Abstract

Communication through visual contents has become the new normal, and visual images and photographs are becoming the primary means of communication. People use Instagram not only for communication but also for identity seeking and self-expression. The casual sharing of digital photos on social networking sites has become a part of daily life, and there is a new phenomenon: people travel to take pictures to post on Instagram. In this circumstance, it is important to understand why people post photos on Instagram and who posts photos on Instagram. This study investigated the main and moderating effects of social–psychological motivations (i.e., social interaction, ideal-self presentation, true-self presentation) and an important personal trait, public self-consciousness, on the intention to post photos on Instagram. The study found that social–psychological motivations and public self-consciousness were positively associated with the intention to post photos on Instagram. This study also found a moderating role of public self-consciousness with social–psychological motivations on the intention to post photos on Instagram. Based on the study findings, the implications and directions for future research were discussed.

1. Introduction

The meanings and uses of digital contents have changed considerably after the emergence of the Internet and related technologies (e.g., Web 2.0, mobile technology, smartphones with camera performance). While product information has been traditionally produced, distributed, and controlled by suppliers, it is now easily created/recreated, distributed, and fortified by consumers. Social networking sites (SNSs) have become a major medium for people not only to interact with their friends but also to generate and disseminate information [1]. These days, people use SNSs as a major communication form in order to interact with others, create common interests, collaborate, share information, and express themselves to others [2].

Instagram is a photo and video sharing SNS founded in 2010. The name, Instagram, is a portmanteau of “instant camera” and “telegram”, so Instagram allows users to upload digital images that can be edited with filters and organized by hashtags and geographical tagging [3]. Instagram focuses on an image-oriented communication method, and it has attracted a response especially from Millennials and Generation Z, who are both more accustomed to multimedia rather than textual information [4]. In 2022, Instagram was the fourth-most-popular SNS in the world, in terms of user numbers, and it had over one billion monthly active users, accounting for 18.1% of all the people on Earth [4]. Instagram was the second-most-popular SNS in South Korea, and there were around 22.1 million Instagram users in South Korea in 2022, accounting for 42.5% of its entire population [5].

The proliferation of Instagram use has significantly changed consumer behaviors in travel and tourism contexts as well. Instagram has enabled users to create and share travel information (e.g., taking a photo of a hotel room and posting it on Instagram), and shared travel photos on Instagram significantly affect others’ decision-making about travel. While using Instagram, people incubate curiosity and fantasies about a place, through photos of travel destinations posted on Instagram by others; however, they, at the same time, create objects of curiosity and fantasy by sharing their own travel photos through Instagram [3]. Millennials and Generation Z search for travel information through Instagram, and they even search for local information (e.g., local cafes, local restaurants) on the site after arriving at a travel destination, rather than searching for such local information in advance.

In addition, Instagram has significantly changed travel-related behaviors and created a new phenomenon: people travel to take pictures to post on Instagram. There is a new word, “Instagrammable”, which means “worthy to post on Instagram” [6]. The Cambridge English Dictionary also included this word’s definition in its dictionary and defines it as “attractive or interesting enough to be suitable for photographing and posting on Instagram”. It is becoming increasingly important for tourism-related organizations and suppliers to create Instagrammable destinations, to attract more travelers. For example, some cafes that are popular on Instagram designate certain seats as “photo spots” and refrain from serving food to people in those seats, reserving them only for people taking photos [3]. Several museums and exhibition halls provide photo spots with colorful lighting and special sculptures for visitors to take pictures for Instagram, and some hotels also provide Instagrammable rooms for people to stay in [6]. Taking pictures of food in a restaurant and posting it on SNSs has become one of the world’s phenomena. Murphy [7] found that if a picture of food posted on SNSs received more “likes”, then people rated the food better.

Thus, Instagram is an important platform not only for promotion in marketing but also for communication with potential customers. Specifically, Instagram encourages its users to travel to take photos to post on Instagram. Accordingly, it is more important to understand why people post photos on Instagram in general, rather than focusing on the promotional roles of photos posted on Instagram in the travel and tourism contexts. The purpose of this study was to understand why people posted photos on Instagram and who posted photos on Instagram. Based on the literature reviewed, this study identified three factors of social–psychological motivation (i.e., social interaction, ideal-self presentation, true-self presentation) and an important personal trait, public self-consciousness, which affected the intention to post photos on Instagram. This study investigated the main and moderating effects of social–psychological motivations and public self-consciousness on the intention to post photos on Instagram.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Importance of Visual Communication

The human brain is made for visual processing, so people remember 80% of what they see but only 20% of what they do [8]. The human brain is hardwired for visual content, and, thus, visual information can be processed faster than text and is easier to remember [9]. For example, people can process about 36,000 visual messages per hour, while they can read about 15,000 words per hour on average [9]. People are taking in more data than ever before due to the Internet, social media, smartphones, and so on [10]. In the age of information overload, people are adapting to the deluge of information by utilizing visual information. According to Lurie and Mason [11], visual presentations (e.g., line graphs, bar charts) help people to process complex information comprised of a large number of texts and numbers in decision-making. Specifically, younger generations (e.g., Generation Z) do not read text the way previous generations have, so their skim reading and communicating through visual contents are becoming the new normal in the digital age [10].

