Abstract

Previous research reports inconsistency in the relationship between political identity and orientations toward green consumption, and there is little information on the change mechanism(s) that link(s) political orientations and sustainable consumption behavior. In this study, we examine the mediating role of green values and beliefs about sustainability with respect to the relationship between a person’s political identity and personal values and his or her sustainable consumption behavior. Using structural equation modeling, the model was tested using data from an online survey of 179 adults. Results suggest that the effects of political identity and personal values on sustainable consumption behavior are mediated by green values and specific beliefs about sustainability, with conservatives being the least likely to adopt sustainable consumption habits. The findings also suggest that public policy makers attempting to persuade conservatives to adopt sustainable consumer behaviors may face an uphill task because deep-rooted values of conservatives might prevent them from accepting such messages in the belief formation stage. Implications of these findings for theory development and social scientists are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Global warming is now acknowledged to be a major global issue that is caused by human activity and will impact humanity in the long run. The Climate Change 2021 report presented by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change unequivocally stated that global warming is caused by human activity [1]. It is also acknowledged by scientists that a change in human behavior can potentially stop the trend in global warming and could potentially reverse its negative impacts. Such an approach would involve a major change in human behavior with respect to almost all activities, including how we work, entertain, and live our day-to-day lives. Sustainable consumption has also attracted the attention of scholars in a wide range of academic disciplines, including economics, business, design, and consumer behavior, and there has been a surge in the number of studies published on sustainable consumption in recent years (see [2,3,4,5] for some reviews). At the time of writing of this paper, a search of Business Source Premier with keywords “sustainable consumption” resulted in 1533 hits, and the same search on Science Direct resulted in 5884 hits.

Many definitions of sustainable consumption have been offered by scholars in various fields. Sustainable consumption can be defined as “a form of consumption that is compatible with the safeguard of the environment for the present and for the next generation. It is a concept that ascribes to consumers the responsibility or co-responsibility for addressing environmental problems through adoption of environmentally friendly behaviors” [5] (p. 4827). One widely accepted definition of sustainable consumption was presented at the Oslo symposium in 1994: “the use of services and related products, which respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life while minimizing the use of natural resources and toxic materials as well as the emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle of the service or product so as not to jeopardize the needs of future generations” [6].

The widely accepted concept of sustainability is based on three pillars or dimensions that represent how three aspects of society (social, economic, and environmental) interact with each other and can lead to sustainable development [7]. Although various authors have used different forms of graphical representation of this idea (e.g., three intersecting circles, three concentric circles, and three “pillars” supporting sustainability), the key idea contained in all such representations is that sustainable development is achievable by incorporating interaction and mutually supporting economic, social, and environmental goals.

Although many researchers have used the term “sustainable consumption” interchangeably with green consumption [8], we recognize that green consumption represents only one dimension (the environmental dimension) of sustainable consumption. Because the objective of this research is to focus on factors that contribute to behaviors related to sustainability and to simplify discussion of related issues, the two terms will be used interchangeably in this paper. A change in consumer behavior in line with sustainable consumption is both a macro political issue and an issue at the individual level. Sustainable consumption is affected by political issues at both the national and global levels, as well as at the individual political orientation level. Whereas nations of the world discuss and negotiate strategies and targets to achieve carbon neutrality [9], political forces within countries also influence national policies and the behavior of individuals. However, the core of any behavioral change at the societal level is based on individual consumers’ personal values, beliefs, and political orientations. For example, there is a rich body of literature about the effect of political ideology and personal values on behavior [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. In this context, Soderbaum [17] argues that the traditional “economic man” model needs to be modified to incorporate roles people play as citizens, with their political orientations serving as guiding principles driving values and behavior. He refers to this models as the “Political Economic Man” [17]. Whereas studies have been conducted on the relationship between political ideology and consumer behavior, the area has been less than adequately investigated, and additional research is needed [18].

There has been relatively little research on the relationship between political ideology and orientations toward green consumption. Existing research falls short of demonstrating the extent to which these variables are linked, how they are linked, and, most importantly, why they are linked, i.e., the mechanism or process(es) linking them. For example, whereas some researchers have found a positive relationship between liberal political orientations and green consumption attitudes and behavior [19,20], others have found no relationship between political orientation and green consumption [8]. Inconsistency in findings reported in the literature could be attributed to the possible mediating role of other variables. However, it has been recognized that there is a need to understand the mechanisms through which political ideology influences sustainable consumption [21].

Personal values have often been suggested as mediating variables [22]. However, there is a lack of clarity with respect to how values in general and green values in particular influence green-oriented purchase behavior [23]. Although scholars have studied consumer behavior related to the purchase of renewable energy [24], green building [25], and broad categories of consumer goods [26], as noted by Chwialkowska and Flicinska-Turkiewicz, there is a scarcity of research on green behaviors that do not involve purchase (e.g., electricity and energy conservation and recycling) [27]. As such, in the present research, we attempt to bridge this gap in the sparse literature.

The objective of this research is to test the mediating role of green values and beliefs about the environment with respect to the relationship of political orientations and personal values with sustainable consumption behaviors. In a review of the literature, Sivapalan et al. [14] noted that although research evidence to suggests a relationship between personal values and green consumption behavior and between consumption values and green consumption, no empirical research has examined the relationship between personal values and consumption values in relation to green consumption. The aim of the present research is to bridge this gap by developing a model of how personal values may indirectly influence sustainable consumption behavior through the mediating role of green values and sustainability-related environmental beliefs and sustainability-related social beliefs. This research also bridges the second gap in our understanding about the indirect influence of political identity on sustainable consumption behavior through the mediating role of green values and sustainability-related environmental beliefs and sustainability-related social beliefs.

In the following sections, we first develop and present a model of the relationships between political identity, personal values, green values, sustainability-related beliefs, and sustainable consumption. Specific hypotheses and theoretical support for these relationships are first presented, followed by an empirical study testing the model and the hypotheses. Finally, findings of this research are discussed, along with their implications for theory and practice.

2. Theoretical Perspectives

The self-identity and personal values theoretical frameworks are used to develop the model for the present study. Although these two theoretical frameworks, which are briefly discussed in the sections that follow, may appear to be independent, they are related in the sense that both influence an individual’s thoughts and actions.

