The Contribution of Local Agents and Citizens to Sustainable Development: The Portuguese Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

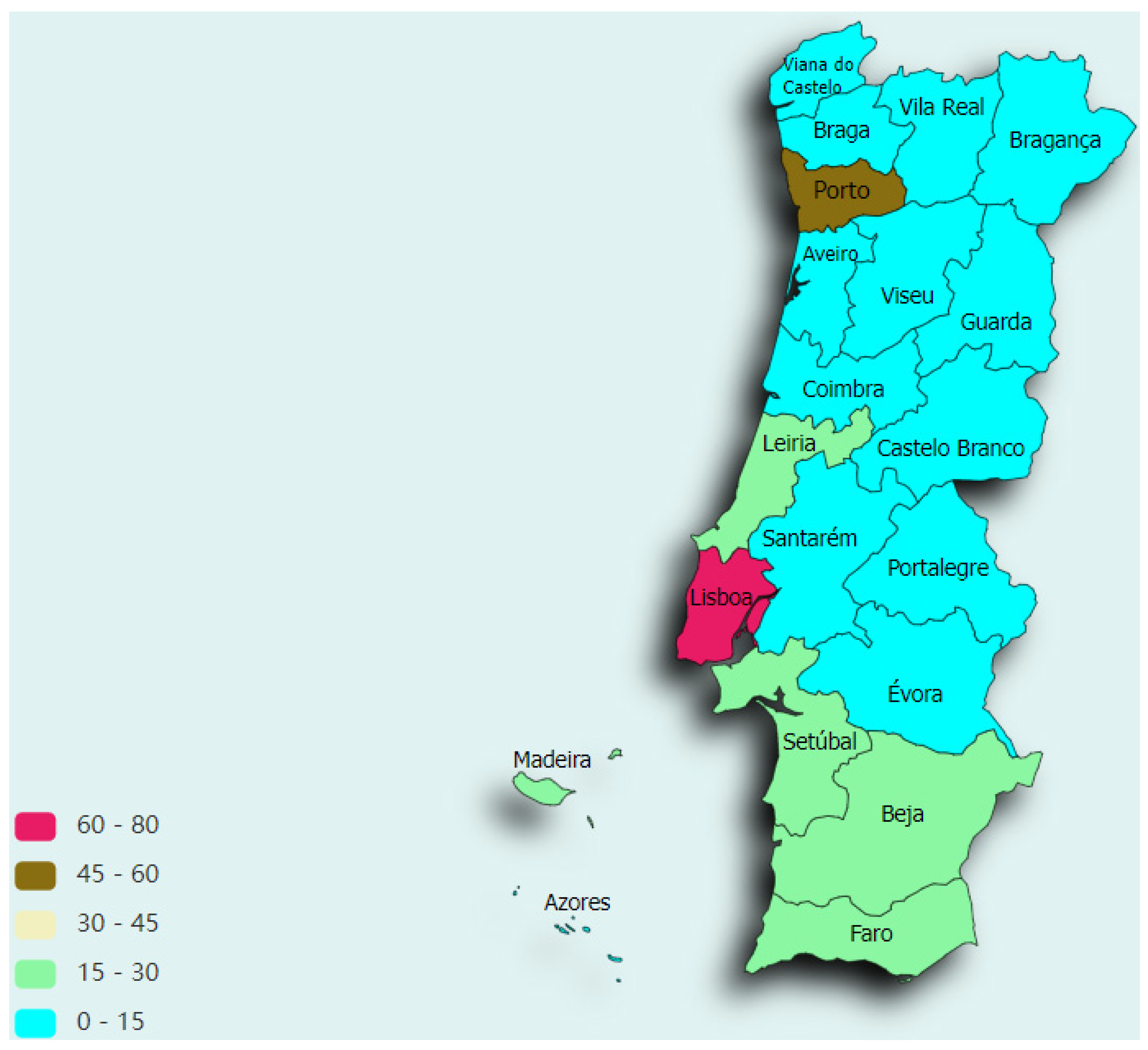

- RQ1. How can the geographical distribution of sustainability projects in Portugal promoted at the municipal level be characterized?

- RQ2. What is the relevance of population density and municipal GDP in characterizing the emergence of these projects?