Several well-known futurists [12,13,14,15] suggest that new technologies have transformed our society from an information society to an imagination society. There is no doubt to say that visual images, photographs, and videos are becoming the primary means of communication [16]. As technological development has made it easier for people to create and share visual contents, visual contents are taking over, from text contents, in most digital channels [17]. Infographics have become the standard visual contents for business and educational institutions to present concepts and data in a more appealing and engaging way [18]. Posts, tweets, articles, and ever-greater numbers of mobile messages are partially or wholly visual [17]. Visuals-driven SNSs, such as Instagram, Snapchat, and Pinterest, have succeeded in engaging users like no other social media platform [8].

After SNSs became the major platform for communication, the casual sharing of digital photos on SNSs have become a part of daily life, and people tend to present themselves visually on SNSs [19]. Jurgenson [19] argues that photos shared on SNSs differ from “true” photography because people are not meant to carry the same weight as a real “photographed” thing. Photography allows people to focus on what they wish to see and experience through framing, and it is easier for people to manipulate an image by creating an ideal version of their image by using the photo editing software [20]. People take photos to capture their current moment and for personal enjoyment, so they typically do not care if those photos represent the truth or not [19]. However, Belk [16] argues that there is also some evidence that photo sharing on SNSs is likely to accurately reveal personality characteristics. It seems that people use SNSs to engage in visual self-presentation of their actual and/or ideal selves [21].

The use of SNSs in daily life makes people perceive that there is no distinction between online and offline worlds, so people create and share their various selves by sharing digital photos and interacting with other users on SNSs. A person’s core self is no longer seen as singular because the self can be actively managed, jointly constructed and interactive on SNSs [16,22]. Haldrup and Larsen [23] suggest that social media and digital photography technology allow people to experiment with their identities [20,24]. While photos were traditionally used as a means of remembering, digital photos are now used not only for communication but also for identity seeking and self-presentation [25]. The digital photos posted on visuals-driven SNSs (e.g., Instagram) comprise the user’s extended selves and serve as cues for others to form impressions about the user [22]. By framing photos, people can exhibit their worldviews and a “romanticized self” to their SNS audiences, and, by doing so, they reconstruct and revitalize their everyday selves for idealization [20,26,27].

2.2. Social-Psychological Motivation

Several researchers have suggested that human beings’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the real or imagined presence of other people; therefore, the interplay between an individual and the social world should be examined [28,29]. Vogt and Fesenmaier [30] also suggested that social interaction and self-presentation should be examined as a single domain, the sign need. Sign is defined as the extension of self; however, the sign value can be achieved when an individual gains approval or recognition from others [29,30,31,32,33]. Accordingly, this study examined social interaction and self-presentation under the concept of social–psychological motivations.

Social interaction and self-presentation are important motives to use SNSs [34]. According to the self-presentation theory [35], people engage in projecting a desired image of themselves to others because they want to influence others and make others like them [34,36]. Instagram is an outlet mainly for self-presentation and impression management, through photo sharing. People use Instagram for self-presentation and promotion, rather than building and maintaining relationships; however, they still focus on validation or attention through the form of “likes” and “leave a comment”; therefore, social interaction should be examined in this study [21].

Humans are highly dependent on the social support of others [28,37]. The most obvious motive for people to use SNSs is to satisfy the need for integration and social interaction in order to gain social support [38]. The ultimate goal of social interaction is self-enhancement, which is often driven by one’s desire to gain approval (i.e., recognition and support from others) [29,39,40]. Instagram enhances the benefits of social interaction, such as gaining approval and recognition, because of Instagram’s features: “like”, “leave a comment”, and “share”. Instagram users feel good and self-enhanced when they receive a lot of likes, shares, and comments on their photos; accordingly, motivation for social interaction is positively related to the intention to post photos on Instagram.

Hypothesis 1.

Social interaction is positively associated with the intention to post photos on Instagram.

People have a desire to make their identities tangible, by associating themselves with tangible cues such as photos [41]. Self-presentation refers to using images and styles conveyed through one’s possession (e.g., physical goods, digital contents) to produce a desired self [42]. According to self-affirmation theory [43], people are motivated to affirm personal values in order to see themselves as competent and sensible individuals. As self-defining and self-expressive acts, people often purchase certain tangible goods that reflect who they are [44]. However, with the advent of technology, today’s younger people are more likely to use digital contents to present themselves, rather than physical goods [33]. The photos posted on Instagram tangibilize and reflect the users’ identity, as it demonstrates their accomplishments, skills, and/or tastes [45,46].

People possess and present multiple senses of their self [47]. There are mainly two aspects of self under a dual-goal approach: to make a good impression on others (i.e., ideal-self presentation) and to remain authentic (i.e., true-self presentation) [29,47,48,49,50]. The goal of ideal-self presentation is to create a public image of the self that is consistent with what a person would like to be [51]. People often engage in strategic action, such as presenting one’s ideal self to create and maintain a desired image of the self [33]. Ideal-self presentation aims to make a good impression on others; thus, ideal-self traits are generally positive [49].

