How Does Financial Literacy Affect Digital Entrepreneurship Willingness and Behavior—Evidence from Chinese Villagers’ Participation in Entrepreneurship

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. DE Theory and Participating in DE

2.2. Impact of FL on DE Willingness and Behavior

2.3. Mediating Role of FI

2.4. Moderating Effect and Moderated-Mediating Effect of DL

3. Research Methods and Variable Measurement

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Reliability and Validity Analysis

3.4. Descriptive Statistical and Correlation Analysis

3.5. Common-Method Variance

4. Results

4.1. Main Effect Analysis

4.2. Mediating Effect Analysis

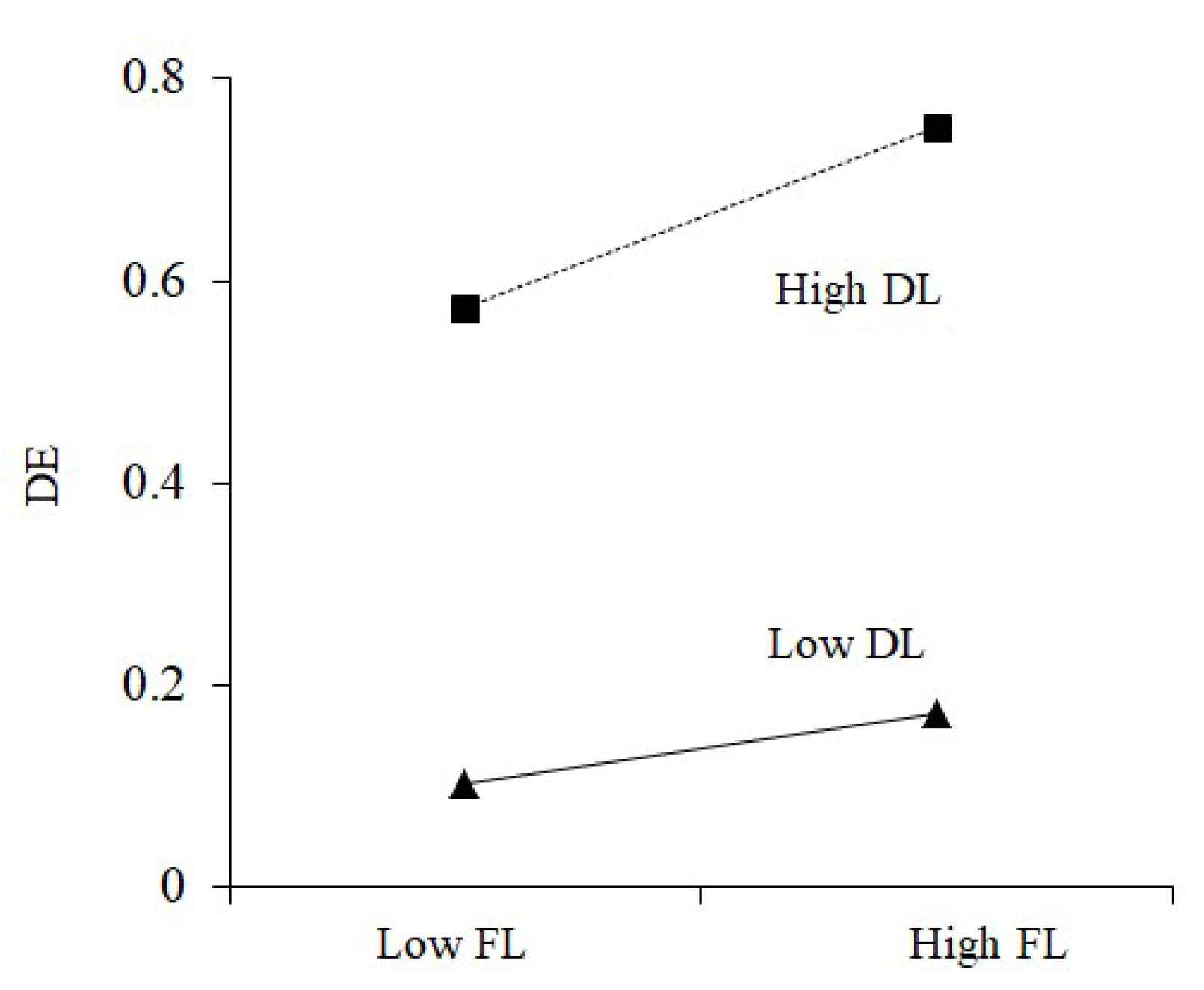

4.3. Moderating Effect Analysis

4.4. Moderated-Mediating Effect Analysis

4.5. Analysis of PSC vs. NPSC

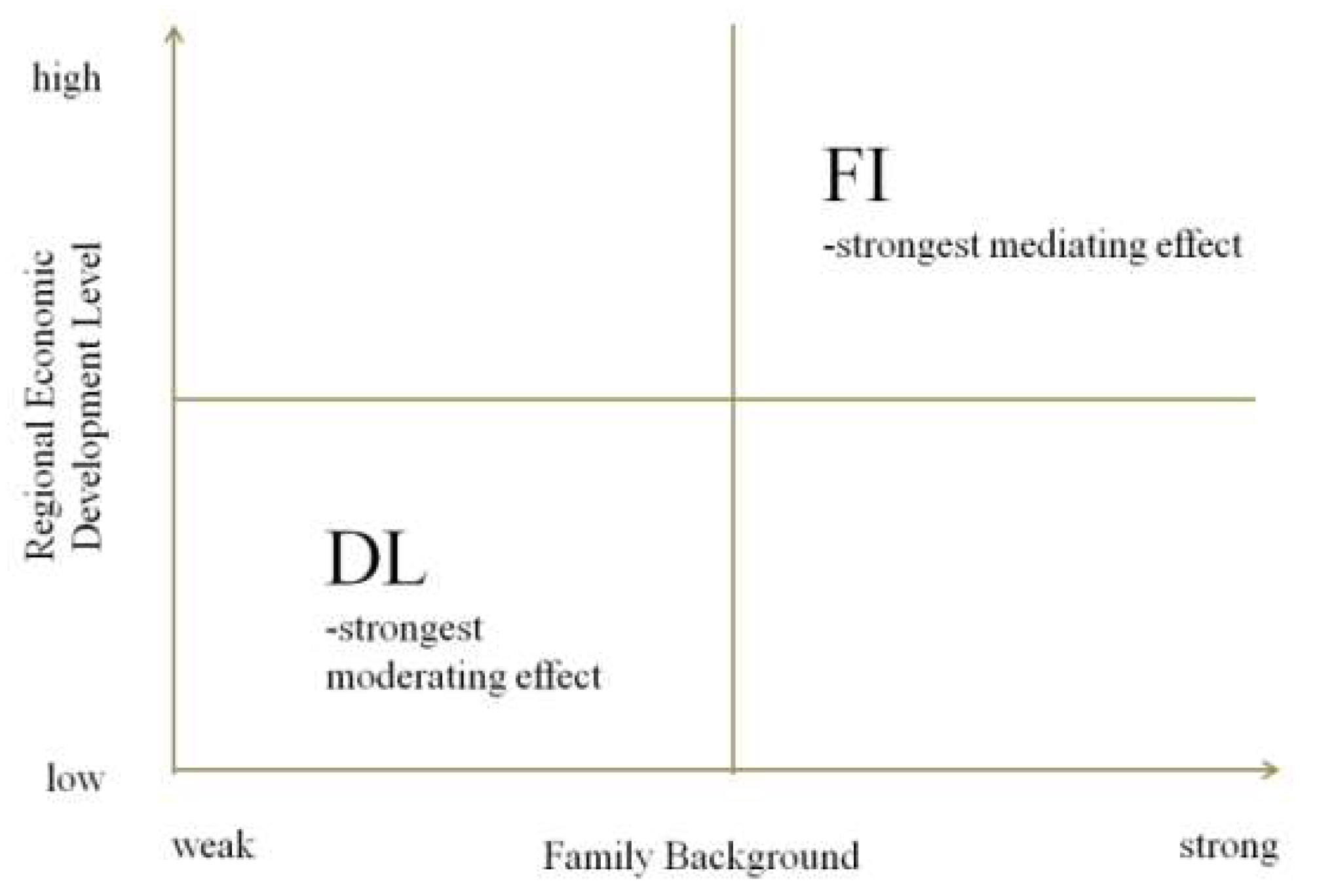

4.6. Comparison of Family Background Differences among Entrepreneurial Groups

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Main Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Contribution and Implications

