Using a Mixed-Methods Needs Analysis to Ensure the Sustainability and Success of English for Nursing Communication Courses: Improving Nurse-Patient Engagement Practices in Globalized Health Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Engagement in Nursing Communication

1.2. Perceptions/Practices of Engagement in Nursing Communication

1.3. Teaching Engagement in ESP Nursing Communication

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Needs Analysis

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

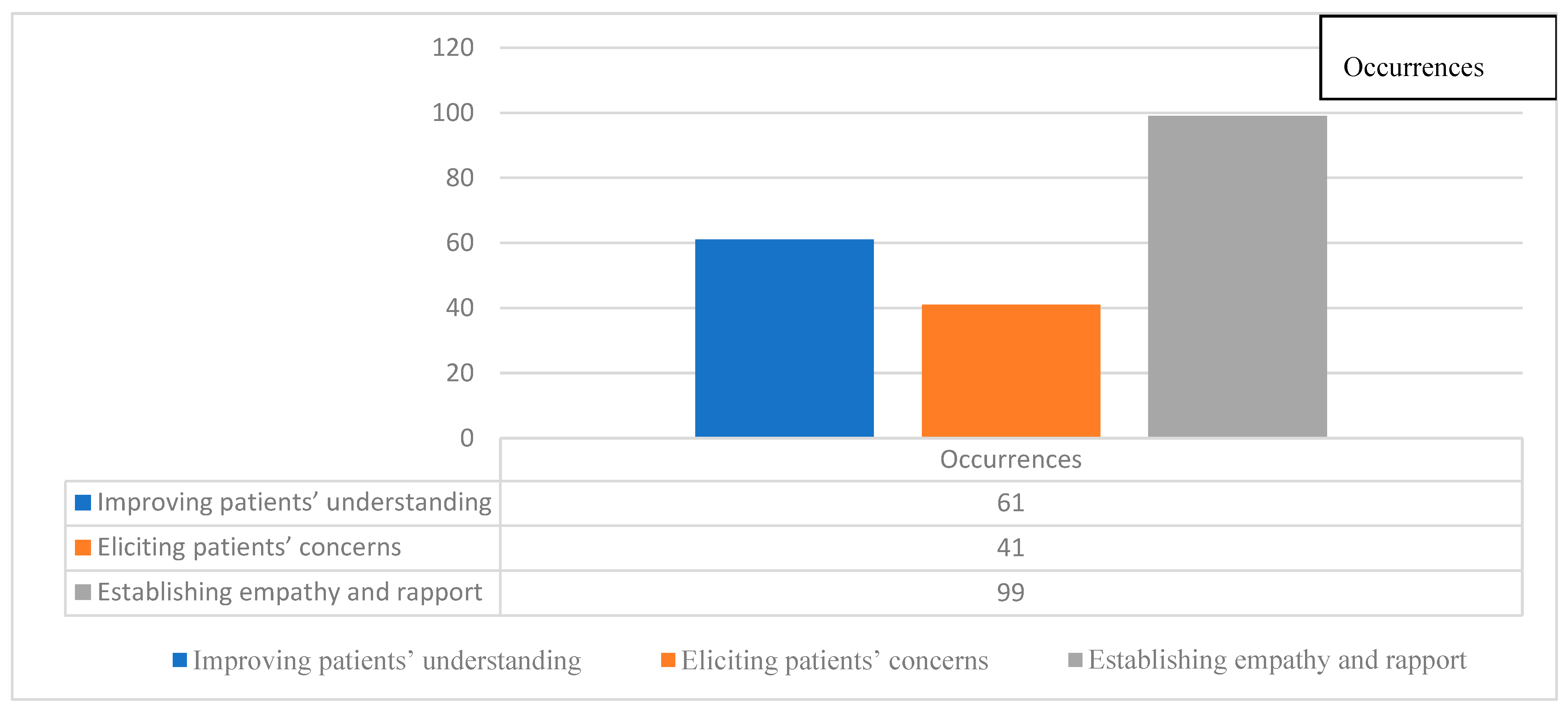

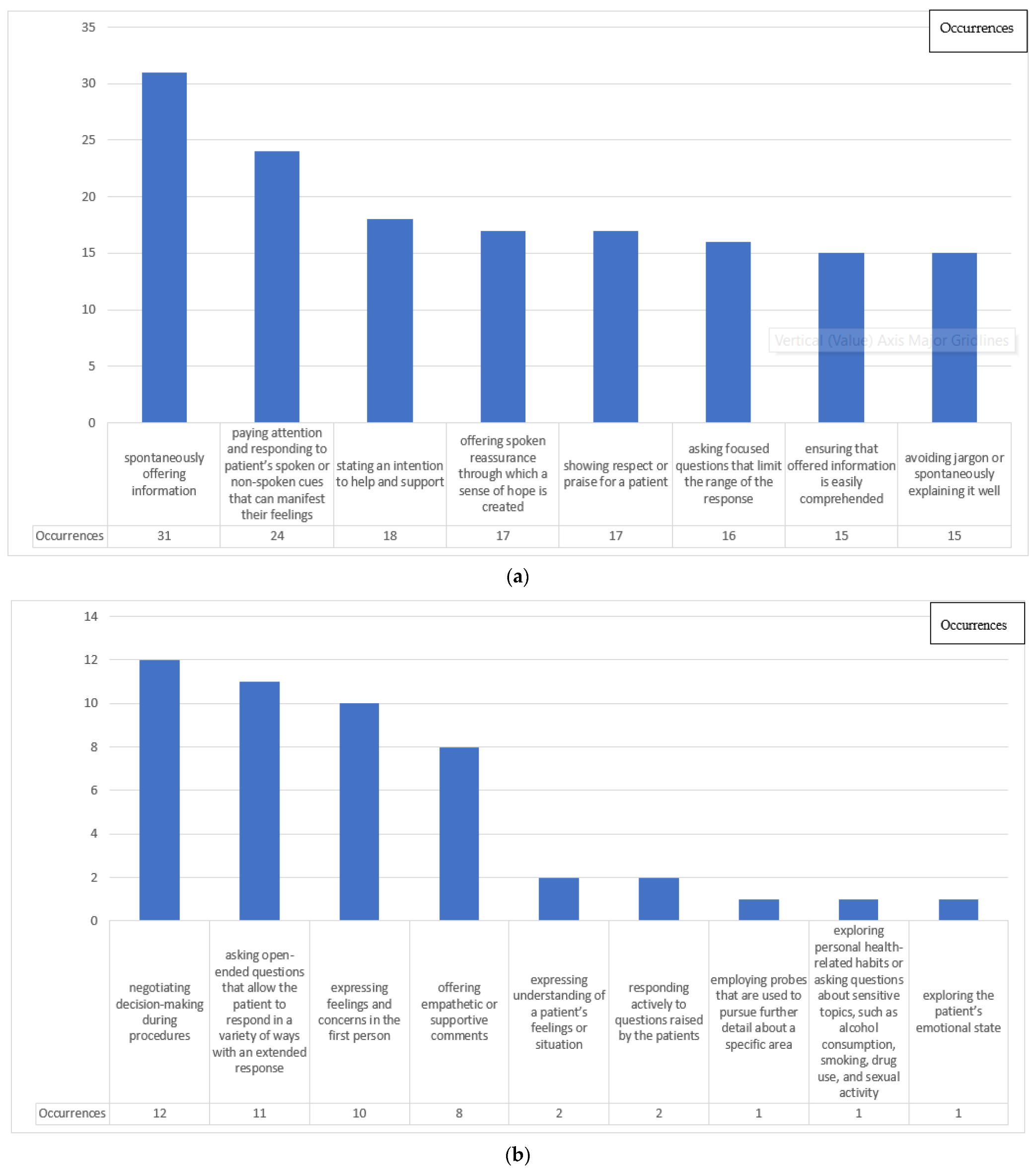

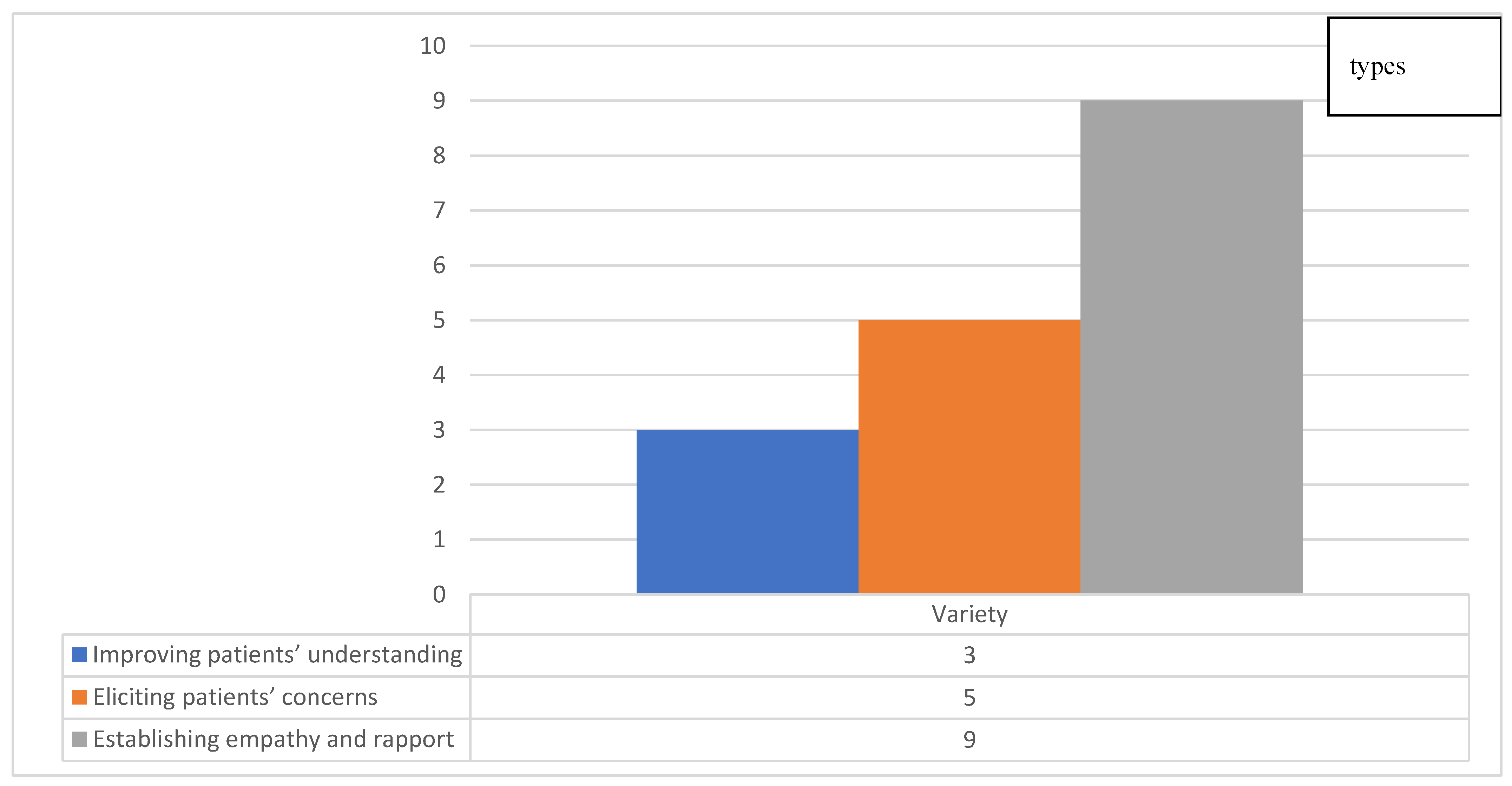

3.1. Analysis of Engagement Strategies

3.2. Move Analysis

3.3. Speech Function Analysis

3.4. Post-Observation Comments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. The Observation Guide for Nursing Engagement with Patients

| Date: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Place | Clinical Tasks | Nurse/Patient’s Talk | Functions of Talk | Comments |

Appendix A.2. Post-Observation Interview Questions

- What was the purpose of your saying this?

