Workplace Favoritism and Workforce Sustainability: An Analysis of Employees’ Well-Being

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement/Research Question

- Do practicing managers favor selected individuals because of their vested interest or is there any positivity in such practices?

- To what degree does the damaging impact of favoritism affect employees’ well-being and the sustainability of the workforce?

1.2. Research Background

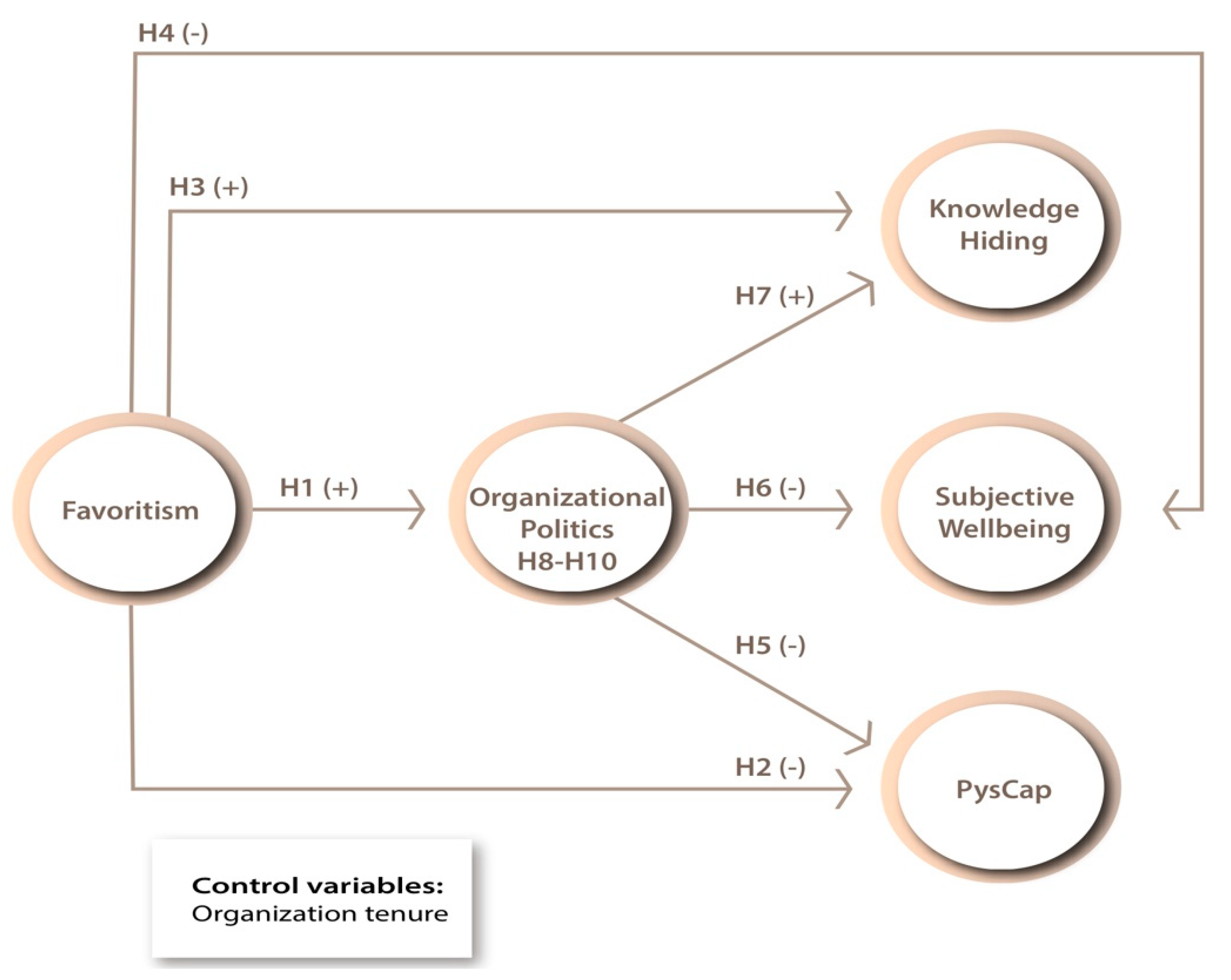

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Instrumentation

3.3. Analysis Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Testing

4.2. Result of Hypothesized Linkages

5. Discussion

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Future Recommendation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boxall, P.; Purcell, J.; Wright, P.M. Human Resource Management. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Resource Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lasisi, T.T.; Eluwole, K.K.; Ozturen, A.; Avci, T. Explanatory investigation of the moderating role of employee proactivity on the causal relationship between innovation-based human resource management and employee satisfaction. J. Public Aff. 2020, 20, e2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, H.F.; Maghrabi, A.S.; Raggad, B.G. Assessing the perceptions of human resource managers toward nepotism. Int. J. Manpow. 1998, 19, 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H. Workplace spirituality and nepotism-favouritism in selected ASEAN countries: The role of gender as moderator. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2020, 14, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Namin, B.H.; Harazneh, I.; Arasli, H.; Tunç, T. Does gender moderates the relationship between favoritism/nepotism, supervisor incivility, cynicism and workplace withdrawal: A neural network and SEM approach. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, H.E.; Arasli, H.; Arici, N.C. The effect of nepotism on tolerance to workplace incivility: Mediating role of psychological contract violation and moderating role of authentic leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, H.E.; Arasli, H.; Çobanoğlu, C.; Namin, B.H. The Effect Of Favoritism On Job Embeddedness In The Hospitality Industry: A Mediation Study Of Organizational Justice. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2019, 22, 383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Anasori, E.; Lasisi, T.T. Physical attractiveness and managerial favoritism in the hotel industry: The light and dark side of erotic capital. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.L.; Cheng, C.F. A Mediation Model of Leaders’ Favoritism. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 1330–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H.; Arici, H.E.; Çakmakoğlu Arici, N. Workplace favoritism, psychological contract violation and turnover intention: Moderating roles of authentic leadership and job insecurity climate. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 33, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.A. A Formal Interpretation of the Theory of Relative Deprivation. Sociometry 1959, 22, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Sparrowe, R.T.; Wayne, S.J. Leader-Member Exchange Theory: The Past and Potential for the Future. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1997, 15, 47–120. [Google Scholar]

