Abstract

In Australia, there is a significant health gap between rural and urban populations. One set of tools that could help lessen that gap is drones used for pharmaceutical delivery. There are extensive regulations surrounding the dispensing of prescription and controlled drugs, as well as strict requirements from aviation regulations for drone operators to meet. To assess and analyse the issues associated with operating at the intersection of pharmaceutical and aviation regulations in Australia, institutional theories can be applied. To inductively shed light on the key issues associated with the use of drones for the delivery of pharmaceuticals, a series of interviews were conducted using a truncated convergent interviewing approach. The common issues raised amongst experts highlight the complex challenge when developing drone networks for the delivery of pharmaceuticals. The main constraints appear to be due to aviation, not medication regulation. Legal grey areas, regulator inflexibility and other regulatory concerns stemming from strong institutional forces have created an environment limiting the use of drone delivery. Until drone regulations are changed, the potential of this innovative and developing sector is substantially restrained and those living in regional and rural areas will continue to have limited access to healthcare.

1. Introduction

In Australia, there is a significant health gap between regional and urban populations. On average, regional Australian men and women die eleven years and sixteen years earlier, respectively, than Australians in major cities [1]. Australians in very regional areas are also much more likely to be hospitalized for preventable conditions, the rate of which increases with the distance from urban areas [1]. One of the issues causing this ill health is a lack of qualified health professionals. Very regional areas have nearly half as many pharmacists as major cities [1]. In the absence of pharmacists, local health workers must take up that role [2].

Facing similar issues, several African and Pacific nations have deployed drones to improve medical access. Rwanda implemented a program that uses drones to deliver blood to regional hospitals, saving time and minimizing wastage [3]. Similarly, medical drone services have expanded across Africa and the Pacific [4], with Australian company Swoop Aero working on plans to introduce medicine delivery services in rural Queensland [5]. At the intersection of the pharmacy and aviation industries, medication delivery companies in Australia must deal with multiple regulators, each with established and stringent legal requirements.

Furthermore, the use of drone delivery, in this case for pharmaceuticals, from a logistics point of view can dramatically reduce the ‘last mile’ costs in rural areas, with reduced carbon emissions [6]. Some estimates from Korea suggest that drones emit 13 times less greenhouse gases than the equivalent motorbike and far less than a van [7]. Although the sustainability credentials of drones are still debated, particularly due to issues associated with recycling batteries [8], the advantage of drones over other delivery means can increase further when more of the electricity used is produced from renewable sources [7]. In general, whether for medication delivery or e-commerce, the use of drones needs a system-wide approach to transport sustainability [8].

In the specific case of the potential use of drones for medication delivery, possible service providers are facing two main sets of regulations. First, there is extensive regulation surrounding the dispensing of prescription and controlled drugs. Considerations for these laws include patient privacy, medication information and prescription transfer [9]. There are also considerations about the provision of controlled substances, such as pseudoephedrine, which requires a buyer to present photo-identification [10].

Second, the Australian aviation regulator, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA), has developed very strict requirements for drone operators to meet. Currently, operators are required to obtain a raft of approvals and certificates prior to commencing operations. To engage in commercial activities, companies are required to obtain a remote operator’s certificate [11]. For longer range operations, operators need to obtain Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) approval, allowing them to operate beyond visual range [12]. These approvals are essential for potential medication drone providers such as Swoop because their drones can travel distances over one hundred kilometers [13]. The BVLOS is a complex approval to obtain, with only a handful of companies achieving it since the first was issued in May 2021 [14]. Adding complexity, some companies produce custom designed drones for use in their commercial operations [15]. To use a large drone commercially, the drone must receive type approval from CASA, certifying that it is compliant with design regulations [16].

To assess and analyse the issues associated with the complexity of operating at the intersection of pharmaceutical and aviation regulations in Australia, institutional theories can be applied. Institutional theory studies how social structures and behavioural expectations form. Institutional theory explains the role of social influence and pressures for social conformity in shaping organizational action [17]. Competitive advantages are highly impacted at both the organization and inter-firm level by institutional context of resource decisions such as rules and societal norms [18]. Various elements of institutional theory can be used to explain the formation and dissolution of institutions, as well as how they shift and change over time.

Institutional theory suggests that organizations within a given field often mimic each other, taking up similar form and structure, operating under similar practices. Interestingly, these accepted and adopted structures do not always result in maximum efficiency [17].

