Community Tourism Strategic Planning—Convergent Model Proposal as Applied to a Municipality in Mexico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Community Tourism as an Alternative in the Face of New Realities

3. The Importance of Applied Strategic Planning

- It allows the offering of adequate responses to the needs and demands of citizens, favoring greater efficiency and effectiveness of public intervention, from the political field.

- It allows for the planning of actions to be undertaken within the territorial scope and competence of local authorities.

- Through planning, the impact of the measures adopted on the population of the municipality can be calculated.

- It favors an adequate allocation of public resources to the needs and demands considered a priority by both citizens and rulers.

- It deepens the values of direct democracy by involving citizens in decision making; it allows for the inclusion of different and varied segments of the population with diverse interests and claims.

- It allows for reaching greater levels of consensus in the implementation of public programs and reduces the chances of failure that may occur.

- It allows “getting it right” with the needs and aspirations of citizens by incorporating them into the decision-making process.

4. Convergence between Strategic Planning and Community Tourism Replicable in Local Contexts

5. Implementing the Convergent Model to a Case Study

6. Contributions to Strategic Planning in Community Tourism

6.1. Research Results

- Matrix of potentialities, limitations and problems.

- Problem tree.

- Objective tree.

- Matrix of strengths, opportunities, weaknesses and threats.

- Matrix of local development objectives and strategies.