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bruton, D.G.; Ketchenjr, J.D.; Ireland, D.R. Entrepreneurship as a solution to poverty. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Palmer, C.; Kailer, N.; Kallinger, L.F.; Spitzer, J. Digital entrepreneurship: A research agenda on new business models for the twenty-First century. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 353–375. [Google Scholar]

- Nambisan. Digital Entrepreneurship: Toward a Digital Technology Perspective of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. Forthcom. 2017, 41, 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, X.; Santos, S.C.; Morris, M.H. Overcoming Barriers to Technology Adoption When Fostering Entrepreneurship Among the Poor: The Role of Technology and Digital Literacy. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.; Bruton, G.D.; Chen, J. Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.H.; Xiong, X.P. Financial Literacy Assessment of Rural Residents and Research on Influencing Factors-Based on survey data of Hubei and Henan provinces. China Rural. Surv. 2017, 4, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.L.; Kong, R. Financial Literacy, Entrepreneurial Training and Farmers’ entrepreneurial decision making. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2019, 18, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.K.; Lin, M.L.; Liao, Y.K. Understanding factors influencing information communication technology adoption behavior: The moderators of information literacy and digital skills. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.T. Digital entrepreneurship: A study on elements and kernel generation mechanism. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2020, 42, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Scuotto, V.; Morellato, M. Entrepreneurial Knowledge and Digital Competence: Keys for a Success of Student Entrepreneurship. J. Knowl. Econ. 2013, 4, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, Q.H. The use of digital finance and Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Behavior. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2019, 8, 112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hafezieh, N.; Akhavan, P.; Eshraghian, F. Exploration of process and competitive factors of entrepreneurship in digital space: A multiple case study in Iran. Educ. Bus. Soc. Contemp. Middle East. Issues 2011, 4, 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, N.; Khalid, F. Entrepreneurship and Innovation in the Digital Economy. Lahore J. Econ. 2016, 21, 273–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dy, A.M.; Martin, L.; Marlow, S. Emancipation through digital entrepreneurship? A critical realist analysis. Organization 2018, 25, 585–608. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.Y.; Guo, H.D. Entrepreneurial Atmosphere, Social Network and Entrepreneurial Intention of Farmers. China Rural. Obs. 2012, 5, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Ye, Y.M.; Kang, X.L.; Wu, C.Y. Selection of Farmers’ E-commerce entrepreneurial Behaviors and Analysis of influencing Factors—Based on data of 150 farmers’ E-commerce entrepreneurs in Jiangxi Province. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2019, 18, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.Y.; Jiang, F.; Yuan, Y.Y. Research on the Influence of Real and Virtual Social Networks on Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Performance Based on the Analysis of intermediary Effect of Entrepreneurial Learning. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2020, 18, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, R.; Muller, E. “Push”and “Pull”Entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 1995, 12, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.Y.; Wang, C.M. Investigation and analysis on entrepreneurial motivation of Chinese entrepreneurs. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2009, 29, 285–287. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, M.Q.; Zhang, L. Research on the Influence of Financial literacy on Household financial Asset allocation. Shanghai Financ. 2019, 13, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett, D.R. Financial Literacy. Libr. J. 2015, 140, 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Huston, S.J. Measuring Financial Literacy. J. Consum. Aff. 2010, 44, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaity, M.; Rahman, M.M. The intention to use Islamic banking: An Exploratory study to measure Islamic Financial Literacy. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2019, 14, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, X.Q.; Gong, G. Research on the Influence mechanism of Financial literacy, Internet and digital financial products on financial inclusion. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Song, Q.Y.; Yin, Z.C. Analysis of Farmers’ Formal Credit Access and Credit Channel Preference—An explanation from the perspective of financial Knowledge level and education level. China Rural. Econ. 2016, 5, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Liu, P.C. Financial Development, Career choice and Entrepreneurship–Evidence from micro-surveys. Financ. Stud. 2014, 3, 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.C.; Song, Q.Y.; Wu, Y.; Peng, C.Y. Financial Knowledge, Entrepreneurial Decision and Entrepreneurial Motivation. Manag. World 2015, 5, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim, B.D.; Garrett, D.M.; Maki, D.M. The Long-Term Effects of High School Financial Curriculum Mandates. J. Public Econ. 2001, 80, 435–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence. J. Econ. Lit. 2014, 52, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, V.A.; Newman, F.A. Occupational Choice and the Process of Development. J. Political Econ. 1993, 101, 274–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Zhang, H.N. Financial Constraints and Family Entrepreneurship–Urban and Rural Differences in China. Financ. Res. 2013, 101, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Alderete, M.V. Does digital proximity between countries impact entrepreneurship. Info 2015, 17, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Xu, L. Inclusive Finance and Family Entrepreneurship Decision-making under Internet +. Financ. Econ. Res. 2017, 43, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, M.; Pais, J. Financial Inclusion and Development. J. Int. Dev. 2011, 23, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.X.; Miao, W.L. Financial Exclusion, Financial Inclusion and The Construction of China’s Inclusive Financial System. Financ. Trade Econ. 2015, 1, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wan, G.H.; Zhang, J.J.; He, Z.Y. Digital economy, financial inclusion and inclusive growth. Econ. Res. 2019, 54, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kpodar, K.R.; Andrianaivo, M. ICT, Financial Inclusion, and Growth Evidence from African Countries. Imf Work. Pap. 2011, 11, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Chen, Q.Q. Measurement of Financial inclusion of Farmers and Empirical Analysis of its Influencing factors—Based on questionnaire data from 19 provinces. Agric. Tech. Econ. 2016, 13, 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.J.; Fan, X.S. An Empirical Study on economic Spatial structure and Its Economic Spillover Effect in Underdeveloped Regions—A Case study of Henan Province. Geogr. Sci. 2006, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L. Analysis of Regional Differences and Influencing Factors of Rural Financial Inclusion in China. Financ. Theory Pract. 