(Un)Heard Voices of Ecosystem Degradation: Stories from the Nexus of Settler-Colonialism and Slow Violence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Slow Violence and the Eco-Social Violence of Settler Colonialism

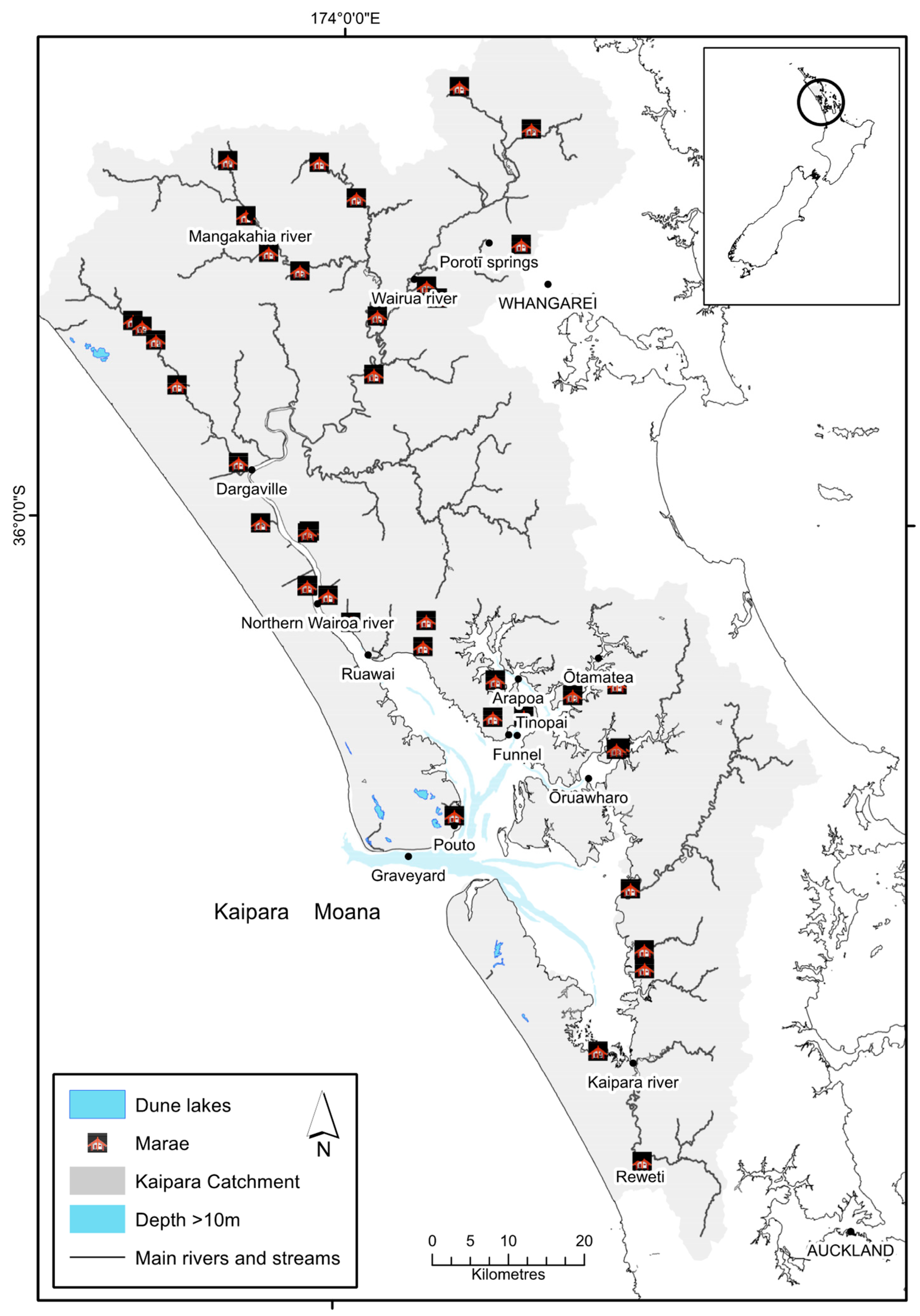

3. Kaipara Moana—A Seascape Enduring Slow Violence

4. Decolonising Methodology: “Thinking with Kaipara”

5. (Un)Heard Voices

5.1. Story: Why One Scallop

A young child asked me why is there only ONE scallop in Tinopai. To this, I replied, well,

ONE man bought land with a wetland in it and bulldozed the wetland, so the man next to him did the same and destroyed the other side of the wetland; Wetlands protect our Kaipara Moana.

