Abstract

Sustainability has been discussed as a constant market concern, and to make it effectively an organizational practice, specific skills are needed. In that sense, the objective of this study is to analyze the relation between organizational competencies and the development of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria in the industrial sector. A scientometric methodology was used to analyze the production of scientific research on the topic. To define the portfolio, a search was performed using the Methodi Ordinatio technique in the Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science databases using the terms “organizational competencies” or “environment, social and governance*” or “ESG” and “industry”. The study period was from the beginning of the database indexing until May 2021. The results indicate that the topic is relevant to the area of study due to the continuous growth of publications and global concern with ESG issues. In this sense, the industrial organizational competencies highlighted in the development of ESG include corporate social responsibility (CSR), and technical, managerial, and commercial competencies. The analysis demonstrates the positive relationship between organizational competencies and sustainable development, and the discussion is directed at the competencies that fortify ESG criteria and practices in industry.

1. Introduction

ESG is a new term that is based on the concepts and concerns of the tripod of sustainability, also known as the Triple Bottom Line. ESG expands the scope of governance, providing greater visibility for those directly involved with the organization’s growth. Thus, the criteria for defining ESG are environmental (E), social (S) and governance (G), and their analysis refers to the practices surrounding environmental conservation, relationships with stakeholders, and corporate administrative issues [1,2,3].

ESG criteria are considered by investors, governments, shareholders, and organizations with regard to environmental and social issues and those of economic interest to organizations [1,2]. An ESG refers to returns on sustainable business practices, environmental risk reduction, and aspects related to responsible investment [3]. In defining financial investments, market participants demand sustainable development that considers ESG factors [4].

In the decision-making process, ESG variables are used to select suppliers and choose investments [5]. The institutional visibility of organizations that perform ESG practices and are concerned with responsibilities to their stakeholders are preferred by investors in stock markets [6]. Meanwhile, [7] pointed out the individual preferences of the market for ESG factors. The authors of [8] identified the impact of ESG performance on financial risk and argued that ESG performance is a balancing mechanism between stakeholders, risk management, and corporate legitimacy; those that achieve a reasonable performance in ESG criteria present lower total risk.

ESG consists of parameters adopted by many investors who analyze the activities of companies and make decisions based on the related information provided in reports or corporate balance sheets [6,9,10,11]. Integrating the global reporting initiative (GRI) into the business model is an option to present value-added projects to stakeholders, disseminate a company’s everyday practices developed around ESG criteria, and influence competitive advantage at the corporate level [12]. Content analysis of such reports provides information on risk and corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, stakeholder engagement, and environmental policy [13], as well as the quality and quantity of information communicated in relation to ESG [10]. For [8], the information described and addressed by ESG indicators informs all stakeholders about a company’s actions and responsibility, offering investors greater clarity in the decision-making process.

ESG rating agencies contribute to sustainable development by selecting corporations with ESG criteria that consider sustainable principles in their daily processes and practices [14]. Financial analysts rely on ESG to verify corporate responsibility as market demand and investment signals [15]. In this sense, [13] noted that organizations identify risk in relation to ESG factors and company reputation and develop social responsibility strategies to mitigate these risks.

As such, corporations are implementing ESG practices to access new financial markets, growth opportunities, and differential competitive strategies [1,2]. The demands of ESG are directed at a holistic view of business management, as they require the development of environmental, social, and governance indicators and therefore have an impact on financial performance and strategies for organizational survival [6,16,17,18,19]. There is a positive and proactive relationship between ESG indicators and a corporation’s superior performance, considering that ESG investment processes add value in the long term [5,6].

The strategic management of an organization involves the development of specific skills and competencies and the training of managers, individuals, and the organization as a whole. To survive, it is essential to improve skills and competencies, because employees must have the capacity to enter new markets, respond immediately to adversities, solve problems, reduce costs, and improve operational efficiency, market transparency, trust, and credibility [20]. These indicators can be identified by analysts and business shareholders across the three dimensions of ESG [4].

General competencies are directly linked to ESG through improved performance, in which organizations seek to be more efficient and effective in their processes, products, and services. In this context, they must have the available competencies to improve their financial and non-financial performance. The purpose of ESG is to achieve positive results in the social, environmental, and governance dimensions, which is realized through the skills of individuals and the conditions provided by the company, that is, through the set of competencies held by the organization.

Therefore, in this study, we consider organizational competencies as a set of competencies formed by individuals and the organization. Given the interrelation between them, organizational competencies are conceptualized as a set of key factors that belong solely to the corporation, thus making it unique [20], and individual competencies are defined as the skills, knowledge, and creativity used by individuals as they perform various tasks [21].

Organizational competencies are necessary for economic activities that require distinct resources, skills, and qualities of managers and others involved in an organization’s processes [20]. The importance of performance measurement is based on emotional and social skills, as they positively influence the ability to leverage the capacities, skills, and creativity of individuals in the business environment [21]. In [20], the authors argued that organizational competencies enable strategic responses to change, task coordination, and the efficient operation of interdependent systems. As such, political skill is a key factor in the success of the efforts of change agents [22]. To develop organizational competencies, discussions must be directed toward understanding what they mean, internalization by collaboration, and adherence to the strategic group [23].

The competencies needed to advance in terms of ESG criteria include: systemic thinking; learning capacity; attending to values and ideals; culture transformation; alternative business formats; supporting collective solutions; incremental, radical or systemic innovation; creating networks; and capacity to collaborate [24]. These skills can be classified as basic, intermediate, and dynamic and depend on the sector and the innovation of competitors [25]. The processes of knowledge generation in the formal and informal practices of corporations encompass the organizational, social, and technical criteria of those involved [26]. Negotiation skills with customers, suppliers, commercial issues, technological innovations, and sustainable development are only employed when they are understood, practiced, and are part of the organizational culture [21].

Employee engagement occurs more frequently when individuals perceive the essence of their work in the organization, and their engagement is spontaneous, simultaneous, and proactive. In addition, employees are more willing to engage with the company’s objectives if they perceive practices that demonstrate the company’s concern for their wellbeing, provide the tools necessary for work, and recognize and value their commitment [27]. Social engagement is part of the teaching–learning practices by business leaders [28].

In the software industry, for example, programming products that facilitate routine work activities of companies and people have been increasing, and their success is dependent on both performance and the casual circumstances of market opportunities. Success factors are based on basic characteristics of competencies, such as infrastructure and education, culture, and social networks, as well as aspects that are difficult to imitate, considering organizational competencies [29]. Organizational culture is an essential element that directs the collaborative and behavioral skills of an organization in cultivating and managing its affective ties with institutions and agents, or its capacity for innovation and relationship building, variables that have an impact on how the market perceives performance [30]. Organizational skills are essential in understanding the interdependence between societies and organizations, their ability to deal with adversities, and the constant pursuit of dialogue with stakeholders [31].

The leadership as a social intelligence component allows managers to have the capacity to perceive, interpret, and act in various social and cultural situations resulting from the behavioral praxis of individuals [32]. The effectiveness of their leadership increases as they perceive the complexity of problems, acquire holistic understanding skills to position themselves, use social reasoning and dynamic relational and interpersonal skills to make decisions, and converse with leaders. An accurate positioning of responding and commanding contributes to organizational efficiency. A leader’s abilities are different depending on the organizational level in which they act; however, a leader must possess cognitive, interpersonal, business, and strategic skills [33].

Competencies are measured by CSR indicators as disclosed in reports, which include the size of the company and the sectors that are most sensitive to and influenced by information about practices implemented in terms of social responsibility to employees, customers, and the community in general [34]. The integration of organizational competencies directed at sustainable principles highlights the confluence between individual and organizational objectives [35]. One study analyzed the interrelations between sustainable development and organizational skills, and highlighted the need for differentiated network of relationships, management of triple bottom line concepts, and product renewal to improve reputation and brand legitimacy, while simultaneously seeking to combat inequality and poverty [36].

Therefore, industries can develop new products, implement energy saving strategies, reduce resource use and strive for zero waste, alongside which the development of internal skills and competencies adds value to the corporation’s business through practices related to environmental, social, and governance concerns. In this sense, developing organizational skills in consideration of ESG in various industries worldwide can lead to expansion into new markets and attract new investors through the implementation of sustainable projects in a company’s productive operations.

