Learning from Failure: Building Resilience in Small- and Medium-Sized Tourism Enterprises, the Role of Servant Leadership and Transparent Communication

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Basis and Hypothesis

2.1. The DRFH and Social Exchange Theory

2.2. Servant Leadership (a Social Capital)

2.3. Transparent Communication (a Social Capital)

2.4. Resilience of the Employees (a Human Capital)

2.5. Adaptive Performance (an Indicator of Business Resilience)

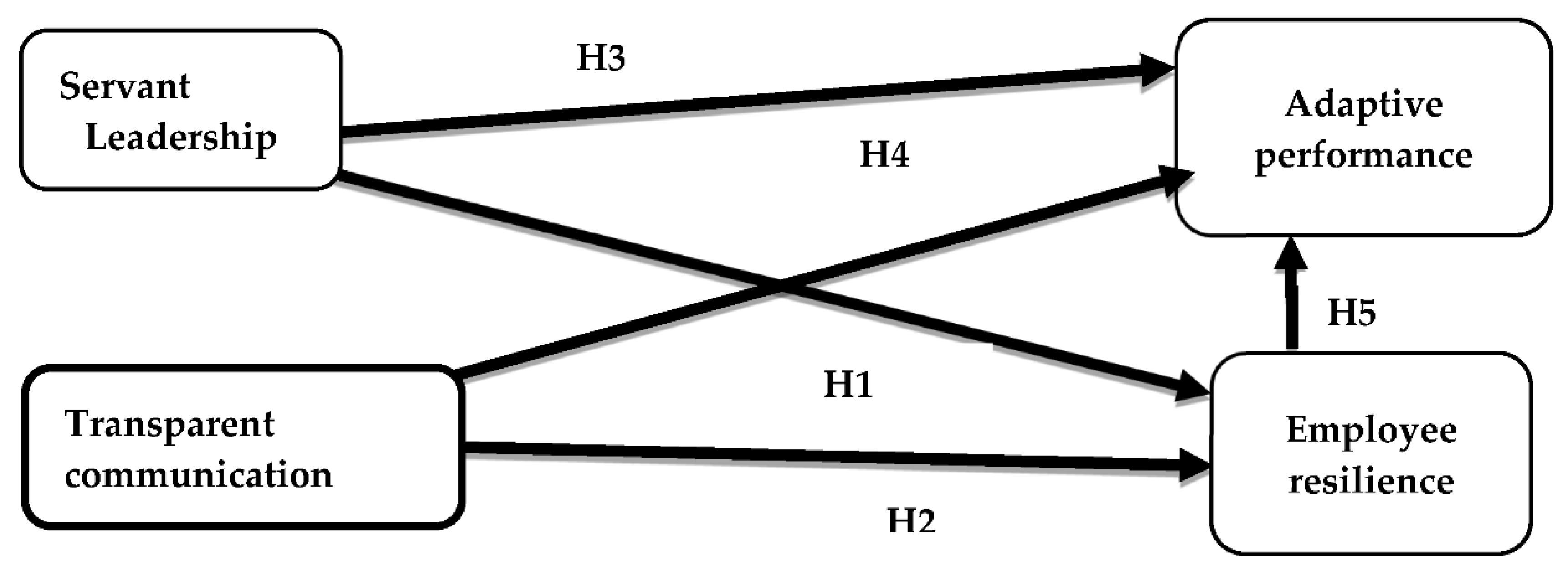

2.6. Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement Development

3.2. Participants and Process of Collecting Data

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Findings from Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model (CFA)

