Authenticity Mediates the Relationship between Risk Perception of COVID-19 and Subjective Well-Being: A Daily Diary Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. RPC and SWB

1.2. The Mediating Role of Authenticity

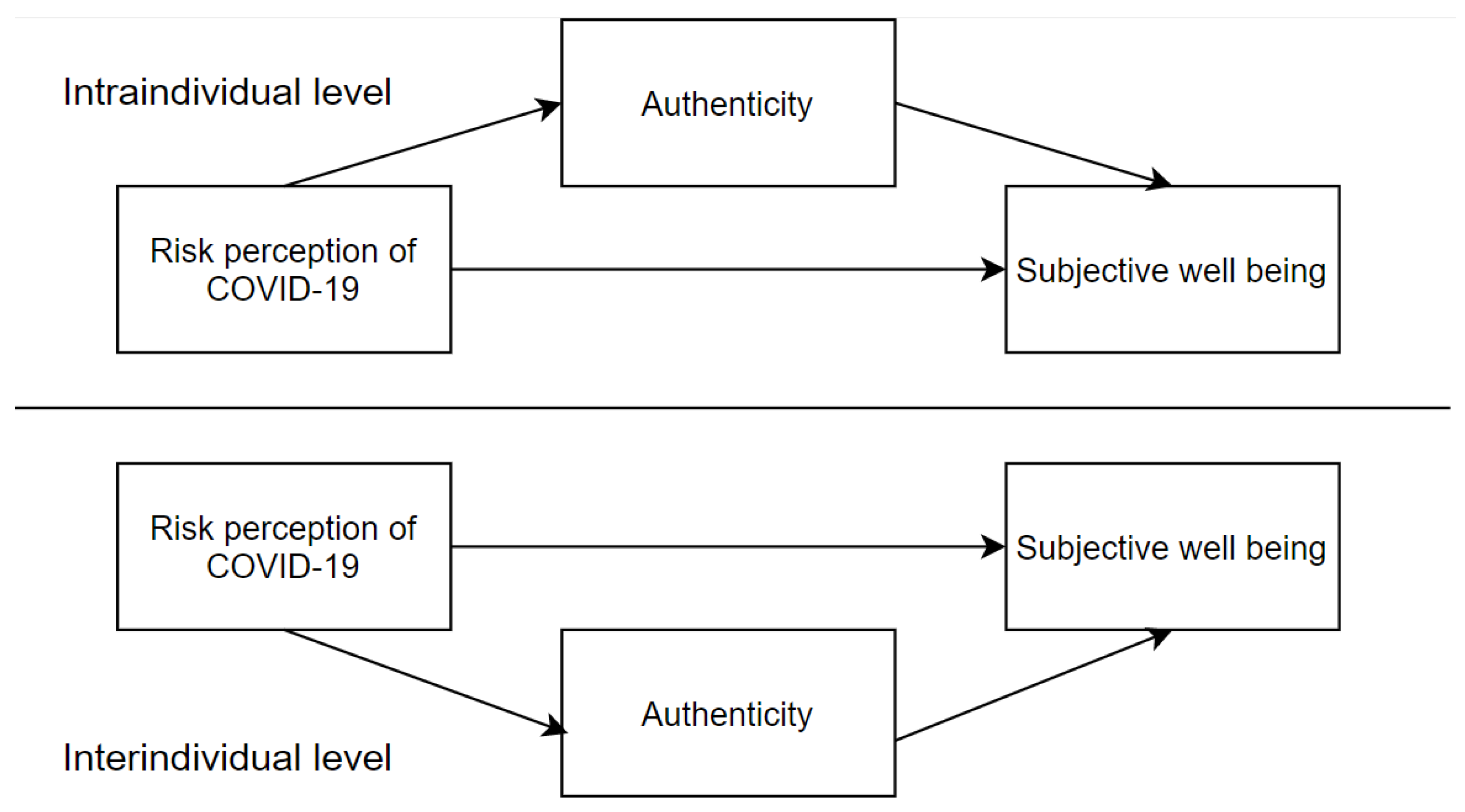

1.3. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurement

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Harman’s Single Factor Test, Results of Intraclass-Coefficients (ICCs) and Correlations

3.2. The Effect of RPC and Authenticity on SWB

3.3. The Mediating Effect of Authenticity

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationship between RPC and SWB

