Nexus between Environmental Consciousness and Consumers’ Purchase Intention toward Circular Textile Products in India: A Moderated-Mediation Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

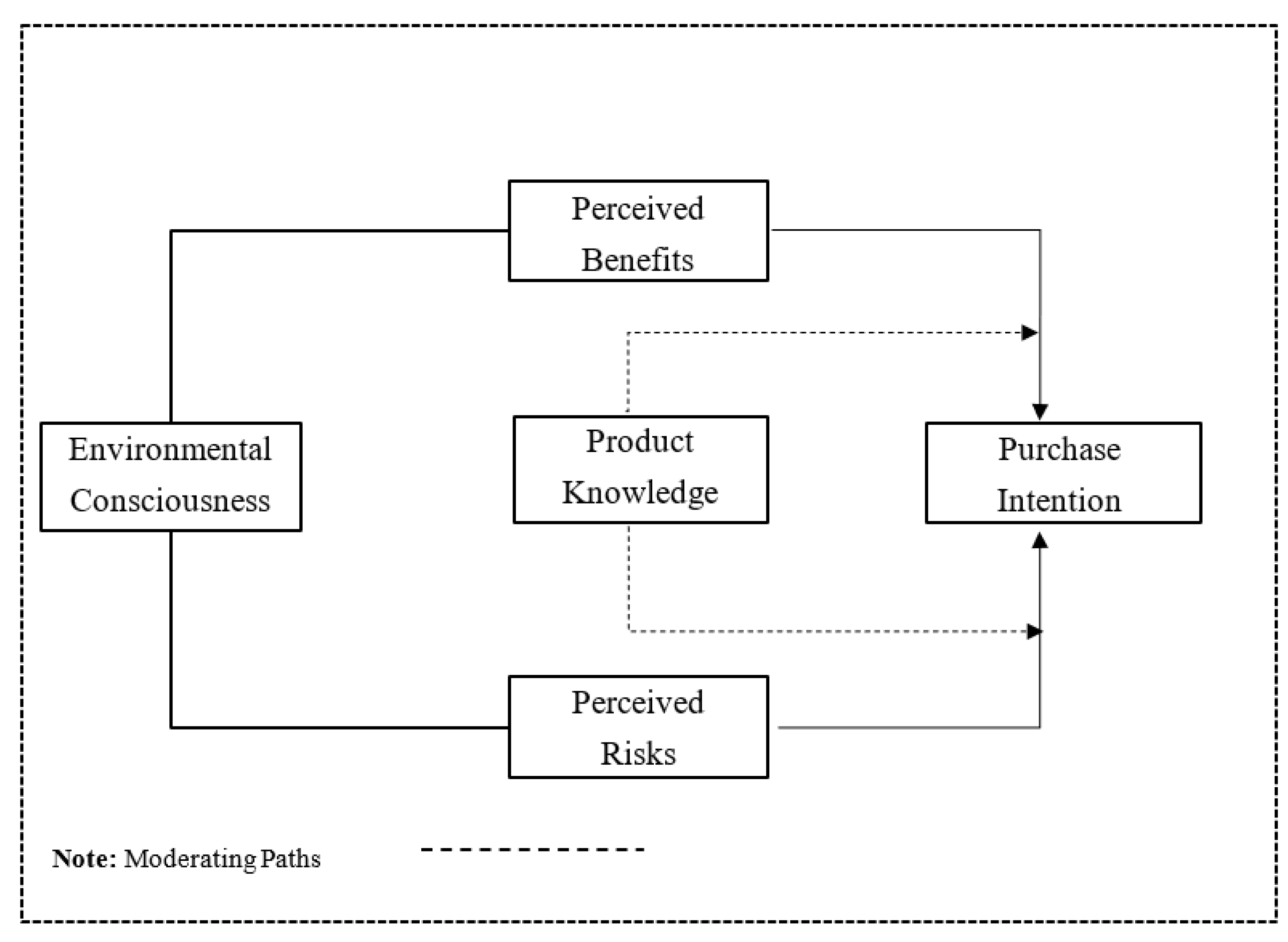

2. Theory and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Environmental Consciousness (EC) and Consumers’ Purchase Intention (PI)