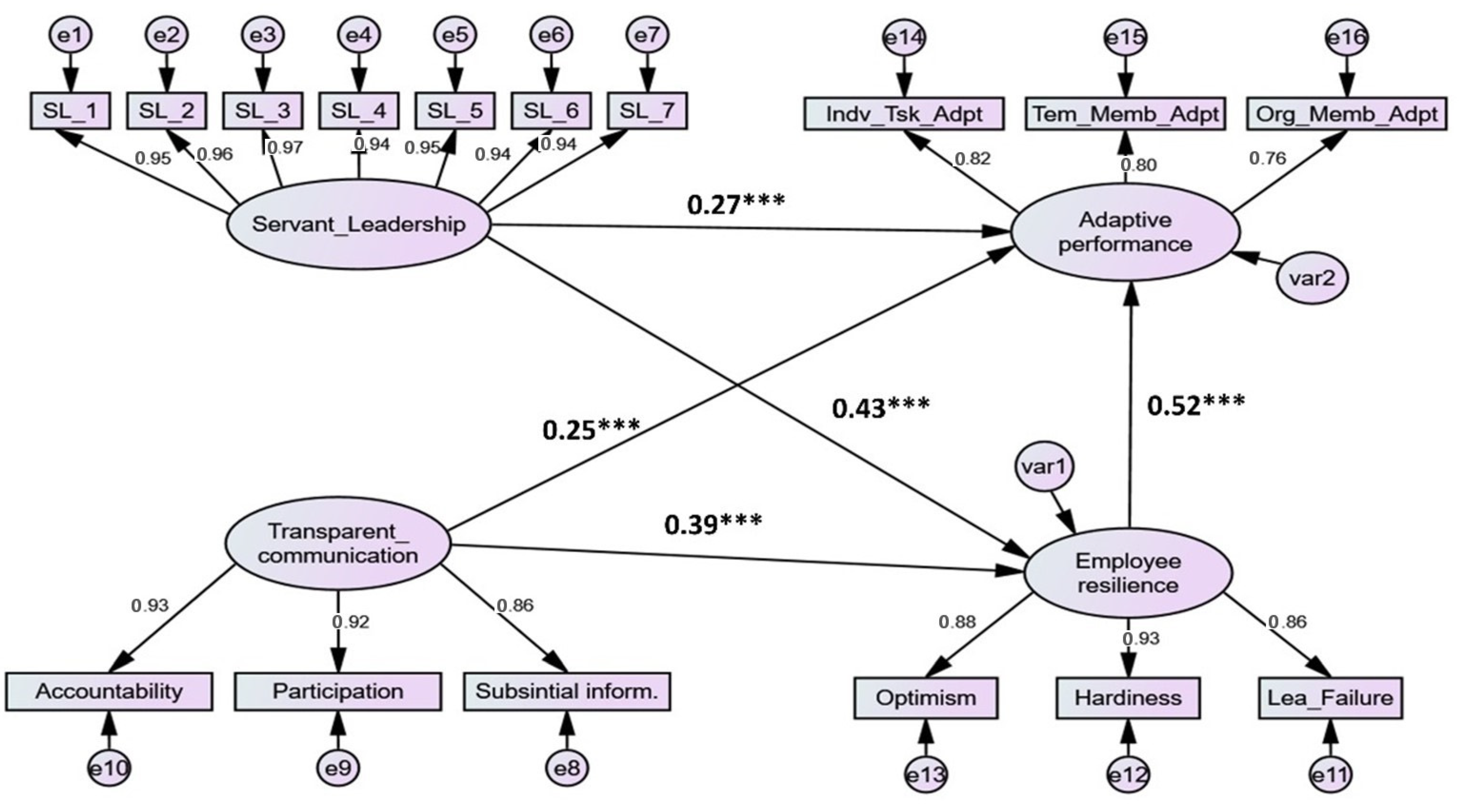

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

5.3. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luthans, F. Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2002, 16, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ozanne, L.; de Vries, H. Psychological capital, coping mechanisms and organizational resilience: Insights from the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake, New Zealand. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100637. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.; Verreynne, M. Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: A dynamic capabilities view. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, S.; McNaughton, R. Resilience and entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 1129–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K.; Vogus, T. Organizing for resilience. In Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Britt, T.; Shen, W.; Sinclair, R.; Grossman, M.; Klieger, D. How much do we really know about employee resilience? Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 9, 378–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Men, R. Creating an engaged workforce: The impact of authentic leadership, transparent organizational communication, and work-life enrichment. Commun. Res. 2017, 44, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, G.; Messeni-Petruzzelli, A.; Del Giudice, M. Searching for resilience: The impact of employee-level and entrepreneur-level resilience on firm performance in small family firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 57, 445–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, R.K. Managing resilience of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) during COVID-19: Analysis of barriers. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhatwani, M.; Mishra, S.K.; Varma, A.; Rai, H. Psychological resilience and business survival chances: A study of small firms in the USA during COVID-19. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Song, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Huang, L.; Chen, X. Shame on You! When and Why Failure-Induced Shame Impedes Employees’ Learning from Failure in the Chinese Context. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 725277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; He, J.; Morrison, A.; Andres Coca-Stefaniak, J. Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: From the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2716–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, J.; Malinen, S.; Näswall, K. Employee resilience: Directions for resilience development. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2017, 69, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, S. Employee adaptive performance and its antecedents: Review and synthesis. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2019, 18, 294–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonnier-Voirin, A.; Roussel, P. Adaptive performance: A new scale to measure individual performance in organizations. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2012, 29, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakos, E.; Arad, S.; Donovan, M.; Plamondon, K. Adaptability in the work place: Development of taxonomy of adaptive performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, K.; Witt, L.; Shoss, M. The interactive effect of leader-member exchange and perceived organizational support on employee adaptive performance. J. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 15, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Wen, J.; Smith, S.M.; Stokes, P. Building-up resilience and being effective leaders in the workplace: A systematic review and synthesis model. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R. Servant Leadership; Paulist Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dierendonck, D. Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1228–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, J.; Bommer, W.; Dulebohn, J.; Wu, D. Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.A. When a servant-leader comes knocking…. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2009, 30, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Canavesi, A.; Minelli, E. Servant leadership: A systematic literature review and network analysis. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2021, 34, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliot, J. Resilient leadership: The impact of a servant leader on the resilience of their followers. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2020, 22, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Orchiston, C.; Rovins, J.; Feldmann-Jensen, S.; Johnston, D. An integrative framework for investigating disaster resilience within the hotel sector. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Rovins, J.; Feldmann-Jensen, S.; Orchiston, C.; Johnston, D. Exploring disaster resilience within the hotel sector: A systematic review of literature. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 22, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivkov, M.; Blešić, I.; Janićević, S.; Kovačić, S.; Miljković, Ð.; Lukić, T.; Sakulski, D. Natural disasters vs hotel industry resilience: An exploratory study among hotel managers from Europe. Open Geosci. 2019, 11, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, R.F.; Wang, X.; Madera, J.M.; Abbott, J. Organizational trust in times of COVID-19: Hospitality employees’ affective responses to managers’ communication. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc Su, D.; Luc Tra, D.; Thi Huynh, H.; Nguyen, H.; O’Mahony, B. Enhancing resilience in the Covid-19 crisis: Lessons from human resource management practices in Vietnam. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3189–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.; Kuntz, J.; Näswall, K.; Malinen, S. Employees’ resilience and leadership styles: The moderating role of proactive personality and optimism. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2016, 45, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, S.; Elshaer, I. Justice and trust’s role in employees’ resilience and business’ continuity: Evidence from Egypt. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, D.; Çubuk, D.; Uslu, T. The effect of organizational support, transformational leadership, personnel empowerment, work engagement, performance and demographical variables on the factors of psychological capital. EMAJ Emerg. Mark. J. 2014, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, A. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.; Panaccio, A.; Meuser, J.; Hu, J.; Wayne, S. Servant Leadership: Antecedents, Processes, and Outcomes. In Oxford Library of Psychology. The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Day, D.V., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 357–379. [Google Scholar]