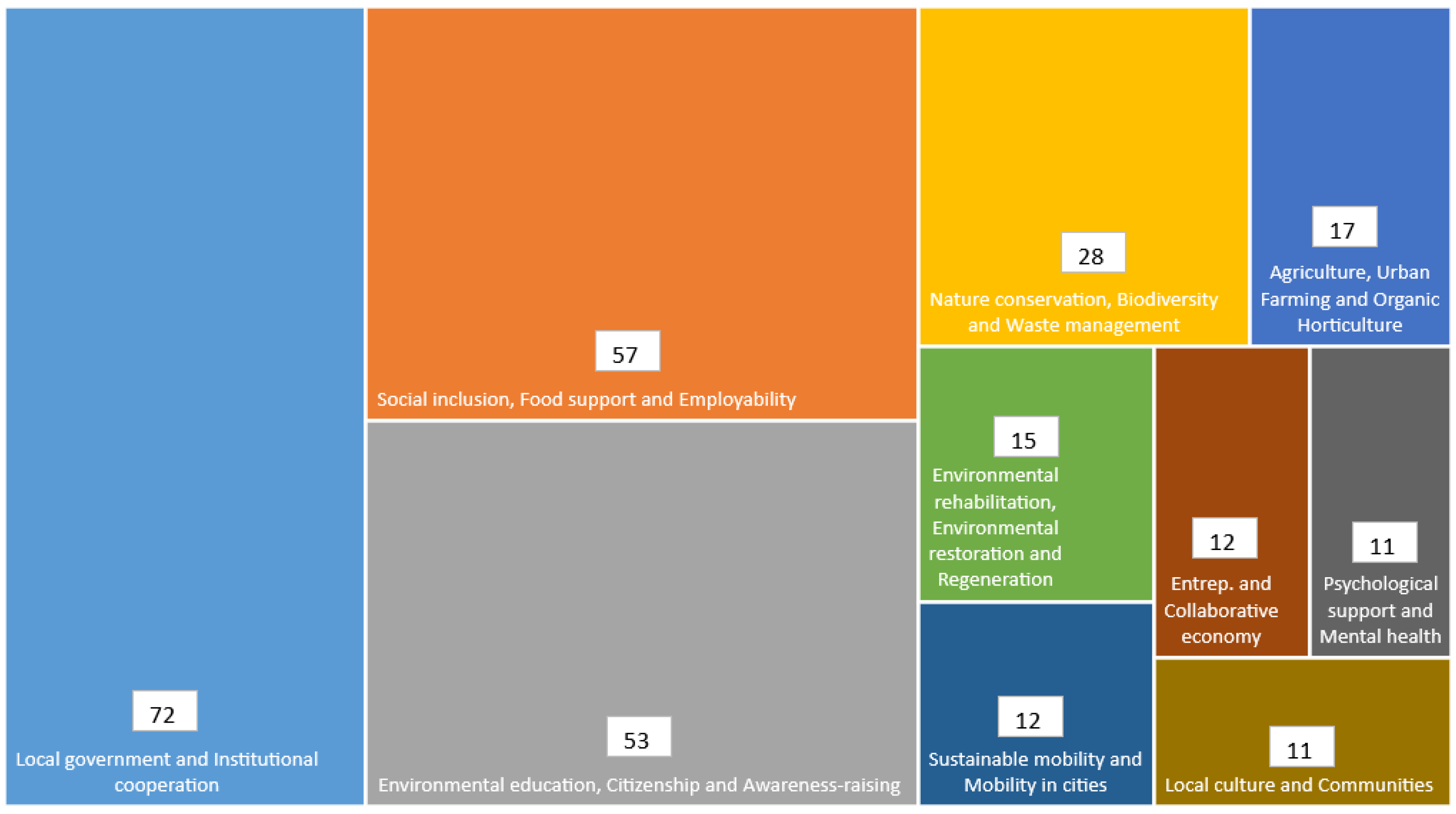

- RQ3. What are the sustainable development goals addressed by these projects?

- RQ4. What are the main themes addressed in these sustainable projects?