ONE man has a pine forestry whose contractors felled their pines into our waterways, their machinery leached oil, their silt traps failed, and the tannins that came from the forestry went directly into our Kaipara Moana.

ONE man caught 1000 scallops in one day when the scallops were there only three years ago.

ONE farm directly above the scallop grounds sprayed poisons to kill the weeds and then sprayed his farm with nitrates and phosphates, all of which were washed into the Kaipara Moana when it rained the next day.

ONE farmer, all the way up the estuary, clear-felled his native trees down to the waterway, and you could follow the debris and mud trail all the way to the Kaipara Moana.

ONE mangrove forest was destroyed so that the beach would look better; mangroves prevent silt from entering our Kaipara Moana and are nurseries for fish.

ONE Council is millions of dollars in debt and does not have enough money to cope with the largeness of the Kaipara Moana.

ONE Regional Councillor is sitting in his office a hundred miles away. He is qualified in paperwork and argument but not in our Kaipara Moana.

ONE Kaipara Moana is so large that it has TWO Regional Councils that think differently.

ONE scientist found one scallop when he searched the whole of the Kaipara Moana, and that scallop was dying.

And when you put all of these men together and multiply them by the area of the Kaipara Moana—that is why there is only ONE SCALLOP IN TINOPAI.

Now that ONE SCALLOP can join our ‘no more’ list for Tinopai: No more mussels; no more scallops; together with our ‘barely there’ list: flounder, stingray, dolphins, orcas.

5.2. Story: Tuna Saved My Life

- Tena Koe.

Ko Whatitiri te maunga. E tu nei I te āo I te pō. Ko Waipao e Wairua te awa I rukuhia, I inumia e ōku mātua tupuna. Ko Maungarongo te marae. Hei tangi kit e hunga mate. Hei mihi kit e hunga ora. Ko Te Uriroroi. Ko Te Parawhau. Ko Te Māhurehure ki Whatitiri ngā hapū. Ko Ngāpuhi-Nui-Tonu te iwi. Ko Millan Ruka ahau.

You know your backyard when you haven’t moved out of it too often. Although I was born in Auckland, the Wairua and Mangakahia rivers are my turangawaewae.

Thirteen of my father’s brothers and sisters come from here, Porotī.

Born on the river…

A lot of them are buried… on the side of the river including my grandfather…

So that’s my place.

I can remember the days of the Wairoa and the Mangakahia rivers being crystal clear, and swimming in, and drinking from the river. You never thought twice to have a drink from the river…and streams. We’d sit on the bank of the river at home and just look down and spot an eel if you sat there long enough. Well, you couldn’t see anything. It’s… like a green soup…… They are nitrate laden. E.coli [bacteria] laden. Way past the drinkable stage, so taking your health into your own hands. Just seeing the depletion and the non-sustainability of the rivers,

just in my time….

Just a few metres on the other side of the bank. [Whole herd of cows] having a mimi everywhere. Excrement. Because they do that when they’re curious and just standing around, may as well have a crap while I’m here.

I started to cry.

Realising the enormity of it. This is unbelievable, knowing my rivers and even that place as a kid, and hard places to get to…

you won’t… see… the Wairua river unless you take a side road. So, you

don’t even… see … these rivers—the Wairoa, the northern Wairoa,

feeding into the Kaipara—you won’t… see … that until you get down to

Dargaville. So, you don’t… see … these rivers. You don’t… see …

what’s happening to them. Unless you’re … on… them.

The switch just went on…I’m going to report on… our rivers.

I couldn’t believe how much it had changed in a very short time because [of] the impact of dairying. Fonterra had evolved from being just a rural dairy companies to amalgamate into the huge giant they are now. Even in the [ten years] I was away, I saw many, many farms where it was one farmer just on the 220 acres or so, to being, that farmer had gone, or his son had taken over, and it amalgamated with the farm next door, left and right, to make it a bigger farm with 500 cows and 600 acres sort of thing. Intensification started there because they had big mortgages, but to me, they were relying on the capital gain as much as gain from the product. The intensification was huge. It was overnight.