Several studies on organizational competencies have been published over the last several years [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. While other studies have correlated organizational competencies with performance and value added [46], knowledge management [47], dynamic capacity [48,49], organizational learning and innovation [50,51,52], organizational culture [53,54], organizational excellence [55], organizational creativity [56], digital transformation [57,58], and organizational performance [58]. Previous studies have indicated that competency relationships are more strongly focused on the internal structure of organizations. Therefore, expanding the focus of analysis to external interrelationships, such as ESG, requires new constructs.

To fill this gap, the study aims to analyze the relationship of organizational competencies in the development of ESG parameters in the industrial sector. The problem addressed in the study is: what are the organizational competencies that promote the growth of ESG parameters in industries? In addition, we considered how organizational skills can be targeted to attract new investors, contribute to improved environmental practices and use of resources, develop socially relevant action plans, and enhance reputation and market image to capture investment for global industries.

2. Materials and Methods

The research methodology adopted is a systematic literature review of studies indexed in the Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science databases that focuses on organizations and ESG (environmental, social and governance) criteria over the period from the beginning of the database indexing until May 2021. The method applied was Methodi Ordinatio, which categorizes articles by impact factor (IF), number of citations, and year of publication [59,60].

Methodi Ordinatio has nine phases, which were applied in the study: Phase 1—establish the purpose or intention of the study; Phase 2—initial exploration in the databases by searching for keywords; Phase 3—define the combination of keywords and databases. The parameters and search filters applied in the present study are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Keywords and filters applied in search. Source: research data.

The industrial sector considered in this study refers to all types of economic entities belonging to the first, second, and third sector that are classified as producing goods, capital, and consumption, and they were chosen because this sector is a source of economic growth [61]. The most prominent industries in the study are classified as other industries, services, and clothing and textile industries. The nomenclature of other industries is used, as the sector is not specified.

In Phase 4, the results from the search described in Table 1 are defined. Based on the applied filter, the Web of Science presented 120 articles for subsequent analysis, while no results were found in Science Direct. In Phase 5, the data are filtered to exclude duplicate articles using Mendeley Reference Manager. We also excluded all studies published as books, chapters, and conference proceedings, as well as those that do not address the topics of focus in this study. Table 2 presents the filtering process that was applied to the data.

Table 2.

Exclusion of articles by type of document. Source: research data.

In Phase 6, the scientific relevance of the journals is classified by impact factor (IF), as verified in the journal citation reports (JCR). For journals without a JCR, a sequential parametric ranking is applied chronologically by CiteScore, SCImago (SJR), and Snipp. For journals with none of the cited rankings, the value attributed was zero. The number of citations was collected from Google Scholar, and subsequently, the year of publication was verified. After data collection, the InOrdinatio equation of Methodi Ordinatio was applied [59,60].

InOrdinatio = (IF/1000) + α × [10 − (ResearchYear − PublishYear)] + (∑Ci)

IF: impact factor;

α: weighted factor that varies from 1 to 10, attributed by the researcher based on the theme;

Research Year: year in which the research was developed;

Publish Year: year in which the article was published;

Ci: number of times the article was cited.

In Phase 7, the impact factor (IF), number of citations (Ci), and year of publication of all articles in the final portfolio were identified. With the available information, the InOrdinatio equation was applied. The key metric selected was the JCR, followed by SJR and CiteScore. For journals without any informed parameters, a value of zero was given.

In Phase 8, with the InOrdinatio equation, the relevant articles based on the study theme are defined, and from this, in Phase 9, the complete articles are obtained for analysis and to collect the bibliometric data of the studies. As such, articles were found and downloaded for analysis.

The bibliometric analysis of the data tracks the evolution of the topic over time, maps the most common keywords, provides a network map of the main authors using the VOSviewer software, and identifies the countries of publication, the institutions developing the research, the journals that publish most frequently on the topic, and representation by sector.

To complement the bibliometric data, a content analysis was conducted using a framework to provide information about organizational competencies. The content analysis sought to identify the main competencies addressed in the articles that can be developed and matured to improve ESG parameters in industries, defining the authors, competencies, factors that affect the process, and possible solutions.

The content analysis of the study was carried out following the guiding models that emphasize the pre-analysis of the material to separate and prepare documents for the subsequent phase of analysis, in which the material is classified into units, and finally treatment of results, inference, and interpretation [62]. In this sense, data analysis selected possible competency indicators based on specific terms, separating them for treatment and categorization. The competency terms that did not receive a classification unit were grouped into the “Business Intelligence Capacity and Mission Profile Competencies” while the others considered the specific terms used in the manuscripts.

The following section provides the results and discussion arising from the applied methodology.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

The systematic literature review selected 69 articles, with five presenting the greatest number of citations and highest coefficients in the InOrdinatio equation, as follows: 1—“IT competency and firm performance: Is organizational learning a missing link?” with 2409 citations and an InOrdinatio score of 2329.005471; 2—“Leadership competencies for implementing planned organizational change” with 429 citations and an InOrdinatio of 419.006642; 3—“Information technology competencies, organizational agility, and firm performance: Enabling and facilitating roles” with 349 citations and an InOrdinatio of 369.003585; 4—“Managing organizational competencies for competitive advantage: The middle-management edge” with 390 citations and an InOrdinatio of 290; and 5—“Influence of leadership competency and organizational culture on responsiveness and performance of firms” with 239 citations and an InOrdinatio 229.005667. The selection of the top-ranked articles points to the direction and importance of the relevant issues on the topic.

