CSR Commitment, Alignment and Firm Performance: The Case of the Australia-China Tourism Supply Chain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

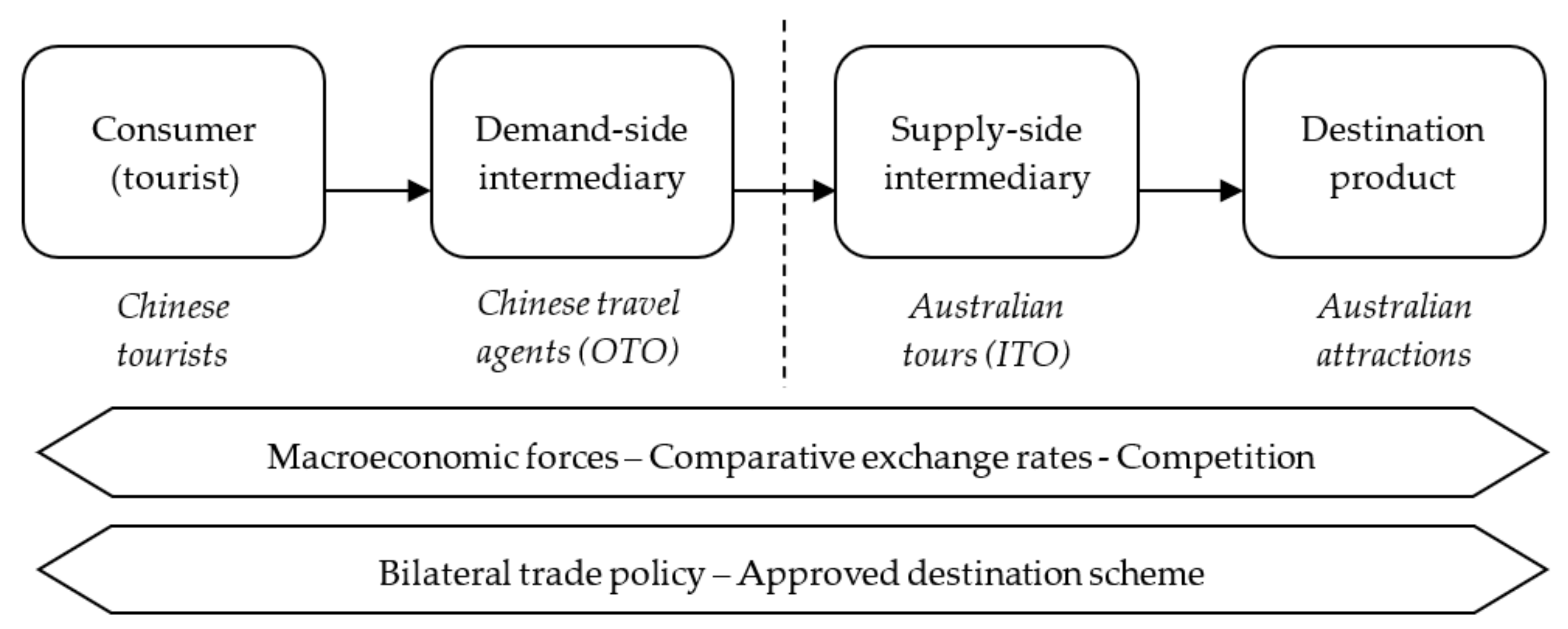

1.1. Australia–China Tourism Supply Chain

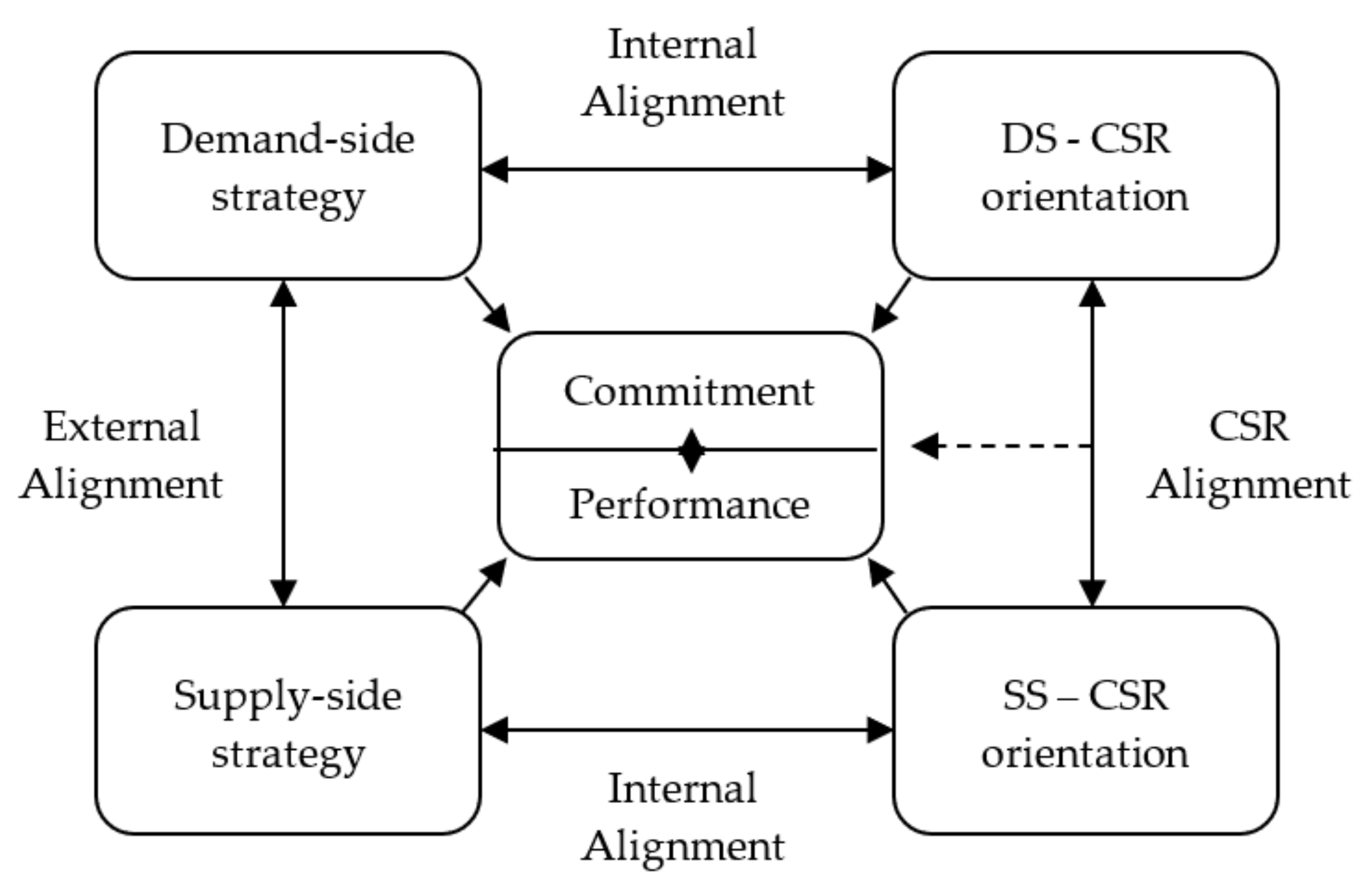

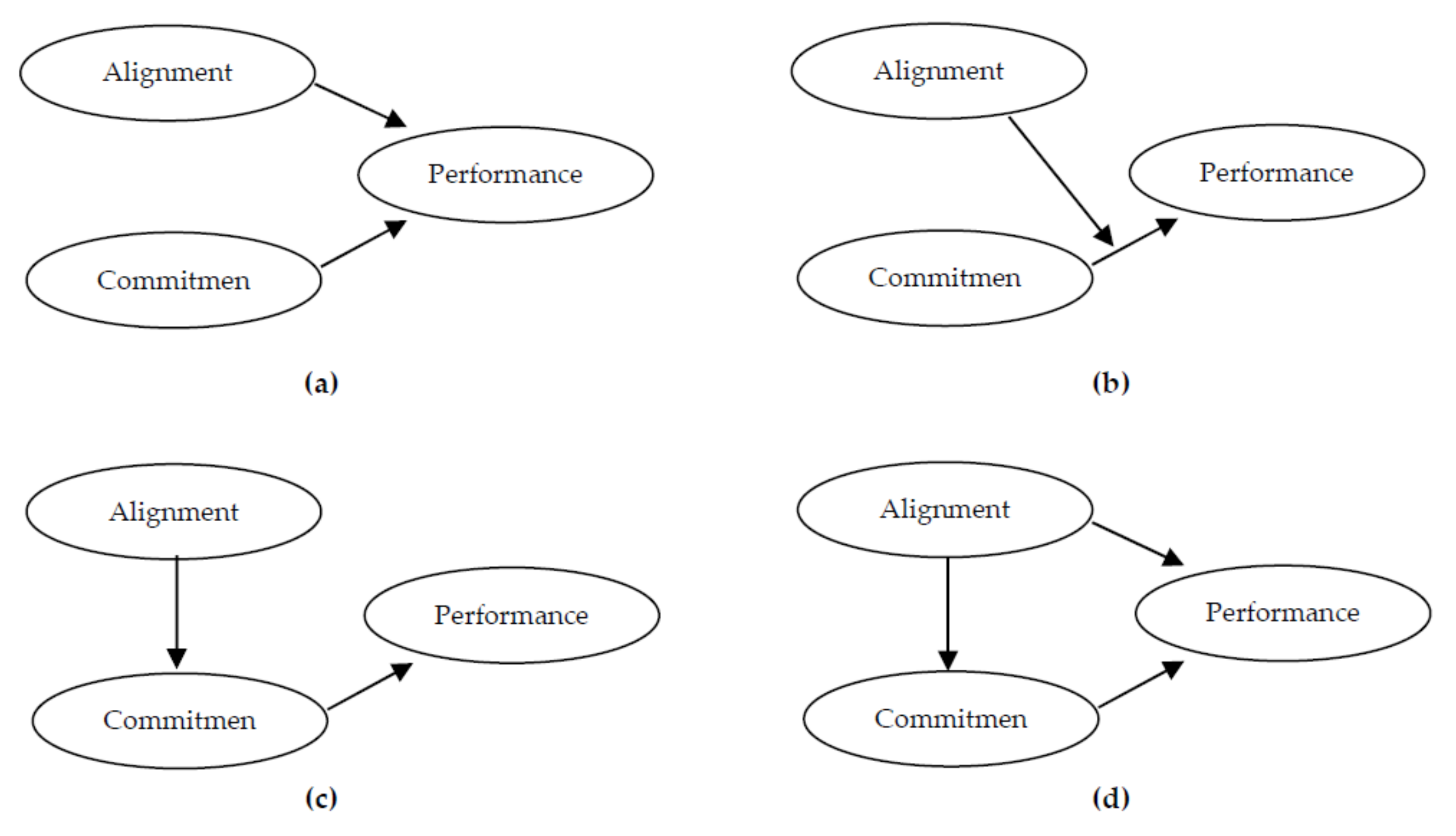

1.2. CSR Commitment, Alignment and Firm Performance

2. Materials and Methods

Conceptualising CSR Orientation

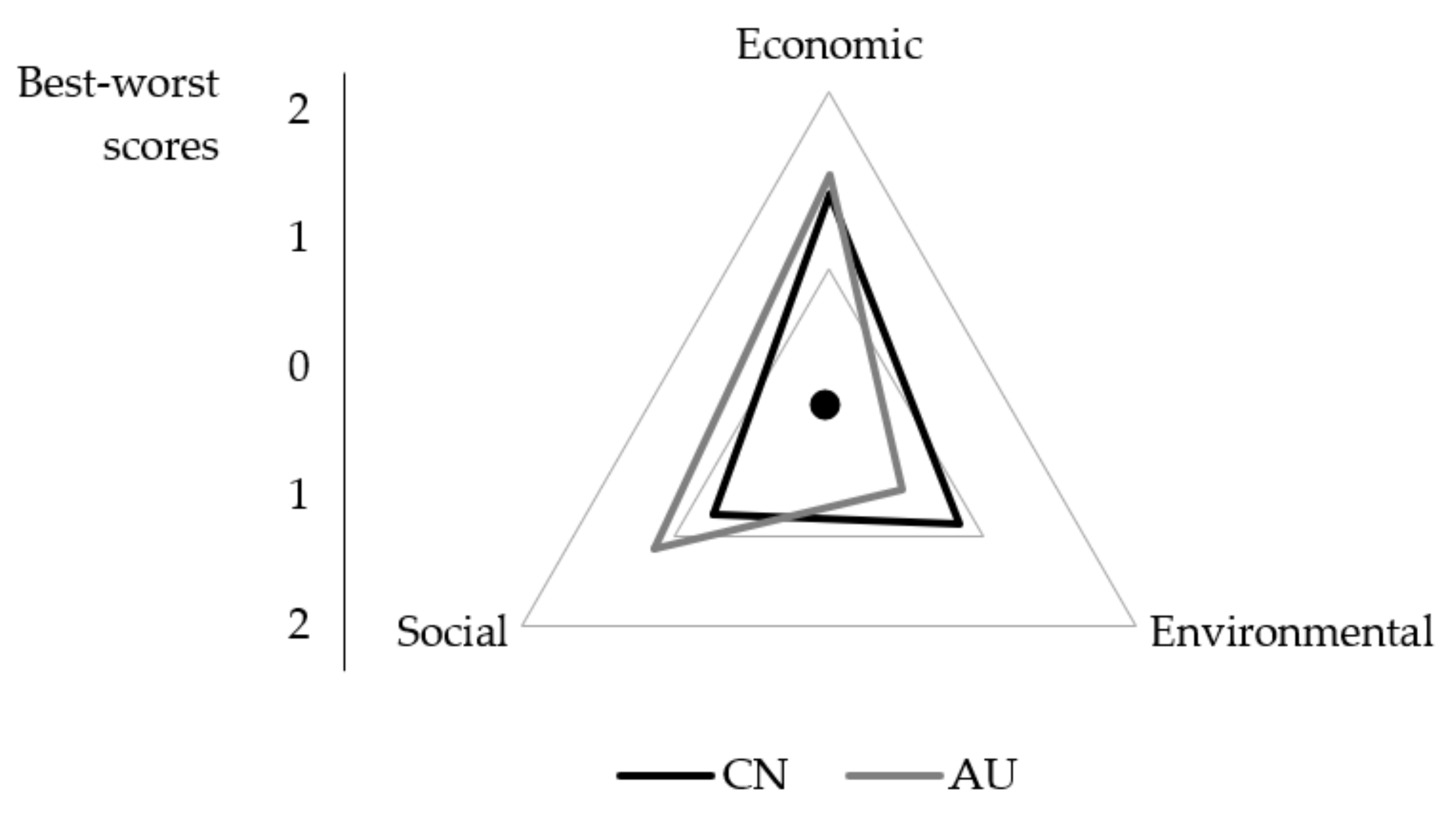

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Implications for Theory

4.2. Implications for Policy and Practice

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Definition of CSR Factors

- Corporate governance: Emphasis on the introduction of policies and strategies to reduce exposure to risk.

- New products/services: Emphasis on the developing and introducing new and innovative products and services.

- Productivity: Emphasis on increasing the net output from existing organizational resources.

- Competitiveness: Emphasis on doing things better than competitors, or by selectively targeting niche markets.

- Profitability: Emphasis on increasing revenue and reducing costs relative to income.

- Ethics (The placement of the “ethics” factor within the economic performance dimension requires some explanation. During the qualitative work the term ethics was generally used in two ways—to represent a specific type of action (e.g., ethical hiring practices, ethical use of technology, etc.), or to describe a broader philosophical commitment to doing business in a responsible way. The decision to place the ethics factor within the economic performance dimension represents the second usage.): Emphasis on conducting business in a just and moral manner.

- Human rights: Emphasis on ensuring that the organization is not complicit with human rights abuses.