- Millan thinks about the (slow and invisible) violent journey of disruption, degradation and manipulation the wai takes before it reaches the Kaipara moana. He explains te mana o te wai is denigrated, usurped, disconnected, and extracted. He describes his responsibility and obligation to protect the mauri of the Mangakahia and Wairua for current and future generations [69,70,71,72]. Te mana o te wai has not been protected or ensured, so Millan reports on the status of the awa, a responsibility as kaitiaki of the rivers. He creates GPS maps and photographs cattle stock movements, stock defecation and urination along the edges and in the awa. He submits the reports to the Council 0800 POLLUTION HOTLINE. His first report was in September 2011 on the Wairua power station canal. Sometimes reports include up to 140 photos that have GPS information attached. The report does not identify (landowner) names. It is not improving—the awa or the government response. Millan cannot drink and eat safely from the awa like he used to do as a young man. The physical devastation and degradation of his awa runs deep for Millan knowing that as a young man he could access and see the awa, drink from the awa, swim and get a feed of tuna from the awa; and financially support himself and his family. “Tuna saved my life,” Millan says. First, as a boy when his father returned, a WWII prisoner of war veteran and then as a man during the 1987–88 financial depression when no one needed a builder, just food. Evidence highlights that Indigenous peoples experience higher rates of personal trauma than Pākehā/Europeans/Whites and suffer a higher incidence of lifetime trauma [57]. The harm and grief Millan experiences from settler-colonialism is a daily embodiment, a characteristic of colonial ecological violence [12].

“We see ourselves after much study being the sentinels on the river for Ngāpuhi. One of my cousins pointed out we’ve always been a fighting line, Te Mahurehure. Where there are other hapū [that are] growers eh, harvesters of kaimoana or growers of food eh, gardens, but not us. Predominantly we’re just fighters.”

5.3. Story: We Survived off the Kaipara Moana

Ko wai toa te maunga Tokatoka. Ko wai to ate awa Wairoa. Ko wai toa te waka Mahuhukiterangi. Ko wai toa te iwi Ngāti Whātua. Ko wai toa te hapū Te Uri o Hau. Ko wai toa te marae Waiotea. Ko wai to ate moana Kaipara. Rangimarie Harris nee Connelly te mama, Guy Harris te papa. Glen Miru te tane.

Ko Vicky Miru ahau.

I’m passionate about the environment, and I care about the environment and worry about the environment, especially with my culture as Māori and when we gather kaimoana and things like that. I’ve noticed a lot of concerns about the moana and what’s been happening in the moana. That’s how I got involved. I got involved through Te Uri O Hau and Mikaera and a whole lot of other people that started this journey with them. We all had the same views and concerns and things to do with the moana and the environment. I just got involved because I care about it.

- Vicky talks about her life on the Kaipara moana and her kaitiakitanga responsibilities, which encapsulate an ethic for caring for Kaipara nature as well as all other more-than-humans who reside within the moana. Over the centuries and decades, the Kaipara, Vicky observes, provided Māori with so much kaimoana. However, the amount that can be harvested is becoming less and less. Vicky watched ongoing basis since first coming to Tinopai, to raise her children, over 30 years ago.

“What did you value about it?” Leane asks.

“There was plenty of kai,” Vicky responds.

AND,

AND

AND

AND

“Quite a few warning bells were going, that this isn’t right,” Leane says.

AND

AND

“So, you, the whānau, put the rāhui down?” Leane asks.

“Yes,” Vicky responds.

AND

“That was quite significant, wasn’t it?” Leane says.

“It was. Yeah. It worked.” Vicky responds.

AND

“No,” Vicky responds.

AND

AND

AND

AND

AND

5.4. Story: Section Five [of the RMA]: “This Is Bullshit”

“[I] pull out a gun and fire a bullet and now everyone is listening,”

“This is a bullshit society.”

The (Pāhēka) Law [Fisheries Act 1996] then assisted the community of Tinopai and Kaipara with a two-year closure.

“We were starving right [here] on the shore.” Mikaera continues,

“This kōrero is so huge and large that you can not talk about it in one session.”

There is corruption at play; exclusion and racism he says.

“[It’s] another manifestation of institutional racism,” says Mikaera.

5.5. Story: Te Aō Māori, Te Aō Pākehā—I’ve Been Brought Up in Both Worlds

Ka tangi te titi, ka tangi te kaka, ka tangi hoki ahau, tihei mauri ora. E tū ana au ki te taumata o Muarangi e tū takoto rā. Ka titiro whakararo iho ki te iwi o Ngāti Whatua. I te waka o Mahuhu ki te rangi. E rere nei I ngā wai karekare o Kaipara. Ka ū te waka ki uta, ki te marae nukunuku-ātea o Waikaretu. Kia rongo I te reo pōhiri o Te Uri o Hau. E mihi nei, e karanga nei. Ko Alyssce Te Huna ahau.

The colonisation of Māori saddens me.

