Knowledge Creation for Digital Innovation in Malaysia: Practitioners’ Standpoint

Abstract

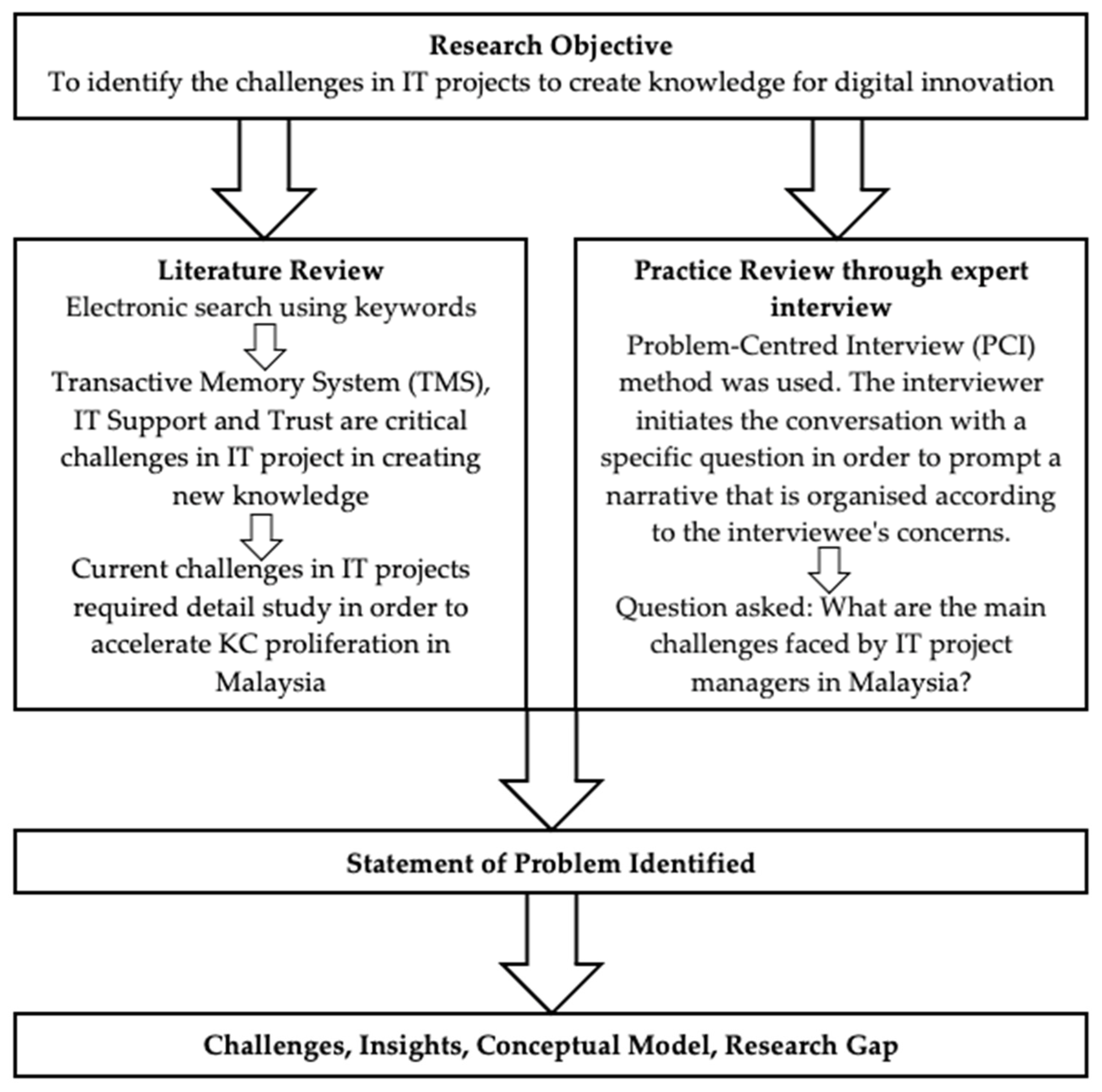

:1. Introduction

- What are the challenges faced by IT project managers?

