Can Supplier Concentration Improve Corporate Risk Taking? Moderating Effects of Digital Transformation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Risk Taking

2.2. Supplier Concentration

2.3. Enterprise Digital Transformation

3. Hypothesis Development

4. Data and Methodology

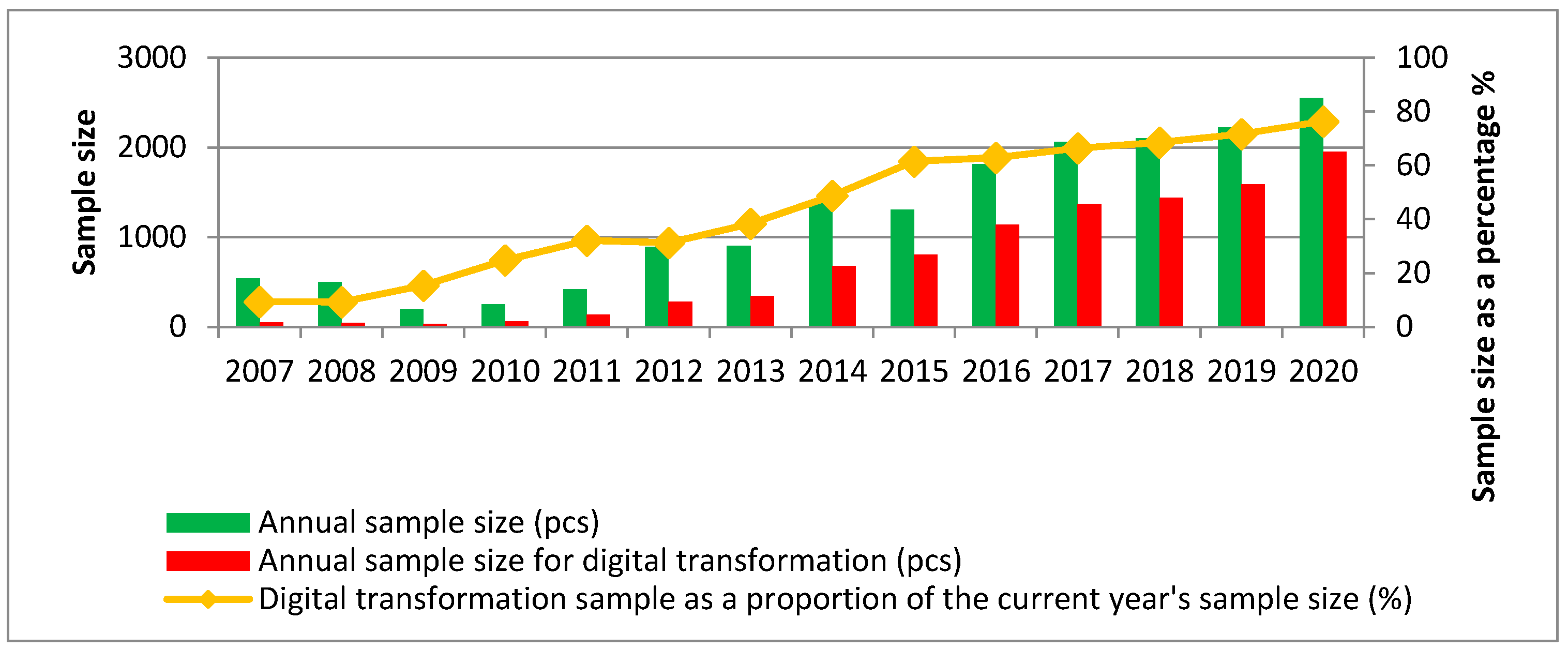

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

4.2. Variable Descriptions

4.2.1. Dependent Variable