The jealousy, deceit, nepotism and standing,

on each other, to get to the top must stop.

The constant need to educate nonMāori staff

in te ao Māori is tiring and a waste of my oxygen.

It is never used in the way it should be.

They pay ‘other’ experts hundreds of dollars but nothing for the mātauranga I hold.

My wairua is not nourished, nor whole.

I feel conflicted, unsafe, unheard, unsettled, lost,

disrespected, judged, excluded, marginalised,

and even frightened.

Racism and jealousy are rife.

I am not an administrator,

I am not a secretary or a Māori advisor.

I am a wahine Māori, a wife, a mother, a daughter,

A warrior seeded and pollinated by my te uri o hau grandmother.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Glossary | Many translations sourced from https://māoridictionary.co.nz/, accessed on 1 January 2020. This website provides audio for the kupu/words. |

| Ahi kā | Burning fires of occupation |

| Aotearoa | Māori name for New Zealand |

| Aroha | To love, feel concern, affection |

| Awa | Waterway, river, stream |

| Hauora | Be fit, well, healthy, vigorous and in good spirits |

| Iwi | Tribal group |

| Kai | Food |

| Kaimahi | Worker, practitioner |

| Kai moana | Seafood, shellfish |

| Kaitiakitanga/kaitiaki | A social-environmental ethic that promotes a use agreement with natural ecosystems whereby an inter-generational and sustainable relationship between people and the ecosystem is retained within a customary area [95] (Kawharu. It is a contemporary “nurture and care” responsibility [85] which has intensified in response to the loss of biodiversity and the ecosystem degradation of ancestral land- and sea-scapes. A key imperative of kaitiakitanga is maintaining values of whakapapa, mana and mauri, health and vitality of ecosystems to protect their life-supporting properties. This role is performed by kaitiaki “a guardian, keeper, preserver, conservator, foster-parent, protector” [37] of places and things for the gods, and kaitiaki may not necessarily or are assumed to, take a human form. Kaitiakitanga is a practice that upholds tikanga [96] and has implications for health and wellbeing. Kaitiakitanga is political and concerned with Indigenous rights. |

| Kanohi ki te kanohi | Face to face |

| Karakia | prayer |

| Kaumatua | Adult, elderly man/woman, elder |

| Kaupapa | Project, programme, theme, issue, plan, matter for discussion |

| Kaupapa Māori | Is privileging Māori ontologies, knowledges and practices to research, learning, planning, health and language. In the research sector, includes the critique of colonialism and adversity alongside Māori agency and aspirations. Simply, means a Māori way of doing things; Māori approach, Māori agenda, Māori principles. |

| Kōtiro | Daughter, girl |

| Mahi | Work |

| Mahinga kai | Food gathering place |

| Mana | Prestige, authority, power, influence, status, spiritual power, charisma—mana is a supernatural force in a person, place or object. Mana goes hand in hand with tapu, one affecting the other. The more prestigious the event, person or object, the more it is surrounded by tapu and mana. |

| Mana whenua | Authority over tribal land or territory |

| Manaakitanga/manaaki | hospitality, reciprocity |

| Māori | Aboriginal inhabitant, Indigenous person, native |

| Marae | Courtyard in front of wharenui (meeting house) where formal greetings and discussions take place. Often used to include the complex of buildings around the marae. |

| Mātauranga | Indigenous wisdom, knowledge, knowing being and doing. Is philosophy, knowledge, method, values and language |

| Mate | Sick, ailing, unwell, diseased, be dead |

| Mauri | Life principle, internal energy or vital essence, source of emotions; derived from whakapapa, an essential essence or element sustaining all forms of life. Is the binding force that links the physical to the spiritual worlds (e.g., wairua). |

| Mihimihi | Greeting, formal speech, thank, pay tribute |

| Mimi | To urinate |

| Moana | Sea, ocean, coast, saltwaters |

| Pākehā | New Zealander of European descent |

| Papatūānuku | Primal parent, mother earth |

| Rahui | Restrictions on access and use of certain resources |

| Rohe | Tribal land, waters and area |

| Te ao Māori | Māori ontology |

| Taonga | Treasure |

| Tapu | Sacred |

| Tuna | Eel. The longfin eel, Anguilla dieffenbachi, (conservation status: endangered) are diminishing from loss of habitat, and suitable water quality and lack of suitable access for kaitiaki to manaaki tuna [97]. |

