1. Introduction

Tourism is globally recognized as a significant industry in job creation, wealth distribution, and local development (World Tourism and Travel Council [WTTC]), [

1]. As primarily associated with the people’s movement along local and international boundaries, tourism promotes the meeting of different nationals, encouraging people to promote social interactions, allowing them to experience positive vibes, and expanding their consciousness. The industry is deemed an agent of economic development [

2], with Comerio and Strozzi [

3] outlining four clusters on the pathways tourism impacts the economy. More importantly, in recent decades, developing countries have been focusing on initiating developments in tourism [

4,

5]. Like other developing countries, the Philippine tourism industry is overgrowing, evident in the contribution to domestic tourism expenditure, comprising the bulk (84%) of the tourist outlay in the country at USD 55 billion in 2019. The strong local tourism expenditure supported domestic opportunity in recent years, accounting for 11.7% of the GDP in 2017 to 12.1% in 2019 [

6]. However, sports tourism has developed only lately as a typology despite its rapid rise. Aside from contributing to the respective sports, the sports tourism industry supports the government and local communities by raising funds and promoting sports activities. Accordingly, it was previously projected that sports tourism would increase from USD 1.41 trillion in 2016 to USD 5.7 trillion in 2021 globally [

7].

The increasing number of sporting events results from the concerted efforts to boost tourism and open up more prospects for development. Getz and Page [

8] argue that hosting sporting events can benefit destinations by improving their exposure and image. It can also open up opportunities for developing tourism-based revenues from those connected to the event, especially the locals, or from outside observers who travel to experience the sporting events [

9]. As its success is associated with gathering crowds, particularly local residents, understanding residents’ opinions is essential for the local government or stakeholders in crafting plans for tourism development [

10,

11]. The role of local support in tourism development is widely discussed in the domain literature. For instance, resistance from the residents may arise in response to the detrimental effects of tourism on the environment and social welfare [

12]. Specifically, in the case of Venice and Barcelona, the resident’s quality of life has been negatively affected by tourism activities; thus, residents are launching campaigns against tourism, which result in undesirable effects on the industry [

13]. Thus, aside from the positive impact tourism activities have on local development, negative consequences have been documented in the literature, which make local support pivotal to tourism planning and development.

A conventional way to promote local support for tourism activities is to secure residents’ satisfaction, largely associated with quality of life, future development, and desire to live in the place [

13]. Residents’ satisfaction is considered a consequence of tourism activities’ economic and social benefits. It is widely claimed that the community must have shared access to any tourism initiatives and be involved in the decision-making process regarding tourism development. This involvement positively influences the residents’ satisfaction and intention to participate in tourism activities [

12]. Yet, some observations show that local residents are not usually involved in the decision-making and micro-management of tourism development (e.g., [

14]). Furthermore, a lack of experience, resources, and interest would unfavorably impact successful entrepreneurial engagements [

15]. Thus, some argue that residents are more likely to focus on the shared social benefits instead of the direct economic advantage of tourism development [

16,

17]. These social benefits may involve a sense of pride and self-actualization resulting from a tourism activity (e.g., hosting a sporting event) [

18].

The relationship between attitude and support for tourism development by the residents has been exhaustively studied with the behavioral constructs of social exchange theory (SET) [

19]. In SET, individuals share resources with the expectation of reciprocity [

20]. SET demonstrates how individuals’ attitudes and behaviors interact with one another [

21] and is considered one of the most influential management theories [

22]. It is regarded as a convenient framework for investigating the different dimensions and directions of attitude among people (e.g., community members) [

23,

24,

25]. Within the tourism domain, the SET framework is widely used to describe the relationship between the residents’ support for tourism, contributions to the community, and future tourism development. Contextually, SET explains the residents’ tendency to support tourism initiatives as they believe the benefits will outweigh the costs [

26]. For instance, locals who have gained more benefits from tourism are more supportive of tourism development and would participate in an exchange interaction for value [

27,

28,

29]. Gursoy et al. [

30] emphasized that residents who view tourism activities as beneficial have more positive attitudes towards future tourism developments. These benefits include enhanced quality of living [

31], increased job opportunities, and improved overall potential for the community [

32]. Several works have extended SET and examined various factors as their theoretical framework in local support (see works of [

16,

33,

34,

35]). SET has been used in varied contexts, including leadership [

36,

37], education [

38], and residents’ perceptions [

39]. Various works in the domain literature utilize SET for local support; however, a significant criticism of SET is its lack of sufficient theoretical precision and limited utility. As argued by Cropanzano et al. [

40], the characteristic of SET that strictly assumes positive support as an immediate consequence of the absence of a lack of support from the actors in the system may not be the case for all.

