Understanding Incubated Startups’ Continuance Intention towards Entrepreneurial Incubation Platforms: Empirical Evidence from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Existing Research in Entrepreneurial Incubation Platforms

2.2. The Dual Model Framework

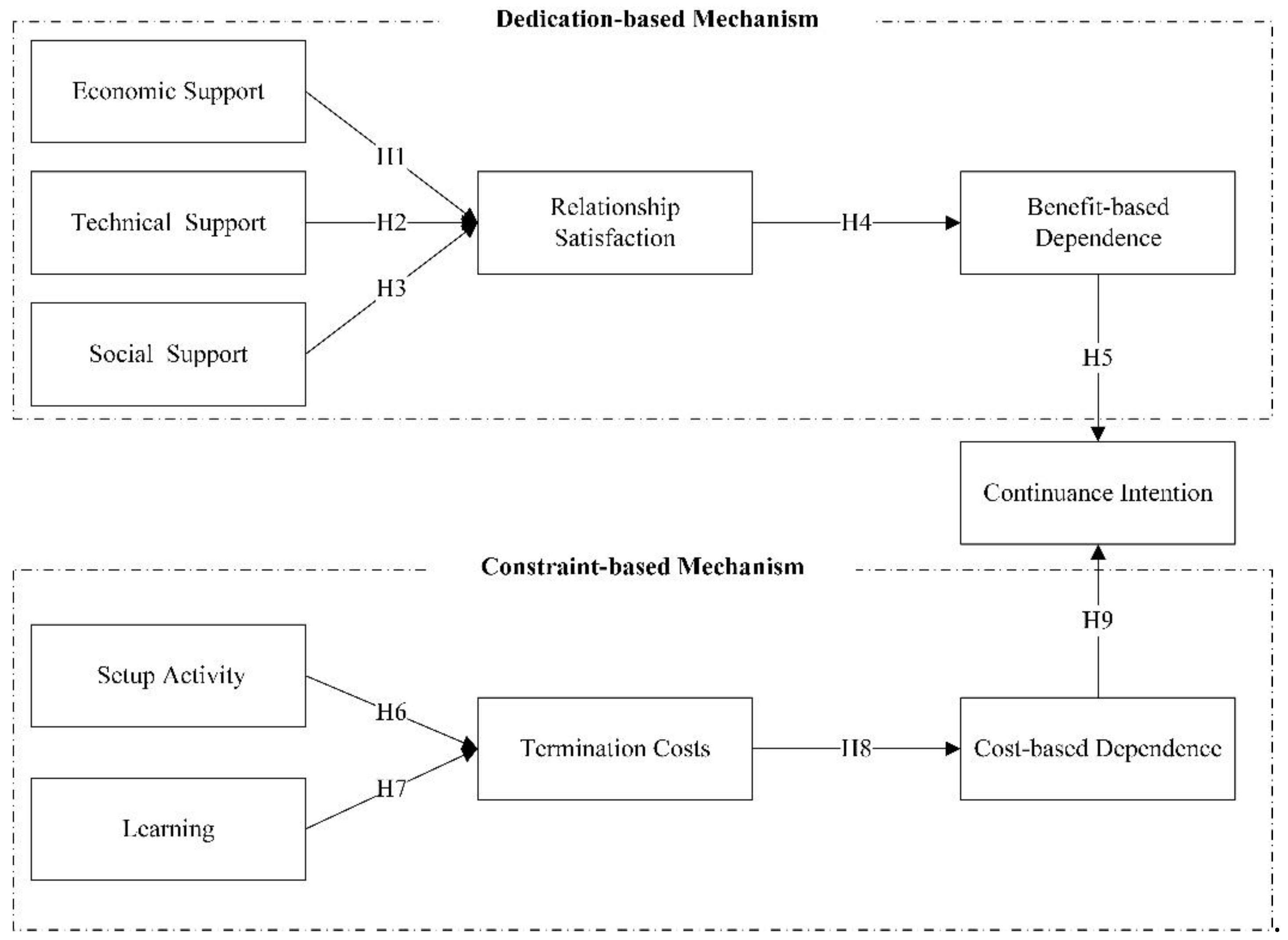

3. Research Model and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Dedication-Based Mechanism

3.1.1. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Support on Relationship Satisfaction

