What Makes People Pay Premium Price for Eco-Friendly Products? The Effects of Ethical Consumption Consciousness, CSR, and Product Quality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Characteristics of Eco-Friendly Products

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2.1. Theoretical Premises

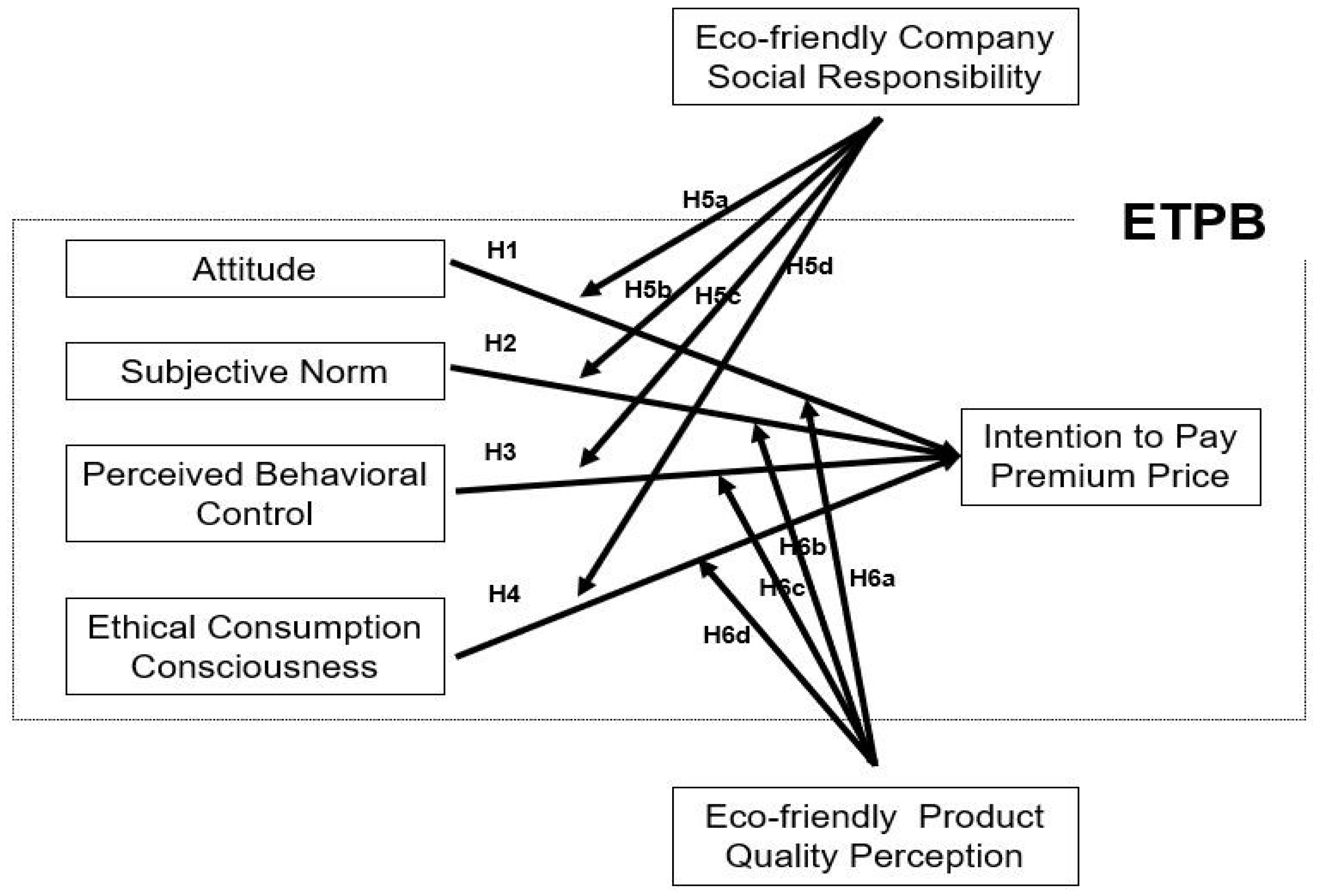

2.2.2. Extended Theory of Planned Behavior

2.3. Intention to Pay Premium Price

2.4. Research Hypotheses

2.4.1. Attitude of Eco-Friendly Product and Intention to Pay Premium Price

2.4.2. Subjective Norm of Eco-Friendly Product and Intention to Pay Premium Price

2.4.3. Perceived Behavioral Control of Eco-Friendly Product and Intention to Pay a Premium Price

2.4.4. Ethical Consumption Consciousness and Intention to Pay a Premium Price

2.4.5. Eco-Friendly Company’s Social Responsibility

2.4.6. Eco-Friendly Product’s Quality Perception

3. Research Methods and Materials

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Scale Measures and Operational Definition

3.3. Data Collection

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. General Characteristics of the Sample Respondents

4.2. Results of Validity and Reliability Tests

4.3. Correlations

4.4. Hypotheses Verification

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Summary and Discussions on Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications for Sustainable Business Strategies