- Based on a practitioners’ viewpoint, what are the possible factors that require attention in order to ensure knowledge creation leading to digital innovation?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Knowledge in Organisations

2.2. Knowledge Creation

2.3. Digital Innovation

2.4. Knowledge Creation in IT Projects and Digital Innovation (KC-IT-DI)

2.5. Current Challenges in IT Projects

- Transactive memory systems (TMS) is a cognitive system whereby individually specific information is encoded, stored and retrieved using a common cognitive structure focused on mutual understanding of each other’s specialized knowledge domains [49]. Although they may have had interactions with other team members through online conferencing, a personal bond may not have grown as a result of IT support.

- IT Support (ITS). ITS refers to the use of technology to aid in the maintenance of data storage, processing and transfer [50]. Lack of ITS, such as upfront analytics and data management, might put the project in jeopardy and create disasters in a variety of circumstances, such as offering misinformation in the meeting, opining or advising without solid supporting facts, or reacting emotionally to an occurrence [47,51].

- Team Learning (TL). TL refers to groups of people that work together to make positive behavioural changes [52]. TL promotes KC through debating, brainstorming, workshops, online forums and communities of practise [53]. Team members learn from one another through imitation, which leads to increased sensemaking and more sound decisions.

- Team Collaboration (TC). Remote project teams that lack team collaboration complicate matters for the project manager because team members are not based in an office and operate in different time zones, making it difficult to assemble for impromptu conversations for decision making [44]. For effective remote project teams, IT project managers must broaden their knowledge in order to facilitate project implementation while making the best use of their strengths [54]. Evidence from the studies revealed that project managers lack team learning in order to obtain the information required to manage projects, deal with obstacles during a crisis and establish competitive advantages [42,44,48].

- T-shaped skills (TSS). Project managers lack of TSS, which demonstrate the existence of in-depth knowledge and abilities in a certain area as well as an awareness of other fields required for the projects [46,55,56]. T-shaped skills refers individual who has in-depth knowledge and skills in a particular discipline and also has a background of other fields necessary to the projects [37]. It is vital to note that T-shaped skills allow for the expansion of team capabilities, allowing the team to be more agile, adaptive and robust throughout the project [57].

3. Methodology

4. Result

4.1. Practitioners’ Demographic Profile

4.2. Challenges in IT Projects (Research Question 1)

- Team related issues, particularly from remote team, knowledge gap and issues in communicating such knowledge between stakeholders. This refers to TMS, a method to leverage external memory to encode, store and retrieve knowledge.

| Challenges in IT Projects | Selected Excepts | Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Team related issues, particularly from remote team, knowledge gap and issues in communicating this knowledge between stakeholders. | Participant 1: “It is hard to identify the team knowledge.” Participant 4: “This may be a symptom of a lack of clear communication between the parties.” Participant 7: “The knowledge gap between technical or other teams with the project manager.” Participant 8: “One of the most frequent challenges connected with any project is the issue of communication and the inability to establish an efficient communication channel between parties.” | The inability to establish an efficient communication channel between parties. This may be a symptom of a lack of clear communication between the parties and a failure to identify the team’s knowledge gap. |

- b.

- Lack of sophisticated IT tools for project analysis. Table 7 shows the statement related to the lack of IT tools for project analysis. Project managers do not have analytic tools for daily tasks. Inadequate team collaboration highlights the team having difficulties to know true project situations and the follow ups are inaccurate.

| Challenges in IT Projects | Selected Except | Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of sophisticated IT tools for project analysis. | Participant 2: “The project manager is only being provided some necessary software, such as Microsoft Word, Excel and Project.” | The project managers lack of IT support. |

- c.