Within organizations, institutional pressures manifest in terms of organizational culture and politics. At the inter-organizational level, institutions are influenced by regulatory and public pressures placed on organizations by various stakeholders [18]. These factors can culminate into isomorphism when viewed at an inter-organizational level, ultimately contributing to homogeneity among organizations.

Institutional change is often very subtle and only apparent over longer periods of time. Organizational activities and routines can be standard operating procedures and are dependent on the embeddedness within a task [19]. Actors (individuals or organizations) can slowly change the norm simply by making small adjustments to existing ways of doing things. If a given routine course of action is perceived to be limiting, people slowly experiment and develop their processes, which can have knock-on effects that cause bigger institutional changes [20]. Therefore, tasks interdependent with each other will be impacted by change. Making the role of managers creating and managing these institutionalized routines critical [19].

Changing of institutions can often occur at the hands of less powerful members within an environment, as they are the ones carrying out the day-to-day processes that are more subject to subtle change, creating a slowly evolving wider institutional shift [21]. These lower-level players often have the most to gain from change but have a lack of influence and resources to achieve change. Conversely, higher level actors may have the means and resources but lack the motivation to initiate change.

Through incorporating agency, neo-institutional theory has combined the logic of the resource-based view, which will allow managers to adapt to institutional pressures, which in turn will develop a competitive advantage [22]. Neo-institutional theory features sociological origins but anchors its arguments on the basis that organizations are socially afforded legitimacy due to the firm’s acceptance of several institutional pressures such as coercion and mimetic pressures [22].

Although institutional forces can influence an organization’s behaviour, actors can in turn also influence the institution. Those who take on this role are referred to as institutional entrepreneurs [17]. They can consist of a single organization or a group within an environment. These entrepreneurs act as change agents, aiming to break the status quo by transforming existing institutions or by potentially creating new ones. These agents may act in such a way intentionally or unintentionally. If entrepreneurs initiate and actively participate in driving institutional change, they can be considered institutional entrepreneurs [23].

Institutional change comes in many shapes, sizes and forms. The degree of change is dependent on several factors specific to each institution, namely, the field characteristics and the actor’s social position [23]. One way in which institutional entrepreneurs can evoke change is through their experience across fields. Those who are involved in different institutional environments can learn new techniques and ways of doing things, which they can adopt and utilize across fields to promote change. This crossing of fields, sometimes referred to as ‘boundary-bridging’, is one of the key ways in which institutional change can develop [24].

Institutional change is also subject to characteristics within a field that promote entrepreneurship. Firstly, uncertainty within a field often prompts institutional change. Actors are motivated to solve problems they are facing and, thus, can begin to question and evolve their current practices [25]. Once the first actors make a change and realize success, more are likely to follow when they find themselves in similar situations. Consequently, the status quo slowly evolves to a new practice, aimed at increasing efficiency [24]. The state of a given field can also promote institutional entrepreneurship by the actors within it. Particularly, fields in a state of crisis typically find problems and inefficiencies highlighted, encouraging the actors within to adopt and accept change in a bid to reduce the crisis [26]. Change can occur in even the most mature and deeply embedded fields [27]. Both these concepts build on problems and inefficiencies driving embedded actors to behave in ways contrary to their ingrained status quo.

Neo-institutional theory introduced isomorphism and defined it as a process resulting from the inter-relations between the institutional context and the organization [22]. Therefore, organizations operating within uncertain environments such as commercial aviation tend to appear similar, often modelling processes off competitors.

Isomorphism is a constraining process that compels one body in a population to resemble others that face the same set of environment conditions [28]. That is, over time, organizations are moulded and shift to resemble each other. The isomorphism occurs due to external forces and pressures that are too great to overcome or have consequences too large if not followed [29]. Three key forces have been proposed to drive isomorphism: coercive, mimetic and normative pressures [17].

Within the context of institutional theory, isomorphism operates through several factors such as contextual values, symbols and ceremonies, along with the practices adopted by organizations [22]. These factors then lead firms to accept institutional pressures to obtain the social support of stakeholders such as adhering to regulations for economic or social justification [22].

A legitimate firm will have better access to resources and more support from society, making legitimacy itself a resource [30]. Adopting legitimate practices, which inherently contributes to an isomorphic state, increases the probability of survival for a firm [19]. Consequently, firms are often compelled down the path that has been adopted and evolved by the legitimate bodies within their environment. Failure to adopt these deeply embedded practices can make a firm an outcast.