- Rivkin, W.; Diestel, S.; Schmidt, K. The positive relationship between servant leadership and employees’ psychological health: A multi-method approach. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N.; Robin, M.; Sendjaya, S.; van Dierendonck, D.; Liden, R. Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.; Wayne, S.; Liao, C.; Meuser, J. Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, B. Give the emperor a mirror: Toward developing a stakeholder measurement of organizational transparency. J. Public Relat. Res. 2009, 21, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strathern, M. The tyranny of transparency. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2000, 26, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterrell, R. Transparency, mass media, ideology and community. Cult. Values 2000, 3, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D. Change communication: Using strategic employee communication to facilitate major change. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2002, 7, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, M.; Men, L.; Yue, C. How communication climate and organizational identification impact change. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2019, 25, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapscott, D.; Ticoll, D. The Naked Corporation: How the Age of Transparency will Revolutionize Business; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, J. Entrepreneurial learning from failure: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 604–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, P.D.; Singh, S.; Pavlovich, K. Entrepreneurial resilience and venture failure. Int. Small Bus. J. 2017, 35, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H.; Wolfe, M. Moving forward from project failure: Negative emotions, affective commitment, and learning from the experience. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1229–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G.; Vignoli, M.; Petruzziello, G.; Palareti, L. The Hardier You Are, the Healthier You Become. May Hardiness and Engagement Explain the Relationship Between Leadership and Employees’ Health? Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyaupane, G.; Prayag, G.; Godwyll, J.; White, D. Toward a resilient organization: Analysis of employee skills and organization adaptive traits. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 658–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Spector, S.; Orchiston, C.; Chowdhury, M. Psychological resilience, organizational resilience and life satisfaction in tourism firms: Insights from the Canterbury earthquakes. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1216–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakos, E.; Schmitt, N.; Dorsey, D.; Arad, S.; Berman, W.; Hedge, J. Predicting adaptive performance: Further tests of a model of adaptability. Hum. Perform. 2002, 15, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.; Neal, A.; Parker, S. A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M.; Witt, L.; Vera, D. When does adaptive performance lead to higher task performance? J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 910–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendjaya, S. Personal and Organizational Excellence through Servant Leadership: Learning to Serve, Serving to Lead, Leading to Transform; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koyuncu, M.; Burke, R.J.; Astakhova, M.; Eren, D.; Cetin, H. Servant leadership and perceptions of service quality provided by front-line service workers in hotels in Turkey: Achieving competitive advantage. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 1083–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Dooley, L.; Xie, L. How servant leadership and self-efficacy interact to affect service quality in the hospitality industry: A polynomial regression with response surface analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B.; Karatepe, O. Does servant leadership better explain work engagement, career satisfaction and adaptive performance than authentic leadership? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2075–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartone, P. Leader influences on resilience and adaptability in organizations. In The Routledge International Handbook of Psychosocial Resilience; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 355–368. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, C.; Lee, Y.; Chen, W. The effect of servant leadership on customer value co-creation: A cross-level analysis of key mediating roles. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, E. Crisis communication in public organisations: Dimensions of crisis communication revisited. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2014, 22, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, R.; Tao, W.; Lee, Y. Employee coping with organizational change in the face of a pandemic: The role of transparent internal communication. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranzl, J.; Ruppel, C.; Einwiller, S. Examining the Role of Transparent Organizational Communication for Employees’ Job Engagement and Disengagement during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Austria. J. Int. Crisis Risk Commun. Res. 2021, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruck, K.; Men, L.R. Guest editorial: Internal communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Commun. Manag. 