2012, 4, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Geach, N. The digital divide, financial exclusion and mobile phone technology: Two problems, one solution? J. Int. Trade Law Policy 2007, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.Y.; Liu, H.; Yang, H.Y. Inclusiveness and Influencing Factors of Rural Finance in China. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2018, 3, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A.D.; Shah, S.K.; Njuguna, I.N.; Porter, M.K.; Neary, J.; Maleche-Obimbo, E.; Bosire, R.; Wamalwa, C.D.; Stewart, J.G.; Slyker, A.J. Letter to the Editor: Financial incentives to motivate pediatric HIV testing-assessing the potential for coercion, inducement, and voluntariness. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2018, 78, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Yang, J.; Ren, B. Social Capital, Prior experience, and Entrepreneurial Opportunity-an interaction effect Model and its implications. Manag. World 2008, 8, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cnaan, R.A.; Moodithaya, M.S.; Femida, H. Financial Inclusion: Lessons from Rural South India. J. Soc. Policy 2012, 41, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, Y.J.; Zhang, L.Y.; Hui, Y.W. Financial Availability and Rural Family Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Study based on CHARLS data. Econ. Theory Econ. Manag. 2014, 8, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Eshet, Y. Thinking in the Digital Era: A Revised Model for Digital Literacy. Issues Inf. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2012, 7, 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Gilster, P.; Gilster, P. Digital Literacy. Digit. Lit. 1997, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Eshetalkalai, Y. Digital Literacy: A Conceptual Framework for Survival Skills in the Digital Era. J. Educ. Multimed. Hypermedia 2004, 13, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Shi, K. Empirical research on influencing Factors of online learning platform use from the perspective of Digital literacy. Chin. J. ICT Educ. 2019, 4, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Alamutka, K. Mapping digital competence: Towards a conceptual understanding. Inst. Prospect. Technol. Stud. 2011, 60, 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadyari, S.; Singh, H. Understanding the effect of e-learning on individual performance: The role of digital literacy. Comput. Educ. 2015, 82, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oggero, N.; Rossi, M.C.; Ughetto, E. Entrepreneurial spirits in women and men. The role of financial literacy and digital skills. Small Bus. Econ. Entrep. J. 2020, 55, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Islami, N.N. The effect of digital literacy toward enterpreneur behaviors through students’ intention enterpreneurship on Economics Education Study Program at Jember. IOP Conf.Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 243, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Jiang, Y.Q. Mechanism of Rural E-commerce Industrial Agglomeration and Regional Economic Coordinated Development under the background of Rural Revitalization—A Multi-case Study based on the Life Cycle theory of Industrial Clusters. China’s Rural. Econ. 2020, 2, 56–74. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for Cross-cultural Research. Cross Cult Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, G.J.; Slevin, P.D. Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D.; Lynch, J.G.; Netemeyer, R.G. The Effect of Financial Literacy and Financial Education on Downstream Financial Behaviors. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 1861–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E. Survey Measures of Web-Oriented Digital Literacy. Soc. Comput. Rev. 2005, 23, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, W. Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Ying, W.J. Empirical Analysis of Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Motivation and Exploration of Its Transformation Path. Mod. Econ. Res. 2020, 7, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobserved Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, N.L.; Hull, C.E. Market orientation digital entrepreneurship: Advantages and challengesa Web 2.0 networked world. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2013, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, S.L.; West, G.S. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions-Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER). J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1991, 45, 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, B.J.; Wen, Z.L. Methods for testing mediated regulatory models: Screening and integration. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2013, 45, 1050–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.I.; Meng, Q.S.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, J. Digital Entrepreneurship: New Trends in Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice in the Digital Age. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2015, 36, 1801–1808. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; He, X.G.; Li, Z.Y. Family Structure and Farmer Entrepreneurship: A Data Analysis based on the Survey of Thousands of Villages in China. China Ind. Econ. 2017, 3, 170–188. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X. Does family background affect college students’ academic performance? Meta-analysis based on 41 quantitative studies at home and abroad. J. Nanjing Norm. Univ. 2020, 5, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. The impact of corporate social capital on enterprise growth and its optimization—Based on the idea of social capital structuralism. Econ. Manag. 2013, 5, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, R.; Li, H.J. Research on the Influence of Co-benefit Orientation on social innovation of digital entrepreneurial enterprises. China Sci. Technol. Forum 2020, 11, 98–109. [Google Scholar]

