Main Agro-Ecological Structure: An Index for Evaluating Agro-Biodiversity in Agro-Ecosystems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Indicators Selection

3. Development of MAS as Agro-Biodiversity Index

3.1. Connection with the Main Ecological Structure of the Landscape (CMESL)

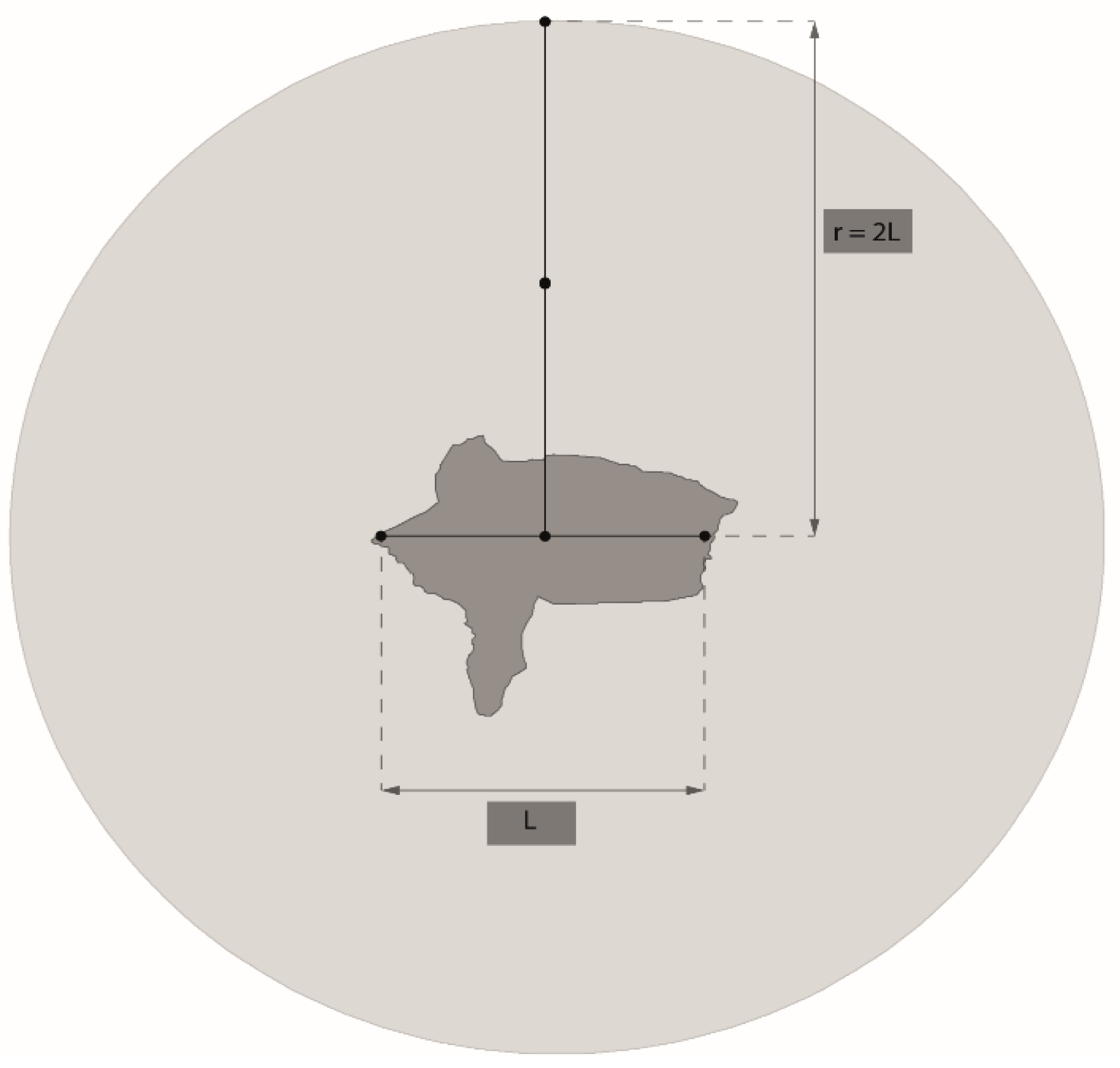

Establishment of Area of Influence in High Quality Matrixes (AI)

3.2. Extension of External Connectors (EEC)

3.3. Diversity of External Connectors (DEC)

3.4. Extension of Internal Connectors (EIC)

3.5. Diversity of Internal Connectors (DIC)

3.6. Land Use (LU)

3.7. Management Practices (PM)

3.7.1. Agriculture Management Practices (aMP)

3.7.2. Livestock Management Practices (lMP)

3.8. Conservation Practices (CP)

3.9. Perception, Awareness and Knowledge (PAK)

3.10. Action Capacity (AC)

4. Discussion

- Understand each of the indicators (and their variables) and identify their importance according to the objectives of the specific study. Understanding the cause would permit the elimination of certain related variables that overcomplicate the indicator but do not compromise the intention.