Much of the study in this field is focused on mature organizations operating in established legal environments, leaving a blind spot around emerging sectors [31]. Thus, a key stimuli for change are new technologies. New technologies have enabled the creation of new business sectors, operating in areas untouched by legacy organizations and unregulated by government [26]. The increase in entrepreneurs can challenge the existing order established under institutional pressures [26].

Therefore, in the context outlined above, this study seeks to investigate the issues surrounding the use of drones for the delivery of pharmaceuticals to rural Australia. To understand and interpret these issues, the study will use the forces and principles of institutional theories.

2. Materials and Methods

To inductively shed light on the key issues associated with the use of drones for the delivery of pharmaceuticals in Australia, a series of interviews were conducted using convergent interviewing, an inductive qualitative research method [32]. This section will summarize the steps taken to conduct a convergent interview process.

In the convergent interviewing process, there are multiple checks built-in to ensure rigor is maintained. For example, to avoid undue influencing of the interviewee, every interview starts with the same focus question, lessening the potential for contamination from the interviewer or other interviewees. The process also engages with disconfirming evidence, using the probe questions to explain any differences in perspective found in common issues. That is, if both interviewees in a round raised an issue and agreed as to its’ effects on the current situation regarding using drones for medication delivery in Australia, the researchers generated a probe question to find exceptions to that relationship. If both interviewees in a round raised an issue but disagreed about its nature, the researchers generated a probe question to clarify the differences. Issues raised by only one interviewee were not pursued, a key difference between interviewing until saturation versus interviewing for converging, common issues [33]. The study was covered by ethics approval (Swinburne University of Technology, Human Research Ethics Committee Ref: 20226665-10564).

A steering committee consisting of experienced and knowledgeable professionals, with both academic and industry backgrounds, reviewed the final interview question and gave suggestions of contacts from the field as possible interviewees. The steering committee are only general advisors and do not participate in the interviewing process. The focus question for the interviews was “What are the regulatory issues surrounding the use of drones for the delivery of pharmaceuticals to regional and rural Australia?” The interviewee nominees were combined with suggestions from the authors. The list of potential interviewees was then reviewed using the considerations from [32]. That is, the wider group discussed and selected the person they believed was the most knowledgeable about the specific focus question. The group then determined the person who could be the next most knowledgeable about the specific question but who was as different as possible from the first person. The third interviewee was then determined by choosing the person believed to be the next most knowledgeable from the broader list but who was as different as possible from the first two prospective interviewees. This selection process continued until all of the nominees had been listed in sequence. The interviewees were analysed in rounds of two, who were interviewed using the starting question.

Convergent interviewing focuses on the content in common across interviewees within a round of the interviews rather than on the interviewees themselves. Therefore, after a round of interviews is completed, the issues raised in each interview in that round are analysed to find common issues between the respondents. Issues raised by only one respondent are discarded, while common issues are used to form probe questions. If both respondents agree about the role of the issue in forming the current regulatory environment, new questions will probe this until any exceptions are found. If respondents both raise an issue but disagree about its role, probe questions will be used to explore this difference. Probe questions generated from the results of any round were also asked in subsequent rounds of interviews, along with the focus question.

Unlike interviews that are conducted until some assessment of saturation, convergent interviewing has a built-in end point [32]. That is, the rounds of convergent interviews continue until two rounds occur with no new common issues raised, at which point the process is completed.

The issues raised from a completed set of convergent interviews are usually detailed and inter-connected and typically take five to seven rounds to complete [32]. However, in this case, the issues arising from the interviews converged after three rounds but were still relatively broad (e.g., compared to the results of [33]).

Usually, the later rounds break the broader issues down in to more detailed issues. However, possibly because of how new this field is, there were seen to be few avenues for going in to more detail about issues because there was so much uncertainty and any more detail would depend on one of the larger issues being acted upon and changing. That is, there needed to be more details in the regulations before the interviews could have continued to their usual end. Instead, the interviews finished after surfacing the larger issues and the same issues were coming up across interviews, without breaking in to more detail. In terms of the truncated convergent interviewing process that was conducted in this study, it appears that common details could not emerge because there was too much uncertainty in the field of using drones for medication delivery and the finer issues had not yet become consistent.