- Lack of in-depth knowledge and general skills in particular discipline involving estimating, risk and stakeholder management skills (Table 8).

| Challenges in IT Projects | Selected Excepts | Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of in-depth knowledge and general skills in particular discipline involving estimating, risk and stakeholder management skills. | Participant 3: “Things deteriorate further when the project experiences continual or uncontrolled scope development. This may be a symptom of a lack of stakeholder involvement.” Participant 4: “external factor, such as poor stakeholder management may result in the escalation of disputes.” Participant 6: A failure to manage stakeholders may result in a more serious issue.” Participant 8: “knowledge accumulation, experience review and organisational problems evaluation are all important.” Participant 10: “Project manager also lack of stakeholder management skills.” | Lack of stakeholder involvement in a project or scope development may be a cause for concern. Failure to manage stakeholders may result in a more serious issue. Knowledge accumulation, experience review and organisational problems evaluation are all important. |

5. Discussion

5.1. Antecedents of Knowledge Creation

5.2. Increase 3Cs in IT Project (Collaboration, Communciation and Coordination)

6. Limitations and Future Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. 2022. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=319&bul_id=UWpOUFBQSjk2TDhJNXFwUFhJZHNEUT09&menu_id=TE5CRUZCblh4ZTZMODZIbmk2aWRRQT09 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Pauleen, D.J.; Wang, W.Y. Does big data mean big knowledge? KM perspectives on big data and analytics. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiklhorn, D.; Wolny, M.; Austerjost, M.; Michalik, A. Digital lifecycle records as an instrument for inter-company knowledge management. Procedia CIRP 2020, 93, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Mendy, J. Evaluating people-related resilience and non-resilience barriers of SMEs’ internationalisation. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 27, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. The Knowledge-Creating Company. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 7, 162. Available online: https://hbr.org/2007/07/the-knowledge-creating-company (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Mehralian, G.; Nazari, J.A.; Ghasemzadeh, P. The effects of knowledge creation process on organizational performance using the BSC approach: The mediating role of intellectual capital. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, H.N. Plato in Twelve Volumes Trans; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, J.J.; Nonaka, I. The Application of Organizational Learning Theory to Japanese and American Management. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1986, 17, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R.; Konno, N. SECI, Ba and Leadership: A Unified Model of Dynamic Knowledge Creation. Long Range Plan. 2000, 33, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvinsson, L.; Malone, M. Realising Your Company’s True Value by Finding Its Hidden Brainpower; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R. Strategic management as distributed practical wisdom (phronesis). Ind. Corp. Chang. 2007, 16, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.-C.; Wu, C. The role of creation mode and social networking mode in knowledge creation performance: Mediation effect of creation process. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, N.; Schillaci, C.E. Intellectual capital in Society 5.0 by the lens of the knowledge creation theory. J. Intellect. Cap. 2021, 22, 478–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Nishihara, A.H. Introduction to the concepts and frameworks of knowledge-creating theory. In Knowledge Creation in Community Development; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, S.; Ahuja, M.; Kankanhalli, A. Does the source of external knowledge matter? Examining the role of customer co-creation and partner sourcing in knowledge creation and innovation. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelaya-Zamora, J.; Senoo, D. Synthesizing seeming incompatibilities to foster knowledge creation and innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Zhao, Q.; Hua, F. Impact of quality management practices on the knowledge creation process: The Chinese aviation firm perspective. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2013, 64, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berraies, S.; Chaher, M.; Yahia, K.B. Knowledge management enablers, knowledge creation process and innovation performance: An empirical study in Tunisian information and communication technologies sector. Bus. Manag. Strategy 2014, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N.I.; Masrek, M.N. Job design and knowledge productivity among administrative and diplomatic officers (PTD). J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 6, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.Q.; Le, H.M. The impact of knowledge management on innovation performance of small and medium enterprises—An empirical study in Lam Dong province. HCMCOUJS—Econ. Bus. Adm. 2018, 8, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, A.; Agrawal, R.K. Explicating the influence of shared goals and hope on knowledge sharing and knowledge creation in an emerging economic context. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 24, 172–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, M.L.L.; Choon-Yin, S.; Chai, Y.K.; Joo, J.H.A. Knowledge creation process, customer orientation and firm performance: Evidence from small hotels in Malaysia. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2020, 25, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.K.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.E.; Kim, C.J.; Song, J.H. Creativity and knowledge creation: The moderated mediating effect of perceived organizational support on psychological ownership. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 44, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, Y.M.; Tan, C.L.; Nasurdin, A.M.; Yeo, S.F.; Ramayah, T. Building a Knowledge-Intensive Medical Device Industry: The Effect of Knowledge Creation in R&D Project Performance. J. Pengur. 2020, 58, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, S.; Mohammadbeigi, A.; Gharlipour, Z.; Oskouei, A.O.; Gholami, S.S.; Rahbar, A. The Effect of Organizational Learning Culture Component on Knowledge Creation in Public Hospitals of Qom Province. Qom Univ. Med. Sci. J. 2021, 15, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.K.; Agrawal, R.K. It’s a knowledge centric world! Does ethical leadership promote knowledge sharing and knowledge creation? Psychological capital as mediator and shared goals as moderator. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JKM-09-2021-0669/full/html(accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Chatterjee, A.; Pereira, A.; Sarkar, B.; Chatterjee, A.; Pereira, A.; Sarkar, B. Learning transfer system inventory (LTSI) and knowledge creation in organizations. Learn. Organ. 2018, 25, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, A.; Santoro, G.; Tirabeni, L.; Monge, F. Social media as tool for facilitating knowledge creation and innovation in small and medium enterprises. Balt. J. Manag. 2018, 13, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimsdottir, E.; Edvardsson, I.R. Knowledge management, knowledge creation, and open innovation in Icelandic SMEs. Sage Open 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tootell, A.; Kyriazis, E.; Billsberry, J.; Ambrosini, V.; Garrett-Jones, S.; Wallace, G. Knowledge creation in complex inter-organizational arrangements: Understanding the barriers and enablers of university-industry knowledge creation in science-based cooperation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 25, 743–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Palladino, R.; Pezzi, A.; Kalisz, D.E. The role of digital innovation in knowledge management systems: A systematic literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, H.; Zhou, J. G-SECI model-based knowledge creation for CoPS innovation: The role of grey knowledge. Sage Open 2018, 22, 887–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ali, A.; Pitafi, A.H.; Khan, A.N.; Waqas, M. A socio-technical system approach to knowledge creation and team performance: Evidence from China. Inf. Technol. People 2020, 34, 1976–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanelt, A.; Firk, S.; Hildebrandt, B.; Kolbe, L.M. Digital M & A, digital innovation, and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisula, A.-M.; Blomqvist, K.; Bergman, J.-P.; Yrjölä, S. Organizing for knowledge creation in a strategic interorganizational innovation project. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2022, 40, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershina, R.; Soppe, B.; Thune, T.M. Bridging analog and digital expertise: Cross-domain collaboration and boundary-spanning tools in the creation of digital innovation. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.S.; Zainol, F.A. Knowledge Management Enablers, Process and Organizational Performance: Evidence from Malaysian Enterprises. Asian Soc. Sci. 2011, 7, 186. [Google Scholar]

