Vitality Evaluation of Public Spaces in Historical and Cultural Blocks Based on Multi-Source Data, a Case Study of Suzhou Changmen

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Characteristics of Historical and Cultural Blocks

- Real historical relics have authentic historical relics and ensure a certain proportion; for instance, the cultural relics and historic buildings should cover an area of more than 60% of a historical and cultural block [3].

- Complete historical style and features: the style and features of the block are complete, which can reflect the characteristics of a specific historical period or the characteristics of a particular nationality and region, and has a certain scale of influence, which can be viewed as the history of the whole area.

- Cultural inheritance: historical and cultural blocks are the carriers of urban culture, such as clouding cultural traditions, lifestyles, customs, social structures, and so on, which gives the block special cultural values.

1.2. Status and Problems of Historical and Cultural Blocks in the Context of Stock Planning in China

2. Literature Review

2.1. Vitality of Urban Blocks

2.2. Vitality of Historical and Cultural Blocks in China

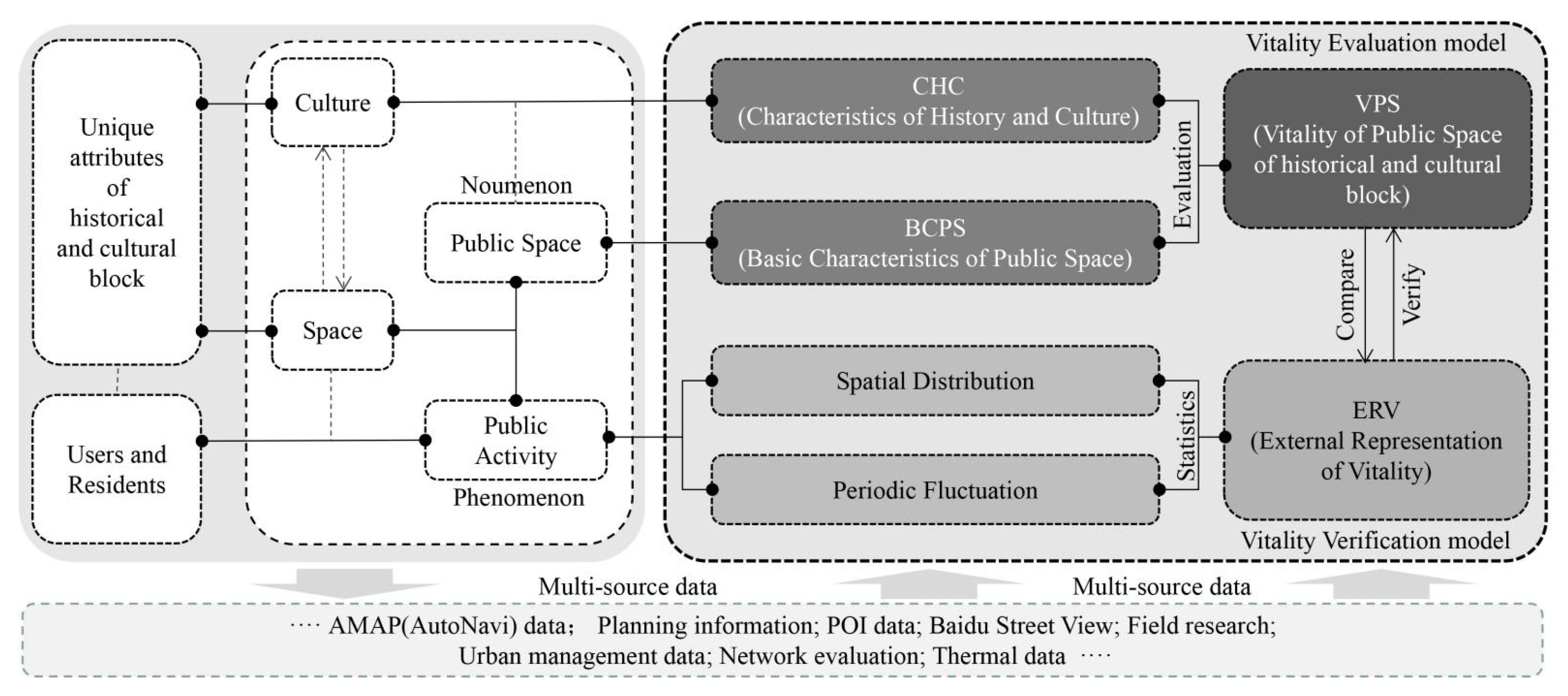

3. Vitality Evaluation Based on Multi-Source Data

3.1. Multi-Source Data

3.1.1. Multi-Dimensional Coverage

3.1.2. Cross-Correlation

3.1.3. Open Adaptability

3.2. Vitality Evaluation Model

3.2.1. Categories (Target Layer)

3.2.2. Indicators (Rule Layer)

3.2.3. Main Influence Factors (Index Layer)

3.2.4. Evaluation Criteria and Weight

3.3. Characterization and Evaluation Criteria

3.3.1. Accessibility

- Spatial Accessibility

- Traffic Convenience

3.3.2. Comfort

- Spatial Scale

- Green View Ratio

- Rest/Recreational Facilities

- Sanitary Facilities

3.3.3. Functionality

- Mixedness

- Density

- Impact

3.3.4. Characteristics of Material Elements

- Historical Value

- Authenticity

3.3.5. Characteristics of Non-Material Elements

4. Empirical Application: Evaluation of the Vitality of Public Space in Changmen Historical and Cultural Block

4.1. Sample Block Overview and Evaluation Unit

4.1.1. Sample Block

4.1.2. Evaluation Unit

4.2. Indicators of Vitality Evaluation of the Sample Block

4.2.1. Accessibility

4.2.2. Comfort

4.2.3. Functionality

4.2.4. Characteristics of Material Element

4.2.5. Characteristics of Non-Material Element

4.3. Comprehensive Evaluation and External Representation of Vitality

4.3.1. Comprehensive Evaluation of Vitality

4.3.2. External Representation of Vitality (Verification)

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion on the Correlation between Evaluation and Representation

