How Institutional Pressure Affects Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: The Moderated Mediation Effect of Green Management Practice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Literature Review

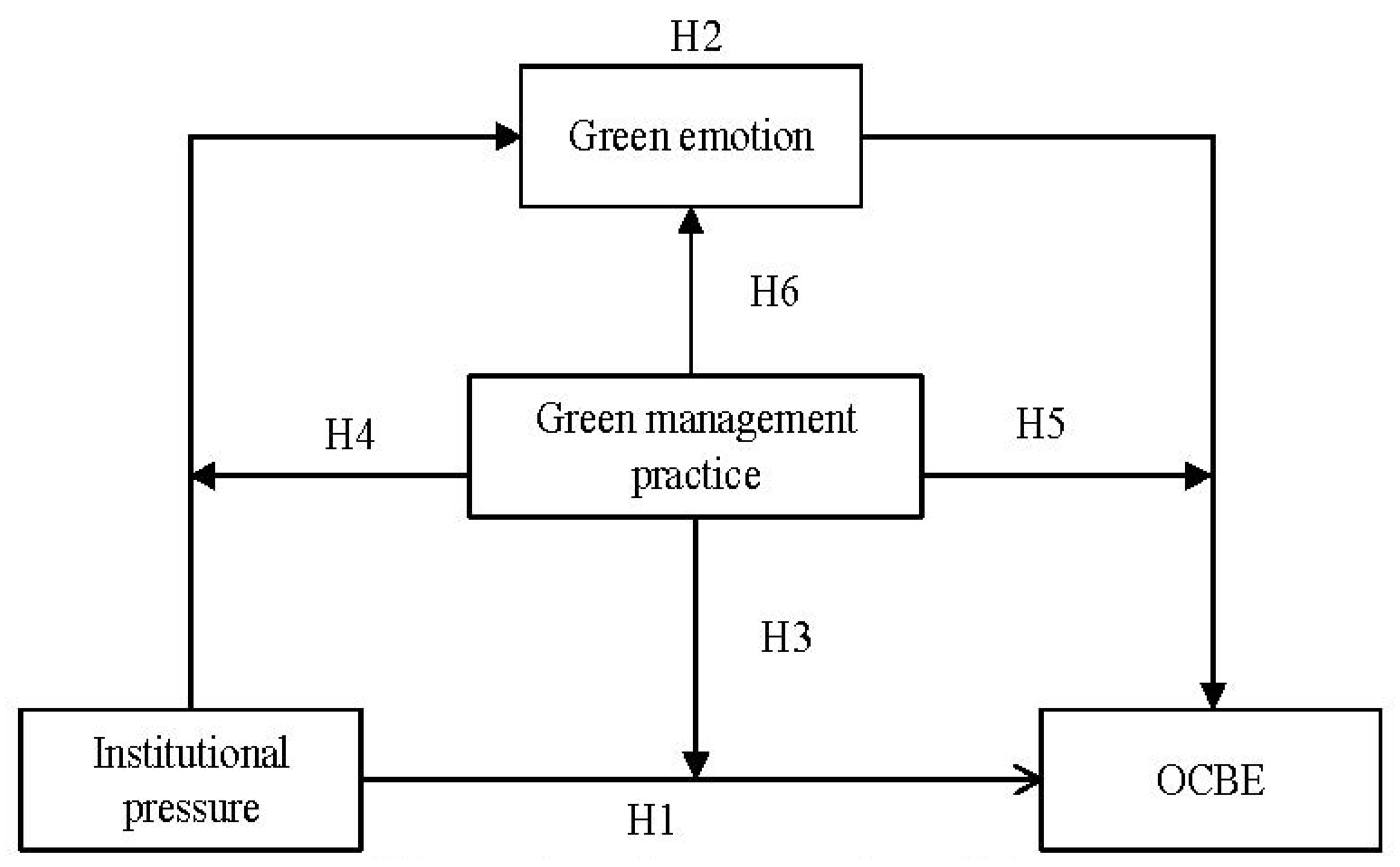

2.2. Institutional Pressure and OCBE

2.3. The Mediating Role of Green Emotion

2.4. The Moderating Role of Green Management Practice

2.5. The Moderated Mediation Model

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Institutional Pressure

3.2.2. Green Emotion

3.2.3. Green Management Practice

3.2.4. Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implantations

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire Items

| Construct | Measuring Items |

| Institutional pressure (IP) ([31]) | IP1 Our company’s products are subject to legal environmental protection regulations. |