- Add, in a weighted manner, the indicators built with the same unit of measurement, within the criteria, as was proposed for the aggregation of criteria in the index (see Equation 23). It is also desirable to combine complementary methodologies to “emphasize” the importance of the indicators that may “hide” behind the final evaluation of the index. Quantitative methods such as the AMOEBA diagrams [102] and qualitative methods such as Design Structure Matrix (DSM) [103] permit visualizing the state of the different indicators in the evaluation scale constructed and in those that structure the system called MAS. Multivariate tests can be another alternative for interpreting the importance of certain indicators compared to others such as principal component analysis (PCA) [104] that collect variability in a few dimensions or main components, reflecting which indicators most contribute to this conformation and to selecting the model according to its adjustment.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Biodiversity for food and agriculture. In Contributing to Food Security in a Changing Word; FAO-PAR: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- SCDB. La Biodiversidad y la Agricultura. In Salvaguardando la Biodiversidad y Asegurando Alimentación para el Mundo; PNUMA: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2008; Volume 3, ISBN 9292251112. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.Á. Agroecología. In Bases Científicas para una Agricultura Sustentable; Nordan Comunidad: Montevideo, Uruguay, 1999; ISBN 9781624176531. [Google Scholar]

- Isbell, F.; Adler, P.R.; Eisenhauer, N.; Fornara, D.; Kimmel, K.; Kremen, C.; Letourneau, D.K.; Liebman, M.; Polley, H.W.; Quijas, S.; et al. Benefits of increasing plant diversity in sustainable agroecosystems. J. Ecol. 2017, 105, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliessman, S. Agroecology and agroecosystems. In Agroecosystems Analysis; Gliessman-Stephen, R., Ed.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 2004; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, C.A.; Grove, T.L.; Harwood, R.R.; Pierce Colfer, C.J. The role of agroecology and integrated farming systems in agricultural sustainability. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1993, 46, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, B.; Gauchan, D.; Joshi, B.K.; Chaudhary, P. Agrobiodiversity index to measure agricultural biodiversity for effectively managing it. In Proceedings of the 2nd National Workshop on CUAPGR, Kathmandu, Nepal, 22–23 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- de Boef, W.S.; Thijssen, M.H.; Shrestha, P.; Subedi, A.; Feyissa, R.; Gezu, G.; Canci, A.; da Fonseca Ferreira, M.A.J.; Dias, T.; Swain, S.; et al. Moving Beyond the Dilemma: Practices that Contribute to the On-Farm Management of Agrobiodiversity. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 788–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, Á.; Lores, A. Nuevos Índices para Evaluar la Agrobiodiversidad. Agroecología 2012, 7, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva, Á.; Lores, A. Assessing agroecosystem sustainability in Cuba: A new agrobiodiversity index. Elementa 2018, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, L.L.; Matienzo, Y.; Griffon, D. Diagnóstico participativo de la biodiversidad en fincas en transición agroecológica. Fitosanidad 2014, 18, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- León-Sicard, T.E. La Estructura Agroecológica Principal de los agroecosistemas. In Perspectivas Teórico-Prácticas; Primera; Instituto de Estudios Ambientales (IDEA), Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021; ISBN 9789587946055. [Google Scholar]

- León-Sicard, T.E.; Calderón, J.T.; Martínez-Bernal, L.F.; Cleves-Leguízamo, J.A. The Main Agroecological Structure (MAS) of the agroecosystems: Concept, methodology and applications. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Sicard, T.E. Agroecología: Desafíos de una ciencia ambiental en construcción. In Vertientes del Pensamiento Agroecológico: Fundamentos y Aplicaciones; Altieri, M., León-Sicard, T., Eds.; Sociedad Latinoamericana de Agroecología: Medellín, Colombia, 2010; pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- León-Sicard, T.E. Perspectiva Ambiental de la Agroecología. La Ciencia de Los Agroecosistemas; IDEAS-UNAL: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014; ISBN 9789587750843. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig, L. Ecological responses to habitat fragmentation per Se. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017, 48, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.B.; Danielson, B.J.; Pulliam, H.R. Ecological populations affect processes that in complex landscapes. Nord. Soc. Oikos 1992, 65, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, C.; Joannon, A.; Aviron, S.; Burel, F.; Meynard, J.M.; Baudry, J. The cropping systems mosaic: How does the hidden heterogeneity of agricultural landscapes drive arthropod populations? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 166, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, J.M.; Sebastián-González, E.; Alexander, K.L.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Botella, F. Effect of landscape configuration and habitat quality on the community structure of waterbirds using a man-made habitat. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2014, 60, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscharntke, T.; Klein, A.M.; Kruess, A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Thies, C. Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity. Ecosystem service management. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 857–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin-Kramer, R.; O’Rourke, M.E.; Blitzer, E.J.; Kremen, C. A meta-analysis of crop pest and natural enemy response to landscape complexity. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thies, C.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Tscharntke, T. Effects of landscape context on herbivory and parasitism at different spatial scales. Oikos 2003, 101, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchfield, E.K.; Nelson, K.S.; Spangler, K. The impact of agricultural landscape diversification on U.S. crop production. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 285, 106615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, T.; Moloney, K.A.; Naves, J.; Knauer, F. Finding the missing link between landscape structure and population dynamics: A spatially explicit perspective. Am. Nat. 1999, 154, 605–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A. Measuring Biologcial Diversity; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-632-05633-0. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, R.H. Gradient analysis of vegetation. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1967, 42, 207–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuatrecasas, J. Aspectos de la vegetación natural en Colombia. Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. Exac. 1958, 10, 221–268. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig, L.; Merriam, G. Habitat patch connectivity and population survival. Ecology 1985, 66, 1762–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letourneau, K.D.; Armbrecht, I.; Rivera, S.B.; Lerma, M.J.; Jíménez-Carmona, E.; Daza, C.M.; Escobar, S.; Galindo, V.; Gutierrez, C.; Lopez, D.S.; et al. Does plant diversity benefit agroecosystems? A synthetic review. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, L.A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Kremen, C.; Morales, J.M.; Bommarco, R.; Cunningham, S.A.; Carvalheiro, L.G.; Chacoff, N.P.; Dudenhöffer, J.H.; Greenleaf, S.S.; et al. Stability of pollination services decreases with isolation from natural areas despite honey bee visits. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gerth, A.; van Rossum, F.; Triest, L. Do liner landscape elements in farmaland act as biological corridors for polen disersal? J. Ecol. 2010, 98, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilken, G.C. Microclimate management by traditional farmers. Geogr. Rev. 1972, 62, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabhan, G.P.; Sheridan, T.E. Living fencerows of the Rio San Miguel, Sonora, Mexico: Traditional technology for floodplain management. Hum. Ecol. 1977, 5, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Dahlgren, R.A. A Review of vegetated buffers and a meta-analysis of their mitigation efficacy in reducing nonpoint source pollution. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgueitio, E.; Cuartas, C.; Naranjo, J. Ganadería del Futuro: Investigación para el Desarrollo, 2nd ed.; Fundación CIPAV: Cali, Colombia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bennet, A. Linkages in the Landscape: The Role of Corridors and Connectivity in Wildlife Conservation; UICN Series; Page Bros Ltd.: Norwich, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Quintero, I.; Daza-Cruz, Y.X.; León-Sicard, T.E. Connecting farms and landscapes through agrobiodiversity: The use of drones in mapping the Main Agroecological Structure. In Drones and Geographical Information Technologies in Agroecology and Organic Farming; DeMarchi, M., Pappalardo, S., Diantini, A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonney, R.; Cooper, C.B.; Dickinson, J.; Kelling, S.; Phillips, T.; Rosenberg, K.V.; Shirk, J. Citizen science: A developing tool for expanding science knowledge and scientific literacy. Bioscience 2009, 59, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, J.C.; Andrade, C.; Machon, N.; Porcher, E. On the use of parataxonomy in biodiversity monitoring: A case study on wild flora. Biol. Conserv. Conserv. 2008, 17, 3485–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez, A.; Bocco, G. Cambio en el uso del suelo. Cons. Nac. Cienc. Tecnol. 2004, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.G.; Gardner, R.H. Landscape Ecology in Theory and Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuussaari, M.; Bommarco, R.; Heikkinen, R.K.; Helm, A.; Krauss, J.; Lindborg, R.; Öckinger, E.; Pärtel, M.; Pino, J.; Rodà, F.; et al. Extinction debt: A challenge for biodiversity conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrig, L.; Merriam, G. Conservation of fragmented populations. Conserv. Biol. 1994, 8, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, M.; Gómez-Restrepo. Métodos en investigación cualitativa: Triangulación. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2005, 34, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.Á.; Trujillo, J. The agroecology of corn production in Tlaxcala, Mexico. Hum. Ecol. 1987, 15, 189–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.Á.; Nicholls, C.I. Agroecología y diversidad genética en la agricultura campesina. LEISA Rev. Agroecol. 2019, 35, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rosales-González, M.; Cervera-Arce, G.; Benavides-Rosales, G.; Guardianes de las semillas del sur de Yucatán Conservación in situ de semillas de la milpa. Experiencia y propuesta para el cuidado del patrimonio biocultural maya. LEISA Rev. Agroecol. 2019, 35, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Amend, T.; Brown, J.; Kothari, A.; Phillips, A.; Stolton, S. Protected Landscapes and Agrobiodiversity Values; IUCN & GTZ; Kasparek Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 1, ISBN 9783925064487. [Google Scholar]