5.2. Vitality Promotion Strategy Based on Evaluation

5.2.1. Improve Path According to the Basic Characteristics of Public Space

5.2.2. Improve Path According to the Characteristics of History and Culture

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.; Jia, Z. The enlightenment of “historical dynamics” to the space restoration of historical blocks. Archit. J. 2018, S1, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, H.; Sun, Y. Review on Historical District Preservation and Renovation Practice. Planners 2015, 31, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T50357-2018; Standard of Conservation Planning for Historic City. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Reid, E.; Otto, C. Measuring Urban Design: Metrics for Livable Places; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO World Heritage Center: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jane, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1961; pp. 56–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kevin, L. Good City Form; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ian, B. Urban Transformations: Power, People and Urban Design; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D. The Theory of City Form Vitality; South-East University Press: Nanjing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Wu, Q. Evaluation of urban vitality based on fuzzy object element model. Geogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 26, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, F. Coordinated develop-ment of historical inheri.tance and the city’s vitality. New Archit. 2016, 1, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, K. The New Urbanism: Towards an Architecture of Community; MC Raw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- John, M. Making a City: Urbanity, Vitality and Urban Design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Song, J. Identifying the Relationship between Urban Vitality and the 3D Characteristics of Built Environment: A Case Study of Wuhan, China. Mod. Urban Res. 2020, 8, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ta, N.; Zeng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, J. Relationship Between Built Environment and Urban Vitality in Shanghai Downtown Area Based on Big Data. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2020, 40, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Y. Preservation and Renewal: A Study on Visual Evaluation of Urban Historical and Cultural Street Landscape in Quanzhou. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L.; Yin, Z. Quantitative Evaluation on Street Vibrancy and Its Impact Factors: A Case Study of Chengdu. New Archit. 2016, 1, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, L.; Chen, Z. Vitality Upgrade for Historical and Cultural Blocks Based on Inhabitant Spatial Integration. Planners 2017, 33, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L. Functional and Spatial Revival in Historic Area from the Perspective of Raising Vitality. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Research for the Historic Area Conservation based on Development Vitality. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Feng, W.; Zhao, J. Quantitative Evaluation and Improvement Strategies Exploration of the Vigor of Residential Historical and Cultural Streets and Communities. Shanghai Urban Manag. 2017, 26, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Social Impact Assessment on The Conservation of Residential Historic Districts. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Research on Heritage Conservation based on Local Community in the Context of Inner-city Redevelopment: Case Study of Tianjin. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.; Ling, Q. Study on the Assessment of Street Vitality and Influencing Factors in the Historic District—A Case Study of Shichahai Historic District. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 35, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra de Oliveira, S.; Biancardo, S.A.; Tibaut, A. Optimizing H-BIM Workflow for Interventions on Historical Building Elements. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Nes, A.V. Quantitative tools in urban morphology: Combining space syntax, spacematrix and mixed-use index in a GIS framework. Urban Morphol. 