Note that those interviewed as part of the convergent process were experts spanning a variety of stakeholders within the field of using drones for medication delivery, which should limit any bias towards any given stakeholder. That is, all six of the interviewees for the convergent interviews were senior members of industry or government, including the regulator. The experts interviewed came from both public and private sector backgrounds and from the private and public sector in terms of their current roles. The private sector interviewees were in or near the level of the C-suite. The public sector experts were current or former heads of relevant units. There were few people who were expert across all of the fields covered by the research question, and most of them in Australia were interviewed, with any remaining experts being unavailable, or had less expertise than those interviewed and were less able to comment on both fields of regulation or the associated issues. The results arising from the convergent interviews were also validated in discussions and interviews with four field-limited experts such as aviation academics, who could not provide further details due to the uncertainty associated with this field.

3. Results

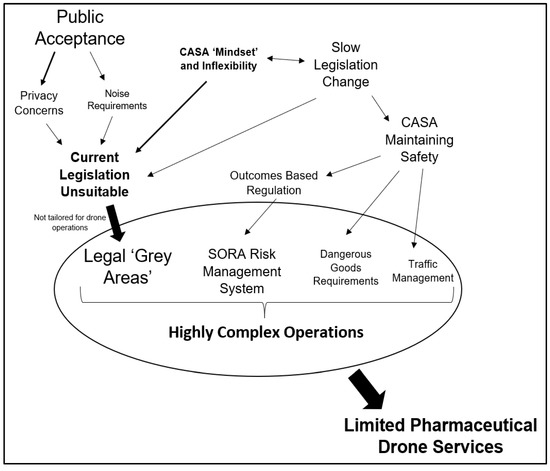

The common issues raised amongst the experts highlight the complex challenges operators face when developing drone networks for the delivery of pharmaceuticals. Legal grey areas, regulator inflexibility and other regulatory concerns stemming from strong institutional forces have created an environment that has limited the use of drone delivery networks as a means of improving the stark health gap that currently exists in rural Australia. The complex set of issues summarised in Figure 1 include many that may need to be addressed or changed in order to see a growth in the drone medication delivery network.

Figure 1.

A simplified summary of the results and their relationships.

The current regulatory environment from an air operators’ perspective has been rudimentarily adapted from traditional, general aviation regulations to unmanned aerial vehicle operation. The basic adaptation has caused significant deliberation with CASA and actors such as emerging operators or operators considering entering the industry and subsequent institutional environment should apply pressures to develop a more favourable institutional environment.

CASA’s adoption of the 1998 CASR Act has allowed for a transition from prescriptive regulation to “outcome”-based regulation, allowing operators the chance to prove that operations can be conducted safely and that the required standards are achieved through appropriate means. Although the bias towards manned aircraft operations remains, improvements and changes within CASA’s organizational structure are slowly shifting.

The transition between regulatory structures from prescriptive to outcome based has caused several undefined legislative areas. These grey areas are to be expected given the scale of the changes and has opened several avenues for innovation and subsequent increased speed of regulatory change.

An important step toward the implementation of widespread drone use is the development of a transparent set of privacy laws that provides both the public and the operator with concrete and definitive rights and responsibilities. For example, drone operators often use camera software within their landing systems as a means of ensuring the safety of the landing site. These cameras must be able to identify persons and hazards within a landing area as means of ensuring safety and mitigating risk during this critical stage of flight.

Although the use of a camera in the landing process seems logical and safety-driven, it naturally raises concerns for the public who may wonder what this captured data is being used for after the fact. Do operators maintain the right to store and use the data for the means of improving artificial intelligence technology? Could the image data be seen as an invasion of privacy? What security measures are in place to allow this technology to enhance safety while maintaining the privacy of the citizen?

These questions raise important issues currently facing the implementation of drone delivery services. That is, the regulation is currently not adequate or specific enough for drone operators and citizens alike. The rights and responsibilities of the operator are not clear and they find themselves in an awkward position of not fully understanding what they can and cannot do, creating a situation where operators are unwilling to ‘push too far’ or act in an area that is not clearly defined, unsure of their rights with potential infringements and repercussions. These ‘Legal Grey Areas’ provide challenges and ambiguity that makes it very difficult to set up an operation that abides by all laws and regulations while still being able to achieve business goals.

Dangerous goods and associated packaging materials and requirements also remained important. Discrepancies between how the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and CASA handle dangerous goods such as blood samples and prescription medication is not clearly understood. Further, cargo security measures are also poorly defined within an unmanned drone operational context. Issues surrounding environmental contamination, types of locking mechanism, delivery systems and persons able to interact with the drone and its package lack clarification.

Present regulatory conditions have hindered development through insufficient ability for coordination and collaboration between primary regulators and industry operators. Creating a collaborative environment where the regulator invites investigation through industry consultation and focused, relevant studies would further increase both the regulator and operator’s agency.