- Gauchan, D.; Joshi, B.K.; Sthapit, S.; Ghimire, K.; Gautam, S.; Poudel, K.; Sapkota, S.; Neupane, S.; Sthapit, B.; Vernooy, R. Post-disaster revival of the local seed system and climate change adaptation: A case study of earthquake affected mountain regions of nepal. Indian J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2016, 29, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, N.; Carrillo-García, A.; Moeller, C.; Trethowan, R.; Sayre, K.D.; Govaerts, B. Conservation agriculture for wheat-based cropping systems under gravity irrigation: Increasing resilience through improved soil quality. Plant Soil 2011, 340, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, N.; François, I.; Govaerts, B. Agricultura de Conservación, ¿Mejora la Calidad del Suelo a fin de Obtener Sistemas de Producción Sustentables; Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo (CIMMYT): Mexico City, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Palm, C.; Blanco-Canqui, H.; DeClerck, F.; Gatere, L.; Grace, P. Conservation agriculture and ecosystem services: An overview. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 187, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, J.L.; Quemada, M.; Martín-Lammerding, D.; Vanclooster, M. Assessing the cover crop effect on soil hydraulic properties by inverse modelling in a 10-year field trial. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 222, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Valdes, Y. El Rol de las arvenses como componente en la biodiversidad de los agroecosistemas. Cultiv. Trop. 2016, 37, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Moreno, A.; Rivera, J. Rotación de cultivos intercalados de café, con manejo integrado de arvenes. Av. Técnicos Cenicafé 2003, 307. Available online: https://biblioteca.cenicafe.org/bitstream/10778/4184/1/avt0307.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Pautasso, M.; Aistara, G.; Barnaud, A.; Caillon, S.; Clouvel, P.; Coomes, O.T.; Delêtre, M.; Demeulenaere, E.; De Santis, P.; Döring, T.; et al. Seed exchange networks for agrobiodiversity conservation. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavijo, N.; Sánchez, H. Agroecología, seguridad y soberanía alimentaria. El caso de los agricultores familiares de Tibasosa, Turmequé y Ventaquemada en Boyacá. In La Agroecología. Experiencias Comunitarias para la Agricultura Familiar en Colombia; Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios-UNIMINUTO: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019; pp. 35–58. ISBN 9789587842326. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, A.; Acevedo-Osorio, Á.; Báez, C. Importancia de la agrobiodiversidad y agregación de valor a productos agroecológicos en la asociación Apacra en Cajamarca, Tolima. In La Agroecología. Experiencias Comunitarias para la Agricultura Familiar en Colombia; Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios-UNIMINUTO: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019; pp. 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- LEAP. Principles for the assesment of livestock impacts on biodiversity. In Environmental Assessment and Performance Partnership; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015; ISBN 9789251095218. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, V.E.; Roldan, F.; Dick, R.P. Soil enzymatic activities and microbial biomass in an integrated agroforestry chronosequence compared to monoculture and a native forest of Colombia. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2010, 46, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Regenerative agriculture for food and climate. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 75, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaarst, M.; Padel, S.; Hovi, M.; Younie, D.; Sundrum, A. Sustaining animal health and food safety in European organic livestock farming. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 94, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijlstra, A.; Eijck, I.A.J.M. Animal health in organic livestock production systems: A review. NJAS-Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2006, 54, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancier, M.; Subrahmanyeswari, B.; Mukherjee, R.; Kumar, S. Organic livestock production: An emerging opportunity with new challenges for producers in tropical countries. OIE Rev. Sci. Technol. 2011, 30, 969–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, A. Metodología de investigación científica cualitativa. In Psicología: Tópicos de Actualidad; Quintana, A., Montgomery, W., Eds.; Universidad Mayor de San Marcos: Lima, Perú, 2006; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Bases de la Investigación Cualitativa. Técnicas y Procedimientos para Desarrollar Teoría Fundamentada; Universidad de Antioquia: Medellín, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nietschmann, B. The Interdependence of Biological and Cultural Diversity; Center of World Indigenous Studies: Kenmore, WA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, V.M.; Barrera, N. La Memoria Biocultural: La Importancia Ecológica de las Sabidurías Tradicionales; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, España, 2008; ISBN 9788498880014. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Guía de Buenas Prácticas para la Gestión y uso Sostenible de Los Suelos en Áreas Rurales; FAO: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018; ISBN 978-92-5-130425-9. [Google Scholar]

