This section provides a theoretical overview of the theories, concepts, and variables used in this study. The aim is to develop a theoretical model and hypothesis.

The literature has focused on the impact of strategic planning and business innovation on sustainable performance in large enterprises. However, the SMEs’ perspective is significantly neglected, especially in developing countries. SMEs are a crucial pillar to the success of the development cycle of economies in industrialized, emerging, and developing nations as they are considered the significant primary source of employment generation [

7,

28]. Nevertheless, governments in developing countries are significantly dependent on the efficiency of SMEs to absorb jobs compared to established economies, which are heavily reliant on the success of large domestic and international firms [

7,

29,

30,

31]. In the meantime, a country’s overall economic health may suffer if SMEs do not have enough clear strategies, financial, and non-financial resources, such as adequate human capital and affordable raw material and energy. For this reason, authorities and other support organizations should provide all the necessary assistance to SMEs, such as policy support and business-enabling environmental regulations and actions [

8,

32,

33].

Although SMEs contribute considerably to economic growth worldwide, they face a challenge concerning material scarcity as they contribute to global raw material consumption, which will quadruplicate by 2060 due to the development of the global economy and the rise in the average quality of life [

34]. Therefore, SMEs must successfully adapt their operations to the sustainability model since different organizations frequently face sustainable development challenges [

35]. They should be prepared to encounter the expected scarcity in raw materials by enhancing their resource efficiency, energy efficiency, and production techniques [

36]. In parallel, industrial firms must consider complying with strict environmental requirements and rising societal pressure due to deteriorating climatic circumstances [

37]. Thus, all kinds of enterprises, mainly SMEs, are recommended to adopt new business models with resilient and innovative business strategies through which they can attain sustainability [

7,

8,

9].

In Arab countries, SMEs lead to economic development through creating sources of employment and promoting innovation [

8]. Yet, SMEs in developing economies encounter managerial issues that limit their growth, lower their aimed performances, and threaten their sustainably. These challenges can be summarized as follows: first, difficulties in long-term planning; second, the absence of vision and strategic orientation; third, a lack of planning skills; fourth, the absence of creative and innovative solutions to keep pace with the dynamic changes in business surroundings; fifth, not being sufficiently resilient to be able to react to dynamic environments, sixth, high operation costs; and seventh, a weak ability to articulate a given challenge, and an inability to define constraints [

19,

38,

39,

40]. Additionally, SMEs’ top management in developing countries lacks business-related skills [

40,

41].

2.1. Triple Bottom Line (TBL) and Resources Based View (RBV)Theories

The underpinning theories used for the research model in this study are the triple bottom line (TBL) and resource-based view (RBV) theories. Sustainability and the triple bottom line (TBL) are two closely related concepts frequently and equally used in the literature [

47,

48]. Furthermore, the TBL establishes a framework for evaluating business entities’ performance and achievement via three balanced dimensions: economic, social, and environmental [

49]. Consequently, the term TBL has been used to refer to the operational basis for sustainability [

50]. Back in the early 1990s, the phrase TBL was unknown. TBL terminology was invented in the 1990s by John Elkington, a business development advisor; “TBL introduced the economic, environmental, and social value of the asset that may accumulate outside a firm’s financial bottom line”. Elkington defined the TBL using profit, people, and the planet as the line segments [

51].

Regarding balance, the TBL assigns equal weight to each of the three lines; this results in the construct being more balanced and coherent [

51,

52,

53]. The TBL methodology uses the value properties more precisely and uses the available tangible and intangible resources most sufficiently. Hence, firms’ assets must be utilized competently and efficiently [

50,

54]. Therefore, firms are gradually evaluated according to their stakeholders’ environmental impacts and critical economic and social performance results. Sustainable performance implies that companies can achieve preferred public, environmental, and economic results, called “People, Planet, and profit 3Ps”, the three-layered, value-adding, and combined value [

55]. As a result of the TBL, sustainability management includes several proportions equally: environmental, social, and economical.