Transitioning to an outcome based regulatory structure has helped to initiate the conversation of insufficiently defined regulations; however, the onus has been placed on operators rather than the regulator. The resulting agency has increased as a result in the theoretical sense; however, with CASA still the sole regulator maintaining the authority to institute change, CASA maintains sole decision-making power. Agency refers to the ability to make change. Operators have been given the opportunity to suggest how change should be adopted; however, any suggestion must first pass-through CASA.

Evidence such as the transition to CASA’s Civil Aviation Safety Regulation (CASR) 1998 Act and adoption of the seven standard scenarios and Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) guidelines are highlighted; however, minimal resultant change to each party’s agency is achieved. Agency could be provided to operators to allow for innovation within an emerging industry, and these operators should be willing to accept and operate with an increasingly flexible regulatory environment until standard practices have been adopted and proven adequate and dependable.

With drone activity expected to continue to rise, particularly around populous areas, issues such as priority systems, levels of acceptable automation, communication and surveillance systems, and applicability of regulations between both manned and unmanned aircraft remain undefined. Unmanned drone delivery operations will primarily operate outside line of sight, providing CASA with a difficult task of ensuring safe operations without impacting operational feasibility. For now, it appears CASA’s adoption of a risk averse mentality is both keeping the industry safe and substantially inhibiting innovation and expansion of the industry. Clearly, the relevant expansion of regulations regarding landing areas and risk management strategies such as SORA can benefit from further development.

The combined effect of the above and other issues on the potential industry is an increase in operational complexity. Without clarification or refinement to the current regulatory structures operators, the industry and the public will be negatively impacted. Civilian aviation regulations appear to be the largest hindrance to sufficient innovation and regulatory improvement.

There were also sets of less critical but still influential issues in the results such as privacy and noise considerations. Privacy concerns, primarily focused on unmanned aircraft overflying and landing on or near private property and the operation’s effect on public confidence, were a key focus. Further, considerations of air rights and cameras or sensors used for aircraft operations inclusive of the associated captured data were also of significant interest.

In conjunction with privacy concerns, the results suggest important concerns regarding noise pollution within a drone’s area of operation and the impacts on both the public and socially sensitive areas. Associated operational considerations include whether to operate at day or night, at a low level, in built up or sparsely populated areas, and associated impacts on landing areas.

4. Discussion

When compared with urban areas, those living in regional and rural Australia find themselves at a significant disadvantage in terms of healthcare access. Consequently, rural Australians have a life expectancy that is dramatically lower and even basic health supplies can become sparse. These challenges require a new method to achieve a consistent supply of pharmaceuticals. This study aims to understand the issues and regulatory factors that have limited the use of drones for delivery of pharmaceuticals to rural and regional Australians, through the framework of institutional theory.

Among the issues raised were concerns about regulator flexibility. The results indicated that the aviation regulator (CASA) has become somewhat embedded in its practices. The lack of flexibility has led to some drone regulations being developed with a similarity to conventional aviation regulations, creating a situation where regulations are not appropriately designed for drone operations, making it unnecessarily difficult for drone operators to understand their rights and responsibilities, hindering the expansion of drone delivery networks. Notably, the pharmaceutical regulations were not seen as overly inhibiting the advancement of this nascent industry.

The relative inability of CASA to adapt to the changing institutional situation is a telling sign of their position in the environment. The lack of flexibility displayed by CASA is symptomatic of their high level of embeddedness, stemming from their need to maintain legitimacy through their use of legitimized practices. These practices are seen to be sub-optimal and actively constraining the advancement of Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems oriented industries in Australia. However, all organizations are dependent on legitimacy and will maintain legitimized practices, even if they are not the most optimal for the current environment [34]. Therefore, a mature organization such as CASA can be expected to prioritize maintaining their current level of legitimacy ahead of innovative practices that risk it.

CASA is a safety authority and can be expected to take a conservative approach and to prioritize operational safety ahead of service advancement. The resulting regulatory system tried to incrementally move, but the efficacy of their ruleset is ultimately compromised by CASA’s attempts to secure their own legitimacy (as predicted by [31]).

For change to occur at an institutional level within CASA, there would need to be internal pressure within the organization to drive such change. However, the embedded agency paradox limits the ability of actors within an embedded organization to provoke change. Actors within CASA are embedded within the organization themselves and subject to the same institutional pressures (per [25]). Peripheral actors such as industry partners or consultants can see the need for change within CASA, but the distribution of agency within the field and industry limits their ability to initiate change [35].