| Te taiao | Ecosystem, environment, nature |

| Tikanga | Māori lore/law, correct procedure, custom, practice |

| Turangawaewae | Standing, place where one has the right to stand, place where one has rights of residence and belonging through kinship and whakapapa |

| Wāhi tapu | Forbidden, sacred |

| Wahine | Female essence |

| Wai | Water, stream, creek, tears |

| Wairua | Spirit, spirituality |

| Waka | Canoe, vehicle, traditional Māori canoe |

| Whakapapa | Genealogy |

| Whenua | Land, placenta |

References

- Cahill, C.; Pain, R. Representing Slow Violence and Resistance: On Hiding and Seeing. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2019, 18, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Spivak, G. Can the Subaltern Speak? In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture; Nelson, C., Grossberg, L., Eds.; Macmillan Education: Basingstoke, UK, 1988; pp. 271–313. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, K. Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice. Environ. Soc. 2018, 9, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parsons, M.; Fisher, K.; Crease, R.P. Decolonising Blue Spaces in the Anthropocene: Freshwater Management in Aotearoa New Zealand; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, C.; Lawrence, R. Accumulating Minerals and Dispossessing Indigenous Australians: Native Title Recognition as Settler-Colonialism. Antipode 2019, 51, 818–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veracini, L. Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-230-29919-1. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, K. Indigenous Climate Change Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene. Engl. Lang. Notes 2017, 55, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, J. Indigenous Resistance, Planetary Dystopia, and the Politics of Environmental Justice. Null 2021, 18, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilio-Whitaker, D. As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice from Colonization to Standing Rock; Beacon Press: Boston, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck, E.; Yang, K.W. Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor. Decolonization Indig. Educ. Soc. 2012, 1, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, V. Indigenous Place-Thought and Agency Amongst Humans and Non Humans (First Woman and Sky Woman Go on a European World Tour!). Decolonization Indig. Educ. Soc. 2013, 2, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, J. Settler Colonialism as Eco-Social Structure and the Production of Colonial Ecological Violence. Environ. Sociol. 2019, 5, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guernsey, P.J. The Infrastructures of White Settler Perception: A Political Phenomenology of Colonialism, Genocide, Ecocide, and Emergency. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2022, 5, 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, U.; Enelow, S. Research Theatre, Climate Change, and the Ecocide Project: A Casebook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, D. Environmental Genocide. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 1998, 57, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-877578-28-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, W.A.; O’Brien, K.J. Environmental Ethics and Uncertainty: Wrestling with Wicked Problems; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, A.; Patel, Z.; Greyling, S. Tackling Wicked Problems and Tricky Transitions: Change and Continuity in Cape Town’s Environmental Policy Landscape. Null 2016, 21, 1063–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, J.M. Dangerous Pipelines, Dangerous People: Colonial Ecological Violence and Media Framing of Threat in the Dakota Access Pipeline Conflict. Null 2020, 6, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N. Dying to Eat? Black Food Geographies of Slow Violence and Resilience. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2019, 18, 1076–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, R. Slow Violence, Gender, and the Environmentalism of the Poor. In Environment at the Margins; Caminero-Santangelo, B., Myers, G., Eds.; Ohio University Press: Athens, Greece, 2011; pp. 257–285. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, T. Slow Violence and Toxic Geographies: ‘Out of Sight’ to Whom? Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2022, 40, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Nalau, J. Historical Analogies as Tools in Understanding Transformation. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 38, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.J. Deathscapes of Settler Colonialism: The Necro-Settlement of Stoney Creek, Ontario, Canada. Null 2018, 108, 1134–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whyte, K.P. Our Ancestors’ Dystopia Now: Indigenous Conservation and the Anthropocene. In The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities; Ursula, H., Jon, C., Michelle, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, H.; Todd, Z. On the Importance of a Date, or Decolonizing the Anthropocene. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2017, 16, 761–780. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, J.M.; Dowler, L. Slow and Fast Violence: A Feminist Critique of Binaries. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2019, 18, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Folkers, A. Fossil Modernity: The Materiality of Acceleration, Slow Violence, and Ecological Futures. Time Soc. 2021, 30, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Lear, S. Climate Science and Slow Violence: A View from Political Geography and STS on Mobilizing Technoscientific Ontologies of Climate Change. Political Geogr. 2016, 52, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottinger, G. Making Sense of Citizen Science: Stories as a Hermeneutic Resource. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, D. Indigenous Environmental Justice, Knowledge, and Law. Kalfou A J. Comp. Relat. Ethn. Stud. 2018, 5, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.; Green, D.; Sullivan, M.; Cohen, D. Environmental Justice Analyses May Hide Inequalities in Indigenous People’s Exposure to Lead in Mount Isa, Queensland. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 084004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasic, E.; Armstrong, D. Ngāti Whātua: An Overview History; Te Runanga o Ngāti Whātua: Auckland, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, G. Mahuhu: The ancestral canoe of Ngati Whatua (Kaipara). J. Polyn. Soc. 1939, 48, 186–191. [Google Scholar]

- Pihema, A. The History of Ngāti Whātua; Ani Pihema: Auckland, New Zealand, 1960.