On the one hand, the perception of companies’ performance and strategic management is initiated and derived from various underpinning theories such as the Resource-Based View (RBV) [

56]. In this regard, Barney (1991) emphasized that each company has its own unique intangible and physical assets, which are different from others in terms of their capabilities, competitive advantages, skills, competencies, experience, systems, procedures, and information systems. Therefore, to sustain a business firm, its competitive advantages and capabilities become the RBV’s main priority [

57]. Subsequently, a firm that complies with quality, uniqueness, inimitableness, and non-substitutability can achieve long-term competitiveness [

57]. Moreover, The Resource-Based View RBV theory emphasizes the company’s physical and intangible resources and the employees’ competencies, stating the uniqueness of these assets, which empowers companies to attain sustainable performance [

58]. Similarly, a review paper studying the application of RBV theory to a firm in an empirical work highlighted that the RBV has been profusely examined and studied as a way to describe the conditions under which a company can gain a long-term competitive edge [

59].

Through the triple bottom line (TBL) and Resource-based view (RBV) theories, businesses, mainly SMEs, can better understand how to maintain a sustainable business performance and develop a competitive edge in an unstable environment by fully utilizing their capabilities and available resources efficiently. As a result, the TBT and RBV theories were applied in this research study to evaluate the sustainable performance of manufacturing SMEs in Palestine by assessing their environmental, economic, and social performances.

2.2. Sustainable Performance

The recent economic and social development trends have increased the consumption of goods dramatically, resulting in the depletion of natural assets and possibly even endangering the continued good health of human communities [

55,

60,

61]. In this regard, the evaluation of the performance of companies and businesses is being expanded and shifted to consider social and environmental aspects along with financial results [

58]. Most business owners, CEOs, and specialists have recently measured firm performance by only monitoring financial indicators such as revenue, profitability, and market share and ignoring other intangible indicators [

62]. Therefore, the measurement of only the tangible performance indicators of businesses has become insufficient for dynamic competition, has limited natural and talented human resources, and has widened environmental limitations [

63]. Consequently, business firms now need to account for sustainable performance measures, such as community satisfaction and ecological indicators, which must be applied alongside the usual financial-economic measures of profitability [

64]. Nevertheless, lately, private businesses have begun to take proactive steps to balance their high economic viability with their environmental and social performance in order to enable their firms to attain a high long-term sustainable performance, which is a sign of a more positive change [

63,

64,

65].

Early in 1969, The American National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) expressed an increasing interest in realizing the critical interaction between humans and the environment in response to these challenges [

66]. In 1987, the United Nations Brundtland Commission advocated the international endorsement of these principles. It offered the definitive and most frequently used definition of sustainable development: “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [

65]. Sustainability has become an effective term with various interpretations depending on the focus and knowledge discipline. Subsequently, sustainability is a multidimensional concept encompassing economic, social, political, technical, and environmental considerations [

67]. Nevertheless, since the Brundland Report (1987), the majority of scholars have agreed that sustainability may be divided into three categories, namely, economic, social, and environmental, with the balance between them in the framework of the company [

63,

64,

67,

68,

69,

70]. Additionally, sustainability strategies highlight business growth and high performance for the benefit of the public, society, and the environment [

71,

72]. In this context, previous studies revealed that social, environmental, and economic performance should be considered concurrently as one package, not independently, as a means of conducting business through profit making, contributing to enterprise performance, engaging in social harmony, and protecting the environment [

67,

73,

74,

75,

76]. With the growing attention to sustainable development, business firms must plan strategically and clarify how their operations positively influence the surrounding environment and the community [

77,

78].

Economic performance at the enterprise level is recognized as the capacity of a business entity to attain its short, medium, and long-term goals economically [

79]. Additionally, the traditional method of evaluating a company’s successful economic performance is to track conventional metrics such as the return on equity (ROE), return on assets (ROA), return on capital employed (ROCE), and return on sales (ROS) [

80]. In other words, the primary drivers of economic sustainability in business companies, mainly SMEs, are huge savings, high profitability levels, first-mover advantage, and strong competitive advantages [

81]. Thus, economic performance refers to business strategies that respond and react to market expectations by supplying products in a timely, efficient, and profitable manner to maintain or improve the overall quality of life [

82,

83].