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

- PD—Intensity of population expressed by the ratio between the number of inhabitants of a given territorial area and the surface of that territory (usually expressed in number of inhabitants per square kilometer). The data refer to the year 2021;

- GDP—Indicator intends to translate the purchasing power manifested daily, in per capita terms, in the different municipalities. The data are relative to the year 2019.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Analysis

4.2. Qualitative Exploration

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations

6.3. Final Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Municipality | District | No. of Projects | PD (ind./km2) | GDP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Águeda | Aveiro | 1 | 137.6 | 86.59 |

| Aljezur | Faro | 3 | 18.7 | 67.13 |

| Almada | Setúbal | 3 | 2532 | 109.16 |

| Azambuja | Lisboa | 3 | 81.6 | 98.86 |

| Bragança | Bragança | 2 | 29.5 | 96.95 |

| Calheta | Azores | 2 | 27.2 | 77.68 |

| Cascais | Lisboa | 31 | 2198.7 | 117.95 |

| Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | 7 | 11.8 | 84.11 |

| Coruche | Santarém | 12 | 15.6 | 77.24 |

| Funchal | Madeira | 19 | 1388 | 115.71 |

| Fundão | Castelo Branco | 1 | 37.9 | 78.88 |

| Guimarães | Braga | 2 | 650.8 | 91.3 |

| Leiria | Leiria | 10 | 227.6 | 103.21 |

| Lisboa | Lisboa | 27 | 5456.5 | 205.62 |

| Loulé | Faro | 18 | 94.7 | 109.34 |

| Lousada | Porto | 3 | 493.1 | 72.58 |

| Madalena | Azores | 2 | 43 | 90.57 |

| Marco de Canaveses | Porto | 6 | 245.4 | 73.54 |

| Matosinhos | Porto | 7 | 2764.9 | 130.63 |

| Mértola | Beja | 19 | 4.8 | 68.69 |

| Odemira | Beja | 1 | 17.2 | 85.58 |

| Oeiras | Lisboa | 7 | 3743.8 | 153.13 |

| Pombal | Leiria | 13 | 81.7 | 82.72 |

| Porto | Porto | 8 | 5597 | 154.02 |

| Porto Santo | Madeira | 2 | 120.7 | 96.35 |

| São Roque do Pico | Azores | 2 | 22.6 | 79.4 |

| Seia | Guarda | 2 | 49.9 | 76.58 |

| Seixal | Setúbal | 11 | 1744.6 | 91.16 |

| Setúbal | Setúbal | 9 | 536.3 | 107.95 |

| Torres vedras | Lisboa | 9 | 204 | 96.37 |

| Viana do Castelo | Viana do Castelo | 2 | 268.9 | 93.77 |

| Vila Franca do Campo | Azores | 3 | 132.4 | 66.12 |

| Vila Nova de Gaia | Porto | 33 | 1803.7 | 100.55 |

| Vila Nova de Poiares | Coimbra | 1 | 80.6 | 71.42 |

References

- Heaviside, C. Understanding the Impacts of Climate Change on Health to Better Manage Adaptation Action. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maibach, E.W.; Nisbet, M.; Baldwin, P.; Akerlof, K.; Diao, G. Reframing climate change as a public health issue: An exploratory study of public reactions. BMC Pub. Health 2010, 10, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z. Impact of Climate Change on the Global Environment and Associated Human Health. Open Access Lib. J. 2018, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Purohit, B.M. Public Health Impacts of Global Warming and Climate Change. Peace Rev. 2014, 26, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunningham, N. Enforcing Environmental Regulation. J. Environ. Law 2011, 23, 169–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodeiro, C.; Capelo-Martínez, J.L.; Santos, H.M.; Oliveira, E. Impacts of environmental issues on health and well-being: A global pollution challenge. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 2021, 28, 18309–18313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajat, A.; Hsia, C.; O’Neill, M.S. Socioeconomic Disparities and Air Pollution Exposure: A Global Review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpentier, C.L.; Braun, H. Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development: A powerful global framework. J. Int. Counc. Small Bus. 2020, 1, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, G. The 2030 Agenda and eradicating poverty: New horizons for global social policy? Glob. Soc. Pol. 2017, 17, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, O.; Stoett, P. Citizen Participation in the UN Sustainable Development Goals Consultation Process: Toward Global Democratic Governance? Glob. Govern. 2016, 22, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, D.; Fortier, F.; Boucher, J.F.; Riffon, O.; Villeneuve, C. Sustainable development goal interactions: An analysis based on the five pillars of the 2030 agenda. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Kawakubo, S.; Okitasari, M.; Morita, K. Exploring the role of local governments as intermediaries to facilitate partnerships for the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Cit. Soc. 2022, 82, 103883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, R. Democratic Practice. In Origins of the Iberian Divide in Political Inclusion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, B.M. Regionalização, a Eterna Reforma Adiada. Available online: https://observador.pt/opiniao/regionalizacao-a-eterna-reforma-adiada/ (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Rodrigues, C. Participation and the Quality of Democracy in Portugal. Rev. Crit. Cienc. Soc. 2015, 108, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauginiené, L.; Butkeviciené, E.; Vohland, K.; Heinisch, B.; Daskolia, M.; Suskevics, M.; Portela, M.; Balázs, B.; Pruse, B. Citizen science in the social sciences and humanities: The power of interdisciplinarity. Palgrave Comm. 2020, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.K. Crowdsourcing: Citizens as coproducers of public services. Pol. Int. 2021, 13, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S.; Barnes, A.; Lee, C.; Mead, R.; Clowes, M. Increasing public participation and influence in local decision-making to address social determinants of health: A systematic review examining initiatives and theories. Loc. Govern. Stud. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadaki, M.; Sinner, J.; Chan, K.M.A. Making sense of environmental values: A typology of concepts. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, R. Sustainability, responsibility and ethics: Different concepts for a single path. Soc. Resp. J. 2021, 17, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, S.; Ojanen, M.; Ott, A.; Saarikovski, H. What about citizens? A literature review of citizen engagement in sustainability transitions research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A. Modern Interpretations of Sustainable Development. J. Law Soc. 2009, 36, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan-Aggrey, E.; Arku, G.; Atuoye, K.; Kyeremeh, E. Mobilizing ‘communities of practice’ for local development and accleration of the Sustainable Development Goals. Loc. Econ. J. Loc. Econ. Pol. Unit 2022, 37, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W. Consumer behaviour and environmental sustainability. J. Cons. Behav. 2020, 19, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, K.; Su, J. Investigating consumer behaviour for environmental, sustainable and social apparel. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Tech. 2020, 33, 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunden, C.; Atis, E.; Salali, H.E. Investigating consumers’ green values and food-related behaviours in Turkey. Int. J. Cons. Stud. 2020, 44, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosta, M.; Zabkar, V. Antecedents of Environmentally and Socially Responsible Sustainable Consumer Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Saengon, P.; Alganad, A.M.; Chongcharoen, D.; Farrukh, M. Consumer green behaviour: An approach towards environmental sustainability. Sustain. Develop. 2020, 28, 1168–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Z.; Coffman, D.M. The sharing economy promotes sustainable societies. Nat. Comm. 2019, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. Growth Theory through the Lens of Development Economics. Hand. Econ. Grow. 2005, 1, 473–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muringani, J.; Fitjar, R.D.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Social capital and economic growth in the regions of Europe. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2021, 53, 1412–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquet, R.; Broadberry, S. Seven centuries of European economic growth and decline. J. Econ. Perspect. 2015, 29, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekrep, A.; Strasek, S.; Borsic, D. Productivity and Economic Growth in the European Union: Impact of Investment in Research and Development. Our Econ. 2018, 64, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.; Sharma, S.; Halme, M. Poverty, Business Strategy, and Sustainable Development. Org. Environ. 2016, 29, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senadheera, S.; Withana, P.A.; Dissanayake, P.D.; Sarkar, B.; Chopra, S.; Rhee, J.H.; Ok, Y.S. Scoring environment pillar in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) assessment. Sustain. Environ. 2021, 7, 1960097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, D.; Gibson, M.A.; Lawson, D.W.; Sear, R. Human behavioral ecology: Current research and future prospects. Behav. Ecol. 2013, 24, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Warner, M.E.; Homsy, G.C. Environment, Equity, and Economic Development Goals: Understanding Differences in Local Economic Development Strategies. Econ. Dev. Quart. 2017, 31, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.D. Sustainable Development and Social Justice: Conflicting Urgencies and the Search for Common Ground in Urban and Regional Planning. Michigan J. Sustain. 2013, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.J.; Strange, R. The governance of the global factory: Location and control of world economic activity. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 29, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Hickmann, T.; Sénit, C.A.; Beisheim, M.; Bernstein, S.; Chasek, P.; Grob, L.; Kim, R.E.; Kotzé, L.; Nilsson, M.; et al. Scientific evidence on the political impact of the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boto-Álvarez, A.; Garcia-Fernández, R. Implementation of the 2030 Agenda Sustainable Development Goals in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Okitasari, M.; Morita, K.; Katramiz, T.; Shimizu, H.; Kawakubo, S.; Kataoka, Y. SDGs mainstreaming at the local level: Case studies from Japan. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1539–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhof, P.D. Localizing the Sustainable Development Goals to Accelerate Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Govern. Brief 2018, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnault, A.; Willgoss, T.; Barbic, S. Towards the use of mixed methods inquiry as best practice in health outcomes research. J. Pat. Rep. Outc. 2018, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, R.L.; Longnecker, M.T. An Introduction to Statistical Methods and Data Analysis; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Potluka, O.; Sancino, A.; Diamond, J.; Rees, J. Place leadership and the role of the third sector and civil society. Volunt. Sect. Rev. 2021, 12, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.R. Measuring Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals: Creativity, Intellectual Capital, and Innovation. In Handbook of Research on Novel Practices and Current Successes in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals; Popescu, C., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, M. Learning from Local Government Research Partnerships in a Fragmented Political Setting. Pub. Admin. Rev. 2021, 81, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, G.; Lindhult, E. A systems perspective on systemic innovation. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 38, 635–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measuring Business Impacts on People’s Well-Being and Sustainability. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/fr/investissement/measuring-business-impacts-on-peoples-well-being.htm (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Dichev, C.; Dicheva, D. Gamifying education: What is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain: A critical review. Int. J. Educ. Tech. High. Educ. 2017, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofosu-Ampong, K. The Shift to Gamification in Education: A Review on Dominant Issues. J. Educ. Tech. Syst. 2020, 49, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaborn, K.; Fels, D. Gamification in Theory and Action: A Survey. Int. J. Hum. Comp. Stud. 2015, 74, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M.; Homner, L. The Gamification of Learning: A Meta-analysis. Educ. Psych. Rev. 2020, 32, 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.P.; Souza, C.G.; Reis, A.C.; Souza, W.M. Gamification in E-Learning and Sustainability: A Theoretical Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessell, S. Rethinking Child Poverty. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2021; In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, E.P.; Hinnig, M.P.; Costa, E.M.; Marques, J.S.; Bastos, R.C.; Yigitcanlar, T. Sustainable development of smart cities: A systematic review of the literature. J. Open Innov. Tec. Mark. Compl. 2017, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Karvonen, A.; Luque-Ayala, A.; Martin, C.; McCormick, K.; Raven, R.; Palgan, Y.V. Smart and sustainable cities? Pipedreams, practicalities and possibilities. Loc. Environ. 2019, 24, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiri, M.; Azim, A.Z.; Farrokhi, M. Smart City Solution for Sustainable Urban Development. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F. The role of tech startups in the fight against COVID-19. World J. Sci. Tech. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 18, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; Zenchenko, S.; Tarasova, A.; Radyukova, Y. Management of Smart and Sustainable Cities in the Post-COVID-19 Era: Lessons and Implications. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.M. Portugal é o Segundo País da UE Onde as Pequenas Empresas Têm Maior Peso. Available online: https://eco.sapo.pt/2019/11/25/portugal-e-o-segundo-pais-da-ue-onde-as-pequenas-empresas-tem-maior-peso/ (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Kazimieras Zavadskas, E.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Chau, K.W. Sustainable Business Models: A Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolis, I.; Morioka, S.N.; Leite, W.K.d.S.; Zambroni-de-Souza, P.C. Sustainability Is All about Values: The Challenges of Considering Moral and Benefit Values in Business Model Decisions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor-Mach, D. What role for culture in the age of sustainable development? UNESCO’s advocacy in the 2030 Agenda negotiations. Int. J. Cult. Pol. 2020, 26, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsalis, T.A.; Kapsalis, V.C. Sustainable Development and Its Dependence on Local Community Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szetey, K.; Moallemi, E.A.; Ashton, E.; Butcher, M.; Sprunt, B.; Bryan, B.A. Co-creating local socioeconomic pathways for achieving the sustainable development goals. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1251–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusakabe, E. Advancing sustainable development at the local level: The case of machizukuri in Japanese cities. Prog. Plan. 2013, 80, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Sustainable Ecotourism Established on Local Communities and Its Assessment System in Costa Rica. J. Environ. Protect. 2013, 4, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M. Collaborative Networks Contribution to Sustainable Development. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2009, 41, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payumo, J.; He, G.; Manjunatha, A.C.; Higgins, D.; Calvert, S. Mapping Collaborations and Partnerships in SDG Research. Front. Res. Met. Anal. 2020, 5, 612442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitorino, A.P. Portugal and the Ocean Economy. UN Chron. 2017, 54, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, N. Portugal as an Old Sea Power. J. Territ. Marit. Stud. 2021, 8, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Min | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Mode | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 4.5 | 10.75 | 2 | 8.265 | 8.750 |