- Nawal, A.; Awang, Z.; Rehman, A.U.; Mehmood, H. Nexus among Perceived Organizational Politics and Organizational Citizenship Behavior Under the lenses of Social Exchange Perceptions. J. Manag. Theory Pr. 2020, 1, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, Y.M.; Zaman, H.M.; Hashmi, Z.I.; Marri, M.Y.K.; Khan, A.R. Impact of Favoritism, Nepotism and Cronyism on Job Satisfaction a Study from Public Sector of Pakistan Waste Management View Project Project Performance View Project. Manag. Arts 2013, 64, 19328–19332. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity in Social Exchange. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 2, 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Daskin, M.; Tezer, M. Organizational Politics and Turnover: An Empirical Research from Hospitality Industry. Tourism 2012, 60, 273–291. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, J.-O.; Kim, T. Testing the Relationship Between Perceived Organizational Politics and Organizational Performance: Task and Relationship Conflict as Mediators. Public Organ. Rev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaed, L.M. The Effect of Nepotism/Favoritism on Flight Attendant’s Emotional Exhaustion and Job Performance: The Moderating Role of Psychological Capital. Master’s Thesis, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, Cyprus, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: From the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2716–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, J.R.C.; Näswall, K.; Malinen, S. Resilient Employees in Resilient Organizations: Flourishing Beyond Adversity. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 9, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strik, N.P.; Hamstra, M.R.W.; Segers, M.S.R. Antecedents of Knowledge Withholding: A Systematic Review & Integrative Framework. Group Organ. Manag. 2021, 46, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrough, A.R.; Froehlich, L.; Eriksson, K. Cooperation in the cross-national context. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.L.; Collette, T. Culture and Social Behavior. In Culture across the Curriculum; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Zhang, X.; Ng, B.C.S.; Zhong, L. To Empower or Not to Empower? Multilevel Effects of Empowering Leadership on Knowledge Hiding. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miminoshvili, M.; Černe, M. Workplace inclusion–exclusion and knowledge-hiding behaviour of minority members. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pr. 2022, 20, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, D.; Seth, M. Can Organizational Grapevine Be Beneficial? An Exploratory Study in Indian Context; Indian Institute of Management Kozhikode: Kerala, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, M.; Krasko, J.; Terwiel, S. Subjective well-being as a dynamic construct. In The Handbook of Personality Dynamics and Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 1231–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, M.; Hawkley, L.C.; Eid, M.; Cacioppo, J.T. Time frames and the distinction between affective and cognitive well-being. J. Res. Pers. 2012, 46, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Das, K.V.; Jones-Harrell, C.; Fan, Y.; Ramaswami, A.; Orlove, B.; Botchwey, N. Understanding subjective well-being: Perspectives from psychology and public health. Public Health Rev. 2020, 41, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, V.; Phung, S.P. Economic Dimensions of Blockchain Technology: In the Context of Extention of Cryptocurrencies. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabilitation 2020, 24, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, M.; Polas, H.; Raju, V.; Muhibbullah; Tabash, M.I. Rural women characteristics and sustainable entrepreneurial intention: A road to economic growth in Bangladesh. J. Enterprising Communities: People Places Glob. Econ. 2021, 16, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, S.; Almadani, A.; Al Tuwariqi, M.; Alzahrani, F.; Alshabri, M.; Khoja, M.; Al Dakheel, K.; Alghalayini, K.; Alkadi, N.; Aljebreen, S.; et al. Burnout, Depression, and Anxiety Levels among Healthcare Workers Serving Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.C.; Ferris, D.L.; Brown, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Yan, M. Perceptions of Organizational Politics: A Need Satisfaction Paradigm. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 1026–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, M.; Kacmar, K.M.; Zivnuska, S. Understanding the Effects of Political Environments on Unethical Behavior in Organizations. J. Bus. Ethic- 2019, 156, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Kong, Y.; Niu, J.; Gao, W.; Li, J.; Li, M. How Leaders’ Psychological Capital Influence Their Followers’ Psychological Capital: Social Exchange or Emotional Contagion. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seo, D.-T. The Impact of Employee’s Perceptions of Organizational Politics and Burnout: Role of Psychological Need Satisfaction and Psychological Capital. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2016, 16, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thiel, C.E.; Hill, J.; Griffith, J.; Connelly, S. Political tactics as affective events: Implications for individual perception and attitude. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2012, 23, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G.R.; Ellen, B.P.; McAllister, C.P.; Maher, L.P. Reorganizing Organizational Politics Research: A Review of the Literature and Identification of Future Research Directions. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2019, 6, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C. Employee well-being in organizations: Theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochwarter, W.A.; Rosen, C.C.; Jordan, S.L.; Ferris, G.R.; Ejaz, A.; Maher, L.P. Perceptions of Organizational Politics Research: Past, Present, and Future. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 879–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenko, A.; Bontis, N. Understanding Counterproductive Knowledge Behavior: Antecedents and Conseque Knowledge Hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 1199–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modem, R.; Lakshminarayanan, S.; Pattusamy, M.; Rajasekharan, P.K.; Prabhu, N. Is Knowledge Hiding in Higher Education a Political Phenomenon? An Explanatory Sequential Approach to Explore Non-Linear and Three-Way Interaction Effects. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparel, N.; Choubisa, R. Knowledge Hiding in Organizations: A Retrospective Narrative Review and the Way Forward. Dyn. Relatsh. Manag. J. 2020, 9, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, O.F.; Shahzad, A.; Raziq, M.M.; Khan, M.M.; Yusaf, S.; Khan, A. Perceptions of organizational politics, knowledge hiding, and employee creativity: The moderating role of professional commitment. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 142, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.N.; Lam, L.W. Obligations and feeling envied: A study of workplace status and knowledge hiding. J. Manag. Psychol. 2020, 35, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukeje, U.E.; Lasisi, T.T.; Eluwole, K.K.; Titov, E.; Ozturen, A. Organizational level antecedents of value co-destruction in hospitality industry: An investigation of the moderating role of employee attribution. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunmokun, O.A.; Eluwole, K.K.; Avci, T.; Lasisi, T.T.; Ikhide, J.E. Propensity to trust and knowledge sharing behavior: An evaluation of importance-performance analysis among Nigerian restaurant employees. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwol, V.S.; Avci, T.; Eluwole, K.K.; Dalhatu, A. Food safety knowledge and hygienic-sanitary control: A needed company for public well-being. J. Public Aff. 2019, 20, e2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M.O.; Öztüren, A.; Cobanoglu, C.; Arasli, H.; Eluwole, K.K. Employees’ perception of robots and robot-induced unemployment in hospitality industry under COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatepe, T.; Ozturen, A.; Karatepe, O.M.; Uner, M.M.; Kim, T.T. Management commitment to the ecological environment, green work engagement and their effects on hotel employees’ green work outcomes. Int. J. Cont. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 3084–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eluwole, K.K.; Ukeje, U.E.; Saydam, M.B.; Ozturen, A.; Lasisi, T.T. Behavioural response to abusive supervision among hotel employees: The intervening roles of forgiveness climate and helping behaviour. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2022, 72, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.G.; Lin, Z.; Wong, I.A.; Chen, Y.; So, A.C.Y. When employees fight back: Investigating how customer incivility and procedural injustice can impel employee retaliation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacmar, K.M.; Ferris, G.R. Perceptions of Organizational Politics Scale (POPS): Development and Construct Validation. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1991, 51, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Norman, S.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B. The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate—Employee performance relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 29, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Ali, F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Convergence of Structural Equation Modeling and Multilevel Modeling. In The SAGE Handbook of Innovation in Social Research Methods; Williams, M., Paul, V.W., Eds.; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eluwole, K.K.; Karatepe, O.M.; Avci, T. Ethical leadership, trust in organization and their impacts on critical hotel employee outcomes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plan. Int. J. Strateg. Manag. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, J.; Lim, J. Model Fit Measures. Google Scholar. 2016. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Gaskin%2C+J.+%26+Lim%2C+J.+%282016%29%2C+%22Model+Fit+Measures&btnG= (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2000, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Sofyan, Y.; Shang, Y.; Romani, L.E. Perceived organizational politics, knowledge hiding and diminished promotability: How do harmony motives matter? J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 1826–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H.; Tümer, M. Nepotism, Favoritism and Cronyism: A Study of Their Effects on Job Stress and Job Satisfaction in the Banking Industry of North Cyprus. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2008, 36, 1237–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 268 | 51.7 |