Environmental performance usually refers to a company’s efforts to develop environmentally friendly practices and restore environmental conservation, including preserving the environment and ecosystems. Thus, environmental protection aims to sustain the natural ecosystem, such as the individual bodies and life support systems [

55,

84]. Moreover, the ecologically sustainable development of manufacturing SMEs and implementing friendly environmental strategies are essential to maintaining industrial rivalries and sustainability. Furthermore, In the manufacturing business, environmental performance also refers to activities that use natural resources to reduce environemtnally adverse effects [

85,

86].

An industrial firm’s environmental performance can be measured by its tendency to react, manage, and reduce the environmental emissions of CO

2, solid waste, water, and energy consumption. It also includes the firm’s dedication to minimizing the use of risky, insecure, and poisonous products and limiting the occurrence of accidents that harm the environment [

86,

87]. Subsequently, numerous measures have been used, including a reduction in energy, electricity, and resource consumption; a decrease in pollution and waste; conformance to environmental legislation; and the firm’s environmental image, which are all said to be beneficial [

73,

84,

88,

89]. Additional environmental performance variables to be considered by SMEs are ecology, environmental compliance with national and international standards, and other vital information, including environmental spending or the environmental effects of products and services, among other things [

89,

90]. As a result, the top management’s commitment and the distinguishing characteristics of senior executives will be essential for integrating the environmental standards of SMEs. Thus, firms will be able to achieve credibility and secure access to financial and nonfinancial resources by adapting and embracing the aspects of environmentally sustainable performance [

60].

In addition to the economic and environmental components of sustainability, social responsibility is the third critical component of sustainability that has received less emphasis in the literature; therefore, the interrelatedness amongst the environmental, economic, and social dimensions is fundamental to sustainability in developing, emerging, and developed countries [

91,

92]. With the customers’ growing need for businesses to demonstrate their compliance with social responsibility, achieving financial and environmental results is no longer sufficient. Therefore, successfully managing social performance concurrently with economic and environmental performance is crucial for managers, who must be aware of methods to effectively manage social performance [

91,

93]. Although social sustainability is far more difficult to evaluate than economic growth or environmental effects, it is the most overlooked triple-bottom-line-monitoring component compared to economic and environmental performance. Similarly, most social sustainability indicators are too broad to be practical, and customized measures for individual firms must be established [

94]. Thus, the pursuit of sustainability, primarily social sustainability, has already begun to reshape the competitive marketplace, forcing businesses to rethink their approaches to goods, technology, processes, and business models due to this transformation [

95]. Therefore, the primary purpose beyond social responsibility is preserving and conserving community cohesion. Hence, social performance is associated with the business strategies influencing the essential needs of the company’s investors, staff, neighborhoods, and societies [

83,

96].

Numerous studies in the management literature have investigated the factors influencing financial performance. Nevertheless, few studies have explored how manufacturing SMEs can prepare and implement long-term strategies to deal with sustainable performance challenges [

97]. Similarly, additional studies are still required, mainly empirical research in SMEs. Therefore, further studies are recommended to construct a typical combination of the three main dimensions of firm sustainability through the organization’s objectives, competitive advantages, and internal/external legality [

98,

99].

The attention to studying sustainable performance in business firms, specifically SMEs, has gradually evolved in recent years in developed and emerging countries [

100]. Yet, this measure needs further studies in different business sectors in developing countries. Similarly, the growth of the research into sustainable performance in SMEs is attributed to two main reasons: SMEs play critical and dynamic roles in developing nations’ economies. Hence, SMEs are required to deal with internal and external influences that influence the financial, social, and environmental results [

61,

101,

102]. The second reason entails the vital participation of SMEs in the attainment of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) at the country level [

82,

102,

103].

It is crucial to study how factors such as systematic strategic planning and strategic business innovation affect sustainable performance in a developing country with a turbulent environment and low firm performance, such as Palestine. Therefore, this research defines sustainable performance as a business’s capability to incorporate social, environmental, and economic factors [

104]. Thus, social, environmental, and economic performance are considered concurrently as one bundle, not independently, as a means of conducting business through profit making, contributing to enterprise performance, engaging in social harmony, and protecting the environment [

67,

73,

74,

75,

76], which could help discover practical recommendations and theoretical frameworks that help SMEs grow, thrive, and stay in business.