5.4. Recommendations and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demirbas, A. Future energy sources. In Waste Energy for Life Cycle Assessment; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 33–70. [Google Scholar]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, P. A Socio-economic Indicator for EoL Strategies for Bio-based Products. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 178, 106794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, P. Exploring Regional Transitions to The Bioeconomy Using A Socio-Economic Indicator: The Case of Italy. Econ. Politica 2022, 39, 989–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhomme, P.; Cristea, M.; Paran, F. Self-reported frequency and perceived difficulty of adopting eco-friendly driving behavior according to gender, age, and environmental concern. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 2013, 20, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henion, K.E. Ecological Marketing; Grid: Columbus, OH, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Albino, V.; Balice, A.; Dangelico, R.M. Environmental strategies and green product development: An overview on sustainability-driven companies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, S. Green Marketing Consumer Attitude Towards Eco-Friendly Fast Moving Household Care and Personal Care Products. Ph.D. Dissertation, Manav Rachna International University, Faridabad, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.H.; Jeong, H.J. Measuring the Effects of Belief, Subjective Norm, Moral Feeling and Attitude on Intention to Consume Organic Beef. J. Korean Soc. Food Cult. 2008, 23, 301–307. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Muhmin, A.G. Explaining consumers? willingness to be environmentally friendly. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2006, 31, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberlein, T.A. Navigating Environmental Attitudes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuther, T.L. Rational decision perspectives on alcohol consumption by youth: Revising the theory of planned behavior. Addict. Behav. 2002, 27, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C. Theory of Planned Behavior: Potential Travelers from China. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2004, 28, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Ryu, K.S. Exploring Customer’s Visit Intention towards Solo Restaurant: The Application of Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Foodserv. Manag. Soc. Korea 2014, 17, 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Intentional Social Action in Virtual Communities. J. Interact. Mark. 2002, 16, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, M.J. Predicting Foreign Tourists’ Goal-Directed Adoption Intention toward a New Type of Korean Quick Service Restaurant. Ph.D. Dissertation, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lajunen, T.; Räsänen, M. Can social psychological models be used to promote bicycle helmet use among teenagers? A comparison of the Health Belief Model, Theory of Planned Behavior and the Locus of Control. J. Saf. Res. 2004, 35, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behaviour: A case study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P. Intention—Behavior Relations: A Conceptual and Empirical Review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 12, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H.C. Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Dubinsky, A.J. The Theory of Planned Behavior in E-commerce: Making A Case for Interdependencies Between Salient Beliefs. Psychol. Mark. 2005, 22, 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, J.; Schmidt, P.; Ajzen, I. Birth Control Versus AIDS Prevention: A Hierarchical Model of Condom Use among Young People1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 27, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Y.J. Research Models Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior for Predicting Foreign Tourists’ Behavior toward Korean Wave Cultural Contents: Focused on Korean Soap Operas and Records. Ph.D. Dissertation, Sejong University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The Role of Desires and Anticipated Emotions in Goal-Directed Behaviors: Broadening and Deepening the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Lee, C.K. A Study on the Decision-Making Process of Ski Resort Visitors using Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Acad. Korea Hosp. Tour. 2010, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, C.; Smith, S. Purchasing Habits