2.2. Perceived Risks (PR) and Consumers’ Purchase Intention (PI)

2.3. Perceived Benefits (PB) and Consumers’ Purchase Intention (PI)

2.4. Perceived Risks (PR) and Perceived Benefits (PB) as the MEDIATOR between Environmental Consciousness (EC) and Purchase Intention (PI) Relationship

2.5. Product Knowledge (PK) as the Moderator on the Relationships between Perceived Risks (PR), Perceived Benefits (PB), and Purchase Intention (PI)

2.6. Conditional Mediation Effect of Perceived Risk and Benefits on the Direct Relationship between Environmental Consciousness (EC) and Purchase Intention (PI) with Product Knowledge (PK) as the Moderator

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Development

3.2. Participants, Pilot Study, and Main Survey

3.3. Data Preparation

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model: Fit Indices, Reliability, and Validity

4.2. Direct Effects

4.3. Indirect Effects (Mediation Analysis)

4.4. Interaction Effects (Moderation Analysis)

4.5. Conditional Indirect Effects (Moderated-Mediation Analysis)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire Items with Their CFA Loadings and Source of Adoption

| Construct Name and Measurement Item | CFA Loadings |

| Environmental Consciousness (EC) (Source: Suki, 2016; Singhal et al., 2019 [20]; Schlegelmilch et al., 1996) | |

| “I am willing to make extraordinary efforts to purchase circular textile products to protect the environment.” | 0.717 |

| “Given a choice, I will prefer to purchase a circular textile product because it is less harmful to the environment.” | 0.830 |

| “I will purchase circular textile products because it contributes towards the sustainability of the environment.” | 0.791 |

| “I would prefer circular textile products over fresh textile products because it helps in limiting environmental pollution.” | 0.751 |

| Perceived Risks (PR) (Source: Singhal et al., 2019 [20]; Wang et al., 2013 [32]) | |

| “I sam afraid that the frequent maintenance of circular textile products will waste my time and money.” | 0.715 |

| “I apprehend that circular textile products will have poor performance.” | 0.826 |

| “I fear that the use of circular textile products might lead to skin issues/problems.” | 0.774 |

| Perceived benefits (PB) (Source: Singhal et al., 2019 [20]; Forsythe et al., 2006) | |

| “I will buy circular textile products because of their lower price”. | 0.782 |

| “I will purchase circular textile products because I will be able to buy more textile products at a low price”. | 0.783 |

| “I will purchase circular textile products because they will be available at a discount”. | 0.818 |

| “I will purchase circular textile products if I get an exchange offer in return for my used textiles”. | 0.733 |

| Product knowledge (PK) (Source: Michaud & Llerena, 2011 [3]; Wang et al., 2013 [32]) | |

| “I am familiar with the remanufacturing process of circular textile products”. | 0.742 |

| “I am familiar with the performance and features of circular textile products”. | 0.868 |

| “I am familiar with the price level of circular textile products”. | 0.797 |

| “I am familiar with the quality warranty of remanufactured products”. | 0.853 |

| Purchase Intention towards CTPs (Source: Calvo-Porral & Lévy-Mangin, 2020; Singhal et al., 2019 [20]) | |