- Murgueitio, E. Impacto ambiental de la ganadería de leche en Colombia y alternativas de solución. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2003, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghian, S.; Rivera, J.M.; Gómez, M.E. Impacto de sistemas de ganadería sobre las características físicas, químicas y biológicas de suelos en los Andes de Colombia. In Agroforestería para la Producción Animal en Latinoamérica; FAO: Bogotá, Colombia, 2000; pp. 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle, P.; Spain, A. Soil Ecology; Kluwer Academic Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yong-Zhong, S.; Yu-Lin, L.; Jian-Yuan, C.; Wen-Zhi, S. Influences of continuous grazing and livestock exclusión on soil propierties in a degraded sandy grassland, Inner Mongolia, northern China. Catena 2005, 59, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megersa, G.; Abdulahi, J. Irrigation system in Israel: A review. Int. J. Water Resour. Environ. Eng. 2015, 7, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darshna, S.; Sangavi, T.; Mohan, S.; Soundharya, A.; Desikan, S. Smart irrigation system. J. Electron. Commun. Eng. 2015, 10, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Captación y Almacenamiento de Agua de Lluvia. Opciones Técnicas para la Agricultura Familiar en América Latina y el Caribe; FAO: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2013; ISBN 9789253075805. [Google Scholar]

- JICA. Guía técnica para cosechar el agua de lluvia. In Opciones Técnicas para la Agricultra Familiar en la Sierra; Japanesse International Cooperation Agency: Riobamba, Ecuador, 2015; ISBN 9780874216561. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, V.; Visetti, Y.M. Sens et temps de la Gestalt. Intellectica 1991, 28, 147–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Melgarejo, L.M. Sobre el concepto de percepción. Ateridades 1994, 4, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1984; ISBN 0674074416. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.Á.; Nicholls, C.I. Agroecología y resiliencia al cambio climatico. Agroecología 2013, 8, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. La Trama de la Vida, 3rd ed.; Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock, J.E. Hands up for the Gaia hypothesis. Nature 1990, 344, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, V.M. Ecología, Espiritualidad y Conocimiento -de la Sociedad del Riesgo a la Sociedad Sustentable; Primera; PNUMA Oficina Regional para América Latina y el Caribe, Universidad Iberoamericana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2003; ISBN 968791324X. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Barrientos, L.; Magaña-Magaña, M.; Aguilar-Jiménez, A.; Ricalde, M. Factores socioeconómicos asociados al aprovechamiento de la agrobiodiversidad de la milpa en Yucatán. Ecosistemas Recur. Agropecu. 2016, 3, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, G.; Ramírez, L. Uso, manejo y conservación de la arobiodiversidad por comunidades campesinas afroamericanas en el municipio de Nuquí, Colombia. Etnobiología 2015, 13, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Daza-Cruz, Y.X. Apropiación Humana de la Producción Primaria neta en Sistemas de Agricultura Ecológica y Convencional. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- León-Sicard, T.E. La dimensión simbólica de la agroecología. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Agrar. UNCuyo 2019, 51, 395–400. [Google Scholar]