Obtaining the array of approvals required to set up an operation that can utilize drones for the delivery of pharmaceuticals is already a difficult process given the strict nature of CASA and other regulatory bodies. A misstep in relation to the laws can have harsh outcomes on existing approvals and severely limit business models. Consequently, operators feel the pressure to tread carefully in all aspects of their work, and approaching an unexplored and under-developed area such as drone privacy exposes organizations to an additional risk they may not be able to justify. Coercive pressures gain their strength when one party is dependent on another [17]. In this case, prospective operators are heavily dependent on approvals from CASA and other regulatory bodies. Without the support of the regulator, businesses lose legitimacy in the sector and may be doomed to failure [29]. Providing clear, concise laws in relation to privacy will help to alleviate some pressure and encourage more operators within the sector.

In a similar manner to privacy laws, regulation surrounding drones and their noise pollution are under-developed and ambiguous. There is currently no international standard for what drone noise law should look like. Operators need to have this area of regulation clearly defined because it directly influences drone design, flight paths and traffic density. These laws need to differ from those concerning the wider aviation industry. A drone is a completely different vehicle in comparison to a classic aircraft, both in terms of drones having reduced size and noise output, and closer proximity to built-up areas.

Further, drone operators must also be careful of the sensitive areas over which they may be flying. Schools, hospitals and indigenous sites present some of the highly sensitive areas that may be present in the areas in which these drones operate. Being respectful and defining clear boundaries will help to develop public trust and acceptance. Such public acceptance could help in developing the legitimacy of the service. When the wider community can understand and feel comfortable with drones and their purpose, the organizations utilizing them for good gain power within the industry and the public [19]. Building legitimacy provides the framework for continued innovation and agency.

Firms must work hard not only to obtain their legitimacy but also to retain it over time [30]. As an evolving and adapting industry, maintaining legitimacy is crucial for continued agency and entrepreneurship. Without legitimacy, firms stand little to no chance of creating institutional change.

Elements of isomorphism were evident through our results with competing firms attempting to understand and comply with regulatory requirements while attempting to maintain a competitive advantage. However, these situations often lead to competitors modelling operations off one another [22].

Normative pressures were presented within our results through CASA’s requirements to submit operational expositions detailing operations for approval, requiring operators to conform and comply with outlined requirements [19]. Even though CASA invites varying methods, its predetermined requirements generate normative pressures often inhibiting operational performance [17].

Mimetic pressures were prominent, with CASA often adopting Federal Aviation Administration of the United States of America (FAA) decisions [22]. The FAA is the largest and most internationally trusted civilian aviation regulator, meaning CASA’s adoption of the FAA’s technical and regulatory decisions could place a spotlight on CASAs underdeveloped and poorly defined objectives (applying [17]). Without first developing sound, substantiated regulatory objectives, CASA will struggle to encourage involvement within the industry due to a perceived lack of confidence.

Coercive pressures are clearly displayed between CASA and operators, with operators pressured to behave or operate in a specific manner that complies with CASA’s predetermined regulatory objectives. Coercive pressures can be beneficial, such as by providing approvals; however, should an operator deviate from CASAs planned trajectory, any benefits could be lost, resulting in reputational or economical loss [29].

Creating Institutional Change, Agency and Institutional Entrepreneurship

Although their embeddedness has severely limited CASA’s ability to change, the regulator has managed some progress towards reforming the institutional environment. The introduction of outcome-based legislation—most notably, the SORA risk management system—represents CASA’s attempts to innovate. Although innovation risks organizational legitimacy in the short term, innovation provides a basis for legitimacy to be built on in the long term if it proves to be successful [19]. Successful innovation to modernize the regulatory environment will secure CASA’s position in a rapidly changing institutional environment.

CASA has become too embedded, resulting in insufficient agency to initiate change and without which the drone industry will remain insufficiently regulated. Agency requires market power to initiate change; therefore, operators who typically are emerging businesses lack legitimized influence and, thus, agency. Consequently, a paradox becomes evident, one that must be addressed for the development of the drone industry. One way forward could be for emerging operators to combine efforts to further increase agency and to motivate the regulator to initiate change within the present regulatory structure [17].

Further, streamlining drone regulation could also benefit logistics companies facing the ‘last mile’ problem, at least initially in rural areas, while reducing carbon emissions (e.g., per [6]). The sustainability advantages of drones over other delivery means will increase further as more of the electricity produced in Australia comes from renewable sources (applying [7]). In general, whether for medication delivery or e-commerce, the use of drones needs a system-wide approach to transport sustainability [8] and the results from this study may help to inform the next changes enabling drone delivery in Australia.