6.2. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Practical Lessons

9. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aas, C.; Ladkin, A.; Fletcher, J. Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maldonado-Erazo, C.P. Strengthening of Community Tourism Enterprises as a Means of Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Case Study of Community Tourism Development in Chimborazo. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino Villavicencio, B.; Gasca Zamora, J.; López Pardo, G. El turismo comunitario en la Sierra Norte de Oaxaca: Perspectiva desde las instituciones y la gobernanza en territorios indígenas. El Periplo Sustentable 2016, 30, 6–37. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Nair, V.; Ramachandran, S. Community Participation in Rural Tourism: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ballesteros, E.R. Claves del turismo de base local. Gaz. De Antropol. 2017, 33, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Geilfus, F. Ochenta Herramientas para el Desarrollo Participativo. Diagnóstico, Planificación, Monitoreo, Evaluación; Proyecto Regional IICA-Holanda: San José, Costa Rica, 2009; Available online: http://repiica.iica.int/docs/B0850e/B0850e.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Keogh, B. Public participation in community tourism planning. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Santiago, M.D.R.; Méndez-García, E.; Sánchez-Medina, P.S. A Mixed Methods Study on Community-Based Tourism as an Adaptive Response to Water Crisis in San Andrés Ixtlahuaca, Oaxaca, Mexico. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebele, L.S. Community-based tourism ventures, benefits and challenges: Khama Rhino Sanctuary Trust, Central District, Botswana. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D.G. Community participation in tourism planning. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Sharman, A. Collaboration in local tourism policymaking. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatmoko, S.; Kabil, M.; Purwoko, Y.; Dávid, L.D. Rethinking Sustainable Community-Based Tourism: A Villager’s Point of View and Case Study in Pampang Village, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, C.S.; Cardenas, D.; Viren, P.P.; Swanson, J.R. Using a community tourism development model to explore equestrian trail tourism potential in Virginia. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgaz Aguëra, F. El turismo comunitario como herramienta para el desarrollo sostenible de destinos subdesarrollados. Nómadas Rev. Crítica Cienc. Soc. Juríd. 2013, 38, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamilton, K.; Alexander, M. Organic communuty tourism: A concreated approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Chaves, A.; Solís-Rosales, S. Turismo y Patrimonio cultural inmaterial: Alternativa de complementariedad para el desarrollo de los territorios rurales. Rev. Espiga 2016, 15, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez, J.; Ferrer García, C. El Pasado en su Lugar Patrimonio Arqueológico, Desarrollo y Turismo. 2014. Available online: http://mupreva.org/pub/264/es (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Matos Silva, F.; Sousa, C.; Albuquerque, H. Albuquerque. Analytical Model for the Development Strategy of a Low-Density Territory: The Montesinho Natural Park. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos Doria, R. El turismo comunitario como iniciativa de desarrollo local. Caso localidades de Ciudad Bolívar y Usme zona rural de Bogotá. Hallazgos 2016, 13, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pintos, P.; Longo, J.; Delucchi, D.; Pereira, A. Planificación estratégica en tiempos de crisis: La necesidad de la permanente readecuación metodológica. In Memoria Académica; Universidad Nacional de la Plata: La Plata, Argentina, 2003; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, G.; Peralta, J.M.; Walter, P. Turismo rural y comunitario. Herramientas y aporte metodológico para acompañar al sector en la reapertura poscuarentena 2020 por covid-19. Rev. Argent. De Investig. En Neg. 2021, 7, 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019 Travel and Tourism at a Tipping Point; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TTCR_2019.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Organización Mundial del Turismo. El Turismo Retrocede a Niveles de 1990 con una Caída en Llegadas del más del 70%. UNWTO, 17 de diciembre de 2020. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/news/el-turismo-retrocede-a-niveles-de-1990-con-una-caida-en-llegadas-del-mas-del-70 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. El Comité de Emergencias Sobre la COVID-19 Presta Asesoramiento Sobre Variantes y Vacunas. Comunicados de prensa/El Comité de Emergencias sobre la COVID-19 presta asesoramiento sobre variantes y vacunas, 15 de enero de 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/15-01-2021-emergency-committee-on-covid-19-advises-on-variants-vaccines (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- World Economic Forum. Latin America and Caribbean Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Landscape Report: Assessing Regional Opportunities and Challenges in the Context of COVID-19. World Economic Forum, July 2020. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_LAC_Tourism_Compet_Report_2020.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- World Economic Forum. 24a Reunión de la Asamblea General de la OMT 2021. Reunión de la Asamblea General de la OMT. Sesión Temática. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/24-reunion-de-la-asamblea-general-de-la-omt/sesion-tematica (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- World Economic Forum. Travel & Tourism Development Index 2021 Rebuilding for a Sustainable and Resilient Future. World Economic Forum, May 2022. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Travel_Tourism_Development_2021.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Pérez Corona, J.; Planeación Territorial en la Región Sureste de Mexico en el Marco del Tren Maya. Alternativas de Desarrollo y Sustentabilidad, III. 2021. Available online: http://ru.iiec.unam.mx/5533/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Secretaría de Gobernación. Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2019–2024 en Diario Oficial de la Federación. Diario Oficial de la Federación, 12 de julio de 2019. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5565599&fecha=12/07/2019#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Andrade Romo, E. Turismo Cultural Comunitario; Consejo Nacional para las Culturas y Artes/National Council of Culture and Arts: Puebla, Mexico, 2012; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Román, M.P.P.; Sánchez, E.M.; Cortes, C.C. Descentralización, territorio y políticas sociales: Herramientas de combate a la pobreza en Mexico. Factores Críticos y Estratégicos en la Interacción Territorial Desafíos Actuales y Escenarios Futuros; Asociación Mexicana de Ciencias para el Desarrollo Regional: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020; Volume III, pp. 455–472. Available online: http://ru.iiec.unam.mx/5168/ (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Zielinski, S.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.; Milanés, C.B. Why Community-Based Tourism and Rural Tourism in Developing and Developed Nations are Treated Differently? A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, T.B.; Petrick, J.F. Augmenting the Role of Tourism Governance in Addressing Destination Justice, Ethics, and Equity for Sustainable Community-Based Tourism. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 2, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés Hernández, L.A. Planeación Estratégica con Enfoque Sistémico, 1st ed.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014; Available online: http://docencia.fca.unam.mx/~lvaldes/libro/planeacion_estrategica_2_Edicion.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Mintzberg, H.; Ahlstrand, B.; Lampel, J. Safari a la Estrategia; Ediciones Granica: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Téllez Tolosa, L.R. Pensamiento estratégico y desarrollo de competencias gerenciales: Una perspectiva desde las unidades de información. Rev. Códice 2005, 1, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lira, I.S.; Sandoval, C. Metodología para la Elaboración de Estrategias de Desarrollo Local; Comisión Económica para América Latinayel Carib: Santiago, Chile, 2012; Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/5518 (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Sáez, M.A.; Vargas, R.G.; Márquez, J.L. Participación ciudadana y planificación estratégica. Los planes especiales de inversión y actuación territorial (PEI) de Madrid. Contrib. A Las Cienc. Soc. 2007, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cebrián Abellán, F.; García González, J.A. Propuesta metodológica para la identificación, clasificación y puesta en valor de los recursos territoriales del turismo interior. La provincia de Albacete. Boletín De La Asoc. De Geogr. Españoles 2010, 361–383. [Google Scholar]