- Kniivilä, M.; Saastamoinen, O. The opportunity costs of forest. Silva Fenn. 2002, 36, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leguia, D.; Moscoso, F. Análisis de Costos de Oportunidad y Potenciales Flujos de Ingresos por REDD+: Una Aproximación Eonómica-Espacial Aplicada al caso de Ecuador; Programa Nacional Conjunto ONU REDD+: Quito, Ecuador, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Zambrano, F.H. (Ed.) Herramientas de Manejo para la Conservación de Biodiversidad en Paisajes Rurales; Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt y Corporación Autónoma Regional de Cundinamarca (CAR): Bogotá, Colombia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Casado, G.; Alonso-Mielgo, A. La investigación participativa en agroecología: Una herramienta para el desarrollo sustentable. Ecosistemas 2007, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R. La agroecología como un modelo económico alternativo para la producción sostenible de alimentos. Rev. Arbitr. Orinoco Pensam. Prax. 2013, 3, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- González de Molina, M.; García, D.; Casado, G. Politizando el consumo alimentario: Estrategias para avanzar en la transición agroecológica. Redes 2017, 22, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, C.I.; Henao, A.; Altieri, M.Á. Agroecología y el diseño de sistemas agrícolas resilientes al cambio climático. Agroecología 2015, 10, 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Torremocha, E. Sistemas Participativos de Garantía. Una Herramienta Clave para la Soberanía Alimentaria; Mundubat: Bilbao, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, D.I.Á.; Rodríguez, C.A.A. Construyendo desde la base una opción de vida: Experiencia de la Red de Mercados Agroecológicos Campesinos del Valle del Cauca-Redmac. In La Agroecología. Experiencias Comunitarias para la Agricultura Familiar en Colombia; Acevedo, A., Jiménez, N., Eds.; Universidad Minuto de Dios: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019; pp. 161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Prager, M.; Restrepo, J.; Ángel, D.; Malagón, R.; Zamorano, A. Agroecología. Una Disciplina para el Estudio y Desarrollo de Sistemas Sosteniblesde Producción Agropecuaria; Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Sede Palmira: Palmira, Colombia, 2002; ISBN 958-8095-14-X. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, F.F. Reseña sobre el estado actual de la agroecología en Cuba. Agroecology 2017, 12, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, A. Strengths and weaknesses of common sustainability development indices of multidimensional systems. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaver, E.; Beloff, E. Sustainability indicators and metrics of industrial performance. In Proceedings of the SPE International 60982, Stavanger, Norway, 26–28 June 2000; Society of Petroleum Engineers, Inc.: Dallas, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Brink, B.J.E.; Hosper, S.H.; Colin, F. A quantitative method for description and assessment of ecosystems: The amoeba-approach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1991, 23, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIT. Design Structure Matrix. Complex Systems Engineering Course. Available online: http://web.mit.edu/dsm (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Hill, M.O.; Gauch, H.G. Detrended Correspondence Analysis: An improved ordination technique. Vegetatio 1980, 42, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, J.; Gómez, D.; Nicholls, C. La estructura importa: Abejas visitantes de café y Estructura Agroecológica Principal (EAP) en cafetales. Rev. Colomb. Entomol. 2014, 40, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, R. Conceptos Básicos Sobre Agroecosistemas; Centro Agronómico de Investigación y Enseñanza (CATIE): Turrialba, Costa Rica, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The 10 Elements of Agroecology: Guiding the Transition to Sustainable Food and Agricultural System; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. FAO’s Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation (TAPE): Process of Development and Guidelines for Application: Test Version; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2019; ISBN 9789251320648. [Google Scholar]

- Legendre, P.; Borcard, D.; Peres-Neto, P. Analyzing beta diversity: Partitioning the spatial variation of community composition data. Ecol. Monogr. 2005, 75, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification Rr | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| 31 or more species. | 10 | |

| Between 21 and 30 species. | 8 | |

| Between 11 and 20 species. | 6 | |

| Between 5 and 10 species. | 3 | |

| With less than five species. | 1 | |

| Value | ||

|---|---|---|

| More than five vegetative strata. | 10 | |

| Four vegetative strata. | 8 | |

| Three vegetative strata. | 6 | |

| Two vegetative strata. | 3 | |

| Only one vegetative strata. | 1 | |

| Indicator | Description | Evaluation Categories | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seeds (SEe) | Type, production and conservation. | Own seed, ecological/ancestral, diverse and produced locally. Conserved through ecological practices. | 10 |

| Acquired seed, ecological/ancestral, diverse and obtained locally. Conserved through ecological practices. | 8 | ||

| Acquired seed, organic, diverse, and not obtained locally. Conserved through chemical procedures. | 6 | ||

| Conventional seed, not diverse (hybrids) and not obtained locally. Conserved by chemical procedures. | 3 | ||

| Transgenic seed. | 0 | ||

| Soil preparation (SoP) | Type of tillage, intensity, Use of conservation agriculture practices. | Zero plowing. Low intensity labor. Agricultural conservation practices: green fertilizer, coverage or mulch, harvest residue management, stubble and/or fallow. | 10 |

| Reduced tillage. Non intensive labor. With or without soil conservation practices. | 8 | ||

| Reduced tillage (chisel). Medium intense labor. Without soil conservation practices. | 6 | ||

| Conventional tillage (plows, rakes, dredges). Intensive labor. A soil conservation practice. | 3 | ||

| Conventional tillage. High intensity labor. Without soil conservation practices. | 0 | ||

| Fertilization (FEr) | Types of manure and fertilization, rotation, Complementary practices. | Organic fertilizers produced on farm: compost, manure, humus, green fertilizer, bio-fertilizers, microbe preparation, worm compound. High rotation. With complementary practices (use of mulch, fallow). | 10 |

| Purchased organic compounds. High rotation. With complementary practices. | 8 | ||

| Organic fertilizers mixed with chemical fertilizers. High to medium rotation. Few complementary practices. | 6 | ||

| Chemical fertilizers with low dosage. Little rotation. Some complementary practices. | 3 | ||

| High doses of chemical fertilizers. Without rotation. With no complementary practices. | 0 | ||

| Phytosanitary management (PyM) | Weeds management. Complementary practices. Biological, mechanical or chemical pest control. | Ecological handling of weeds. Use of complementary practices: bioles, slurry, hydrolates, push–pull systems, accompanying crops. Mechanical and biological controls are used. Pesticides are not used. | 10 |