4.2.2. Independent Variable

4.2.3. Moderator Variable

4.2.4. Control Variables

4.3. Empirical Models

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Correlation Analysis

5.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

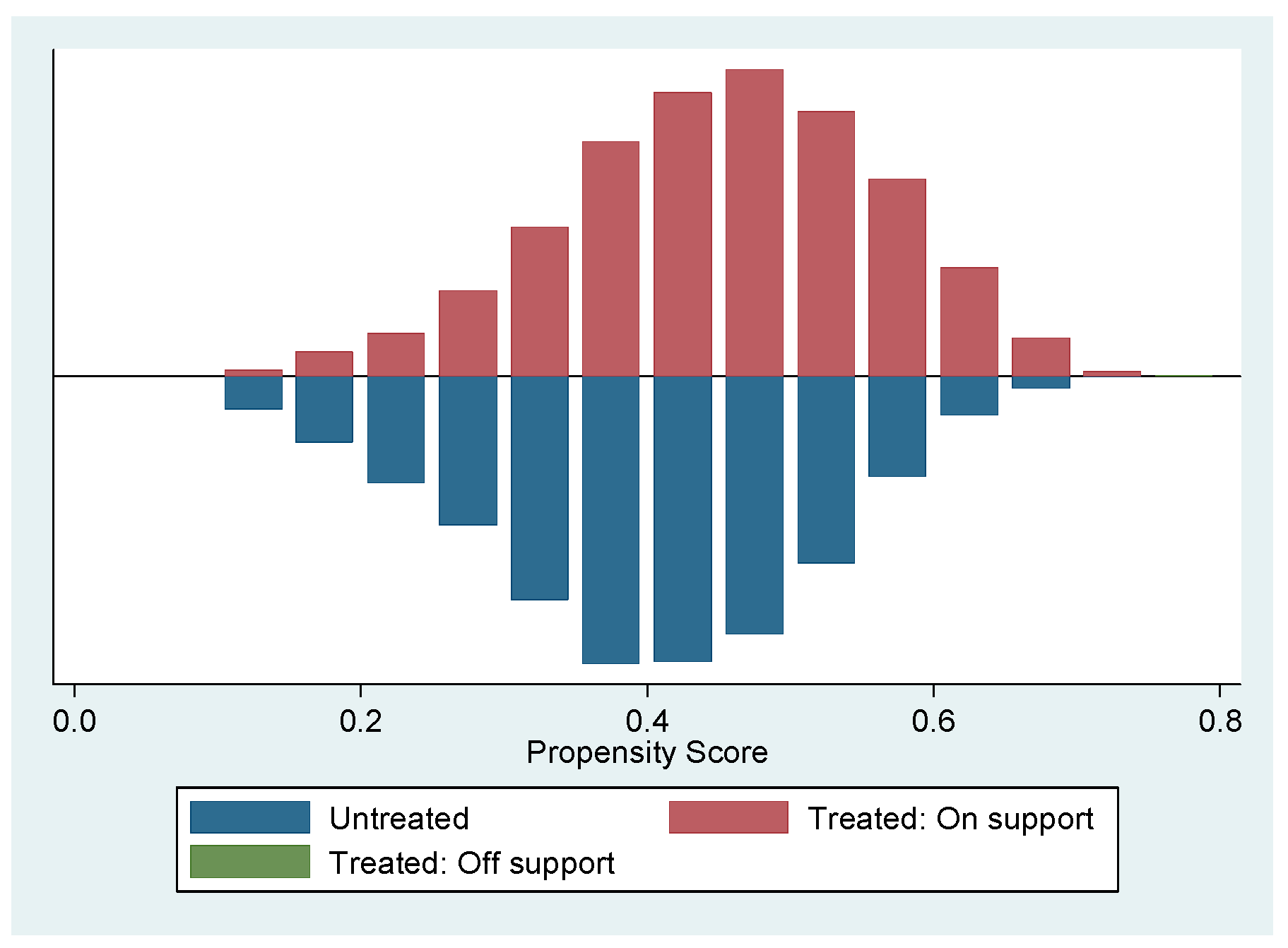

5.4. Robustness Check

5.5. Enterprise Digital Transformation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Symbols | Variable Definitions |