As SET suggests, social exchange will not occur if neither of the two individuals receives adequate rewards. The assessment of the benefits of the exchange is affected by an individual’s emotions, which SET fails to consider [

41]. Furthermore, the emotions experienced in the exchange process affect the differing perception of the individual’s present and future interactions [

42]. In tourism, there is an existing complex relationship between tourists and residents that SET fails to capture [

41]. Hence, Woosnam and Norman [

43] utilized Durkheim’s theoretical framework of emotional solidarity to measure the significance of residents’ attitudes towards tourism by developing an emotional solidarity scale. Concurrently, emotional solidarity has been adopted in the tourism literature to evaluate the level of familiarity or closeness between residents and tourists (e.g., [

44,

45,

46]). Thus, a close examination of the attitude of residents towards local support for tourism development is of critical importance, especially in an emerging type of tourism (i.e., sports tourism). This relationship has already been established by Woosnam [

47]. However, relying on emotional solidarity alone may pose a challenge in explaining the relationship between the residents’ emotional solidarity with their support for sports tourism and future development. Thus, Erul et al. [

46] considered the supporting effect of the Big Five personality traits on the relationship between emotional solidarity and support for tourism development. As a result, a complete understanding of the residents’ attitude and level of support is achieved. However, no work has yet to integrate this effect of the Big Five personality traits into the local support for sports tourism.

The appeal of sports tourism significantly hinges on the participants’ interest in sports [

48]. This unique characteristic makes it difficult for the residents to appreciate sports events hosted in their community since sports is an uncommon personal interest. Consequently, the need to understand the perspective and attitude of residents, both sports enthusiasts and non-enthusiasts, is deemed pivotal in the literature on sports tourism [

49,

50]. Thus, the main departure of this study is to integrate emotional solidarity and SET to gain a more in-depth understanding of the community-based perspective on future sports tourism development. This study aims to explore the influence of emotional solidarity on the residents’ support for sports tourism and future sports tourism development as an application of SET. In the context of economic and social benefits brought about by sports tourism, communities in developing economies have yet to recognize this potential [

51]. The proposed integrative model is empirically tested in a community of a developing country (i.e., the Philippines) using partial least squares—structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). PLS-SEM is one of the most popular methods to estimate complex models with various constructs and indicators in the structural paths without imposing distributional assumptions on the data [

52]. It is now widely regarded as the most effective analytical tool for evaluating cause-effect models with latent variables. Following the application of PLS-SEM, the insights of the proposed model would inform the design of initiatives to enhance local support for sports tourism development.

The structure of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 details the review of the related literature, while

Section 3 highlights the development of the hypotheses.

Section 4 demonstrates the methodology utilized in the study.

Section 5 presents the results and their implications. Some policy insights are outlined in

Section 6. It ends with concluding remarks, limitations, and future research directions in

Section 7.