of Senior Farmers’ Market Shoppers: Utilizing the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 30, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J. Developing a Tourist’s Responsible Tourism Intention Model Using a Theory of Planned Behavior. Ph.D. Dissertation, Dong-A University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, K.I.; Mohr, P.; Wilson, C.; Wittert, G.A. Determinants of fast-food consumption. An application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Appetite 2011, 57, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzell, R.D.; Gale, B.T. The PIMS Principles: Linking Strategy to Performance; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, A.R.; Bergen, M.E. Price Premium Variations as a Consequence of Buyers’ Lack of Information. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, S.; Pavlou, P.A. Evidence of the Effect of Trust Building Technology in Electronic Markets: Price Premiums and Buyer Behavior. MIS Q. 2002, 26, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C. Does Doing Good Always Lead to Doing Better? Consumer Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going green To Be Seen: Status, Reputation, and Conspicuous Conservation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J.F.; Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W. Consumer Behavior, 8th ed; The Dryden Press: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, B. The Mediation Effect of Outdoor Recreation Participation on Environmental Attitude-Behavior Correspondence. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, P.J.; Scott, K. Environmental concern and behaviour in an Australian sample within an ecocentric—anthropocentric framework. Aust. J. Psychol. 2006, 58, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E.; Martinez, E. Environmental values and lifestyles as determining factors of ecological consumer behaviour: An empirical analysis. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, J.; Jacob, J. Green Marketing: A Study of Consumers’ Attitude towards Environment Friendly Products. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Sheikh, S. Action versus inaction: Anticipated affect in the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyvaert, V. Regulatory Competition--Accounting for the Transnational Dimension of Environmental Regulation. J. Environ. Law 2012, 25, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizer, K.; Schultz, P.W. Social Norms and Pro-Environmental Behaviour. In Environmental Psychology: An Introduction; Steg, L., de Groot, J.I.M., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, H.; Dijksterhuis, A. The Silence of the Library: Environment, Situational Norm, and Social Behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizer, K.; Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. The Spreading of Disorder. Science 2008, 322, 1681–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A.; Matthies, E.; Höger, R. Responsibility and Environment Ecological Norm Orientation and External Factors in the Domain of Travel Mode Choice Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 830–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior; Dorsey Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.; Huang, S. An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior Model for Tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 36, 390–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Driver, B.L. Prediction of leisure participation from behavioral, normative, and control beliefs: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Leis. Sci. 1991, 13, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T.J.; Ellen, P.S.; Ajzen, I. A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.G.; Song, I.S. A Case Study of Ethical Consumer in Korea. J. Consum. Cult. 2010, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.A. The Married Women’s Proenvironmental Consumer Behavior. Ph.D. Dissertation, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.J.; Peter, A.D. The Company and the Product: Corporate Associations and Consumer Product Responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, X.M.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Satisfaction, and Market Value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, R.; Cotte, J. Does it pay to be good? MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2009, 50, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Huh, K.O. The style of consumers’ purchase, consumers’ attitudes toward environment and proenvironmental behavior. Korean J. Hum. Ecol. 2004, 13, 569–579. [Google Scholar]