- Boronyak, L.; Asker, S.; Carrard, N.; Paddon, M. Effective Community Based Tourism: A Best Practice Manual for Peru; Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre: Sydney, Australia, 2010; Available online: https://www.apec.org/docs/default-source/Publications/2010/6/Effective-Community-Based-Tourism-A-best-practice-manual-for-Peru-June-2010/210_twg_EffectiveCommunityBased-Tourism_PeruVersion.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Zedeño Valmaseda, A.R.; Pérez Díaz, E.; Meneses Meneses, C.J. La gestión de la estrategia de desarrollo local. Caso municipio La sierpe, Cuba. Rev. Univ. Caribe 2021, 26, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukhliev, I.S.; Abdukhamidov, S.A. Strategic planning processes in regional tourism in the digital economy. Cent. Asian J. Innov. Tour. Manag. Financ. 2021, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, D. Recursos turísticos y atractivos turísticos: Conceptualización, clasificación y valoración. Cuad. Tur. 2015, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de Información Topográfica E14D58 Tlacolula de Matamoros. Mexico; 2014. Available online: https://datos.gob.mx/busca/dataset/mapas-topograficos-escala-1-50-000-serie-iii-oaxaca/resource/108d04d1-0853-4242-ac22-8aa13445e10c (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de Información Topográfica E14D59 San Pedro Quiatoni. Mexico. 2015. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/mapas/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Gobierno Municipal de Tlacolula de Matamoros. Plan de Desarrollo Municipal 2017–2018. 2016. Available online: http://www.ped2016-2022.oaxaca.gob.mx//BM_SIM_Services/PlanesMunicipales/2017_2019/551.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. Atlas de Infraestructura y Patrimonio Cultural de Mexico. Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. Available online: http://sic.gob.mx/atlas2010/fo/ATLAS-1a-parte.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Gobierno del estado de Oaxaca. Rutas Turísticas de Oaxaca. Rutas Turísticas. 2022. Available online: https://www.oaxaca.gob.mx/sectur/rutas-turisticas/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Estadisticas de Visitantes a Sitios Arqueológicos. Estadisticas de Visitantes. 2021. Available online: https://www.estadisticas.inah.gob.mx/ (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Instituto Politécnico Nacional. Estudio de Competitividad Turística del Destino de Oaxaca de JUÁREZ. Secretaría de Turismo; 2014. Available online: https://www.sectur.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/PDF-Oaxaca.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Behar Rivero, D.S. Metodología de la Investigación; Editorial Shalom: Lima, Peru, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Gayou Jurgenson, J.L. Cómo Hacer Investigación Cualitativa: Fundamentos y Metodología; Ediciones Culturales Paidós: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019; Available online: http://www.derechoshumanos.unlp.edu.ar/assets/files/documentos/como-hacer-investigacion-cualitativa.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Directorio Estadístico Nacional de Unidades Económicas 2015. 2015. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/mapa/denue/ (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- De Uña Álvarez, E.; Villarino Pérez, M. Configuraciones de identidad en territorios del turismo. Condiciones generales en Galicia. Cuad. Tur. 2011, 259–272. [Google Scholar]

- Münch Galindo, L. Planeación Estratégica. El Rumbo Hacia el Éxito; Trillas: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Altés, C.; Gómez Lorenzo, J.J.; Turismo y Desarrollo en Mexico. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, October 2008. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/document/Turismo-y-desarrollo-en-M%C3%A9xico.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Gobierno de Chile. Guía Metodológica para Proyectos y Productos de Turismo Cultural Sustentable; Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes/National Council of Culture and Arts: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2008; Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/guia-metodologica-turismo-cultural.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- Bertoni, R.; Castelnovo, C.; Cuello, A.; Fleitas, S.; Pera, S.; Rodríguez, J.; Rumeau, D. ¿Qué es el desarrollo? ¿Cómo se produce? ¿Qué se puede hacer para promoverlo? Departamento de Publicaciones, Unidad de Comunicación de la Universidad de la República (UCUR): Montevideo, Uruguay, 2011; Available online: https://www.colibri.udelar.edu.uy/jspui/bitstream/20.500.12008/21092/1/%c2%bfQue%cc%81-es-el-desarrollo%281%29.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