| Female | 250 | 48.3 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–27 | 149 | 28.8 |

| 28–37 | 209 | 40.3 |

| 38–47 | 85 | 16.4 |

| 48–57 | 51 | 9.8 |

| 58 or above | 24 | 4.6 |

| Education level | ||

| Primary | 60 | 11.6 |

| Secondary | 77 | 14.9 |

| Vocational | 114 | 22.0 |

| Bachelors | 233 | 45.0 |

| Masters/PhD | 34 | 6.6 |

| Organizational tenure (years) | ||

| Under 1 | 135 | 26.1 |

| 1–5 | 176 | 34.0 |

| 6–10 | 111 | 21.4 |

| 11–15 | 53 | 10.2 |

| 16–20 | 27 | 5.2 |

| 20 or more | 16 | 3.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single/divorced | 231 | 44.6 |

| Married | 287 | 55.4 |

| Income (NGN) | ||

| Under 50,000 | 139 | 26.8 |

| 50,001–100,000 | 156 | 30.1 |

| 100,001–150,000 | 128 | 24.7 |

| 150,001 or more | 95 | 18.3 |

| Income is measured in Naira. | ||

| Variables | Standardized Loadings | t-Values | AVE | Lower 95% AVE | Upper 95% AVE | CR | Lower 95% CR | Upper 95% CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favoritism | 0.862 | 0.804 | 0.912 | 0.989 | 0.983 | 0.993 | ||

| FAV1 | 0.994 *** | 185.31 | ||||||

| FAV2 | 0.946 *** | 65.65 | ||||||

| FAV3 | 0.998 | Constrained | ||||||

| FAV4 | 0.976 *** | 98.82 | ||||||

| FAV5 | 0.983 *** | 115.81 | ||||||

| FAV6 | 0.972 *** | 92.05 | ||||||

| FAV7 | 0.991 *** | 154.19 | ||||||

| FAV8 | 0.887 *** | 43.44 | ||||||

| FAV9 | 0.778 *** | 28.06 | ||||||

| FAV10 | 0.765 *** | 26.93 | ||||||

| FAV11 | 0.940 *** | 61.54 | ||||||

| FAV12 | 0.914 *** | 50.72 | ||||||

| FAV13 | 0.973 *** | 93.32 | ||||||

| FAV14 | 0.838 *** | 34.77 | ||||||

| Organizational Politics | 0.691 | 0.629 | 0.745 | 0.964 | 0.953 | 0.972 | ||

| OrgP1 | 0.837 *** | 26.94 | ||||||

| OrgP2 | 0.738 *** | 21.36 | ||||||

| OrgP3 | 0.849 *** | 27.77 | ||||||

| OrgP4 | 0.847 *** | 27.65 | ||||||

| OrgP5 | 0.852 *** | 27.97 | ||||||

| OrgP6 | 0.884 *** | 30.40 | ||||||

| OrgP7 | 0.873 *** | 29.58 | ||||||

| OrgP8 | 0.894 *** | 31.22 | ||||||

| OrgP9 | 0.891 *** | 30.98 | ||||||

| OrgP10 | 0.892 | Constrained | ||||||

| OrgP11 | 0.711 *** | 20.09 | ||||||

| OrgP12 | 0.665 *** | 18.14 | ||||||

| Reciprocal Knowledge Hiding | 0.909 | 0.871 | 0.942 | 0.968 | 0.953 | 0.980 | ||

