1. Introduction

China is proposing a dual circulation economic development strategy to cope with the complexity of global economic, political, cultural, and security issues by relying mainly on the domestic sector and bolstering the international sector [

1]. This new dual circulation model combines domestic and international double circulation with a key role in the international sector. Foreign investment and global trade have therefore become increasingly important to China. For instance, local governments in the Yangtze River Economic Belt actively assist small and medium foreign trade enterprises affected by the epidemic by reducing taxes and rent costs and subsidizing operating costs [

2].

The prior literature focused on traditional financial risks when it came to foreign direct investment (FDI) in China. However, the domestic market in China has changed in recent years. A rise in labour costs and the evolution of digitalization has challenged the traditional enterprise operating model. In digital transformations, manufacturing resources are reorganized and value is created for customers by connecting digital technology and traditional production methods [

3]. The COVID-19 shock led to new businesses adopting online sales systems and electronic information systems, as well as moving their operations online [

4]. In addition to the negative impact of COVID on the economy and the Sino–US trade war, the Russia–Ukraine war and other events make the international situation more complex. The main risk factors faced by transnational enterprises in China are different from those in the past. The existing literature on the risk perception of FDI in China under the changing situation needs to be updated urgently. Moreover, there is a paucity of research on the current management performance of various risks and the priority of risk management in the future. This study fills the gap in the research on risk identification and risk management of FDI in China. It provides a reference for foreign SMEs to make investment or divestment decisions.

The Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China and the Forward Industry Research Institute have proposed that China has seen the largest amount of FDI withdrawal from South Korea, Japan, and the United States during the epidemic. A total of USD 1.92 billion, USD 350 million, and USD 380 million of FDI were withdrawn from South Korea, Japan, and the United States in 2020, respectively. FDI will recover in 2021, but it will change. Moreover, multinational enterprises are withdrawing capital mainly from Guangdong, Shanghai, and Jiangsu. During 2020–2021, Guangdong Province deregistered 1274 foreign-funded enterprises with a disinvestment of USD 4.22 billion dollars; 2649 foreign-funded enterprises were written off in Shanghai Province, with a disinvestment of USD 4.32 billion, and 1027 of those enterprises were written off in Jiangsu Province, with disinvestment of USD 5.33 billion. This study examines Korean, Japanese, and American multinational corporations to reflect the disinvestment of foreign-funded enterprises primarily from the aforementioned Chinese cities. Therefore, we need to pay attention to enterprise risk management (ERM) or risk management (RM) of foreign-funded enterprises to make multinational enterprises more adaptable to the local Chinese environment. FDI should be managed differently depending on its goal or type, whether it seeks to gain resources, market shares, or efficiency. Does FDI risk appraisal differ based on the nature or goal of the investment? From a theoretical perspective, it is pretty apparent that the answer to question one is: ‘yes’. We attempt to answer the second question by examining FDIs in China.

It is important to manage the risks associated with FDI in a reasonable manner, given the multitude of FDI objectives [

5,

6]. Managing risk should, for instance, focus on protecting the organization’s most important long-term goals. Business structures and industry affiliations can endogenously determine the type and style of FDI risk. Gaffney [

7] and Kinuthia and Murshed [

8] list labour management as one of the most significant concerns in RM of capital-intensive businesses entering low-cost labour markets. Another option would be to seek a low-labour-cost country and manage the risk associated with ORs. To reduce ambiguities arising from the differences between countries, it is prudent to check the rationality or effectiveness of FDI RM in an identical country.

China’s ongoing economic growth has made it a high-income market rather than a low-cost one, making it a suitable location for FDI. China is only a distribution region for some foreign companies, whereas others view the country as a leading business hub [

9]. Several affirmative policies for foreign companies were cancelled following 2003, as Chinese authorities switched to a policy that emphasized qualitative growth rather than quantitative development. In China, the introduction of the revised Labor Act resulted in a rise in wage rates [

10]. As a result, foreign companies experienced economic difficulties as the investment climate in China changed, resulting in divestitures of Chinese markets, moving production facilities to Southeast Asia, or simply thinking about the Chinese market as another outlet for foreign goods sold.