|---|---|

| Risk1 | Calculated from Equation (2) |

| Risk2 | Calculated from Equation (3) |

| Supply | Top five suppliers’ purchases as a proportion of total annual corporate purchases (%) |

| Lev | Financial leverage, measured by the ratio of current liabilities to assets |

| Size | Natural logarithm of total assets |

| Age | natural logarithm of (current year − year the company was listed + 1) |

| Dual | A value of 1 is assigned when the positions of chairman and general manager are held by one person, otherwise a value of 0 is assigned. |

| Board | Natural logarithm of the total number of board members |

| Idep | Proportion of independent directors in the board members |

| Mstop | Natural logarithm of the total remuneration of the top three executives |

| year | Annual dummy variables |

| ind | Industry dummy variables |

References

- Yu, M.G.; Li, W.G.; Pan, H.B. Managerial overconfidence and corporate risk-taking. Financ. Res. 2013, 1, 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. Intelligent manufacturing—The main direction of “made in China 2025”. China Mech. Eng. 2015, 26, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.M.; Quan, X.F.; Zhu, S.S. Supply chain concentration and firm innovation: An empirical study based on Chinese listed manufacturing firms. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2022, 42, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Q. Accounting governance of relationship based transactions-A paradigm exploration on the internationalization of accounting research in China. Financ. Res. 2017, 43, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, L.G.; Shao, J.B. Digital transformation, supply chain integration and firm performance—The moderating effect of entrepreneurship. Econ. Manag. 2021, 10, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.X.; Wu, F.; Chang, X. Corporate digital transformation process and main business performance-empirical evidence from text identification of Chinese listed firms’ annual reports. Mod. Financ. Econ. 2021, 381, 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.D.; Yu, J.; Wei, J. Digital innovation management: Theoretical framework and future research. Manag. World 2020, 36, 198–217. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Benlian, A. Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Q. Exec. 2016, 15, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hilary, G.; Huik, W. Does religion matter in corporate decision making in America? J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.; Litov, L.; Yeung, B. Corporate Governance and Risk Taking. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1679–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyav, V.; Amihud, Y.; Litov, L. Creditor Rights and Corporate Risk-taking. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 102, 150–166. [Google Scholar]

- Mclean, R.D.; Zhao, M. The Business Cycle, Investor Sentiment, and Costly External Finance. J. Financ. 2014, 69, 1377–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.P.; Ailing, L.X. Industrial policy support, enterprise life cycle and risk-taking. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 1, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.P.; Sun, Y. A study of monetary policy risk-taking channels for microlending data a perspective based on bank characteristics, borrowing firm characteristics and loan contract characteristics. Econ. Econ. 2020, 37, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, C.F.; Peng, T.; Guo, J. Policy uncertainty and firm risk-taking: Opportunity anticipation effect or loss aversion effect. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T.; Huang, F.G.; Sun, L.X. Economic policy uncertainty and risk-taking: Evidence based on venture capital. J. Manag. Sci. 2021, 24, 98–114. [Google Scholar]

- Faccio, M.; Marchicam, T.; Mura, R. Large Shareholder Diversification and Corporate Risk-Taking. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2011, 24, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Zhang, R.J. Equity incentives affect risk-taking: Agency costs or risk aversion? Account. Res. 2014, 1, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.L.; Fang, C.J. CEO power, executive team pay gap and corporate risk-taking. Econ. Econ. 2018, 35, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Cui, Y.; Zheng, Y. The Impact of Corporate Strategy on Enterprise Innovation Based on the Mediating Effect of Corporate Risk-Taking. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1023. [Google Scholar]