2.3. Systematic Strategic Planning (SSP)

Strategic planning is comparatively attractive as a research field in different organizations. It has been extensively employed in all kinds of businesses, such as manufacturing and services firms, and even in governmental and non-governmental sectors, until it became recognized as a crucial management pillar [

105,

106]. In a dynamic business environment, the capacity of businesses to adapt swiftly and effectively is a critical success factor that requires a clear strategy. Therefore, systematic strategic planning has grown to the point where its principal value is assisting firms in successfully operating in a dynamic and complicated environment and navigating increasingly unpredictable surroundings [

106,

107]. Systematic strategic planning, also known as formal strategic planning, is a series of interrelated phases, including strategy formulation, where internal and exterior aspects are subjected to careful study and diagnosis. This process includes the development phase of the strategy (including the mission, vision, strategic objectives, plans, and strategic alternatives), the implementation phase (the process of putting a strategy into action), and then the mentoring and evaluation phases [

27,

101,

108].

Systematic strategic planning enables firms to empower themselves by adding value and generating, discovering, strengthening, and overwhelming their competitive position in the market [

109]. Moreover, it equips leaders with proper arrangements and actions that should be employed to attain sustained competitive advantages [

110]. Likewise, all kinds of firms are requested to develop strategic plans that let them compete and survive; hence, top management should adopt and develop strategies using modern tools to achieve outperforming results. Moreover, companies are urged to frequently revise the surrounding internal and external atmosphere and modify their plans accordingly, in addition to conducting monitoring and evaluation, all of which are essential for the strategic planning process [

27,

109]. Hence, firms accomplish better performance and ensure sustainable performance at the financial, operational, and nonfinancial levels when strategic planning is formally and officially implemented [

106,

111,

112].

Despite the numerous research efforts in this arena, there are still several notable gaps in the literature, such as an examination of integrative models of the systematic strategic process, including analyzing all the phases as one package regarding sustainable performance. Clearly, the studies conducted in developing countries are limited, insufficient, inconclusive, and need to be further explored [

27,

40,

46,

113]. As a result, the purpose of this research is to test the influence of implementing systematic strategic planning on sustainable performance in the manufacturing SMEs in Palestine in order to conceive of recommendations and guidelines that may enhance the process of systematic strategic planning, which may lead to improvements and sustain the performance of such SMEs that are already encountering several issues that risk their existence and sustainability.

2.4. Strategic Business Innovation (SBI)

Most firms classified as SMEs face several limitations that impede their ability to invent new products and services, negatively impacting the attainment of a higher level of sustainable performance [

114,

115,

116]. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has created new problems and opportunities for manufacturing SMEs. Simultaneously, it has limited their capacity to sustain and maximize their output levels, requiring them to innovate and evolve by using innovation to increase their sustainable business performance and confront future problems [

24]. Equally, SMEs need to adopt the concept of invitation in business strategically. Otherwise, SMEs will be trapped in business by following old methods of producing and distributing their goods [

31].

The root cause of innovative constraints is mainly attributed to the associated threat to innovation, its complication, and the intrinsic ambiguity in implementing the invention. Also, the inadequate financial capabilities of SMEs and their limited access to financial resources compared with large-sized corporations is a major challenge to SMEs’ ability to innovate [

100,

110,

117]. Therefore, the owners and directors of SMEs are recommended to find creative solutions to overcome the obstacles mentioned above to engage in business innovation strategically, thereby improving their capacities to accomplish sustainable performance at economic, ecological, and social levels [

118,

119]. Therefore, adapting and deploying innovation in business activities as an essential strategic factor that impacts the performance of SMEs has become a key point of interest amongst researchers and experts.