| IP2 Our company’s products must comply with international environmental protection convention standards. | |

| IP3 Our company’s production is subject to international environmental standards. | |

| IP4 The government provides subsidies for companies to implement environmental protection measures. | |

| IP5 Government grants tax relief for companies implementing green measures. | |

| IP6 The government’s promotion of environmental protection has a positive impact on the company. | |

| IP7 Our company’s customers require products to meet environmental standards | |

| IP8 Our company’s customers value the green concept of products | |

| IP9 Our company establishes a good market image through the green products. | |

| IP10 Our company has a considerable market share through the green concept of our products. | |

| Green emotion (GE) ([82]) | GE1 It is important to me that the products I use don’t harm the environment. |

| GE2 I consider the potential environmental impact of my actions when making many of my consumption decisions. | |

| GE3 I am concerned about wasting the resources of our planet. | |

| GE4 I would describe myself as environmentally responsible. | |

| GE5 I am willing to be inconvenienced in order to take environmentally sustainable actions. | |

| Green management practice (GMP) ([51]) | GMP1 I proactively protect the environment, such as reducing pollution and carbon emissions. |

| GMP2 I take the initiative to eliminate harmful factors in the workplace. | |

| GMP3 I can use resources wisely and responsibly. | |

| GMP4 I consciously minimize raw material inputs. | |

| GMP5 I take the initiative to recycle my own products. | |

| GMP6 I respect the laws of nature. | |

| Organizational citizenship behavior for the environment (OCBE) ([8]) | OCBE1 I am a person who prints double-sided. |

| OCBE2 I am a person who uses a reusable coffee cup instead of a paper cup. | |

| OCBE3 I am a person who uses stairs instead of elevators between adjacent floors. | |

| OCBE4 I am a person who turns off lights when leaving my office for any reason. | |

| OCBE5 I am a person who powers down all desk electronics at the end of the day. | |

| OCBE6 I am a person who sets the air conditioner to a suitable temperature. | |

| OCBE7 I am a partner who works with other colleagues to improve the environmental sustainability of an organization. | |

| OCBE8 I am a person who advises superiors on ways to improve organizational environmental practices. | |

| OCBE9 I am a person who tries to help others learn how to improve the environmental sustainability of their organization. |

References

- Anwar, N.; Mahmood, N.; Yusliza, M. Green Human Resource Management for organisational citizenship behaviour towards the environment and environmental performance on a university campus. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Institutional pressures and environmental management practices: The moderating effects of environmental commitment and resource availability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugh, H.; Talwar, A. How do corporations embed sustainability across the organization. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2010, 9, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wang, J.; Yan, Z.; Xu, L.; Yin, G.; Chen, N. Robust vibration control for active suspension system of in-wheel-motor-driven electric vehicle via μ-synthesis methodology. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control. 2022, 144, 051007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B.; Bishop, J.; Govindarajulu, N. A conceptual model for organizational citizenship behavior directed toward the environment. Bus. Soc. 2009, 48, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisha, T.; Kathryn, M.; Laura, F. Motivating Employees towards Sustainable Behaviour. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 402–412. [Google Scholar]

