Youth’s Entrepreneurial Intention: A Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis of the Factors Influencing Greek HEI Students in Time of Crisis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

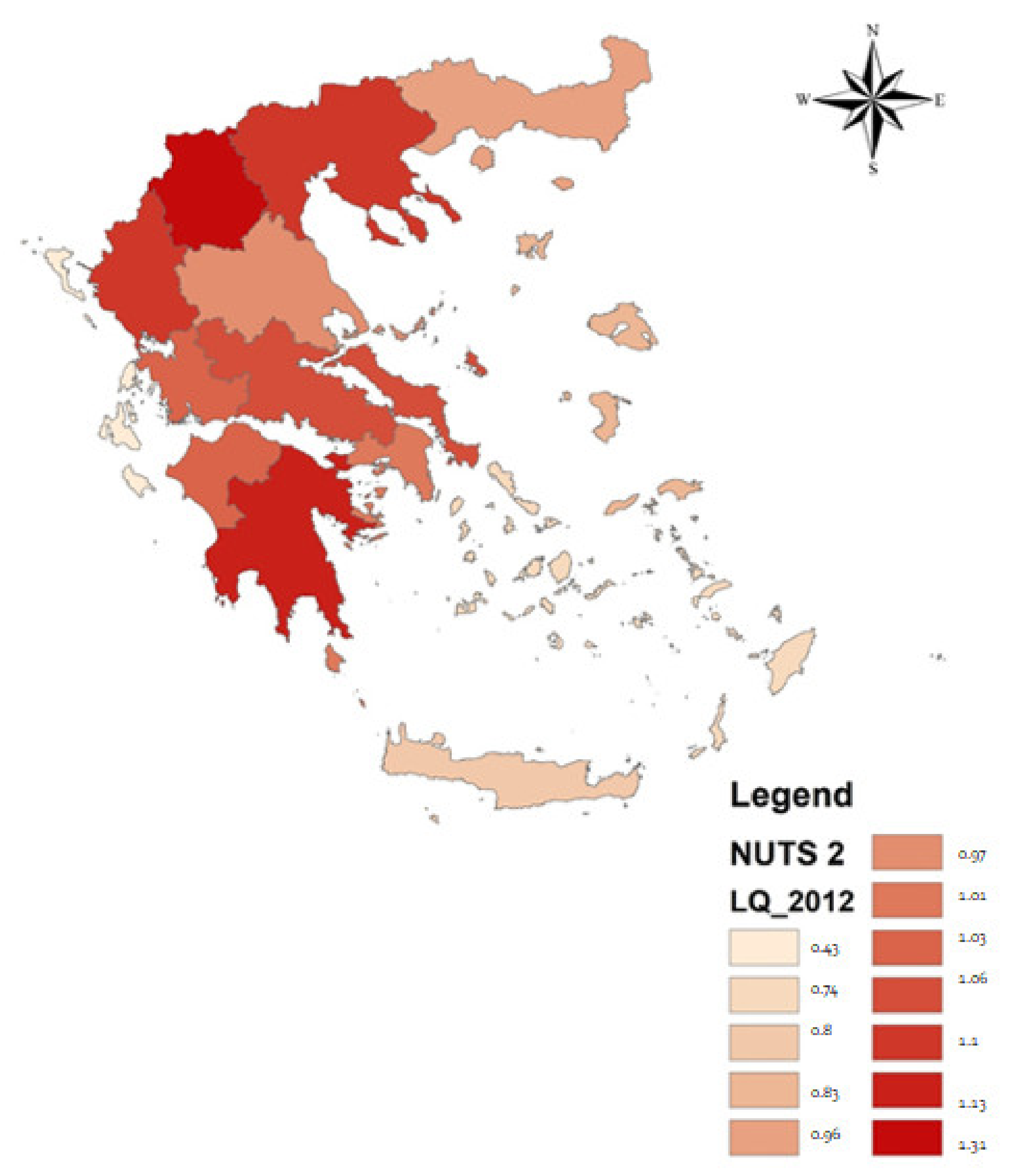

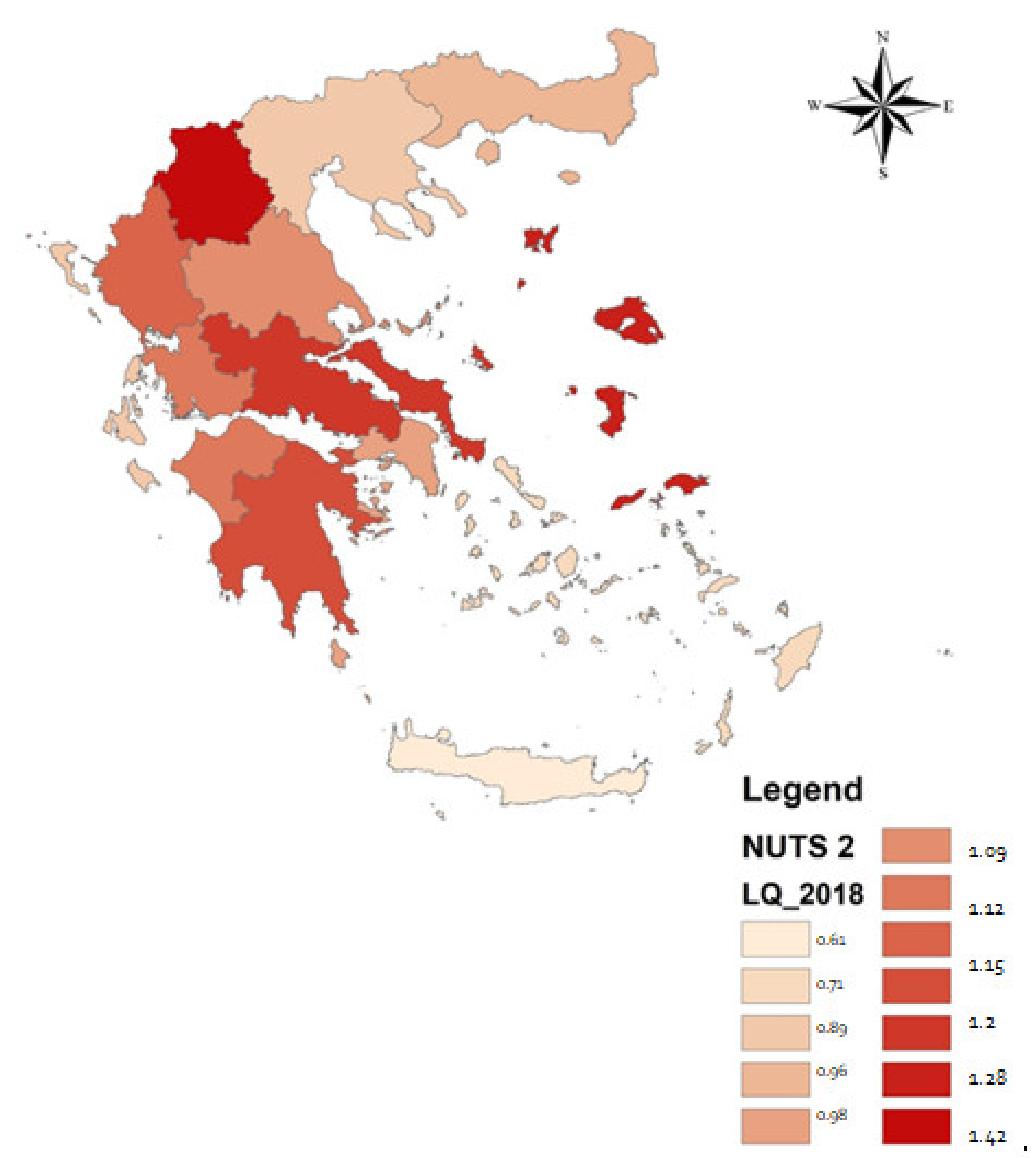

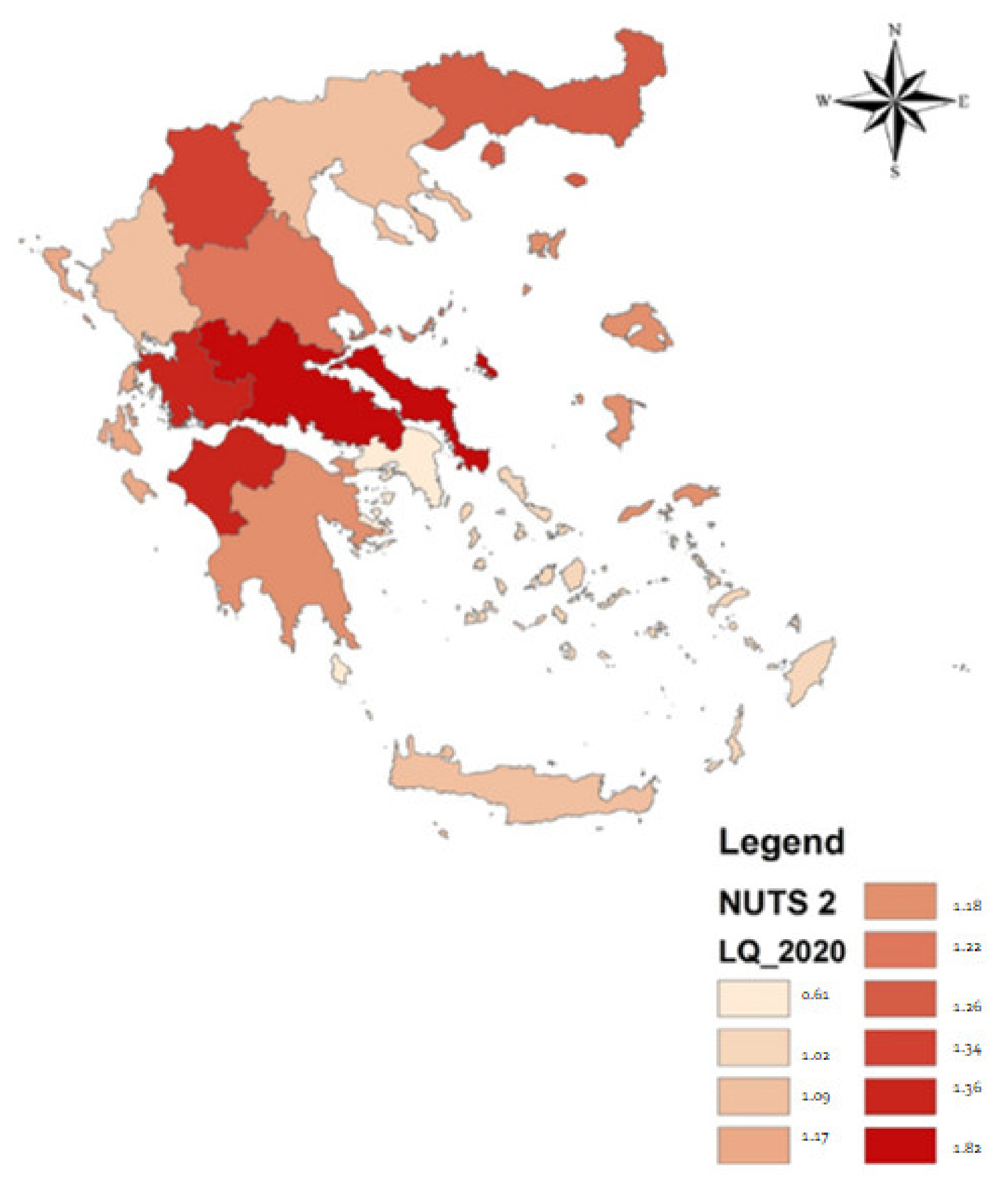

2.1. Unemployment: The Most Important Challenge Faced by Youth in the Labor Market in Times of Crisis