True-self presentation is authentic and honest [52]. True-self traits include both positive and negative parts of a person [49]. True-self is defined as traits or characteristics that individuals possess and would like to possess, which they are not usually able to express in social settings [29,47,53]. However, Instagram is an open network, where users can build relationships based on similar interests and communicate freely with strangers. Instagram users can express their true-self better than in face-to-face contexts, and it satisfies their self-disclosure needs via feelings of anonymity and invisibility [22,47,54]. It is, therefore, assumed that people who are motivated to present themselves on Instagram for ideal-self and/or true-self reasons are more likely to post photos on Instagram.

Hypothesis 2.

Ideal-self presentation is positively associated with the intention to post photos on Instagram.

Hypothesis 3.

True-self presentation is positively associated with the intention to post photos on Instagram.

2.3. Public Self-Consciousness

Several researchers suggest that self-awareness, self-consciousness, and self-focused attention are very important for understanding human behaviors [55,56,57]. These researchers specifically suggest that self-consciousness plays an important role in determining an individual’s differences, attitudes, and behaviors. Self-consciousness is defined as the degree to which individuals habitually focus upon themselves [55]. As an individual’s persistent and consistent tendencies, self-consciousness is about how people see themselves and how people think others perceive them [55,57,58]. Fenigstein [59] suggests that self-consciousness includes two parts: private self-consciousness and public self-consciousness. Private self-consciousness refers to habitual attendance to our thoughts, motives, and feelings, while public self-consciousness refers to the awareness of oneself as a social object [55,57,58,60].

This study focuses on public self-consciousness, because it is important in understanding and predicting individuals’ SNS-use behaviors [61,62]. Researchers have found that people with a higher level of public self-consciousness are more likely to be concerned about how they appear to others, be concerned about making a positive impression on others, fear being judged by others, strongly desire to be with others and to monitor themselves, value relationships with others within the social and cultural groups, value social recognition and reputation, and respond more sensitively to the views of others [57,58,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. Due to these characteristics, such people tend to strategically engage in self-expression behaviors to gain social approval and recognition [60,61,62,67].

Instagram provides a means for users to express their identity by sharing their photos and videos. People who have a higher level of public self-consciousness show a tendency to form positive relationships with others and actively engage in activities to make friends. Therefore, they post/share photos very often on Instagram, and they are highly motivated to present and express themselves on Instagram [2,61,68,69]. Accordingly, public self-consciousness is positively related to the intention to post photos on Instagram.

A few researchers have found that public self-consciousness plays a moderating role in human behaviors. Shin, Anh, and Kang [58] found that public self-consciousness had significant interaction effects with basic psychological needs on social anxiety. Kim [70] also found that there was a significant interaction effect between public self-consciousness and identity achievement on social anxiety. Park and Woo [62] found that public self-consciousness moderated the advertising effect on attitude toward a travel destination. Yoo and Kim [71] found that public self-consciousness moderated the effect of airline service quality on perceived customer value. In addition, many studies have found differences in SNS-use behaviors (e.g., social interaction, self-expression, making friends, maintaining relationships) between the higher and lowers levels of public self-consciousness [61,68,69,72]. Accordingly, it is assumed that public self-consciousness moderates the effects of social–psychological motivation on the intention to post photos on Instagram.

Hypothesis 4.

Public self-consciousness is positively associated with the intention to post photos on Instagram.

Hypothesis 5.

There are interaction effects between social–psychological motivations (a. social interaction, b. ideal self-presentation, c. true-self presentation) and public self-consciousness on the intention to post photos on Instagram.

3. Methods

The study population of this study was Instagram users in South Korea. For this study, an online survey research method was utilized. By applying the nonprobability convenience sampling method, panel members of a panel company in South Korea were invited to participate in the study through an email with an online survey link. For the screening questions, the study participants were asked if they had an Instagram account, if they used Instagram at least once in the past 12 months, and if they had posted at least one photo in the past 12 months. Respondents who selected “yes” to all three questions were able to move on to the next question. The panel members who completed the survey received certain number of points, which could be converted into money.

The survey instrument consisted of five parts: motivation to post photos on Instagram (i.e., social interaction, ideal-self presentation, true-self presentation), intention to post photos on Instagram, public self-consciousness, Instagram-use behaviors, and demographic profiles. The measurement items were adopted from previous research, and most of them were modified in order to fit in the Instagram-use context. Motivation to post photos on Instagram consisted of three factors (i.e., social interaction, ideal-self presentation, true-self presentation) with 21 items. The measurement items were modified from Cho and Jun’s [29] study. Cho and Jun [29] translated Kim and Lee’s [49] English version into Korean, to apply in their study and verify its validity and reliability. Three items were used to measure social interaction, five items were used to measure ideal-self presentation, and four items were used to measure true-self presentation. Public self-consciousness was measured with four items from Kim’s [73] study. Kim [73] translated Scheier and Carver’s [74] English version into Korean and verified validity and reliability of the measurement items in their study. To measure intention to post photos on Instagram, respondents reported their agreement with three statements: “I will post photos on Instagram as part of my daily life”, “I will use Instagram to post photos”, and “I intend to keep using Instagram to post photos”. All items of the independent variables and the dependent variable were measured by using a 5-point Likert-type scale, in which “1” means strongly disagree and “5” means strongly agree. Furthermore, respondents were asked to provide information about their Instagram-use behaviors and demographic profiles (i.e., gender, age, level of education, annual household income).