2.1. Political Identity

The first theoretical framework that applies to the model of sustainable consumption is based on the notion of personal identity and its role in influencing sustainable consumption behavior. The concept of political identity is derived from the theories of self and self-identity [28,29]. The development of self-identity is based on self-categorization or identification. Self-identity can be complex, multidimensional, and contextual, helping to define the relationships people have with others within groups and with members of other groups [30]. Within the field of political psychology, self-identity has been defined as “something about who persons are in deep psychological sense” [31] (p. 32). Social identity theory has been widely used to understand the origin, nature, and dynamics of social identity among members of various groups [32]. As such, broadly speaking, self-identity represents the ways in which people view themselves. People may also assign certain characteristics or attributes to themselves or accentuate the salience of certain attributes as a part of their self-identity to create a persona within their own cognitive system. This persona can have a strong influence on a person’s thoughts and behaviors [33].

Based on the general concept of self, political identity has been defined as “a person’s self-conception based on their ideology regarding the underlying goals and ideals about how a social and political system should work” [34] (p. 55). Although membership in specific political parties, voting for candidates belonging to specific parties, and/or participation in specific political activities are often associated with political identities, these are not necessary conditions for the development of or identification with a political identity [34]. Unlike social identity, which may be ascribed at birth (e.g., race or national origin), some of the key attributes that distinguish political identity include that it is acquired, and most people have the freedom to acquire the identity they desire [33]. Political identity can also be considered to be a subset of self-concept [35]. Scholars and mass media have generally represented political identity on a left–right continuum. The origins of the left–right metaphor to represent political ideologies can be traced back to the French Revolution [34]. Irrespective of the origin of the left–right metaphor to represent political ideologies, it has stronger meaning in terms of the ideological differences between the two ends of the continuum. Those who identify themselves on the left end of the continuum have more liberal ideological orientation, and those who identify themselves with the right end of the continuum have a more conservative orientation [34]. Individuals with liberal orientation are generally open to change, and those with conservative orientation prefer traditional methods or stability and resist change [34]. For example, Duhachek, Tormala, and Han [36] reported that conservatives are more attracted to products when they are framed as providing stability, whereas liberals are more attracted to products when they are framed as providing change.

Several scholars have identified correlates of political identity [34]. For example, political identity has been found to be associated with personality characteristics [37,38]; specific motivations [39]; belief systems [40]; moral foundations [41,42]; complaining behavior [43]; brand attachment [44]; and attitudes toward specific policies, candidates, actions, and products [34]. Political identity has also been found to be associated with sustainable consumption behavior [20,45]. However, people who align with the left end of the continuum may shift their identity toward the right and vice versa in response to personal experiences, environmental changes, changes in statements/actions of specific politicians, or shifts in priorities set by specific political leaders or parties.

Willingness to change and preference for traditional methods may also help to identify similarities between political identity and personal values. As previously noted, one of the key attributes that characterizes differences between political ideologies is the notion of willingness to change. Similarly, as modeled by Schwartz [46,47], clusters of personal value can be plotted on two dimensions: the “willingness to change” dimension and the dimension of the so-called “pro-self–pro-social continuum.” As such, the willingness to change dimension may represent the common thread that ties together the two independent variables used in the present research to build a model of sustainable consumption behavior. The notion of sustainable consumption is tied to changes in consumption behaviors. The present model of consumption, based on the traditional Western practice of wasteful consumption, is pointed to by many as the root cause of many environmental problems faced by the world today. Proponents of green consumption contend that a change in our consumption behavior is needed to prevent or delay the onset of environmental disaster that we would otherwise encounter if the status quo is maintained.

2.2. Personal Values

The second aspect of the model is based on theories of personal values and their effects on specific behavior. Rokeach [48] defined values as “enduring belief that a specific mode of conduct or end-state of existence is personally or socially preferable to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end-state existence” (p. 5). He grouped core human values into instrumental values and terminal values. Terminal values reflect an end state that individuals might want to achieve, and instrumental values reflect means of achieving the desired end state. Based on these notions, Schwartz [46,47] further grouped values into ten clusters that characterize individual differences. These ten clusters can be plotted on two dimensions [47]. The first of these two dimensions represents the pro-self—pro-social continuum, and the second dimension represents the willingness to change—preservation of tradition continuum. All ten clusters identified by Schwartz [46,47] can be placed on these two dimensions. When applied to the behavior of individuals as consumers, values can also be considered to represent social cognitions that guide responses to specific marketing stimuli [49].

Irrespective of the framework used to understand or classify values, they also represent an underlying motivational force that directs individuals to act in certain ways. However, values may not directly influence behavior. It has been argued that the effects of values on specific behaviors is mediated by corresponding beliefs, attitudes, and intentions [50]. Within the area of sustainable consumption behavior, there is empirical evidence to suggest that values are related to green consumption, albeit indirectly [51,52,53].

In line with the above-cited research, the proposed model of sustainable consumption posits that general personal values influence specific green consumption values. Green consumption values, in turn, influence specific beliefs related to sustainable consumption and sustainable consumption behavior. Thus, the model presented in the following section focuses on the mechanisms through which political identity and personal values may influence individuals’ sustainable consumption behavior.

3. Model and Hypotheses

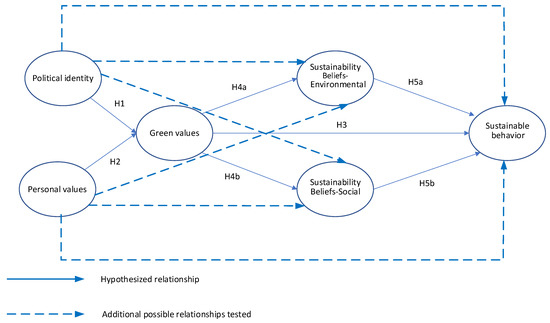

Figure 1 presents a model of the effects of political identity and personal values on sustainable consumption behavior. It shows how political identity and personal values can affect behavior both directly and indirectly via the mechanisms of sustainable beliefs by influencing green values. Although previous research shows relationships between political identity and personal values, the mechanisms that link these factors to sustainable consumption remain relatively unexplored. Some of the proposed relationships between specific variables are built on existing theory, whereas other relationships are deduced from empirical findings and tend to be exploratory. Theoretical and empirical justifications for proposed relationships are discussed in the paragraphs that follow.

Figure 1.

A Model of political identity, personal values, green values, sustainability-related beliefs, and sustainable consumption behavior.

3.1. Political Identity and Consumption Behavior

Political identity has been found to be associated with a wide range of behaviors in general, and those associated with green consumption in particular. For example, Wright et al. [54] found that political ideology is a predictor of involvement in crime. Jung et al. [43] found that political ideology influences complaining behavior and reactions to resolutions offered by companies, with conservatives being less likely to complain and less likely to dispute resolutions offered by companies than liberals. Many researchers have reported relationships between political ideology and a wide range of behaviors, such as decisions and choices [44,55,56], brand associations [44], complaining behavior [43], green behaviors [57], variety-seeking behavior [58], hedonic purchase behavior [59], and private label and new product patronage behaviors [55]. Madani, Seenivasan, and Ma [18] found a relationship between store patronage behavior and political ideology.