2.2. Entrepreneurship as a Youth Response to the Effects of a Crisis

2.3. Driving Factors of Youth’s Entrepreneurial Intention

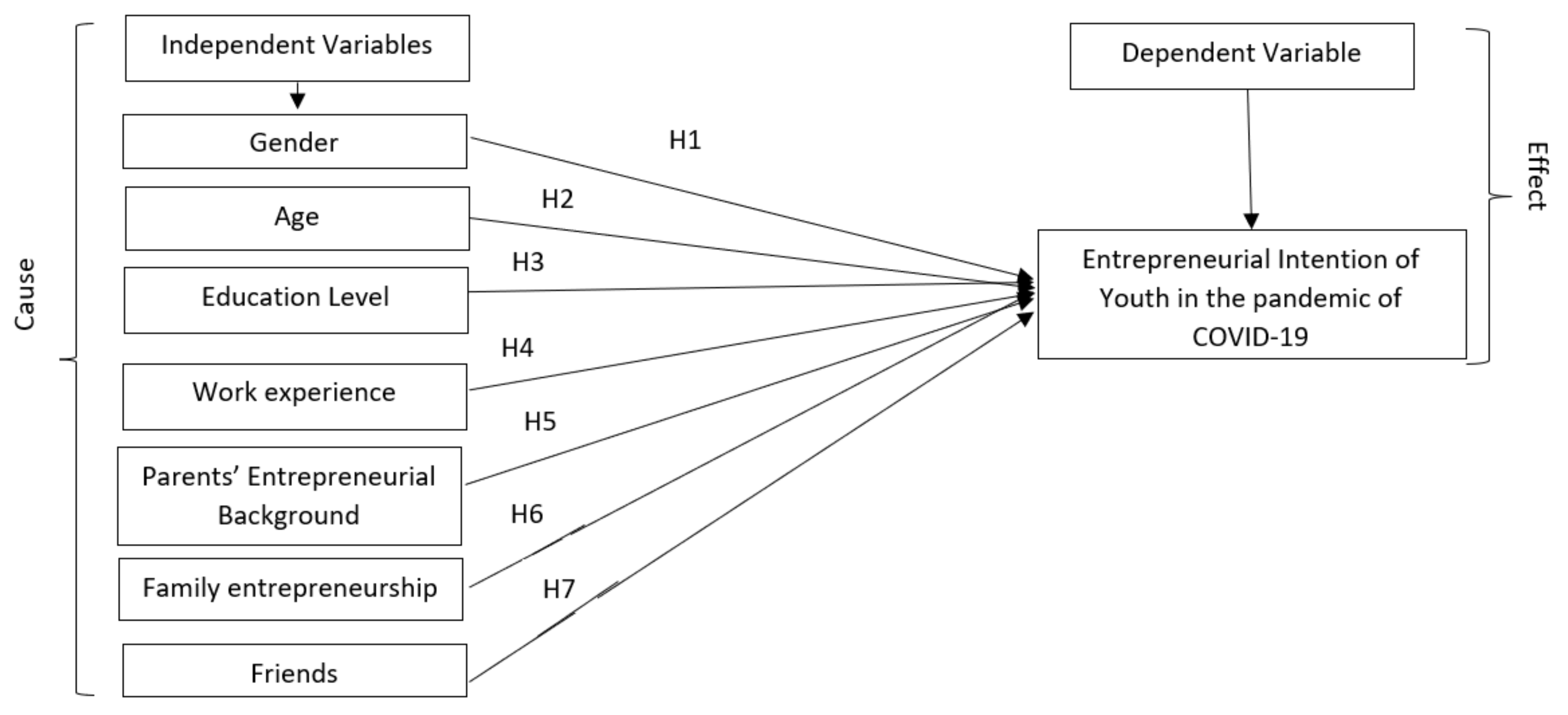

3. Materials and Methods

Data and Method

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model | Model Fitting Criteria | Likelihood Ratio Tests | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2 Log Likelihood | Chi-Square | df | Sig. | |

