1. Introduction

Food security has become one of the most pressing issues of the present day. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has reported that over the past 6 years, food security has increased in severity across the globe, and affected thirty percent of the world’s population [

1]. The situation is likely to deteriorate even further, given the adverse ramifications of food scarcity in recent years, including a record high input price/Global Input Price Index (GIPI) value in 2021 and an all-time high global import bill in 2022 [

2]. In the past two years, the COVID-19 pandemic also revealed or intensified vulnerabilities in the global food production and supply chain. Other major challenges are also caused by rising input costs, the ongoing war in Ukraine [

2], and stagnant productivity growth owing to inadequate investment in research and development for agricultural technology [

3].

Another factor exacerbating the problem of food insecurity is climate change, which has effects at both the industry and household levels [

4]. The FAO noted that more countries are beginning to experience climate extremes, with casualties rising from 76% of low- and middle-income countries in 2000–2004 to 98% in 2015–2020 [

1]. On a more granular level, Niles and Salerno [

5] found that 71% of households surveyed across several continents had felt the effects of climate shocks in the preceding five years, and 54% experienced food insecurity for at least one month annually. Lee, Nadolnyak, & Hartarska [

6] also found that higher temperatures during the fall season are detrimental to agricultural activities in South and Southeast Asia, while the overall rise in annual temperatures has depleted crops in Asian countries. The effects are also predicted to persist in the upcoming decades. For example, in Tanzania, the current rate of climate change is expected to reduce average agricultural production by more than 10% [

7].

While climate change affects food production, food consumption contributes to climate change and environmental degradation, and its impact is expected to grow given the growing global population [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Transitioning towards more sustainable food consumption, therefore, is becoming more and more important [

12,

13,

14]. Although it has been widely studied, the definition of sustainable food consumption has not yet been universally agreed upon. The UK Sustainable Development Commission [

15] defines sustainable food as healthy, safe, and hygienic produce which is able to meet global needs, provides viable livelihood for farmers, processors, and retailers, supports rural economics, and respects biophysical and environmental limits, all the while reducing energy consumption and improving the wider environment; respects the highest standards of animal health and welfare compatible with the production of affordable food for all societal sectors; and supports rural economies and the diversity of rural culture, in particular by emphasizing local products that keep food miles to a minimum.

As the decision-making process of sustainable food consumption is complex, a wide range of potential determinants has been studied and identified to understand it better. For example, the level of income is found to be an important factor that influences sustainable food consumption preference [

11,

16]. Thøgersen also reports that sustainable food consumption is impacted by food-related lifestyle, which depends on the country of residence [

11]. These differences in sustainable consumption across countries are the reasons why a single factor cannot explain the variance observed in sustainable consumption [

17]. This suggests that understanding the factors influencing sustainable food consumption requires careful consideration of country-specific contexts.

In Singapore, food scarcity is also considered an imminent possibility. Despite ranking very high in the food availability and affordability criteria in the Global Food Security Index 2021, the country is facing potential instability from exposure to climate risks [

18]. Importantly, Singapore sources most of its food supply from overseas, while local food production contributes to a mere 10% of the total consumption [

19].

In response, the Singapore government has acknowledged the need to pursue a more sustainable food supply chain to ensure the country’s food security. According to the Green Plan 2030, Singapore has set a target to increase domestic food production such that it sustains at least 30 percent of locals’ nutritional needs by 2030. This plan is termed “30 by 30”. The country aims to achieve this goal by optimising its use of technology, and investing in research and development on “sustainable urban food production” [

20]. First, to tackle the challenge of land scarcity, which has impeded the city’s capability to grow local produce on a large scale, Singapore has utilized various technologies such as vertical farming, aquaculture, and aquaponics, which is a combination of hydroponic farming and aquaculture [

21]. Second, a number of farms have adopted information and communication technology (ICT) in the farming management, such as Internet of Things (IoT), cloud computing, and smart systems to improve their operations and make them more efficient. Third, several farms have adopted or invested in renewable sources of energy, such as solar panels for powering up the farm and electric vehicles for transporting the produce [

22].