This study was not without its limitations. In particular, only six very high-level experts were interviewed across three rounds of interviews, with four other experts such as aviation academics being interviewed afterward to validate the results in a confirmatory manner due to their narrower fields of expertise. Although the experts interviewed in the convergent interviews provided invaluable insight into the regulatory issues facing pharmaceutical drone delivery in Australia, convergent interviewing becomes more detailed with a greater number of rounds and in situations that have stabilized. More rounds and interviews could have provided even more insight into common issues, as well as further advancement of probe questions to provide a deeper understanding of the challenges facing the industry. Future research would benefit from a wider pool of deep experts. Alternatively, because this topic covered two fields of regulation and is still a very nascent area, it may be difficult to find the large array of experts with the required depth of expertise, suggesting a potential boundary to the use of convergent interviewing, where diagnostic tools transition to forecasting tools.

Another limitation of this study is its scope and interviewees being limited to Australia. Further research could explore issues faced internationally in developing drone networks for similar purposes. That research could help to better understand global standards and challenges, as well as provide insight into ways overseas regulators have developed and implemented drone regulations.

5. Conclusions

Until drone regulations are changed, the potential of this innovative and developing sector is substantially restrained and those living in regional and rural areas will continue to have limited access to basic healthcare, an unimaginable reality in a well-developed and prosperous country such as Australia. A lack of adequate regulation tailored towards drone delivery operations in Australia has limited the industry and its potential to provide a positive impact on people’s lives. The country finds itself in a position where regulatory inflexibility is costing the lives of those living in rural and regional areas. Access to basic healthcare should be a given for all Australians, regardless of location.

Many Australians currently find themselves travelling hundreds of kilometres to obtain necessary pharmaceuticals. Drones provide a means by which pharmaceuticals can be remotely delivered to these hard-to-access areas in a timely fashion, which would save lives and improve the way of life for hundreds of thousands of Australians. The bodies regulating these fields need to continue to act, particularly in terms of streamlining regulations that currently hinder drone operators in regional and rural Australia.