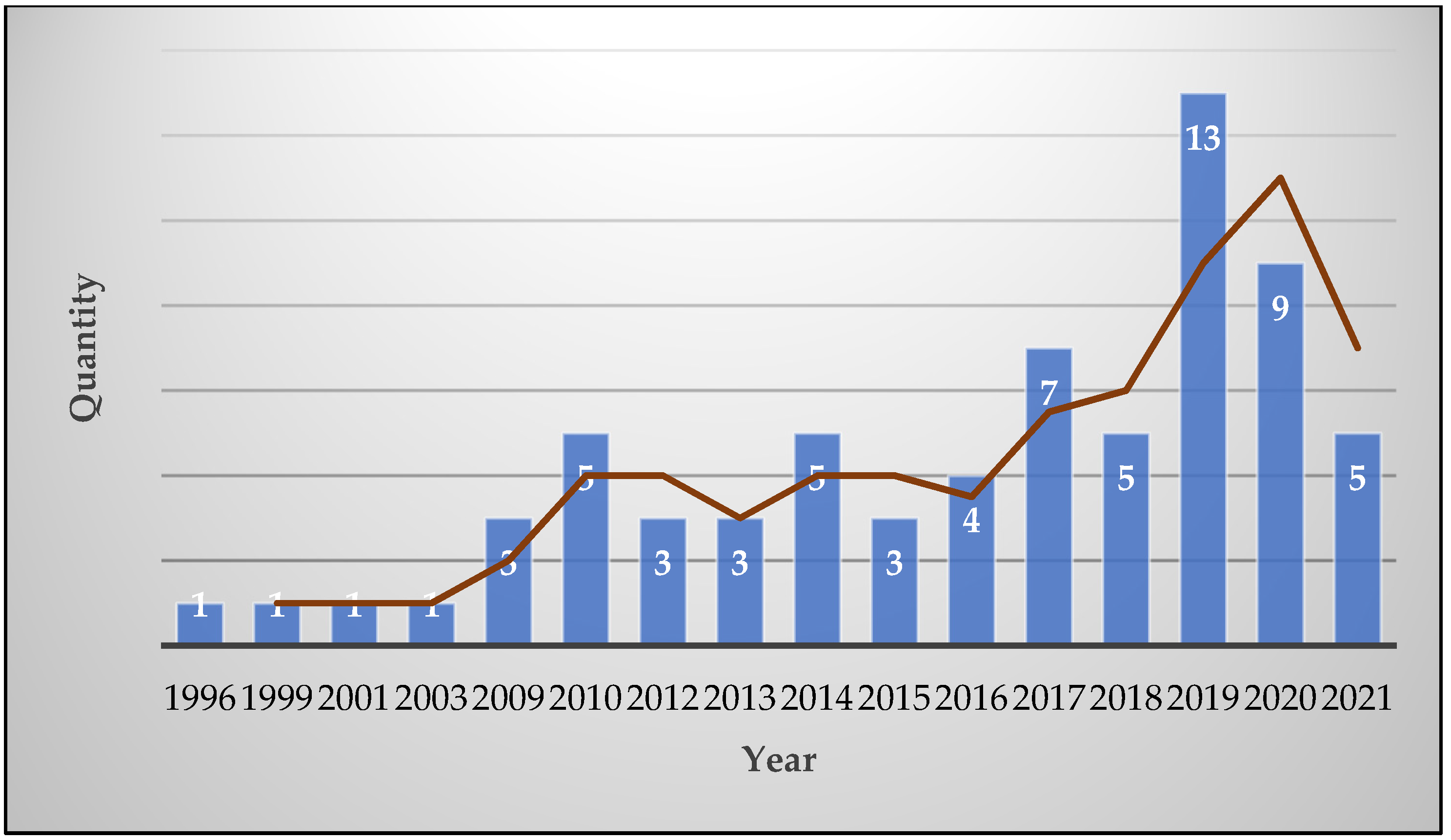

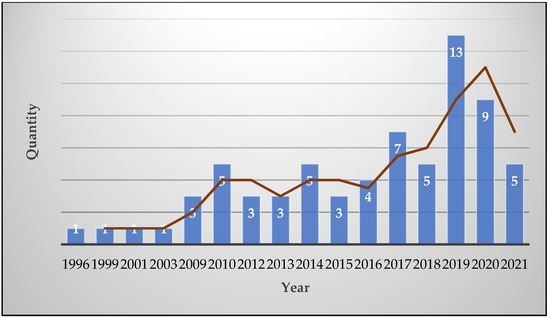

The bibliometric analysis shows that the topic of organizational competencies related to ESG is evolving. The concept of organizational competency is more common and has more publications than ESG, which is still a new idea, and the term is used less often by researchers in comparison to the word sustainability. Studies on the researched topic were first published in 1996, with a general growth over the years, reaching a peak in 2019, with 13 articles.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between the studied topic and growth in number of publications per year.

Figure 1.

Yearly growth of publications on the theme. Source: research data. The figure line represents the trend line cutoff.

As the trend shows that studies in this area are growing, we can see that the evolution of research in the area is extremely relevant. Both topics contribute to the growth of industry, with the development of organizational competencies having a direct influence on the scope of ESG criteria when industries implement actions that are already within their range of competencies. According to [63], industry is concerned about the increasing demand for more sustainable products; therefore, traditional business practices are being overcome, and companies are investing in the integration of ESG strategies. The authors of [2,4] argue that sustainable development must achieve a balance between human activities and ecological and social issues.

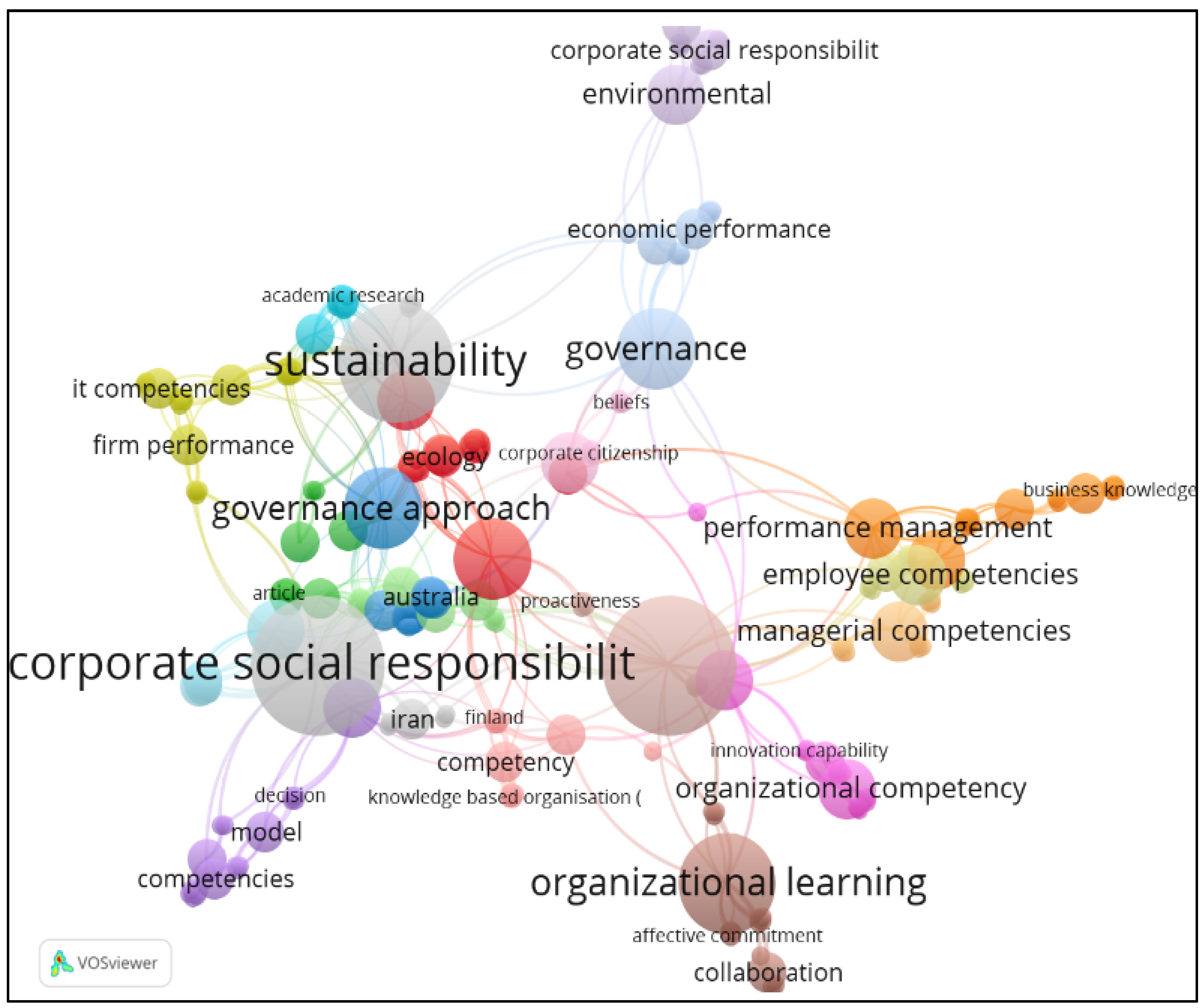

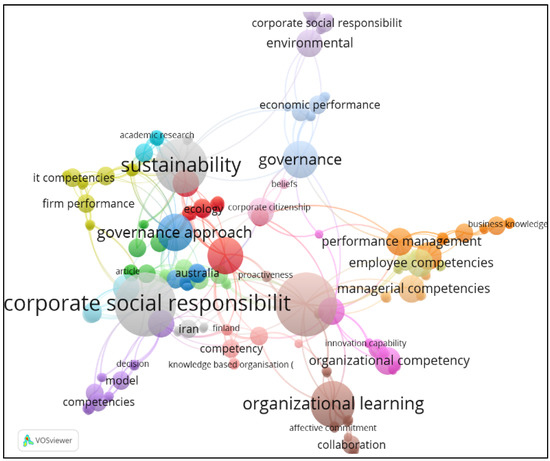

The main keywords demonstrate that the topic addressed is related to the following issues: corporate social responsibility (CSR); sustainability; organizational learning; governance approach; governance; organizational competence; managerial competencies; employee competencies; performance management; competency; knowledge-based organization; innovation capacity; proactiveness; decision making; corporate citizenship; affective commitment; collaboration; firm performance; and environment. A keyword map was developed using the VOSviewer software with the criteria of at least two connections to form a network.