- During this nurse-patient interaction, did you have any specific spoken strategy to better understand patients’ ideas?

- During this nurse-patient interaction, did you say anything to make yourself better understood by your patients?

- During this nurse-patient interaction, did you say anything to elicit as many patients’ concerns as possible, especially about their emotional needs?

- During this nurse-patient interaction, did you say anything to build empathy and rapport with the patient?

- Can you comment on your engagement practices during this nurse-patient interaction?

References

- Candlin, S.; Roger, P. Communication and Professional Relationships in Healthcare Practice; Equinox Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, K.; Koteyko, N. Exploring Health Communication: Language in Action; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, S.; Berg, A.; Zimmermann, M.; Wüste, K.; Behrens, J. Nurse-patient interaction and communication: A systematic literature review. J. Public Health 2009, 17, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, C.R.; Dearing, K.S.; Berry, J.A.; Johnson, M.J. Nurse practitioners communication styles and their impact on patient outcomes: An integrated literature review. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2008, 20, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.B. Patient-centeredness: A new approach. Nephrol. News Issues 2002, 16, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, L.A.; Treiman, K.; Rupert, D.; Williams-Piehota, P.; Nadler, E.; Arora, N.K.; Lawrence, W.; Street, R.L. Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: A literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Patient-Centred Care: Improving Quality and Safety through Partnerships with Patients and Consumers. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/PCC_Paper_August.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- Department of Health. Treating Patients as People. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/treating-patients-as-people (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- Hospital Authority. Hospital Authority Strategic Plan 2017–2022. Available online: http://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/cad_bnc/AOM-P1236.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- National Academy of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Improving Patient Satisfaction with High-Quality Nursing Services. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s10006/201301/0b824411fa464505a9ed48de232c0be4.shtml (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- Fortin, A.H. Communication skills to improve patient satisfaction and quality of care. Ethn. Dis. 2002, 12, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Price, E.G.; Cooper, L.A. Hypertension in African Americans: Strategies to help achieve blood pressure goals. Consultant 2003, 43, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, M.K.; Preuss, G. Models of care: The influence of nurse communication on patient safety. Nurs. Econ. 2002, 20, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzan, U.; Hirsch, E.; Walter, G.; Lurie, I.; Aviram, S.; Bloch, Y. Comprehension and companionship in the emergency department as predictors of treatment adherence. Australas. Psychiatry 2012, 20, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, N.; Bower, P. Patient-centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: A review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 48, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredart, A.; Bouleuc, C.; Dolbeault, S. Doctor-patient communication and satisfaction with care in oncology. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2005, 17, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.K. Interacting with cancer patients: The significance of physicians’ communication behavior. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.M.; Street, R.L. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, L.K.; Barrett, R.; Ellington, L. Difficult communication in nursing. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2006, 38, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kee, J.W.Y.; Khoo, H.S.; Lim, I.; Koh, M.Y.H. Communication skills in patient-doctor interactions: Learning from patient complaints. Health Prof. Educ. 2018, 4, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, B.; Kuhn, N. Communication gaffes: A root cause of malpractice claims. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2003, 16, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, F.A.S.; Kayes, N.M.; McPherson, K.M.; Worrall, L.E. Engaging people experiencing communication disability in stroke rehabilitation: A qualitative study. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2018, 53, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, Y.L.; Zeitz, C.J.; Fredericks, B. Study protocol: Establishing good relationships between patients and health care providers while providing cardiac care. Exploring how patient-clinician engagement contributes to health disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians in South Australia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Pun, J. Views of Hospital Nurses and Nursing Students on Nursing Engagement—Bridging the Gap Through Communication Courses. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Zheng, R.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Sun, R. Caring for dying cancer patients in the Chinese cultural context: A qualitative study from the perspectives of physicians and nurses. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, B.M.C.; Rossiter, J.C. Caring in nursing: Perceptions of Hong Kong nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2000, 9, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangaltsos, A. Medical Thought; M. Barbounaki: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kralik, D.; Koch, T.; Wotton, K. Engagement and detachment: Understanding patients’ experiences with nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 26, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freihat, P.S.; Al-Makhzoomi, K. An English for specific purposes (ESP) course for nursing students in Jordan and the role a needs analysis played. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Pun, J.K.H.; Chan, E.A.; Murray, K.A.; Slade, D.; Matthiessen, C.M.I.M. Complexities of emergency communication: Clinicians’ perceptions of communication challenges in a trilingual emergency department. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 26, 3396–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pun, J.K.H.; Chan, E.A.; Wang, S.; Slade, D. Health professional-patient communication practices in East Asia: An integrative review of an emerging field of research and practice in Hong Kong, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Mainland China. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corlett, J. The perceptions of nurse teachers, student nurses and preceptors of the theory-practice gap in nurse education. Nurse Educ. Today 2000, 20, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarania, A.; Su, S. Mobile assisted ESP vocabulary learning-A case study of a nursing english course. Taiwan Int. ESP J. 2016, 8, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, L.; Yang, X.Y.; Jian, Y.J.; Li, J. Attempt and result analysis of nursing speciality of the ESP teaching for high duty nurses specialized. Contin. Med. Educ. 2006, 20, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.; Talebinezhad, M.R. The impact of teaching EFL medical vocabulary through collocations on vocabulary retention of EFL medical students. Adv. Lang. Lit. Stud. 2018, 9, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahipour, P.; Saba, Z. ESP vocabulary instruction: Investigating the effect of using a game oriented teaching method for learners of english for nursing. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2012, 3, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, C.; Rolls, C.; Campbell, M. Nurses on the move: Evaluation of a program to assist international students undertaking an accelerated bachelor of nursing program. Contemp. Nurse 2007, 25, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, S. Using corpus-based discourse analysis for curriculum development: Creating and evaluating a pronunciation course for internationally educated nurses. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2019, 53, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, M.; Swain, M. Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Appl. Linguist. 1980, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymes, D. On Communicative Competence; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, J.; Edinberg, M. Communication in the Nursing Context; Pearson: Norwalk, CT, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zanten, M.; Boulet, J.R.; McKinley, D. Using standardized patients to assess the interpersonal skills of physicians: Six years’ experience with a high-stakes certification examination. Health Commun. 2007, 22, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bays, A.M.; Engelberg, R.A.; Back, A.L.; Ford, D.W.; Downey, L.; Shannon, S.E.; Doorenbos, A.Z.; Edlund, B.; Christianson, P.; Arnold, R.W.; et al. Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: Evaluation of a small-group, simulated patient intervention. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paltridge, B.; Phakiti, A. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics: A Practical Resource; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hafner, C.; Miller, L. English in the Disciplines: A Multidimensional Model for ESP Course Design; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow, L. Introducing Course Design in English for Specific Purposes; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gass, J. Needs analysis and situational analysis: Designing an ESP curriculum for Thai nurses. Engl. Specif. Purp. World 2012, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bosher, S.; Smalkoski, K. From needs analysis to curriculum development. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2002, 21, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolster, D.; Manias, E. Person-centred interactions between nurses and patients during medication activities in an acute hospital setting: Qualitative observation and interview study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manias, E.; Street, A. Legitimation of nurses’ knowledge through policies and protocols in clinical practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.S.; Brennan, J.S.; Chasen, S.T. Clinical estimation of fetal weight and the Hawthorne effect. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2008, 141, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarney, R.; Warner, J.; Iliffe, S.; van Haselen, R.; Griffin, M.; Fisher, P. The Hawthorne effect: A randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.; Wetherell, M. Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Eggins, M.; Slade, D. Analysing Casual Conversation; Equinox: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Matthiessen, C.M.I.M. An Introduction to Functional Grammar; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.R. English Text: System and Structure; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Thornbury, S.; Slade, D. Conversation: From Description to Pedagogy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Matthiessen, C.M.I.M. Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, J.M.; Coulthard, R.M. Towards an Analysis of Discourse: The English Used by Teachers and Pupils; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Pun, J.; Matthiessen, C.M.I.M.; Williams, G.; Slade, D. Using Ethnographic Discourse Analysis to Understand Doctor-Patient Interactions in Clinical Settings; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, D.; Matthiessen, C.; Lock, G.; Pun, J.; Lam, M. Patterns of interaction in doctor-patient communication and their impact on health outcomes. In The Usage-Based Study of Language Learning and Multilingualism; Ortega, L., Tyler, A., Park, H., Uno, M., Eds.; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, D.; Pun, J.; Lock, G.; Eggins, S. Potential risk points in doctor-patient communication: An analysis of Hong Kong emergency department medical consultations. In Language at Work: Analysing Language Use in Work, Education, Medical and Museum Contexts; Joyce, H.S., Ed.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2016; pp. 146–165. [Google Scholar]