5. Discussion

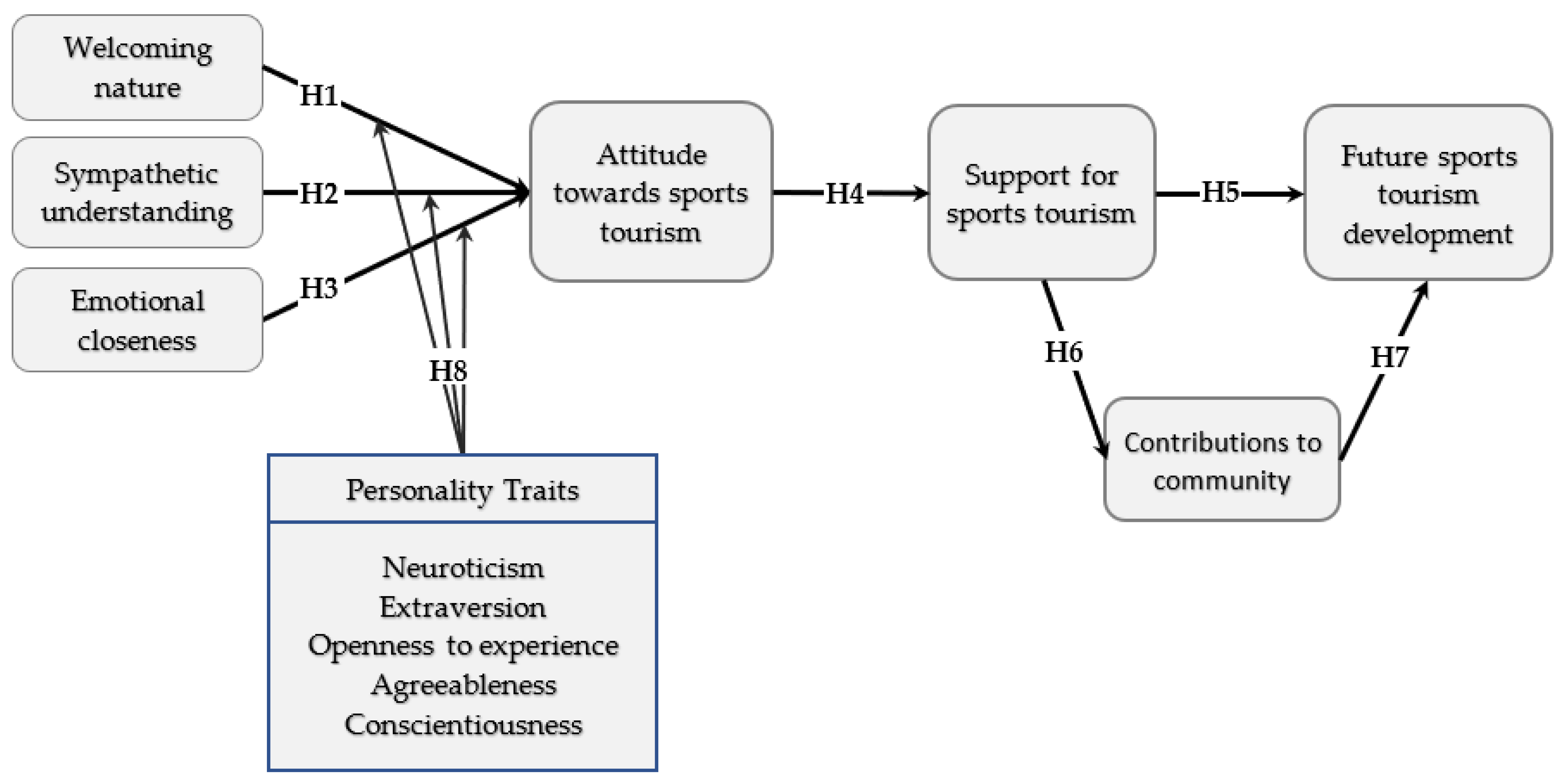

This study examines the proposed structural model that explains future sports tourism development, with theoretical relationships of emotional solidarity construct (i.e., welcoming nature, sympathetic understanding, emotional closeness), attitude towards sports tourism, support for sports tourism, and the mediating role of contributions to the community. In addition, it investigates the moderating effect of personality traits using the Big Five personality traits, specifically agreeableness, neuroticism, openness to experience, conscientiousness, and extraversion. The proposed structural model evaluates the residents’ support for sports tourism and its development in the future, grounded by the works in the literature through the lens of emotional solidarity and the SET. Given that SET provides little possibility for a more intimate interaction between the participants as frameworks such as emotional solidarity can provide [

97], combining emotional solidarity in modeling local support bridges current gaps in the literature. The multigroup analysis provides further insights for sports tourism managers and policymakers by identifying the differences in perspectives on the hypothesized paths among pre-defined groups. Few works in the literature domain investigate these constructs, and the proposed model offers a relatively new perspective on how emotional solidarity augments SET in modeling local support for tourism development, especially in sports tourism being an emerging sector. Conceptually, this work effectively investigates the impact of emotional solidarity in increasing the relevance of SET.