Political orientations and political identity have been associated with specific consumption behaviors. For example, Gromet et al. [60] found that politically liberal individuals are more likely to favor investing in energy-efficient products. Considering green consumption behavior as a special aspect of consumer behavior, past research has also focused on the relationship between political identity and green consumption behavior. For example, Watkins, Aitkin, and Mather [21] found that liberal orientation influences political involvement, and political involvement in turn influences deep-green behaviors. However, these researchers did not find a direct link between liberal orientation and deep-green behaviors (or mid-green behaviors), possibly because other variables mediate the relationship between political orientation and green consumption behaviors. Therefore, it is important that we understand the mechanisms through which political orientations influence sustainable behavior.

It is our contention that political identity influences green behaviors through green consumer values. There is a close relationship between political identity and values, as the former is also defined in terms of the values that people hold. For example, Certutti [61] stated that, “Political identity is, first, the set of social and political values and principles that we recognize as ours, or in the sharing of which we feel like ‘us’, like a political group or entity” (p. 26). As such, it can be assumed that these values will have an effect on values people hold with respect to green consumption. Based on the above arguments we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1:

Political identity is related to green consumption values, with conservative orientations negatively associated with such values.

3.2. Personal Values

Values are related to sustainable consumption. For example, values such as universalism, benevolence, self-direction, responsibility, and freedom are positively related to sustainable consumption, whereas values of power, security, hedonism, and tradition are negatively related to sustainable consumption [62,63]. Collectivist values [64] and altruistic values [46] are also related to sustainable consumption. Halder et al. [65] found that planning and collectivist culture are positively related to green consumption values, whereas traditional values are negatively related to green consumption values.

In a review of the literature, Sivapalan et al. [14] cited research that shows a positive relationship between core personal values and green consumption values. Green consumption values, in turn, are positively related to green behavioral intentions. However, they also noted that more empirical research is needed to test for the relationships and the mechanisms that drive these relationships. Considering that green values can be assumed to be a specific case of personal values, an argument can be made that the effect of core personal values on sustainable consumption is mediated through green values. As such, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2:

A person’s strength of core positive personal values drawn from benevolence, universalism, and hedonism clusters is positively related to the strength of the person’s green consumption values.

3.3. Green Consumption Values

Green consumption values are defined as “the tendency to express the value of environmental protection through one’s purchases and consumption behaviors” [66] (p. 337). Haws et al. also state that green values represent a part of “larger nomological network associated with conservation of not just environmental resources but also personal financial and physical resources” [66] (p. 337). Since the development of the GREEN scale by Haws, Winterich, and Naylor [66], many researchers have examined its antecedents and outcomes. There is a significant amount of evidence to suggest that green consumer values are positively related to green consumer behaviors [67], and these values are also reported to influence consumers’ response to companies’ communication efforts [68].

Based on a review of the literature, Testa et al. [5] identified seven types of variables that they called “drivers to green consumption”. Each type of variable or driver, in turn, incorporates several variables that have been studied as antecedents of sustainable consumption. The key drivers identified by Testa et al. [5] are sociodemographic variables; intrapersonal values—environment, interpersonal values—non-environment, personal capabilities, and behavioral factors (including past behaviors and habits); marketing-related factors; and contextual factors. Of interest in the present study are values that can influence sustainable consumption behavior because they can help us understand the mechanisms through which such values might influence sustainable consumption.

Hypothesis 3:

The strength of a person’s green consumption values is positively related to the extent of their sustainable consumption behaviors.

3.4. Antecedents of Sustainable Consumption

An argument can also be made to suggest an indirect relationship between green consumer values and sustainable consumption behavior based on the general model of how values influence behavior. As documented by several researchers, general values lead to attitudes that, in turn, lead to intentions and behavior [69,70]. In line with this argument, do Paco et al. [67] found a positive relationship between green consumer values and general prosocial attitudes, asserting that general prosocial attitudes precede specific green consumer values. However, this view is not consistent with the general model of values, attitudes/norms, intentions, and behavior [71]. It is our contention that general broad personal values lead to specific green values, which lead to attitude formation specific to green consumption. However, instead of focusing on the formation of attitudes, we examine beliefs (as components of attitudes) related to green consumption values. This argument is in line with Stern et al.’s finding [70] that biospheric–altruistic values are positively related to beliefs about environmental conditions to the extent that they are related to self, others, and other species in the biosphere.

Hypothesis 4:

A person’s strength of green consumption values is positively related to his or her level of (a) sustainability-related environmental beliefs and (b) sustainability-related social beliefs.

3.5. Beliefs and Sustainable Consumption Behavior

Several scholars have examined the relationship between attitudes toward sustainable consumption and sustainable consumption behavior. However, many researchers report inconsistent results [63,72]. Whereas some researchers report a positive relationship between attitudes and behavior [73,74,75,76], others report a negative or no relationship between the two. For example, Trivedi, Patel, and Acharya [77] found that whereas inward environmental attitudes are positively related to intentions to purchase green products, outward environmental attitude was not related to such intentions. A lack of relationship or a weak relationship between the two has also been termed as the attitude–behavior gap with respect to sustainable consumption.

In the present study, we argue that inconsistent findings and the existence of the “attitude–behavioral intention” gap may be due to the nature of attitudes and other factors that influence intentions and behavior [63]. According to the theory of reasoned action [78], attitudes represent a composite measure of beliefs and their relative importance. Moreover, because behavioral intentions are based on attitudes, and subjective norms (comprised of beliefs about opinions of specific referents, and motivations to comply), it is possible that an internal conflict (e.g., between attitudes and subjective norms or between beliefs and motivations to comply with specific referents) might result in confounded relationships that have lower predictive value than pure beliefs. Therefore, in the present model, we incorporate the mediating role of specific beliefs relating to sustainability (environmental and social) as predictors of sustainable consumption behavior. Empirical evidence supports this line of reasoning. For example, Lu, Chang, and Chang [79] found a positive relationship between beliefs about recycling and green buying intentions. Similarly, Goh and Balaji [80] found a positive relationship between subjective environmental knowledge and green purchase intentions, whereas Stern et al. [70] found that biospheric and ego-related beliefs were positively related to behavioral intentions to engage in pro-environmental actions.