Most of the prior empirical studies investigating innovation’s effect on SMEs’ sustainable performance revealed a positive influence on economic, social, and environmental performance. Yet, controversial results were found. Moreover, despite considering innovation in business activities with respect to companies’ progress, the researchers still did not reach a unified definition of an innovative company and innovation [

24,

120,

121]. Hence, more studies need to be conducted to investigate the effect of this vital driver on performance in different economies and different business surroundings [

40,

118,

122,

123]

The OECD’s Oslo Manual 2018 defines innovation as “a new or improved product or process that differs significantly from previous products or processes and is made available to users; innovation can be classified into four types: product, process, marketing, and organizational”. Moreover, the OECD claims that nations’ and firms’ adoption of the four types of innovation may help them hasten the retrieval and place countries on a sustainable path regarding economic growth, environmentally friendly operations, and satisfying society [

124]. Similarly, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) emphasizes the importance of innovation; the ISO recently developed the first edition of a specialized international standard that deals with establishing and implementing an effective innovation management system, IMS (ISO56000), which applies to all kinds of firms and organizations. According to the ISO Innovation Standard (2020), innovation is not about dazzling new technology or discoveries. Instead, innovation requires a firm to identify and explore new opportunities and react to environmental changes; it helps organizations achieve value while controlling uncertainty and using the workers’ skills and abilities [

125,

126]. Covin and Slevin (1989) defined innovativeness as “the willingness to place a strong emphasis on research and development, new products, new services, improved product lines, and global technology in the industry” [

126].

Subsequently, the firm that is the first to introduce specific methodological or technical changes is considered an innovator [

127]. Hence, firms need to understand and scrutinize the hidden dimensions of strategic innovation, precisely the innovation capabilities at all levels in the firms, mainly at lower levels, such as operations and the workers’ ability to provide details, openness, and inventiveness [

128].

The directors of SMEs must benefit from prior practices of other firms’ achievements and failures with respect to implementing business innovation. Learning from others allows SMEs to adopt the readiness to substitute the old-style nature of managing, recognizing, and encountering challenges while developing a resilient structure that quickly absorbs the learning process and implementation method of modern know-how and technology together with all kinds of innovation [

40,

129]. Equally, SMEs can adopt Business Model Innovation (BMI) as a crucial enabler to adopt SBI, which helps firms strengthen their competitive advantages in the new era of digitizing economic activities and transactions [

130]. Researchers and SME practitioners need to learn and focus on understanding the association of the main types of innovation in business, including managerial and product innovation. While simultaneously investigating their impact on the efficiency and growth of firms in different economies, the effects are not the same and vary from one business setting to another [

131].

Based on the previously reviewed literature, there are preconditions that firms should fulfill to implement sustainable business innovation efficiently and achieve sustainability: first, the preparedness of businesses to create new services or products; second, the capacity of firms to drive innovation; and finally, the attitude of companies toward inventing new processes, innovating new products, developing innovative distribution methods, implementing creative marketing methods, and developing innovative services.

Despite the importance of strategically considering innovation in business activities, prior researchers still did not reach a unified definition of an innovative company and the impact of executing SBI on the efficiency of firms. Hence, further studies need to be conducted to explore the impact of this vital strategic driver on performance in different economies and different business settings [

40,

118,

122,

123].

The previous empirical studies that focus on the impact of innovation on SMEs’ performance display debated findings and recommend scholars to conduct further empirical studies on the impact of innovative business strategies on sustainable performance in different business settings, economies, and countries. Specifically, such studies include those focusing on SMEs in the Arab region as a developing economy, since the number of prior studies in this regard is minimal and non-inclusive [

118,

127,

132]. Therefore, this research will be one of few studies dealing with strategic business innovation and systematic strategic planning as strategic components toward sustainable performance in Arab firms, mainly Palestinian manufacturing SMEs. Consequently, we developed a model to examine how these variables could influence sustainable performance and applied it. Moreover, the model investigated whether the variables are crucial in the context of Palestine.