| “I will buy circular textile products in the future”. | 0.793 |

| “I am likely to buy circular textile products”. | 0.758 |

| “I will continue buying circular textile products”. | 0.781 |

| “I am excited to buy circular textile products”. | 0.789 |

References

- India Brand Equity Foundation. TEXTILES AND APPAREL. 2022. Available online: https://www.ibef.org/download/1659942959_Textiles_and_Apparel-PPT-June_2022.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Hari, D.; Mitra, R. Circular Textile and Apparel in India Policy Intervention Priorities and Ideas. New Delhi: Centre for Responsible Business (CRB). 2022. Available online: https://c4rb.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Circular_Apparel_Status_Paper_140422.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Michaud, C.; Llerena, D. Green Consumer Behaviour: An Experimental Analysis of Willingness to Pay for Remanufactured Products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConocha, D.M.; Speh, T.W. Remarketing: Commercialization of remanufacturing technology. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 1991, 6, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Raichur, V.; Skerlos, S.J. Economic and environmental assessment of automotive remanufacturing: Alternator case study. Int. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Conf. 2008, 48517, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, T. Circular Textiles: An Urgent Call for Shift. Available online: https://www.indiaretailing.com/2022/02/08/fashion/circular-textiles-an-urgent-call-for-shift/ (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Steinhilper, R. Recent trends and benefits of remanufacturing: From closed loop businesses to synergetic networks. In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Environmentally Conscious Design and Inverse Manufacturing, Tokyo, Japan, 11–15 December 2001; pp. 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maples, G.E.; Heady, R.B.; Zhu, Z. Parts remanufacturing in the oilfield industry. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2005, 105, 1070–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide, V.D.R., Jr.; van Wassenhove, L.N. The Evolution of Closed-Loop Supply Chain Research. Oper. Res. 2009, 57, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cao, J.; Kumar, S. Government regulation and enterprise decision in China remanufacturing industry: Evidence from evolutionary game theory. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2021, 6, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krikke, H.; Hofenk, D.; Wang, Y. Revealing an invisible giant: A comprehensive survey into return practices within original (closed-loop) supply chains. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 73, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.H. Supply chain-based barriers for truck-engine remanufacturing in China. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2014, 68, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaud, D.; Laperche, B. Circular Economy, Industrial Ecology and Short Supply Chain; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, M.E.; Toktay, L.B. The effect of competition on recovery strategies. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2006, 15, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasu, A.; Sarvary, M.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Remanufacturing as a marketing strategy. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1731–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Parra, B.; Rubio-Lacoba, S.; Vicente-Molina, A. An approximation to the remanufactured electrical and electronic equipment consumer. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Industrial Management, Istanbul, Turkey, 3–6 July 2012; pp. 433–440. [Google Scholar]

- Muranko, Z.; Andrews, D.; Newton, E.J.; Chaer, I.; Proudman, P. The pro-circular change model (P-CCM): Proposing a framework facilitating behavioural change towards a circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Prakash, G.; Kumar, G. Does environmentally responsible purchase intention matter for consumers? A predictive sustainable model developed through an empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, D.; Jena, S.K.; Tripathy, S. Factors influencing the purchase intention of consumers towards remanufactured products: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7289–7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, D.; Tripathy, S.; Jena, S.K. Acceptance of remanufactured products in the circular economy: An empirical study in India. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hazen, B.; Mollenkopf, D. Consumer value considerations and adoption of remanufactured products in closed-loop supply chains. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Li, J.; Song, J. Determinants of consumers’ remanufactured products purchase intentions: Evidence from China. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 2368–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hazen, B. Consumer product knowledge and intention to purchase remanufactured products. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 181 Pt B, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, A.; Ok, C. The effects of consumers’ perceived risk and benefit on attitude and behavioral intention: A study of street food. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahjudi, D.; Gan, S.; Anggono, J.; Tanoto, Y. Factors Affecting Purchase Intention of Remanufactured Short Life-Cycle Products. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 19, 415–428. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huscroft, J.R.; Hazen, B.T. and Zhang, M. Green information, green certification and consumer perceptions of remanufactured automobile parts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 128, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide, V.D.R., Jr.; Li, J. The Potential for Cannibalization of New Products Sales by Remanufactured Products. Decis. Sci. J. 2010, 41, 547–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, B.T.; Overstreet, R.E.; Jones-Farmer, L.A.; Field, H.S. The role of ambiguity tolerance in consumer perception of remanufactured products. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weelden, E.; Mugge, R.; Bakker, C. Paving the way towards circular consumption: Exploring consumer acceptance of refurbished mobile phones in the Dutch market. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, J.; Amini, M.; Banerjee, P.; Gupta, R. Drivers of Consumer Purchase Intentions for Remanufactured Products: A Study of Indian Consumers Relocated to the USA. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2015, 18, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Parra, B.; Rubio, S.; Vicente-Molina, M.-A. Key drivers in the behavior of potential consumers of remanufactured products: A study on laptops in Spain. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 85, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wiegerinck, V.; Krikke, H.; Zhang, H. Understanding the purchase intention towards remanufactured product in closed-loop supply chains: An empirical study in China. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 866–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, J.; Testa, F.; Rizzi, F. The more I care, the less I will listen to you: How information, environmental concern and ethical production influence consumers’ attitudes and the purchasing of sustainable products. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, E.R.; Costa, M.F.; Oliveira, K.K. Persuasive communication on the internet via Youtube: Is it possible to increase environmental concern and consumer involvement with sustainability? Theory Pract. Admin 2015, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C. In the eye of the storm: Exploring the introduction of environmental issues in the production function in Brazilian companies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2010, 48, 6315–6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seles, B.M.R.P.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Latan, H.; Roubaud, D. Do environmental practices improve business performance even in an economic crisis? Extending the win-win perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 163, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W.T., Jr.; Cunningham, W.H. The socially conscious consumer. J. Mark. 1972, 36, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leaniz, P.M.G.; Crespo, A.H.; Lopez, R.G. Customer responses to environmentally certified hotels: The moderating effect of environmental consciousness on the formation of behavioral intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.B.; Costa, C.S.R.; Felix, G.R. Guilt and pride emotions and their influence on the intention of purchasing green products. Consum. Behav. Rev. 2019, 3, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M. Ethical consumption intentions and choice behavior towards organic food. Moderation role of buying and environmental concerns. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Collins, A. Guest editorial: Perspectives on sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Teiga, N.; Oliveira-Brochado, F. The ecological conscious consumer behaviour: Are the activists different? . Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe, R. Is social psychological model sufficient: Empirical research gaps for understanding green consumer attitudinal behavior. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2012, 1, 28–54. [Google Scholar]