- Labor practices: Emphasis on maintaining appropriate labor standards that recognize the right to collective bargaining; and the elimination of all forms of forced, compulsory and child labor.

- Employee relations: Emphasis on eliminating all discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

- Corporate philanthropy: Emphasis on supporting worthwhile social projects through financial and in-kind donations.

- Community engagement: Emphasis on actively engaging with the broader community to ensure that they are informed and aware of the organization’s plans.

- Energy efficiency: Emphasis on using less energy to provide the same level of energy service. An example would be insulating a home to use less heating and cooling energy to achieve the same temperature.

- Emissions reduction: Emphasis on reducing the net pollution generated by an organization’s operations.

- Waste reduction: Emphasis on reducing the volume of waste generated by an organization’s activities through initiatives such as recycling.

- Green technology: Emphasis on the use of technologies that have a comparatively lower environmental impact, or that assist a firm to reduce its environmental impact in other areas of operation.

- Environmental protection: Emphasis on adopting business practices that protect the environment.

Appendix B. Calculation of Best-Worst Scores

Appendix C. Calculation of Alignment

References

- Deery, M.; Jago, L.; Fredline, L. Rethinking social impacts of tourism research: A new research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Bai, E.; Liu, L.; Wei, W. A framework of sustainable service supply chain management: A literature review and research agenda. Sustainability 2017, 9, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Lai, I.K.W.; Tang, H.; Pang, C. Coordination Analysis of Sustainable Dual-Channel Tourism Supply Chain with the Consideration of the Effect of Service Quality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, B.; Quazi, A.; Kriz, A.; Coltman, T. In pursuit of a sustainable supply chain: Insights from Westpac Banking Corporation. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2008, 13, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moggi, S.; Bonomi, S.; Ricciardi, F. Against food waste: CSR for the social and environmental impact through a network-based organizational model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dwyer, L.; Sheldon, P.J. Corporate social responsibility for sustainable tourism, BEST Education Network Think Tank VI, Girona, Spain, 13–16 June 2006. Tour. Rev. Int. 2007, 11, 91–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarnia, E.; Garay, L.; Guevara, A. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the travel supply chain: A literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Elkington, J.; Herman, B. Making Sustainability Work: Best Practices in Managing and Measuring Corporate Social, Environmental and Economic Impacts; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, L.; He, B.-J.; Liu, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, X. Sustainability assessment of cultural heritage tourism: Case study of pingyao ancient city in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rugimbana, R.; Quazi, A.; Keating, B. Applying a consumer perceptual measure of corporate social responsibility: A regional Australian perspective. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2008, 29, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Quazi, A.M.; O’brien, D. An empirical test of a cross-national model of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 25, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbavarira, T.M.; Grimm, C. A systemic view on circular economy in the water industry: Learnings from a Belgian and Dutch case. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Dunfee, T.W. Toward a unified conception of business ethics: Integrative social contracts theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 252–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElAlfy, A.; Palaschuk, N.; El-Bassiouny, D.; Wilson, J.; Weber, O. Scoping the evolution of corporate social responsibility (CSR) research in the sustainable development goals (SDGs) era. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Preston, L.E.; Sachs, S. Managing the extended enterprise: The new stakeholder view. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 45, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvelbar, L.K.; Dwyer, L. An importance–performance analysis of sustainability factors for long-term strategy planning in Slovenian hotels. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadeeva, Z. Translation of sustainability ideas in tourism networks: Some roles of cross-sectoral networks in change towards sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesekam, J.; Norman, J.; Garvey, A.; Betts-Davies, S. Science-based targets: On target? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, B.; Kriz, A. Outbound tourism from China: Literature review and research agenda. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2008, 15, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Song, H.; Huang, G.Q. Tourism supply chain management: A new research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson-Hall, T.D.; Hall, D.C. Redefining Quality in Food Supply Chains via the Natural Resource Based View and Convention Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value: Redefining capitalism and the role of the corporation in society. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.J.; Zou, P.X.; Keating, B. Analysing stakeholder-associated risks in green buildings: A social network analysis method. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2013, 13, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, B. Managing ethics in the tourism supply chain: The case of Chinese travel to Australia. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AusTrade. Discussion Paper: Redesign of Australia’s Approved Destination Status Scheme; Australian Government Publishing: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, G.W.; Laws, E. Tourism development of Australia as a sustained preferred destination for Chinese tourists. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2003, 8, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukal, M.; Werthner, H.; Hoepken, W. An approach to enable interoperability in electronic tourism markets. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Information System (ECIS), Vienna, Austria, 3–5 July 2000; p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Keating, B.W.; Kriz, A.; Heung, V. Chinese outbound tourism: An epilogue. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, B.W.; Huang, S.; Kriz, A.; Heung, V. A systematic review of the Chinese outbound tourism literature: 1983–2012. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.Q.; Song, H.; Zhang, X. A comparative analysis of quantity and price competitions in tourism supply chain networks for package holidays. In Advances in Service Network Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kriz, A.; Keating, B. Doing Business in China: Tips for an Outsider (Lǎowài); Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Huang, G.Q.; Song, H.; Liang, L. Game-theoretic approach to competition dynamics in tourism supply chains. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, S. A sustainable tourism policy research review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keating, B.W.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Solnet, D. Theorizing beyond the horizon: Service research in 2050. J. Serv. Manag. 2018, 29, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quazi, A.; Rahman, Z.; Keating, B. A developing country perspective of corporate social responsibility: A test case of Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy (ANZMAC) Conference, Otago, New Zealand, 3–5 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Quazi, A.; Rugimbana, R.; Muthaly, S.; Keating, B. Corporate social action patterns in contrasting market settings. Australas. Mark. J. 2003, 11, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A.; Pearson, L.J. Determining sustainable tourism in regions. Sustainability 2016, 8, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sigala, M. Customer involvement in sustainable supply chain management: A research framework and implications in tourism. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cho, K.; Park, C.K. Does CSR assurance affect the relationship between CSR performance and financial performance? Sustainability 2019, 11, 5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boar, A.; Bastida, R.; Marimon, F. A systematic literature review. Relationships between the sharing economy, sustainability and sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C.N.; Kalavar, J.M.; Melubo, K. Tourism and community well-being: The case of the Maasai in Tanzania. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 44, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiebel, W.; Pöchtrager, S. Corporate ethics as a factor for success–the measurement instrument of the University of Agricultural Sciences (BOKU), Vienna. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2003, 8, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simpson, W.G.; Kohers, T. The link between corporate social and financial performance: Evidence from the banking industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 35, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschoor, C.C. Best corporate citizens have better financial performance. Strateg. Financ. 2002, 83, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.J.; Coltman, T.; Devinney, T.M.; Keating, B. What drives the choice of a third-party logistics provider? J. Supply Chain Manag. 2011, 47, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coltman, T.R.; Devinney, T.M.; Keating, B.W. Best–worst scaling approach to predict customer choice for 3PL services. J. Bus. Logist. 2011, 32, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, B.W.; Coltman, T.R.; Fosso-Wamba, S.; Baker, V. Unpacking the RFID investment decision. Proc. IEEE 2010, 98, 1672–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richard, P.J.; Coltman, T.R.; Keating, B.W. Designing IS service strategy: An information acceleration approach. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2012, 21, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wokutch, R.E. The Evolution of Social Issues in Management: What’s in, What’s Out, What’s Hot, and What’s Not 1994 SIM Division Chair Address, August 16, 1994, Dallas, Texas. Bus. Soc. 1998, 37, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wokutch, R.E.; Mallot, M.J. Capturing the creation of a field: Documenting the history of social issues in management. Res. Corp. Soc. Perform. Policy 1998, 15, 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Clair, J.A.; Beatty, J.E.; Maclean, T.L. Out of sight but not out of mind: Managing invisible social identities in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wokutch, R.E. Corporate social responsibility Japanese style, revisited. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2014, 56, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R. Purchasing and social responsibility: A replication and extension. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2004, 40, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, J. Government, business, and the self in the United States. In The Debate over Corporate Social Responsibility; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Marley, A.A.; Louviere, J.J. Some probabilistic models of best, worst, and best–worst choices. J. Math. Psychol. 2005, 49, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T.M. Do what consumers say matter? The misalignment of preferences with unconstrained ethical intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, D. Post-Hoc Statistical Power Calculator for Multiple Regression [Software]. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman, N. Performance implications of strategic coalignment: A methodological perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 1990, 27, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaski, J.F.; Nevin, J.R. The differential effects of exercised and unexercised power sources in a marketing channel. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Esposito Vinzi, V. State-of-art on PLS Path Modeling through the Available Software; HEC Paris: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, R. Towards a conceptualization of unethical marketing practices in tourism: A case-study of Australia’s inbound Chinese travel market. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 24, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Sofield, T. Sustainability in Chinese development tourism policies. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1337–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalič, T.; Žabkar, V.; Cvelbar, L.K. A hotel sustainability business model: Evidence from Slovenia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van de Mosselaer, F.; van der Duim, R.; van Wijk, J. Corporate social responsibility in the tour operating industry: The case of Dutch outbound tour operators. In Tourism Enterprises and the Sustainability Agenda across Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Thurstone, L.L. A law of comparative judgment. Psychol. Rev. 1927, 34, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazin, R.; Van de Ven, A.H. Alternative forms of fit in contingency theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 1985, 30, 514–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Australia (AU) | China (CN) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 62% male | 75% male |