3.1.2. The Effect of Relationship Satisfaction on Benefit-Based Dependence

3.1.3. The Effect of Benefit-Based Dependence on Incubated Startups’ Continuous Intention towards Entrepreneurial Incubation Platforms

3.2. Constraint-Based Mechanism

3.2.1. The Effect of Relationship-Specific Investment on Termination Costs

3.2.2. The Effect of Termination Costs on Cost-Cased Dependence

3.2.3. The Effect of Cost-Based Dependence on Incubated Startups’ Continuance Intention towards Entrepreneurial Incubation Platforms

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample

4.2. Measurements

4.3. Common Method Variance (CMV)

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model

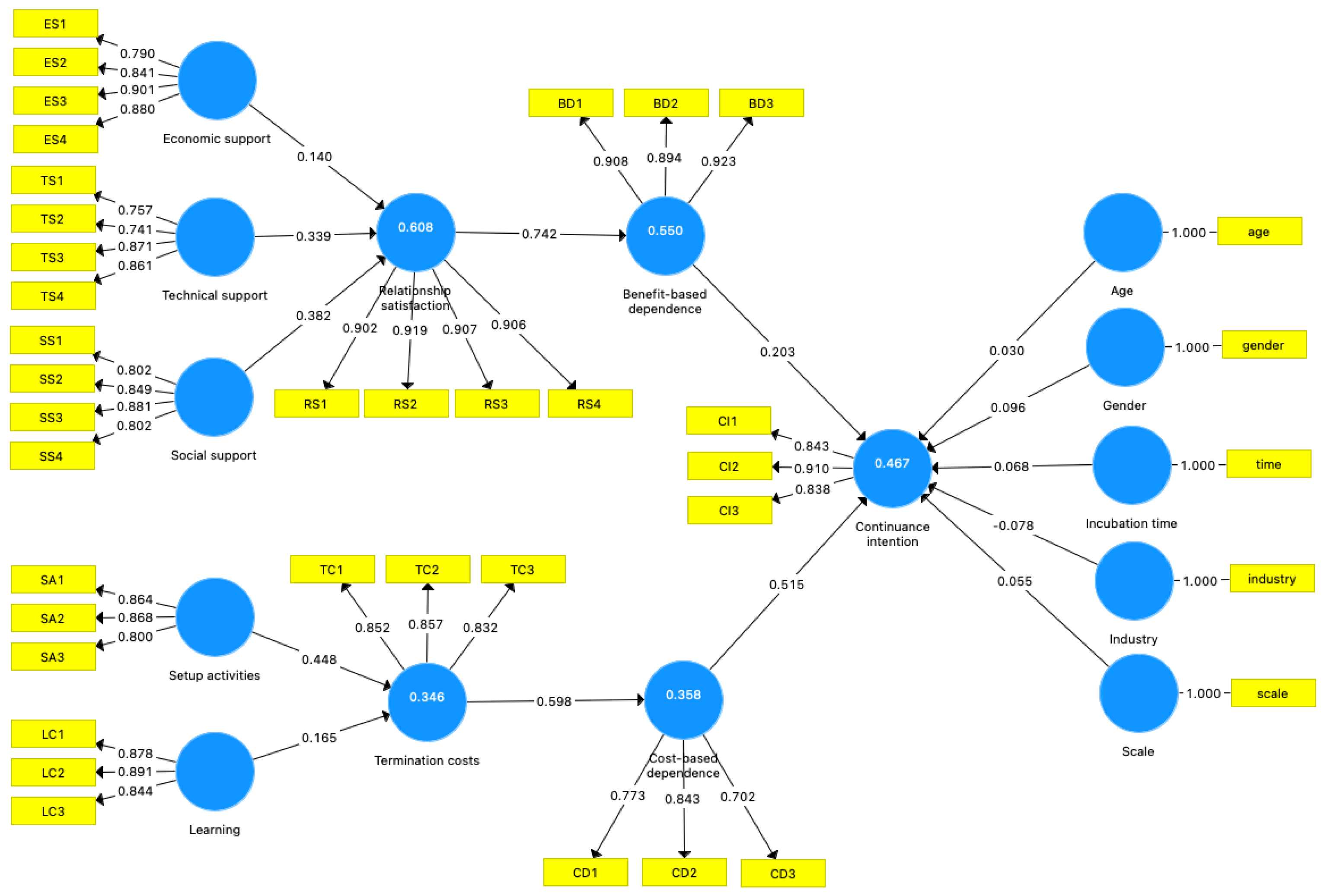

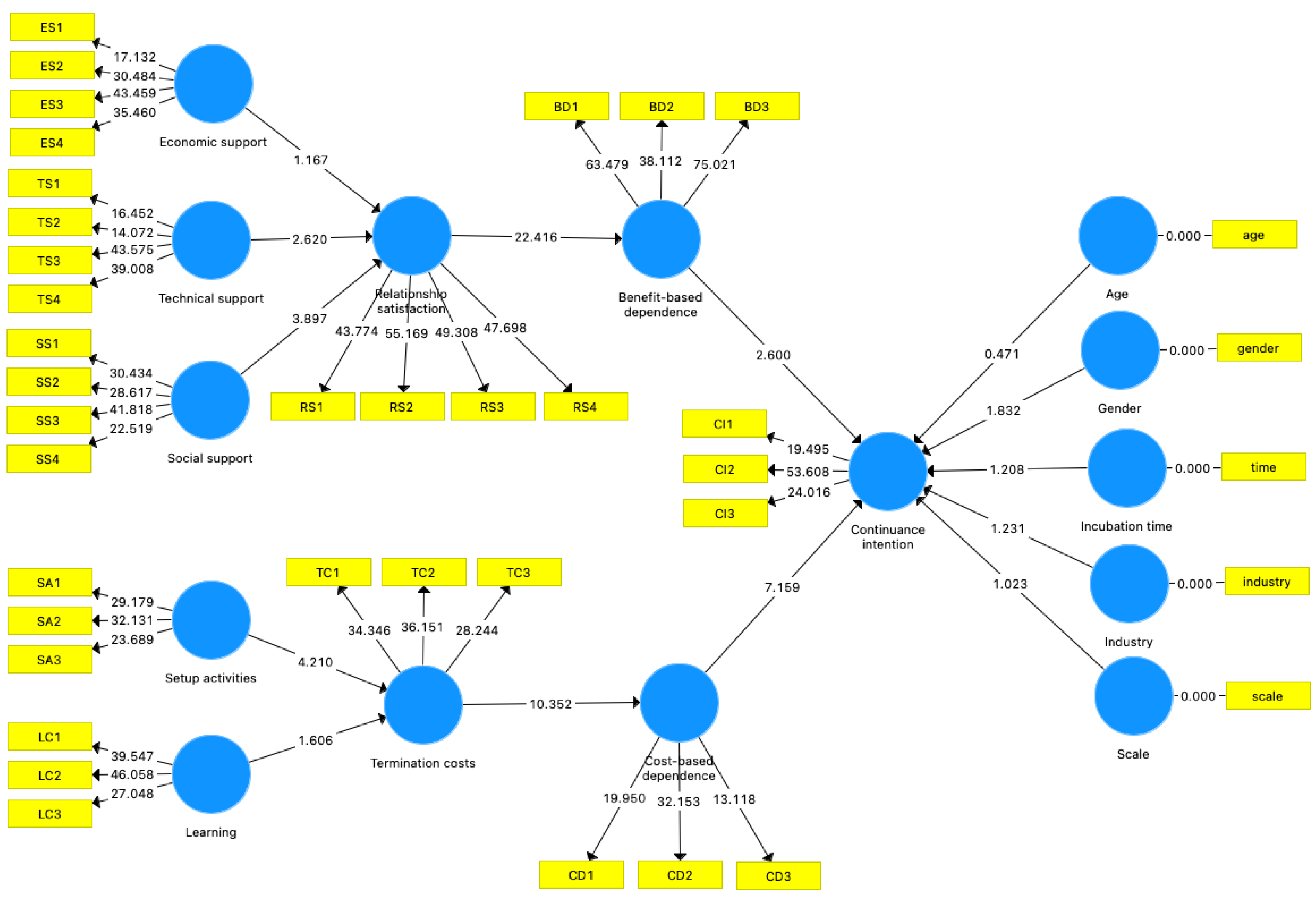

5.2. Structural Model

6. Discussion

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Items | Wording | References |

| Economic support | ES1 | I am able to save costs on space by using the entrepreneurial incubation platform | Han [7]; Wu [25] |

| ES2 | I am able to save costs for office appliances and equipment by using the entrepreneurial incubation platform | ||

| ES3 | I am able to save costs for entrepreneurial services by using the entrepreneurial incubation platform | ||

| ES4 | I am able to save costs on entrepreneurial training programs by using the entrepreneurial incubation platform | ||

| Technical support | TS1 | The entrepreneurial incubation platform offers sufficient spaces for my entrepreneurial activity | |

| TS2 | The entrepreneurial incubation platform provides various office appliances and equipment for my entrepreneurial activity | ||

| TS3 | The entrepreneurial incubation platform provides sufficient and high-quality technical services for my entrepreneurial activity | ||