4.2. Relationship between RPC and Authenticity

4.3. Relationship between Authenticity and SWB

4.4. The Mediation Effect of Authenticity

4.5. Implications

5. Limitations and Future Direction

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tejamaya, M.; Widanarko, B.; Erwandi, D.; Putri, A.A.; Sunarno, S.D.A.M.; Wirawan, I.M.A.; Kurniawan, B.; Thamrin, Y. Risk perception of COVID-19 in Indonesia during the first stage of the pandemic. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 731459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollè, L.; Trombetta, T.; Calabrese, C.; Vismara, L. Adult attachment, loneliness, COVID-19 risk perception and perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zheng, B.; Agostini, M.; Belanger, J.J.; Gutzkow, B.; Kreienkamp, J.; Reitsema, A.M.; van Breen, J.A.; Leander, N.P. Associations of risk perception of COVID-19 with emotion and mental health during the pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 284, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, D.; Zarzycka, B.; Telka, E. Risk perception of Covid-19, religiosity, and subjective well-being in emerging adults: The mediating role of meaning-making and perceived stress. J. Psychol. Theol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, D.; Zarzycka, B. Risk perception of COVID-19, meaning-based resources, and psychological well-being amongst healthcare personnel: The mediating role of coping. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.J.; Medaglia, J.D.; Jeronimus, B.F. Lack of group-to individual generalizability is a threat to human subjects research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E6106–E6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, I.A.; Bhatti, S.S.; Aslam, A.B.; Jamshed, A.; Ahmad, J.; Shah, A.A. COVID-19 risk perception and coping mechanisms: Does gender make a difference? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 55, 102096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caroline, R. How do we handle new health risks? Risk perception, optimism, and behaviors regarding the H1N1 virus. J. Risk Res. 2013, 16, 959–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Siegrist, M. How a nuclear power plant accident influences acceptance of nuclear power: Results of a longitudinal study before and after the Fukushima disaster. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebayashi, Y.; Lyamzina, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Murakami, M. Risk perception and anxiety regarding radiation after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear power plant accident: A systematic qualitative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.B.; Xu, J.L.; Huang, S.S.; Li, P.P.; Lu, C.Z.; Xie, S.H. Risk perception and depression in public health crises: Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Feng, X.N.; Li, Y.W.; Chen, X.H.; Jia, J.M. Environmental risk perception and its influence on well-being. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2017, 11, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, R. Psychological drivers of individual differences in risk perception: A systematic case study focusing on 5G. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 32, 1592–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, U.; Krause, P.; Wagner, G.G.; Schupp, J. Stability and change of well-being: An experimentally enhanced latent state-trait-error analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 95, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, A.; Garling, T. The relationships between subject well-being, happiness, and current mood. J. Happiness Stud. 2012, 13, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J.; Baliousis, M.; Joseph, S. The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization, and the development of the Authenticity Scale. J. Couns. Psychol. 2008, 55, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, R.J.; Hicks, J.A. The true self and psychological health: Emerging evidence and future directions. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass. 2011, 5, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rever; George, W. Attachment and Loss. Vol. 1. Attachment. Psychosom. Med. 1972, 34, 562–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Sadness and Depression in Attachment and Loss; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, W.S.; Ryan, R.M. Toward a Social Psychology of Authenticity: Exploring Within-Person Variation in Autonomy, Congruence, and Genuineness Using Self-Determination Theory. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2019, 23, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, D.E.; Lehinger, E.; Cobos, B.; Vail, K.E.; Mcgeary, D.D. Authenticity as a resilience factor against cv-19 threat among those with chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 643869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, J.; Dik, B.J.; You, X. Reciprocal relation between authenticity and career decision self-efficacy: A longitudinal study. J. Career Dev. 2021, 48, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenton, A.P.; Bruder, M.; Slabu, L.; Sedikides, C. How does “being real” feel? The experience of state authenticity. J. Pers. 2013, 81, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenton, A.P.; Slabu, L.; Sedikides, C. State authenticity in everyday life. Eur. J. Pers. 2016, 30, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, R.; Taris, T. Authenticity at work: Its relations with worker motivation and well-being. Front. Commun. 2018, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, U.B.; Taris, T.W.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Van Beek, I.; Van den Bosch, R. Authenticity at work: A job-demands resources perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.A.; Cassidy, J. Empathy from infancy to adolescence: An attachment perspective on the development of individual differences. Dev. Rev. 2018, 47, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabu, L.; Lenton, A.P.; Sedikides, C.; Bruder, M. Trait and state authenticity across cultures. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 1347–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Authenticity in context: Being true to working selves. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2019, 23, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Keller, C.; Kiers, H.A.L. A new look at the psychometric paradigm of perception of hazards. Risk Anal. 2005, 25, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, C.W.; Peek, L.; Meyer, M.A.; Marlatt, H.L.; Gruntfest, E.; McNoldy, B.D.; Schubert, W.H. A cognitive-affective scale for hurricane risk perception. Risk Anal. 2016, 36, 2233–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaes, S.; Sedikides, C.; Nellie, V.D.B.; Hutteman, R.; Reijntjes, A. Happy to be “me?” authenticity, psychological need satisfaction, and SWB in adolescence. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemsen, E.; Roth, A.; Oliveira, P. Common Method Bias in Regression Models with Linear, Quadratic, and Interaction Effects. Organ. Res. Methods. 2010, 13, 456–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the modeling of the contingencies of mechanisms. Am. Behav. Sci. 2020, 64, 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P.D. An introduction to multilevel modeling techniques. Pers. Psychol. 2000, 53, 1062–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Schudy, A.; Zurek, K.; Wi’sniewska, M.; Piejka, A.; Gaweda, Ł.; Okruszek, Ł. Mental well-being during pandemic: The role of cognitive biases and emotion regulation strategies in risk perception and affective response to COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 589973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Ryan, R.M.; Rawsthorne, L.J.; Ilardi, B. Trait self and true self: Cross-role variation in the Big-Five personality traits and its relations with psychological authenticity and subjective well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 1380–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnera, A.; Zarbo, C.; Compare, A.; Talia, A.; Tasca, G.A.; Greco, A.; Greco, F.; Pievani, L.; Auteri, A. Self-reported reflective functioning mediates the association between attachment insecurity and well-being among psychotherapists. Psychother. Res. 2020, 31, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidman, G. Expressing the ‘‘true self’’ on Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillath, O.; Sesko, A.K.; Shaver, P.R.; Chun, D.S. Attachment, authenticity, and honesty: Dispositional and experimentally induced security can reduce self- and other-deception. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, F.G.; Rice, K.G.; Duran, B.S.; Hong, J. Profiling authentic self-development: Associations with basic need satisfaction in emerging adulthood. Emerg. Adulthood. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillow, D.R.; Hale, W.J.; Crabtree, M.A.; Hinojosa, T.L. Exploring the relations between self-monitoring, authenticity, and well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, Z.F.; Hao, M.Y.; Zhu, X.L.; Wang, F. Objectification limits authenticity: Exploring the relations between objectification, perceived authenticity, and subjective well-being. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 61, 622–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasco, D.; Warner, R.M. Relationship authenticity partially mediates the effects of attachment on relationship satisfaction. J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 157, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, D.A.; Zautra, A. The trait-state-error model for multiwave data. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1995, 63, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Risk perception of COVID-19 | −0.26 ** | −0.23 ** | ||