Hypothesis 5:

A person’s (a) sustainability-related environmental beliefs and (b) sustainability-related social beliefs are positively related to sustainable consumption behaviors.

4. Methods

4.1. Data Collection

Data for the study were collected using an online survey developed on the Qualtrics platform. It was a part of a larger survey focused on food and sustainable aspects of consumption. The sample was drawn from the panels maintained by a research firm, Cloud Research (www.cloudresearch.com (accessed on 18 January 2021), which operates a participant-sourcing platform that is designed for researchers seeking participants for their studies. The survey was made available to eligible panel members (U.S. residents 18 years of age and older), and all participants who provided responses that satisfied quality checks were compensated in a manner and amount in line with the agreement with the panel owners. Cloud Research was paid its normal fees for providing platform services, which included compensation to participants. A total of 354 responses were received. Of these, 83 responses failed the quality checks (response to quality check question, rushed responses) and were not considered for further analysis. Additionally, responses that did not have complete data for all items included in this study were excluded from the analysis (listwise deletion). A total of 179 valid responses were complete and were used in the study (male = 45.8%, mean age = 48.85 years). All participants were residents of the United States. The demographic profile of the sample is presented in Appendix A. Although the sample was diverse in terms of demographic characteristics, it was a convenience sample and not representative of total U.S. population. Almost one-fifth of the participants (21.2%) were 66 years of age or older, and another 21.2% were between 56 years and 65 years of age. Among younger participants, 8.9% were 25 years of age or younger, 16.2% were between 26 years and 35 years, 19.6% were between 36 years and 45 years, and 12.3% were between 46 years and 55 years of age. In terms of education, 2.8% of participants reported having less than high school education, 28.5% reported having completed high school, 19.0% reported having completed some college but no degree, and another 11.7% reported earning an associate degree. Finally, 23.5% percent reported having a bachelor’s degree, and another 14.5% reported having a master’s degree or higher level of education. In terms of income, almost three out of ten participants (29.1%) reported earning USD 25,000 or less per year, and another one out of four (25.1%) reported earning between USD 25,001 and 50,000 per year. The proportion of those with higher earnings levels was relatively small, with 9.5% reporting an income between USD 50,001 and 75,000 and another 9.5% reported an income between USD 75,001 and 100,000. Only, 6.7% reported an income of more than USD 150,000. Finally, in terms of racial diversity, a vast majority of participants (78.2%) reported being white or Caucasian. Other racial groups were also represented in the sample: Black or African American (10.6%), Hispanic or Latino origin (6.1%), Asian American or Pacific Islander (5.6%), American Indian or Alaska native (2.2%), and others (2.8%). Whereas this sample cannot be considered to be representative of the total U.S. population, the sample is diverse, not idiosyncratic, and can be considered acceptable for hypothesis testing. Moreover, sample size should not be a hindrance because simulation-based studies have shown that samples as small as 150 or less could be acceptable for studies based on structural equation models [81,82].

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Political Identity

Political identity was measured by asking respondents to indicate on five-point scales (1 = much more in favor of liberals, 5 = much more in favor of conservatives) the extent to which their views on social issues, economic issues, and general issues (e.g., the role of government and international relations) are in favor of policies proposed by so-called liberals or so-called conservatives. The three items were derived from the work of Jung and Mittal [35]. The responses to the three items were summed to obtain an overall measure of political identity on the 3-to-15-point measure (alpha = 0.96). As such, a higher score on the political identity scale would reflect a conservative orientation, and a lower score on the scale would reflect a liberal orientation. Specific party names were not mentioned in the questionnaire. It is possible that someone who identifies with liberal orientation voted for a Republican candidate or someone who identifies with conservative orientation and voted for a Democratic candidate. Descriptive statistics and the reliability of all scales are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scale statistics and reliabilities.

4.2.2. Personal Values

Personal values refer to four personal values: self-respect, warm relationship with others, sense of belonging, and fun and enjoyment in life. These four select values correspond with benevolence, universalism, and hedonism clusters identified by Schwartz [47]. These clusters are in the openness to change and self-transcendence quadrants of the model identified by Schwartz. They have also been documented to be related to sustainable consumption [65]. Additionally, these are positive values that most individuals in Western society aspire to hold. Each of the four values was measured by asking respondents to indicate on a five-point scale (5 = extremely important, 1 = not at all important) the extent to which the personal values are important to them. The core values measure was obtained by summing up responses to the four items, producing a 4-to-20-point overall measure. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability of this scale was 0.74.

4.2.3. Green Consumption Values

Green consumption values were measured using the scale developed by Haws, Winterich, and Naylor [66]. The scale has six items measured on a five-point Likert scale (5 = strongly agree, 1= strongly disagree). The alpha reliability of the scale was 0.93.

4.2.4. Sustainability-Related Beliefs

Sustainability-related beliefs were measured using a modified version of items from the scale developed by Balderjahn et al. [83]. The original scale has nine items representing two dimensions (environmental consciousness and social consciousness) and incorporating both beliefs and their respective importance. Only the belief items were used in this study. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with statements reflecting their beliefs related to sustainable consumption on a five-point Likert scale (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree). Of the five items in the social dimension, one item did not correlate well with remaining items and was dropped from the analysis. The reliability of the two dimensions of beliefs about sustainable consumption was 0.96 and 0.93 for environmental and social dimensions, respectively.

4.2.5. Sustainable Consumption Behavior

Sustainable consumption behavior was measured using six items drawn from the list of behaviors developed by Panno et al. [20]. The original list has 17 items. However, all items are not culturally or socially applicable to all societies. Moreover, some items do not apply to all segments of the population (e.g., “sometimes I buy clothing at secondhand stores” and “I prefer to bike to school instead of driving”). As such, all 17 items were factor-analyzed. Six items from the list loaded on the first factor and collectively explained 19.90% of the variance. The selected items are listed in Appendix B. The reliability of the final scale of six items was 0.69.

4.3. Test of Social Desirability Bias

To test for the possibility of social desirability influencing responses to the items used in the study, social desirability response bias was assessed, and its correlations were examined with the variables used in the study. Although it can be assumed that sustainable consumption is socially desirable and some people may respond positively to measures used in the study because of their social desirability bias, this may be true only for those who consider sustainable consumption or other variables used in the study to be socially desirable. If they do not consider sustainable consumption to be desirable, we would expect either no relationship between measures of social desirability and the variable being examined or a negative relationship being between the two. To test for social desirability bias, responses to the scales for personal values, green consumption values, sustainability-related environmental beliefs, sustainability-related social beliefs, and sustainable consumption behavior were compared with the modified short version of the balanced inventory of desirable responding scale (BIDR) [84] (alpha = 0.744). A review of the correlations suggested that the BIDR scale was not related to green consumption values (r = 0.005, n.s.), sustainability-related environmental beliefs (r = −0.019, n.s.), sustainability-related social beliefs (r = −0.051, n.s.), and sustainable consumption behavior (r = 0.078, n.s.). Personal values were negatively related to BIDR (r = −0.169, p < 0.05). The negative relationship between BIDR and personal values suggests that people were not concerned about social desirability in expressing their personal values.