2021, 25, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Men, L.; Ferguson, M. Bridging transformational leadership, transparent communication, and employee openness to change: The mediating role of trust. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 101779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Neesham, C.; Manville, G.; Tse, H. Examining the influence of servant and entrepreneurial leadership on the work outcomes of employees in social enterprises. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2905–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, V.; Dickson, C. Managerial coping strategies during organizational change. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 1993, 30, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Callan, V. The role of social support in coping during the anticipatory stage of organizational change: A test of an integrative model. Br. J. Manag. 2011, 22, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.; Bowen, S. Excellence in Internal Communication Management; Business Expert Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bartone, P.; Kelly, D.; Matthews, M. Psychological hardiness predicts adapt ability in military leaders: A prospective study. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2013, 21, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahaij, R.; Gaillard, A.; van Dam, K. Hardiness and the response to stressful situations: Investigating mediating processes. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pine, J.; Colquitt, J.; Erez, A. Adaptability to changing task contexts: Effects of general cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. Pers. Psychol. 2000, 53, 563–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Zou, S.; Vorhies, D.; Katsikeas, C. Experiential and informational knowledge, architectural marketing capabilities, and the adaptive performance of export ventures: A cross-national study. Decis. Sci. 2003, 34, 287–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nes, L.; Segerstrom, S. Dispositional optimism and coping: A meta-analytic review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.; Davidson, J. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.; Whitney, D. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Moorman, R.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allred, S.; Ross-Davis, A. The drop-off and pick-up method: An approach to reduce nonresponse bias in natural resource surveys. Small-Scale For. 2011, 10, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A.; Cramer, D. Quantitative Data Analysis with IBM SPSS 17, 18 & 19: A Guide for Social Scientists; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.; Heatherton, T. A general approach to representing multifaceted personality constructs: Application to state self-esteem. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1994, 1, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. Structural Equation Modelling: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.; Lomax, R. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch Jr, J.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E. Structural equation modelling in perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownell, J. Leadership in the service of hospitality. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2010, 51, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.; Folke, C. Resilience 2011: Leading transformational change. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Saad, S.K. Entrepreneurial resilience and business continuity in the tourism and hospitality industry: The role of adaptive performance and institutional orientation. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 1365–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Delgado, F.; Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Benlloch-Osuna, M.T.; Heras-Pedrosa, C.D.L.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C. Resilience and anti-stress during COVID-19 isolation in Spain: An analysis through audiovisual spots. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetzer, T.; Hensel, L.; Hermle, J.; Roth, C. Coronavirus perceptions and economic anxiety. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2021, 103, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C.; de Las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Fernandez-Díaz, E. Closer to or further from the new normal? business approach through social media analysis. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, J.; Rahman, M.; Ali, G.G.; Samuel, Y.; Pelaez, A. Feeling like it is time to reopen now? covid-19 new normal scenarios based on reopening sentiment analytics. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.10961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Surprise for science, resilience for ecosystems, and incentives for people. Ecol. Appl. 1996, 6, 733–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N = 880 | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of business | Restaurant employees | 500 | 57% |