Singapore also granted more licenses to operate food farms, leading to the increase in number of local food farms from 221 in 2019 to 260 in 2021, consisting of 150 land-based farms and 110 sea-based farms [

19,

23]. The licenses granted by the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) are to ensure that each farm has a secure plan and premise in place and meets the benchmark/minimum safety and sanitary conditions [

24]. The increase in the number of licensed farms has led to a 13% increase in total production value of eggs, vegetables, and seafood, from SGD (Singapore dollar) 163.4 million (equivalent to USD 119.3 million) in 2020 to SGD 185.2 million (USD 135.2 million) in 2021 [

19]. The country has also seen a steady growth in the production of hen shell eggs, with the quantum rising from 528.1 million in 2019 to 643.7 million in 2021 [

19]. Hen shell eggs are currently the highest consumed local produce, contributing to nearly one-third of the total egg consumption in 2021. However, consumption of other local produce also needs to be encouraged further, as local vegetables and seafoods approximately contribute merely 4% and 7–8% to the total consumption, respectively [

19]. Moreover, local production of vegetables and seafoods had taken a decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, resulting in lower supply of local produce [

19]. It is reported that the price of local produce is higher by between 10 to 20% compared to produce from other regions, such as Malaysia [

25], thereby potentially making local produce less attractive in the eyes of the average consumer.

Besides low market demand, another problem threatening the survival of local farms in Singapore is immense competition face by producers to secure contracts with large supermarket companies to distribute their products efficiently. This is important especially for small scale farmers as it allows them to keep the distribution costs low. Additionally, major food retailers such as NTUC Fairprice, Dairy Farm International, and Sheng Siong account for more than 50% of Singapore’s market share [

26]. However, competition for agricultural products in Singapore market is becoming more intense [

26], providing barriers for local farms to enter the market, which may lead to a majority of local farms facing higher than desired distribution costs.

In order to boost demand for local produce, the Singapore government, through the Singapore Food Agency (SFA), has set up several policies and programs targeted at both producers and consumers. For producers, the SFA has allocated a total of SGD 144 million to improve research and development (R&D) in sustainable food production, innovation, and safety [

19]. The policy aims to enable industries to increase productivity and cost efficiency.

Beyond supply side policies, there is scope for the government to introduce demand management policies that encourage locals to shift their consumption preferences from imported foods to local produce. In 2020, the SFA set up a Singapore Food Story campaign, which was publicised through various media outlets, including government websites and social media platforms. Additionally, the SFA designed a set of logos to help buyers recognize local produce. The logos have since been printed on the packaging of local produce. The designs include: a 1-star badge to identify locally grown fresh produce; a 2-star badge to identify fresh produce from farms which adhere to Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) standard; and a 3-star badge to identify fresh produce which are quality assured and sustainably grown [

27]. The government has also partnered with the Singapore Agro-Food Enterprises Federation Limited (SAFEF) in organising the ‘SG Farmers’ Market’ at various community spaces and online platform, such as Lazada and Redmart which are common online shopping site in Singapore [

28]. This alternative market allows consumers to easily purchase local produce both through offline and online platforms.

In Singapore, locally grown food has also been contextualized as an environmentally sustainable food option, as it is associated with environmentally sustainable food chain. In fact, purchasing locally produced products can be a way to become more environmentally sustainable [

29], as producing locally reduces the amount of greenhouse gas emissions emitted from transportation and the water and land use in the farming process [

30,

31]. A survey by the National Climate Change Secretariat (NCCS), Prime Minister’s Office shows that more than 90% of Singapore residents have awareness of climate change and its impact, while nearly 80% are willing to take action to fight climate change. At the same time, a study shows that while 88% of Singaporeans know that buying locally grown food is more eco-friendly, only 14% purchase products that are sourced locally or within the Southeast Asia region every time they shop [

25]. Why do consumers have a favourable attitude towards sustainability and an intention to consume sustainable food, yet it does not translate into action? This attitude–behaviour, or, intention–behaviour gap can be caused by various factors. One potential reason is information deficit, with only 65% of consumers being able to determine whether a product was locally produced [

32]. A number of studies investigate these gaps with respect to sustainable food consumption and find factors such as wealth level, price, environmental view, availability, and convenience as other potential reasons [

10,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

With regard to locally produced food, numerous studies have been carried out to understand the consumer decision-making patterns. Feldmann and Hamm [

39] conducted a literature review for the topic and found 550 scientific articles between January 2000 and January 2014. However, they foreground that there is no universally accepted definition for ‘local’, because many of the articles reviewed used different criteria for determining whether food products qualified as ‘local’, such as proximity or distance, emotional and social context, and political boundaries (states, provinces, or countries). For the context of this paper, ‘local food’ is defined as food products which are produced within the country.