| TS4 | The entrepreneurial incubation platform offers various entrepreneurial training programs and on-the-spot support. | ||

| Social support | SS1 | The entrepreneurial incubation platform supports the collaboration among peers | |

| SS2 | The entrepreneurial incubation platform provides aids to share knowledge and skills among peers | ||

| SS3 | The entrepreneurial incubation platform supports the communication among peers | ||

| SS4 | The entrepreneurial incubation platform provides chances to meet entrepreneurial experts and mentors | ||

| Relationship satisfaction | RS1 | It is a pleasure working with the platform owner | Benton [59] |

| RS2 | The platform owner is a good partner to do business with | ||

| RS3 | We are satisfied with the daily relationship with this platform owner | ||

| RS4 | The exchange relationship with this platform owner is satisfactory | ||

| Benefit-based dependence | BD1 | It would be very difficult to replace the benefit generated by this entrepreneurial incubation platform | Scheer [39] |

| BD2 | If we had not settled in this incubation platform, our company’s development would not be so good | ||

| BD3 | Our company obtains benefit from the relationship with this platform that cannot be offered by other alternative platforms | ||

| Setup activities | SA1 | It took much time for me (us) to go through all the required steps before settling in this platform | Burnham [60]; Heide [38] |

| SA2 | There were many formalities involved for me (us) to initiate the exchange relationship with the platform owner | ||

| SA3 | I (we) have made significant investments for the purpose of settling in this platform | ||