| Ecological handling of weeds. Few complementary practices. Biological and mechanical controls. Pesticides are not used. | 8 | ||

| Ecological handling of weeds without complementary controls. Mechanical and biological controls. Application of recommended pesticides in low doses. | 6 | ||

| Manual weed eradication, some complementary practices, mechanical controls. Application of pesticides in recommended doses. | 3 | ||

| Chemical eradication of weeds. Elimination of habitats without complementary processes. Mechanical or biological controls. Application of pesticides in higher doses than the recommended. | 0 | ||

| Crop diversification (CrD) | Species and variety cultivated for human consumption. | More than 60 species, where at least two or more varieties of three species are cultivated (native and commercial). | 10 |

| 60 or more species where at least two or more varieties of two species are cultivated (native and commercial). | 8 | ||

| Between 30 and 60 species, with no native varieties. | 6 | ||

| Between 5 and 29 species, with no native varieties. | 3 | ||

| Less than 5 species, with no native varieties. | 0 |

| Indicator | Description | Evaluation Categories | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil preparation (SoP) | Type and intensity of tillage, manure, fertilizers or corrections, complementary practices | Zero tillage or very low intensity labor: direct planting. Use of corrections and organic matter. With complementary practices: forage associations with previous (potato, pea, corn, and/or bean) or accompanying crops, application of mycorrhiza, conservation of big trees and palms in the paddocks. | 10 |

| Minimum tillage or low intensity labor: planting in grooves, or vertical (use of light mechanization with furrows), mechanical or animal traction sowers. Use of corrections and organic fertilizer. With or without complementary practices. | 8 | ||

| Conventional tillage or medium intensity labor: sowing breaking up, loosening and chopping the ground (use of light mechanization or manually with a hoe). Low mineral or chemical fertilization, in lower doses than recommended. With or without complementary practices. | 6 | ||

| Conventional tillage or high intensity labor: mixed sowing or manually with hoe. Chopping and rechopping the soil (use of heavy machinery or manually with hoe). Medium or sporadic chemical fertilization according to recommendations. Without complementary practices. | 3 | ||

| Conventional tillage or very high intensity labor: sowing by deeply digging and turning over the soil (use of heavy machinery). Very high frequent or chemical fertilization, higher than recommended doses. With no complementary practices. | 0 | ||

| System arrangement (SiA) | Silvo-pasture system, diversity of grasses and legumes, dispersed trees, forage banks (Although live fences and windbreak curtains are mentioned in traditional evaluation of agroforestry type, they are not included in this table because their evaluation was already carried out in terms of internal and external connectors) | Intensive silvo-pasture system (iSPS) with several additional silvo-pasture systems in more than 75% of the farm’s productive area. High diversity of forage grasses (tussocks or stolonifers) and creeping legumes. Exist mixed forage banks. | 10 |

| iSPS and/or two additional silvo-pasture systems on less than 75% of the farm’s productive area. High diversity of forage grasses (two or more of tussock growth such as stolonifers). Trees and bushes (for different uses, including forage) high density dispersion (≥25 individuals ha−1). Two (2) additional forage matter exist. | 8 | ||

| Without iSPS or other silvo-pasture systems. Medium forage grass diversity. Combination of two forage grasses where growth type does not matter, low tree and bush density (<25 individuals ha−1) but in linear disposition. Additional forage (cutting grass) in combination with sugar cane, molasses, or other energizer. | 6 | ||

| Without iSPS or other silvo-pasture systems. Low forage grass diversity and low tree and bush density (<25 individuals ha−1). Only one forage grass species. No additional forage. Complemented with mineralized salts. | 3 | ||

| Without iSPS or other silvo-pasture systems. Very low diversity of forage grasses, without trees and bushes. Only one species of grass as monoculture. The trees have been removed from the pastures. Without forage banks. Not complemented by mineralized salts. | 0 | ||

| Pasture rotation (PaR) | Grazing system, time, measurements | Semi-stabled: The animals spend most of their time confined under a roof. Very short grazing periods (hours per day). | 10 |

| Highly rotational in strips or small pastures, isolation with electric fence. Short periods of stay (maximum between 1 to 2 days). Gauges are practiced. Pasture recovers quickly. | 8 | ||

| Moderate amount of rotation in medium-sized pastures, isolated by electric fence or live fence. Medium periods of occupation, between 3 and 7 days. Measurements are not carried out. The pasture is able to recover before the occupation cycle begins. | 6 | ||

| Little rotation in large pastures. Long occupation periods from 8–30 days, isolated or not by live or electric fences. Measurements are not carried out. The pasture is not able to recover until the following occupation period. | 3 | ||

| Being large in size, no pasture rotation. Occupation periods of more than 30 days. Measurements are not carried out. The pastures do not recover. | 0 | ||

| Water management (WaM) | Origin, transportation, use, storage, quality control for animal consumption. | Natural sources (sources, glens). Cattle aqueducts for circulation of treated and/or potable water. If there is irrigation, appropriate technologies are used. Frequent (by semester) physiochemical and bacteriological analysis. Total availability and potability. | 10 |

| Natural sources that supply the fixed water distribution system (pipes or hoses), with no leakage. If there is irrigation, appropriate technologies are used. Infrequent physiochemical and bacteriological analysis (yearly). Total availability and partial potability. | 8 | ||

| Artificial reservoirs (wells, water harvest, ponds, cisterns) that supply the water distribution system (hoses) with leaks. If there is irrigation, appropriate techniques are used. Infrequent phytochemical and bacteriological analysis (biannual) or none at all. Partial availability and partial potability. | 6 | ||

| Artificial reservoirs. Connection or transport through hoses, with leaks. If there is irrigation, appropriate technologies are used. Infrequent or non-existent phytochemical and bacteriological analysis. Partial availability and apparent partial potability. | 3 | ||

