1. Introduction

Since the announcement of the 2020 ‘double carbon’ goal, which refers to China’s carbon peaking in 2030 and carbon neutrality in 2060, Chinese consumers have become increasingly concerned about climate change and sustainability, and the green economy is growing in size. More and more companies are realising that transparency in corporate governance and quality management are prerequisites for healthy business development [

1], and, therefore, more and more companies are inclined to invest capital in green innovation and green marketing and increasing tendencies toward strategies related to decarbonisation and clean energy [

2,

3]. However, due to the information gap between companies and consumers, some companies are turning to more ‘economical’ greenwashing to make them appear environmentally friendly [

4] and to increase consumer trust [

5] while paying less for environmental protection and, thus, gaining financial benefits [

6,

7]. This has led to a greater preference for greenwashing in corporate social responsibility and growing consumer scepticism about companies’ green claims [

8]. Greenwashing is used to describe corporate behaviour that makes misleading statements about the green attributes of its brands or products, as opposed to genuine environmental behaviour [

9]. These companies either over-glamorise corporate environmental responsibility [

10], conceal information about environmentally responsible behaviour or even fabricate untrue environmentally responsible behaviour [

11]. These tactics cause consumers who are inclined to buy environmentally friendly brands or products to develop a preference for such products and purchase them.

At the consumer level, corporate greenwashing negatively affects consumers’ willingness to buy green through green word-of-mouth [

12]. At the enterprise level, the proliferation of greenwashing can cause greenwashing in companies up and down the supply chain due to the ‘ripple effect’ between companies, which can be a serious impediment to sustainable socio-economic development [

13]. At the social level, the greenwashing behaviour of companies will cause consumers to doubt the green philosophy of the brand and create a sense of distrust [

11], which in turn will lead to social trust and moral crisis, shake the whole society’s awareness of environmental protection, increase the transaction costs of the whole society, reduce the efficiency of transactions, and impact on the overall ecological civilisation [

14]. Therefore, further exploration of the impact mechanisms of greenwashing is of great value to both corporate performance and the social environment.

In recent years, scholars have shown great interest in the field of corporate greenwashing and have focused on the causes [

6,

15], hazards [

16,

17,

18], and governance of greenwashing [

19,

20,

21]. In relation to the dangers of corporate greenwashing, studies have verified the negative impact of consumers’ greenwashing perception on their green purchasing intentions. The intermediate mechanisms of consumer greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions have also been explored from the perspectives of green brand loyalty, green brand image [

17], and green word of mouth [

12]. However, the vast majority of these studies have been conducted from the perspective of enterprises to explore the negative effects of greenwashing, and relatively few studies have been conducted on the intermediate mechanisms of psychological changes in individual consumers. On the one hand, it is important to understand the psychological changes in individual consumers’ greenwashing perception, which can help enterprises to reduce the losses caused by greenwashing behaviour and save their economic performance and brand equity loss; on the other hand, it is valuable for the relevant government departments to implement targeted measures to resolve consumers’ green consumption trust and moral crisis. To enrich the relevant research, this paper extends the study of greenwashing to the field of psychology, based on the classic theory of psychological contract, and introduces the perceived betrayal into the study of the influence of consumers’ greenwashing perception on their green purchasing intentions.