| Indicator | Ranking 2019 (1–140) |

|---|---|

| Enabling environment | 19 |

| Business environment | 98 |

| Safety and security | 126 |

| Health and hygiene | 70 |

| Human resources and labor market | 75 |

| Preparedness for information and communication technologies (ICT) | 81 |

| T & T (Travel and Tourism) Policy and Enabling Conditions | 50 |

| Prioritization of travel and tourism | 29 |

| International openness | 48 |

| Price competitiveness | 84 |

| Environmental sustainability | 108 |

| Infrastructure | 48 |

| Air transport infrastructure | 37 |

| Land and port infrastructure | 75 |

| Infrastructure of tourist services | 46 |

| Natural and cultural resources | 5 |

| Natural resources | 1 |

| Cultural resources and business trips | 10 |

| Author | Factors for the Development of CT |

|---|---|

| Maldonado et al., 2022 [22] | The management and defense of ancestral territories inhabited by the country’s peoples and nationalities. The generation of benefits from the protection and preservation of the cultural and natural heritage of the inherited territories. The valuation of culture as a mechanism for the strengthening of identities based on synchronous and asynchronous dimensions. Organizational strengthening for the vindication of collective rights. |

| Dangi & Petrick 2021 [20] | Engagement/participation Community assets Collaboration Cultural and heritage preservation Equity and local ownership Economic benefits Empowerment Leadership Job opportunities Environmental protection and management Infrastructure development |

| Ruiz, 2017 [4] | The consistency of the community as a framework for collective action and decision. The role of local leaders in tourism projects. The level of intensity of external intervention in the development of these initiatives. The local appropriation of tourism phenomena and products. The ways in which local society is inserted, through tourism, into the market. |

| Stage | Definition | Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Information collection activity to evaluate the potential development capacity of the locality under study. It proposes to analyze the information corresponding to the socioeconomic base and the development capacity of the community To carry out a rapid diagnosis, we will resort, first of all, to conducting interviews with key informants, direct observation and experience of the participants. | Matrix of potentialities, limitations and problems |

| Definition of vocations for local development | Vocations are understood as the aptitudes, abilities or special characteristics that the territory has for its development. An interesting approach to the subject of vocations is one which refers to the need to venture into the issue of local identity and according to what has been expressed above, should be the center of a territorial development strategy. | Vocations are defined from the matrix of potentialities and limitations |

| Definition of strategic and specific objectives | The identification of specific objectives will depend on the characteristics of the area, the existing connections between local economy and foreign economies, potential for economic growth and existing economic groups. | Problem Tree Goal Tree |

| Definition of the local development strategy | After defining the objectives, the next step will be to decide how to reach them. That is, the lines of action and intervention necessary to achieve the proposed goals. The measures must have an impact on the factors that cause the problems and/or prevent the birth of new activities. | SWOT Matrix Matrix of local development objectives and strategies |

| Id | Dimensions | Theoretical Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| SP1-CT3 | Organizational Philosophy–Authenticity of Tourism Activities 1 | The articulation of the organizational philosophy of a municipality or tourist locality is constructed, taking into consideration the essence and authenticity of tourist activities. These in turn are a reflection of the presence of pride and identity of the environment. The mission therefore defines a specific situation in which tourist activity is managed and concretized in the definition of objectives and strategies. On the other hand, the vision is constructed while considering the aspirations of the community to deploy its potentialities in the field of tourism and local development. “Considering different possible scenarios and identifying a shared vision for the future is a valuable exercise for communities to undertake and to ensure that everyone’s views on community tourism are actively heard and considered” [40]. Including these elements in the organizational philosophy and giving them formality in a document, will denote the authenticity of the locality compared to other tourist destinations, and therefore position it as an attractive option; this will also define a clear course to pursue during planning and management. |

