Enterprises and Global Risks: Evidence from Manufacturing SMEs in Turkey. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Gongbing, B.; Mehreen, A. Supply chain network and information sharing effects of SMEs’ credit quality on firm performance: Do strong tie and bridge tie matter? J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 32, 714–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Gu, J.; Fujita, H. Alleviating Financing Constraints of SMEs through Supply Chain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.; Woo, H.; Yang, J.S. Opposite effects of R&D cooperation on financial and technological performance in SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 60, 892–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiyevskyy, O.; Shirokova, G.; Ritala, P. SMEs’ Adaptation to Economic Downturns: The Impact of Exploration and Exploitation on Performance. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2019, 2019, 10061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, M.; Brown, R.; Rocha, A. Did you save some cash for a rainy COVID-19 day? The crisis and SMEs. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2020, 38, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garagorri, I. SME vulnerability analysis: A tool for business continuity. In Competitive Strategies for Small and Medium Enterprises: Increasing Crisis Resilience, Agility and Innovation in Turbulent Times; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meslier, C.; Sauviat, A.; Yuan, D. Comparative advantages of regional versus national banks in alleviating SME’s financial constraints. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2020, 71, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.; Han, S.H.; Lee, D.H. SME profitability of trade credit during and after a financial crisis: Evidence from Korea. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbó-Valverde, S.; Rodríguez-Fernández, F.; Udell, G.F. Trade Credit, the Financial Crisis, and SME Access to Finance. J. Money Credit. Bank. 2016, 48, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bianchi, C.; Abu Saleh, M. Investigating SME importer–foreign supplier relationship trust and commitment. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, F. Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partanen, J.; Kohtamäki, M.; Patel, P.C.; Parida, V. Supply chain ambidexterity and manufacturing SME performance: The moderating roles of network capability and strategic information flow. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 221, 107470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, C.; Carew, D.; Shatz, H. Preserving Small Businesses: Small-Business Owners Speak about Surviving the COVID-19 Pandemic; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, T. SME routes for innovation collaboration with larger enterprises. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 64, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benigno, G.; di Giovanni, J.; Groen, J.; Noble, A.I. A New Barometer of Global Supply Chain Pressures, Liberty Street Economics. 2022. Available online: https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/01/a-new-barometer-of-global-supply-chain-pressures/ (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Kapoor, K.; Bigdeli, A.Z.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Raman, R. How is COVID-19 altering the manufacturing landscape? A literature review of imminent challenges and management interventions. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussoli, C.; Marino, F. Trade credit in times of crisis: Evidence from European SMEs. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2018, 25, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.A.; Tanisa, T.; Sakib, K.M.N. Associating MFIs with SMEs to Assist Post Pandemic Economic Resilience in Bangladesh. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, N.M.; Dicken, P.; Hess, M. Global production networks: Realizing the potential. J. Econ. Geogr. 2008, 8, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. Integrating SMEs into Global Value Chains Challenges and Policy Actions in Asia. 2015. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/175295/smes-global-value-chains.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Hamilton, D.S. Advancing Supply Chain Resilience and Competitiveness: Recommendations for U.S.-EU Action, Transatlantic Organization. 2021. Available online: https://www.transatlantic.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/TTC-Supply-Chains.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Wellalage, N.H.; Fernandez, V. Innovation and SME finance: Evidence from developing countries. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2019, 66, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.M. Effect of partnership quality on SMEs success: Mediating role of coordination capability and organisational agility. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2020, 32, 1786–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar Singh, R. Coordination and responsiveness issues in SME supply chains: A review. Benchmarking 2017, 24, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semrau, T.; Ambos, T.; Kraus, S. Entrepreneurial orientation and SME performance across societal cultures: An international study. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1928–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraha, I.; Đuričin, S. The Impact of COVID-19 Crisis on Medium-sized Enterprises in Serbia. Digital repositorium of Institute for economic sciences in Belgrade. Econ. Anal. Appl. Res. Emerg. Mark. 2020, 53, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Shashi, S.; Cerchione, R.; Centobelli, P.; Shabani, A. Sustainability orientation, supply chain integration, and SMEs performance: A causal analysis. Benchmarking 2018, 25, 3679–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibin, K.T.; Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Hazen, B.; Roubaud, D.; Gupta, S.; Foropon, C. Examining sustainable supply chain management of SMEs using resource based view and institutional theory. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 290, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Trade Centre. SME Competitiveness Outlook 2020—COVID-19: The Great Lockdown and its Effects of Small Business. 2020. Available online: https://www.intracen.org/publication/smeco2020/ (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- McKibbin, W.; Fernando, R. The Global Macroeconomic Impacts of COVID-19: Seven Scenarios. Asian Econ. Pap. 2020, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, B.; Anicic, Z. Impact of the covid-19 crisis on smes and possible innovation responses. Econ. Enterp. 2021, 69, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.; Weder, B.; Mauro, D. Introduction. In Economics in the Time of COVID-19; CEPR: 2020. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Arauzo Carod, J.; Marti, F.P. Spatial distribution of economic activities: A network approach. J. Econ. Interact. Coord. 2020, 15, 441–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairlie, R. The impact of COVID-19 on small business owners: Evidence from the first three months after widespread social-distancing restrictions. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2020, 29, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Clauss, T.; Breier, M.; Gast, J.; Zardini, A.; Tiberius, V. The economics of COVID-19: Initial empirical evidence on how family companies in five European countries cope with the corona crisis. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1067–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, S. From Disruption to Advantage: Supply Chain Resilience and Decarbonisation in Europe, Euromonitor International. 2022. Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/article/from-disruption-to-advantage-supply-chain-resilience-and-decarbonisation-in-europe (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Obrenovic, B.; Du, J.; Godinic, D.; Tsoy, D.; Khan, M.A.S.; Jakhongirov, I. Sustaining Enterprise Operations and Productivity during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Enterprise Effectiveness and Sustainability Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; Stanske, S.; Lieberman, M.B. Strategic responses to crisis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, O16–O27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Rio-Chanona, R.M.; Mealy, P.; Pichler, A.; Lafond, F.; Farmer, D. Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic: An industry and occupation perspective. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36, S94–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group of Variables | Value of Variable | Independent Variable | Standardized Value of Variable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income: actual result in 2021 vs. that predicted in Q1 2020 | Growth larger than 5% | Y1 | (0,1) |