| Learning | LC1 | Learning for the management rules issued by this platform took much time and effort | Kim [35] |

| LC2 | I (we) spent a lot of time and effort in learning how to operate a startup in accordance with the requirements of this platform | ||

| LC3 | There was a lot involved for me (us) to clearly understand how to successfully cooperate with this platform | ||

| Termination costs | TC1 | The potential losses that would result from terminating the exchange relationship with the platform owner are trivial (R) | Kim [17] |

| TC2 | If I (we) no longer stay in this platform, the time and effort invested thus far will be wasted | ||

| TC3 | If I (we) end the exchange relationship with this platform owner, the time and effort I (we) already spent would be much more meaningless than if I (we) continue the exchange relationship | ||

| TC4 | It would be difficult for me (us) to replace this platform partner | ||

| Cost-based dependence | CD1 | Before I reach the graduation conditions of this platform, I will stay in this platform | Scheer [39] |

| CD2 | For our company, to locate and establish relationships with an alternative platform that replaces the current one would be a great cost | ||

| CD3 | For our company, to end the relationship with this platform would be very costly | ||

| Continuance intention | CI1 | I intend to stay in this platform until my company reaches the graduation conditions | Bhattacherjee [61] |

| CI2 | I will remain in this platform during the incubation period, and will not lift the incubation relationship with this platform in advance | ||

| CI3 | I will remain in the incubation platform during the incubation period, and will not consider other alternative platforms |