| SP2-CT1 | Diagnosis–identification of tourist attractions 2 | The diagnosis represents the starting point within the planning process; it is necessary to know the environment of the tourist area and identify the existing tourist resources and attractions, as well as the conditions in which they are in order to improve and/or preserve their use. With the diagnosis, it is possible to define policies, programs, and plans for tourism development because the specific conditions of the locality are taken into account. By way of example, the diagnostic stage consists of “(a) prior collection of information, background and regulations; (b) seminar and workshop (SWOT and stakeholder map); (c) participatory tour and observation; (d) contribution of the members of the group from their local knowledge; and (e) sharing” [21]. |

| SP3-CT2 | Participation–community leadership. 3 | Community tourism is characterized by the involvement of the entire community (residents, a management team, community leaders, commercial entities, and the government among others) in the management of tourism activity, and it is the community itself that decides the type and level of participation according to their needs, expectations, capabilities and the balance with other obligations or activities that take place in the same territory. The organization of the community and its participation in tourism activities have the objective of improving the conditions of the local population and making the benefits of tourism activity fall on the community itself. For this reason, it is important that a strategic community leadership is forged to direct, manage and defend the values and objectives agreed and established. |

| SP2-CT4 | Diagnosis of the visitors hosted–cultural exchange with visitors 4 | It is important that the tourism offer is clearly defined by the community, considering the target population (tourists) to which it will be directed, in such a way that tourists have a local experience in line with their expectations. This task can be implemented from the diagnostic stage in which data sources collected during the tourist’s stay are used, such as general characteristics of the tourist, comments, and suggestions. This feedback helps to improve the tourist experience. There is also another important aspect related to social–cultural sustainability that has to do with the mutual exchange between tourists and the community. The community, on one hand, provides a unique local tourism experience in which the inhabitants share their customs, traditions and ways of life; the tourist, on the other hand, in addition to financial remuneration, lives the experience harmoniously, taking care of and respecting the cultural, social and environmental contexts. In this way, mutually beneficial relationships are forged. |

| Cts | Strategies for Community tourism 5 | The strategic planning of community tourism is implemented by the generation of strategies that will be applied in the long term for the development of tourism activity, and that encompass the aspects described above. The strategies are designed in the planning stage and are permanently implemented during the development of tourist activity. However, they can be modified during the review and/or evaluation stage, depending on the changing conditions and consideration of the decisions made by the community as a whole. |

| Ld | Local Development 6 | From the strategic planning and the diagnosis of community tourism emerge the strategies for the development of tourism activity, which lead to local development, understanding development as “that which has a spatial character, occurs in a specific place, in a certain territory, where a particular population is in interaction with the environment and produces its own history, customs, and culture. On the other hand, the forms of local governments, peculiar and authentic in themselves, are the platform on which development is built, regardless of the source of resources” (p. 64, [41]). |