Because the scale about political identity measured identity (conservative or liberal), it can be assumed that whatever position a person takes, he/she would consider it to be socially desirable. However, to check whether responses to political identity were biased due to social desirability, the sample was divided into those who indicated their identity to be conservative (scored high on the political identity scale, n = 59) and those who indicated their political identity to be liberal (scored low on the political identity scale, n = 61). The remaining 59 participants had scored in the midpoint of the political identity scale and were not considered in this analysis. BIDR was not related to either conservatives (r = −0.129, n.s.) or to liberals (r = −0.066, n.s.). This lack of relationship between BIDR and the political identity scale suggests that participants were not concerned about social desirability when they indicated their political identity. Therefore, it can be safely concluded that social desirability did not influence responses to items on the scales used in this study.

4.4. Test of Discriminant Validity

The discriminant validity of all constructs used in the model was tested using the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio method suggested by Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt [85]. This method is based on the principle of the multitrait–multimethod matrix (MTMM) and is reported to have several advantages compared with methods based on variance often used as a part of structural equation modelling. HTMT ratios between all combinations of constructs used in the model were below unity and satisfied the HTMT0.90 criterion recommended by Gold, Malhotra, and Segars [86] and Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt [85], demonstrating the discriminant validity of constructs used in the model. HTMT ratios among all variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

HTMT ratios.

4.5. Results

The first step of the analysis involved testing the measurement model with all manifest variables loading on their respective latent variables as reflective indicators and all latent variables allowed to correlate freely. The results of this measurement model indicate that the model fit the data well (χ2 = 454.39, df = 308, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.052, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.956, normed fit index (NFI) = 0.876, non-normed fit index (NNFI) = 0.940, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.0534). Additionally, all factor loadings on their respective latent variables were significant and ranged from 0.435 to 0.964 (Table 3). Factor loadings reflect the proportion of variance in each indicator that is explained by the factor. Factor loadings of items for all scales except for that of the sustainable consumption scale were high and acceptable. Loadings for items used in the scale for sustainable consumption were lower than those for other items, possibly because a wide range of behaviors can be included within the scope of sustainable consumption, and a limited number of behaviors may not capture the totality of behaviors related to sustainable consumption.

Table 3.

Factor loadings.

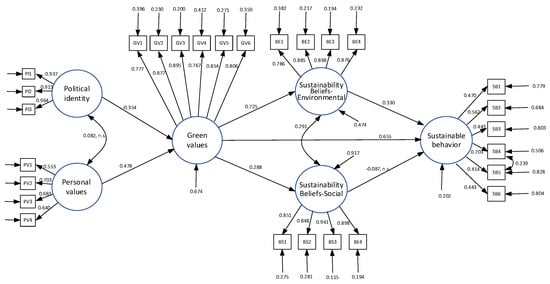

The second step of analysis involved testing the model, as shown in Figure 1. Assessment of the overall fit of the model was also based on multiple indicators. Initial results suggested that the model fit the data well (χ2 = 481.41, df = 315, RMSEA = 0.054, CFI = 0.950, NFI = 0.868, NNFI = 0.944, and SRMR = 0.0584). However, an examination of modification indices suggested that the overall fit of the model could be improved if the error terms for two indicators of the sustainable consumption behavior were allowed to correlate. Therefore, two error terms were allowed to correlate. This improved the overall fit of the model. Fit indices of the final model suggested that the data fit the model well (χ2 = 461.353, df = 314, χ2/df = 1.469, RMSEA = 0.051, CFI = 0.955, NFI = 0.874, NNFI = 0.950, and SRMR = 0.056). For example, a χ2/df ratio of less than 2.0, an NNFI value of 0.95, and RMSEA value of less than 0.08, and an SRMS value of less than 0.08 suggest a good fit of the model [87].

Parameter estimates for hypothesized relationships are given in Table 4, and all parameter estimates are given in Appendix C. Hypothesis 1 suggested that conservative political identity would be negatively related to green consumption values. This hypothesis was supported by the data (maximum likelihood estimate = −0.354, t-value = −4.750). Hypothesis 2 suggested that personal values would be positively related to green consumption values. This hypothesis was supported by the data (maximum likelihood estimate = 0.478, t-value = 5.663). Hypothesis 3 suggested that green consumption values would be positively related to sustainable consumption behaviors. This hypothesis also was supported by the data (maximum likelihood estimate = 0.655, t-value = 4.546). Hypothesis 4a suggested that green consumption values would be positively related to sustainability-related environmental beliefs. This hypothesis was supported by the data (maximum likelihood estimate = 0.725, t-value = 8.605). Hypothesis 4b suggested that green consumption values would be positively related to sustainability-related social beliefs. This hypothesis was also supported by the data (maximum likelihood estimate = 0.288, t-value = 3.625). Hypothesis 5a suggested a positive relationship between sustainability-related environmental beliefs and sustainable consumption behavior. This hypothesis was supported by the data (maximum likelihood estimate = 0.330, t-value = 2.632). Finally, hypothesis 5b suggested that sustainability-related social beliefs would be positively related to sustainable consumption behavior. This hypothesis was not supported by the data (maximum likelihood estimate = −0.087, t-value = −1.117).

Table 4.

Parameter estimates.

An argument can be made that political identity is directly related to sustainability-related beliefs and sustainable consumption behavior. For example, formation of beliefs about sustainability may be related to information received from politically driven sources as a form of learning. As such, it can be claimed that education is related to beliefs with respect to climate change (for or against). However, it has been observed that for conservatives, this relationship may not hold true. Hess and Maki [88] theorize that for conservatives, beliefs related to climate change may not directly relate to educational attainment. They built a model showing how political beliefs may influence beliefs related to climate change based on selective exposure bias and resistance to belief change. They found evidence to support their contention that selective exposure bias may prevent conservative students from taking courses that cover topics related to climate change. Moreover, even when such courses are taken, resistance to change may play a role in preventing them from using obtained knowledge to change their beliefs. Similarly, an argument can be made for direct paths from personal values to sustainability-related environmental beliefs, sustainability-related social beliefs, and sustainable behaviors. Therefore, to test for the possibility of these direct relationships between the two independent variables and dependent variables included in the model, the direct paths from political identity and personal values to these variables were set free, and the revised model was estimated again. The revised model resulted in insignificant improvement in the overall fit of the model (Δχ2 = 6.965, Δdf = 6). Furthermore, none of the direct paths from political identity and personal values to mediating variables (sustainability-related beliefs) and the dependent variable (sustainable consumption behavior) were significant. This confirms the possible mediating role of green consumption values and beliefs in the relationship between political identity and sustainable consumption behaviors.