| Intercept only | 496,753 | |||

| Final | 331,139 | 165,614 | 56 | 0.000 |

Appendix B

| Cox and Snell | 0.362 |

| Nagelkerke | 0.489 |

| McFadden | 0.333 |

References

- Kourilsky, M.L.; Walstad, W.B. Entrepreneurship and female youth: Knowledge, attitudes, gender differences, and educational practices. J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, M.; Cifuentes-Faura, J. Can unemployment forecasts based on Google Trends help government design better policies? An investigation based on Spain and Portugal. J. Policy Modeling 2021, 44, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetreault, E.; Teferra, A.A.; Keller-Hamilton, B.; Shaw, S.; Kahassai, S.; Curran, H.; Paskett, E.D.; Ferketich, A.K. Perceived Changes in Mood and Anxiety Among Male Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings From a Mixed-Methods Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Ozbilgin, M. Age, industry, and unemployment risk during a pandemic lockdown. J. Econ. Dyn. Control. 2021, 133, 104233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruchowicz, C.; Parker, S.W.; Robbins, L. Time use of youth during a pandemic: Evidence from Mexico. World Dev. 2022, 149, 105687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannister, M.W. Youth Ministry Pioneers of the 20Th Century: Part III. Christ. Educ. J. Res. Educ. Minist. 2004, 1, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotti, G. Labour market flexibility, economic crisis and youth unemployment in Italy. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2020, 54, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompei, F.; Selezneva, E. Unemployment and education mismatch in the EU before and after the financial crisis. J. Policy Modeling 2021, 43, 448–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, N.; Amanaki, E.; Drakaki, M.; Saridaki, S. Employment/unemployment, education and poverty in the Greek Youth, within the EU context. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 99, 101503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.N.; Blanchflower, D.G. Youth unemployment in Greece: Measuring the challenge. IZA J. Eur. Labor Stud. 2015, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, S.B.; Johnson, E.B. The location quotient as an estimator of industrial concentration. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2012, 42, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, M.N. Measuring size distortions of location quotients. Int. Econ. 2021, 167, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, G.; Kaliampakos, D. Location quotient-based travel costs for determining accessibility changes. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 91, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshray, A.; Ordóñez, J.; Sala, H. Euro, crisis and unemployment: Youth patterns, youth policies? Econ. Model. 2016, 58, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nasar, A.; Akram, M.; Safdar, M.R.; Akbar, M.S. A qualitative assessment of entrepreneurship amidst COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2021, 27, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Lehmann, E.E.; Menter, M.; Wirsching, K. Intrapreneurship and absorptive capacities: The dynamic effect of labor mobility. Technovation 2021, 99, 102129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, R.S.R.; Zulkharnain, A.; Hashim, Z.; Ibrahim, W.N.W.; Yusof, S.E. Regenerating Youth Development through Entrepreneurship. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 129, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ran, L.; Tan, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y. The application of subjective and objective method in the evaluation of healthy cities: A case study in Central China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervelló-Royo, R.; Moya-Clemente, I.; Perelló-Marín, M.R.; Ribes-Giner, G. Sustainable development, economic and financial factors, that influence the opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. An fsQCA approach. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Nazari, M.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, N. Opportunity-based entrepreneurship and environmental quality of sustainable development: A resource and institutional perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udimal, T.B.; Luo, M.; Liu, E.; Mensah, N.O. How has formal institutions influenced opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship? The case of brics economies. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y. Regional governments and opportunity entrepreneurship in underdeveloped institutional environments: An entrepreneurial ecosystem perspective. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olugbola, S.A. Exploring entrepreneurial readiness of youth and startup success components: Entrepreneurship training as a moderator. J. Innov. Knowl. 2017, 2, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.; Perez, J.P.; Novoa, S. Developing orientation to achieve entrepreneurial intention: A pretest-post-test analysis of entrepreneurship education programs. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, R.S.; King, K.A. Does school choice increase the rate of youth entrepreneurship? Econ. Educ. Rev. 2008, 27, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chan, R.C.K. Gendered digital entrepreneurship in gendered coworking spaces: Evidence from Shenzhen, China. Cities 2021, 119, 103411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatak, I.; Harms, R.; Fink, M. Age, job identification, and entrepreneurial intention. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turker, D.; Selcuk, S.S. Which factors affect entrepreneurial intention of university students? J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2009, 33, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, W.G.W. Family education? Unpacking parental factors for tourism and hospitality students’ entrepreneurial intention. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorgren, S.; Sirén, C.; Nordström, C.; Wincent, J. Hybrid entrepreneurs’ second-step choice: The nonlinear relationship between age and intention to enter full-time entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2016, 5, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, S.; Rachwał, T. Development of entrepreneurship in ageing populations of The European Union. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 19, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Mundorf, N.; Salzarulo-McGuigan, A. Entrepreneurship education enhances entrepreneurial creativity: The mediating role of entrepreneurial inspiration. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 20, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyver, K.; Steffens, P.; Lomberg, C. Having your cake and eating it too? A two-stage model of the impact of employment and parallel job search on hybrid nascent entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 106042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, F.; Giones, F.; Riverola, C. Evaluating the impact of prior experience in entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choukir, J.; Aloulou, W.J.; Ayadi, F.; Mseddi, S. Influences of role models and gender on Saudi Arabian freshman students’ entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2019, 11, 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laviolette, E.M.; Lefebvre, M.R.; Brunel, O. The impact of story bound entrepreneurial role models on self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2012, 18, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osanya, J.; Adam, R.I.; Otieno, D.J.; Nyikal, R.; Jaleta, M. An analysis of the respective contributions of husband and wife in farming households in Kenya to decisions regarding the use of income: A multinomial logit approach. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2020, 83, 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhamtyrova, R.; Kalnishkan, Y. Universal algorithms for multinomial logistic regression under Kullback–Leibler game. Neurocomputing 2020, 397, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, S.; Obschonka, M.; Audretsch, D.B. Entrepreneurship in Cities. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.H.; Kim, Y.H. An improved forecast of precipitation type using correlation-based feature selection and multinomial logistic regression. Atmos. Res. 2020, 240, 104928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridakis, G.; Georgellis, Y.; Muñoz Torres, R.I.; Mohammed, A.M.; Blackburn, R. From subsistence farming to agribusiness and nonfarm entrepreneurship: Does it improve economic conditions and well-being? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedeker, D. A mixed-effects multinomial logistic regression model. Stat. Med. 2003, 22, 1433–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkweather, J.; Moske, A. Multinomial Logistic Regression. 2011. Available online: https://it.unt.edu/sites/default/files/mlr_jds_aug2011.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Schnell, T.; Gerstner, R.; Krampe, H. Crisis of meaning predicts suicidality in youth independently of depression. Crisis 2018, 39, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.L.; Shewark, E.A.; Hyde, L.W.; Klump, K.L.; Burt, S.A. Understanding the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Youth Psychopathology: Genotype–Environment Interplay. Biol. Psychiatry Glob. Open Sci. 2021, 1, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C.H.; Berry, I.; Okumu, M.; Loutet, M.; McNamee, C.; Hakiza, R.; Musoke, D.K.; Mwima, S.; Kyambadde, P.; Mbuagbaw, L. The prevalence and correlates of depression before and after the COVID-19 pandemic declaration among urban refugee adolescents and youth in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda: A longitudinal cohort study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2022, 66, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, L. The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Risk of Youth Substance Use. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 467–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamrawy, R.G.; Fadl, N.; Khaled, A. Psychiatric morbidity and dietary habits during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study among Egyptian Youth (14–24 years). Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2021, 28, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakka, S.; Aliki Nikopoulou, V.; Bonti, E.; Tatsiopoulou, P.; Karamouzi, P.; Aliki, V. Assessing test anxiety and resilience among Greek adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Mind Med Sci. 2020, 7, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leschke, J.; Weiss, S. With a Little Help from My Friends: Social-Network Job Search and Overqualification among Recent Intra-EU Migrants Moving from East to West. Work. Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 769–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raybould, M.; Wilkins, H. Over qualified and under experienced: Turning graduates into hospitality managers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, S.P.; Jagannathan, M.; Pritchard, A.C. Too Busy to Mind the Business? Monitoring by Directors with Multiple Board Appointments. J. Financ. 2003, 58, 1087–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Navarro, P. The MBA core curricula of top-ranked U.S. business schools: A study in failure? Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2008, 7, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J.; Tickell, A. Business Goes Local: Dissecting the “Business Agenda” in Manchester. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1995, 19, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, S.; Abidin, N.; Sapuan, N.M.; Rajadurai, J. Enhancing university business curriculum using an importance-performance approach: A case study of the business management faculty of a university in Malaysia. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2011, 25, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorks, L.; Beechler, S.; Ciporen, R. Enhancing the impact of an open-enrollment executive program through assessment. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2007, 6, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimunović, M.; Babarović, T. The role of parents’ beliefs in students’ motivation, achievement, and choices in the STEM domain: A review and directions for future research. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 23, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Shin, D.D.; Bong, M. Boys are Affected by Their Parents More Than Girls are: Parents’ Utility Value Socialization in Science. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verd, J.M.; Barranco, O.; Bolíbar, M. Youth unemployment and employment trajectories in Spain during the Great Recession: What are the determinants? J. Labour Mark. Res. 2019, 53, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phillips, S.; Sandstrom, K.L. Parental attitudes toward youth work. Youth Soc. 1990, 22, 160–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, F.; Giones, F.; Gozun, B. Does direct experience matter? Examining the consequences of current entrepreneurial behavior on entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 881–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, S.; Bundick, M.J.; Malin, H.; Reilly, T.S. How Supportive of Their Specific Purposes Do Youth Believe Their Family and Friends Are? J. Adolesc. Res. 2012, 28, 348–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Almerigi, J.B.; Theokas, C.; Phelps, E.; Gestsdottir, S.; Naudeau, S.; Jelicic, H.; Alberts, A.; Ma, L.; et al. Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. J. Early Adolesc. 2005, 25, 17–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questions | Variables | Alternatives | Ν | % | Mean | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is your sex? | Sex | Male | 137 | 37.1 | |||