- Peattie, K. Green Marketing; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1992; pp. 11–47. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J.T. The Effect of Consumers’ Perception of Green Certificates on Environmental Responsibility, Corporate Image and Purchasing Intention of Small and Medium Enterprises. Ph.D. Dissertation, Seoul University of Venture, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gwak, N.S. A Study on the Improvement of the Carbon Footprint Label on Food in Korea, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. Health Welf. Policies Forum 2011, 172, 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.Y. The Effects of the Eco-friendly Products on the Quality Perception and Purchase Behavior Focused on the Higher Eco-friendly Value Group, Korea E-Trade Research Institute. Electron. Trade Res. 2013, 11, 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring Service Quality: A Reexamination and Extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitturi, R.; Raghunathan, R.; Mahajan, V. Delight by Design: The Role of Hedonic versus Utilitarian Benefits. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martín, J.D.; Quintana, A. A model of customer loyalty in the retail banking market. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.L. Simultaneous-Equation Model for Estimating Consumer Risk Perceptions, Attitudes, and Willingness-to-Pay for Residue-Free Produce. J. Consum. Aff. 1993, 27, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.L.; McCluskey, J.J.; Mittelhammer, R.C. Will Consumers Pay A Premium for Eco-Labeled Apples? J. Consum. Aff. 2002, 36, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.J. Impacts of Consumer’s Innovation and Value on Eco-Friendly Product Purchase Intention and Purchas. Ph.D. Dissertation, Sejong University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Karp, D.G. Values and their effect on pro-environmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 1996, 28, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J. The Effects of Green Consumers’ Characteristics on Company Image and Purchase Intention of Green Marketing Sport Products Companies. Ph.D. Dissertation, Sookmyong Women’s University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Castaldo, S.; Perrini, F.; Misani, N.; Tencati, A. The Missing Link Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumer Trust: The Case of Fair Trade Products. J. Bus. Ethic. 2008, 84, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Kim, N.M.; Yoo, K.H.; Lee, M.K. Developing a Scale for Evaluating Corporate Social Responsibility. Korea Mark. Rev. 2005, 20, 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, P.; Li, C.G. Research on College Students’ Sense of Environmental Protection and Consumption Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 6, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.J. A Study on the Moderating Effect of Knowledge of the Environment Issues on Consumption Values Regarding Eco-friendly Fashion Products; Focused on University Students. J. Korea Des. Forum 2015, 49, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J. The Effect of Eco-Friendly University Students’ Environmental Consciousness and Behaviors on Eco-tourism Participation Intention. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2013, 14, 6211–6217. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S. Testing the effects of reciprocal norm and network traits on ethical consumption behavior. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 32, 1611–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.G. Environmentally conscious consumption behavior according to lifestyle of green consumers. J. Korean Data Anal. Soc. 2005, 7, 997–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.; Kim, Y. The Effect of University Student Consumer Values, Environmental Knowledge, and Environmental Involvement on Environmental Conscious Behavior. Consum. Culture Res. 2007, 10, 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Goo, H.K. The effect of consumer citizenship on ethical corporate attitudes, ethical consumption, and consumer loyalty. Corp. Manag. Rev. 2018, 9, 251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.M.; Yoon, S.J. A Study on the Behavior of Consumer Citizenship on Corporate Ethics Management Activities and Consumer Loyalty. Res. Commod. Stud. 2016, 34, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, W.S.; Yoon, S.J.; Kim, N.M. The effect of a company’s CSR image on product attitude and purchase intention: The mediating and regulating role of consumer citizenship and control focus. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 14, 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.M.; Yoon, S.J. The effect of customer citizenship in company social responsibility (CSR) activities on purchase intention: The important role of the CSR image. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Measurement | Item | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude of eco-friendly product | Overall level of perceptions regarding eco-friendly product formed by previous knowledge and awareness. | 11 | Yang (2014) [70] |

| Subjective Norm | Perception of other people’s opinions on and the degree of acceptance of eco-friendly purchase behavior. | 4 | Yang (2014) [70] |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | The level of control over action due to self-perception regarding having resources, such as time, money, and time, which facilitate a targeted behavior. | 3 | Ajzen(1988) [50] |

| Ethical Consumption Consciousness | The level of awareness toward ethical consumption behaviors based on social and ethical norms. | 5 | Karp (1996) [71], Kim (2012) [72] |