References

- Lukeš, M.; Longo, M.C.; Zouhar, J. Do business incubators really enhance entrepreneurial growth? Evidence from a large sample of innovative Italian start-ups. Technovation 2019, 82, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, Q.; Xia, S.; Sarpong, D.; Maas, G. Capacities of business incubator and regional innovation performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 158, 120125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.; Aaboen, L. The network mediation of an incubator: How does it enable or constrain the development of incubator firms’ business networks? Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 80, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.Z.; Xiang, G.P.; Wang, J.X. Research on competitiveness evaluation model of maker space from the perspective of platform. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2019, 36, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Chen, M.; Zhu, Y.H.; Song, G. Technology business incubators and regional economic convergence in China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 29, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, T.; Kingsley, J.; Price, M.; Dowling, F.; Marshall, J.; Trotter, J.; Calow, A. Made in China: Makerspaces and the Search for Mass Innovation. Nesta, 2016. Available online: https://www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/made_in_China-_makerspaces_report.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2016).

- Han, S.Y.; Yoo, J.; Zo, H. Understanding makerspace continuance: A self-determination perspective. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; Chen, Y.H.; Li, Y.L. User’s continuance usage intention mechanism in maker space: A framework based on self-determination theory. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2020, 40, 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.J.; Su, J.Q.; Lyu, Y.B.; Liu, Q. How do business incubators govern incubation relationships with different new ventures? Technovation 2022, 116, 102486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.W.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.M.; Hua, R.H.; Sun, J. A comparison of the service model between private and state-owned enterprise incubators. Sci. Res. Manag. 2018, 39, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Aerts, K.; Matthyssens, P.; Vandenbempt, K. Critical role and screening practices of European business incubators. Technovation 2007, 27, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liao, H. A dempster-shafer-theory-based entry screening mechanism for small and medium-sized enterprises under uncertainty. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 180, 121719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.L.; Lin, C.; Yong, K.; Li, Z.J.; Khan, Z. Business incubators as international knowledge intermediaries: Exploring their role in the internationalization of start-ups from an emerging market. J. Int. Manag. 2021, 27, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkov, I.; Hellstrm, M.; Wikstrm, K. Identifying the role of business accelerators in the developing business ecosystem the life science sector. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 1459–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, H.Q. Incubator control and incubateer creativity: The mediating role of resources and capabilities. Manag. Rev. 2019, 31, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwana, A.; Konsynski, B.; Bush, A.A. Platform evolution: Coevoluation of platform architecture, governance, and environmental dynamics. Inf. Syst. Res. 2010, 21, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, I.; Lee, H. Third-party mobile app developers’ continued participation in platform-centric ecosystems: An empirical investigation of two different mechanisms. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Xu, J.P.; Li, G. Do switching costs hurt new product development performance? The role of relationship quality and customer involvement. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 2552–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Liu, X.X.; Xiao, Z. A Dedication-constraint model of consumer switching behavior in mobile payment applications. Inf. Manag. 2022, 59, 103640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, S.; Wadid, L.; Alain, F. Technology business incubation: An overview of the state of knowledge. Technovation 2016, 50, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderstraeten, J.; van Witteloostuijn, A.; Matthyssens, P. Organizational sponsorship and service co-development: A contingency view on service codevelopment directiveness of business incubators. Technovation 2020, 98, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’Chirgui, Z.; Lamine, W.; Mian, S.; Fayolle, A. University technology commercialization through new venture projects: An assessment of the French regional incubator program. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 1142–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, J.L.; Macgregor, N. The influence of incubator and accelerator participation on Nanotechnology venture success. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2022, 46, 1717–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, M.; Camarero, C.; Sijde, P. Exchange of knowledge in protected environments. The case of university business incubators. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 838–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.J. Internal and external networks, and incubatees’ performance in dynamic environments: Entrepreneurial learning’s mediating effect. J. Technol. Transf. 2021, 46, 1707–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shih, T. Collective and individual social capital and the impact on incubator tenants’ graduation. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, C.; Barkema, H. Planned luck: How incubators can facilitate serendipity for nascent entrepreneurs through fostering network embeddedness. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2022, 46, 884–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, I.H.; Chou, S.W. Understanding the formation of e-loyalty based on a dedication-constraint perspective. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2017, 27, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millette, S.; Hull, C.E.; Williams, E. Business Incubators as effective tools for driving circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 121999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoraki, C.; Messeghem, K.; Audretsch, D. The effectiveness of incubators’ co-opetition strategy in the entrepreneurial ecosystem: Empirical evidence from France. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 1781–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascigil, S.; Magner, N. Trust as a determinant of entrepreneurs’ preference to remain tenants in Turkish business incubators. Psychol. Rep. 2011, 109, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givertz, M.; Woszidlo, A.; Segrin, C. Direct and indirect effects of attachment orientation on relationship quality and loneliness in married couples. J. Fam. Stud. 2019, 25, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.; Collibee, C.; Rizzo, C. Associations between dating aggression involvement and subsequent relationship commitment. J. Fam. Violence 2021, 36, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, B. An integrative view of emotion and the dedication-constraint model in the case of coffee chain retailers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.S.; Son, J.Y. Out of dedication or constraint? A dual model of post adoption phenomena and its empirical test in the context of online services. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 40–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friman, M.; Grling, T.; Millet, B. An analysis of international business-to-business relationships based on the commitment-trust theory. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2002, 31, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulles, N.J.; Ellegaard, C.; Veldman, J. The interplay between supplier-specific investments and supplier dependence: Do two pluses make a minus? J. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, J.B.; John, G. The role of dependence balancing in safeguarding transaction-specific assets in conventional channels. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, L.K.; Miao, C.F.; Garrett, J. The effects of supplier capabilities on industrial customers’ loyalty: The role of dependence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquezcasielles, R.; Iglesias, V.; Varelaneira, C. Manufacturer-distributor relationships: Role of relationship-specific investment and dependence types. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2017, 32, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Narus, J.A. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.H.; Chang, J.J.; Tang, K.Y. Exploring the influential factors in continuance usage of mobile social apps: Satisfaction, habit, and customer value perspectives. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 33, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, T.; Stockmann, C.; Kensbock, J.M. Fear of failure as a mediator of the relationship between obstacles and nascent entrepreneurial activity-An experimental approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls-Nixon, C.L.; Singh, R.; Chavoushi, Z.H.; Valliere, D. How university business incubation supports entrepreneurs in technology-based and creative industries: A comparative study. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Li, C.; Qalati, S.A.; Rehman, H.U.; Khan, A.; Rana, F. Impact of business incubators on sustainable entrepreneurship growth with mediation effect. Entrep. Res. J. 2022, 23, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, M.; Camarero, C. Social capital in university business incubators, dimensions, antecedents and outcomes. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 599–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Honig, B. The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 18, 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, L. Interactivity, engagement, and technology dependence: Understanding users’ technology utilisation behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2017, 36, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonlertvanich, K. Service quality, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty, the moderating role of main-bank and wealth status. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 278–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Kim, H.Y. Is social media marketing worth it for luxury brands? The dual impact of brand page satisfaction and brand love on word-of-mouth and attitudinal loyalty intentions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, P.; Jayachandran, S.; Rose, R.L. The role of relational embeddedness in retail buyers’ selection of new products. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, D.I.; Bello, D.C. Two sides to attitudinal commitment: The effect of calculative and loyalty commitment on enforcement mechanisms in distribution channels. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.T. Dependence and resource commitment as antecedents of supply chain integration. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2022, 28, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, H.; Miyaoka, A.; Sato, M. Relationship-specific investment as a barrier to entry. J. Econ. 2016, 119, 17–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huo, B.; Flynn, B.B.; Zhao, X. Supply chain power configurations and their relationship with performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 53, 88–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, I.; Durand, A.; Saab, S.; Kleinaltenkamp, M.; Baxtere, R.; Lee, Y. The bonding effects of relationship value and switching costs in industrial buyer-seller relationships: An investigation into role differences. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmitz, T.; Schweiger, B.; Daft, J. The emergence of dependence and lock-in effects in buyer-supplier relationships-a buyer perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 55, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Shabbir, M.S.; Salman, R.; Haider, S.H.; Ahmad, I. Do entrepreneurial orientation and size of enterprise influence the performance of micro and small enterprises? A study on mediating role of innovation. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, W.C.; Maloni, M. The influence of power driven buyer/seller relationships on supply chain satisfaction. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, T.A.; Frels, J.K.; Mahajan, V. Consumer switching costs: A typology, antecedents, and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, S.M.; Ahmed, F.; Johny, J.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A. Impact of knowledge capabilities on organizational performance in the private sector in Oman: An SEM approach using path analysis. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 17, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Asif, M.U.; Allam, Z.; Sheikh, U.A. A mediated moderated analysis of psychological safety and employee empowerment between sustainable leadership and sustainable performance of SMEs. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Sustainable Islamic Business and Finance, Sakheer, Bahrain, 5–6 December 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Klein, P.G.; Kor, Y.Y.; Mahoney, J.T. Entrepreneurship, subjectivism, and the resource-based view: Towards a new synthesis. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2008, 2, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weele, M.A.; van Rijnsoever, F.J.; Nauta, F. You can’t always get what you want: How entrepreneur’s perceived resource needs affect the incubator’s assertiveness. Technovation 2017, 59, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Rijnsoever, F.; Eveleens, C.P.; Linton, J. Money don’t matter? How incubation experience affects start-up entrepreneurs’ resource valuation. Technovation 2021, 106, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.S.; Lyv, W.F. Understanding the impact of quality elements on MOOCs continuance intention. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 10949–10976. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.L.; Zhang, W.K.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.A.; Na, S.Y. A study of Chinese consumers’ consistent use of mobile food ordering apps. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, R.F.J. Intermediaries for the greater good: How entrepreneurial support organizations can embed constrained sustainable development startups in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104438. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Heng, C.S.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Lin, Z.J. The distinct signaling effects of R&D subsidy and non-R&D subsidy on IPO performance of IT entrepreneurial firms in China. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Min, J. The distinct roles of dedication-based and constraint-based mechanisms in social networking sites. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, L. What prevent you from stepping into the entrepreneurship? Evidence from Chinese makers. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2021, 15, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qalati, S.A.; Ostic, D.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A.; Gopang, A.A.; Khan, A. Social media and SMEs’ performance in developing countries: Effects of technological-organizational-environmental factors on the adoption of social media. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221094594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Respondents (N = 534) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Gender | Male | 321 | 60.23% |