- Nambisan, S. Digital Entrepreneurship: Toward a Digital Technology Perspective of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, M.L.; Rowe, F. Is IT changing the world? Conceptions of causality for information systems theorizing. Mis Q. 2018, 42, 1255–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, M.L.; Nan, W.V. Theorizing the connections between digital innovations and societal transformation: Learning from the case of M-Pesa in Kenya. In Handbook of Digital Innovation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; pp. 64–82.

- Landoni, M. Knowledge creation in state-owned enterprises. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2020, 53, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A.; Song, M. Digital Innovation Management: Reinventing Innovation Management Research in a Digital World. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y. Learning in Virtual Teams; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; De Smet, A.; Mysore, M.; Reimagining the Post Pandemic Workforce. McKinsey. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/reimagining-the-postpandemic-workforce (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Mian, A.; Khan, S. Coronavirus: The spread of misinformation. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, M.; Aravopoulou, E.; Evans, G.; AlDhaen, E.; Parnell, B.D. From information mismanagement to misinformation—The dark side of information management. Bottom Line 2019, 32, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnokutska, N.; Podoprykhina, T. Types and terminology of remote project teams. Eur. J. Manag. Issues 2020, 28, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D.M. Transactive memory: A contemporary analysis of the group mind. In Theories of Group Behavior; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bakopoulos, J.Y. Toward a More Precise Concept of Information Technology; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridg, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- International Data Corporation. IDC: The Premier Global Market Intelligence Company. Available online: https://www.idc.com/promo/global-ict-spending (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Argyris, C. Action science and organizational learning. J. Manag. Psychol. 1995, 10, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Baldwin, S.J. Using Technology to Support Student Learning in an Integrated STEM Learning Environment. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Sci. 2020, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betchoo, N.K. Managing Workplace Diversity: A Contemporary Context. Available online: http://lib.bvu.edu.vn/bitstream/TVDHBRVT/15790/1/Managing-Workplace-Diversity.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Madsen, S. The Power of Project Leadership: 7 Keys to Help You Transform from Project Manager to Project Leader; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hafeez-Baig, A.; Gururajan, R. Does Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Facilitate Knowledge Management Activities in the 21st Century? J. Softw. 2012, 7, 2437–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarco, T.; Lister, T. Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams, 3rd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, A.; Reiter, H. The Problem-Centred Interview; SAGE Publications: Singapore, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Choi, B. Knowledge Management Enablers, Processes, and Organizational Performance: An Integrative View and Empirical Examination. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 20, 179–228. [Google Scholar]

- Akgün, A.E.; Byrne, J.; Keskin, H.; Lynn, G.S.; Imamoglu, S.Z. Knowledge networks in new product development projects: A transactive memory perspective. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, D.G.; Lewis, K.; Kim, Y.; Patel, P.C.; Campion, M.C.; Thatcher, S.M.B. Transactive memory systems in context: A meta-analytic examination of contextual factors in transactive memory systems development and team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 464–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioduser, D.; Nachmias, R.; Forkosh-Baruch, A. New literacies for the knowledge society. In The International Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education: Part 2; Voogt, J., Knezek, G., Christensen, R., Lai, K.W., Pratt, K., Albion, P., Resta, P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, V.P.; Sreenivas, T. Critical Success Factors influencing the Knowledge Management of SME’s in Textile Industry. Int. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 4, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamoun, Y.; Wafa, S.A.; Hassan, R.A. The Impact of HR Strategy on Knowledge Capability in the Malaysian Electrical and Electronics Firms. J. Asian Acad. Appl. Bus. 2020, 6, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toni, A.F.; Pessot, E. Investigating organisational learning to master project complexity: An embedded case study. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 129, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, S.; Weiss, M.; Hoegl, M. Team learning from setbacks: A study in the context of start-up teams. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.P. Organizational Learning: The Contributing Processes and the Literatures. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Krogh, G. Care in Knowledge Creation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1998, 40, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobov, N. A Discursive Approach to Young Adult Romantic Couples Use of Active Listening to Manage Conflict During Natural Everyday Conversations. Int. J. List. 2022, 36, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, P.J.; Probst, T.M. Social values and social conflict in creative problem solving and categorization. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Year | Country | Key Factors to KC | Context | Research Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zelaya-Zamora and Senoo [17] | 2013 | Japan | Managerial influence | Research and development firm | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Shan et al. [18] | 2013 | China | Employee Training, Employee Involvement, Product Design, Benchmarking and Vision | Aviation firms | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Berraies et al. [19] | 2014 | Tunisia | Trust, Collaboration, Learning, Incentive and IT support | IT firms | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Yusof et al. [20] | 2016 | Malaysia | Work Scheduling Autonomy, Decision Making Autonomy, Work Methods Autonomy, Task Variety, Task Significance, Task Identity and Feedback from Job | Government federal ministry | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Pham and Le [21] | 2018 | Vietnam | Collaboration, Trust, Learning, Reward, Decentralization, Formalization, IT support and T-shaped skills | Small and medium enterprise | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Goswami and Agrawal [22] | 2018 | India | Share goal and Hope | IT firms | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Goyal et al. [16] | 2020 | United States and Singapore | Customer co-creation and Partner sourcing | Financial and IT firms | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Liow et al. [23] | 2020 | Malaysia | Customer orientation | Small Hotel | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Yoon et al. [24] | 2020 | South Korea | Creativity | Service Industry | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Yee et al. [25] | 2020 | Malaysia | Reward and Collaboration | Medical device firms | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Rahbar et al. [26] | 2021 | Iran | Learning Culture | Public Hospital | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Goswami and Agrawal [27] | 2022 | India | Ethical leadership and Psychological capital | IT firms, public sector research organisations, university and colleges | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Author | Year | Country | KC Research Gap | Context | Research Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mehralian et al. [6] | 2018 | Iran | Lack of studies have looked into how the intellectual capital and KC initiatives affects the success of businesses in the knowledge economy. | Pharmaceutical companies | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Chatterjee [28] | 2018 | India | SECI model has not undergone thorough empirical validation with construct impacting transfer of learning. | Organizations | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Papa et al. [29] | 2018 | Italy | Inadequate study of social media’s impact on KC and digital innovation. | Small and medium-sized enterprises | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Grimsdottir and Edvardsson [30] | 2018 | Iceland | Lack of studies on how KC may facilitate open-innovation ideas and practises. | Small and medium-sized enterprises | Qualitative, case study |