- Aagerup, U.; Nilsson, J. Green consumer behavior: Being good or seeming good? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: The case of organic food. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perceived risk, trust, and democracy. Risk Anal. 1993, 13, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Gotlieb, J.; Marmorstein, H. The moderating effects of message framing and source credibility on the price-perceived risk relationship. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.C.; Tseng, Y.F. Research note: E-store image, perceived value and perceived risk. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Cortimiglia, M.N. Influence of perceived value on purchasing decisions of green products in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 110, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Drew, J.H. A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, M.D.A.; Subramanian, N.; Liu, C.; Shu, C. Viability of remanufacturing practice: A strategic decision making framework for Chinese auto-parts companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 105, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollenkopf, D.; Stolze, H.; Tate, W.L.; Ueltschy, M. Green, lean, and global supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 14–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Shankar, K.M.; Kannan, D. Application of fuzzy analytic network process for barrier evaluation in automotive parts remanufacturing towards cleaner production–a study in an Indian scenario. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.K.; Sarmah, S.P. Price and service co-opetiton under uncertain demand and condition of used items in a remanufacturing system. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 173, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, J.; Li, B. and Wang, Z. Trade-off between remanufacturing and recycling of WEEE and the environmental implication under the Chinese fund policy. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.F.; Rich, S.U. Perceived risk and consumer decision-making—the case of telephone shopping. J. Mark. Res. 1964, 1, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Paiella, M. The Role of Risk Aversion in Predicting Individual Behaviors. SSRN 608262. 2004. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=608262 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Jacoby, J.; Kaplan, L.B. The Components of Perceived Risk; special volumes; Association for Consumer Research: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972; pp. 382–393. [Google Scholar]

- Tarabieh, S.M.Z.A. The impact of greenwash practices over green purchase intention: The mediating effects of green confusion, Green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wu, Y.J.; Tsai, H.; Li, Y. Top management teams’ characteristics and strategic decision-making: A mediation of risk perceptions and mental models. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiang, P.; Zhang, R.; Chen, D.; Ren, Y. Mediating effect of risk propensity between personality traits and unsafe behavioral intention of construction workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, A. The influence of AI word-of-mouth system on consumers’ purchase behaviour: The mediating effect of risk perception. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2022, 39, 516–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Vasantha, D.S.; Sarika, P. Effect of social influence on intention to use mobile wallet with the mediating effect of promotional benefits. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2020, 12, 3003–3019. [Google Scholar]