| RKH1 | 0.982 | Constrained | ||||||

| RKH2 | 0.950 *** | 55.49 | ||||||

| RKH3 | 0.927 *** | 48.23 | ||||||

| Employee’s subjective well-being | 0.480 | 0.336 | 0.764 | 0.821 | 0.714 | 0.908 | ||

| SWB1 | 0.604 *** | 12.37 | ||||||

| SWB2 | 0.739 | Constrained | ||||||

| SWB3 | 0.732 *** | 14.75 | ||||||

| SWB4 | 0.638 *** | 13.04 | ||||||

| SWB5 | 0.740 *** | 14.87 | ||||||

| Employee’s Psychological capital | 0.749 | 0.960 | ||||||

| PysCap1 | 0.896 *** | 32.62 | ||||||

| PysCap2 | 0.908 | Constrained | ||||||

| PysCap3 | 0.881 *** | 31.24 | ||||||

| PysCap4 | 0.855 *** | 29.08 | ||||||

| PysCap5 | 0.815 *** | 26.19 | ||||||

| PysCap6 | 0.883 *** | 31.42 | ||||||

| PysCap7 | 0.884 *** | 31.56 | ||||||

| PysCap8 | 0.796 *** | 24.98 | ||||||

| Mean | SD | FAV | OrgP | PysCap | SWB | RKH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAV | 3.25 | 1.19 | 0.929 | (0.101) | (0.111) | (0.011) | (0.155) |

| OrgP | 3.91 | 1.48 | 0.140 ** | 0.831 | (0.201) | (0.100) | (0.031) |

| PysCap | 3.68 | 1.34 | −0.141 ** | −0.153 *** | 0.865 | (0.093) | (0.446) |

| SWB | 1.49 | 0.47 | −0.012 | −0.090 † | 0.095 † | 0.693 | (0.089) |

| RKH | 2.87 | 1.36 | 0.186 *** | 0.041 | 0.442 *** | −0.019 | 0.953 |

| Measurement Model | Thresholds | Interpretation | Constrained Single-Factor Model | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 = 2413.51, df = 807 | χ2 = 14,929.66, df = 817 | |||

| χ2/df = 2.99 | Between 1 and 3 [1] | Excellent | χ2/df = 18.27 | Terrible |

| CFI = 0.948 | <0.95 ([60]) | Acceptable | CFI = 0.545 | Terrible |

| TLI = 0.945 | 1 = maximum fit [3] | Acceptable | TLI = 0.520 | Terrible |

| NFI = 0.924 | 1 = maximum fit [3] | Acceptable | NFI = 0.531 | Terrible |

| IFI = 0.948 | 1 = maximum fit [3] | Acceptable | IFI = 0.545 | Terrible |

| RMSEA = 0.062 | >0.06 <0.08 ([61]) | Acceptable | RMSEA = 0.183 | Terrible |

| SRMR = 0.032 | <0.08 ([62]) | Excellent | SRMR = 0.253 | Terrible |

| Hypothesis | Path | Estimate | Lower BaCI | Upper BaCI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Favoritism → Organizational politics | 0.168 | 0.085 | 0.254 | Supported |

| 2 | Favoritism → Psychological capital | −0.136 | −0.225 | −0.033 | Supported |

| 3 | Favoritism → Reciprocal knowledge hiding | 0.214 | 0.136 | 0.301 | Supported |

| 4 | Favoritism → Employee’s subjective well-being | −0.043 | −0.031 | 0.024 | Unsupported |

| 5 | Organizational politics → Knowledge hiding | 0.061 | −0.031 | 0.123 | Unsupported |

| 6 | Organizational politics → Subjective well-being | −0.027 | −0.044 | −0.006 | Supported |

| 7 | Organizational politics → Psychological capital | −0.125 | −0.193 | −0.055 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lasisi, T.T.; Constanţa, E.; Eluwole, K.K. Workplace Favoritism and Workforce Sustainability: An Analysis of Employees’ Well-Being. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14991. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214991

Lasisi TT, Constanţa E, Eluwole KK. Workplace Favoritism and Workforce Sustainability: An Analysis of Employees’ Well-Being. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):14991. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214991

Chicago/Turabian StyleLasisi, Taiwo Temitope, Enea Constanţa, and Kayode Kolawole Eluwole. 2022. "Workplace Favoritism and Workforce Sustainability: An Analysis of Employees’ Well-Being" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 14991. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214991