The findings regarding the influence of environmental view on local food purchase is mixed. While Yue and Tong [

40] find it to be an importance factor affecting purchase decision, Zepeda and Li [

41] report that it does not affect the actual purchase. In some areas which are known to have strong agricultural prominence, consumers tend to favour local production as the produce are perceived to have higher quality, as well as better freshness and taste [

40,

42,

43,

44]. Furthermore, consumers’ perception on local foods’ quasipublic elements, such as the product’s contribution to the local economy and the environment, have proven to be a determinant of consumption decisions [

45,

46,

47,

48]. However, many studies affirmed that despite large support for local produce, accessibility and price also play a part in shaping consumer preferences [

48]. Adams and Adams [

42], for instance, conducted a cluster analysis in their study and suggested that consumers’ motivation for purchasing local foods is a dynamic interaction between their perceptions about the food system, socioeconomic characteristics of the consumers, and the ease of accessibility of the local foods.

Some researchers have also dig deeper to understand consumers’ preference toward local produce by investigating their premiums and willingness to pay (WTP). Gaining insights about consumers’ WTP for local food can provide policymakers with useful knowledge to devise and implement policies to promote such products [

49]. Printezis et al. [

49] reviewed research papers on consumers’ WTP for local food and the number of such studies to be increasing since early 2020s as the shift toward local foods became noticeable. Most of these studies show that consumers are willing to pay for the “local” attribute of varieties of food items in different countries [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56] although Printezis et al. [

49] point out that it may be overestimated due to publication selection bias.

People’s willingness to pay for local produce has been attributed to multiple factors, ranging from individuals’ lifestyles and consumption habits, such as cooking frequency and attention to nutritional value [

57]; perceptions of product quality, including taste, freshness, and nutrition; perception of the products’ quasipublic factors [

45,

58]; accessibility and affordability [

48]; income [

50,

51,

59,

60]; gender [

47,

60,

61], environmental concern as well as education [

60]. On the other hand, age was not found to influence willingness to pay for local produce [

47,

50,

61].

Fan, Gómez, & Coles [

36] found in the case of California that if a product contains information that it is locally produced, there will be an increase in consumers’ WTP for that product and their judgment regarding the product’s quality would be more positive. In a survey conducted by Profeta & Hamm [

62] amongst German consumers, it was reported that 60% of the subjects exhibited a higher WTP for local animal products if the animals consumed local feed during the rearing process. Another study conducted in South Carolina, United States, showed that consumers are willing to pay an average premium of 27% for local produce and 23% for local animal products [

47]. However, a contradictory result was also found by Brown [

60] from a study conducted in Missouri, United States, where only one-fifth of the consumers expressed their WTP at a premium of at least 5% for locally grown foods.

Despite recent efforts to increase the demand for local produce in Singapore, research on Singaporean consumers’ local produce purchasing behaviour is non-existent. The current study aims to understand the demand for local produce in Singapore by conducting a survey to local consumers. Based on the findings by existing literature, the analysis includes various factors influencing consumers’ purchase behaviour: consumers’ perception of environmental issues; economic factors (price, household income level); practical factors (accessibility, availability, quality); accessibility (easiness to identify); as well as other household socioeconomic attributes. One additional factor this study considers is consumers’ willingness to support the local farmers/the country’s food security objective. This is relevant in Singapore context, as the local produce is promoted as something Singaporeans should be proud of, and is regarded as a means to ensure food security. Further, the survey asks the consumers about their WTP for the local produce, which enables additional analysis to gain insights that are useful for marketing local produce.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Sustainable food consumption has become a critical issue today under the pressure of population growth and climate change. In Singapore, food security is threatened by these factors particularly due to its low food self-sufficiency, and this is also why the Singapore government now aims to enhance local production dramatically. This study attempted to better understand the demand for local produce in Singapore by investigating the factors influencing the purchasing decisions of local consumers, as well as their willingness to pay a premium for locally produced eggs, vegetables, and seafood in Singapore. Understanding what drives consumer demand for local produce is crucial for designing future policies targeted at achieving the “30 by 30” goal. The findings of this study can inform policymakers and businesses on what specific markets for local food they can direct their efforts at developing, as well as what marketing strategies they can adopt to better appeal to local consumers.