| Variable | Parametric | Nonparametric | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Kendall | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Spearm. | Sig. (2-Tailed) | |

| PD | 0.416 | 0.014 | 0.276 | 0.027 | 0.383 | 0.025 |

| GDP | 0.447 | 0.008 | 0.299 | 0.017 | 0.420 | 0.013 |

| Theme | Quote |

|---|---|

| Local government Institutional cooperation | “The Eco Card Schools is an innovative pilot project which aims to encourage the school community to improve good environmental practices in the field of solid waste management and selective waste disposal.” (Eco Card Schools Project) “The goal of the Cascais in Transition group is to create a local network to connect all those in the Cascais Municipality who wish, by sharing knowledge and affection, to move towards a more sustainable and happy life, celebrating what unites us while respecting what separates us.” (Cascais in Transition) “Zora is an associative movement of young people from Marco de Canaveses whose main objective is the development of the municipality of Marco de Canaveses.” (Zora—Marco de Canaveses) |

| Social inclusion Food support Employability | “The ZERO WASTE initiative was born from a citizenship movement, when in the middle of the economic and social crisis, huge amounts of meals and end-of-life food were being deposited in waste containers, usually in undifferentiated waste containers, which could have been recovered, for human food or, if not possible for human food, for animal feed or composting.” (Zero Waste) “The Cozinha com Alma is a social take-away open to the public that supports families in financial difficulty.” (Cozinha com Alma) “The Lighthouse House is a shelter for women in situations of social vulnerability, with or without children.” (Casa do Farol) |

| Environmental education Citizenship Awareness-raising | “The activity has a set of workshops related to environmental issues and promotion of well-being and covers pre-school students (public and solidarity network), the 1st CEB and special education in the municipality of Azambuja.” (A day in the Field) “This group intended to work on themes such as, the family’s responsibility in their children’s school path and the importance of the family relationship for the educational success of the students.” (Magic Ark) “The Salgueiro Maia Citizenship House opened to the public on 1 July and aims to promote the values of April, giving due recognition to a major figure of the revolution of 25 April 1974, Salgueiro Maia.” (Casa da Cidadania Salgueiro Maia) |

| Nature conservation Biodiversity Waste management | “Transforming plastic into useful everyday objects with the Precious Plastic machines.” (Reciclaro) “The Stork, Horse and Owl treks promote full contact with nature, people and animals, sharing with visitors all its heritage in terms of landscape and cork oak forest.” (PDC—Coruche) “The initiative aims to stimulate activities to enhance the material and immaterial value of endogenous resources, linked to natural, gastronomic and cultural tourism.” (Lince Territories) |