| Strategic Planning | Categories |

|---|---|

| Philosophy of the organization | OP1. Mission |

| OP2. Vision | |

| Diagnosis | D1. Knowledge of tourist attractions |

| D2. Sources of information | |

| D3. Media | |

| D4. Organizations and institutions | |

| D5. Visitors received | |

| D6. Opportunities | |

| D7. Challenges | |

| D8. Difficulties | |

| Community Engagement | CP1. Community inclusion |

| CP2. Public spaces | |

| CP3. Participation in the planning process | |

| CP4. Participation in implementation | |

| Community tourism | Categories |

| Identification of tourist attractions | TAI1. Endogenous resources |

| TAI 2. Accessibility | |

| TAI 3. Signage | |

| TAI 4. Quality of the environment | |

| TAI 5. Main problems | |

| Community Leadership | CL1. Projects originating from the community |

| Authenticity and value | AV1. Pride and identity |

| AV2. Natural and cultural environment | |

| AV3. Enhancement | |

| Cultural exchange | CI1. Relationship with the visitor |

| Subsection | Categories |

|---|---|

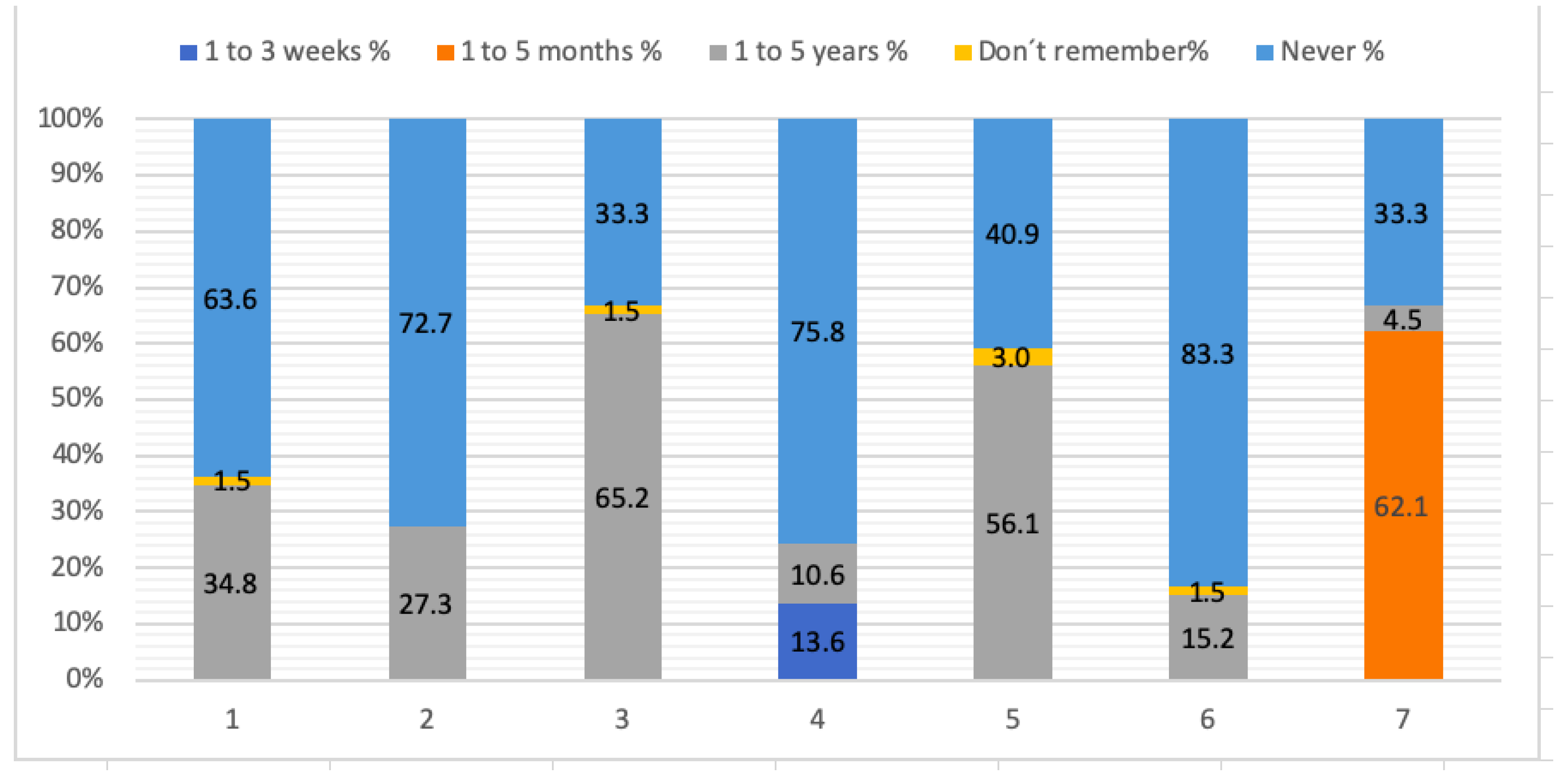

| Tourist attractions and community | TA & C1. Knowledge of the existence of tourist attractions |

| TA & C2. Last visit to tourist sites | |

| TA & C3. Participation in the cleaning, visual improvement, restoration or conservation of the attractions | |

| TA & C4. Participation in the planning and organization of tourism activities. | |

| Community tourism | CT1. Attendance at community assemblies |

| CT2. Condition of community spaces | |

| CT3. Inclusion of the community in activities that favor tourism development | |

| CT4. Motivation of the community in activities that favor touristic development | |

| CT5. Participation in the evaluation of tourism projects in the municipality | |

| CT6. Willingness to make complaints or suggestions known to the corresponding authorities | |

| CT7. Participation in tourist fairs for commercial interestParticipation in tourist fairs due to interest in the culture of the municipality of Tlacolula de Matamoros | |