| Female | 232 | 62.9 | |||||

| How old are you? | Age, mean (std. dev.) | 23.5 (7.72) | 23.5 | 18 | 55 | ||

| What is your educational level? | Education level | Undergraduate | 337 | 91.3 | |||

| Postgraduate | 32 | 8.7 | |||||

| Do you have any work experience? | Work experience | No | 119 | 32.2 | |||

| Yes | 250 | 67.8 | |||||

| How many years of work experience do you have? | Years of work experience | None | 119 | 32.2 | |||

| Less than 1 year | 90 | 24.4 | |||||

| 1–3 years | 62 | 16.8 | |||||

| More than 3 years | 98 | 26.6 | |||||

| Do you have work experience in a family business? | Experience in family business | None | 158 | 63.2 | |||

| Less than 1 year | 32 | 12.8 | |||||

| 1–3 years | 23 | 9.2 | |||||

| More than 3 years | 37 | 14.8 | |||||

| Please indicate your father’s work status | Father’s work status | Entrepreneur | 64 | 17.4 | |||

| In private sector | 134 | 36.3 | |||||

| In public sector | 109 | 29.5 | |||||

| Other | 62 | 16.8 | |||||

| Please indicate your mother’s work status | Mother’s work status | Entrepreneur | 24 | 6.4 | |||

| In private sector | 123 | 33.3 | |||||

| In public sector | 96 | 26 | |||||

| Other | 126 | 34.1 |

| Questions | Variable | Alternatives | Ν | % | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you plan to start a business within the next year? | Youth’s willingness | Not at all likely | 289 | 78.3 | 1.33 | 0.66 | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate likely | 40 | 10.8 | ||||||

| Very likely | 40 | 10.8 | ||||||

| Please indicate the degree to which you believe best represents your level of business knowledge | Knowledge | Not at all knowledge | 145 | 39.3 | 1.92 | 0.84 | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate knowledge | 109 | 29.5 | ||||||

| Very high knowledge | 115 | 31.2 | ||||||

| How attractive is it for you to combine part-time employment with entrepreneurship? | Mixed work status | Not at all attractive | 82 | 22.2 | 2.33 | 0.82 | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate attractive | 83 | 22.5 | ||||||

| Very attractive | 204 | 55.3 | ||||||

| How attractive is entrepreneurship to you? | Attractiveness of being entrepreneur | Not at all attractive | 99 | 26.8 | 2.24 | 0.85 | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate attractive | 82 | 22.2 | ||||||

| Very attractive | 188 | 50.9 | ||||||

| Does being an entrepreneur mean great satisfaction for you? | Satisfaction | Not at all | 76 | 20.6 | 2.34 | 0.8 | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate | 92 | 24.9 | ||||||

| Very much | 201 | 54.5 | ||||||

| Are you ready to make every effort to become an entrepreneur? | Efforts toward entrepreneurship | Not at all | 179 | 48.5 | 1.81 | 0.86 | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate | 82 | 22.2 | ||||||

| Very much | 108 | 29.3 | ||||||

| Please indicate the degree to which your friends would support your decision to start a business | Friends’ support | Not at all | 29 | 7.9 | 2.7 | 0.61 | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate | 51 | 13.8 | ||||||

| Very much | 289 | 78.3 | ||||||

| Do you feel you have the ideas to establish a new business? | Creative ideas | Not at all | 153 | 41.5 | 2.07 | 0.95 | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate | 37 | 10.0 | ||||||

| Very much | 179 | 48.5 | ||||||

| Do you believe that it is difficult to develop a business plan in Greece during the COVID-19 pandemic? | Difficulties in business plan | Not at all | 68 | 18.4 | 2.35 | 0.77 | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate | 104 | 28.2 | ||||||

| Very much | 197 | 53.4 |

| 2 vs. 1 | OR | Std. Error | p | 95% Δ.Ε. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.388 | 0.457 | 0.039 | 0.158–0.952 |

| Female | ||||

| Father’s work status | ||||

| Entrepreneur | 1.765 | 0.783 | 0.468 | 0.381–8.186 |

| In private sector | 3.275 | 0.640 | 0.064 | 0.935–11.474 |

| In public sector | 1.047 | 0.721 | 0.950 | 0.255–4.3 |

| Other | ||||

| Mother’s work status | ||||

| Entrepreneur | 0.139 | 1.188 | 0.097 | 0.014–1.426 |

| In private sector | 0.832 | 0.486 | 0.704 | 0.321–2.154 |

| In public sector | 0.538 | 0.588 | 0.291 | 0.17–1.702 |

| Other | ||||

| Education level | ||||

| Undergraduate | 1.292 | 0.954 | 0.789 | 0.199–8.385 |

| Post graduate | ||||

| Work experience | ||||

| No | 2.775 | 0.811 | 0.208 | 0.566–13.601 |

| Yes | ||||

| Years of work experience | ||||

| None | 0.329 | 0.857 | 0.195 | 0.061–1.767 |

| Less than 1 year | 1.500 | 0.795 | 0.610 | 0.316–7.125 |

| 1–3 years | ||||

| More than 3 years | ||||

| Experience in family business | ||||

| None | 0.489 | 0.850 | 0.400 | 0.093–2.588 |

| Less than 1 year | 0.093 | 1.204 | 0.048 | 0.009–0.98 |

| 1–3 years | 1.172 | 0.853 | 0.853 | 0.22–6.24 |

| More than 3 years | ||||

| Age | 0.967 | 0.046 | 0.468 | 0.883–1.059 |

| Knowledge | 1.096 | 0.266 | 0.731 | 0.651–1.844 |

| Moderate knowledge | 1.174 | 0.249 | 0.519 | 0.721–1.913 |

| Mixed work status | 2.292 | 0.325 | 0.011 | 1.213–4.33 |

| Attractiveness of being an entrepreneur | 2.094 | 0.341 | 0.030 | 1.074–4.082 |