| Agriculture Urban Farming Organic Horticulture | “The Olivais Pedagogical Farm arose from the growing demand for contact with nature and the need to keep alive an increasingly distant and unknown reality, life in the countryside.” (Quinta Pedagógica dos Olivais) “It intends to respond to the threat to genetic heritage—the loss of biodiversity resulting from climate change, but also from the privatization of seeds and reduced viability of reproduction—by offering simple and effective alternatives for the preservation of genetic diversity.” (Germinate a seed bank) “Agroforestry is a natural space where forest, fruit and vegetable trees are planted or sown, aiming at maximum use of space and productivity, with the objective of forest recuperation, with the reintroduction and maintenance of native species.” (Bela Flor Respira) |

| Environmental rehabilitation Environmental restoration Regeneration | “The project consists of the environmental requalification of the pre-existing riverside path and to promote the organization of the various recreational and leisure activities that already occur along the left bank in the strip between the agricultural fields and the river.” (Sorraia River) “An Integrated Bio-, Phyto-Remediation and Aeration System will be installed in the Vala das Baleias (tributary of the Sorraia River) in order to reduce the state of eutrophication of this aquatic system, and nearby areas.” (Vala das Baleias) “A treatment solution for the wastewater produced by the population of the Curral dos Romeiros site promoting the safety and public health of the residential population at the Curral dos Romeiros site and avoiding the presence of unpleasant odors.” (Curral tos Romeiros) |

| Sustainable mobility Mobility in cities | “The project consists in the promotion and creation of an action cluster, promoting the safe and responsible use of the bicycle and its dynamization, demystification and economic valuation.” (Pedalada) “Lisboa Viva is a card that identifies the student and the school or school group to which he or she belongs and allows access to the public transport network in the 18 districts of the Lisbon Metropolitan Area.” (School Navegante Card) “The public shared bicycle system in the city of Loulé that is currently under public contracting foresees the implementation in the urban area of the city of 10 stations, 120 parking docks and 60 bicycles with electric support.” (Loulé Electric Bicycle Network) |

| Entrepreneurship Collaborative economy | “This project aims to transform an old cork factory, located about one kilometer from the center of the village of Ameixial, into a space for incubation and hosting of economic activities.” (Incubadora Ameixial) “The Balcão do Investidor (Investor Desk) was created to help boost the local economy by promoting investment and job creation.” (Balcão do Investidor) “The Viveiro de Lojas is an innovative initiative that intends to help densify the local commercial fabric with new and differentiated concepts.” (Viveiro de Lojas) |

| Psychological support Mental health | “Crescer a Brincar implemented in a classroom context, included in the school curriculum and is intended to promote the development of social and emotional skills, psychological adjustment and academic performance, preventing or reducing emotional and behavioral problems in 1st cycle children.” (Crescer a Brincar) “An innovative therapeutic program is proposed, integrated and conveyed through the practice of surfing, which aims to combat and prevent the pejorative symptoms that are evident in 348 children exposed to situations of risk in the Municipality of Matosinhos.” (Onda Social) “The Therapeutic Gardens project, presents itself as a pilot project to mitigate the lack of sociability, social isolation and passivity of the senior population, aggravated by the measures of confinement and social distancing imposed by the COVID pandemic.” (Therapeutic Gardens) |

| Local culture Communities | “The Project seeks to cover, in a transversal way, the contact with the cultural—traditional and geographical reality of the Municipality and consequently with its citizens.” (The journeys of Zambujinho) “In 2011 Azimute “rescued” an isolated, depopulated, and aging village, Portela, and turned it into an “Educational Village”, taking advantage of the existing infrastructures in the village and valuing the knowledge and life experience of its elderly inhabitants, giving them the designation of Masters.” (Aldeia Pedagógica de Portela) “Moinho do Papel is a water mill, rehabilitated by the Architect Álvaro Siza Vieira and considered an ex-libris of the industry’s history.” (Moinho do Papel) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almeida, F. The Contribution of Local Agents and Citizens to Sustainable Development: The Portuguese Experience. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912696

Almeida F. The Contribution of Local Agents and Citizens to Sustainable Development: The Portuguese Experience. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912696

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmeida, Fernando. 2022. "The Contribution of Local Agents and Citizens to Sustainable Development: The Portuguese Experience" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912696

APA StyleAlmeida, F. (2022). The Contribution of Local Agents and Citizens to Sustainable Development: The Portuguese Experience. Sustainability, 14(19), 12696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912696