This study adapts unitary variables from the literature, meaning that each variable is formed from a set of measurable items, for the following reasons. Firstly, the authors claim that multidimensional variables are more suitable for large enterprises. Large enterprises usually have a more significant number of employees, several hierarchical levels, and many specialized and large departments such as the innovation and R&D departments, corporate responsibility departments, corporate strategic-planning departments, etc. Thus, measuring the multidimensionality of such variables is logical for large business settings. Nonetheless, SMEs usually have fewer employees and specialized departments. Therefore, SMEs have a less formal systematic strategic-planning process and strategic business innovation focus and a less sustainable performance-monitoring process. Secondly, several studies have criticized the use of multidimensional variables for SMEs. For example, [

3] used both multi-item and uni-item scales to measure the theoretical constructs in their conceptual model. For instance, they measured the innovation scale via ten items: product innovation (two items), managerial innovation (two items), process innovation (two items), and market innovation (four items). On the other hand, they measured the performance scale through five uni-items.

This current study is different as it explores the variables at the strategic level. Thus, a unitary construct for the SBI scale is more appropriate for our study. Similarly, the literature also showed that the SSP and SP scales could be used as multi-dimensional or uni-dimensional scales.

2.5. Hypotheses Development

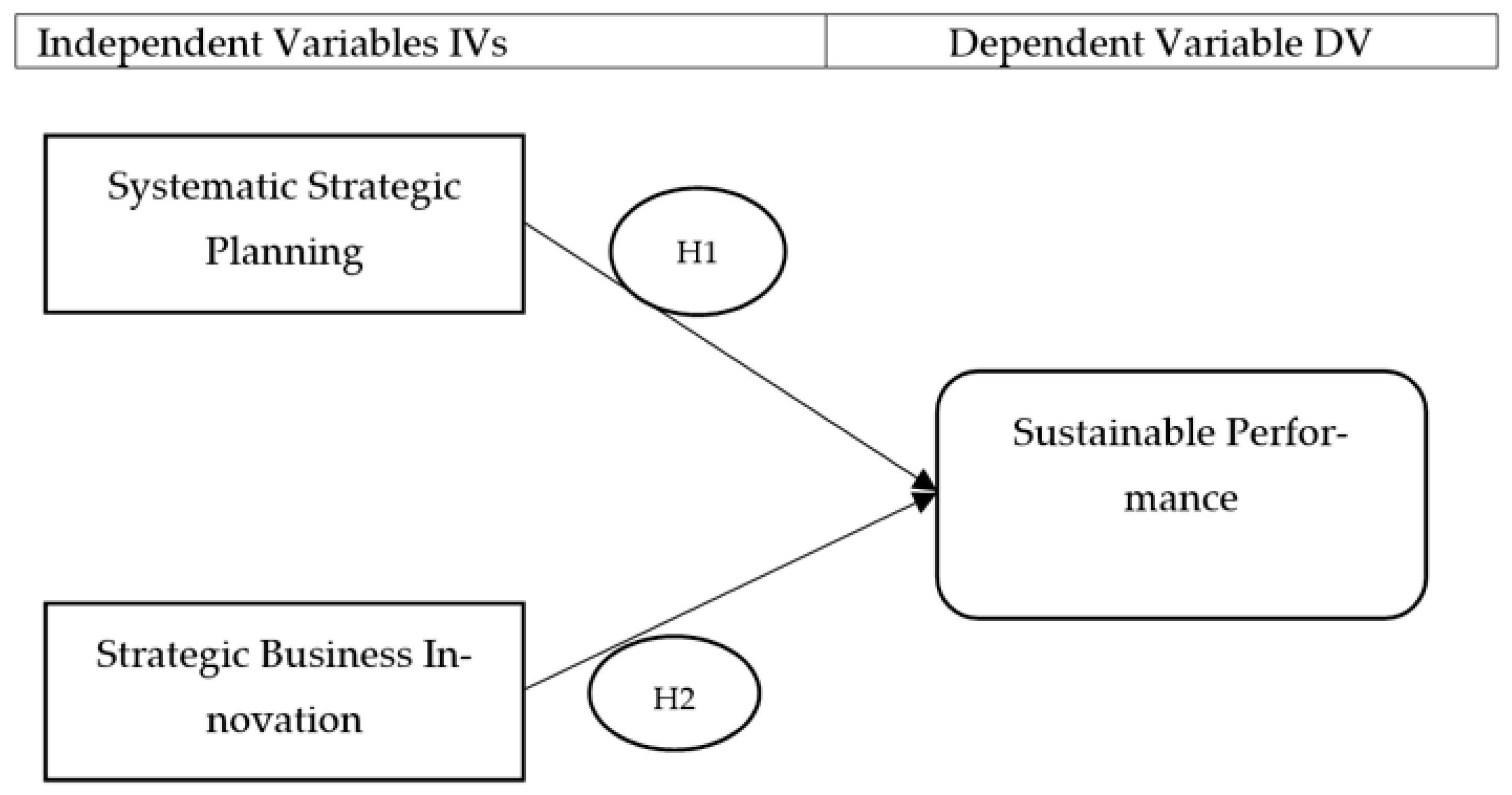

This study’s research model and hypotheses were developed and validated based on a thorough review of the literature to assess the capacity of the following variables: systematic strategic planning and strategic business innovation. Furthermore, this study explores how these variables are associated with the sustainable performance of the SME manufacturing sector in Palestine.

Systematic strategic planning was selected as an independent variable for several reasons. George, Walker, and Monster (2019), in a literature review of more than thirty related empirical studies, recommend that future studies need to explore the direct influence of strategic-planning formality on the effectiveness of an organization, which leads to sustainability [

106]. Secondly, most prior studies that explored the influence of systematic strategic planning on the performance and sustainability of business firms were conducted in the US, Western, and emerging nations, with limited studies completed in developing countries such as Arab countries [

3,

130,

131,

132]. Thirdly, the studies of the influence of systematic strategic planning on performance were primarily conducted on large corporations, such as IT, electronics, and consulting firms. However, very little research was performed on SMEs, mainly manufacturing SMEs in Palestine [

46]. Likewise, Palestinian manufacturing SMEs are among the leading importers of raw materials and one of the largest employment generators [