The OLI (ownership, location, internalization) theory proposes that location advantage determines the flow of international investment. However, different FDI motivations have different considerations for location advantages and the evaluation of the investment environment. Therefore, FDI motivations can be divided into market, efficiency, resources, and strategic asset-seeking [

11]. A systematic risk management system for international enterprises was developed by COSO [

12], which presents a concept of detailed circular processes for risk management, such as risk awareness, risk element analysis, risk control (avoidance, management, transfer, mitigation), and risk management performance evaluation. According to Agarwal, risk response and management can be divided into four main components, including strategic risk (SR) (such as economic environment, policy environment, population change, competition); financial risk (FR) (such as market risk, credit risk, price risk, liquidity risk); operational risk (OR) (such as human error, computer operation error, decision-making error, management process error); and hazard risk (HR) (such as property, regulations, individuals, breach of contract, etc.). Insurance can solve hazard risk, whereas strategic measures are needed to control the other three risks [

13].

This study follows this framework and classifies risks into quadrants: FR, SR, HR, and OR. OR reflects a mismatch of internal operating procedures with standard requirements. However, despite having a wider range of risks than marketing risk, SR is a lot like marketing risk. HR arises when a wide range of variables, such as inflation, exchange rates, asset values, liabilities, revenues, or expenses, are subject to changes. FR includes changes in lending, forex, and equity prices [

13,

14]. A major goal of this study is to determine whether FDIs manage their risks differently in China and whether their RM is efficient. However, since this study only examines foreign enterprises in China, we classify corporate risks into only four categories. Doing this allows RM activities to be incorporated into operation activities without losing generality. According to Gaffney [

7] and Razzaq et al. [

15], efficiency and market-seeking FDIs focus clearly on different risks and are more effective at minimizing them.

In the current literature, integrated risk management is rarely discussed [

16]. This study elaborates and analyses the risk quadrant perception [

9] and COSO risk corresponding processes in terms of related risk management concepts [

12]. Moreover, this paper uses a questionnaire survey and professional consultation to gather “risk perception” material and analyze the data in order to overcome the bottleneck caused by financial statements and panel data. Hence, this paper represents a novel attempt at these aspects. This study examined the risk factors of smaller foreign manufacturing enterprises in China. The survey was designed to determine how they manage risks and to evaluate how it affects performance. Considering their investment objectives, we divided foreign SMEs into two types, i.e., market- and efficiency-seeking. Five main sections make up this study:

Section 1 introduces the study and provides a summary of its context and objectives;

Section 2 summarizes and describes risks associated with management, direct investment, and performance and determines factors associated with risk. It also determines factors that should be included in an RM plan;

Section 3 presents theoretical concepts and hypotheses for the study are formulated; and

Section 4 details empirical research on RM for direct investments. A conclusion is provided in the last section,

Section 5.

3. Hypothesis and Analytical Model

This section presents the theoretical background and formulation of the hypothesis.

3.1. Hypothesis

Following is the detail of the research hypothesis.

3.1.1. Risk Factors and Risk Management: A Correlation

Step one is to correlate the risk control of Chinese foreign-owned companies with the risk aspects involved. Here, RM is evaluated to determine whether it affects performance directly or indirectly and whether performance satisfaction can be improved through RM. Through RM, the second step is to identify if there is a difference in performance risk factors based on investment motives. As part of the management of risks, subsidiaries carry out localization [

51,

52], increase customer loyalty, strengthen the brand names, develop strong relationships with local companies, and transfer technology to subsidiaries when they face risks such as capital costs, regulatory issues, competitive problems, and management concerns [

15,

53,

54]. When facing market competition risk and environmental uncertainty risk, Porter and Miller [

55,

56] suggested that foreign investment companies can reduce costs, differentiate, and centralize. According to Saeidi et al. [

57], enterprises manage risks better when they increase in size due to their increased risk levels. As Cooke et al. [

58] discovered, foreign-owned manufacturing companies in China can manage their risks if the macro-environmental uncertainty increases using a commitment-based human resource system. It has been observed by Shad et al. [

49] that business activity and social risk have a positive effect on RM.

Hypothesis 1. There is a significant impact of risk factors on performance.