The path coefficients reflected in

Table 4 show that all the hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7) were supported. The significant effect of emotional solidarity construct on attitude toward sports tourism (i.e., H1, H2, H3) supports the insights of Hasani et al. [

44] and Woosnam [

47], although Woosnam [

47] only finds welcoming nature and sympathetic understanding as antecedents of attitude. Further implications of the results are elucidated in the subsequent discussions. The study finds a significant effect of WN on ATST (H1), similar to the work of Lai and Hitchcock [

94]. This implies that residents’ receptiveness to possible changes in their community as a consequence of sports tourism would lead to a positive perspective on related activities. Moreover, SU to ATST (H2) is supported to have a significant relationship. Such a finding is similar to the findings of Woosnam and Aleshinloye [

97], wherein the residents’ positive attitudes toward organizing sports events stem from their willingness to understand the tourists’ sports interests. Meanwhile, EC to ATST (H3) has a significant relationship [

44]. Based on their previous positive interactions with tourists, residents would likely believe they will have the same experience as sports tourists. ATST to SST (H4) is also aligned with the findings of Erul et al. [

46]. Residents’ awareness of the benefits of sports tourism (e.g., economic and social) in their community may result in their willingness to support sporting events. In addition, sports events are seasonal and attract a niche market (common interest groups) which may eventually limit the adverse impacts of tourism in the community. The SST of residents directly affects CC (H5), which supports the claim of Khalid et al. [

142]. Residents’ complete understanding of the significance of sports tourism may result in a positive perception of the opportunities brought about by sports tourism development (e.g., recreational, infrastructural), particularly in improving their quality of life, public service, and overall well-being. Moreover, the relationship of CC to FSTD (H6) is supported in this study, consistent with the work of Erul et al. [

46], which is a direct implication of SET. The residents’ knowledge of the contribution of sports tourism outweighs the costs resulting from their support of FSTD. Residents become receptive to FSTD as they become more aware of the progress that positively impacts them or their families from economically and socially organizing sports tourism. Lastly, the relationship between the residents’ SST and FSTD is supported (H7), strengthening the claim of Erul et al. [

46]. The residents understood that their participation and proactive involvement in sports tourism activities could eventually contribute to the sound decisions of the policymakers. The Big Five personality traits were found to have no moderating effect on WN to ATST, SU to ATST, and EC to ATST. This indicates that the residents’ personality does not affect the influence of WN, SU, and EC on ATST. The residents’ behaviors, cognitions, and emotional patterns (i.e., choices and preferences) have a negligible bearing on the residents’ perception of supporting sports tourism. Non-sports enthusiast residents, for example, may positively support sports tourism and its development for the overall progress of the community. Overall, these findings of the model suggest that locals who are open to tourists and feel connected to them not only have positive attitudes about tourism and a higher degree of support for tourism development, but they also appreciate the benefits that tourism offers to the local community [

47].