| Intention to Pay Premium Price | The degree of willingness to pay a higher price for a product purchase. | 3 | Castaldo et al. (2009) [73] |

| Eco-friendly Company’s Social Responsibility | The level at which consumers expect a company to perform social charity activities, regional and cultural events, environmental protection, and economic responsibility. | 12 | Kim et al. (2005) [74] |

| Quality Perception of Eco-friendly Product’s | The perceived quality level of an eco-friendly product is formed by the subjective judgment of the consumer. | 3 | Han (2013) [64] |

| Variable | Category | No. | % | Variable | Category | No. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 102 | 44 | Age | Under 20 | 8 | 3.4 |

| Female | 130 | 56 | Under 30 | 201 | 86.6 | ||

| For education level | High school graduates | 156 | 67.2 | Under 40 | 17 | 7.3 | |

| University graduates | 54 | 23.3 | Under 50 | 6 | 2.6 | ||

| Graduate degree | 22 | 9.5 | Occupation | Student | 204 | 87.9 | |

| Monthly income | Below 2 million won (approximately $700) | 197 | 84.9 | Office workers | 15 | 6.5 | |

| 2 million won–3 million won | 22 | 9.5 | Service professionals | 4 | 1.7 | ||

| 3 million won–4 million won | 9 | 3.9 | Managers | 2 | 0.9 | ||

| 4 million won–5 million won | 3 | 1.3 | Others | 7 | 3 | ||

| Over 5 million won | 1 | 0.4 | Total | 232 | 100 | ||

| Factor | Variables Items | Components | Extraction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| Attitude | Attitude 4 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.15 | −0.11 | 0.10 | 0.77 |

| Attitude 7 | 0.80 | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.71 | |

| Attitude 2 | 0.77 | −0.05 | −0.12 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.13 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.77 | |

| Attitude 6 | 0.75 | 0.11 | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.12 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.77 | |

| Attitude 3 | 0.74 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.27 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.75 | |

| Attitude 1 | 0.74 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.14 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.72 | |

| Attitude 11 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.15 | 0.17 | −0.08 | 0.72 | |

| Attitude 9 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 0.20 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.04 | 0.25 | −0.04 | 0.73 | |

| Attitude 5 | 0.70 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.72 | |

| Attitude 8 | 0.68 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.14 | 0.73 | |

| Attitude 10 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.00 | −0.09 | −0.05 | 0.25 | −0.21 | 0.69 | |

| Eco-friendly Company Social Responsibility | Responsibility 5 | −0.02 | 0.79 | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.08 | −0.02 | 0.65 |

| Responsibility 12 | −0.02 | 0.76 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.71 | |

| Responsibility 1 | 0.05 | 0.74 | −0.16 | 0.10 | −0.07 | −0.10 | 0.16 | −0.25 | 0.8 | |

| Responsibility 2 | −0.08 | 0.73 | −0.16 | 0.15 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.19 | −0.34 | 0.81 | |

| Responsibility 4 | 0.13 | 0.73 | −0.10 | 0.05 | 0.12 | −0.09 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.74 | |

| Responsibility 3 | 0.04 | 0.70 | −0.15 | 0.08 | −0.09 | −0.05 | 0.12 | −0.34 | 0.77 | |

| Responsibility 11 | 0.03 | 0.70 | 0.19 | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.7 | |

| Responsibility 8 | 0.08 | 0.69 | 0.24 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.73 | |

| Responsibility 9 | 0.12 | 0.68 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.6 | |

| Responsibility 7 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.11 | 0.29 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.76 | |

| Responsibility 10 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.17 | −0.08 | 0.22 | 0.69 | |

| Responsibility 6 | 0.17 | 0.64 | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.23 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.67 | |

| Intention to participate voluntarily | Consciousness 5 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.08 | 0.09 | −0.15 | 0.8 |