| Satisfaction | 0.968 | 0.311 | 0.916 | 0.526–1.778 |

| Efforts toward entrepreneurship | 0.614 | 0.294 | 0.098 | 0.345–1.094 |

| Friends’ support | 1.594 | 0.398 | 0.241 | 0.731–3.477 |

| Lack of creative ideas | 1.633 | 0.222 | 0.027 | 1.056–2.525 |

| Difficulties with business plan | 0.603 | 0.265 | 0.056 | 0.359–1.013 |

| 3 vs 1 | OR | Std. Error | p | 95% Δ.Ε. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.391 | 0.469 | 0.482 | 0.554, 3.491 |

| Female | ||||

| Father’s work status | ||||

| Entrepreneur | 3.440 | 0.813 | 0.129 | 0.699, 16.932 |

| In private sector | 4.657 | 0.767 | 0.045 | 1.036, 20.942 |

| In public sector | 2.254 | 0.712 | 0.254 | 0.558, 9.098 |

| Other | ||||

| Mother’s work status | ||||

| Entrepreneur | 0.715 | 0.915 | 0.714 | 0.119, 4.295 |

| In private sector | 0.455 | 0.617 | 0.202 | 0.136, 1.526 |

| In public sector | 0.249 | 0.680 | 0.041 | 0.066, 0.945 |

| Other | ||||

| Education level | ||||

| Undergraduate | 0.182 | 0.882 | 0.054 | 0.032, 1.026 |

| Post graduate | ||||

| Work experience | ||||

| No | 4.546 | 0.890 | 0.089 | 0.794, 26.021 |

| Yes | ||||

| Years of work experience | ||||

| None | 0.991 | 0.862 | 0.992 | 0.183, 5.373 |

| Less than 1 year | 0.748 | 0.841 | 0.730 | 0.144, 3.888 |

| 1–3 years | ||||

| More than 3 years | ||||

| Experience in family business | ||||

| None | 0.749 | 0.922 | 0.754 | 0.123, 4.569 |

| Less than 1 year | 0.079 | 1.265 | 0.045 | 0.007, 0.943 |

| 1–3 years | 0.358 | 0.860 | 0.232 | 0.066, 1.932 |

| More than 3 years | ||||

| Age | 1.021 | 0.040 | 0.595 | 0.945, 1.104 |

| Knowledge | 1.005 | 0.319 | 0.987 | 0.538, 1.878 |

| Moderate knowledge | 1.686 | 0.289 | 0.071 | 0.956, 2.971 |

| Mixed work status | 0.625 | 0.329 | 0.153 | 0.328, 1.19 |

| Attractiveness of being entrepreneur | 0.445 | 0.428 | 0.058 | 0.193, 1.029 |

| Satisfaction | 13.807 | 0.900 | 0.004 | 2.365, 80.597 |

| Efforts toward entrepreneurship | 3.955 | 0.396 | 0.001 | 1.82, 8.592 |

| Friends’ support | 12.057 | 1.028 | 0.015 | 1.607, 90.464 |

| Lack of creative ideas | 0.823 | 0.260 | 0.453 | 0.494, 1.37 |

| Difficulties with business plan | 0.809 | 0.306 | 0.487 | 0.444, 1.472 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ragazou, K.; Passas, I.; Garefalakis, A.; Kourgiantakis, M.; Xanthos, G. Youth’s Entrepreneurial Intention: A Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis of the Factors Influencing Greek HEI Students in Time of Crisis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013164

Ragazou K, Passas I, Garefalakis A, Kourgiantakis M, Xanthos G. Youth’s Entrepreneurial Intention: A Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis of the Factors Influencing Greek HEI Students in Time of Crisis. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013164

Chicago/Turabian StyleRagazou, Konstantina, Ioannis Passas, Alexandros Garefalakis, Markos Kourgiantakis, and George Xanthos. 2022. "Youth’s Entrepreneurial Intention: A Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis of the Factors Influencing Greek HEI Students in Time of Crisis" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013164