2014, 18, 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Xi, Z. Strategies and Tectics of Integrating Water with City in the Urbanization of Jiangnan Region. In Proceedings of the 2017 UIA World Architects Congress, Seoul, Korea, 3–9 September 2017; Volume 9, pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Xi, Z. Research of the Evaluation Model of Urban External Space from the Perspective of Internet. In Proceedings of the 11th ISAIA Congress (The International Symposium on Architectural Interchanges in Asia), Sendai, Japan, 20–23 September 2016; Volume 9, pp. 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, J. Protection and Renewal of Historical and Cultural Blocks at the Micro-level: A Case Study of Pingjiang Historic and Cultural Block in Suzhou. Urban Plan. Forum 2017, 6, 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Siragusa, A.; Martinez-Bckstrm, N.; Andersson, C.; Petrella, L.; Zamorano, L. Global Public Space Toolkit from Global Principles to Local Policies and Practice; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, S.P. Instability of statistical factor analysis. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2004, 132, 1805–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 6th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, L.; Cheibub, B.L. Accessible or not? That is the Question! Analyzing the accessibility of the historic touristic city center of Paraty (RJ). Rev. Tur. Análise 2020, 31, 358–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Yang, T.; Turner, A. Normalising least angle choice in Depthmap—And how it opens up new perspectives on the global and local analysis of city space. J. Space Syntax 2012, 3, 153–193. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; Yin, B. The impact of the built-up environment of streets on pedestrian activities in the historical area. AEJ Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Jiang, Y.; He, J. Quantitative Evaluation on Street Vitality: A Case Study of Zhoujiadu Community in Shanghai. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashihara, Y. Exterior Design in Architecture; Van Nostrand Reinhold: Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Forczek-Brataniec, U. Visible Space: A Visual Analysis in the Lanscape Planning and Designing; Cracow University of Technology: Cracow, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Chiou, S.-C. A Study on the Sustainable Development of Historic District Landscapes Based on Place Attachment among Tourists: A Case Study of Taiping Old Street, Taiwan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, R. Social and community issues. In Urban Regeneration; Roberts, P., Sykes, H., Granger, R., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2016; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Faro Convention or Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, R.A. Heritage conservation: Authenticity and vulnerability of living heritage sites in Melaka state. Kaji. Malays. 2017, 35 (Suppl. 1), 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyyamoğlu, M.; Akçay, A.Ö. Assessment of Historic Cities within the Context of Sustainable Development and Revitalization: The Case of the Walled City North Nicosia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabie, S. Heritage Recognition Between Evaluation and Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference of Contemporary Affairs in Architecture and Urbanism (ICCAUA-2021), Alanya, Turkey, 20–21 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jinchang Local Chronicles Compilation Commission. Annals of Jinchang District; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Administrative Measures for the Protection and Utilization of Historical Buildings in Suzhou (SFGZ [2021] No. 12); Suzhou Municipal People’s Government: Suzhou, China, 2021. Available online: https://www.suzhou.gov.cn/szsrmzf/szfgfxwjk/202203/ef57ff2d8f84485383ecbdc4f2a5a98f.shtml (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Special Plan for the Protection of Suzhou Historical and Cultural City. 2035. Available online: https://www.suzhou.gov.cn/szsrmzf/szyw/202010/c2df23411f9d42eb9db497e00ae714bf.shtml (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Protection Planning of Changmen Historical and Cultural Block in Suzhou; Suzhou Natural Resources and Planning Bureau: Suzhou, China, 2016. Available online: http://zrzy.jiangsu.gov.cn/sz/ghcgy/201904/t20190403_769438.htm (accessed on 29 April 2016).