- Lülfs, R.; Hahn, R. Corporate greening beyond formal programs, initiatives, and systems: A conceptual model for voluntary pro-environmental behavior of employees. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2013, 10, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, E.; Tosti-Kharas, I.; Williams, E. Read this article, but don’t print it organizational citizenship behavior toward the environment. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 163–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T. Building employee’s organizational citizenship behavior for the environment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 2019, 31, 406–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, A.; Stolberg, A. Explaining pro-environmental behavior with a cognitive theory of stress. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Corporate greening through ISO 14001: A rational myth. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, J. Does charismatic leadership encourage or suppress follower voice? The moderating role of challenge-hindrance stressors. Asian Bus. Manag. 2020, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L. Catalyzing employee OCBE in tour companies: The role of environmentally specific charismatic leadership and organizational justice for pro-environmental behaviors. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 682–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.; Zibarras, L.; Stride, C. Using the theory of planned behavior to explore environmental behavioral intentions in the workplace. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M. Do narcissistic employees remain silent? Examining the moderating roles of supervisor narcissism and traditionality in China. Asian Bus. Manag. 2021, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, N.; Bibi, Z.; Karim, J. Green human resource management practices and organizational citizenship behavior for environment: The Interactive Effects of Green Passion. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, G.; Sun, W.; Jia, J. Review and Prospects of Green Human Resource Management Research. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2015, 10, 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ardian, Q.; Zlatan, M.; Saranda, G. Green Supply Chain Management practice and Company Performance: A Meta-analysis approach. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 17, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm, E.; Tosti-Kharas, J.; King, C. Empowering employee sustainability, Perceived organizational support toward the environment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.; Taylor, S. Management commitment to the ecological environment and employees: Implications for employee attitudes and citizenship behaviors. Hum. Relat. 2015, 68, 1669–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, R.; Mawritz, M.; Mayer, D. To act out, to withdraw, or to constructively resist? Employee reactions to supervisor abuse of customers and the moderating role of employee moral identity. Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 925–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. Behavioural responses to climate change: Asymmetry of intentions and impacts. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N. Organisational sustainability policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, A.; Lee, K.; Hitigala, P. Institutional pressures, environmental management strategy, and organizational performance: The role of environmental management accounting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, C.; Jabbour, C.; de SousaJabbour, A.B.L.; Govindan, K.; Teixeira, A.A.; de SouzaFreitas, W.R. Environmental management and operational performance in automotive companies in Brazil: The role of human resource management and lean manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W. Approaching adulthood: The maturing of institutional theory. Theory Soc. 2008, 37, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Wong, C.; Cheng, T. Institutional isomorphism and the adoption of information technology for supply chain management. Comput. Ind. 2005, 57, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanalle, R.; Ganga, G.; Godinho Filho, M.; Lucato, W.C. Green supply chain management:an investigation of pressures, practices, and performance within the brazilian automotive supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Xie, Y.; Cooke, F.L. Unethical leadership and employee knowledge-hiding behavior in the Chinese context: A moderated, dual-pathway model. Asian Bus. Manag. 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, F. The relationship between institutional pressure, green environmental protection innovation practice and corporate performance—Based on the perspective of new institutionalism and ecological modernization theory. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2011, 29, 1884–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Dacin, M.; Goodstein, J.; Scott, W. Institutional theory and institutional change: Introduction to the special research forum. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A. Contrasting institutional and performance accounts of environment management systems. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 506–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M. The diffusion of environmental management standards in Europe and in the united states: An institutional perspective. Policy Sci. 2002, 35, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Du, J.; Chen, M. The influence mechanism of retail enterprises’ green cognition and green emotion on green behavior. China Soft Sci. 2013, 4, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Song, T.; Wu, S.; Jiang, L. An Empirical Study on the Influence of Green Advertising Requests on Purchasing Intention—Based on the Mediating Effect of Green Purchasing Emotion and the Moderating Effect of Self-Construction. Forecast 2020, 39, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wu, L. The impact of positive and negative emotion on green purchase behavior: Taking the purchase of energy-saving and environmentally friendly home appliances as an example. Consum. Econ. 2015, 31, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Dong, D.; Liu, R. The status quo and prospects of rational behavior theory and its extended research. Prog. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 16, 796–802. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Liang, J. High performance requirements and pro-organizational unethical behavior: Based on the perspective of social cognitive theory. Acta Psychol. 2017, 49, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinier, R.P., III; Laird, J.; Lewis, R. A computational unification of cognitive behavior and emotion. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2009, 10, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newton, J.; Tsarenko, Y.; Ferraro, C. Environmental concern and environmental purchase intentions: The mediating role of learning strategy. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1974–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, A.; Borchardt, M.; Vaccaro, G. Motivations for promoting the consumption of green products in an emerging country: Exploring attitudes of Brazilian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tamera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Estay, C. The formation mechanism of destructive leadership behavior: From the perspective of moral deconstruction process. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2022, 43, 750–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jing, F. Research on Low-Carbon Buying Behavior Model of Urban Residents—Based on Survey Data of Five Cities. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 22, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Wei, Z.; Su, Z. Frontier analysis and future prospects of green management research. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2010, 11, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mellahi, K.; Frynas, J.G.; Sun, P.; Siegel, D. A review of the nonmarket strategy literature: Toward multi-theoretical integration. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 143–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H.; Ahlstranb, W.; Lampel, J. Strategy Safari: A guided Tour through the Wilds of Strategic Management; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, P.; Thakkar, J. A review on supply chain performance measures and metrics: 2000–2011. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2012, 61, 518–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Institutional-based antecedents and performance outcomes of internal and external green supply chain management practice. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2013, 19, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, X. Strategic flexibility, green management, and firm competitiveness in an emerging. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proc. 2015, 101, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, C. An Empirical Study on the Influencing Factors and Green Performance of Green Cooperation among Enterprises. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2006, 5, 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Romani, S.; Grappis, S.; Bagozzi, R. Corporate socially responsible initiatives and their effects on consumption of green products. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R. The Redundant Resources of Enterprises and the Source of Bounded Rationality. Econ. Surv. 2004, 4, 92–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Shen, A. Research on the relationship between unabsorbed redundancy, green management practice and corporate performance. Chin. J. Manag. 2018, 15, 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Ho, Y. Determinants of Green Practice Adoption for Logistics Companies in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, R. Adopting sustainable innovation: What makes consumers sign up to green electricity. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, J. Context, Comparison, and Methodology in Chinese Management Research. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2009, 5, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galpin, T.; Whittington, J. Sustainability leadership: From strategy to results. J. Bus. Strategy 2012, 33, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; He, Q.; Yang, D.; Yan, X.; Yu, T. Institutional Pressure, Environmental Citizenship Behavior and Environmental Management Performance: An Empirical Study Based on China’s Major Projects. J. Syst. Manag. 2018, 27, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Negash, M.; Lemma, T. Institutional pressures and the accounting and reporting of environmental liabilities. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1941–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Talbot, D.; Paille, P. Leading by example: A model of organizational citizenship behavior for the environment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lu, C.; Jiang, G.; Wang, Y. The influence of political promotion of state-owned enterprise executives on corporate mergers and acquisitions: An empirical study based on the theory of corporate growth pressure. Manag. World 2015, 9, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, A.S. Determinants of top-down knowledge hiding in firms: An individual-level perspective. Asian Bus. Manag. 2021, 20, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Lei, X.; Chen, L.; Li, Y. Research on the Relationship between Green Environmental Protection Pressure and Enterprise Reverse Logistics Performance. Manag. Sci. 2008, 5, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Qin, Q.; Lin, Y. The Cognitive Mechanism of Consumers’ Purchase Decisions in Fake Promotions: An Empirical Study Based on Time Pressure and Overconfidence. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Analysis on the Application of Cognitive Behavior Theory in Social Work Practice. Popul. Soc.·Leg. Stud. 2011, 8, 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Jin, S.; Sun, R. An overview of life history theory and its integration with social psychology: Taking moral behavior as an example. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 24, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, J.; O’connor, M. Environmental Education and Attitudes: Emotion and Beliefs are What is Needed. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. The Influence of Resource Conservation Consciousness on Resource Conservation Behavior—A Model of Interactive and Moderating Effects in the Chinese Cultural Context. Manag. World 2013, 8, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, R. The Mechanism of the Influence of Psychological Factors on Consumers’ Ecological Civilization Behavior. J. Manag. 2011, 8, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K.; Lepak, D.; Hu, J. How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1264–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q. Research on the Relationship between Institutional Pressure, Green Supply Chain Management practice and Enterprise Performance. J. Wuhan Text. Univ. 2019, 32, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, J.; Ramstad, P. Talentship, talent segmentation, and sustainability, a new HR decision science paradigm for a new strategy definition. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, G. Research on the Impact Mechanism of Green Human Resource Management Practice on Employees’ Green Behavior—Based on the Perspective of Self-Determination Theory. China Hum. Resour. Dev. 2018, 35, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Wu, Z. How to facilitate employees’ green behavior? The joint role of green human resource management practice and green transformational leadership. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 906869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zou, J.; Chen, H. Promotion or inhibition? Moral norms, anticipated emotion and employee’s pro-environmental behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, F.; Md Rami, A.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z. Effects of emotions and ethics on pro-environmental behavior of university employees: A model based on the theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Zhou, K.; Xiao, Y. How Green Management Influences Product Innovation in China: The Role of Institutional Benefits. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.; Rucker, D.; Hayes, A. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory Methods and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Leveraging factors for sustained green consumption behavior based on consumption value perceptions: Testing the structural model. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 95, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.; Marans, R. Towards a campus culture of environmental sustainability: Recommendations for a large university. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2012, 13, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Nd, R. The self-importance of moral identity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 (df) | ∆χ2(∆df) | CFI | TLI | IFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-factor model | IP, GE, GMP, OCBE | 422.63 (353) ** | - | 0.955 | 0.945 | 0.957 | 0.044 |