| Travel agent employees | 380 | 43% | |

| Gender | Male | 620 | 70% |

| Female | 260 | 30% | |

| Marital status | Married | 619 | 70% |

| Unmarried | 261 | 30% | |

| Age | <30 years | 80 | 10% |

| 30 to 45 years | 500 | 57% | |

| 46 to 60 years | 250 | 28% | |

| More than 60 years | 50 | 5% | |

| Education level | Less than secondary diploma | 150 | 17% |

| Secondary diploma | 320 | 37% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 400 | 46% | |

| Years in operation | Less than 5 years | 317 | 36% |

| 6 to 15 years | 313 | 35% | |

| Over 15 years | 250 | 29% | |

| Abbr. | Items | N | Min. | Max. | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC (Participation); Rawlins [40], Men and Bowen [69]. | ||||||||

| TC_Partc_1 | The firm requests feedback from employees like me on the information quality within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.61 | 0.835 | −0.222 | −0.037 |

| TC_Partc_2 | The firm involves employees like me to help define the information I need within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.58 | 0.811 | −0.244 | 0.092 |

| TC_Partc_3 | The firm gives comprehensive information to employees like me within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.57 | 0.841 | −0.344 | 0.222 |

| TC_Partc_4 | The firm facilitate finding the information employees like me need within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.58 | 0.836 | −0.351 | 0.270 |

| TC_Partc_5 | The firm requests the viewpoints of employees like me before making decisions within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.56 | 0.830 | −0.221 | −0.036 |

| TC_Partc_6 | The firm takes the time with employees like me to understand who we are and what we need within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.57 | 0.849 | −0.350 | 0.224 |

| TC (Substantiality information); Rawlins [40], Men and Bowen [69]. | ||||||||

| TC_subsInfor_1 | The firm delivers information in a timely manner to employees like me within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.31 | 1.038 | −0.440 | −0.317 |

| TC_subsInfor_2 | The firm delivers relevant information to employees like me within the change. | 880 | 1 | 6 | 3.23 | 1.135 | −0.358 | −0.346 |

| TC_subsInfor_3 | The firm delivers complete information within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.12 | 1.178 | −0.275 | −0.685 |

| TC_subsInfor_4 | The firm delivers information that is not complicated for employees like me to comprehend within the change. | 880 | 1 | 6 | 3.05 | 1.237 | −0.234 | −0.773 |

| TC_subsInfor_5 | The firm delivers precise information to employees like me within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.01 | 1.265 | −0.243 | −0.85 |

| TC_subsInfor_6 | The firm delivers reliable information within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.37 | 0.949 | −0.118 | −0.293 |

| TC (Accountability); Rawlins [40], Men and Bowen [69]. | ||||||||

| TC_accontblty_1 | The firm presents multiple perspectives of controversial matters within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.73 | 0.817 | −0.922 | 1.208 |

| TC_accontblty_2 | The firm is disclosing information that might harm it within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.71 | 0.847 | −0.916 | 0.896 |

| TC_accontblty_3 | The firm accepts criticism by employees like me within the change. | 880 | 2 | 5 | 3.77 | 0.754 | −0.663 | 0.396 |

| TC_accontblty_4 | The firm freely acknowledges when it has made flaws within the change. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.74 | 0.826 | −1.045 | 1.489 |

| SL (Liden et al., 2014) | ||||||||

| SL_1 | My supervisor can determine if a work-related issue is going wrong. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.79 | 1.282 | −0.951 | −0.146 |

| SL_2 | My supervisor makes my career growth a priority. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.72 | 1.291 | −0.87 | −0.317 |

| SL_3 | I would ask help from my supervisor if I had a personal concern. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.74 | 1.282 | −0.894 | −0.224 |

| SL_4 | My supervisor affirms the significance of giving back to the community. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.74 | 1.290 | −0.918 | −0.217 |

| SL_5 | My supervisor puts my top interests ahead of his/her own. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.71 | 1.298 | −0.873 | −0.305 |

| SL_6 | My supervisor allows me to handle hard situations in a way that I believe is best. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.70 | 1.302 | −0.850 | −0.361 |

| SL_7 | My supervisor would NOT compromise moral values to achieve success. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.70 | 1.299 | −0.851 | −0.359 |

| Entrepreneurs’ resilience (Optimism); Connor and Davidson [75]. | ||||||||

| Optimisim1 | Things occur for a reason. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.41 | 1.003 | −0.454 | −0.422 |

| Optimism2 | I can deal with unpleasant emotions. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.48 | 0.996 | −0.833 | 0.143 |

| Optimism3 | I have to act on instinct. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.20 | 1.115 | −0.329 | −0.895 |

| Optimism4 | I have a solid feeling of purpose. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.38 | 1.067 | −0.522 | −0.641 |

| Optimism5 | I see the amusing side of things. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.06 | 1.117 | −0.213 | −0.998 |

| Optimism6 | I tend to rebound after a hardship or illness. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.51 | 1.087 | −0.855 | −0.018 |