- Mead, H.M. Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori Values; Huia (NZ) Ltd.: Wellington, New Zealand, 2006; ISBN 978-1-77550-074-2. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, M.; Royal, T.A.C. The Woven Universe: Selected Writings of Rev. Māori Marsden; Estate of Rev. Māori Marsden: Whangarei, New Zealand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mahuika, N. A Brief History of Whakapapa: Māori Approaches to Genealogy. Genealogy 2019, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mead, H.M. Ngā Pēpeha A Ngā Tīpuna = The Sayings of the Ancestors/nā Hirini Moko Mead Rāua ko Neil Grove; Victoria University Press: Wellington, New Zealand, 2001; ISBN 0-86473-399-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brougham, A.E. The Raupō Book of Māori Proverbs, 5th ed.; Raupo: Auckland, New Zealand, 2012; ISBN 978-0-14-356791-2. [Google Scholar]

- Whaanga, H.; Wehi, P.; Cox, M.; Roa, T.; Kusabs, I. Māori Oral Traditions Record and Convey Indigenous Knowledge of Marine and Freshwater Resources. Null 2018, 52, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Fisher, K. Indigenous Peoples and Transformations in Freshwater Governance and Management. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 44, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsworth, G.; Awatere, S.; Robb, M. Indigenous Māori Values and Perspectives to Inform Freshwater Management in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hikuroa, D.; Slade, A.; Gravley, D. Implementing Māori Indigenous Knowledge (Mātauranga) in a Scientific Paradigm: Restoring the Mauri to Te Kete Poutama. MAI Rev. 2013, 3, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Fawcett, M.; Ruru, J.; Tipa, G. Indigenous Resource Management Plans: Transporting Non-Indigenous People into the Indigenous World. Plan. Pract. Res. 2017, 32, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikuroa, D.; Brierley, G.; Tadaki, M.; Blue, B.; Salmond, A. Restoring Sociocultural Relationships with Rivers. In River Restoration; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 66–88. ISBN 978-1-119-41001-0. [Google Scholar]

- Waitangi Tribunal. The Kaipara Report: WAI 674; Waitangi Tribunal: Wellington, New Zealand, 2006.

- Anderson, A.G.; Moran, W. Land Use Change in Northland. Part One: Dairy Farming in the 1970s. A Review; Occasional Paper No. 12; Geography Department, University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics New Zealand. Agricultural Production Statistics: June 2017 (Final); Statistics New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2017.

- Statistics New Zealand. Agricultural Fertilisers—Nitrogen and Phosphorus: April 2021 (Final); Statistics New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021.

- Ministry for the Environment; Statistics New Zealand. New Zealands Environmental Reporting Series. Our Land 2021; Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021.