- Sigfusson, T.; Chetty, S. Building international entrepreneurial virtual networks in cyberspace. J. World Bus. 2013, 48, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainela, T.; Puhakka, V.; Servais, P. The Concept of International Opportunity in International Entrepreneurship: A Review and a Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 3, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Classification | Sample Size | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 468 | 70.48% |

| Female | 196 | 29.52% | |

| Age | <30 | 292 | 43.98% |

| 31–40 | 215 | 32.38% | |

| 41–50 | 138 | 20.78% | |

| >51 | 19 | 2.86% | |

| Education background | Primary schools and below | 265 | 39.91% |

| Junior high school | 359 | 54.07% | |

| High school | 33 | 4.97% | |

| Bachelor and above | 7 | 1.05% | |

| Per-capita income level (year) | <5000 yuan | 206 | 31.02% |

| 5001–10,000 yuan | 164 | 24.70% | |

| 10,001–20,000 yuan | 252 | 37.95% | |

| >20,001 yuan | 42 | 6.33% | |

| Average time for migrant workers per year | <1 month | 176 | 26.50% |

| 1–3 months | 312 | 46.99% | |

| 3–6 months | 148 | 22.29% | |

| >6 months | 28 | 4.22% | |

| Broadband development levels | 1–6 M | 43 | 6.48% |

| 6–10 M | 80 | 12.05% | |

| 10–20 M | 62 | 9.34% | |

| >20 M | 468 | 70.48% | |

| Unable to answer | 11 | 1.66% | |

| County level of development | Poverty-stricken counties | 332 | 50.00% |

| Non-Poverty-stricken counties | 332 | 50.00% | |

| Family Background (Social Capital) | Relatively excellent | 363 | 54.67% |

| Relatively weak | 301 | 45.33% |

| Variable Name | Variable Measure | Factor Loading | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | Financial Literacy | 1. I have a good knowledge of passbook, bank card, credit card, online banking, bank protection or financial products, and gold business. | 0.707 |

| 2. I have a clear and accurate understanding of financial returns and financial risks. | 0.723 | ||

| 3. Every year, I plan the proportion of money I will spend on consumption, saving, or investment. | 0.850 | ||

| 4. I can adjust my savings plan for changes in interest rates. | 0.826 | ||

| 5. I can use a legal weapon to protect financial rights and interests. | 0.615 | ||

| Mediator | Financial Inclusion | 1. I feel that the number and types of financial institutions have increased in the past three years. | 0.632 |

| 2. It is more convenient for me to go to the financial institutions nearby. | 0.789 | ||