- Faccio, M.; Marchica, M.; Mura, R. CEO Gender, Corporate Risk-Taking, and the Efficiency of Capital Allocation. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 39, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.X.; Wang, S.Q.; Li, X.Q. Executive team disruption and corporate risk-taking-the moderating role of the CEO-TMT power gap. Soft Sci. 2022, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.C.; Song, Y.F. An empirical study on the impact of supply chain concentration on the intensity of corporate R&D investment—The moderating role of the nature of property rights. Res. Dev. Manag. 2019, 31, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, D.; Judd, J.S.; Serfling, M. Customer concentration risk and the cost of equity capital. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2016, 61, 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lanier, D., Jr.; Wempe, W.F.; Zacharia, Z.G. Concentrated supply chain membership and financial performance: Chain and firm-level perspectives. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.W.; Klasa, S.; Yeung, P.E. Corporate suppliers and customers and accounting conservatism. J. Account. Econ. 2012, 52, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Pan, J.P.; Dai, Y.Y. Corporate litigation risk, judicial local protectionism and corporate innovation. Econ. Res. 2015, 3, 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.X.; Zhang, Y. Supplier/customer relationship-based transactions, surplus management and auditor decision making. Account. Res. 2016, 1, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, K.; Shahrur, H. Relationship-specific investments and earnings management: Evidence on corporate suppliers and customers. Account. Rev. 2008, 83, 1041–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Bao, Q. Institutional environment, relationship transactions and cash holding decisions. Audit Econ. Res. 2015, 30, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.M.; Fernandes, C.I.; Ferreira, F.A. To be or not to be digital, that is the question: Firm innovation and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.Y.; Wang, W.C.; Li, X.S. How digital transformation affects total factor productivity of enterprises. Financ. Trade Econ. 2021, 42, 114–129. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Li, Z. Is There Any Difference in the Impact of Digital Transformation on the Quantity and Efficiency of Enterprise Technological Innovation? Taking China’s Agricultural Listed Companies as an Example. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q. Mechanism and performance of enterprise digital transformation. Zhejiang Acad. J. 2020, 3, 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Meng, Q.S.; Zhang, Y. Digital innovation: Exploration and enlightenment from new perspectives of innovation research. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2017, 35, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.H.; Xing, M.Q. The degree of industry competition, supplier concentration and cash flow manipulation. Econ. Issues 2021, 5, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X. Why are social network transactions important? Evidence based on the concentration of key suppliers and customers in China. China J. Account. Res. 2011, 4, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.L.; Yang, L.G. Does accounting information transparency improve corporate risk-taking? Financ. Theory Pract. (Bimon.) 2021, 42, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Han, J.P. The impact of open innovation on the growth of start-ups in the digital context: The mediating role of business model innovation. Manag. Rev. 2019, 31, 186–198. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, J. Digital transformation of enterprises and enterprise value. Contemp. Financ. Stud. 2022, 5, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H.J.; Cao, X.Q.; Liu, Y.X. The impact of digital economy on corporate governance-based on the perspective of information asymmetry and managers’ irrational behavior. Reform 2020, 4, 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, A.; Rubin, A. Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Liu, H.X. Assessment of the performance enhancement effect of digital change in real enterprises from the perspective of digital economy. Reform 2019, 4, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.H.; Wang, M.S. A study on the governance effect of digital transformation on excessive financialization of real enterprises. Secur. Mark. Her. 2022, 6, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

| Panel A | Sample Size | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | P50 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk1 | 17,140 | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.004 | 0.044 | 0.395 |

| Risk2 | 17,140 | 0.115 | 0.111 | 0.007 | 0.084 | 0.72 |

| Supply | 17,140 | 0.344 | 0.186 | 0.066 | 0.303 | 0.914 |

| Lev | 17,140 | 0.393 | 0.201 | 0.048 | 0.380 | 0.99 |

| Age | 17,140 | 2.827 | 0.346 | 1.609 | 2.890 | 3.466 |

| Board | 17,140 | 2.114 | 0.192 | 1.609 | 2.197 | 2.639 |

| Idep | 17,140 | 0.375 | 0.053 | 0.313 | 0.333 | 0.571 |

| Mstop | 17,140 | 14.31 | 0.733 | 12.239 | 14.301 | 16.213 |

| Size | 17,140 | 21.873 | 1.15 | 19.555 | 21.732 | 25.306 |

| Dual | 17,140 | 0.049 | 0.216 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Panel B | high supplier concentration | low supplier concentration | T-test in means | |||