Figure 2 presents the keyword map.

Figure 2.

Map of keywords. Source: research data.

The map contains four large network clusters, which are linked to smaller networks. The largest network is made up of the term CSR, with the second largest being sustainability, followed by organizational learning and governance. Therefore, when analyzing the overarching concepts outlined in the articles, we can see that CSR involves actions that demonstrate commitment to environmental, social, and ethical issues while also considering economic development. Such approaches must be learned by every organization and are included in managers’ strategic plans.

The first network is connected to the second, sustainability, and is directed toward actions and practices of organizational learning. According to [64,65,66], changes in behavior make industries more responsible in their actions with regard to social issues, environmental protection, and economic development. The publication of the CSR reports helps to gain political legitimacy inside and outside the business context [67], while the organizations treat internal corporate social responsibility (ICSR) as Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [68].

The third network is formed by key issues such as capacity for innovation, organizational skills, collaboration, knowledge, and affective commitment, among others. The connection between the networks reveals that an organization that has the capacity to learn uses competencies, collaborations, and innovations to improve its performance, implementing ESG criteria through CSR practices. Advanced technology helps to make processes more sustainable [64], emphasizing the importance of employee engagement and wellbeing in sustainable business management [68].

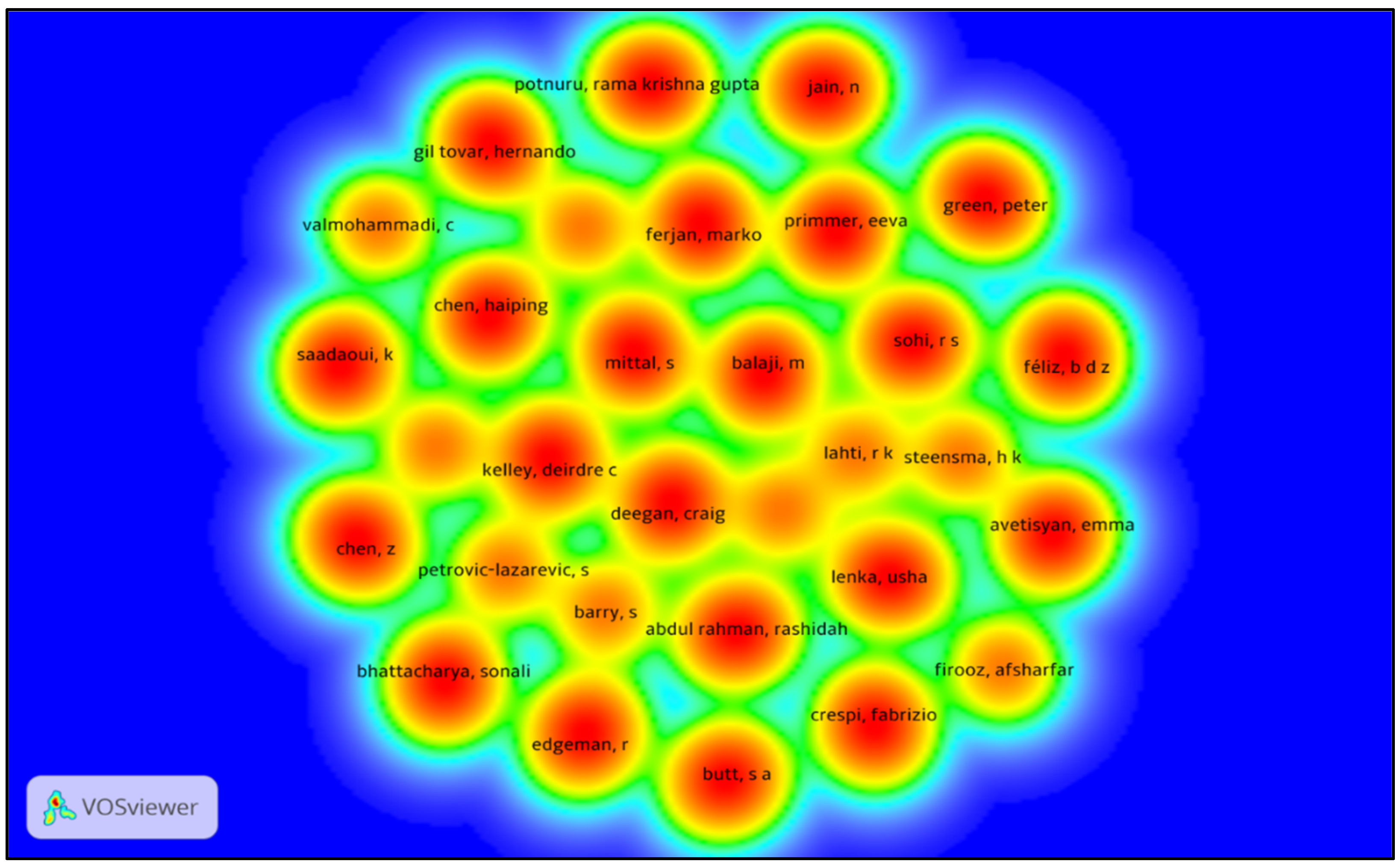

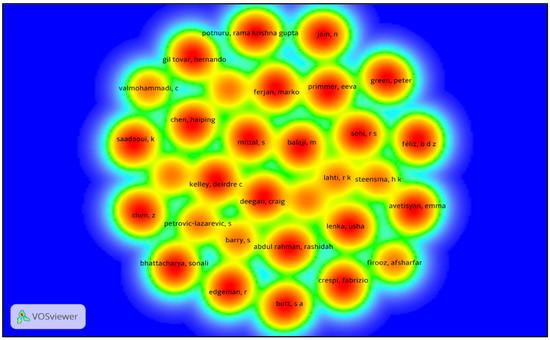

The network of researchers mapped by the VOSviewer software identifies the interaction between researchers and their efforts to publish on the topic through the development of research on organizational competencies and their influence on achieving ESG criteria in corporations. The network highlights the clusters or groups of researchers that contribute most frequently to the topic addressed herein, demonstrating their strong connection across the network.

Figure 3 shows the network density constructed by the authors through co-authorship and co-citation and their connectivity.

Figure 3.

Map of the network of researchers. Source: research data.

Figure 3 presents the main authors contributing to the studied topic, including: Potnuru and Sahoo; Jain; Gil Tovar and Lara Figueroa; Gorenak and Ferjan; Primmer and Wolf; Prasad and Green; Saadaoui and Soobaroyen; Chen and Ma; Singh and Mittal; Balasubramanian and Balaji; Tippins and Sohi; Nevárez and Féliz; Chen and Hamilton; Merritt and Kelley; Kamal and Deegan; Bhattacharya and Sharma; Edgeman and Williams; Abdul Rahman and Alsayegh; Syed and Butt; Naim and Lenka; Crespi and Migliavacca; Avetisyan and Hockerts.

The studied topic shows an increase in publications in 2019 with 13 articles, and the authors who contributed to the advancement of the topic were: Ionescu et al.; Potnuru et al.; Oliveira et al.; Fitri et al.; Nevárez and Féliz; Palacios-Marques et al.; Otoo; Mar Miralles-Quiros et al.; Mehralian et al.; Bhattacharya and Sharma; Kansal and Jain; Shet et al.; Singh and Mittal.

The institutional links and connections of these researchers include the following universities: University of Craiova and Romanian-Americana, Romania; Institute of Business Excellence, School of Technology, and Foundation for Technology and Business Incubation, India; University of Southern Santa Catarina, Brazil; Faculty of Economics and Business Universitas Yarsi, Jakarta, Indonesia; School of Technology Management and Logistics, College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia; Faculty of Engineering, Tridinanti University of Palembang, Indonesia; Universidad Autónoma de Occidente, Colombia; University of Valencia, Spain; Faculty of Business and Accountancy, Malaysia; University of Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain; University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; International University, Pune, India; Snow & Avalanche Study Establishment Chandigarh, India; University, Mumbai, Hubballi, and Bijapur, India; University of New Delhi and Kochi, Kerala, India. The interactions of researchers in 2019 was particularly significant between Universities and Research Institutes in India.