| 3. I think it’s easier to get bank approval for loans now. | 0.639 | ||

| 4. I think the interest rate is moderate, and we can afford it. | 0.741 | ||

| 5. My family has begun to attach importance to buying commercial insurance. | 0.798 | ||

| Moderator | Digital Literacy | 1. I can use network equipment well and work on the network. | 0.814 |

| 2. I know how to conduct network broadcasts and am familiar with e-commerce sales. | 0.888 | ||

| 3. I can enjoy the convenience brought by digitalization and enjoy it. | 0.889 | ||

| 4. I can make fair use of mobile phone APP, through which I have made many good friends and obtained a lot of resources, which was unimaginable before. | 0.574 | ||

| 5. I think the current network and smartphones are easy to operate and safe, and I can make all kinds of transactions with confidence. | 0.770 | ||

| Dependent variable | Digital entrepreneurial willingness and behavior | 1. I can use the digital platform to sell newly planted crops. | 0.774 |

| 2. I think I can sell my agricultural products at a good price through new methods such as live broadcasting and online sales, which can increase my income. | 0.676 | ||

| 3. For products with high risk but higher value, I prefer to plant or produce them because the sales can be guaranteed. | 0.854 | ||

| 4. Generally speaking, to make more money, I feel it is necessary to take risks to do something new because the big data environment has become more conducive to innovation. | 0.871 | ||

| 5. In the past five years, I have introduced new technologies to make the agricultural products or small handmade products different from the ones I sold before because I can sell them online. | 0.895 | ||

| 6. Through direct contact with consumers, my produce has created its own brand and generated more revenue. | 0.841 |

| Construct | Composite Reliability | Convergent Validity | Discriminant Validity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | AVE | FL | FI | DL | DE | |

| FL | 0.863 | 0.561 | 0.749 | |||

| FI | 0.845 | 0.523 | 0.636 | 0.723 | ||

| DL | 0.894 | 0.633 | 0.446 | 0.536 | 0.796 | |

| DE | 0.925 | 0.675 | 0.605 | 0.506 | 0.596 | 0.822 |

| Mean | S.E | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.295 | 0.456 | – | |||||||||

| 2. Age | 1.825 | 0.856 | 0.024 | – | ||||||||

| 3. Education | 1.672 | 0.619 | 0.045 | −0.285 ** | – | |||||||

| 4. Per capita income level | 2.804 | 0.952 | 0.008 | 0.656 ** | −0.155 ** | – | ||||||

| 5. Average time of migrant workers per year | 3.221 | 1.183 | 0.108 ** | 0.074 | −0.067 | 0.037 | – | |||||

| 6. Broadband development levels | 1.450 | 0.948 | −0.147 ** | 0.235 ** | 0.206 ** | 0.310 ** | −0.071 | – | ||||

| 7. FL | 1.502 | 0.649 | 0.014 | −0.074 | 0.104 ** | −0.071 | 0.015 | −0.016 | (0.854) | |||

| 8. FI | 2.194 | 0.782 | 0.027 | 0.008 | 0.041 | 0.084 * | −0.001 | −0.02 | 0.544 ** | (0.809) | ||

| 9. DL | 1.968 | 0.760 | 0.113 ** | −0.042 | 0.012 | −0.022 | 0.068 | −0.108 ** | 0.401 ** | 0.472 ** | (0.882) | |

| 10. DE | 1.469 | 0.588 | 0.046 | −0.101 ** | 0.127 ** | −0.080 * | 0.014 | 0.008 | 0.552 ** | 0.458 ** | 0.575 ** | (0.922) |

| Paths and Models | M1 | M2 | M3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FL→DE | FL→FI | FI→DE | ||

| Path Coefficient | FL→FI | 0.640 *** | ||

| FI→DE | 0.507 *** | |||

| FL→DE | 0.596 *** | |||

| Degree of Model Fit Indicators | X2/DF | 2.183 | 1.735 | 1.841 |

| CFI | 0.974 | 0.976 | 0.979 | |

| TLI | 0.970 | 0.972 | 0.975 | |

| RMSEA | 0.042 | 0.033 | 0.036 | |

| SRMR | 0.037 | 0.040 | 0.031 | |

| Path | Effect | Coefficient | S.E. | Z | Bootstrapping | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias-Corrected 95% CI | Percentile 95% CI | |||||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| M4: FL→FI→DE | Total effect | 0.597 *** | 0.056 | 10.721 | 0.484 | 0.698 | 0.477 | 0.695 |