3.1.2. Risk Factors and Risk Performance: A Correlation

The second step is to correlate risk factors with management performance. Business performance was influenced more by external factors than by internal factors. A company’s performance will be adversely affected more as a result of political risk, competitive risk, technological lag, and scanty knowledge about the domestic industry. Many studies show that a company’s financial standing negatively influences performance in a foreign country [

38,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. Investment performance is negatively affected by increasing institutional and legal concerns of enterprises doing business in China and uncertain market conditions [

37,

42,

65].

Hypothesis 2. There is a significant impact of RM on performance.

3.1.3. Risk Management and Risk Performance: A Correlation

The third step is to examine the correlation between RM and performance. A study by Olson and Wu [

66] indicates a positive impact on business performance can be achieved by strengthening business strategy, leadership skills, and organizational management. An effective HR system and authority given to the local subsidiary can positively impact performance, according to Cooke et al.’s [

58] study. Several ways have been proven effective in promoting the performance of foreign-owned direct investment enterprises in China. It may include localizing production, and marketing capabilities, promoting research and development abilities, diversification, improving technology innovation abilities, developing local human resource development, establishing joint ventures with local partners, strengthening domestic sales organizations, improving strategy, scaling up finances, and following local laws [

9,

39,

61,

64,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72].

Hypothesis 3. According to the type of investment motive (efficiency-seeking and market-seeking), risk factors would have significantly different correlations with RM and performance.

3.1.4. Mediating Effects of Investment Motives

Several factors contribute to foreign enterprises’ investments in international markets. According to Almfraji and Almsafir [

6] and Dunning [

30], there are three significant motives: seeking market opportunities, resources, and efficiency. FDI’s motivation (market-seeking or efficiency-seeking) affects the firm’s strategy or RM and performance [

15]. FDI motivations include market, efficiency, resources, and strategic assets-seeking approaches [

11]. Based on this study about China, market-seeking and efficiency-seeking motivations are deemed to be more acceptable. Market-seeking motivation is to avoid trade barriers and expand the market in the host country, whereas efficiency-seeking motivation is to obtain abundant and low-cost labour in that country. Companies seeking market share would not withdraw subcontractors or give up business from a large company. However, efficiency-seeking companies would withdraw operations from China or reverse their decision to return to foreign operations because tariffs on these components can increase production costs [

73,

74]. It has also been found that those businesses that pursued differentiation strategies (strengthening brands, quality, and customer service) had the most significant impact. It turned out that performance and productivity were more positively affected for those who adopted a cost advantage strategy than those who employed a cost advantage strategy.