- Ponnapureddy, S.; Priskin, J.; Vinzenz, F.; Wirth, W.; Ohnmacht, T. The mediating role of perceived benefits on intentions to book a sustainable hotel: A multi-group comparison of the Swiss, German and USA travel markets. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1290–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.; Mohd Mokhtar, S.S. The Actual Purchase of Herbal Products in Malaysia: The Moderating Effect of Perceived Benefit. European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences. In Proceedings of the International Soft Science Conference, Morioka, Japan, 23–25 October 2019; 2019; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, C.; Baber, H.; Kumar, P. Examining the moderating effect of perceived benefits of maintaining social distance on e-learning quality during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2021, 49, 532–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwikael, O.; Pathak, R.D.; Singh, G.; Ahmed, S. The moderating effect of risk on the relationship between planning and success. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozukara, E.; Ozyer, Y.; Kocoglu, I. The Moderating Effects of Perceived Use and Perceived Risk In Online Shopping. J. Glob. Strateg. Manag. 2014, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, M.; Liu, X.; Yang, J. Why should I pay for e-books? An empirical study to investigate Chinese readers’ purchase behavioural intention in the mobile era. Electron. Libr. 2017, 35, 472–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Chinen, K.; Endo, H. Comparison of US and Japanese consumers’ perceptions of remanufactured auto parts. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 966–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chen, C. The influence of the country-of-origin image, product knowledge and product involvement on consumer purchase decisions: An empirical study of insurance and catering services in Taiwan. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Sherrell, D.L. The influence of product knowledge and brand name on internal price standards and confidence. Psychol. Mark. 1993, 10, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.Z.; Wildt, A.R. Price, product information, and purchase intention: An empirical study. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.E.; Innis, D.E. The effects of product knowledge on the evaluation of warranteed brands. Psychol. Mark. 1996, 13, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Goutaland, C. How intangibility affects perceived risk: The moderating role of knowledge and involvement. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, W.; Lund, R.T. The Remanufacturing Industry: Anatomy of a Giant; Department of Manufacturing Engineering; Boston University: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pituch, K.A.; Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences: Analyses with SAS and IBM’s SPSS; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, G.; Singh, P.; Yadav, R. Application of consumer style inventory (CSI) to predict young Indian consumer’s intention to purchase organic food products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Printice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Education International: New Jersey, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton, B.; Muthen, B.; Alwin, D.F.; Summers, G.F. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociol. Methodol. 1977, 8, 84–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Miles, J.N.V. Effects of sample size, model specification and factor loadings on the GFI in confirmatory factor analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1998, 25, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Jia, X. Refurbished or remanufactured?—An experimental study on consumer choice behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, D.G.K.; Weerasinghe, D. Towards circular economy in fashion: Review of strategies, barriers and enablers. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.; Moreira, N.; Ometto, A. Role of consumer mindsets, behaviour, and influencing factors in circular consumption systems: A systematic review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Jung, H.; Lee, Y. Consumers’ Value and Risk Perceptions of Circular Fashion: Comparison between Secondhand, Upcycled, and Recycled Clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuah, A.; Wang, P. Circular economy and consumer acceptance: An exploratory study in East and Southeast Asia. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretner, G.; Darnall, N.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F. Are consumers willing to pay for circular products? The role of recycled and second-hand attributes, messaging, and third-party certification. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 175, 105888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.M.; Heinzel, T. Human perceptions of recycled textiles and circular fashion: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Shamsi, M. Need of post-consumer textile waste management via circular economy. Int. J. Mod. Trends Sci. Technol. 2020, 6, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Less than 20 years | 56 | 13.70 |