The MGA results show a significant difference between the public servants and the local entrepreneurs in their SU towards their ATST (β = 0.217). The result also partially supports the difference between WN to ATST as moderated by BFPT (β = 0.188). As a result, the public servants identified themselves more with the sports tourists and extended more effort into accommodating them. This may be attributed to the nature of their work in the community. In addition, public servants have more appreciation of the contribution of sports tourists to the local economy than local entrepreneurs. This is also similar to the results between public servants and residents, where the WN to ATST of the public servant is also higher compared to the residents as moderated by BFPT. Furthermore, public servants are more involved in the decision-making process regarding tourism development. Between the public servant and the residents, the result supports that there is a significant difference in their relationship of ATST to SST (β = −0.162), SST to CC (β = −0.229), and SU to ATST (β = 0.318). It also partially supports the difference in their WN to ATST moderated by BFPT (β = 0.192). Between the public servant and residents, the resident projects higher ATST to SST with their belief that sports tourism could provide further community growth. Local residents also project more SST to CC with the enjoyment and prestige brought about by organizing sports events that enhance their sense of belongingness in the community. The residents have higher WN to ATST as moderated by BFPT, highlighting that personality traits (e.g., sports enthusiasts) affect the appreciation and support for sports tourism. Between local entrepreneurs and residents, the residents have higher ATST to SST (β = −0.135), which could be attributed to the level of their understanding of the relevance of sports events in the community (e.g., economic) since they have more access to social information and activities. Meanwhile, local entrepreneurs are more focused on their business operations. Furthermore, local entrepreneurs and residents have a different view of SST to CC (β = −0.127), with residents having a higher perception of CC due to their higher degree of involvement with more potential benefits gained from sports events (e.g., economic and social). Overall, not all local entrepreneurs could participate in sports events, which may be attributed to the nature of their business. Moreover, the residents have higher direct WN to ATST (β = −0.24). Thus, residents have more appreciation and sense of community pride with the offering of sports tourism that highlights their locality than local entrepreneurs. This may imply that not all local entrepreneurs directly benefit economically from sports events.

6. Policy Insights

This study’s findings offer insights into the design of policies relevant to sports tourism development. Based on these findings, policymakers and sports tourism managers should focus on the sources influencing the residents’ attitudes and support for sports tourism. In this regard, we focus on the factors of emotional solidarity construct (i.e., welcoming nature, emotional closeness, and sympathetic understanding) as the antecedents of residents’ attitudes. These specific insights are presented in different themes that could be utilized by other communities’ sports tourism development agendas.

With the significance of the welcoming nature of residents in improving their view on support for future sports tourism development, policymakers may design programs that encourage residents to be more receptive to sports tourists. First, they may provide incentives to local entrepreneurs, such as offering discounts on permits and tax incentives for their promotion and active participation in sports events (e.g., sponsorship, member of the organizing committee). It would encourage them to be more involved in sports events and invest in promotional activities. Second, policymakers may also provide financial incentives to local sports organizers (i.e., village organizers, local organizations, or associations) to be more active in organizing exciting and inviting sports events. Third, the local government may integrate organized local tours in strategic tourist areas in the community within the sports event schedule designed to immerse sports tourists in the local culture. For example, the case environment can highlight pottery making, keseo, pinatapi or tapa making, learning about the Karansa festival, and visiting tourist spots. It would boost the residents’ pride in their locality while the tourists feel the locality’s hospitality.

As sympathetic understanding encourages mutual understanding between residents and tourists, the local government may encourage entrepreneurs to sell local products such as delicacies and traditional handicrafts at sports events at discounted charges. It would promote micro- to small-sized businesses to support sports tourism events. They may also offer price incentives to residents who participate in sports events (i.e., creating a separate category for the locals, giving discounts, and offering perks). This would give locals more access to the activities and a better understanding of the sports. For non-sports enthusiast residents, other sports-related activity options may be created for them to feel involved. The government may initiate information drives to educate the locals on the benefits of sports and sports tourism in the community, such as through e-marketing, social media, and other platforms. It may develop an evaluation and monitoring system in the community (before, during, and after sports events) to assess the perceptions of the residents and tourists regarding sports services and product delivery. Such a platform may serve as a basis for future planning and development of sports tourism.

To promote emotional closeness, the local government may also design recognition programs for locals, either public servants, entrepreneurs, or the general community, who delivered quality service and offered excellent products during sports events to boost their morale and to look forward to providing better service in the future. It may also promote local participation through assigning relevant roles to residents during sports events, including peace and order, aid in traffic flow, tourist assistance desk, tour guides, and membership in organizing committees. Cultural integration of sports may be encouraged through events in the community, which will require organizers to embed the local culture. For instance, Karansa cycling in Danao City may be organized that would highlight the traditional Karansa dance during the event. This initiative may revive the declining local industry, encouraging more opportunities for social interactions between residents and tourists. The local government may require organizers to hold pre-event orientation to sports tourists and participants on local culture and customs, as well as relevant local policies to catalyze positive relationships.