4. Results

A panel company invited its 9,171 panel members to participate in this study, and 1,138 members attempted to participate in this study. The response rate was 12.41%. As discussed above, there were three screening questions (i.e., if they had an Instagram account, if they used Instagram at least once in the past 12 months, and if they had posted at least one photo in the past 12 months), and 622 members were qualified to continue to respond the survey questions. Out of the 622 members, 589 members completed the survey. Data from the respondents who answered all the survey questions related to our independent and dependent variables were utilized, and 562 were usable data for the statistical analyses.

The data collected were analyzed by using SPSS 22.0. About 58.5% of respondents were female (Table 1). One-third (30.6%) of respondents were between the ages of 10–19, one-third (30.6%) were between the ages of 20–29, and another one-third (31.9%) were between the ages of 30–39. Slightly less than half of respondents (46.4%) were university/college graduates, and 27.6% of respondents were middle/high school students. About two-fifth of respondents (42.3%) had an annual household income between USD 15,557 and USD 31,113. Related to their Instagram-use behaviors, the respondents spent an average of 90 minutes per day using Instagram, and they posted an average of 3.3 photos per week on Instagram.

Table 1.

Demographic profiles of respondents.

The results of factor analyses and reliability analyses are shown in Table 2. Factor analysis with the varimax rotation method was used to determine the primary structures [75]. Factor analysis was assessed to determine the meaningfulness of each dimension via the following principles: an eigenvalue over 1.00, variance explained by each component, and a factor loading score for each item that had a cut-off value of greater than 0.40 [75]. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.887, Bartlett’s tests were significant at p < 0.001, and the total variance extracted by the factors was 65.375%. The Cronbach’s alpha scores were 0.773 and higher. All results above indicated that the questionnaire used in this study reached relatively good construct validity.

Table 2.

Results of factor analysis and reliability analysis.

Before conducting the multiple regression analysis, the mean-centering method was applied because it made the results of the interaction effects a little more meaningful and, thus, easier to interpret. The independent variables were mean-centered to avoid the potential of multicollinearity in the interaction terms. As for the results, the VIF values were less than 2.00 (VIF Social Interaction (MSI) = 1.681, VIF Ideal-Self Presentation (MISP) = 1.810, VIF True-Self Presentation (MTSP) = 1.532, VIF Public Self-Consciousness (PSC) = 1.086, VIF MSIxPSC = 1.651, VIF MISPxPSC = 1.861, VIF MTSPxPSC = 1.394). All these results indicate that multicollinearity is not a potential problem in the data set.

Multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine the main effects and interaction effects of independent variables on the intention to post photos on Instagram (Table 3). The model was significant (F = 43.711 at p < 0.001), and R2adj was 0.348. Social interaction (β = 0.238, p < 0.001), ideal-self presentation (β = 0.142, p < 0.01), true-self presentation (β = 0.272, p < 0.001), and public self-consciousness (β = 0.174, p < 0.001) were significantly positively associated with the intention to post photos on Instagram. True-self presentation had the strongest effect, followed by social interaction, public self-consciousness and ideal-self presentation. There was a significant negative interaction effect of MTSP x PSC (β = −0.081, p < 0.05). The study results supported Hypotheses 1 through 4 and partially supported Hypothesis 5.

Table 3.

Results of multiple regression analysis on intention.