3.2. Analytical Model

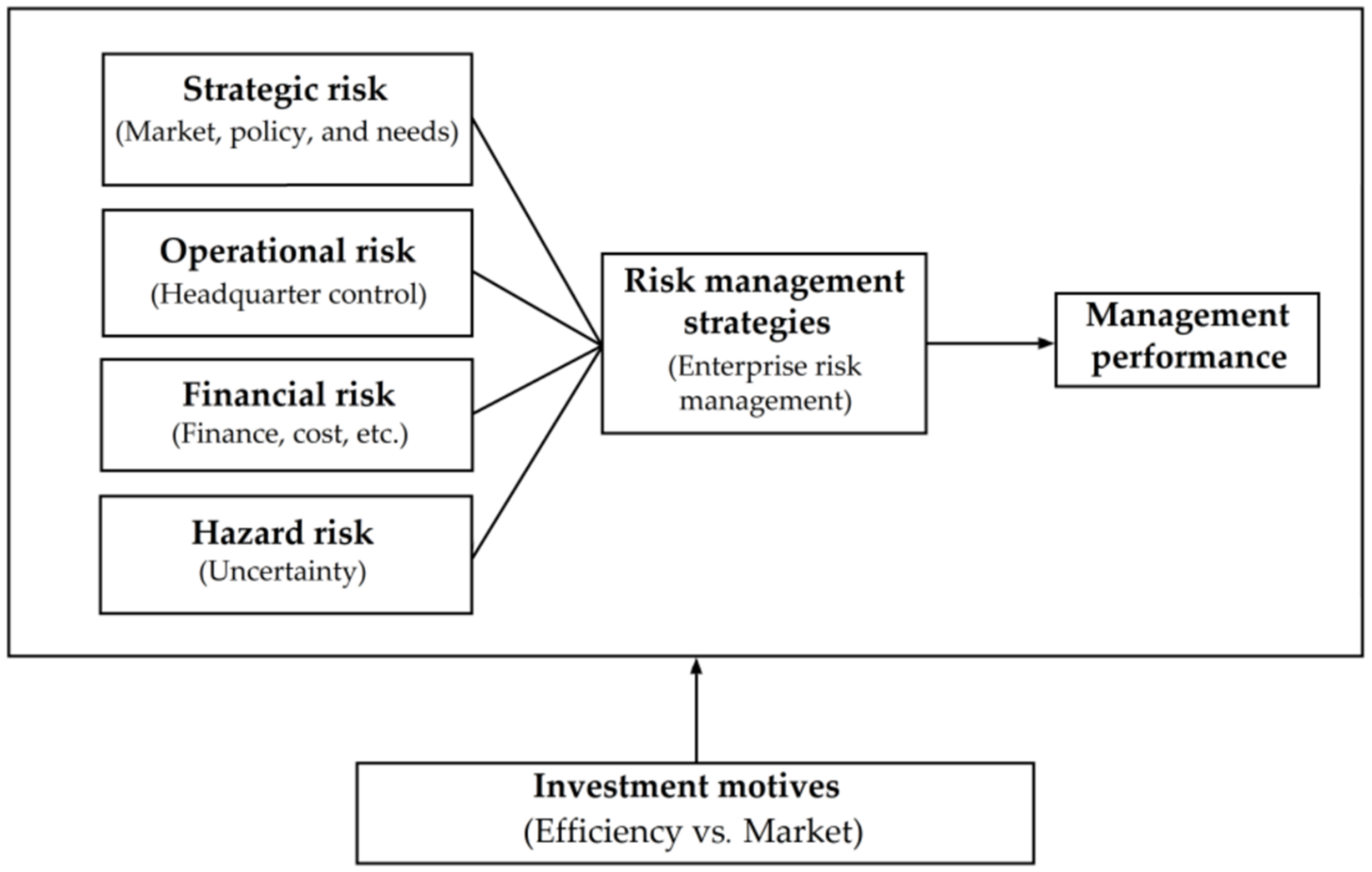

Based on the risk mapping and management framework proposed by Agarwal [

13], this study divides risks into four types: strategic risk, financial risk, operational risk, and accident risk by integrating and combining the existing research on transnational enterprise investment risk [

7,

10,

22,

26]. This will ensure the risk management research framework is more in line with the realities faced by multinational enterprises investing in China. It is worth mentioning that prior to this study, we conducted an informal pilot study involving experts working with SMEs. Later, we planned the study and began the literature review. Data was collected through face-to-face interviews, emails, and telephone calls. It is necessary to mention that the interviews were aimed at gathering information to support this quantitative study. We tried to get as much information as possible and discussed the sample size with statisticians. We also confirmed the sample size by reviewing the online scholarly literature. For this study, we used the established scale described by Kline [

75]. Based on the risk factors of foreign enterprises investing in China, this study divided them into financial, strategic, and HRs. In addition, performance was incorporated as a dependent variable and RM was included as a parameter. As part of the RM process, empirically verified risks from the earlier studies were used as measures, which are now being implemented by businesses in their daily operations. This study examines how RM affects an enterprise’s efficiency-seeking type and market-seeking type, as well as a comparison of the mediating effect according to investment motives. To examine the impact of parameters on independent and dependent variables, research factors were designed, as presented in

Figure 1.

The main focus of this study was to examine manufacturers of foreign enterprises with subsidiaries in China (mostly smaller and medium-sized). The company’s foreign-based headquarters and Chinese branches were surveyed between February and July 2022, and questionnaires were given to executives and managers. In order to perform statistical analysis, both the local visit and e-mail survey methods were simultaneously used, resulting in the collection of a total of 498 copies of the questionnaires.

In our study, we measured the following variables: industry competition, reduction of tax rebates, brand and quality risk, technology gap with local firms, tech leakage, and regulatory reinforcement. As an indicator of FR, we looked at the capital ratio as well as the company’s credit rating, capital support, financing problems, and FRs of affiliates. We also examined the rise in labour, raw materials, rental costs, and maintenance expenses. There are many challenges associated with risk estimations, including difficulty in forecasting future and potential damage, contract changes, consequential losses, and uncertainty regarding investment laws and regulations. The performance measure includes adapting to Chinese markets and policies, increasing profitability and growth in subsidiaries, achieving investment goals, and satisfying management.