An online survey was conducted, with questions focusing on identifying consumers’ socioeconomic characteristics, their perceptions and actions with regard to environmental issues, their purchasing behaviour with regard to local produce, and their willingness to pay a premium for it vis à vis their imported counterparts. Responses from 400 participants were analysed to investigate the factors influencing consumers’ purchasing decisions and their willingness to pay a premium for local foods.

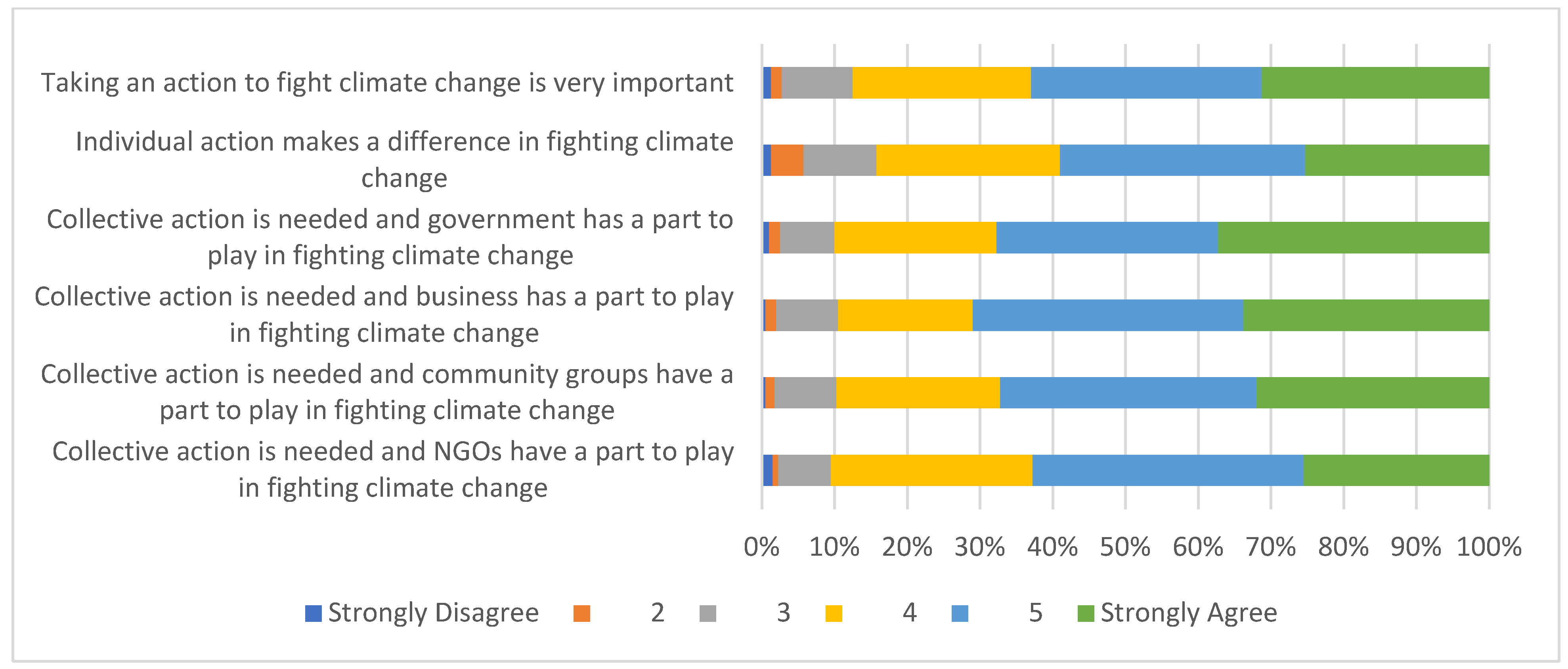

First, it was confirmed that extremely high proportion (nearly 90%) of consumers believe that it is important to make a shift towards a low-carbon economy as well as to make actions to fight climate change, which is consistent with the findings of the survey conducted by The National Climate Change Secretariat (NCCS). This suggests that the estimation results will shed light on the causes for attitude/intention–behaviour gap where people have positive attitude regarding sustainability or intention to purchase local food, but it does not translate into action.