As for the journals that published the most articles on the topic, we found that each of the following journals had a frequency of 2.89% (n = 2): Sustainability; Social Responsibility Journal; Journal of Engineering and Technology Management; Journal of Business Ethics; and the European Journal of Training and Development. All other journals represent a percentage of 1.44% (n = 1). Of the journals that published the most on the topic, it is clear that Sustainability, Social Responsibility Journal, Journal of Engineering and Technology, and Management Journal of Business Ethics are publishing studies on organizational competency issues for ESG in industries, and the list of journals is consistent with issues of CSR, sustainability, engineering, technology and management, and ethical business practices.

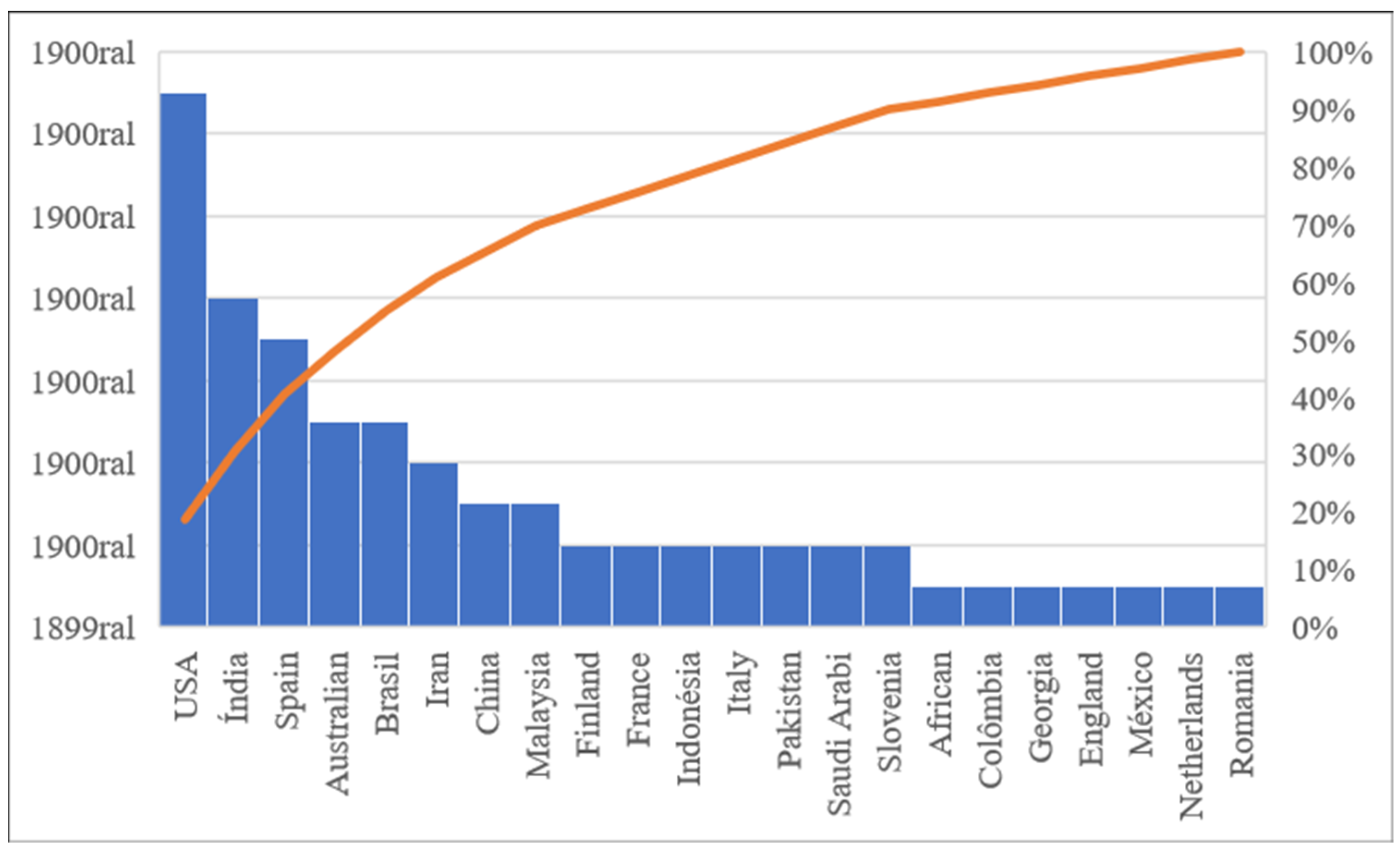

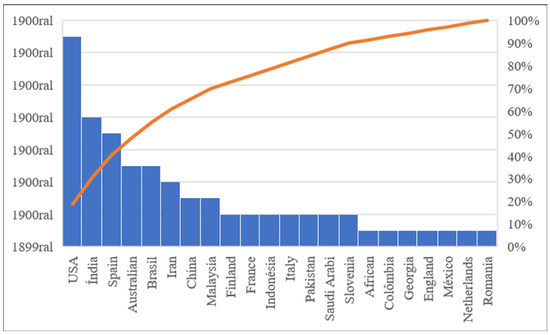

Country representativity was determined according to the country of origin of the first author of the articles in the portfolio. Researchers from the United States led studies on organizational competencies and how the topic positively influences the development and growth of ESG criteria.

Figure 4 shows the participation of each country by percentage.

Figure 4.

Country Representativity. Source: research data. The line of the figure refers to the main trends towards its representativity.

The country with the highest percentage of articles in relation to the portfolio is the United States at 18.84% (n = 13), followed by India with a representation of 11.59% (n = 8), and Spain with 10.14% (n = 7). Fourth and fifth in the ranking are Australia and Brazil, each with a percentage of 7.24% (n = 5), with the remaining countries contributing a lower percentage of authors conducting research on the topic.

The area of study, or the category in which the articles were identified, is mainly within the scope of business finance, psychology, ethics, strategy, and environment, representing 23.18% (n = 16). The second most relevant area of study is management with 13.04 % (n = 9). The area of sustainability, also linked to sustainable development and sustainable economic development, together with industrial engineering and its derivatives in technology management and manufacturing, represent 7.24% (n = 5). The next most relevant area is information and knowledge management, information studies, and information systems with a frequency of each of 5.79% (n = 4). These five major areas of research represent more than 55% of all identified fields of research in the portfolio.

The most predominant industrial sector is other industries, representing 42.02%, followed by the services sector with 24.63%, and textile clothing and information and technology.

Table 3 outlines the number of industries and the sectors in which they operate.

Table 3.

Representation by industrial sector. Source: research data.

Industries classified as “pollution” are those that produce high levels of pollution, and “sensitive” industries are those more attuned to caring for and preserving the environment, as they are not heavy polluters.

Based on Table 3, “Other industries” has the highest frequency of all classified industries, with a subsequent emphasis on service industries. The provision of services focuses on humans, offering improvements to their wellbeing and quality of life, and they are directed at organizational structure, service delivery technology, and quality assurance [69].

In their decision making, investors are considering companies and industries that seek to switch to renewable energy sources, conduct processes aimed at resource conservation, minimize pollution, and reduce carbon emissions, in addition to those that use ecological products and services [2,3,4,10].

3.2. Content Analysis

The content analysis reveals the main organizational competencies highlighted in the industry that drive actions and projects toward ESG.

Table 4 presents the factors identified by the authors that influence the promotion of the set of competencies for leveraging ESG in corporations.

Table 4.

Content analysis on organizational competencies. Source: research data.

In relation to Table 4, the organizational competencies that stand out in the industrial sector are corporate social responsibility (CSR) representing 18.84%, followed by technical, managerial, and commercial relevant competencies with a frequency of 10.14%, and thirdly, the essential competencies required to publish ESG reports and strategic and behavioral organizational leadership competencies at 6%.

Competencies contribute to the systematic understanding of activities and the realignment of functions and processes in decision making [23]. Emotional and social competencies affect the performance of activities and duties at work and argue that managers must adopt a feedback approach to lead and guide their employees [21].