This study used statistical routines, viz., Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 18.0 and Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) 18.0 for the verification of developed hypotheses. The SPSS 18.0 program was used for frequency analysis of general characteristics and exploration of factor analysis. AMOS 18.0 was used to perform a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and develop a structural equation model. CFA is used to confirm whether data is suitable to fit the model or not. In order to perform this analysis, we develop a hypothesis based on theoretical research. In this study, depending upon risk type, we have proposed a corresponding hypothesis as aforementioned. The structure equation model used in this study can be represented by the following three matrix equations:

The above equation represents the first matrix equation and is a representation of a structural model. In this equation, η and ξ represent endogenous and exogenous variables, respectively. B and Γ stand for coefficients, and ς represents the error term. The second and third matrix equations are as follows:

The above equations denote measurement models. Here, Y represents variables which can be measured for endogenous variables. Λy is the coefficient of correlation between measurable variables and their corresponding endogenous variables. X and Λx indicate variables which can be measured for exogenous variables and the coefficient of correlation between measurable variables and their corresponding exogenous variables, in that order. Moreover, ε and δ denote errors that occur during the estimation process.

The purpose of this was to verify the suitability of the structural model, hypotheses, and their mediating effects.

Figure 2 illustrates the detailed process of AMOS, outlining the relationship between risk factors, RM, and performance.

5. Discussion

This section presents a comprehensive discussion of market-seeking and efficiency-seeking models. Limitations of this study are also given at the end. It is also very important to mention that all the literature cited in this section confirms our findings. Details are presented along with each type of risk.

5.1. Efficiency-Seeking

When a multinational corporation encounters financial and HRs in its operations in China, it usually does not respond to risks, such as improving the financial structure, increasing financing, or purchasing insurance [

52]. Although the enterprise will actively respond to strategic and ORs, due to the increase in labour costs, the small size of the enterprise and other reasons, even through RM, the enterprise performance improvement is not obvious [

39]. At this time, production efficiency-oriented companies will gradually move to other countries or regions with lower labour costs. Risk response and performance were negatively affected by higher SR, but RM did not mediate this impact. The lack of business competitiveness, a lack of market knowledge, a lack of technology, a lack of foreign networks resulted in “Cost Leadership” for foreign-owned small manufacturing firms. They are unable to present an appropriate RM strategy responding to changes in government policy and tax benefits [

68,

76].

An operations’ RM is observed to have a negative effect on RM, no notable mediating effect on performance, and no meaningful DE on performance. Consequently, if OR increases, RM cannot be conducted efficiently, and the mediating effect is not significant. Production efficiency-oriented companies that export products manufactured by subsidiaries in China to their home countries or third-country markets are said to be more important than securing local market knowledge in the case of coordinating and integrating decision-making between parent companies and subsidiaries. As a result, it implies the need for high levels of management and control at the headquarters of production efficiency-oriented companies. To increase organizational commitment of Chinese employees, contrary to this theoretical correlation, it is necessary to give them responsibilities that will enable them to have clear and well-planned goals, along with more authority.

Because foreign companies entering China have high levels of head office management and control, they are incapable of motivating and assigning responsibilities to local employees, resulting in a decline in the efficiency of local production. Furthermore, since the head office is primarily responsible for research and development and raw material procurement, it cannot present an appropriate operational RM plan that would reflect changes in local consumer behavior. Risk response, RM, and performance were not significantly affected by FR in financial RM. As a result of factors such as rapid increases in labor costs and land prices, if the domestic market is unable to secure competitiveness, efficiency-seeking manufacturing businesses may have difficulty surviving. It is, therefore, more likely that Chinese subsidiaries will withdraw from the market or factories will move to neighboring Southeast Asian countries [

8,

58,

73].

Risk response, RM, and performance were not significantly affected by HRs in hazard RM. As Dudas and Rajnoha [

73] found, the possibility of withdrawal has a positive impact on rather than the management of risk, as indicated by this study. The market condition in the host country disappears if tax laws and regulations frequently change, subsidiaries have an advantage in local management, and the environment degrades [

7,

74]. It is proven that RM directly impacts performance by a statistically significant positive level; however, because of “high administration costs”, all efficiency-seeking models do not have a positive mediating effect, and RM has no meaning [

61].