| n | mean | n | mean | Coefficient | T | |

| Risk1 | 7217 | 0.063 | 9923 | 0.059 | 0.0039 *** | 4.22 |

| Risk2 | 7217 | 0.119 | 9923 | 0.112 | 0.007 *** | 4.10 |

| Panel C | digital transformation | Nondigital transformation | T-test in means | |||

| n | Mean | n | Mean | Coefficient | T | |

| Risk1 | 9912 | 0.062 | 7228 | 0.06 | 0.002 ** | 2.21 |

| Risk2 | 9912 | 0.116 | 7228 | 0.112 | 0.004 ** | 2.33 |

| Supply | 9912 | 0.325 | 7228 | 0.372 | −0.047 *** | −16.53 |

| Risk1 | Risk2 | Supply | Lev | Age | Board | Idep | Mstop | Size | Dual | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk1 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Risk2 | 0.998 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Supply | 0.042 *** | 0.041 *** | 1.000 | |||||||

| Lev | 0.0601 *** | 0.058 *** | −0.096 *,** | 1.000 | ||||||

| Age | 0.0149 ** | 0.016 ** | −0.028 *** | 0.108 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| Board | −0.027 *** | −0.028 *** | −0.058 *** | 0.129 *** | 0.004 | 1.000 | ||||

| Idep | 0.0172 ** | 0.018 ** | −0.007 | −0.009 | 0.018 ** | −0.564 *** | 1.000 | |||

| Mstop | 0.0269 *** | 0.029 *** | −0.172 *** | −0.017 ** | 0.217 *** | 0.042 *** | 0.009 | 1.000 | ||

| Size | −0.045 *** | −0.045 *** | −0.251 *** | 0.408 *** | 0.209 *** | 0.212 *** | −0.002 | 0.442 *** | 1.000 | |

| Dual | 0.0175 ** | 0.0189 ** | 0.0681 *** | −0.1504 *** | −0.1024 *** | −0.0506 *** | 0.0251 *** | 0.0147 | −0.1532 *** | 1 |

| Full Sample | High Supplier Concentration | Low Supplier Concentration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| Risk1 | Risk2 | Risk1 | Risk2 | Risk1 | Risk2 | |

| Supply | 0.013 *** (4.47) | 0.023 *** (4.39) | 0.018 *** (3.10) | 0.033 *** (3.17) | 0.002 (0.29) | 0.003 (0.19) |

| Lev | 0.0345 *** (9.63) | 0.063 *** (9.57) | 0.046 *** (8.45) | 0.084 *** (8.42) | 0.024 *** (5.06) | 0.043 *** (5.01) |

| Age | −0.003 *** (−2.23) | −0.006 ** (−2.14) | −0.004 (−1.51) | −0.007 (−1.53) | −0.004 * (−1.88) | −0.006 * (−1.74) |

| Board | −0.002 (−0.71) | −0.005 (−0.79) | −0.001 (−0.17) | −0.001 (−0.10) | −0.005 (−1.35) | −0.010 (−1.41) |

| Idep | 0.007 (0.73) | 0.014 (0.73) | 0.023 (1.28) | 0.043 (1.28) | −0.003 (−0.27) | −0.006 (−0.27) |

| Mstop | 0.003 *** (4.00) | 0.006 *** (4.15) | 0.003 ** (2.07) | 0.005 ** (2.12) | 0.003 *** (3.25) | 0.006 *** (3.39) |

| Size | −0.0047 *** (−7.70) | −0.008 *** (−7.71) | −0.006 *** (−5.98) | −0.011 *** (−6.00) | −0.004 *** (−4.56) | −0.007 *** (−4.60) |

| Dual | 0.005 ** (2.27) | 0.009 ** (2.42) | 0.008 *** (2.58) | 0.015 *** (2.74) | 0.001 (0.50) | 0.003 (0.53) |