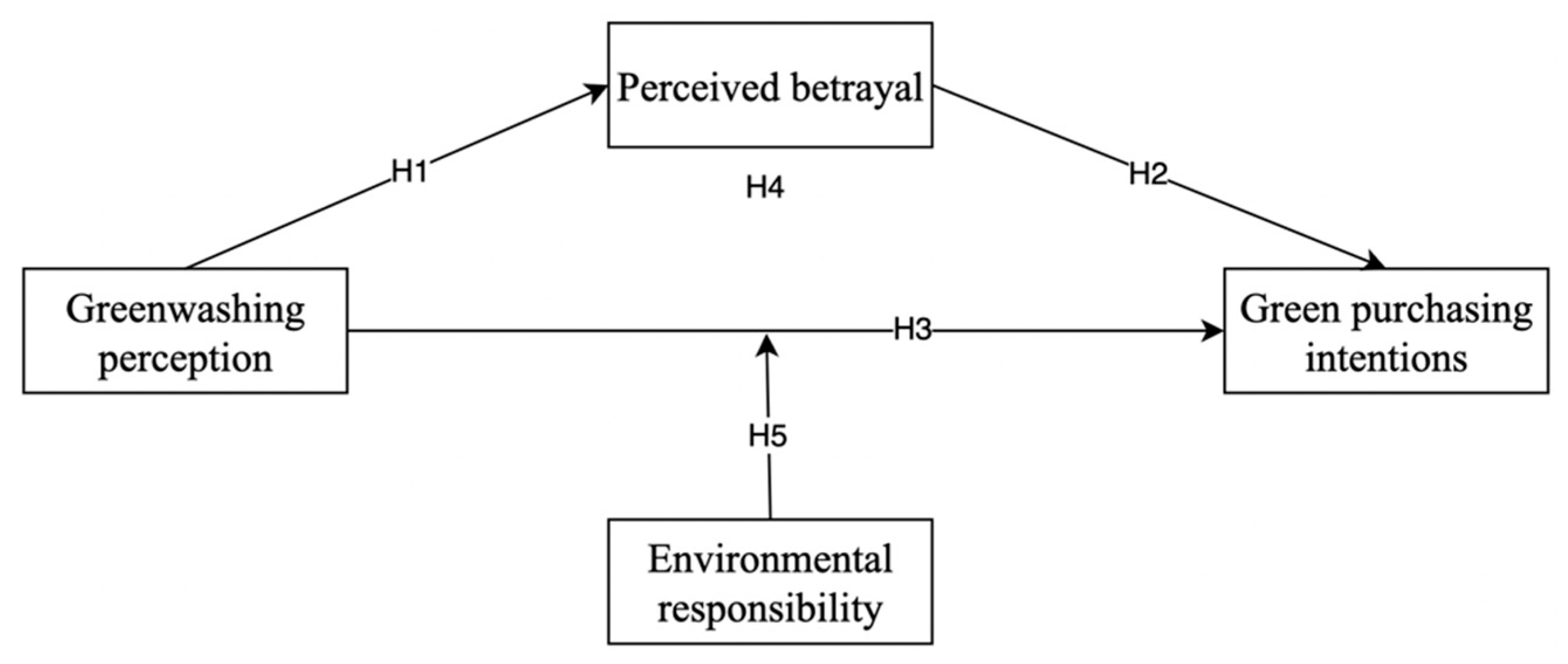

This paper establishes a new framework for the relationship between greenwashing perception and green purchasing intentions, verifies the negative relationship between consumers’ greenwashing perception and green purchasing intentions, and incorporates perceived betrayal and environmental responsibility into the study. At the same time, this paper introduces the psychological contract theory into the field of green marketing, further validating the explanatory logic of the psychological contract theory and, thus, helping companies to alleviate consumers’ withdrawal behaviour from green purchases due to greenwashing perception in a more systematic and targeted manner.

This paper has the following new contributions: First, this paper develops the explanatory logic of psychological contract theory by applying it to the study of consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing and elucidates the process of consumers’ psychological reactions to perceived corporate greenwashing behaviour. Secondly, this paper introduces perceived betrayal into the influence relationship of consumers’ greenwashing perception on their green purchasing intentions, enriching the study of the individual psychological mechanisms in this influence relationship and opening the black box between consumers’ greenwashing perception and their green purchasing intentions. Thirdly, this paper introduces environmental responsibility and verifies the moderating influence of environmental responsibility on the mediating role of perceived betrayal

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

The relationship between greenwashing perception and green purchasing intentions has mostly been studied at the firm level [

18], but less attention has been paid to the psychological change mechanisms of consumers after exposure to firms’ greening behaviour [

61]. Therefore, this paper focuses on the psychological mechanisms when consumers perceive a company’s greening behaviour and explores the role of perceived betrayal and environmental responsibility in the influence of greenwashing perception on their green purchasing intentions. Based on psychological contract theory, this paper constructs a moderated mediation model in which greenwashing perception act on green purchasing intentions and regression analysis of the collected questionnaire data was conducted, and the empirical study found that: firstly, greenwashing perception has a significant negative effect on consumers’ green purchasing intentions. The higher the degree of greenwashing perception, the lower the green purchasing intentions. Secondly, perceived betrayal plays a partially mediating role in the effect of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions. Consumers’ reduced willingness to buy green is often due to their perception that the company has betrayed their psychological contract after they have perceived the company’s greenwashing behaviour. Thirdly, environmental responsibility plays a moderating role in the effect of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions. The more concerned consumers are about the environment and the more committed they are to protecting it, the more likely they are to reduce their willingness to buy green because of perceived corporate greenwashing behaviour. Fourthly, consumers’ environmental responsibility moderates the mediating role of perceived betrayal in the relationship between greenwashing perception and green purchasing intentions. The stronger the consumer’s environmental responsibility, the more likely greenwashing perception influences consumers’ green purchasing intentions through perceived betrayal rather than directly.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