- Candlin, S. Therapeutic Communication: A Lifespan Approach; Pearson Education: French’s Forest, NSW, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kourkouta, L.; Papathanasiou, I. Communication in Nursing Practice. Mater. Soc. Med. 2014, 26, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, N.L.; Green, D.C.; Kao, A.C.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Wu, V.Y.; Cleary, P.D. How are patients’ specific ambulatory care experiences related to trust, satisfaction, and considering changing physicians? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2002, 17, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, H.; Yamazaki, Y. How applicable are western models of patient-physician relationship in Asia? Changing patient-physician relationship in contemporary Japan. Int. J. Jpn. Sociol. 2005, 14, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.N.; Sun, H.M.; Huang, J.W.; Li, M.L.; Huang, R.R.; Li, N. Simulation-based empathy training improves the communication skills of neonatal nurses. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2018, 22, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, D.S.; Edwardsen, E.A.; Gordon, H.S. Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication. Arch. Intern. Med. 2015, 168, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Shi, Z. Nurses’ communication ability in nurse-patient conflict. J. Nurs. Sci. 2010, 25, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Li, X. Investigation on influencing factors of nurse-patient communication competence of nursing staff. Chin. Nurs. Res. 2013, 27, 1951–1953. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.A. Clinicians’ accuracy in perceiving patients: Its relevance for clinical practice and a narrative review of methods and correlates. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 84, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigert, H.; Dellenmark Blom, M.; Bry, K. Parents’ experiences of communication with neonatal intensive-care unit staff: An interview study. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, D.; Manidis, M.; McGregor, J.; Scheeres, H.; Chandler, E.; Stein-Parbury, J.; Dunston, R.; Herke, M.; Matthiessen, C.M.I.M. Communicating in Hospital Emergency Departments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Flowerdew, J. Discourse in English Language Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heisler, M.; Vijan, S.; Anderson, R.M.; Ubel, P.A.; Bernstein, S.J.; Hofer, T.P. When do patients and their physicians agree on diabetes treatment goals and strategies, and what difference does it make? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobb, E.A.; Butow, P.N.; Barratt, A.; Meiser, B.; Gaff, C.; Young, M.A.; Haan, E.; Suthers, G.; Gattas, M.; Tucker, K. Communication and information-giving in high-risk breast cancer consultations: Influence on patient outcomes. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 90, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, E.L.; Schrader, D.C. Health care provider communicator style and patient comprehension of oral contraceptive use. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2001, 13, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Tony (a Pseudonynm) |

|---|---|

| Age | 45 |

| Gender | Male |

| Nationality | Korean |

| Medical conditions | 1. pneumonia |

| 2. alcoholism | |

| 3. hyperthyroidism | |

| 4. hypokalemia. | |

| Department | After being treated in the intensive care unit (ICU) for five days, the patient was admitted to the Department of Respiratory Medicine. |