| CT8. Relationship with the tourist or visitor | |

| CT9. Pride from being a native of Tlacolula | |

| CT10. Practice of customs | |

| CT11. Practice of traditions | |

| CT12. Identification with the elements of cultural identity | |

| CT13. Identification with touristic attributes | |

| General Data | GD1. Age of respondents |

| GD2. Sex | |

| GD3. Place of birth | |

| GD4. Speaking of indigenous language | |

| GD5. Degree | |

| GD6. Activity carried out last week | |

| GD7. Workstation | |

| GD8. Tourists at the workplace | |

| GD9. Suggestions for the improvement of tourism |

| Stage | Parent Elements | Beginning | Development | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of key and community actors | Key actors | Intentional selection of interviewees 1 | Inquiry into possible actors involved in tourism development of the municipality. | List of key actors with contact details (Table 8) |

| Information Collection | Semi-structured interview guide | Development of instrument with 24 categories of analysis | Six interviews were applied in the period 2 March to 7 April 2018. | Six interview guides answered |

| Information Processing | Print interviews answered | Review of interviews, coding | Capture and encoding of the information collected in Excel database | Identification of problems expressed by key stakeholders, through content analysis 2 |

| Stage | Parent Elements | Beginning | Development | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maps and information from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography [44] Mexico Digital Map Software 6.3.0 | Map processing of the urban center of Tlacolula de Matamoros. The layers of basic geo-statistical areas (AGEB key) 1 were used, with information on blocks and population in shp format | The data corresponding to the number of blocks and occupied dwellings were subtracted and corroborated the information through the National Statistical Directory of Economic Units (DENUE) 2 | The data was transcribed and encoded into an excel document. A total of 3689 homes and 355 blocks were identified. |

| Excel software book with the total of homes and blocks | Application of the sampling formula to blocks. A confidence level of 90% was used with 10% error | The application of the formula yielded 56.81 (57) out of 355 blocks. Subsequently, a simple random sampling was performed with Excel | List of 57 selected blocks with the respective keys that INEGI grants to each block. | |

| List of 57 blocks Map of the urban center of Tlacolula de Matamoros | Selection of the 57 blocks on the digital map. | Verification of the existence of dwellings in the blocks selected according to the DENUE database. | Three blocks of the 57 that did not have homes were identified, which were randomly replaced by others that did have homes. | |

| Questionnaire with closed questions (Likert scale 1–5). Maps printed with the selected blocks. | Development of an instrument with 27 categories of analysis | The questionnaires were applied to available residents of homes located north of the lower right quadrant of each selected block over 15 years of age. | 57 questionnaires answered |

| Printed questionnaires answered | Survey review and coding | Capture of information collected in the Software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) | The analysis allowed to generate descriptive statistics and the correlation of graphically captured variables |

| Tourist Attraction | Key Player |

|---|---|

| Tlacolula de Matamoros as a tourist municipality | Director of Tourism |

| Fairs that promote the cultural elements of the municipality (roast meat expo, red clay craft fair, patronal fair expo, cultural Sundays, bread and chocolate fair, agro-biodiversity fair and the ice-cream and mezcal fair which continues to be promoted) | Tourism Committee |

| Martín González market and Tianguis | Market Manager |

| Archaeological sites: Yagul and Lambityeco. | Anthropologist |

| Chapel of the Lord of Tlacolula | Coordinator of Church Pastoral Care |

| Jaguar Xoo Conservation Center | Director |

| Category | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Strategic Planning | |

| OP1. Mission | Currently the municipality does not have a mission as a tourist municipality; therefore, the activities that have been carried out for tourism development have been short term |

| OP2. Vision | The vision of the municipality of Tlacolula de Matamoros in the future (20 years) is of a municipality with a strong tourist influx and with tourist infrastructure that supports the demands of tourists. There was no mention of the interest in encouraging greater inclusion of the community in tourism projects. A vision of conventional tourism can be perceived, in which the creation of hotels and the improvement of the tourist infrastructure are priority conditions for the development of the activity. |

| Category | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Strategic planning | |

| D1. Knowledge of tourist attractions | The municipality is considered to have a natural, cultural, and historical wealth in its territorial resources. However, not enough work has been done on tourism promotion both inside and outside the municipality to take advantage of its tourist potential. |