| Indirect effect | 0.141 *** | 0.036 | 3.899 | 0.069 | 0.215 | 0.067 | 0.212 | |

| Direct effect | 0.456 *** | 0.076 | 6.019 | 0.305 | 0.603 | 0.297 | 0.595 | |

| Variable | DE Willingness and Behavior | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M5 | M6 | M7 | |

| Control variables | |||

| Gender | 0.044 | 0.002 | 0.010 |

| Age | −0.058 | −0.033 | −0.058 |

| Degree of education | 0.101 ** | 0.054 * | 0.044 |

| Per capita income level | −0.033 | −0.035 | −0.008 |

| Average time for migrant workers per year | 0.023 | −0.009 | −0.024 |

| Broadband development levels | 0.019 | 0.068 ** | 0.048 |

| Independent variable: FL | 0.370 *** | 0.303 *** | |

| Moderator variable: DL | 0.431 *** | 0.414 *** | |

| Interaction item: FL × DL | 0.198 *** | ||

| F | 2.687 | 71.467 | 72.181 |

| R2 | 0.024 | 0.466 | 0.498 |

| ∆R2 | 0.015 | 0.460 | 0.491 |

| Variable | DE Willingness and Behavior | Sense of FI | DE Willingness and Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| M8 | M9 | M10 | |

| Control variables | |||

| Gender | 0.013 | −0.032 | 0.016 |

| Age | −0.04 * | −0.025 | −0.037 |

| Degree of education | 0.041 | 0.018 | 0.040 |

| Per capita income level | −0.005 | 0.12 *** | −0.016 |

| Average time for migrant workers per year | −0.012 | −0.016 | −0.010 |

| Broadband development levels | 0.030 * | −0.015 | 0.031 * |

| Independent variable: FL | 0.275 *** | 0.555 *** | 0.228 *** |

| Moderator variable: DL | 0.320 *** | 0.318 *** | 0.290 *** |

| Interaction item: FL× DL | 0.146 *** | 0.088 *** | 0.145 ** |

| Mediating variable: sense of FI | 0.088 *** | ||

| Interaction item: FI × DL | 0.014 | ||

| F | 72.181 | 47.805 | 60.831 |

| R2 | 0.498 | 0.397 | 0.506 |

| ∆R2 | 0.491 | 0.389 | 0.498 |

| Model and Path | PSC (β) | NPSC (β) | Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| FL→FI | 0.644 *** | 0.537 *** | 0.107 ** |

| FI→DE | 0.556 *** | 0.707 *** | −0.151 ** |

| FL→DE | 0.531 *** | 0.460 *** | 0.071 * |

| FL→FI→DE | 0.137 *** | 0.124 *** | 0.013 ** |

| DL: Moderating effect | 0.427 *** | 0.781 *** | −0.354 ** |

| DL: Moderated-Mediating effect | 0.377 * | 0.724 *** | −0.347 ** |

| Model and Path | Family Background (Superior) High Level of Social Capital | Family Background (Inferior) Low Level of Social Capital | Comparison of Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| FL→DE | 0.649 *** | 0.550 *** | 0.099 ** |

| FL→FI | 0.682 *** | 0.607 *** | 0.075 * |

| FI→DE | 0.556 *** | 0.451 *** | 0.105 ** |

| FL→FI→DE | 0.162 *** | 0.117 *** | 0.045 ** |

| DL: Moderating effect | 0.555 *** | 0.678 *** | −0.123 ** |

| DL: Moderated-Mediating effect | 0.530 ** | 0.680 *** | −0.150 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, X.; Yu, M.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Q. How Does Financial Literacy Affect Digital Entrepreneurship Willingness and Behavior—Evidence from Chinese Villagers’ Participation in Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14103. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114103

Xiao X, Yu M, Liu H, Zhao Q. How Does Financial Literacy Affect Digital Entrepreneurship Willingness and Behavior—Evidence from Chinese Villagers’ Participation in Entrepreneurship. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14103. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114103

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Xiaohong, Mei Yu, Hai Liu, and Qing Zhao. 2022. "How Does Financial Literacy Affect Digital Entrepreneurship Willingness and Behavior—Evidence from Chinese Villagers’ Participation in Entrepreneurship" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14103. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114103