- McLay, C.L. An Inventory of the Status and Origin of New Zealand Estuarine Systems. Proc. N. Z. Ecol. Soc. 1976, 23, 8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Makey, L. ‘Thinking with Kaipara’: A Decolonising Methodological Strategy to Illuminate Social Heterogenous Nature–Culture Relations in Place. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2021, 5, 1466–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makey, L.; Fisher, K.; Parsons, M.; Bennett, A.; Miru, V.; Morehu, T.K.-I.; Sherard, J. Lived Experiences at the Intersection of Sediment(ation) Pollution, Gender, Ethnicity and Ecosystem Restoration from the Kaipara Moana, Aotearoa New Zealand. GeoHumanities 2021, 8, 197–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makey, L.; Awatere, S. He Mahere Pāhekoheko Mō Kaipara Moana–Integrated Ecosystem-Based Management for Kaipara Harbour, Aotearoa New Zealand. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2018, 31, 1400–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataria, J.; Mark-Shadbolt, M.; Mead, A.T.P.; Prime, K.; Doherty, J.; Waiwai, J.; Ashby, T.; Lambert, S.; Garner, G.O. Whakamanahia Te Mātauranga o Te Māori: Empowering Māori Knowledge to Support Aotearoa’s Aquatic Biological Heritage. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2018, 52, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihama, L.; Reynolds, P.; Smith, C.; Reid, J.; Smith, L.T.; Te Nana, R. Positioning Historical Trauma Theory within Aotearoa New Zealand. AlterNative 2014, 10, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, S. Intimate Colonialisms: The Material and Experienced Places of British Columbia’s Residential Schools. Can. Geogr. 2007, 51, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D. The Biopolitics of Postmodern Bodies: Determinations of Self in Immune System Discourse. In Feminist Theory and the Body: A Reader; Price, J., Shildrick, M., Eds.; Edinburgh UP: Edinburgh, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw, S.; Parkes, M.W.; Morgan, V.S.; Christensen, J.; Lindsay, N.; Mitchell-Foster, K.; Russell Jozkow, J. Going Unscripted: A Call to Critically Engage Storytelling Methods and Methodologies in Geography and the Medical-Health Sciences. Can. Geogr. Le Géographe Can. 2017, 61, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Leeuw, S.; Cameron, E.S.; Greenwood, M.L. Participatory and Community-Based Research, Indigenous Geographies, and the Spaces of Friendship: A Critical Engagement. Can. Geogr. Le Géographe Can. 2012, 56, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.; Lloyd, K.; Suchet-Pearson, S.; Burrawanga, L.; Tofa, M.; Country, B. Telling Stories in, through and with Country: Engaging with Indigenous and More-than-Human Methodologies at Bawaka, NE Australia. J. Cult. Geogr. 2012, 29, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.C.; Johnson, J.T. The Agency of Place: Toward a More-Than-Human Geographical Self. Null 2016, 2, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, F.; Breheny, M.; Forster, M. Kaupapa Kōrero: A Māori Cultural Approach to Narrative Inquiry. AlterNative 2018, 14, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Country, B.; Wright, S.; Suchet-Pearson, S.; Lloyd, K.; Burarrwanga, L.; Ganambarr, R.; Ganambarr-Stubbs, M.; Ganambarr, B.; Maymuru, D.; Sweeney, J. Co-Becoming Bawaka: Towards a Relational Understanding of Place/Space. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 40, 455–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Country, B.; Wright, S.; Suchet-Pearson, S.; Lloyd, K.; Burarrwanga, L.; Ganambarr, R.; Ganambarr-Stubbs, M.; Ganambarr, B.; Maymuru, D. Working with and Learning from Country: Decentring Human Author-Ity. Cult. Geogr. 2015, 22, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLure, M. Researching without Representation? Language and Materiality in Post-Qualitative Methodology. Null 2013, 26, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, T.K.; Jones, A. Non-Human Others and Kaupapa Māori Research. In Critical Conversations in Kaupapa Māori; Hoskins, T.K., Jones, A., Eds.; Huia Ltd.: Wellington, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Whatitiri Resource Managment Unit. Whatitiri Resource Management Plan; Whatitiri Resource Management Unit: Whangarei, New Zealand, 2013.

- Nga Kaitiaki o Ngā Wai Māori. Ngā Kaitiaki o Ngā Wai Māori Strategic Plan. 2012–2016; Ngā Kaitiaki o Ngā Wai Māori: Whangarei, New Zealand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, D.H.; Munro, T.; Carter, M.; Norris, L.; Nathan, R. Whatitiri: “The Lands, the Peoples and Their Water”. Report Prepared for Te Paparahi o Te Raki Inquiry Wai 1040; Waitangi Tribunal: Wellington, New Zealand, 2012.

- Māori, K.W. Te Mana o Te Wai. The Health of Our Wai, The Health of Our Nation. Kāhui Wai Māori Report to Hon Minister David Parker; Kāhui Wai Māori: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019.

- Hamer, P. Porotī Springs and the Resource Management Act, 1991–2015. A Report Commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal for the Te Paparahi o e Raki Inquiry. WAI1040; Waitangi Tribunal: Wellington, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Salmond, A. Ontological Quarrels: Indigeneity, Exclusion and Citizenship in a Relational World. Anthropol. Theory 2012, 12, 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantzler, J.M. Environmental Justice as Decolonization: Political Contention, Innovation and Resistance Over Indigenous Fishing Rights in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, P.; Kirk, N. Role of Indigenous Māori People in Collaborative Water Governance in Aotearoa/New Zealand. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2012, 55, 941–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodwitch, H.; Song, A.M.; Temby, O.; Reid, J.; Bailey, M.; Hickey, G.M. Why New Zealand’s Indigenous Reconciliation Process Has Failed to Empower Māori Fishers: Distributional, Procedural, and Recognition-Based Injustices. World Dev. 2022, 157, 105894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, G. Red Skin, White Masks Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, F. The Reconstitution of Property Relations in New Zealand Fisheries. Anthropol. Q. 2012, 85, 171–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, F. Sustainability in New Zealand’s Quota Management System: A Convenient Story. Mar. Policy 2017, 80, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersoug, B. “After All These Years”—New Zealand’s Quota Management System at the Crossroads. Mar. Policy 2018, 92, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitangi Tribunal. Report of the Waitangi Tribunal on the Muriwhenua Fishing Claim. WAI 22; Waitangi Tribunal: Wellington, New Zealand, 1988.