Firstly, this paper develops psychological contract theory by applying it to the study of consumers’ greenwashing perception and verifying the moderating influence of environmental responsibility on the mediating role of perceived betrayal. Psychological contract theory is the belief that the non-fulfilment of commitments by one of the reciprocating parties will result in a psychological contract breach and hence withdrawal behaviour [

29]. This paper verifies through empirical analysis that this relationship can be influenced by the consumer’s subjective psychological evaluation (i.e., environmental responsibility in this paper) of that commitment. This study treats the greenwashing perception as the motivating event of psychological contract breach and considers the effect of perceived betrayal on green purchasing intentions as the result of psychological contract breach. This paper elucidates the process of consumers’ psychological responses to perceived corporate greenwashing behaviour and develops the explanatory logic of psychological contract theory.

Secondly, this paper introduces the perceived betrayal into the process of consumers’ greenwashing perception of their green purchasing intentions. It enriches the study of the mechanisms of individual consumer psychological effects after consumers perceive corporate greenwashing behaviour and provide a new perspective for exploring the factors influencing consumers’ green purchasing intentions. Mistrust is the main factor influencing consumers’ active choice of green products [

44]. This paper focuses its research horizon on the individual psychological mechanism of action after consumers perceive a company’s greenwashing behaviour [

31,

61] rather than at the company level [

5,

18] and provides theoretical support to alleviate the negative evaluation and withdrawal behaviour of consumers due to the greenwash behaviour of companies at the root.

Finally, the paper introduces the sense of environmental responsibility to verify the moderating role of environmental responsibility in the relationship between greenwashing perception and green purchasing intentions and confirms that consumers with different levels of environmental responsibility have different degrees of influence on their green purchasing intentions when they perceive greenwashing behaviour [

44]. The negative effect of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions is negatively moderated by consumers’ environmental responsibility [

56], i.e., the stronger the consumer’s environmental responsibility, the stronger the effect of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions, and the weaker the opposite.

5.3. Managerial Implications

Firstly, consumers’ greenwashing perception negatively influences consumers’ green purchasing intentions, and companies should fulfil their environmental commitments and disclose details in a timely manner. With the advent of the self-media era, the information gap between companies and consumers is becoming smaller and smaller, and the possibility of companies taking advantage of the information gap to speculate for financial gain is diminishing. Managers should recognise that greenwashing can bring short-term benefits but is not sustainable. Therefore, companies should reduce the incidence of greenwashing and take a pragmatic approach to corporate environmental responsibility.

Secondly, perceived betrayal partially mediates the negative relationship between greenwashing perception and green purchasing intentions. Therefore, to reduce economic losses and restore corporate image, companies should take timely measures to mitigate the perceived betrayal after consumers perceive the company’s greening behaviour, such as introducing third-party organisations or the general public to monitor the company, and promptly announcing details of its environmental practices, to reduce the stigma in consumers’ minds and, thus, reduce the impact on the company’s performance.

Finally, environmental responsibility plays a moderating role in the negative impact of perceived betrayal and greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions. This means that consumers with higher environmental responsibility have weaker green purchasing intentions when they perceive a company’s greenwashing behaviour, which also means that the stronger the consumer’s environmental responsibility, the greater the cost of a company’s greenwashing behaviour after being perceived by the consumer. Therefore, to combat corporate greenwashing, the government and NGOs should step up their efforts to promote environmental protection, arouse public concern for the environment, and raise consumers’ sense of environmental responsibility.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study is limited to the effect of consumers ‘greenwashing perception on their green purchasing intentions after they perceive that the company is greenwashing. Future research could extend the scope of the study to include the impact of consumers’ greenwashing perception on the green purchasing intentions of other companies or products in the industry or even on consumers’ overall willingness to consume green. Secondly, in this paper, the questionnaire was distributed to consumers, and all variables were measured in the same period, which has certain limitations in the verification of the causal and moderating relationships of each variable, and future research could consider the form of an experimental method for measurement. Finally, future research could expand the research perspective to compare different cultures in different countries and could divide people into different groups, such as the sensitive type and the tonal type, to study the different effects of the perception of bleached green on the willingness to buy green and the perceived betrayal.