| 20–30 years | 210 | 51.30 | |

| 31–40 years | 80 | 19.60 | |

| Above 40 years | 63 | 15.40 | |

| Gender | Male | 230 | 56.20 |

| Female | 179 | 43.70 | |

| Education | Up to intermediate | 56 | 13.70 |

| Graduate | 205 | 50.10 | |

| Post-graduate and above | 148 | 36.20 | |

| Monthly income | Below ₹ 30,000 | 222 | 54.30 |

| Between ₹ 30,001–60,000 | 112 | 27.40 | |

| Between ₹ 60,001–90,000 | 35 | 8.60 | |

| Above ₹ 90,000 | 40 | 9.80 | |

| Awareness of CTP? | Yes | 266 | 65.00 |

| No | 143 | 35.00 | |

| Purchased CTP before? | Yes | 147 | 35.90 |

| No | 262 | 64.10 |

| Model | CMIN/DF | GFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA Model | 1.808 | 0.953 | 0.969 | 0.975 | 0.045 |

| Recommended Value | Acceptable Range [1,2,3,4] | ≥0.90 | ≥0.95 | ≥0.95 | <0.07 |

| [87] | [88] | [89] | [89] | [90] | |

| Variable Name | No of items | Alpha (α) | CR | AVE | |

| Purchase intention | 4 | 0.874 | 0.881 | 0.609 | |

| Environmental consciousness | 4 | 0.842 | 0.856 | 0.596 | |

| Perceived risks | 3 | 0.825 | 0.833 | 0.594 | |

| Perceived benefits | 4 | 0.863 | 0.871 | 0.607 | |

| Product knowledge | 4 | 0.845 | 0.851 | 0.664 | |

| Variable Name | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | PI | EC | PR | PB | PK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase intention | 5.491 | 1.126 | −0.227 | 0.756 | 0.780 | ||||

| Environmental consciousness | 5.747 | 1.098 | 0.099 | −0.752 | 0.545 ** | 0.772 | |||

| Perceived risks | 3.930 | 1.408 | −0.424 | −0.404 | −0.433 ** | −0.446 ** | 0.771 | ||

| Perceived benefits | 4.979 | 1.323 | −0.680 | 0.151 | 0.486 ** | 0.48 ** | −0.364 ** | 0.779 | |

| Product knowledge | 5.439 | 1.050 | −0.692 | 0.432 | 0.538 ** | 0.546 ** | −0.405 ** | 0.460 ** | 0.815 |

| Variable Name | EC | PI | PR | PB | PK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental consciousness | |||||

| Purchase intention | 0.776 | ||||

| Perceived risks | 0.182 | 0.211 | |||

| Perceived benefits | 0.418 | 0.395 | 0.212 | ||

| Product knowledge | 0.646 | 0.623 | 0.141 | 0.565 |

| Independent Variables | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Conditional Indirect Effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On PI | On PI via PR | On PI via PB | On PI via PR | On PI via PB | |||

| At low PK (−1 SD) | At high PK (+1 SD) | At low PK (−1 SD) | At high PK (+1 SD) | ||||

| Environmental consciousness | 0.413 *** | −0.091 ** | 0.113** | −0.139 ** | −0.055 NS | 0.084 ** | 0.146 ** |

| Perceived risks | −0.276 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Perceived benefits | 0.389 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| PR*PK (Interaction effect) | −0.084 ** | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| PB*PK (Interaction effect) | 0.109 ** | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| R2 | 0.421 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shamsi, M.A.; Chaudhary, A.; Anwar, I.; Dasgupta, R.; Sharma, S. Nexus between Environmental Consciousness and Consumers’ Purchase Intention toward Circular Textile Products in India: A Moderated-Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142012953

Shamsi MA, Chaudhary A, Anwar I, Dasgupta R, Sharma S. Nexus between Environmental Consciousness and Consumers’ Purchase Intention toward Circular Textile Products in India: A Moderated-Mediation Approach. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):12953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142012953

Chicago/Turabian StyleShamsi, Mushahid Ali, Asiya Chaudhary, Imran Anwar, Rajarshi Dasgupta, and Sachin Sharma. 2022. "Nexus between Environmental Consciousness and Consumers’ Purchase Intention toward Circular Textile Products in India: A Moderated-Mediation Approach" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 12953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142012953

APA StyleShamsi, M. A., Chaudhary, A., Anwar, I., Dasgupta, R., & Sharma, S. (2022). Nexus between Environmental Consciousness and Consumers’ Purchase Intention toward Circular Textile Products in India: A Moderated-Mediation Approach. Sustainability, 14(20), 12953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142012953