18]. Thus, this contextual gap requires more investigation. Lastly, the effective strategies derived from proper SSP have also been seen as an intangible resource that may offer a competitive advantage to business firms [

57].

For these reasons, further empirical research is needed in Palestine to verify the previous results regarding the link between systematic strategic planning and sustainable performance. Moreover, the Palestinians’ different surroundings, their way of practicing business, and the nature of their culture may help discover new insights into this connection. As a result, the study’s hypothesis regarding systematic strategic planning is as follows.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Systematic strategic planning positively influences sustainable performance in manufacturing SMEs in Palestine.

On the other hand, Palestine is not listed as innovative on the Global Innovation Index [

133]. Likewise, according to the business performance classification of the World Bank, it is considered a nonattractive country for foreign investors [

13,

18]. Therefore, the study analyzes strategic business innovation and provides a framework for conceptualizing it in several distinct ways. This could provide numerous recommendations at the policy level to support manufacturing SMEs in Palestine.

In conclusion, in previous studies on strategic business innovation, there were several reasons why SBI was chosen as another independent variable. First, AlQershi et al. (2018) recommend exploring the influence of strategic innovation on the performance in Arab manufacturing SMEs to extract suggestions to enhance performance at the policy and company levels [

118]. Second, most of the prior studies focused on investigating the links between executing strategic business innovation and traditional financial performance, e.g., [

118,

129,

134], whereas this study will expand the concept of performance by investigating the effect of implementing strategic business innovation on sustainable performance. Third, most strategic business innovation studies were conducted in developed and emerging nations, with only limited studies completed in Arab countries, which are largely considered less developed [

40,

132,

135]. As a result, this study’s related hypothesis to strategic business innovation is as follows.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Strategic business innovation positively influences sustainable performance in manufacturing SMEs in Palestine.

Based on the above rationale, this study uses uni-item scales to measure the three theoretical constructs: SP, SSP, and SBI. The SP scale is adapted from [

111,

136], as shown in

Appendix A, is measured by nine items. The SSP scale is adapted from [

137] and measured by seven items, as shown in

Appendix B. The SBI scale is adopted from [

40,

138,

139] and measured by seven items, as shown in

Appendix C. These items were used to measure each construct in the same way they were measured by the stated past studies for the same constructs. They were also used for collecting data from similar respondents in an SME context.

Figure 1 below shows the theoretical framework developed for this study.