The estimation results for purchasing local produce showed that environmental attitudes or behaviour traits are not the main drivers for demand for local produce despite the high proportion of the population with pro-environmental views. This finding is similar to the study by Zepeda and Li [

41] reporting that environmental attitudes do not affect the actual purchase.

Instead, what was found to influence local produce purchase were product-specific factors, such as its quality, freshness, and easiness to identify at the store show, which corroborates previous studies [

40,

42,

43,

44] conducted in other countries. Some of the ways the policymakers and businesses could leverage on this finding to enhance the demand could be via: (i) ensuring appropriate packaging by the producer by adding origin labels; (ii) placing advertisements at the store to make it easy to identify the local produce, and (iii) promotion by the government through awareness campaigns to highlight the high quality of local produce.

Similarly, our analysis also showed that support for local farmers/Singapore’s food security has a strong and positive impact on the purchase decisions on local vegetable, which is supported by the finding by Yue and Tong [

40] that report support for local economy promoted local produce purchase. This could be because of greater awareness and exposure, as consumers can readily access information pertaining to local vegetable farmers via food blogs and similar websites in Singapore. Extending this argument, policymakers and businesses may be able to reap similar results in the other categories as well, by making local egg and fish producers more visible to consumers and thus potentially motivating them to support local producers.

Household size, nationality, ethnicity, and whether they cook for children under 12 years old were also found to be associated with purchase, though only for fish.

As for the willingness to pay (WTP) for local produce, more than half of the surveyed consumers were willing to pay higher price for local produce compared to the imported. Overall, the results pertaining to the WTP for local produce suggest that environmental perception and behaviour do positively affect consumers’ WTP, which confirms findings by Brown’s [

60] that consumers with higher environmental concerns are willing to pay more for local products. Income level also showed a strong positive association with WTP, which corroborates findings by a number of studies [

50,

51,

59,

60]. Though age was not found to be a determinant of willingness to pay in previous studies [

47,

50,

61], this study identified younger consumers to have higher WTP. Pro-environmental views and behaviour were found to influence WTP more than they influence purchase decision.

In light of the aforementioned results, it is suggested that what is primarily hindering the local produce demand of consumers with positive perceptions towards sustainability is not their income or product price. Rather, what is important in their purchase decisions seems to be product-specific factors, such as freshness and quality, as well as easiness to identify the product at store. Ensuring these factors can potentially lead to higher demand for local produce in Singapore. Support for local framers and Singapore’s food security was also found to be a driver for the purchase. Promoting and emphasizing the link between local produce and these can motivate the consumers to purchase local produce more often.

Meanwhile, attitudes and behavioural traits related to sustainability played a larger role in WTP than in purchase decision-making. This implies that if local produce prices are set higher than their imported counterparts, then it is pertinent that the policymakers and businesses invest in ensuring that the consumers understand the potential pro-environmental contributions of such a decision.

In addition, this study highlights the importance of understanding the demand for different varieties of local produce to better inform producers and policymakers in designing the associated campaigns and marketing, as our analysis reveals that factors influencing their purchase decision and WTP vary by food category.

One major limitation of this study is the representativeness of the study sample. First, recruitment was based on limited panels registered with a survey company. Second, the selection was not random, which may have resulted in participants with higher interest in local produce in Singapore. Third, the sample size is not large (400). Therefore, the findings of this study are specific to those who participated in this study though the profile of the participants were not largely far from an average Singaporean.

Lastly, future studies can build on our findings by investigating alternative determinants of consumer demand to further underpin Singapore’s ongoing efforts to realize food self-sufficiency.