| Goyal et al. [16] | 2020 | United States and Singapore | Lack of studies connecting external knowledge and inputs from customers to internal innovation and KC. | Financial and IT firms | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Tootell et al. [31] | 2021 | Australia | There is currently a dearth of studies on the factors that promote KC at university-industry level | University-industry collaborations | Qualitative, semi-structured interview |

| Di Vaio et al. [32] | 2021 | Italy and France | There is a dearth of studies that examine how KC made possible by digital innovation to accelerate value creation. | n.a. | Bibliometric analysis |

| Li et al. [33] | 2018 | China | There is a dearth of studies that investigate the transfer of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge across teams between different organisations. | State-owned research institutes | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Cao et al. [34] | 2020 | China | Transactive Memory System’s effects on teams’ abilities to KC are overlooked. | Information Technology industry | Quantitative, survey questionnaire |

| Hanelt et al. [35] | 2021 | Germany | A handful of studies that focus on digital innovation, KC and its application. | Automotive manufacturers | Quantitative, Longitudinal study |

| Nisula et al. [36] | 2022 | Finland | Lack of studies have focused on the KC process in leading innovative projects. | Interorganizational innovation projects | Qualitative, semi-structured interview |

| Expert | Position | Credibility |

|---|---|---|

| Practitioner 1 | Project Manager | Project Management Professional (PMP®) |

| Practitioner 2 | Project Manager | Project Management Professional (PMP®) |

| Practitioner 3 | Project Manager | Projects IN Controlled Environments (PRINCE2®) |

| Practitioner 4 | Project Manager | Project Management Professional (PMP®) |

| Practitioner 5 | Project Manager | None |

| Practitioner 6 | Project Manager | Projects IN Controlled Environments (PRINCE2®) |

| Practitioner 7 | Project Manager | Project Management Professional (PMP®) |

| Practitioner 8 | Project Manager | None |

| Practitioner 9 | Project Manager | Project Management Professional (PMP®) |

| Practitioner 10 | Project Manager | Project Management Professional (PMP®) |

| Number of Working Experience in IT Project (Year) | Count (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| 5–9 | 5 (50%) |

| Above 10 | 5 (50%) |

| Project Management Certification | Count (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Project Management Professional (PMP®) | 6 (60%) |

| Projects IN Controlled Environments (PRINCE2®) | 2 (20%) |

| None | 2 (20%) |

| Selected Excepts | Axial Theme | Relevant Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Participant 1: “It is hard to identify the team knowledge. Therefore, how much work the remote team accomplishes and at what rate remains unclear. Moreover, the project has an unreasonable timetable for completing the task. Junior team members lack the necessary skills to work on a project and thus need additional supervision and assistance from more experienced team members. It is possible that unnecessary management intervention will result in the project not being completed on schedule.” | Team knowledge, Remote team, unreasonable timetable, lack of necessary skills, management intervention, delay in project completion | TMS, TSS |