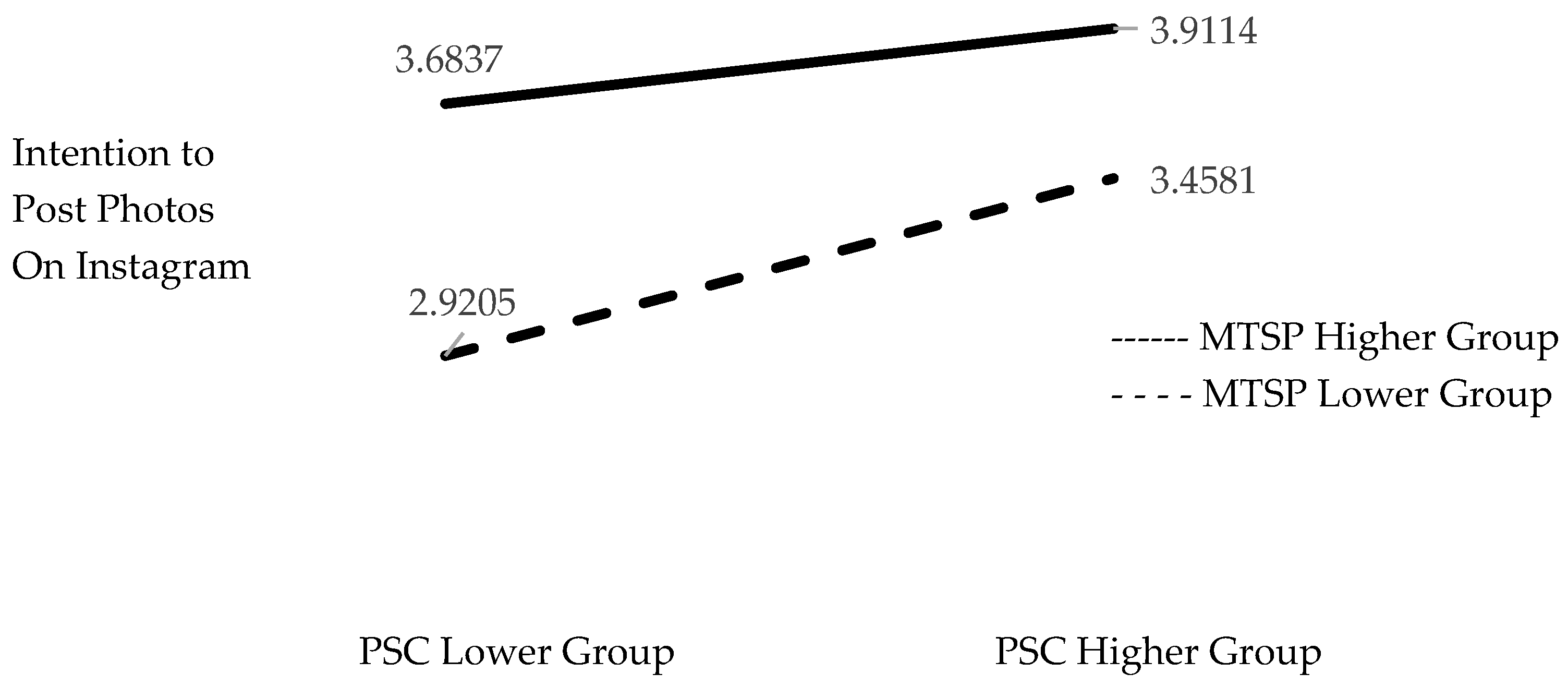

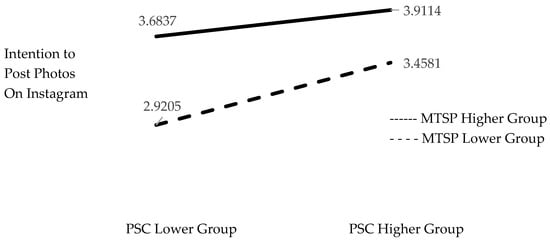

Due to the significant interaction effect found, further analyses were conducted. First, each data of two variables (i.e., true-self presentation, public self-consciousness) were separated into two groups (i.e., a lower group and a higher group), by using the median scores, and the mean scores of four groups (i.e., MTSP lower and higher groups and PSC lower and higher groups) were examined for comparison [76]. As illustrated in Figure 1, the intentional difference between the lower and higher groups of true-self presentation (M MTSP lower = 2.9205, M MTSP higher = 3.6837) for the lower public-self-consciousness group was greater than the intentional difference between the lower and higher groups of true-self presentation (M MTSP lower = 3.4581, M MTSP higher = 3.9114) for the higher public-self-consciousness group.

Figure 1.

Interaction effects of public self-consciousness and true-self presentation on intention.

Second, multiple regression analyses were conducted with each set of two groups of public self-consciousness (Table 3). In terms of the lower public-self-consciousness group, the model was significant (F = 49.505 at p < 0.001), and R2adj was 0.370. True-self presentation (β = 0.339, p < 0.001) and ideal-self presentation (β = 0.265, p < 0.001) were significantly positively associated with the intention to post photos on Instagram. In terms of the higher public-self-consciousness group, the model was significant (F = 34.862 at p < 0.001), and R2adj was 0.246. Social interaction (β = 0.343, p < 0.001) and true-self presentation (β = 0.214, p < 0.001) were significantly positively associated with the intention to post photos on Instagram.

5. Conclusions

Communicating through visual contents has become the new normal, and visual images and photographs are becoming the primary means of communication [10,16]. A visual-driven SNS, Instagram, has become a major platform for communication. In addition, people use Instagram not only for communication but also for identity seeking and self-expression. Casual sharing of digital photos on SNSs has become a part of daily life, and there is a new phenomenon: people travel to take pictures to post on Instagram. Many cafes, restaurants, and travel sites provide Instagrammable spots to attract potential customers [3,6]. Thus, it is important to understand why people post photos on Instagram and who posts photos on Instagram. This study investigated the effects of social–psychological motivations (i.e., social interaction, ideal-self presentation, true-self presentation) and an important personal trait, public self-consciousness, on the intention to post photos on Instagram. This study examined the main effects and interaction effects of social–psychological motivations and public self-consciousness on the intention to post photos on Instagram.