Organizational competencies include: propose and implement improvements, visualize opportunities, threats, and trends, capacity to understand and act on the established strategy, systemic vision, decision making, and innovation to achieve sustainability in organizations [23], social engagement and teaching–learning practices [28], and differentiated relationship networks, products, and the key concepts of sustainable management [36].

An organization that follows the pillars of CSR increases its concern with differential and innovative products, is better able to satisfy needs, and has greater market visibility and attractiveness [66]. Apparel industries highlight the need for codified and shared knowledge, skills, and organizational capacity to develop new know-how and innovative competencies to remain strategically competitive [25]. The relationship between competencies and ESG reflects the constant improvement and confluence of individual and organizational objectives aimed at sustainable business [35].

Therefore, organizational performance is measured by operational work practices and the development of daily activities in an industry that is closely linked to organizational and individual competencies. This congruence and positive feedback demonstrate the correlation between organizational competencies and ESG criteria. It also accentuates that a country’s development is linked to organizations, which consequently require a set of skills to grow and respond efficiently to contingencies and adversities.

4. Conclusions

The objective of the study was to analyze the relationship between organizational competencies and the development of ESG (environmental, social and governance) criteria in the industrial sector. Based on our analysis, the topic has been evolving since 1996 and has become more prominent since 2019. The country that published the most research on the topic was the United States with 18.84% (n = 13), followed by India with 11.59% (n = 8). The keyword network map was formed by four large clusters around CSR, sustainability, and organizational learning, and governance. All word networks highlight concern for the environment, social and ethical issues, and economic development. These perspectives are included in the ESG criteria, which are affected by actions and practices within a culture of learning and organizational innovation.

The journals with the greatest number of publications are Sustainability, Social Responsibility Journal, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, Journal of Business Ethics, and the European Journal of Training and Development, each representing 2.89% (n = 2) of the portfolio. The most relevant area of study in which the articles are published is business finance, psychology, ethics, strategy, and environment, representing 23.18% (n = 16). The majority of studies focus on other industries, representing 42.02%, followed by the service sector with 24.63%.

The organizational competencies highlighted in the studies to foster the development and maturation of ESG are CSR (which include actions carried out by industries focused on people, the environment, and management), with a percentage of 18.84%, followed by technical, managerial, and commercial competencies (which include supporting the development of organizational activities), with a frequency of 10.14%.

The main limitation of the study was a lack of statistical tests to detect the strength of the correlation between organizational competencies and advancing the practice of ESG criteria worldwide. Nevertheless, this offers an opportunity for future research using statistical analyses to verify the results identified in the content analysis for the management of organizational competencies.

The value of the study is in its consideration of the organizational competencies that enable the development of the practical criteria of ESG in industry, offering a preliminary reflection upon which further research can be developed to assess the direct relationship between organizational competencies and ESG criteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, M.S., L.A.P. and P.R.; software, M.S.; validation, M.S., L.A.P. and P.R.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.S.; resources, M.S., L.A.P. and P.R.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S., L.A.P. and P.R.; visualization, L.A.P. and P.R.; supervision, L.A.P. and P.R.; project administration, L.A.P.; funding acquisition, L.A.P. and P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Federal Techno-logical University of Paraná (UTFPR).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tarmuji, I.; Maelah, R.; Tarmuji, N.H. The Impact of Environmental, Social and Governance Practices (ESG) on Economic Performance: Evidence from ESG Score. Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2016, 7, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minutolo, M.C.; Kristjanpoller, W.D.; Stakeley, J. Exploring environmental, social, and governance disclosure effects on the S&P 500 financial performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Zulkifli, N.; Zainal, D. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) and Investment Decision in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senadheera, S.S.; Withana, P.A.; Dissanayake, P.D.; Sarkar, B.; Chopra, S.S.; Rhee, J.H.; Ok, Y.S. Scoring environment pillar in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) assessment. Sustain. Environ. 2021, 7, 1960097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Finance Investig. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting in China. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2014, 23, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, B. ESG preferences, risk and return. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2021, 27, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.H. Environmental, social and governance performance and financial risk: Moderating role of ESG controversies and board gender diversity. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel-Zadeh, A.; Serafeim, G. Why and How Investors Use ESG Information: Evidence from a Global Survey. Financial Anal. J. 2018, 74, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Sajjad, A.; Farooq, S.; Abrar, M.; Joyo, A.S. The impact of audit committee attributes on the quality and quantity of environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosures. Corp. Governance: Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 21, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttipun, M. The influence of board composition on environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure of Thai listed companies. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2021, 18, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaya, A.J.; Saleh, N.M. The moderating effect of IR framework adoption on the relationship between environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure and a firm’s competitive advantage. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 24, 2037–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M.; Raulinajtys-Grzybek, M. The application of corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions for mitigation of environmental, social, corporate governance (ESG) and reputational risk in integrated reports. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1270–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á.; Ferrero-Ferrero, I.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M.; Muñoz-Torres, M.J. Rating the Raters: Evaluating how ESG Rating Agencies Integrate Sustainability Principles. Sustainability 2019, 11, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leins, S. ‘Responsible investment’: ESG and the post-crisis ethical order. Econ. Soc. 2020, 49, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokuwaduge, C.S.D.S.; Heenetigala, K. Integrating Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosure for a Sustainable Development: An Australian Study. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeyda, R.; Darmansya, A. The Influence of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure on Firm Financial Performance. IPTEK J. Proc. Ser. 2019, 5, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Nozawa, W.; Yagi, M.; Fujii, H.; Managi, S. Do environmental, social, and governance activities improve corporate financial performance? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Scores and Financial Performance of Multilatinas: Moderating Effects of Geographic International Diversification and Financial Slack. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, R. On the Nature of Managerial Tasks and Skills: Their Distinguishing Characteristics and Organization. In Managerial Work; Routledge: Manchester, UK, 2019; pp. 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, S.V.A.; Taylor, S.N. The influence of emotional and social competencies on the performance of Peruvian refinery staff. Cross Cult. Manag. 2012, 19, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waggoner, D.P. The use of political skill in organizational change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, A.C.V.; Stefano, S.R.; Munck, L. Competências voltadas à sustentabilidade organizacional: Um estudo de caso em uma indústria exportadora. Ges. Reg. 2015, 31, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kleef, J.A.; Roome, N.J. Developing capabilities and competence for sustainable business management as innovation: A research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.H. Knowledge, skills and organizational capabilities for structural transformation. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2019, 48, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Nielsen, A.P.; Bogner, W.C. Corporate entrepreneurship, knowledge, and competence development. Ent. Theory Pract. 1999, 23, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow-Howell, N.; Greenfield, J.C. Productive engagement of older Americans. China J. Soc. Work 2010, 3, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, C.A.P.; Pimentel, L.B.; Lattanzi, I.E. Organizational skills development: The context of information technologies. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 15, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschang, T. The Basic Characteristics of Skills and Organizational Capabilities in the Indian Software Industry; ADBI Research Paper Series; Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI): Tokyo, Japan, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; Koen, C.I.; Noorderhaven, N.G. Organizational Culture and Relationship Skills. Organ. Stud. 2006, 27, 833–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Lenssen, G.; Hind, P. Leadership Qualities and Management Competencies for Corporate Responsibility; The Academy of Business in Society: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zaccaro, S.J. Organizational leadership and social intelligence. In Multiple Intelligences and Leadership; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2002; pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, T.V.; Campion, M.A.; Morgeson, F.P. The leadership skills strataplex: Leadership skill requirements across organizational levels. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, L.; Yao, S. The Determinants Of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence From China. J. Appl. Bus. Res. (JABR) 2013, 29, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzma, E.L.; Doliveira, S.L.D.; Silva, A.Q. Competencias para la sostenibilidad organizacional: Una revisión sistemática. Cadernos EBAPE.BR 2017, 15, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- de Oliveira, A.C.; Sokulski, C.C.; da Silva Batista, A.A.; de Francisco, A.C. Competencies for sustainability: A proposed method for the analysis of their interrelationships. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 14, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Xia, E.; Ren, P. Organizational innovation based on core competence—Virtual enterprises. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Management of Innovation and Technology (ISMOT’04), Hanzhou, China, 24–26 October 2004; pp. 418–422. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, R. The Innovator's Dilemma as a Problem of Organizational Competence. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2006, 23, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekionea, J.P.B.; Plaisent, M.; Bernard, P. Developing Knowledge Management Competences as an Organizational Capability for Business Performance. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Knowledge Management (ECKM2007), Barcelona, Spain, 6–7 September 2007; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, G. Organizational competence for harnessing IT: A case study. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, P.M.; Sousa, R.D. The organizational competences model: A contribution for business-IT alignment. In Proceedings of the 17th International-Business-Information-Management-Association Conference. Creating Global Competitive Economies: A 360-Degree Approach, Milan, Italy, 14–15 November 2011; pp. 2140–2145. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Geng, X.; Yang, J. Identifying Organizational Knowledge Innovation for Technology Competence Growth of Enterprises. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Complex Science Management and Education Science (CSMES), Kunming, China, 23–24 November 2013; pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Bi, G.; Liu, H.; Fang, Y.; Hua, Z. Understanding employee competence, operational IS alignment, and organizational agility–An ambidexterity perspective. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.C.; Wang, Z.M. Market knowledge competence and organizational innovation performance: An empirical study in China. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Management Science and Engineering, Marrickville, Australia, 1 October 2005; pp. 1521–1525. [Google Scholar]