| Initiation | Expected Response (Synoptic: Finishes the Exchange) | |

|---|---|---|

| Response | Follow-Up | |

| Statement | Acknowledgement | Follow-up Feedback |

| Contradiction | ||

| Offer | Acceptance | |

| Rejection | ||

| Acknowledgement | ||

| Question (open)/(yes/no) | Answer | |

| Disclaimer | ||

| Command | Compliance | |

| Refusal | ||

| Greeting | Response to Greeting | |

| Unexpected/Discretionary Response (Dynamic: Opens out the Exchange) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Response | Follow-Up | |

| Tracking | Checking | |

| Confirming | Response to Tracking | |

| Clarifying | ||

| Challenging | Disengaging | Response to Challenging |

| Challenging | ||

| Countering | Feedback | |

| No response | ||

| Engagement Strategies | Moves | Speech Functions | Speaker | Talk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation | Statement | Nurse | Tony, things are ready. | |

| Question (yes/no) | Can I start the injection now? | ||

| Response | Answer | Patient | OK. | |

| Initiation | Command | Nurse | Tony, please put your right hand flat. | |

| negotiating shared decision-making during procedures | Question (yes/no) | Should I tie a tourniquet first to select a blood vessel? = =This blood vessel is fine, and I will do the injection here later, OK? | ||

| Response | Answer | Patient | = =Ye-ye-ye-yes. | |

| Initiation | Offer | Nurse | Now I will disinfect you. |

| Statement | The disinfectant is a little cool. | |||

| Command | Please bear with me. | |||

| Offer | I’m putting a tourniquet on you. | ||

| Statement | It may be a little tight, but it will make the blood vessel more obvious. | |||

| offering spoken reassurance through which a sense of hope is created | Question (yes/no) | Would you please hold on for a while? | ||

| Response | Answer | Patient | OK [Nodding]. |

| Ranking | Occurrences (n) | Engagement Strategies | Types of Engagement | Examples from Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | spontaneously offering information | Improving patients’ understanding | Nurse: Your body temperature is 36.7 °C, pulse is 72 beats/min, breathing is 20 times/min, and blood pressure is 150/84 mmHg. [measuring vital signs] |

| 2 | 24 | paying attention and responding to patient’s spoken or non-spoken cues that can manifest their feelings | Establishing empathy and rapport | Nurse: Is the water temperature OK? [patient hygiene] |

| 3 | 18 | stating an intention to help and support | Establishing empathy and rapport | Nurse: If you feel uncomfortable or need help, please ring the bell. [taking injections] |

| 4 | 17 | offering spoken reassurance through which a sense of hope is created | Establishing empathy and rapport | Nurse: Don’t worry! They are all very kind and very professional in providing medical care. You will be well cared for in their department, and your family will be with you every day. [patient education] |

| 17 | showing respect or expressing praise for a patient | Establishing empathy and rapport | Nurse: Very good; very good physical activity. [patient hygiene] | |

| 6 | 16 | asking focused questions that limit the range of the response | Eliciting patients’ concerns | Nurse: Tony, is it comfortable for you to lie like this? [taking injections] |

| 7 | 15 | offering information that is easily comprehended | Improving patients’ understanding | Nurse: Mucosolvan can dissolve the phlegm and clear it from your lungs, which will make it easier for you to cough out the phlegm and help the inflammation in your lungs to get better faster. [taking injections] |

| 15 | avoiding jargon or spontaneously explaining it well | Improving patients’ understanding | Nurse: Mucosolvan can dissolve the phlegm and clear it from your lungs, which will make it easier for you to cough out the phlegm and help the inflammation in your lungs to get better faster. [taking injections] | |

| 9 | 12 | negotiating decision-making during procedures | Eliciting patients’ concerns | Nurse: Which hand do you prefer? [taking injections] |

| 10 | 11 | asking open-ended questions that allow the patient to respond in a variety of ways with an extended response | Eliciting patients’ concerns | Nurse: How do you feel today? [taking injections] |

| 11 | 10 | expressing care or/and concerns in the first person | Establishing empathy and rapport | Nurse: I will measure your axillary temperature, so first, I need to wipe off the sweat under your armpit. [measuring vital signs] |