5. Discussion

Before substantively interpreting of the findings of this research, it is important to highlight several limitations of the present study. Although the structural equation modelling research methodology and the model tested imply a causal relationship, it is important to note that in any cross-sectional study, observed relationships do not imply causal relationships but merely associations between variables. Second, all variables in the study were measured at the same time. As such, there is a possibility of common method bias [89], although multiple steps were taken to ensure data quality and reduce the possibility of bias. Third, although data used for this study exhibited adequate variance in terms of study variables, it was based on a convenience sample. Future researchers may attempt to gather a representative sample and test whether the relationships found in this research hold true for the total U.S. population. Moreover, in this study, we examined the situation as it exists in the United States; given different countries have different political systems, and citizens have varying levels of freedom to express their political ideology, future researchers may attempt to test for these relationships in other countries. Another limitation of the present study was the below-threshold level of reliabilities (composite reliability and average variance extracted) of the three variables, although Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities were acceptable. As noted by Nunnally [90], reliabilities below the minimum levels are acceptable for new measures, although future researchers should seek improvements in the measures used in the present study. Finally, in this study, we examined the effect of personal values and political ideology on sustainable consumption. The obtained results represent a limited view of factors that might influence sustainable consumption or moderate the relationships presented in the model. As such, this study does not represent a comprehensive model of all possible factors that play a role in sustainable consumption. Despite the limitations, findings of this research should be of interest to various parties, warranting further explication.

The findings confirm that green consumption values and sustainability-related beliefs play a mediating role in the relationship between political identity and personal values and sustainable consumption behavior. These findings have important implications for social scientists, policy makers, and researchers.

Public opinion surveys [91] and some research studies [20,21] have presented evidence that those who identify as conservatives are less likely to support sustainability-related policies or engage in sustainability-related behaviors. In this study, we present a model to explain the reason for this relationship, in addition to presenting a plausible reason as to why it might be difficult to convince conservatives to adopt sustainability-related causes.

For social scientists, this research suggests a mechanism through which political identity influences specific behavior. Past research has presented evidence about the relationship between political identity and various aspects of consumer behavior [60]. However, there has been a paucity of research that explains the reason(s) or the mechanisms through which political identity might influence consumer behavior. In this research, we present one such explanation. This research shows that political identity does not exert a direct influence on sustainable behaviors. However, it exercises an indirect influence through green consumption values and beliefs about sustainability.

Considering the negative effects of global warming, public policy makers may want to use various strategies to persuade citizens to adopt sustainable consumption practices. Rewarding environmentally friendly behaviors via tax credits on purchases of energy-efficient products and leaving high taxes on products that harm the environment are strategies along these lines. An example of the latter strategy can be seen in the New Zealand government’s proposed tax on greenhouse gas emissions related to farm animals as part of its efforts to reduce the pollution that is causing climate change. This research shows that there might be pitfalls in developing strategies to persuade people to change, as well as some opportunities that can be capitalized on. Considering the important and indirect role of political identity, different approaches might be necessary for conservatives and liberals. Policy makers attempting to persuade conservatives to adopt sustainable consumption behaviors may face an uphill task because deep-rooted values of conservatives might prevent them from accepting such persuasive messages in the belief formation stage. These messages could be filtered out through mechanisms related to selective perception. For any strategy to work in this area, it might be appropriate to target deep-rooted values. Policy makers might attempt to first de-link political identity and green values by communicating to the conservative audience that, for example, holding green values is not a manifestation of political identity. However, this might be an uphill task. As long as vested interests continue to link political identity with green values, it may be difficult to persuade people to separate the two.

However, policy makers attempting to persuade liberals to adopt sustainable consumption behaviors may find an audience that is willing to change. With a value system that is consistent with willingness to change and accept new ideas, this target audience may be ready to accept communication messages focused on the formation of beliefs related to sustainability (environmental and social). Such beliefs, in turn, can persuade liberal consumers to adopt sustainable consumption behaviors.

Future researchers may seek opportunities to establish causal relationships among the variables used in this study. Demonstration of causal relationships would lend credibility to strategies to improve sustainable consumption based on these findings. Future researchers may also consider testing for these relationships across different cultures. Although different nations have different political structures, the distinction between conservative political thinking and liberal political thinking may have wider appeal across nations. As such, mechanisms through which individuals with different political leanings (conservative or liberal) may be applicable across nations.

Besides being able to help explain the mechanisms though which political identity influences sustainable consumption behavior, this research is subject to some limitations. The study was based on a convenience sample. As such, researchers should exercise caution in applying the findings to the total population of the United States. Future studies may collect data from representative samples to test whether such relationships hold true for the whole population. Considering the fact that the liberal–conservative divide in society might exist in many countries, future researchers may collect data from different countries to see whether these relationships hold true in other parts of the world.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that political identity does not directly influence sustainable consumption behaviors. Rather, the influence of political identity on such behaviors is indirect and mediated through green values and beliefs. As previous research has indicated, values are deep-rooted and difficult to change. However, they can change in response to cultural, environmental, and social changes [69]. Environmental changes related to global warming and environmental degradation might encourage liberals to accept information about threats to sustainability and form corresponding beliefs. However, the same deep-rooted values among conservatives might prevent them from accepting information related to sustainability and forming corresponding beliefs. These beliefs, in turn, influence sustainable consumption behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P.M. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.M. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, G.P.M. and A.M.; funding acquisition, G.P.M. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by a grant from the Frank G. Zarb School of Business to the first author. The APC was funded by G.P.M.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the home institution of the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Demographic Profile of the Sample.

Table A1.