The results of this study support the finding of previous studies [28,29]: when investigating the motivation to use SNSs, an individual’s psychological and social understanding should be considered together. This study’s results also support Vogt and Fesenmaier’s [30] sign need, which includes symbolic expression (e.g., self-presentation) and social interaction (e.g., gaining approval). Instagram, a visuals-driven SNS, is a unique platform for self-expression, self-presentation, and impression management; therefore, social–psychological motivations should be examined to understand Instagram-use behaviors.

While the three factors (i.e., social interaction, idea-self presentation, true-self presentation) of social–psychological motivations were significantly positively associated with the intention to post photos on Instagram, this study revealed that true-self presentation had the strongest influence on the intention to post photos on Instagram. It is usually assumed that people use Instagram in order to maintain their reputation and people’s impression of them in a positive way; therefore, motivation for ideal-self presentation should have a stronger effect. However, this study’s results show the opposite. As discussed earlier, Instagram is unique in anonymity, compared to other SNSs such as Facebook. Therefore, people can be honest while using Instagram, and Instagram users can express their true-self, satisfying their self-disclosure needs and their feelings of anonymity and invisibility [22,47,54].

This study model was suggested based on the extended-self theory, and this study’s results support it, which assumes that people tend to present themselves by posting their digital photos on Instagram, and the digital photos represent their extended selves [22]. In addition, this study’s results support the self-presentation theory [35]: by sharing their photos on SNSs, people engage in projecting a desired image of themselves to others, as they want to influence others and make others like them [34,77,78].

Our study findings are consistent with the findings of previous research: people who have a higher level of public self-consciousness form positive relationships with others, and, thus, they are more likely to post/share photos on Instagram [2,61,62,68,69]. One of the primary findings of this study was that public self-consciousness played a significant moderating role, and this study was the first that introduced and investigated the moderating role of public self-consciousness with social–psychological motivations in the Instagram-use context. This study’s results indicate that for people at the lower level of the public self-consciousness condition, their motivation for true-self presentation has a significant effect on the intention to post photos on Instagram. However, for people at the higher level of the public self-consciousness condition, their motivation for true-self presentation has no significant effect on the intention to post photos on Instagram.

The results of the multiple regression analyses were also interesting: for the higher level of the public-self-consciousness group, the motivation for social interaction was a significant factor affecting the intention to post photos on Instagram. However, for the lower level of the public-self-consciousness group, the motivation for social interaction has no effect on the intention to post photos on Instagram. This can be explained by previous studies that suggest that people at the higher level of public self-consciousness are more likely to value social recognition and reputation [57,58,60,61,62], and social interaction is often driven by one’s desire for gaining approval (i.e., recognition and support from others) [29].

A contribution of this study is the identification of the significant roles of social–psychological motivations and public self-consciousness, in understanding who posts photos on Instagram and why. Social–psychological motivations and public self-consciousness, as suggested in this study, are important factors to predict photo-sharing behaviors on SNSs. These variables can be helpful in understanding why people use TikTok (a short-form video-sharing platform) and why they create Avatars in the Metaverse; therefore, this study’s model can be applicable in the contexts of different types of SNSs and the Metaverse.

Given the findings of the current study, practical implications are suggested. Instagram and other SNS companies need to provide features that satisfy social–psychological motivations, in order to encourage their users to post photos. This study suggests the importance of public self-consciousness in understanding and predicting individuals’ SNS-use behaviors. People at the higher level of public self-consciousness are more likely to use SNSs and post photos on SNSs, tend to express themselves on SNSs, and value social interaction through SNSs. Therefore, marketers should consider those people as the primary target market, to encourage those people to post photos related to their company’s products. However, people at the higher level of public self-consciousness are very sensitive to the reactions of others, care about how others evaluate them, have fear of being negatively evaluated by others, and eventually experience interpersonal anxiety [70]. Those experiences may affect depression. Recently, SNS companies have been criticized because SNS use may be linked to negative changes in their users’ mental health. SNS companies can develop socially responsible marketing campaigns, where they educate their users, especially those who are at the higher level of public self-consciousness. This study’s results also indicate that people at the lower level of public self-consciousness are motivated to post photos on Instagram for true-self presentation. It seems that those people use Instagram to search for self-meaning and seek their identity by sharing their photos. The SNS companies may provide new features that help users satisfy their innate desire for identity seeking and self-establishment; therefore, there should be further studies about providing new features for identity seeking and self-establishment. Finally, tourism-related organizations and suppliers should provide Instagrammable spots to attract more travelers. As discussed earlier, several cafes, museums, and hotels have provided Instagrammable photo spots, and they have succeeded in becoming well-known and attracting more customers [3,6,7]. These trends will continue due to the importance of visual communication [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,79].