| Participant 2: “The project manager is only being provided some necessary software, such as Microsoft Word, Excel and Project. IT support comes in as an essential tool for the PM to carry out project tasks. IT support helps in for PM to analyse data, understand requirements, compiling stats for business reporting, calculating efforts in anticipating project progress and financial, reviewing defects against business benefits for release considerations.” | Limited IT Support | ITS |

| Participant 3: “The remote team hard to know the true situation because it may not be told. The follow up will be not accurate. When several projects are operating in simultaneously, resource shortage is a constant problem. Furthermore, things deteriorate further when the project experiences continual or uncontrolled scope development. This may be a symptom of a lack of stakeholder involvement.” | Resource shortage, lack of stakeholder involvement, over-reaction to changes in funding | TMS, TC |

| Participant 4: “The working environment differences, such as network, workspace, etc., may cause a different understanding or result. This may be a symptom of a lack of clear communication between the parties. Alternatively, external factor, such as poor stakeholder management may result in the escalation of disputes.” | Variations in network and workplace, affect comprehension or outcome, poor communication, Poor stakeholder management, disagreements. | TC |

| Participant 5: “The customer gives unclear specifications. It is tough for the project team to meet their deadlines. Unrealistic timelines and resource limitations make it more difficult for the project team to fulfil the expectations of the clients. Other than scheduled meetings or discussions, sometimes, it’s challenging to connect with each other. The urgent issue will be complicated in this case as response time will be slower.” | Unpredictable deadlines, limited resources, inability to meet client expectations, slow response time | TC |

| Participant 6: “When the scope of a project is not adequately specified, recorded, or managed, it may result in the customer’s business needs altering. As a general matter, it is seen as detrimental. A failure to manage stakeholders may result in a more serious issue. Furthermore, the escalation is not clear for most of the cases when something happens.” | Unclear escalation | TC |

| Participant 7: “The knowledge gap between technical or other teams with the project manager. Therefore, the integration of communication and management skills into project management is critical to the success of the project. If the project’s objection is unclear and the team’s vision are not unified, it will be difficult to establish agreement on the project’s course of action.” | Poor communication and management skills | TSS, TC |

| Participant 8: “One of the most frequent challenges connected with any project is the issue of communication and the inability to establish an efficient communication channel between parties. The communication issues as there is still some cultural, language and distance barrier. In terms of project management, knowledge accumulation, experience review and organisational problems evaluation are all important.” | Communication | TC |

| Participant 9: “Keep the team motivated, bring diverse teams together so that they may succeed as a single unit and demonstrate leadership are all tough tasks to do. Other impacts, such as time zone, for example, the United States vs. Malaysia time differences are 12 h, fastest it will be one day in response time.” | Team engagement, leadership | TL |

| Participant 10: “Project managers lack knowledge in estimating the high-level effort and incoming risks that a PM needs to anticipate. This requires experience, time, as well as the right environment to acquire the skills. Project managers also lack stakeholder management skills. If a project manager knows how to manage people, projects can be well managed. People make or break a project, which is factual.” | knowledgeable project manager, | TSS, TL |

| Word Cloud | Themes | Mapping to Key Variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transactive Memory System | T-Shaped Skills | IT Support | ||

| team | people & technology | x | x | x |

| communication | people & technology | x | x | x |

| knowledge | people & technology | x | x | x |

| management | people | x | x | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tung, S.S.; Dorasamy, M.; Ab Razak, R. Knowledge Creation for Digital Innovation in Malaysia: Practitioners’ Standpoint. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912375

Tung SS, Dorasamy M, Ab Razak R. Knowledge Creation for Digital Innovation in Malaysia: Practitioners’ Standpoint. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912375

Chicago/Turabian StyleTung, Soon Seng, Magiswary Dorasamy, and Ruzanna Ab Razak. 2022. "Knowledge Creation for Digital Innovation in Malaysia: Practitioners’ Standpoint" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912375