Demographic Profile of the Sample.

| N = 179 (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Up to 25 years | 8.90 |

| 26 to 35 years | 16.20 |

| 36 to 45 years | 19.60 |

| 46 to 55 years | 12.30 |

| 56 to 65 years | 21.60 |

| 66 years or older | 21.20 |

| Sex | |

| Male (%) | 45.80 |

| Female (%) | 54.20 |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 2.80 |

| High school graduate | 28.50 |

| Some college but no degree | 19.00 |

| Associate degree in college (2 years) | 11.70 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 23.50 |

| Master’s degree or higher | 14.5 |

| Income | |

| Up to USD 25,000 | 29.10 |

| USD 25,001 to 50,000 | 25.10 |

| USD 50,001 to 75,000 | 14.50 |

| USD 75,001 to 100,000 | 9.50 |

| USD 100,001 to 125,000 | 9.50 |

| USD 125,001 to 150,000 | 5.60 |

| More than USD 150,000 | 6.70 |

| Race | |

| White or Caucasian | 78.20 |

| Black or African American | 10.60 |

| Hispanic (Hispanic or Latino origin) | 6.10 |

| Asian-American or Pacific Islander | 5.60 |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 2.20 |

| Other | 2.80 |

Note: respondents could select more than one race category.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Items used to measure constructs in the model. Political identity (all items measured on a 5-point scale: 1 = much more in favor of liberals, 2 = more in favor of liberals, 3 = neither or no opinion, 4 = more in favor of conservatives, 5 = much more in favor of conservatives).

Table A2.

Items used to measure constructs in the model. Political identity (all items measured on a 5-point scale: 1 = much more in favor of liberals, 2 = more in favor of liberals, 3 = neither or no opinion, 4 = more in favor of conservatives, 5 = much more in favor of conservatives).

| Variable Name | Statement |

| PI1 | Nowadays we hear a lot about things the government could do to improve peoples’ quality of life. To what extent are your views on proposed policies regarding SOCIAL ISSUES in favor of policies proposed by the so-called “liberals” or by those of “conservatives”? |

| PI2 | Nowadays we hear a lot about things the government could do to improve peoples’ quality of life. To what extent are your views on proposed policies regarding ECONOMIC ISSUES in favor of policies proposed by the so-called “liberals” or by those of “conservatives”? |

| PI3 | To what extent are your views on proposed policies regarding GENERAL ISSUES (e.g., role of government, international relations, etc.) in favor of policies proposed by the so-called “liberals” or by those of “conservatives”? |

| Personal values (measured on a 5-point scale: 5= extremely important to me, 1 = not at all important to me). | |

| Variable Name | Value |

| PV1 | Self-respect |

| PV2 | Warm relationship with others |

| PV3 | Sense of belonging |

| PV4 | Fun and enjoyment in life |

| Green consumption values (measured on a 5-point scale: 5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree). | |

| Variable Name | Value |

| GV1 | It is important to me that the products I use do not harm the environment |

| GV2 | I consider the potential environmental impact of my actions when making many of my decisions |

| GV3 | My purchase habits are affected by my concern for our environment |

| GV4 | I am concerned about wasting the resources of our planet |

| GV5 | I would describe myself as environmentally responsible |

| GV6 | I am willing to be inconvenienced in order to take actions that are environmentally friendly |

| Sustainability-related beliefs: environmental (measured on a 5-point scale: 5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree). You would buy a product only if you believe that (during the manufacture). | |

| Variable Name | Belief |

| BE1 | It is made from recycled materials |

| BE2 | It can be disposed of in an environmentally friendly manner |

| BE3 | It is packaged in an environmentally friendly manner |

| BE4 | It is produced in an environmentally friendly manner |

| Sustainability-related beliefs: social (measured on a 5-point scale: 5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree). You would buy a product only if you believe that (during the manufacture). | |

| Variable Name | Belief |

| BS1 | No illegal child labor is involved |

| BS2 | Workers are not discriminated against |

| BS3 | Workers are not abused |

| BS4 | Workers are treated fairly or are compensated |

| Sustainable consumption behavior (measured on a 5-point scale: 5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | |

| Variable Name | Behavior |

| SC1 | I regularly recycle paper, plastic, and metal |

| SC2 | I prefer to use recycled paper when I can |

| SC3 | I use reusable shopping bags |

| SC4 | I often talk with friends or strangers about environmental issues |

| SC5 | I often attend environmental rallies |

| SC6 | I usually prefer to eat vegetables than meat |

Appendix C

Figure A1.

SEM Model and Parameter Estimates. Note: Values presented in the model are maximum likelihood estimates for corresponding parameters. All parameters are significant (p < 0.05), except for those marked with “n.s.”.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2021. The Physical Science Basis. 2021. Report. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Bray, J.; Johns, N.; Kilburn, D. An exploratory study into the factors impeding ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, H.R.; Panni, M.F.A.K.; Orphanidou, Y. Factors affecting consumers’ green purchasing behavior: An integrated conceptual framework. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2012, 14, 50–69. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/168746 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Milfont, T.L.; Markowitz, E. Sustainable consumer behavior: A multilevel perspective. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Pretner, G.; Iovino, R.; Bianchi, G.; Tessitore, S.; Iraldo, F. Drivers to green consumption: A systematic review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4826–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Sustainable Consumption & Production. Available online: https://enb.iisd.org/topics/sustainable-consumption-production (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R. The taste for green: The possibilities and dynamics of status differentiation through “green” consumption. Poetics 2013, 41, 294–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. COP26 The Glasgow Climate Pact. Available online: https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/COP26-Presidency-Outcomes-The-Climate-Pact.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Crockett, D.; Wallendorf, M. The role of normative political ideology in consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, D.N.; Waldron, I. Attitudes toward cohabitation, family, and gender roles: Relationships to values and political ideology. Sociol. Perspect. 1997, 40, 199–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccas, S.; Sagiv, L. Personal values and behavior: Taking the cultural context into account. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2010, 4, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, A.K.; Rowe, A.J.; Bird, S.; Powers, S.; Legault, L. Motivational orientation explains the link between political ideology and proenvironmental behavior. Ecopsychology 2016, 8, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapalan, A.; von der Heidt, T.; Scherrer, P.; Sorwar, G. A consumer values-based approach to enhancing green consumption. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swigart, K.L.; Anantharaman, A.; Williamson, J.A.; Grandey, A.A. Working while liberal/conservative: A review of political ideology in organizations. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 1063–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, A.D. Personal values and the direction of behavior. Sch. Rev. 1942, 50, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderbaum, P. Political economic person, ideological orientation and institutional change. J. Interdiscip. Econ. 2021, 12, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, F.; Seenivasan, S.; Ma, J. Determinants of store patronage: The roles of political ideology, consumer and market characteristics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E. The impact of political orientation on environmental attitudes and actions. Environ. Behav. 1975, 7, 428–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, A.; Carrus, G.; Brizi, A.; Maricchiolo, F.; Giacomantonio, M.; Mannetti, L. Need for cognitive closure and political ideology. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 49, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L.; Aitken, R.; Mather, D. Conscientious consumers: A relationship between moral foundations, political orientation and sustainable consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, M. New insights into socially responsible consumers: The role of personal values. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunden, C.; Atis, E.; Salali, H.E. Investigating consumers’ green values and food-related behaviours in Turkey. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanimann, R.; Vinterbäck, J.; Mark-Herbert, C. Consumer behavior in renewable electricity: Can branding in accordance with identity signaling increase demand for renewable electricity and strengthen supplier brands? Energy Policy 2015, 78, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Y.K.; Hsu, Y.H.; Xie, X. Identifying customer behavioral factors and price premiums of green building purchasing. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 64, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Bohlen, G.M.; Diamantopoulos, A. The link between green purchasing decisions and measures of environmental consciousness. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, A.; Flicinska-Turkiewicz, J. Overcoming perceived sacrifice as a barrier to the adoption of green non-purchase behaviours. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, G.J.; Simmons, J.L. Identities and Interactions; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.C.; Hogg, M.A.; Oakes, P.J.; Reicher, S.D.; Wetherell, M.S. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Basil Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.M. Intersecting Voices: Dilemmas of Gender, Political Philosophy, and Policy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997; ISBN-13: 978-0691012018. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981; ISBN-13: 978-0521280730. [Google Scholar]