| 3-factor model | IP, GE + GMP, OCBE | 499.38 (355) ** | 76.75 (2) ** | 0.907 | 0.886 | 0.912 | 0.063 |

| 3-factor model | IP + OCBE, GE, GMP | 495.95 (355) ** | 73.32 (2) ** | 0.914 | 0.889 | 0.909 | 0.062 |

| 2-factor model | IP + OCBE, GE + GMP | 551.26 (354) ** | 128.63 (1) ** | 0.873 | 0.844 | 0.879 | 0.074 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Gender | 1.69 | 0.46 | 1 | |||||||

| 2.Age | 2.33 | 0.79 | −0.08 | 1 | ||||||

| 3.Education | 1.97 | 0.55 | −0.09 | −0.59 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4.Industry | 5.23 | 2.43 | −0.04 | −0.17 * | 0.02 | 1 | ||||

| 5.Length of service | 1.97 | 1.26 | −0.14 * | 0.84 ** | −0.52 ** | −0.14 | 1 | |||

| 6.IP | 3.93 | 0.66 | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.09 | −0.14 * | 0.06 | 1 | ||

| 7.GE | 3.89 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.10 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.42 ** | 1 | |

| 8.GMP | 3.87 | 0.61 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.46 ** | 0.18 * | 1 |

| 9.OCBE | 3.92 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.17 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.04 | 0.22 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.48 ** |

| Variables | Model 1 (Criterion: GE) | Model 2 (Criterion: OCBE) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | se | t | p | β | se | t | p | |

| Constant | −0.08 | 0.63 | −0.13 | 0.90 | −0.43 | 0.54 | −0.80 | 0.43 |

| Gender | −0.09 | 0.14 | −0.68 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.95 |

| Age | 0.16 | 0.16 | 1.04 | 0.30 | −0.01 | 0.14 | −0.08 | 0.94 |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Industry | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.35 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.59 |

| Length of service | −0.11 | 0.09 | −1.13 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 1.63 | 0.11 |

| IP | 0.55 | 0.08 | 6.77 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 4.24 | 0.00 |

| GE | 0.14 | 0.07 | 2.06 | 0.04 | ||||

| GMP | −0.13 | 0.08 | −1.65 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 2.64 | 0.01 |

| GMP × IP | 0.21 | 0.06 | 3.55 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 3.57 | 0.00 |

| GMP × GE | 0.13 | 0.06 | 2.23 | 0.03 | ||||

| R2 | 0.23 | 0.44 | ||||||

| F | 7.39 *** | 15.17 *** | ||||||

| Types | Index | Effect | BootSE | Boot 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||

| Moderated mediation | Eff1 (GMP = M − 1SD) | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.16 |

| Eff1 (GMP = M) | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.20 | |

| Eff1 (GMP = M + 1SD) | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.38 | |

| Moderated mediation effect comparison | Eff2-Eff1 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.15 |

| Eff3-Eff1 | 0.20 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.40 | |

| Eff3-Eff2 | 0.13 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.27 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, C. How Institutional Pressure Affects Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: The Moderated Mediation Effect of Green Management Practice. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912086

Wu M, Zhang L, Li W, Zhang C. How Institutional Pressure Affects Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: The Moderated Mediation Effect of Green Management Practice. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912086

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Mengying, Lei Zhang, Wei Li, and Chi Zhang. 2022. "How Institutional Pressure Affects Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: The Moderated Mediation Effect of Green Management Practice" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912086