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting this study’s findings. First, even though this study employed a fairly large sample of Instagram users, this study’s sample showed an over-representation of females, the 10–39 age group, and university/college graduates. Interpreting and generalizing this study’s results for other samples should be performed with caution. Second, the study participants were recruited from the panel members of a panel company, by using the nonprobability convenience sampling method. Therefore, generalization of the study results cannot be made about the whole study population. Third, the data were collected in South Korea. The study model should be tested with samples from other countries. Fourth, survey research depends on individuals’ retrospective judgment, and this may confound the direct causal effects; therefore, the study model may be re-examined with different research methods [80,81]. Finally, this study introduced and investigated the moderating role of public self-consciousness. However, this should be reinvestigated with various samples for replication. In addition, future research should also investigate whether there are other possible mediating or moderating variables, such as the self-esteem, self-confidence, anxiety, and covert narcissism of Instagram users.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of the data. Data are available from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Jun, S.H.; Hartwell, H.; Buhalis, D. Impacts of the Internet on travel satisfaction and overall life satisfaction. In Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life: Enhancing the Lives of Tourists and Residents of Host Communities; Uysal, M., Perdue, R., Sirgy, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 321–337. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Y.J.; Kim, H.H. The relationship public self-consciousness and SNS addiction of middle school students: The moderated mediation effect of fear of missing out and pubbing. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2021, 28, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.I. Virtual/actual tours in the COVID-19 pandemic: Cases of Instagram and non-landing tourism flights. J. Korean Assoc. Reg. Geogr. 2021, 27, 359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Number of Instagram Users Worldwide from 2020 to 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/183585/instagram-number-of-global-users/ (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- NapoleonCat. Instagram Users in Republic of Korea. Available online: https://napoleoncat.com/stats/instagram-users-in-republic_of_korea/2022/02/#:~:text=There%20were%2022%20132%20900,42.5%25%20of%20its%20entire%20population (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Ko, M.H. The impact of air passengers’ needs on intention to use Instagram on airplanes: Using ERG theory and the ETPB model. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 35, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K. First the Camera, Then the Fork. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/07/dining/07camera.html (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Entrepreneur Middle East Staff. Infographic: Five Scientific Reasons People Are Wired to Respond to Visual Marketing. Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/312551 (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- McCoy, E. How Our Brains Are Hardwired for Visual Content. Available online: https://killervisualstrategies.com/blog/how-our-brains-are-hardwired-for-visual-content.html (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Wolf, M. Skim Reading Is the New Normal. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/aug/25/skim-reading-new-normal-maryanne-wolf?utm_source=esp&utm_medium=Email&utm_cam%E2%80%A6 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Lurie, N.; Mason, C. Visual representation: Implications for decision making. J. Mark. 2007, 71, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R. The Dream Society: How the Coming Shift from Information to Imagination Will Transform Your Business; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.; Gilmore, J. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre and Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Postel, V. The Substance of Style: How the Rise of Aesthetic Value Is Remaking Commerce, Culture and Consciousness; Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R. Successful intelligence: Finding a balance. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 3, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Extended self and the digital world. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M. Research: Is a Picture Worth 1000 Words or 60,000 Words in Marketing? Available online: https://www.emailaudience.com/research-picture-worth-1000-words-marketing/ (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Boicheva, A. What is an Infographic: Theory, Tips, Examples and Mega Inspiration. Available online: https://graphicmama.com/blog/what-is-infographic/ (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Jurgenson, N. The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media; Verso Books: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, I.S.; McKercher, B. Ideal image in process: Online tourist photography and impression management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, T.M.; Maxwell-Smith, M.; Davis, J.; Giulietti, P. Lying or longing for likes? Narcissism, peer belonging, loneliness and normative versus deceptive like-seeking on Instagram in emerging adulthood. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Extended self in a digital world. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldrup, M.; Larsen, J. Tourism, Performance and the Everyday: Consuming the Orient; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianou-Lambert, T. Tourists with cameras: Reproducing or producing? Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1817–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijck, J. Digital photography: Communication, identity, memory. Vis. Commun. 2008, 7, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.; Yeh, J. Tourist photography: Signs of self. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. 2011, 5, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J. Display, identity and the everyday: Self-presentation through online image sharing. Discourse: Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2007, 28, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, E.; Wilson, T.; Akert, R. Social Psychology, 5th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.H.; Jun, S.H. Motivations for Facebook use and college student’s self-esteem and life satisfaction. J. Int. Trade Commer. 2016, 12, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, C.; Fesenmaier, D. Expanding the functional information search model. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 551–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Possessions and the extended self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimanche, F.; Samdahl, D. Leisure as symbolic consumption: A conceptualization and prospectus for future research. Leis. Sci. 1994, 16, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schau, H.; Gilly, M. We are what we post? Self-presentation in personal web space. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Chan, H.C.; Kankanhalli, A. What motivates people to purchase digital items on virtual community websites? The desire for online self-presentation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 1232–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Doubleday: Garden City, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Chan, A. Knowledge sharing and social media: Altruism, perceived online attachment motivation, and perceived online relationship commitment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 39, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mick, D. Consumer research and semiotics: Exploring the morphology of signs, symbols, and significance. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, S.; Park, N.; Kee, K. Is there social capital in a social network site?: Facebook use and college students’ life satisfaction, trust, and participation. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2009, 14, 875–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, D.; Mitra, K.; Webster, C. Word-of-mouth communications: A motivational analysis. Adv. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 527–531. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, S.H.; Noh, J.H. Impacts of SNS attachment and travel product satisfaction on motivations for sharing product experiences on SNSs. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2015, 27, 411–432. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.; Hirschman, E. Understanding the socialized body: A poststructuralist analysis of consumers’ self-conceptions, body images, and self-care products. J. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C. The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, C.; Sood, S. Self-affirmation through the choice of highly aesthetic products. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, G. Culture and Consumption: New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, S.E.; Kleine, R.E.; Kernan, J.B. These are a few of my favorite things: Toward an explication of attachment as a consumer behavior construct. Adv. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh, J.A.; McKenna, K.; Fitzsimons, G. Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the “true self” on the Internet. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human, L.; Biesanz, J.; Parisotto, K.; Dunn, E. Your best self helps reveal your true self: Positive self-presentation leads to more accurate personality impressions. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2012, 3, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J. The Facebook paths to happiness: Effects of the number of Facebook friends and self-presentation on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 6, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lee, J.; Kwon, S. Use of social-networking sites and subjective well-being: A study in South Korea. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Self-discrepancy theory. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 1120–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, R.; Hicks, J.; King, L.; Arndt, J. Feeling like you know who you are: Perceived true self-knowledge and meaning in life. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitty, M. revealing the “real” me, searching for the “actual” you: Presentations of self on an Internet dating site. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 24, 1707–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, L. Motives for Facebook use and expressing “True Self” on the Internet. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1510–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenigstein, A.; Scheier, M.F.; Buss, A.H. Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1975, 43, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystedt, L.; Ljungberg, A. Facets of private and public self-consciousness: Construct and discriminant validity. Eur. J. Personal. 2002, 16, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J. The influences of boredom proneness, public self-consciousness, and dressing style on internet shopping. Res. J. Costume Cult. 2015, 23, 876–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Anh, E.; Kang, B. Moderating effects of basic psychological need satisfaction on the relation between public self-consciousness and social anxiety in high school girls. Korean J. Sch. Psychol. 2016, 13, 497–519. [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein, A. Private and public self-consciousness. In Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior; Leary, M.R., Hoyle, R.H., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 495–511. [Google Scholar]