Some specific areas that could benefit from improvement in regulation are with regard to privacy and noise regulation. Efforts to develop appropriate regulation in the areas of privacy and noise could be used as starting points for regulatory change in the field of using drones for medication delivery. Engaging the issues raised in the results of this study could help advance the growth of the drone industry and improve public health issues, with the resulting potential of creating positive change for those currently without adequate healthcare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.H., M.H., A.B. and J.R.; methodology, W.H., M.H., A.B. and J.R.; investigation, W.H., M.H. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, W.H., M.H. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, W.H., M.H., A.B. and J.R.; supervision, J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Swinburne University of Technology (Human Research Ethics Committee Ref: 20226665-10564, final approval 16 August 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the participation of all of the interviewees and the support from D.M.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AIHW. Rural and Regional Health, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2019. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-remote-health/contents/access-to-health-care (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Tan, A.C.W.; Emmerton, L.; Hattingh, L. A review of the medication pathway in rural Queensland, Australia. Int. J. Pharm. Pr. 2012, 20, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisingizwe, M.P.; Ndishimye, P.; Swaibu, K.; Nshimiyimana, L.; Karame, P.; Dushimiyimana, V.; Musabyimana, J.P.; Musanabaganwa, C.; Nsanzimana, S.; Law, M.R. Effect of unmanned aerial vehicle (drone) delivery on blood product delivery time and wastage in Rwanda: A retrospective, cross-sectional study and time series analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e564–e569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoblauch, A.M.; de la Rosa, S.; Sherman, J.; Blauvelt, C.; Matemba, C.; Maxim, L.; Defawe, O.D.; Gueye, A.; Robertson, J.; McKinney, J.; et al. 2019 Bi-directional drones to strengthen healthcare provision: Experiences and lessons from Madagascar, Malawi and Senegal. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, C. Medical Deliveries by Drone Ready for Take-Off in Australia, The Sydney Morning Herald. 2021. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/business/small-business/medical-deliveries-by-drone-ready-for-take-off-in-australia-20210219-p573z8.html (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- Benarbia, T.; Kyamakya, K. A Literature Review of Drone-Based Package Delivery Logistics Systems and Their Implementation Feasibility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, S.; Suh, K. A Comparative Analysis of the Environmental Benefits of Drone-Based Delivery Services in Urban and Rural Areas. Sustainability 2018, 10, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patella, S.; Grazieschi, G.; Gatta, V.; Marcucci, E.; Carrese, S. The Adoption of Green Vehicles in Last Mile Logistics: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Pharmacy Guild of Australia. COVID-19—Home Delivery of Medicines, The Pharmacy Guild of Australia. 2020. Available online: https://www.guild.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0026/90971/COVID-19-Home-Delivery-Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Health, S.A. Pharmacist Legal Obligations when Handling, Dispensing and Supplying Drugs of Dependence, Government of South Australia. 2022. Available online: https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/clinical+resources/clinical+programs+and+practice+guidelines/medicines+and+drugs/legal+control+over+medicines/legal+requirements+for+the+prescription+and+sup-ply+of+drugs+of+dependence/pharmacist+legal+obligations+when+handling+dispensing+and+supplying+drugs+of+dependence#:~:text=Sale%20or%20supply%20of%20pseudoephedrine&text=Pharmacists%20must%20not%20sell%20or,his%20or%20her%20birth%20certificate (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- CASA. Remotely Piloted Aircraft Operator’s Certificate, Civil Aviation Safety Authority. 2022. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/drones/get-your-operator-credentials/remotely-piloted-aircraft-operators-certificate (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- CASA. Apply for beyond Visual Line-of-Sight Approvals, Civil Aviation Safety Authority. 2022. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/drones/registration-and-flight-authorisations/apply-flight-authorisations/apply-beyond-visual-line-sight-approvals (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Swoop Aero. Swoop Aero Obtains ‘Beyond Visual Line of Sight’ Approval in Australia, Swoop Aero. 2021. Available online: https://swoop.aero/media-releases/swoop-aero-obtains-bvlos-approval-in-australia (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Brightmore, D.; Airobotics Receives First CASA Approval for BVLOS Drone Flights in Australia from Remote Ops Centre. Mining Digital. 2020. Available online: https://miningdigital.com/technology/airobotics-receives-first-casa-approval-bvlos-drone-flights-australia-remote-ops-centre (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Swoop Aero. An Aussie First: Swoop Aero Is Coming to the USA for Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) with their Newly Unveiled Aircraft Kite. 2021. Available online: https://swoop.aero/media-releases/newly-unveiled-aircraft (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Swoop Aero. Swoop Aero Obtains CASA Approval for Remote Operations Centre, Swoop Aero. 2022. Available online: https://swoop.aero/media-releases/swoop-aero-obtains-casa-approval-for-roc (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable competitive advantage: Combining institutional and resource-based views. Strat. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, L.G. Institutional theories of organization. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 1987, 13, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Oliver, C.; Lawrence, T.B.; Meyer, R.E. The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Grenville, J.; Golden-Biddle, K.; Irwin, J.; Mao, J. Liminality as Cultural Process for Cultural Change. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 522–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alles, M.D.L.L.; Valle-Cabrera, R. Reconciling institutional theory with organizational theories how neonationalism resolves five paradoxes. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2006, 19, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Leca, B.; Boxenabum, E. How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 65–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Suddaby, R. Institutional Entrepreneurship In Mature Fields: The Big Five Accounting Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.G.; Creed, D. Institutional contradictions, praxis, and institutional change: A dialectical perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, S.; Hardy, C.; Lawrence, T.B. Institutional entrepreneurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy in Canada. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fligstein, N.; Mara-Drita, I. How to Make a Market: Reflections on the Attempt to Create a Single Market in the European Union. Am. J. Sociol. 1996, 102, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, A.H. Ecology and Human Ecology. Soc. Forces 1944, 22, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaja, S.A.; Gabriel, J.M.O.; Wobodo, C.C. Organizational isomorphism: The quest for survival. Noble Internat. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2019, 3, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Gibbs, B.W. The Double-Edge of Organizational Legitimation. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolka, K.M.; Heugens, P.P.M.A.R. The Emergence of Proto-Institutions in the New Normal Business Landscape: Dialectic Institutional Work and the Dutch Drone Industry. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 626–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, B. Convergent Interviewing, 3rd ed.; Interchange: Chapel Hill, QLD, Canada, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Thynne, L.; Rodwell, J. A Pragmatic Approach to Designing Changes Using Convergent Interviews: Occupational Violence Against Paramedics as an Illustration. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2017, 77, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Agency- and institutional-theory explanations: The case of retail sales compensation. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 488–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Karnøe, P. Bricolage versus breakthrough: Distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).