| Artificial reservoirs. Manual transport. No physical–chemical analysis. No guaranteed availability or potability. | 0 | ||

| Sanitary management (SaM) | Parasite control methods | Control of parasites (ecto and endo) is based on alternative veterinary medicine (food supplements with de-parasitized plants or immune stimulants, baths with repellent plants or minerals, homeopathy, acupuncture). Other complementary practices: preventive coprological exams, biological/natural control of flies and gastrointestinal parasites with dung beetles, co-phages, parasitoid wasps, entomo-pathogenic/anthelmintic fungus, or others. | 10 |

| Parasite control (ecto and endo) is based on the use of alternative veterinary medicine. There are no complementary practices. | 8 | ||

| Parasite control (ecto and endo) is based on the use of chemically synthesized anthelmintic medicines in less than recommended annual doses, and only in animals. | 6 | ||

| Chemical substances are used in recommended annual doses in all the herd. | 3 | ||

| Parasite control (ecto and endo) is only performed with anthelmintic, endectocide, and other synthetic drugs, in yearly doses superior to those recommended. | 0 |

| Indicator | Description | Evaluation Categories | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Conservation Practices (CsP) | Erosion control methods. Soil analysis. Use conflicts | Use of at least three erosion control methods, overgrazing control, slope protection, construction of terraces, carving or gabions. There is no soil use conflict. Carry out periodical soil analysis. | 10 |

| Use one or two methods of erosion control. Irrigation using appropriate technology. Carry out, or not, periodical soil analysis. Conflict over soil use exists on at least 25% of the farm area. | 8 | ||

| Use of at least one method of erosion control. No soil analysis. Conflict over soil use on a part of the farm (between 25 and 50% of the area). | 6 | ||

| No use of erosion control methods. No soil analysis. No use of erosion control methods. No soil analysis carried out. Irrigation using Inappropriate technologies. Conflict in soil use on most of the farm (between 50 and 75% of the area). | 3 | ||

| No use of erosion control methods. No soil analysis. Irrigation using Inappropriate technologies. Conflict in soil use in over 75% of the farm area. | 0 | ||

| Water Conservation Practices (CwP) | Protection of bodies of water. Water collection. Hydric balance. Spills | Sources, recharge sites and rounds of stream, ravines, rivers, and protected bodies of water with natural vegetation according to environmental regulations. Carries out water collection practice: water harvesting, recycling, deviation ditches, jagüeyes, wells, reservoirs, if necessary. Use hydraulic balances. No contaminating spills. | 10 |

| All water sources or springs protected by natural vegetation, without following environmental regulations. Some water collection practices when necessary. No contaminating spills. No hydraulic discharges. | 8 | ||

| Water source(s) or spring(s) are 50% or more protected by natural vegetation. Few water collection practices. No contamination of water spills. | 6 | ||

| The hydric source(s) or spring(s) are at least 50% totally protected by natural vegetation or barbed wire. Some complementary practices. Contaminating spills. | 3 | ||

| No protected spring. No complementary practices. Contaminating spills. | 0 | ||

| Biodiversity Conservation Practices (CbP) | Six of the following practices are found: reforestation with native species, management of other covers for natural recovery, intentional introduction of native or useful species (plants with flowers and fruit, plants—trap, medicinal and aromatic), habitat protection for various animals, germplasm banks. | 10 | |

| Evidence of 4 to 5 of the practices mentioned. | 8 | ||

| Evidence of 2 to 3 of the practices mentioned. | 6 | ||

| Evidence of at least 1 of the practices mentioned. | 3 | ||

| No use of biodiversity conservation practices. | 0 |

| Indicators | Description | Evaluation Categories | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perception and conscience (PeCo) | Perception—conscience: Level of understanding of the importance (I) of agro-biodiversity, conservation and of the benefits (B) that this offers Perception level depends on expressing both importance and benefits (I-B) and that the discourse accompanies or materializes in concrete actions in agro-ecosystem conservation and management | The farm owners or administrators express both the perceived importance and benefits from agro-biodiversity in agro-ecosystems, and this double character materializes in well-defined management and conservation actions. | 10 |

| The farm owners and/or administrators express both perceived importance and benefits received from agro-biodiversity in their agro-ecosystems, but they only materialize in actions in one of the two aspects. | 8 | ||

| The farm owners and/or administrators express the importance or benefits of biodiversity, but not an I-B relationship. There are no concrete actions in their agro-ecosystems to support their words. | 6 | ||

| The farm owners and/or administrators express the benefits but not the importance of agro-biodiversity. There are no concrete actions in their agro-ecosystems to support their words. | 3 | ||

| The farm owners and/or administrators do not express either the importance or the benefits they obtain in their agro-ecosystems. They show no interest in the topic. | 0 | ||

| (Kno) | Knowledge: degree of conceptual clarity regarding components of agro biodiversity and a notion of the underlying processes of structural connectivity of agro bio-diversity in order to potentiate their relations and functions in the productive system, acquired through academic or technical education, or learning from life (popular knowledge) | The owners and/or administrators are familiar with specific components of biodiversity (plants, animals, fungus, and other microorganisms) present on the farm, as well as uses, properties and other popular knowledge. They also know the role of vegetation connector methods to potentiate agro-biodiversity and the productive system. | 10 |

| The owners and/or administrators are familiar with certain specific components of bio-diversity (ex. plants, animals) but have very little notion of vegetation connectors or methods to potentiate the benefits of agro-biodiversity. | 8 | ||

| The owners and/or administrators are familiar with few components of biodiversity (Ex. plants) and have some knowledge of the role associated with vegetation connectors. They recognize certain methods, but not the benefits to their system. | 6 | ||