| Decline larger than 10% | Y2 | (0,1) | |

| Decline less than 10% | Y3 | (0,1) | |

| Stagnation (decline btw 0 and −1%) | Y4 | (0,1) | |

| Growth up to 5% | Y5 | (0,1) | |

| COVID-19 disruption to supply chain | Import of raw materials | X1 | (0,1) |

| Export of products/services | X2 | (0,1) | |

| Domestic market placement | X3 | (0,1) | |

| Internal reduction of manufacturing | X4 | (0,1) | |

| Raw materials from domestic supplier | X5 | (0,1) | |

| COVID-19 disruption to planned investments | Stopped entirely | X6 | (0,1) |

| Decreased when compared to initially planned in 2020 | X7 | (0,1) | |

| Carried out as planned | X8 | (0,1) | |

| No intention to invest for the duration of the pandemic | X9 | (0,1) | |

| Stopped entirely | X10 | (0,1) | |

| Supply chain level of control | Internationalized | X11 | (0,1) |

| Only domestic market | X12 | (0,1) | |

| Operates within a supply chain | X13 | (0,1) | |

| Controls supply chain integrally | X14 | (0,1) |

| Company Size | 50–100 | 101–200 | 201–249 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of companies—phase 1 (share of total) | 180 (28%) | 20 (0.03%) | 298 (51%) | 35 (5.4%) | 102 (18%) | 5 (0.01%) |

| Number of companies—phase 2 (share of total) | 202 (34.8%) | 0 * | 286 (49.3%) | 0 * | 92 (15.8%) | 0 * |

| Correlations | Income Growth: 2021 vs. Predicted in Q1 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What Supply Chain Section Has Been Most at Risk during the COVID-19 Pandemic? | Decline < −10% | Decline > 10% | Stagnation −1% and 0% | Growth 0–5% | Growth +5% |

| Import of raw materials | −0.22 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.38 |

| Export of products/services | 0.31 | −0.20 | −0.33 | 0.04 | −0.01 |

| Domestic market placement | 0.29 | −0.11 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.19 |

| Internal reduction of manufacturing | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.11 | 0.11 |

| Raw materials from domestic suppliers | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.02 | −0.03 |

| Correlations | Income Growth: Actual Result in 2021 vs. Predicted in Q1 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To What Extent Did COVID-19 Prevent Planned Investments in Capacity Growth? | <−10% | Decline less than 10% | Stagnation −1% and 0% | 0–5% | +5% |

| Stopped entirely | −0.39 | −0.02 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Decreased when compared with that initially planned in 2020 | −0.31 | −0.02 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| Carried out as planned | −0.02 | −0.10 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.38 |

| No intention to invest for the duration of the pandemic | −0.36 | −0.24 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Dependent Variables | Company Group | ANOVA (Variability Sources Inside and Between Groups) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squares | Mean of Squares | F Test p-Value | ||||

| Between Groups | Within Groups | Between Groups | Within Groups | |||

| Y1, Y2, Y3, Y4 and Y5—actual income for 2021 vs. predicted income (from 2020) | Internationalized | 416,564 | 345,199 | 13,601 | 9952 | F 21.12 p-value < 0.01 |

| Only domestic market | 216,323 | 215,787 | 378,508 | 170,747 | F 28.11 p-value < 0.01 | |

| Operates within a supply chain | 393,053 | 223,133 | 129,941 | 6563 | F 26.52 p-value < 0.01 | |

| Controls supply chain integrally | 116,711 | 225,232 | 218,010 | 145,997 | F 27.54 p-value < 0.01 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Damnjanovic, A.M.; Dzafic, G.; Nesic, S.; Milosevic, D.; Mrdak, G.; Arsic, S.M. Strategic Management of External Disruptions on Realization of Business Plans—Case of Serbian Manufacturing Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811583

Damnjanovic AM, Dzafic G, Nesic S, Milosevic D, Mrdak G, Arsic SM. Strategic Management of External Disruptions on Realization of Business Plans—Case of Serbian Manufacturing Companies. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811583

Chicago/Turabian StyleDamnjanovic, Aleksandar M., Goran Dzafic, Sandra Nesic, Dragan Milosevic, Gordana Mrdak, and Sinisa M. Arsic. 2022. "Strategic Management of External Disruptions on Realization of Business Plans—Case of Serbian Manufacturing Companies" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811583