| _cons | 0.125 *** (8.25) | 0.230 *** (8.25) | 0.142 *** (5.09) | 0.246 *** (5.14) | 0.116 *** (6.36) | 0.212 *** (6.35) |

| ind | Yes | yes | Yes | Yes | yes | yes |

| year | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| N | 17140 | 17140 | 7217 | 7217 | 9923 | 9923 |

| adj. R-sq | 0.055 | 0.056 | 0.065 | 0.065 | 0.051 | 0.052 |

| Panel A: Substitution of independent variables | ||||

| variable | Risk1 | Risk2 | ||

| Coefficient | T-value | Coefficient | T-value | |

| Supply | 0.025 *** | 3.14 | 0.045 *** | 3.11 |

| Controls | yes | yes | ||

| _cons | 0.097 *** | 3.65 | 0.187 *** | 3.69 |

| n | 11,952 | 11,952 | ||

| R-sq | 0.076 | 0.076 | ||

| Panel B: Heckman two-step method | ||||

| Dependent variable: Risk1 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | ||

| Coefficient | Z-value | Coefficient | T-value | |

| Supply | −0.421 *** | −2.58 | 0.012 *** | 4.19 |

| imr | 0.381 *** | 7.81 | ||

| Controls | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| _cons | 0.663 *** | 11.61 | 0.169 *** | 9.20 |

| n | 17,140 | 17,140 | ||

| R-sq | 0.238 | 0.073 | ||

| Panel C: PSM test | ||||

| Methods | Treated Group N | Control Group N | ATT | T-Value |

| nearest neighbor matching | 7202 | 4381 | 0.004 | 2.872 *** |

| radius matching | 7163 | 9883 | 0.003 | 3.312 *** |

| kernel matching | 7202 | 9906 | 0.4788 | 18.72 *** |

| Variable | Nondigital Transformation | Digital Transformation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk1 | Risk2 | Risk1 | Risk2 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Supply | 0.007 * (1.82) | 0.014 * (1.80) | 0.0174 *** (4.34) | 0.032 *** (4.25) |

| Lev | 0.035 *** (6.75) | 0.063 *** (6.71) | 0.033 *** (6.17) | 0.061 *** (6.67) |

| Age | −0.001 (−0.62) | −0.002 (−0.58) | −0.005 ** (−2.249) | −0.009 ** (−2.40) |

| Board | −0.003 (−0.65) | −0.006 (−0.66) | −0.003 (−0.67) | −0.006 (−0.76) |

| Idep | 0.009 (0.57) | 0.016 (0.53) | 0.006 (0.45) | 0.012 (0.49) |

| Mstop | 0.0001 (0.17) | 0.001 (0.36) | 0.006 *** (5.20) | 0.011 *** (5.21) |

| Size | −0.004 *** (−4.70) | −0.008 *** (−4.74) | −0.005 *** (−5.96) | −0.009 *** (−5.96) |

| Dual | 0.005 * (1.80) | 0.010 * (1.89) | 0.005 (1.52) | 0.009 (1.64) |

| _cons | 0.152 *** (6.55) | 0.277 *** (6.52) | 0.096 *** (4.40) | 0.178 *** (4.40) |

| N | 7228 | 7228 | 9912 | 9912 |

| adj. R-sq | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.058 | 0.059 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Guo, J. Can Supplier Concentration Improve Corporate Risk Taking? Moderating Effects of Digital Transformation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811664

Yang Y, Guo J. Can Supplier Concentration Improve Corporate Risk Taking? Moderating Effects of Digital Transformation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811664

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yuanxi, and Jingxian Guo. 2022. "Can Supplier Concentration Improve Corporate Risk Taking? Moderating Effects of Digital Transformation" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811664

APA StyleYang, Y., & Guo, J. (2022). Can Supplier Concentration Improve Corporate Risk Taking? Moderating Effects of Digital Transformation. Sustainability, 14(18), 11664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811664