| The owners and/or administrators are familiar with few specific biodiversity components (Ex: plants) and have some related knowledge, but not of the role of vegetation connectors. They know of no method to potentiate the benefits of agro-biodiversity in their productive system. | 3 | ||

| The owners and/or administrators do not recognize any specific component of biodiversity or knowledge associated with the role vegetation connectors or of methods to potentiate biodiversity in their productive system. | 0 |

| Indicator | Description | Categories of Evaluation | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic and financial capacity (EfC) | Destination of financial resources for coverage conservation, and natural resource and agro-ecological processes A: Savings and personal resources AC: Access to credit AP: Access to institutional support programs (ASP, support from NGOs. Land tax exemption, among others) DA: Destination of areas with productive potential (agricultural or livestock systems) to conservation | A, AC and AP used as sources of financing in processes of coverage improvement and agro-ecological production. There is also the possibility of counting on the possibility of changing a productive use to a conservation use (DA). | 10 |

| Two of the three sources of financing directed toward coverage improvement and agro-ecological production exist. There is also the possibility of changing a productive use to a conservation use. (DA). | 8 | ||

| One of the three sources of financing directed toward coverage improvement processes and agro-ecological production are present. There is also the possibility of changing from a productive use to a conservation use (DA). | 6 | ||

| No external sources of financing are present, but there is the possibility of changing from a productive use to a conservation use (DA). | 3 | ||

| There are no external sources of financing or possibility of changing from a productive use to a conservation use (DA). | 0 | ||

| Logistic capacity (LoC) | Conditions of mobility, availability of qualified labor to work in strengthening of vegetal cover processes and agro-ecological/sustainable production AMT: Access to means of transportation FN: Nearby forest nurseries LA: Labor availability | There are good access roads, good access to means of transportation. There are nearby nurseries and readily available labor for strengthening vegetal cover and/or agricultural production. | 10 |

| Three logistic conditions required for strengthening vegetal coverage are present. | 8 | ||

| Two logistic conditions required for strengthening coverage are present. | 6 | ||

| One logistic condition required for strengthening coverage is present. | 3 | ||

| No logistic condition required for strengthening coverage are present. | 0 | ||

| Management capacity (MaC) | Farm management factors to improve and strengthen vegetal cover, promote agro-biodiversity and production and agro-ecological/sustainable marketing RI: Relations with institutions Associability or capacity to form alliances with the community PP: Shows planning of soil uses MC: markets for commercialization | The four management faction oriented toward maintaining vegetal cover and agro-ecological production are present. | 10 |

| Three management factors oriented toward maintaining vegetal cover and agro-ecological production are present. | 8 | ||

| Two management factors oriented toward maintaining vegetal cover and agro-ecological production are present. | 6 | ||

| One management factor oriented toward maintaining vegetal cover and agro-ecological production are present. | 3 | ||

| No management factor oriented toward maintaining vegetal cover and agro-ecological production is present. | 0 | ||

| Technological and Technical Capacity (TtC) | ATc: access to adequate/appropriate technology TA: technical assistance in ecological/sustainable agriculture or livestock, and conservation of natural resources CA: offer of training in topics of ecological/sustainable agriculture or livestock and conservation of natural resources | Access to appropriate or adequate technologies for field work. There is frequently an offer of technical assistance and the presence of development institutions oriented toward agro-biodiversity or ago-ecological production. | 10 |

| Access to appropriate or adequate technologies. There are infrequent offers of technical assistance. There are development institutions offering programs oriented toward agro-biodiversity or agro-ecological production. | 8 | ||

| There is no access to appropriate or adequate technologies. There are technical assistance offers. There are no programs oriented toward agro-biodiversity or agro-ecological production. | 6 | ||

| There is no access to appropriate or adequate technologies. There are offers of technical assistance although infrequent or not well directed. There are institutions that give infrequent support to agro-bio diversity or agro-ecological production programs. | 3 | ||

| There is no access to appropriate or adequate technologies; no offer of technical assistance. There are no institutions that promote programs oriented toward agro-biodiversity or agro-ecological production. | 0 |

| Numeric Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 91–100 | Completely developed in their agro-biodiversity. |

| 81–90 | Very strongly developed in their agro-biodiversity. |

| 71–80 | Strongly developed in their agro-biodiversity. |

| 61–70 | Moderate to strongly developed in their agro-biodiversity. |

| 51–60 | Moderately developed in their agro-biodiversity. |

| 41–50 | Slightly to moderately developed in their agro-biodiversity. |

| 31–40 | Slightly developed in their agro-biodiversity. |

| 21–30 | Weakly developed in their agro-biodiversity. |

| 11–20 | Very weakly developed in their agro-biodiversity. |

| <10 | With no structure or agro-biodiversity. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quintero, I.; Daza-Cruz, Y.X.; León-Sicard, T. Main Agro-Ecological Structure: An Index for Evaluating Agro-Biodiversity in Agro-Ecosystems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113738

Quintero I, Daza-Cruz YX, León-Sicard T. Main Agro-Ecological Structure: An Index for Evaluating Agro-Biodiversity in Agro-Ecosystems. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):13738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113738

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuintero, Ingrid, Yesica Xiomara Daza-Cruz, and Tomás León-Sicard. 2022. "Main Agro-Ecological Structure: An Index for Evaluating Agro-Biodiversity in Agro-Ecosystems" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 13738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113738

APA StyleQuintero, I., Daza-Cruz, Y. X., & León-Sicard, T. (2022). Main Agro-Ecological Structure: An Index for Evaluating Agro-Biodiversity in Agro-Ecosystems. Sustainability, 14(21), 13738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113738