| Consciousness 4 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.71 | 0.07 | 0.21 | −0.17 | 0.10 | −0.13 | 0.8 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | Control 2 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.10 | 0.92 | −0.06 | 0.13 | −0.11 | −0.07 | 0.81 |

| Control 3 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.9 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.82 | |

| Control 1 | 0.14 | 0.11 | −0.13 | 0.73 | 0.16 | −0.17 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.76 | |

| ethical intention to consume | Consciousness 2 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.87 | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.82 |

| Consciousness 3 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.83 | 0.05 | 0.11 | −0.13 | 0.84 | |

| Consciousness 1 | 0.16 | 0.06 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.75 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.77 | |

| Eco-friendly Product Quality Perception | Quality Percept 2 | 0.09 | 0.16 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.09 | −0.05 | 0.83 |

| Quality Percept 1 | 0.01 | 0.20 | −0.12 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.76 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.82 | |

| Quality Percept 3 | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.06 | 0.72 | 0.19 | −0.12 | 0.77 | |

| Subjective Norm | Norm 4 | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.18 | 0.72 | −0.01 | 0.73 |

| Norm 3 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.69 | 0.10 | 0.83 | |

| Norm 2 | 0.24 | −0.02 | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.63 | 0.07 | 0.78 | |

| Norm 1 | 0.29 | −0.06 | −0.13 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.51 | −0.04 | 0.71 | |

| Intention to Pay Premium Price | Intention to Pay 2 | 0.17 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.18 | −0.06 | −0.68 | 0.80 |

| Intention to Pay 1 | 0.20 | −0.09 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.16 | −0.06 | −0.67 | 0.76 | |

| Intention to Pay 3 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.61 | 0.75 | |

| Eigenvalue | 17.7 | 3.85 | 2.01 | 1.83 | 1.63 | 1.45 | 1.24 | 1.08 | KMO. 0.94 Approx. Chi-Square 375.91 sig.0.00 | |

| Variance (%) | 43.36 | 9.39 | 4.90 | 4.47 | 3.98 | 3.53 | 3.03 | 2.63 | ||

| Total variance explained (%) | 43.36 | 52.75 | 57.65 | 62.12 | 66.10 | 69.63 | 72.66 | 75.28 | ||

| Cronbach a | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.89 | ||

| Division | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 1 | |||||||

| Norm | 0.71 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Control | 0.43 ** | 0.37 ** | 1 | |||||

| Intention to consume | 0.56 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.35 ** | 1 | ||||

| Intention to participate | 0.46 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.41 ** | 1 | |||

| Intention to Pay | 0.62 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.52 ** | 1 | ||

| Social Responsibility | 0.58 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.48 ** | 1 | |

| Quality Perception | 0.55 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.63 ** | 1 |

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.82 | |

| Attitude | 0.41 | 0.09 | 0.34 | 4.61 | 0.00 |

| Subjective Norm | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.53 |

| Perceived Behav Control | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.41 |

| Ethical Intention to consume | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 3.20 | 0.00 *** |

| Intention to participate | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 4.46 | 0.00 *** |

| Dependent variable: Intention to Pay | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p |

| Attitude (A) | 0.34 | 4.61 | 0.00 *** | 0.31 | 3.92 | 0.00 *** | 0.28 | 3.47 | 0.00 *** |

| Norm (B) | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.08 | 1.15 | 0.25 |

| Control (C) | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.53 | −0.03 | −0.49 | 0.63 |

| Ethical Intention to consume (D) | 0.19 | 3.20 | 0.00 *** | 0.19 | 3.11 | 0.00 *** | 0.27 | 4.32 | 0.00 *** |

| Intention to participate (E) | 0.25 | 4.46 | 0.00 *** | 0.23 | 4.15 | 0.00 *** | 0.19 | 3.42 | 0.00 *** |

| Social Responsibility (M) | 0.10 | 1.60 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 2.03 | 0.04 * | |||