To strengthen community contribution, employment opportunities and incentives may be offered to local micro-businesses and start-ups relating to sports. This would generate revenues and taxes for investments in infrastructure. The community may organize sports events for a cause (i.e., run for a cause for residents with cancer) targeting a specific marginalized sector in the community by allocating a certain percentage of the proceeds based on agreements. Local teams may be organized on particular sports to encourage residents who are sports enthusiasts via the social interactions that they would eventually form. Recreational facilities may be developed to promote the residents’ interest in sports and an active lifestyle. The government may support the maintenance of existing sports facilities (e.g., sports complexes, swimming pools, and gyms) and provide a safe environment for sports activities, such as safe cycling lanes and proper venues for motor cross, among others.

7. Conclusions and Future Works

Despite the popularity of SET in evaluating local support for tourism development, some of its drawbacks hinder its application. The current literature explores the role of emotional solidarity in augmenting the relevance of SET. However, identifying possible antecedents of locals’ attitudes, given their support for tourism development within the SET framework, remains a gap. This work offers two contributions. First, it proposes an integration of emotional solidarity constructs and SET in modeling local support. Second, it examines the antecedents of local support in sports tourism. In the proposed model, the three variables of emotional solidarity, namely, welcoming nature (WN), sympathetic understanding (SU), and emotional closeness (EC), are considered antecedents of local attitudes within SET. Their relationships were hypothesized to be moderated by the Big Five personality traits (BFPT) (i.e., openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism). Furthermore, the relationship between residents’ attitudes (ATST) and support (SST) towards sports tourism is also explored. Meanwhile, the social exchange integrated from SET is characterized by the relationship among SST, community contributions (CC), and future sports tourism development (FSTD). A mediating effect of CC between SST and FSTD is also considered. With PLS-SEM, the proposed integrated model is empirically tested in a case study of 1004 participants.

Using the SmartPLS algorithm, the following relationships are significantly supported. First, the emotional solidarity constructs, including welcoming nature, sympathetic understanding, and emotional closeness, are found to affect the attitude of residents in their support of sports tourism. It implies that the emotional bonds resulting from shared beliefs, engagement in similar activities, and interactions between sports tourists and locals during sporting events have an important role in residents’ view of sports tourism. This finding supports those in the literature. Secondly, residents’ support can be predicted by their attitude or view on sports tourism, and such support could be directly translated into the provision of future development agenda. As such, the optimistic view of residents on sports tourism would likely increase their support and future needed support. Third, a partial mediating effect of community contribution on the relationship between support of sports tourism and future sports tourism development is observed in this study. This finding effectively supports the provision of SET, which suggests that the degree of residents’ view of future development initiatives is influenced by their perception of the contributions they or their community obtains from those initiatives. Fourth, the study finds no moderating effect of Big Five personality traits on the relationship between emotional solidarity constructs and residents’ views on sports tourism. It indicates that the emotional interactions between sports tourists and locals are independent of their personality traits. Lastly, the degrees of the factors that predict future sports tourism development are likely dependent on the groups among local residents. In this study, the three groups comprising public servants, local entrepreneurs, and residents have differing views on how they support future development agendas. Based on these findings, the following policy insights are developed: (a) incentive programs for local entrepreneurs, sports organizers, and residents, (b) cultural integration to sports events, (c) dissemination initiatives of relevant event information, and (d) infrastructure support.

Some limitations are particularly obvious. First, the study focuses on assessing the residents’ attitude toward sports tourism and future sports tourism development in Danao City, central Philippines, with the same conditions as in other developing countries. Future cross-sectional studies may replicate the same agenda in other regions to establish the theoretical insights identified in this work. A replicate survey with a larger and more geographically varied sample is warranted for future work. Second, the study only focuses on sports tourism and its development, not the entire tourism sector. The role of emotional solidarity within the SET framework may be examined in other tourism sectors. Third, the residents (i.e., being the primary study participants) were not screened according to the years they have lived in the community. Future work may evaluate the moderating role of the length of residency in our hypothesized model. Finally, an investigation of the residents’ support using other theoretical frameworks could also be undertaken.