| 12 | 8 | offering empathetic or supportive comments | Establishing empathy and rapport | Nurse: You’re recovering well, and I think you will be transferred out of the ICU soon! [patient hygiene] |

| 13 | 2 | expressing understanding of a patient’s feelings or situation | Establishing empathy and rapport | Patient: The lights at night are too bright. Nurse: Sorry! We forgot to check. Tonight, I will ask the nurse on duty to turn down the lights, OK? [taking injections] |

| 2 | responding actively to questions raised by the patients | Establishing empathy and rapport | Patient: Why wipe off the sweat? I don’t do that at home. Nurse: Because sweat can make the temperature measurement inaccurate. [measuring vital signs] | |

| 15 | 1 | employing probes that are used to pursue further detail about a specific area | Eliciting patients’ concerns | Patient: My body is getting better, but I didn’t sleep very well last night. Nurse: Why is that? [taking injections] |

| 16 | 1 | exploring personal health-related habits or asking questions about sensitive topics, such as alcohol consumption, smoking, drug use, and sexual activity | Eliciting patients’ concerns | Nurse: Are you allergic to any medicine? [taking injections] |

| 1 | exploring the patient’s emotional state | Establishing empathy and rapport | Patient: Uh...I am a little nervous. Nurse: What’s the matter? [patient education] |

| Moves | Initiation | Response | Follow-Up | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moves that were for the purpose of engagement | 66 | 1 | 15 | 82 |

| Total number of Moves made by the nurse | 86 | 2 | 45 | 133 |

| Percentage | 76.74% | 50% | 33.33% | 61.65% |

| Question Types | Open | Yes/No |

|---|---|---|

| Questions for the purpose of engagement | 11 | 24 |

| Total number of Questions asked by the nurse | 11 | 27 |

| Percentage | 100% | 88.89% |

| Communication Strategies | Examples |

|---|---|

| Nurse: How do you feel today? [taking injections] |

| Patient: My body is getting better, but I didn’t sleep very well last night. Nurse: Why is that? [taking injections] |

| |

| Patient: Uh...I am a little nervous. Nurse: What’s the matter? [patient education] |

| Communication Strategies | Examples |

|---|---|

| I raised the head of the bed. Do you feel comfortable? [measuring vital signs] |

| Tony, is it comfortable for you to lie like this? [taking injections] |

| Can I take your blood pressure here in a minute? [measuring vital signs] |

| Are you allergic to any medicine? [taking injections] |

| Can I start the injection now?[taking injections] |

| Do you need me to help you go to the bathroom? [taking injections] |

| |

| Nurse: I’m putting a tourniquet on you. It may be a little tight, but it will make the blood vessel more obvious. Would you please hold on for a while? [taking injections] |

| Speaker | Talk |

|---|---|

| Nurse | Which hand do you prefer? |

| Patient | Right hand. |

| Nurse | Please give me your right hand so I can check the skin and blood vessels. |

| Patient | [give his right hand] |

| Nurse | The skin on the back of your right hand is fine, and the blood vessels are elastic. We can use the right side for the injection. |

| Patient | Good. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Q.; Pun, J.; Huang, S. Using a Mixed-Methods Needs Analysis to Ensure the Sustainability and Success of English for Nursing Communication Courses: Improving Nurse-Patient Engagement Practices in Globalized Health Care. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114077

Huang Q, Pun J, Huang S. Using a Mixed-Methods Needs Analysis to Ensure the Sustainability and Success of English for Nursing Communication Courses: Improving Nurse-Patient Engagement Practices in Globalized Health Care. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114077

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Qing, Jack Pun, and Shuping Huang. 2022. "Using a Mixed-Methods Needs Analysis to Ensure the Sustainability and Success of English for Nursing Communication Courses: Improving Nurse-Patient Engagement Practices in Globalized Health Care" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114077

APA StyleHuang, Q., Pun, J., & Huang, S. (2022). Using a Mixed-Methods Needs Analysis to Ensure the Sustainability and Success of English for Nursing Communication Courses: Improving Nurse-Patient Engagement Practices in Globalized Health Care. Sustainability, 14(21), 14077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114077