| (A) × (M) | −0.26 | −2.65 | 0.01 * | ||||||

| (B) × (M) | 0.26 | 2.96 | 0.00 *** | ||||||

| (C) × (M) | −0.12 | −1.87 | 0.06 | ||||||

| (D) × (M) | 0.17 | 2.13 | 0.04 * | ||||||

| (E) × (M) | 0.10 | 1.47 | 0.14 | ||||||

| F-value | 42.01 | 35.68 | 23.09 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.54 | ||||||

| Change of R2 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.51 | ||||||

| Change of p | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p |

| Attitude (A) | 0.34 | 4.61 | 0.00 *** | 0.31 | 4.06 | 0.00 *** | 0.26 | 3.23 | 0.00 *** |

| Norm (B) | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.67 | 0.08 | 1.14 | 0.25 |

| Control (C) | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.79 | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.55 |

| Ethical Intention to consume (D) | 0.19 | 3.2 | 0.00 *** | 0.19 | 3.06 | 0.00 *** | 0.25 | 3.98 | 0.00 *** |

| Intention to participate (E) | 0.25 | 4.46 | 0.00 *** | 0.25 | 4.48 | 0.00 *** | 0.21 | 3.73 | 0.00 *** |

| Quality Perception (M) | 0.08 | 1.39 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 2.03 | 0.04 * | |||

| (A) × (M) | −0.3 | −2.76 | 0.01 * | ||||||

| (B) × (M) | 0.25 | 2.72 | 0.01 * | ||||||

| (C) × (M) | −0.02 | −0.32 | 0.75 | ||||||

| (D) × (M) | 0.17 | 2.15 | 0.03 * | ||||||

| (E) × (M) | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.53 | ||||||

| F-value | 42.01 | 35.47 | 21.85 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.52 | ||||||

| Change of R2 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.50 | ||||||

| Change of p | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Research Hypotheses | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Attitude of eco-friendly product will have a positive effect on intention to pay a premium price. | Accept |

| H2 | Subjective norm will have a positive effect on intention to pay a premium price for eco-friendly product. | Reject |

| H3 | Perceived behavioral control about eco-friendly product will have a positive effect on intention to pay a premium price. | Reject |

| H4 | Ethical consumption consciousness will have a positive effect on intention to pay a premium price for eco-friendly products. | Accept |

| H5a | Perceived social responsibility will moderate the relationship between attitude of eco-friendly product and intention to pay a premium price. | Accept |

| H5b | Perceived social responsibility will moderate the relationship between subjective norm and intention to pay a premium price. | Accept |

| H5c | Perceived social responsibility will moderate the relationship between perceived behavioral control and intention to pay a premium price. | Reject |

| H5d | Perceived social responsibility will moderate the relationship between ethical consumption consciousness and intention to pay a premium price. | Accept |

| H6a | Quality perception of eco-friendly product will moderate the relationship between attitude of eco-friendly product and intention to pay premium price. | Accept |

| H6b | Quality perception of eco-friendly product will moderate the relationship between subjective norm and intention to pay premium price. | Accept |

| H6c | Quality perception of eco-friendly product will moderate the relationship between perceived behavioral control and intention to pay premium price. | Reject |

| H6d | Quality perception of eco-friendly product will moderate the relationship between ethical consumption consciousness and intention to pay premium price. | Accept |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Z.Q.; Yoon, S.J. What Makes People Pay Premium Price for Eco-Friendly Products? The Effects of Ethical Consumption Consciousness, CSR, and Product Quality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315513

Sun ZQ, Yoon SJ. What Makes People Pay Premium Price for Eco-Friendly Products? The Effects of Ethical Consumption Consciousness, CSR, and Product Quality. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315513

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Zhao Qi, and Sung Joon Yoon. 2022. "What Makes People Pay Premium Price for Eco-Friendly Products? The Effects of Ethical Consumption Consciousness, CSR, and Product Quality" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315513