| Optimism7 | Adapting to stress strengthens me. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.18 | 1.161 | −0.358 | −0.926 |

| Optimism8 | I devote my best effort, no matter what. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.22 | 1.116 | −0.435 | −0.814 |

| Optimism9 | Sometimes fate or God’s will can help. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.25 | 1.079 | −0.567 | −0.628 |

| Entrepreneurs’ resilience (Hardiness); Connor and Davidson [75]. | ||||||||

| Hardiness1 | Under stress, I concentrate and think clearly. | 880 | 2 | 5 | 4.31 | 0.8507 | −0.998 | 0.023 |

| Hardiness2 | When issues seem hopeless, I do not quit. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 4.29 | 0.8651 | −1.003 | 0.128 |

| Hardiness3 | I can handle whatever comes my way. | 880 | 2 | 5 | 4.28 | 0.872 | −0.953 | −0.096 |

| Hardiness4 | I can make uncommon or hard decisions. | 880 | 2 | 5 | 4.32 | 0.874 | −1.080 | 0.187 |

| Hardiness5 | I like to take the lead in problem-solving. | 880 | 2 | 5 | 4.30 | 0.875 | −1.022 | 0.076 |

| Hardiness6 | I believe I am a strong person. | 880 | 2 | 5 | 4.28 | 0.900 | −1.028 | 0.029 |

| Hardiness7 | I am not easily discouraged by failure. | 880 | 2 | 5 | 4.29 | 0.882 | −0.988 | −0.029 |

| Hardiness8 | I like challenges. | 880 | 2 | 5 | 4.28 | 0.896 | −1.036 | 0.093 |

| Hardiness9 | I work to achieve my goals. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 4.29 | 0.890 | −1.030 | 0.120 |

| Entrepreneurs’ resilience (Learning from Failure) Shepherd et al. [48] | ||||||||

| LE_Fail_1 | I have learned to better perform my duties. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 4.06 | 1.156 | −1.119- | 0.428 |

| LE_Fail_2 | I can more effectively execute my tasks. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 4.03 | 1.154 | −1.076 | 0.354 |

| LE_Fail_3 | I have developed my capability to make significant contributions to my job. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 4.01 | 1.157 | −1.036 | 0.263 |

| LE_Fail_4 | I can “recognize” earlier the indications that a project is in trouble. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 4.01 | 1.161 | −1.034 | 0.239 |

| LE_Fail_5 | I now understand the mistakes we did that resulted in the project’s failure. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 4.05 | 1.519 | 7.378 | 0.224 |

| LE_Fail_6 | I am more interested in helping others handle their failures. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.99 | 1.169 | −1.026 | 0.237 |

| LE_Fail_7 | I am a better tolerant person at work. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.99 | 1.168 | −1.020 | 0.231 |

| Adaptive performance (Individual task adaptivity); Griffin et al. [53]. | ||||||||

| Indv_Tsk_Adpt_1 | Coped well to changes in main duties. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.72 | 1.256 | −0.619 | −0.740 |

| Indv_Tsk_Adpt_2 | Adapted to changes to the way you must do your main tasks. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.69 | 1.263 | −0.594 | −0.763 |

| Indv_Tsk_Adpt_3 | Learned new capabilities to assist you cope with changes in your main tasks. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.69 | 1.261 | −0.588 | −0.769 |

| Adaptive performance (Team member adaptivity) Griffin et al. [53]. | ||||||||

| Tem_Memb_Adpt_1 | handled effectively changes influencing your work unit (e.g., new members). | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.61 | 0.921 | −0.722 | 0.612 |

| Tem_Memb_Adpt_2 | Learnt new capabilities or taken on new roles to adapt to changes in the way your unit operates. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.66 | 0.875 | −0.646 | 0.577 |

| Tem_Memb_Adpt_3 | Responded productively to changes in the way your team operates. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.58 | 0.930 | −0.686 | 0.280 |