- Kwahk, C.H.; Hong, H.Y. The influence of public self-consciousness on SNS addiction of university students: The mediating effects of social anxiety and interpersonal problem. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2018, 25, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Kang, M. The effect of SNS use patterns on high school students’ self-esteem and public self-consciousness. Stud. Korean Youth 2013, 24, 33–65. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.; Woo, Y.H. Advertising effects depending on picture types of the sights and Facebook user’s public self-consciousness. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2019, 10, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman, B.J. What’s in a name? The moderating role of public self-consciousness on the relation between brand label and brand preference. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, B.G.; Dutton, D.L. Developmental antecedents of private self-consciousness, public self-consciousness and social anxiety. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 1990, 116, 275–297. [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker, B.R.; Leary, M.R. Social anxiety and self-presentation: A conceptualization and model. Psychol. Bull. 1982, 92, 641–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobey, E.; Tunnel, G. Predicting our impressions on others: Effects of public self-consciousness and acting, a self-monitoring subscale. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 7, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.H.; Yoo, T.S. Directional relationships of public self-consciousness and sociocultural attitudes toward appearance and objectified body consciousness on image management behaviors. J. Korean Soc. Cloth. Text. 2011, 35, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.J.; Moore, D.C.; Park, E.A.; Park, S.G. Who wants to be “friend-rich”? Social compensatory friending on Facebook and the moderating role of public self-consciousness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, M.; Lee, M.J.; Park, S.H. Photograph use on social network sites among South Korean college students: The role of public and private self-consciousness. Cyber Psychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.R. Mediating and moderating effect of identity achievement in the relation between public self-consciousness and social anxiety. Korean J. Couns. 2011, 12, 721–738. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.H.; Kim, M.S. The effect of airline service quality on the perceived customer value and attitude. J. Aviat. Manag. Soc. Korea 2018, 16, 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, P. The effect of college students’ adult attachment on social media addiction tendency: Mediating effect of public consciousness. J. Sch. Soc. Work. 2021, 53, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S. The role of functional congruity and self-congruity as a way to retain customer of mobile communication company: Focused on functional benefit and symbolic benefit from smartphone. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2013, 26, 1055–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S. The self-consciousness scale: A revised version for use with general populations. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 15, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.S. Structural Equation Model Analysis; Hanarae Publications: Seoul, Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.R. Self-Presentation: Impression Management and Interpersonal Behavior; Westview Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, M.; Agarwal, R. Through a glass darkly: Information technology design, identity verification, and knowledge contribution in online communities. Inf. Syst. Res. 2007, 18, 42–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmo, F.J.R.; Díaz, J.B. From tweet to photography, the evolution of political communication on Twitter to the image: The case of the debate on the State of the nation in Spain. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2016, 71, 108–123. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, S.H.; Vogt, C. Travel information processing applying a dual-process model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.; Cacioppo, J.; Schumann, D. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).