| 2 Authenticity | −0.30 ** | 0.40 ** | ||

| 3 Subjective well-being | −0.24 ** | 0.43 ** | ||

| 4 Age | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.25 ** |

| Path | B | SE | t | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | ||||

| Risk perception of COVID-19 → Authenticity | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.06 | [−0.07, 0.08] |

| Authenticity → Subjective well-being | 1.68 | 0.14 | 11.75 ** | [1.40, 1.96] |

| Risk perception of the COVID-19 → Subjective well-being | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.24 | [−0.36, 0.47] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Risk perception of COVID-19 → Authenticity | −0.28 | 0.07 | −3.67 ** | [−0.42, −0.13] |

| Gender → Authenticity | −0.23 | 0.264 | −0.88 | [−0.67, 0.20] |

| Age → Authenticity | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.28 | [−0.14, 0.11] |

| Authenticity → Subjective well-being | 1.98 | 0.42 | 4.81 ** | [1.16, 2.79] |

| Risk perception of the COVID-19→ Subjective well-being | −0.98 | 0.36 | −2.78 ** | [−1.68, −0.27] |

| Gender → Subjective well-being | −0.81 | 1.41 | −0.57 | [−3.58, 1.96] |

| Age → Subjective well-being | 0.94 | 0.30 | 3.13 | [0.35, 1.52] |

| B1 * B2 | SE | z | 95% MC CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | ||||

| Risk perception of COVID-19 → Authenticity → Subjective well-being | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.06 | [−0.13, 0.14] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Risk perception of COVID-19 → Authenticity → Subjective well-being | −0.54 | 0.26 | −2.16 * | [−0.97, −0.23] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, S. Authenticity Mediates the Relationship between Risk Perception of COVID-19 and Subjective Well-Being: A Daily Diary Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013304

Xu X, Fan Y, Wu Y, Zhou S. Authenticity Mediates the Relationship between Risk Perception of COVID-19 and Subjective Well-Being: A Daily Diary Study. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013304

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xizheng, Ying Fan, Yunpeng Wu, and Senlin Zhou. 2022. "Authenticity Mediates the Relationship between Risk Perception of COVID-19 and Subjective Well-Being: A Daily Diary Study" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013304

APA StyleXu, X., Fan, Y., Wu, Y., & Zhou, S. (2022). Authenticity Mediates the Relationship between Risk Perception of COVID-19 and Subjective Well-Being: A Daily Diary Study. Sustainability, 14(20), 13304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013304