| Vitality Evaluation | Categories (Target Layer) | Indicators (Rule Layer) | Main Influence Factors (Index Layer) | Main Data Acquisition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitality of public spaces in historical and cultural blocks | Basic characteristics of public space | Accessibility | Spatial accessibility | Traffic potential of the inner space of the block | AMAP(AutoNavi) data Planning information |

| Traffic convenience | The density of public transport facilities around public space | AMAP(AutoNavi) data POI data | |||

| Comfort | Spatial scale | The scale of public open spaces such as streets | Planning Information | ||

| Green view Ratio | The proportion of green space/plants in user’s vision | Field research Baidu Street View | |||

| Sanitary | Cleanliness of public space | Field research Urban management data Network evaluation | |||

| Rest/Recreational facilities | Number of rest facilities in public space | Field research Urban management data Network evaluation | |||

| Functionality | Mixedness | Mixing degrees of functional categories | AMAP(AutoNavi) data POI data Network evaluation | ||

| Function density | The density of peripheral functions of public space | Field research AMAP(AutoNavi) data POI data | |||

| Impact | Function service scope/attraction | AMAP(AutoNavi) data POI data | |||

| Characteristics of History and Culture | Characteristics of material elements | Historical Value | The historical and cultural value of sample space | Planning Information Network evaluation | |

| Authenticity | The authenticity and integrality of building heritages | Planning Information Field research | |||

| Characteristics of non-material elements | Culture experience | Participation and richness of cultural experience | Field research Network evaluation | ||

| Vitality Evaluation | Categories (Target Layer) | Indicators (Rule Layer) | Main Influence Factors (Index Layer) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitality of Public Spaces in Historical and Cultural Blocks | Basic characteristics of public space | 0.688 | Accessibility | 0.430 | Spatial accessibility | 0.671 |

| Traffic convenience | 0.329 | |||||

| Comfort | 0.247 | Spatial scale | 0.448 | |||

| Green view Ratio | 0.169 | |||||

| Sanitary | 0.155 | |||||

| Rest/Recreational facilities | 0.228 | |||||

| Functionality | 0.323 | Mixedness | 0.466 | |||

| Function density | 0.189 | |||||

| Impact | 0.345 | |||||

| Characteristics of History and Culture | 0.312 | Characteristics of material elements | 0.542 | Historical Value | 0.583 | |

| Authenticity | 0.417 | |||||

| Characteristics of non-material elements | 0.458 | Culture experience | 1 | |||

| Categories | Indicators | Main Influence Factors | Assessment Method | Evaluation Criteria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Description | ||||

| Basic characteristics of public space | Accessibility | Spatial accessibility | Integration, Choice, etc. (Depthmap, ArcGIS) | 5 | Excellent |

| 4 | Good | ||||

| 3 | Normal | ||||

| 2 | Poor | ||||

| 1 | Very poor | ||||

| Traffic convenience | Kernel density (ArcGIS) based on POI. | 5 | Excellent | ||

| 4 | Good | ||||

| 3 | Normal | ||||

| 2 | Poor | ||||

| 1 | Very poor | ||||

| Comfort | Spatial scale | D/H | 5 | D/H ≥ 2 | |

| 4 | 2>D/H ≥ 1.5 | ||||

| 3 | 1.5>D/H ≥ 1 | ||||

| 2 | 1>D/H ≥ 0.5 | ||||

| 1 | 0.5>D/H | ||||

| Green view Ratio | Semantic Image Segmentation | 5 | Excellent | ||

| 4 | Good | ||||

| 3 | Normal | ||||

| 2 | Poor | ||||

| 1 | Very poor | ||||

| Rest/Recreational facilities | Referring to L-rf (length of rest/recreational facilities) | 5 | L-rf ≥ 6 m | ||