| Female | 213 | 39.77% | |

| Age | 20–30 | 354 | 66.48% |

| 31–40 | 161 | 30.21% | |

| 41+ | 19 | 3.48% | |

| Position | General manager | 391 | 73.26% |

| Vice General manager | 143 | 26.74% | |

| Educational attainment | High school or below | 57 | 10.76% |

| Associated or bachelor’s degree | 438 | 81.94% | |

| Master’s degree or high | 39 | 7.29% | |

| Enterprise scale | less than 50 employees | 456 | 85.31% |

| 50–100 employees | 48 | 9.04% | |

| 100–200 employees | 15 | 2.82% | |

| over 200 employees | 15 | 2.82% | |

| Incubation time | less than 1 year | 171 | 31.94% |

| 1–2 year | 167 | 31.25% | |

| 2–3 year | 108 | 20.14% | |

| 3–4 year | 35 | 6.60% | |

| over 4 years | 54 | 10.07% | |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading | t-Values | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic support | ES1 | 0.790 | 17.132 | 0.915 | 0.730 |

| ES2 | 0.841 | 30.484 | |||

| ES3 | 0.901 | 43.459 | |||

| ES4 | 0.880 | 35.460 | |||

| Technical support | TS1 | 0.757 | 16.452 | 0.883 | 0.655 |

| TS2 | 0.741 | 14.072 | |||

| TS3 | 0.871 | 43.575 | |||

| TS4 | 0.861 | 39.008 | |||

| Social support | SS1 | 0.802 | 30.434 | 0.901 | 0.696 |

| SS2 | 0.849 | 28.617 | |||

| SS3 | 0.881 | 41.818 | |||

| SS4 | 0.802 | 22.519 | |||

| Relationship satisfaction | RS1 | 0.902 | 43.774 | 0.950 | 0.826 |

| RS2 | 0.919 | 55.169 | |||

| RS3 | 0.907 | 49.308 | |||

| RS4 | 0.906 | 47.698 | |||

| Benefit-based dependence | BD1 | 0.908 | 63.479 | 0.934 | 0.825 |

| BD2 | 0.894 | 38.112 | |||

| BD3 | 0.923 | 75.021 | |||

| Setup activity | SA1 | 0.864 | 29.179 | 0.882 | 0.713 |

| SA2 | 0.868 | 32.131 | |||

| SA3 | 0.800 | 23.689 | |||

| Learning | LC1 | 0.878 | 39.547 | 0.904 | 0.759 |

| LC2 | 0.891 | 46.058 | |||

| LC3 | 0.844 | 27.048 | |||

| Termination costs | TC1 | 0.852 | 34.346 | 0.884 | 0.717 |

| TC2 | 0.857 | 36.151 | |||

| TC3 | 0.832 | 28.244 | |||

| Cost-based dependence | CD1 | 0.773 | 19.950 | 0.817 | 0.600 |

| CD2 | 0.843 | 32.153 | |||

| CD3 | 0.702 | 13.118 | |||

| Continuance intention | CI1 | 0.843 | 19.495 | 0.898 | 0.747 |

| CI2 | 0.910 | 53.608 | |||

| CI3 | 0.838 | 24.016 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic support | 0.854 | |||||||||

| Technical support | 0.778 | 0.809 | ||||||||

| Social support | 0.690 | 0.691 | 0.834 | |||||||

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.668 | 0.712 | 0.713 | 0.909 | ||||||

| Benefit-based dependence | 0.750 | 0.685 | 0.717 | 0.742 | 0.909 | |||||

| Setup activity | 0.332 | 0.379 | 0.421 | 0.385 | 0.490 | 0.844 | ||||

| Learning | 0.458 | 0.476 | 0.484 | 0.433 | 0.548 | 0.798 | 0.871 | |||

| Termination costs | 0.255 | 0.306 | 0.325 | 0.263 | 0.379 | 0.580 | 0.523 | 0.847 | ||

| Cost-based dependence | 0.573 | 0.572 | 0.576 | 0.548 | 0.651 | 0.566 | 0.626 | 0.598 | 0.775 | |

| Continuance intention | 0.548 | 0.561 | 0.541 | 0.549 | 0.538 | 0.370 | 0.460 | 0.495 | 0.643 | 0.864 |

| VIF | 3.207 | 3.238 | 2.650 | 2.856 | 3.139 | 3.237 | 3.228 | 1.864 | 2.076 | — |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Fan, L. Understanding Incubated Startups’ Continuance Intention towards Entrepreneurial Incubation Platforms: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315802

Zhang Y, Liu X, Fan L. Understanding Incubated Startups’ Continuance Intention towards Entrepreneurial Incubation Platforms: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315802

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yanan, Xinmin Liu, and Liu Fan. 2022. "Understanding Incubated Startups’ Continuance Intention towards Entrepreneurial Incubation Platforms: Empirical Evidence from China" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315802

APA StyleZhang, Y., Liu, X., & Fan, L. (2022). Understanding Incubated Startups’ Continuance Intention towards Entrepreneurial Incubation Platforms: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability, 14(23), 15802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315802