- Barclay, B.; Selwyn, D. The Kaipara Affair; He Taonga Films: Auckland, New Zealand, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Waitangi Tribunal. The Stage Two Report on the National Freshwater and Geothermal Resources Claims. Wai 2358; Waitangi Tribunal: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019; p. 618.

- Waitangi Tribunal. Ko Aotearoa Tēnei. Te Taumata Tuatahi. A Report into Claims Concerning New Zealand Law and Policy Affecting Māori Culture and Identity. Wai 262; Waitangi Tribunal: Wellington, New Zealand, 2011.

- Resource Management Review Panel. New Directions for Resource Management in New Zealand. Report of the Resource Management Review Panel; Resource Management Review Panel: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020.

- Tomlins-Jahnke, H. Whaia Te Iti Kahurangi: Contemporary Perspectives of Māori Women Educators; Massey University: Auckland, New Zealand, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- De Leeuw, S. Tender Grounds: Intimate Visceral Violence and British Columbia’s Colonial Geographies. Political Geogr. 2016, 52, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, A. The Nature of Gender: Work, Gender, and Environment. Environ. Plan. D 2006, 24, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waitangi Tribunal. Hauora. Report on Stage One of the Health Services and Outcomes Kaupapa Inquiry. Pre-Publication Version. WAI 2575; Waitangi Tribunal: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019.

- Harris, R.B.; Stanley, J.; Cormack, D.M. Racism and Health in New Zealand: Prevalence over Time and Associations between Recent Experience of Racism and Health and Wellbeing Measures Using National Survey Data. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, R.; Moewaka-Barnes, H.; McCreanor, T. Placing Racism in Public Health: A Perspective from Aotearoa/New Zealand. GeoJournal 2009, 74, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, H.M. Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori Values; Huia (NZ) Ltd.: Wellington, New Zealand, 2003; ISBN 9781877283888. [Google Scholar]

- Bodwitch, H. Challenges for New Zealand’s individual transferable quota system: Processor consolidation, fisher exclusion, & Māori quota rights. Mar. Policy 2017, 80, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kawharu, M. Kaitiakitanga: A Māori anthropological perspective of the Māori socio-environmental ethic of resource management. J. Polyn. Soc. 2000, 109, 349–370. [Google Scholar]

- Selby, R.; Moore, P.; Mulholland, M.; Wananga-o-Raukawa, T. Māori and the Environment: Kaitiaki; Huia: Wellington, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- PCE. On a Pathway to Extinction? An Investigation into the Status and Management of the Longfin Eel; Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment: Wellington, New Zealand, 2013; p. 95.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makey, L.; Parsons, M.; Fisher, K.; Te Huna, A.; Henare, M.; Miru, V.; Ruka, M.; Miru, M. (Un)Heard Voices of Ecosystem Degradation: Stories from the Nexus of Settler-Colonialism and Slow Violence. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214672

Makey L, Parsons M, Fisher K, Te Huna A, Henare M, Miru V, Ruka M, Miru M. (Un)Heard Voices of Ecosystem Degradation: Stories from the Nexus of Settler-Colonialism and Slow Violence. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):14672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214672

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakey, Leane, Meg Parsons, Karen Fisher, Alyssce Te Huna, Mina Henare, Vicky Miru, Millan Ruka, and Mikaera Miru. 2022. "(Un)Heard Voices of Ecosystem Degradation: Stories from the Nexus of Settler-Colonialism and Slow Violence" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 14672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214672

APA StyleMakey, L., Parsons, M., Fisher, K., Te Huna, A., Henare, M., Miru, V., Ruka, M., & Miru, M. (2022). (Un)Heard Voices of Ecosystem Degradation: Stories from the Nexus of Settler-Colonialism and Slow Violence. Sustainability, 14(22), 14672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214672