| 4 | 6 m>L-rf ≥ 4 m | ||||

| 3 | 4 m>L-rf ≥ 2 m | ||||

| 2 | 2 m>L-rf>0 m | ||||

| 1 | 0 m | ||||

| Sanitary | Consulting the environmental assessment standards of urban public space | 5 | The environment is clean and tidy; The enclosed interface is free of garbage, dirt and odor | ||

| 4 | The environment is clean with a little garbage, stain or odor on the enclosed interface | ||||

| 3 | The environment is clean; with a small amount of garbage or dirt or odor on the enclosed interface | ||||

| 2 | The cleanliness of environment is poor, with some garbage, stains or peculiar smell on the enclosed interface | ||||

| 1 | The cleanliness of the environment is poor, with a lot of garbage or dirt or odor on the enclosed interface | ||||

| Functionality | Mixedness | Statistics of function types of POI(ArcGIS) | 5 | Excellent | |

| 4 | Good | ||||

| 3 | Normal | ||||

| 2 | Poor | ||||

| 1 | Very poor | ||||

| Density | Statistics of POI density (ArcGIS) | 5 | Excellent | ||

| 4 | Good | ||||

| 3 | Normal | ||||

| 2 | Poor | ||||

| 1 | Very poor | ||||

| Impact | Comprehensive evaluation and scoring | 5 | High impact/Nationwide scope | ||

| 4 | Relatively high impact/Regional scope | ||||

| 3 | Average impact/City scope | ||||

| 2 | Low impact/Urban district scope | ||||

| 1 | Limited impact/Block scope | ||||

| Characteristics of History and Culture | Characteristics of material elements | Historical Value | Consulting the relic protection level of the unit | 5 | provincial or national relics |

| 4 | Municipal relics | ||||

| 3 | Municipal control/cultural relics registration point | ||||

| 2 | Traditional buildings/historical buildings | ||||

| 1 | general buildings | ||||

| Authenticity | Consulting authenticity evaluation standard of Historical and Cultural Block and Administrative Measures for the Protection and Utilization of Historical Buildings in Suzhou | 5 | High authenticity, complete components, no obvious repair or transformation | ||

| 4 | Relatively high authenticity, the constituent elements are relatively complete, and the auxiliary structures have traces of repair. | ||||

| 3 | General authenticity, the constituent elements are relatively complete, the subsidiary structure is inconsistent or the traces of transformation are obvious, but the overall style is harmonious | ||||

| 2 | Low authenticity, poor condition or rebuilt, not harmonious with surrounding areas | ||||

| 1 | Poor authenticity, abandoned components or newly built, not harmonious with surrounding areas | ||||

| Characteristics of non-material elements | Culture experience | Statistics of data from review website and survey questionnaire | 5 | Excellent experience, diverse cultural display modes with multiplex interaction experience | |

| 4 | Good experience: dynamic cultural display mode with interactive experience | ||||

| 3 | Normal experience, static cultural display mode with graphic combination | ||||

| 2 | Poor experience, monotonous cultural display mode | ||||

| 1 | Very poor, Lack of cultural presentation and experience | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, X. Vitality Evaluation of Public Spaces in Historical and Cultural Blocks Based on Multi-Source Data, a Case Study of Suzhou Changmen. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114040

Zhang F, Liu Q, Zhou X. Vitality Evaluation of Public Spaces in Historical and Cultural Blocks Based on Multi-Source Data, a Case Study of Suzhou Changmen. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114040

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Fang, Qi Liu, and Xi Zhou. 2022. "Vitality Evaluation of Public Spaces in Historical and Cultural Blocks Based on Multi-Source Data, a Case Study of Suzhou Changmen" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114040