- Obukhova, L.A.; Galustyan, O.V.; Baklanov, I.O.; Belyaev, R.V.; Kolosova, L.A.; Dubovitskaya, T. Formation of Organizational Competence of Future Engineers By Means of Blended Learning. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2020, 10, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, C.M. Patterns Of Organizational Success: Leadership Competence, Organizational Knowledge Sharing, and Customer/Market Focus. Competencies and Professionalism. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management, Yokohama, Japan, 22–23 November 2008; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- De Sordi, J.O.; Azevedo, M.C. Analyses of Individual and Organizational Competences Associated with Knowledge Management Practice. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2008, 10, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danneels, E. Organizational antecedents of second-order competences. Strat. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 519–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladova, K. Dynamic Capablities and the Development of Organizational Competences. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Management and Industrial Engineering, Bucharest, Romania, 22–23 October 2015; Niculescu Publishing House: Bucarest, Romênia; pp. 573–579. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.; Guo, Y. Research on the relationships among knowledge transfer, organizational learning and dynamic competence. In Proceedings of the Ninth Wuhan International Conference on E-Business, Wuhan, China, 29 May 2010; pp. 1449–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; He, P. An empirical study on interaction among organizational learning, organizational innovation and corporate core competence. Proc. 3rd Int. Conf. Risk Manag. Glob. e-Bus. 2009, 1, 516–522. [Google Scholar]

- Zangiski, M.A.D.S.G.; de Lima, E.P.; da Costa, S.E.G. Organizational competence building and development: Contributions to operations management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 144, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, E.G.; Kim, A. Organizational structure, leadership and readiness for change and the implementation of organizational cultural competence in addiction health services. Eval. Program Plan. 2013, 40, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, D.J.; Beckwith, S.K. Organizational Barriers to Cultural Competence in Hospice. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2015, 32, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakeh, A. Competence Relationship with Organizational Excellence JKKK in Kuala Nerus, Terengganu. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Social and Political Development (ICOSOP 2016), Medan, Indonesia, 21–22 November 2016; Volume 81, pp. 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vasconcellos, S.L.; Garrido, I.L.; Parente, R.C. Organizational creativity as a crucial resource for building international business competence. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Varona, J.M.; Acebes, F.; Poza, D.; López-Paredes, A. Fostering Digital Growth in SMEs: Organizational Competence for Digital Transformation. In Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Moon, T. Impact of Digital Strategic Orientation on Organizational Performance through Digital Competence. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, R.N.; Kovaleski, J.; Resende, L.M. Methodi Ordinatio: A proposed methodology to select and rank relevant scientific papers encompassing the impact factor, number of citation, and year of publication. Scientometrics 2015, 105, 2109–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, R.N.; Kovaleski, J.L.; Resende, L.M. TICs na composição da Methodi Ordinatio: Construção de portfólio bibliográfico sobre Modelos de Transferência de Tecnologia. Ciência da Inf. 2017, 46, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes da Silva, M.; Abbade da Silva, R.; Arruda Coronel, D.; Marion Filho, P.J. The Brazilian Industrial Sector: Challenges and opportunities. Econ. Devel. Mag. 2019, 2, 28–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo; Edições: Lisboa, Portugal, 1977; 70p. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, L. ESG integration: Value, growth and momentum. J. Asset Manag. 2020, 21, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potocan, V. Technology and Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endovitsky, D.; Nikitina, L.; Borzakov, D. Corporate social responsibility: Comprehensive analysis. LAPLAGE EM Rev. 2021, 7, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.; Mota, F. Coordinated Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Ind. Competition Trade 2020, 20, 617–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, S.; Dai, N.; Belal, A.; Li, T.; Tang, G. Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Political, social and corporate influences. Account. Bus. Res. 2021, 51, 36–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Vázquez-Burguete, J.L.; García-Miguélez, M.P.; Lanero-Carrizo, A. Internal corporate social responsibility for sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, P. Human Services as Service Industries. Serv. Ind. J. 1996, 16, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensma, H.K. Acquiring technological competencies through inter-organizational collaboration: An organizational learning perspective. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 1996, 12, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rojas, R.; Fernández-Pérez, V.; García-Sánchez, E. Encouraging organizational performance through the influence of technological distinctive competencies on components of corporate entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 397–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.; Desha, C.; Baumeister, D. Learning from nature—Biomimicry innovation to support infrastructure sustainability and resilience. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 161, 120287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fetscherin, M.; Alon, I.; Lattemann, C.; Yeh, K. Corporate social responsibility in emerging markets: The importance of the governance environment. Manag. Int. Rev. 2010, 50, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic-Lazarevic, S. Good corporate citizenship in the Australian construction industry. Corp. Governance: Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2010, 10, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, Y.; Deegan, C. Corporate Social and Environment-related Governance Disclosure Practices in the Textile and Garment Industry: Evidence from a Developing Country. Aust. Account. Rev. 2013, 23, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmohammadi, C. Impact of corporate social responsibility practices on organizational performance: An ISO 26000 perspective. Soc. Responsib. J. 2014, 10, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches Garcíia, A.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Orsato, R.J. Sensitive industries produce better ESG performance: Evidence from emerging markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, M.A.; Butt, S.A. Financial and non-financial determinants of corporate social responsibility: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 780–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, R.G.G.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Nascimento, D.L.D.M.; Anholon, R.; Filho, W.L. Measurement of sustainability performance in Brazilian organizations. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadaoui, K.; Soobaroyen, T. An analysis of the methodologies adopted by CSR rating agencies. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2017, 9, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Nevárez, V.; Zavala Féliz, B.D. Social responsibility in the dimensions of corporate citizenship. A case study in agricultural manufacturing. Rev. Eco. Púb. Soc. Coop. 2019, 97, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehralian, G.; Zarei, L.; Akhgari, M.; Peikanpour, M. Does CSR matter in the pharmaceutical distribution industry? The balanced scorecard perspective. Int. J. Pharm. Health Mark. 2019, 13, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hamilton, T. What is driving corporate social and environmental responsibility in China? An evaluation of legacy effects, organizational characteristics, and transnational pressures. Geoforum 2020, 110, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Qin, H.; Gan, Q.; Su, J. Internal Control Quality, Enterprise Environmental Protection Investment and Finance Performance: An Empirical Study of China’s A-Share Heavy Pollution Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibrell, C.; Craig, J.B.; Kim, J.; Johnson, A.J. Establishing How Natural Environmental Competency, Organizational Social Consciousness, and Innovativeness Relate. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Masrek, M.N.; Nadzar, F.M. Analysis of competencies, job satisfaction and organizational commitment as indicators of job performance: A conceptual framework. Educ. Inf. 2015, 31, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deni, A.; Priansa, D.J.; Darmo, I.S.; Saribanon, E.; Riswanto, A.; Sumaryadi, S.; Ramdan, A.M. Organizational competency and innovation capability: The influence of knowledge management on business performance. Calitatea 2020, 21, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Asree, S.; Zain, M.; Razalli, M.R. Influence of leadership competency and organizational culture on responsiveness and performance of firms. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Gilmartin, M.; Sengul, M.; Pache, A.-C.; Alexander, J.A. Leadership competencies for implementing planned organizational change. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorenak, M.; Ferjan, M. The influence of organizational values on competencies of managers. Bus. Adm. Manag. 2015, 18, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mittal, S. Analysis of drivers of CSR practices’ implementation among family firms in India: A stakeholder’s perspective. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 27, 947–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, M.F.; Lenka, U. Organizational learning and Gen Y employees’ affective commitment: The mediating role of competency development and moderating role of strategic leadership. J. Manag. Organ. 2020, 26, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapolan, A.; Montanari, F.; Bonesso, S.; Gerli, F.; Mizzau, L. Behavioural competencies and organizational performance in Italian performing arts: An exploratory study. Acad. Rev. Latin. Adm. 2017, 30, 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munck, L.; Galleli, B.; De Souza, R.B. Delivery Levels of Support Competencies to Organizational Eco-efficiency: A case study in an electro-electronics sector industry. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2012, 14, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shet, S.V.; Patil, S.V.; Chandawarkar, M.R. Competency based superior performance and organizational effectiveness. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 753–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firooz, A. Investigate and explain the relationship between human resource competency dimensions with organizational performance. Life Sci. J. 2012, 9, 673–678. [Google Scholar]