- Huddy, L. From social to political identity: A critical examination of social identity theory. Political Psychol. 2001, 22, 127–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Mittal, V. Political identity and the consumer journey: A research review. J. Retail. 2020, 96, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Urminsky, O. The role of causal beliefs in political identity and voting. Cognition 2019, 188, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhachek, A.; Han, D.; Tormala, Z.L. Stability vs. change: The effect of political ideology on product preference. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Cotte, J., Wood, S., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2014; Volume 42, pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Vecchione, M.; Fraley, C.R. Voters’ personality traits in presidential elections. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, D.R.; Jost, J.T.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. The secret Lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychol. 2008, 29, 807–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Glaser, J.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Sulloway, F.J. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckitt, J.; Wagner, C.; Du Plessis, I.; Birum, I. The psychological bases of ideology and prejudice: Testing a dual process model. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Haidt, J.; Nosek, B.N. Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 1029–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidt, J.; Graham, J. When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Soc. Justice Res. 2007, 20, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Garbarino, E.; Briley, D.A.; Wynhausen, J. Blue and red voices: Effects of political ideology on consumers’ complaining and disputing behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.Y.; Ilicic, J. Political ideology and brand attachment. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2019, 36, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Hardisty, D.J.; Habib, R. The elusive green consumer. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 11, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973; ISBN-13: 978-0029267509. [Google Scholar]

- Kahle, L.R. Social values and consumer behavior: Research from the list of values. In The Psychology of Values: The Ontario Symposium; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996; Volume 8, pp. 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; De Groot, J.I.M. Environmental values. In The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology; Clayton, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2012; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; von Borgstede, C.; Biel, A. Willingness to accept climate change strategies: The effect of values and norms. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Value structures behind proenvironmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Effects of values, problem awareness, and personal norm on willingness to reduce personal car use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.P.; Beaver, K.M.; Morgan, M.A.; Connolly, E.J. Political ideology predicts involvement in crime. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 106, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Misra, K.; Singh, V. Ideology and brand consumption. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavitt, S. Political ideology drives consumer psychology: Introduction to research dialogue. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 500–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, B.; Farmer, A.; Hardesty, D.M. Getting liberals and conservatives to go green: Political ideology and congruent appeals. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D.; Mandel, N. Political conservatism and variety-seeking. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, A.; Kidwell, B.; Hardesty, D.M. The politics of choice: Political ideology and intolerance of ambiguity. J. Consum. Psychol. 2021, 31, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromet, D.M.; Kunreuther, H.; Larrick, R.P. Political ideology affects energy-efficiency attitudes and choices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9314–9319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerutti, F. A political identity of the Europeans? Thesis Elev. 2003, 72, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, D.G. Values and their effect on pro-environmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 1996, 28, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer attitude–behavioral intention gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Collectivism and individualism as cultural syndromes. Cross-Cult. Res. 1993, 27, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Hansen, E.N.; Kangas, J.; Laukkanen, T. How national culture and ethics matter in consumers’ green consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Paço, A.; Shiel, C.; Alves, H. A new model for testing green consumer behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.A.; Mishra, A.S.; Tiamiyu, M.F. Application of GREEN scale to understanding US consumer response to green marketing communications. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, L.R.; Xie, G.-X. Social values in consumer psychology. In Handbook of Consumer Psychology; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 576–586, ISBN-13: 978-0-8058-5603-3. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Kalof, L.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. Values, beliefs, and proenvironmental action: Attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 1611–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olli, E.; Grendstad, G.; Wollebaek, D. Correlates of environmental behaviors: Bringing back social context. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Investigating the determinants of consumers’ sustainable purchase behaviour. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2017, 10, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozar, J.M.; Connell, K.Y.H. Socially and environmentally responsible apparel consumption: Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Soc. Responsib. J. 2013, 9, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Mohamad, M.R.; Yaacob, M.R.B.; Mohiuddin, M. Intention and behavior towards green consumption among low-income households. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 227, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, C.; Kast, S.W. Promoting sustainable consumption: Determinants of green purchases by Swiss consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.H.; Patel, J.D.; Acharya, N. Causality analysis of media influence on environmental attitude, intention and behaviors leading to green purchasing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.-C.; Chang, H.-H.; Chang, A. Consumer personality and green buying intention: The mediate role of consumer ethical beliefs. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.K.; Balaji, M.S. Linking green skepticism to green purchase behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderjahn, I.; Buerke, A.; Kirchgeorg, M.; Peyer, M.; Seegebarth, B.; Wiedmann, K.-P. Consciousness for sustainable consumption: Scale development and new insights in the economic dimension of consumers’ sustainability. AMS Rev. 2013, 3, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C.M.; Ritchie, T.D.; Hepper, E.G.; Gebauer, J.E. The balanced inventory of desirable responding short form (BIDR-16). Sage Open 2015, 5, 2158244015621113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.J.; Maki, A. Climate change belief, sustainability education, and political values: Assessing the need for higher-education curriculum reform. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Tyson, A. On Climate Change, Republicans Are Open to Some Policy Approaches, Even as They Assign the Issue Low Priority, Pew Research Center. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/07/23/on-climate-change-republicans-are-open-to-some-policy-approaches-even-as-they-assign-the-issue-low-priority/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).