| Adaptive performance (Organization member adaptivity) Griffin et al. [53]. | ||||||||

| Org_Memb_Adpt_1 | Responded flexibly to total changes in the firm (e.g., changes in management). | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.68 | 1.236 | −0.532 | −0.847 |

| Org_Memb_Adpt_2 | Adapted to changes in the way the firm operates. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.66 | 1.223 | −0.526 | −0.814 |

| Org_Memb_Adpt_3 | Learnt capabilities or gained information that assisted in adjusting to overall changes in the firm. | 880 | 1 | 5 | 3.64 | 1.226 | −0.485 | −0.860 |

| Dimensions and Items | Loading | C_R | AVE | MSV | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Employee resilience (a = 0.918) | 0.921 | 0.795 | 0.223 | 0.892 | ||||

| Optimism | 0.880 | |||||||

| Hardiness | 0.93 | |||||||

| Learning from failure. | 0.860 | |||||||

| 2-SL (a = 0.985) | 0.985 | 0.903 | 0.204 | 0.262 | 0.950 | |||

| SL1 | 0.953 | |||||||

| SL2 | 0.956 | |||||||

| SL3 | 0.972 | |||||||

| SL4 | 0.945 | |||||||

| SL5 | 0.948 | |||||||

| SL6 | 0.938 | |||||||

| SL7 | 0.940 | |||||||

| 3-TC (a = 0.930) | 0.948 | 0.860 | 0.316 | 0.225 | 0.225 | 0.927 | ||

| Participation | 0.926 | |||||||

| Substantiality information | 0.853 | |||||||

| Accountability | 0.932 | |||||||

| 4-Adaptive performance (a = 0.950) | 0.951 | 0.865 | 0.223 | 0.351 | 0.204 | 0.394 | 0.930 | |

| Individual task adaptivity | 0.820 | |||||||

| Team member adaptivity | 0.800 | |||||||

| Organization member adaptivity | 0.760 | |||||||

| Hypotheses | Beta (β) | C-R (T-Value) | R2 | Hypotheses Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | SL | → | Employee Resilience | 0.43 *** | 7.588 | Supported | |

| H2 | TC | → | Employee Resilience | 0.39 *** | 6.362 | Supported | |

| H3 | SL | → | Adaptative Performance | 0.27 *** | 3.461 | Supported | |

| H4 | TC | → | Adaptative Performance | 0.25 *** | 3.160 | Supported | |

| H5 | Employee Resilience | → | Adaptative Performance | 0.52 *** | 9.999 | Supported | |

| H6 | SL → Employee Resilience → Adaptative Performance | Path 1: β = 0.43 *** Path 2: β = 0.52 *** | Path 1: t-value = 7.588 Path 2: t-value = 9.999 | Supported | |||

| H7 | TC → Employee Resilience → Adaptative Performance | Path 1: β = 0.39 *** Path 2: β = 0.52 *** | Path 1: t-value = 3.160 Path 2: t-value = 9.999 | Supported | |||

| Employee Resilience | 0.34 | ||||||

| Adaptative Performance | 0.41 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshaer, I.A.; Saad, S.K. Learning from Failure: Building Resilience in Small- and Medium-Sized Tourism Enterprises, the Role of Servant Leadership and Transparent Communication. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215199

Elshaer IA, Saad SK. Learning from Failure: Building Resilience in Small- and Medium-Sized Tourism Enterprises, the Role of Servant Leadership and Transparent Communication. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):15199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215199

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Ibrahim A., and Samar K. Saad. 2022. "Learning from Failure: Building Resilience in Small- and Medium-Sized Tourism Enterprises, the Role of Servant Leadership and Transparent Communication" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 15199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215199

APA StyleElshaer, I. A., & Saad, S. K. (2022). Learning from Failure: Building Resilience in Small- and Medium-Sized Tourism Enterprises, the Role of Servant Leadership and Transparent Communication. Sustainability, 14(22), 15199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215199