| Education | 62% secondary | 57% tertiary |

| Average age | 52 years | 38 years |

| Age of business | 23 years | 20 years |

| Average employees | 17 | 138 |

| Turnover (AUD) | $24.1 million | $7.4 million |

| CSR expenditure | 2% | 9% |

| Construct | Commitment | Performance | Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment | 1.000 | ||

| Performance | 0.529 | 1.000 | |

| Alignment | −0.183 | −0.373 | 1.000 |

| AVE | 0.793 | 0.658 | 1.000 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.920 | 0.884 | 1.000 |

| Cronbach Alpha | 0.869 | 0.823 | 1.000 |

| R2 | 0.359 |

| Predictor | Predicted | DEM | MEM | FMM | PMM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment | Performance | 0.481 *** | 0.491 *** | 0.480 *** | |

| Alignment | Performance | −0.268 *** | −0.396 | −0.371 *** | −0.265 *** |

| Align*Commit | Performance | −0.374 | |||

| Commitment | Alignment | −0.229 | −0.189* | ||

| Control | Country | 0.153 | 0.007 | 0.147 | 0.157 |

| Model fit | R2 | 0.382 | 0.488 | 0.171 | 0.381 |

| PM | 0.113 |

| RQ | Research Question | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | What are the specific factors that drive a firms CSR orientation? | CSR orientation for national and individual profiles was obtained at both the factor and dimension level. Key drivers of CSR orientation in the Australian sample were employee relations, competitiveness, and ethics. The Chinese sample indicated preference for ethics, new product and service development and profit. |

| 2. | Do these factors differ across intermediaries in a geographically distributed tourism supply chain? | CSR orientation was observed to differ significantly at the factor level between operators in Australia and China. Firms in each country were consistent in their prioritization of economic factors over social and environmental factors. Beyond the profit dimension, Chinese firms were observed to be more concerned with the environment, while the Australian firms with social factors. |

| H1. CSR commitment will positively impact on firm performance. | CSR commitment was observed to have a significant and direct impact on firm performance across all of the structural models examined, and this did not vary by country. | |

| H2. CSR alignment will impact the commitment-performance relationship. | Support was found for a partial-mediating influence for alignment on the commitment–performance relationship over either a mediating effect or full mediating effect. In other words, the performance of supply chain intermediaries was best when they were both committed to CSR and aligned with their supply chain partners. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keating, B.W. CSR Commitment, Alignment and Firm Performance: The Case of the Australia-China Tourism Supply Chain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912718

Keating BW. CSR Commitment, Alignment and Firm Performance: The Case of the Australia-China Tourism Supply Chain. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912718

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeating, Byron W. 2022. "CSR Commitment, Alignment and Firm Performance: The Case of the Australia-China Tourism Supply Chain" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912718