5.2. Market-Seeking

When an enterprise encounters FRs, the risk response performance is negative. At this time, the enterprise will choose transformation or divestment, or joint venture strategy with other enterprises [

75,

76]. However, when an enterprise encounters strategic, operational, and hazardous risks, it will actively respond and reduce the simple risks in business operation by means of strategic market transformation, digital transformation, human resources re-integration, promoting digital systems, and purchasing various insurances [

77]. High SR significantly affects risk response as well as RM’s ability to enhance performance. By developing localization processes and localized brands, expanding regional R&D, and forming collaborations and partnerships locally, foreign companies in China can enhance their efficiency. They can also innovate processes, improve productivity, and enhance productivity [

7,

42,

54,

60,

78,

79].

In operational RM, it was found that the higher OR, the greater the positive effect on RM and the greater the positive impact on performance through RM, which had a mediating effect and a negative impact on performance. Therefore, when OR increases, RM is actively implemented, and performance can be improved by using it as a medium. In addition, failure to manage OR factors directly reduces performance. This is consistent with adopting a strategy to secure the decision-making authority of subsidiaries and have a positive effect on performance. A higher FR impacted risk response more negatively and mediated performance through RM more negatively. A rising liability ratio results in a falling credit rating, a lower capital adequacy ratio, and subsidiaries’ local financing in China becomes impossible, resulting in an FR. Accordingly, when the financial situation of the head office declines, the subsidiaries’ financial RM cannot be effectively carried out [

64,

80]. It is more likely that subsidiaries will develop products with high value-added industries if they experience an increase in overall costs of corporate management, including materials, rentals, and operating income [

73].

Higher HR had an effect (positive) on risk response, and it also had a mediating effect on performance. By examining local regulations and legal content thoroughly, protecting property rights, and enhancing employee skills and motivation, foreign companies can increase performance. Expatriate executives can live with local subsidiary employees and receive insurance coverage before advancement [

15,

61,

70]. There has been some evidence that foreign-owned subsidiaries seeking the market in China might be able to bolster their performance by strengthening strategies, sales abilities, research and development capabilities, technology innovation capacity, manufacturing flexibility, and workforce development [

39,

52,

75,

81].

5.3. General Discussion

Recently, the development of the digital economy has created many new business forms and new business models, providing new opportunities for multinational enterprises to develop in China. Currently, China has formed the biggest and most active digital service market, and the global proportion of e-commerce sales increased from 8% in 2012 to 57% in 2021 [

82]. For multinationals in China, in the wave of digitalization, they should combine their global advantages with the characteristics of the Chinese market to speed up their digital transformation so as to better cope with external uncertainties. During the epidemic, transnational enterprises with a higher degree of digitalization are less affected by COVID-19 [

83]. Digital transformation emphasizes value more than cost, which belongs to strategic thinking. However, it is difficult for enterprise leaders to change from operational thinking when they need to defend against losses and increase profits in the short term. This is a major challenge for executives who are committed to reforming the organization from within.

Increasing foreign investment has played a crucial role in China’s economic growth as it promotes dual circulation models to deal with complex internal and external challenges [

76]. Since FDI is expanding rapidly in the Yangtze River Delta economic belt, it is crucial in this development strategy [

2]. This research focuses on the RM performance of FDIs in the Yangtze River Delta economic belt. There is both market-seeking FDIs and efficiency-seeking FDIs in this area. According to the statistical results of this empirical research, appropriate corresponding measures could not eliminate all risks associated with efficiency-seeking enterprises. As a consequence, they cannot implement a cost leadership strategy in China due to factors such as increasing management expenses, lessening support for tax, and strengthening regulations. In the absence of RM (ex., Assembly of a mechanical part and exporting it to a third country, etc.), they choose conversion to a large company’s contractors or withdrawal (U-turn back to Foreign or relocation to a third country).