- Long, C.S.; Ismail, W.K.W.; Amin, S.M. The role of change agent as mediator in the relationship between HR competencies and organizational performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2019–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulei, C.; Long, Y.; Ming, G. From career competency to skilled employees’career success in china: The moderating effects of perceived organizational support. Pak. J. Stat. 2014, 30, 737–750. [Google Scholar]

- Potnuru, R.K.G.; Sahoo, C.K. HRD interventions, employee competencies and organizational effectiveness: An empirical study. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2016, 40, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delicado, B.A.; Salado, A.; Mompó, R. Conceptualization of a T-Shaped engineering competency model in collaborative organizational settings: Problem and status in the Spanish aircraft industry. Syst. Eng. 2018, 21, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoo, F.N.K. Human resource management (HRM) practices and organizational performance: The mediating role of employee competencies. Empl. Relations 2019, 41, 949–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetisyan, E.; Hockerts, K. The Consolidation of the ESG Rating Industry as an Enactment of Institutional Retrogression. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.M. Environment, social, and governance (ESG) criteria and preference of managers. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1340820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Sharma, D. Do environment, social and governance performance impact credit ratings: A study from India. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2019, 35, 466–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, G.H.; Firoiu, D.; Pirvu, R.; Vilag, R.D. The Impact of Esg Factors on Market Value of Companies from Travel and Tourism Industry. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2019, 25, 820–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, F.; Migliavacca, M. The Determinants of ESG Rating in the Financial Industry: The Same Old Story or a Different Tale? Sustainability 2020, 12, 6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, R.; Alsayegh, M.F. Determinants of Corporate Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) Reporting among Asian Firms. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramba, M.; Joseph, C.; Said, R. Determinants of environment, social and governance disclosures by top Malaysian companies. Middle East J. Manag. 2021, 8, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C.; Pearce, J.A., II; Oghazi, P. Not so myopic: Investors lowering short-term growth expectations under high industry ESG-sales-related dynamism and predictability. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, R.K. Identifying and Integrating Individual Level and Organizational Level Core Competencies. J. Bus. Psychol. 1999, 14, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Karande, K.; Zhou, D. The effect of the governance environment on marketing channel behaviors: The diamond industries in the US, China, and Hong Kong. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primmer, E.; Wolf, S.A. Empirical Accounting of Adaptation to Environmental Change: Organizational Competencies and Biodiversity in Finnish Forest Management. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgeman, R.L.; Williams, J.A. Enterprise self-assessment analytics for sustainability, resilience and robustness. TQM J. 2014, 26, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh Salmasi, M.; Talebpour, A.; Homayounvala, E. Identification and classification of organizational level competencies for BI success. J. Intell. Stud. Bus. 2016, 6, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, C.C.; Kelley, D.C. What individual and organizational competencies facilitate effective collaboration? Findings from a collaborative governance simulation. J. Public Aff. Educ. 2018, 24, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, S. The risk-based approach to water management, and major challenges in the mining industry-ESG and the economics and ethics. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2020, 120, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ma, F. Development and Validation of an Organizational Competency Scale (OCS) for Elder Civic Engagement Programs: A Pilot Study. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2018, 46, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.W.; Fowler, S.W.; Zeithaml, C.P. Managing organizational competencies for competitive advantage: The middle-management edge. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2001, 15, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeijn, J.H.; Van Der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Van Der Lee, A. Multisource Ratings Of Managerial Competencies And Their Predictive Value For Managerial And Organizational Effectiveness. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verle, K.; Markič, M.; Kodrič, B.; Zoran, A.G. Managerial competencies and organizational structures. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depra, V.M.; Pereira, D.G.; De Marchi, A. The contribution of informal organizational learning to the development of managerial competencies. Navus–Rev. Gest. Tecnol. 2018, 8, 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kansal, J.; Jain, N. Development of competency model and mapping of employees competencies for organizational development: A new approach. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2019, 78, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, R.R.; de Mesquita, J.M.C.; de Mendonça, L.C. Taxonomy of comprehensive strategies and organizational competencies as influences of performance: Analysis in the sector of jewels, semi jewels and imitation jewelry. Rev. Elet. Estr. Neg. REEN 2019, 12, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Tovar, H.; Lara Figueroa, D.C. Identification of managerial competencies of the organizational leaders of the Passifloraceae production sector in the Huila Department. Cuad. Adm. 2020, 36, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Marqués, D.; García, M.G.; Sánchez, M.M.; Mari, M.P. Social entrepreneurship and organizational performance: A study of the mediating role of distinctive competencies in marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paajanen, P.; Porkka, P.; Paukku, H.; Vanharanta, H. Development of personal and organizational competencies in a technology company. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2009, 19, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Espallardo, M.; Rodríguez-Orejuela, A.; Sánchez-Pérez, M. Inter-organizational governance, learning and performance in supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2010, 15, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.W. Understanding creativity competency for organizational learning: A study of employees’ assumptions on creativity competency in creative industry. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 1198–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potnuru, R.K.G.; Sahoo, C.K.; Sharma, R. Team building, employee empowerment and employee competencies: Moderating role of organizational learning culture. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2019, 43, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolívar-Ramos, M.T.; García-Morales, V.J.; García-Sánchez, E. Technological distinctive competencies and organizational learning: Effects on organizational innovation to improve firm performance. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2012, 29, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitri, H.; Nugraha, A.T.; Hakimah, Y.; Manihuruk, C. Strategic Management of Organizational Knowledge and Competency Through Intellectual Capital. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 19, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Quirós, M.M.; Miralles-Quirós, J.L.; Redondo-Hernández, J. ESG Performance and Shareholder Value Creation in the Banking Industry: International Differences. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosemore, M.; Osborne, J.; Higgon, D. Affective, cognitive, behavioural and situational outcomes of social procurement: A case study of social value creation in a major facilities management firm. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2021, 39, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippins, M.J.; Sohi, R.S. IT competency and firm performance: Is organizational learning a missing link? Strat. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, A.; Grewal, R.; Sambamurthy, V. Information Technology Competencies, Organizational Agility, and Firm Performance: Enabling and Facilitating Roles. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 976–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Green, P. On Information Technology Competencies for Collaborative Organizational Structures. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 38, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Fernández-Valero, G.; Blanco-Callejo, M. Supplier Qualification Sub-Process from a Sustained Perspective: Generation of Dynamic Capabilities. Sustainability 2017, 9, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, N.; Balaji, M. Organisational sustainability scale-measuring employees’ perception on sustainability of organisation. Meas. Bus. Excel. 2021, 26, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).