Strategic and HRs of domestic market-seeking enterprises can be mitigated through appropriate corresponding measures as they improve. However, FRs cannot be controlled by appropriate measures if the head office’s financial state deteriorates and total management costs increase. Companies that are more domestically oriented tend to offer their employees better education and training, provide more diverse welfare benefits, and have higher wages, performance-based compensation, fair personnel evaluation, and career development systems that encourage long-term service compared to competitors. Increasing competitive advantage through the implementation of a human resources system will have a positive effect on performance. Globally, market-seeking type companies adapt to policy change (reduce pollution, etc.) through joint ventures with local companies (ex, Eland and Parkson, Hyundai, Beijing automobile, etc.), establishing subsidiaries in smaller cities following brand recognition as well as reliability (ex, electronics industry, fashion, etc.), developing diverse financial and business models through diversification (ex, invest in real estate, a fusion of manufacturing and finance, the launch of local brands, etc.), and employing local human resource and organization management. The headquarters of a company that seeks efficiency can easily control its corporate strategy and withdrawal possibilities, whereas a company seeking market share needs to implement localizing strategies and structures that manage risks intensively.

5.4. Limitations

Similar to most research, our study is subject to potential limitations. As we only focus on foreign–Chinese joint ventures as a sample for empirical analysis and do not measure and compare the results of enterprises from other countries, the generalizability of the study results is limited. Due to limited data, empirical results may lack credibility. Therefore, upcoming studies should pay more attention to data collection and enrich research results through accurate comparative analysis. Future research also needs to examine the ways in which firms or industries measure levels of risk. In addition, future research should also examine how to monitor the effect of the COSO process on RM. Additionally, it is vital to analyze the RM impact of foreign industries entering the service sector, including financial institutions and subsidiaries, to satisfy local consumer preferences. It will be important to understand the risks of foreign–Chinese joint ventures and develop appropriate RM strategies.

6. Conclusions

The Chinese government has proposed a dual circulation economic development strategy to deal with the complexity of global issues under the influence of COVID-19. As a result, China is increasingly dependent on FDI. It is, therefore, crucial to managing the risks associated with FDI. In spite of the diversity of corporate risks, there is a growing consensus that risks can be classified into four quadrants: FR, SR, HR, and OR. Due to risk management failures or unexpected risks, strategic management has attributed withdrawal to production costs or marketing, but risk management has never addressed it. Moreover, SMEs are more vulnerable to risks than large ones. Currently, the published literature fails to explain how SMEs can manage FDI effectively by taking risks into consideration. This study fills this gap for the first time by combining Dunning’s investment motives theory with COSO risk management process theory to examine SMEs’ risk perception in China. The study also tests four hypotheses related to FDI characteristics, performance, and risk management based on the relevant literature. The data for the statistical analysis came from a questionnaire survey of 498 FDIs.

SPSS 18.0 program was used for frequency analysis of general characteristics and exploration of factor analysis, whereas AMOS 18.0 was used to perform a confirmatory factor analysis and develop a structural equation model. The findings indicate that for efficiency-seeking SMEs, strategic risk and operational risk have a significant impact on risk management, whereas, for market-seeking SMEs, all risks, i.e., strategic risk, operational risk, financial risk, and hazard risk, have a significant impact on risk management. On the other hand, for efficiency-seeking SMEs, strategic risk has a significant impact on performance, whereas for market-seeking SMEs, operational risk has a significant impact on risk performance. Moreover, efficiency-oriented enterprises can modify their strategies by implementing digital transformation and localization strategies, whereas production efficiency-oriented enterprises will divest because of risks without finding a better strategy. Thus, this study contributes to understanding the risks associated with FDI and can serve to develop management strategies.

The results of this study have some implications for the investment risk management of foreign SMEs in China. First, according to the investment motivation of the enterprise, SMEs need to select the location for investment. For example, enterprises that need high-quality talents, advanced equipment, and technology can choose to invest in coastal provinces in eastern China (such as Zhejiang Province, where the digital economy is most popular), and those that need low land rents and labour can choose to invest in cities in central and western China. In addition, China is currently at the forefront of the digital revolution. In order to meet the needs of local market competition, foreign SMEs should speed up digital transformation. They must change the traditional business model, weaken the boundaries of enterprises, and make consumer demand more consistent with commodity supply. Furthermore, due to cash flow risks and reduced revenue, large companies did not withdraw their investment during COVID-19 but rather made digital transformations or were kept waiting. Despite this, when SMEs in many countries faced COVID-19 risks in China, divestment was conducted, so this study can accurately reflect ongoing FDI conditions. Therefore, this study can help FDIs to develop reliable risk-management strategies.