| Community tourism | |

| TAI1. Endogenous resources | The endogenous resources exploitable for tourist activity are mainly the artisanal mezcal and red clay of the town of San Marcos Tlapazola |

| TAI2. Accessibility | There are not enough parking lots to meet the demand of visitors especially on “Market Sundays”. Furthermore, the access road to the archaeological zone of Yagul is in very poor condition |

| TAI3. Signage | The signage of the tourist attractions is insufficient, and the existing ones are not very visible |

| TAI4. Quality of the environment | The environment of the “Martín González” market has lost its air of traditionality as there is a disorganization between the stalls and the products offered |

| CL1. Projects originating from the community | The project taken up from a proposal by the community was the roasted meat fair |

| AV1. Pride and identity | Gastronomy was presented as the element of identity pride |

| AV2. Natural and cultural environment | The community is very indifferent to the environment, especially the archaeological sites. |

| AV3. Enhancement | The cultural elements that could be valued are: the traditional clothing designs of “Market Sunday” vendors, the cosmogony of the villages of the Tlacolula Valley, the historical value of the archaeological zones, especially the prehistoric caves of Yagul and Mitla |

| Id | Dimensions | Practical Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| SP1-CT3 | Philosophy of organization–authenticity of tourism activities | There is a lack of an organizational philosophy aimed at the development of community tourism and on the other hand there is weak recognition of the elements of identity, a factor that has an impact on enhancing the authenticity of the tourist municipality. The elements of identity recognized and valued by the community must be integrated into the organizational philosophy of the tourist municipality, in order to incorporate them into the objectives, activities and strategies that are contemplated in a tourism development plan. |

| SP2-CT1 | Diagnosis–identification of tourist attractions 2 | According to the classification of Altés Machín (1995, p. 33) cited in Navarro (p. 344, [43]), the municipality has 16 out of the 19 tourism resources among which are the fairs and touristic sites; it should be noted that the community has had greater participation in the planning and management of the fairs. However, some sites present unfavorable conditions for the development of touristic activity. The diagnosis generated during the research shows the need to analyze in depth the conditions of each site, considering other factors such as the inclusion of the community, since in the same way ignorance and disinterest in both fairs and tourist sites are perceived. |

| SP3-CT2 | Participation–community leadership. | The participation of the community in tourism management is not perceived. The perception of the community is that it is not included in the decision-making concerning tourism development. Likewise, its opinion is excluded when a new touristic activity is implemented. On the other hand, no evidence of community leadership was found, which includes community autonomy in tourism planning and management. This situation is an effect of the absence of grounded participation mechanisms. For this specific case in the municipality, it is necessary that the local government in coordination with other groups of tourist interest are the mediators in implementing participatory mechanisms that, in the long term, give rise to the development of community leadership. |

| SP2-CT4 | Diagnosis of the visitors received–cultural exchange with the visitor | The municipality has not clearly defined the type of tourism that it intends to develop, therefore the type of target tourists is not defined either. On the other hand, at the beginning of 2017 it began with the collection of information from tourists hosted only on Sundays, which represents a first approach to finding out the interests of tourists when visiting the Municipality. As for socio-cultural exchange, although the inhabitants share their customs, traditions, and ways of life during the activities carried out in the fairs, in addition to the economic remuneration, factors that promote a harmonious coexistence between tourists and the socio-cultural environment of the Municipality yet to be identified. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zárate-Altamirano, S.; Rebolledo-López, D.C.; Parra-López, E. Community Tourism Strategic Planning—Convergent Model Proposal as Applied to a Municipality in Mexico. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315945

Zárate-Altamirano S, Rebolledo-López DC, Parra-López E. Community Tourism Strategic Planning—Convergent Model Proposal as Applied to a Municipality in Mexico. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315945

Chicago/Turabian StyleZárate-Altamirano, Stefanie, Deisy Coromoto Rebolledo-López, and Eduardo Parra-López. 2022. "Community Tourism Strategic Planning—Convergent Model Proposal as Applied to a Municipality in Mexico" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315945

APA StyleZárate-Altamirano, S., Rebolledo-López, D. C., & Parra-López, E. (2022). Community Tourism Strategic Planning—Convergent Model Proposal as Applied to a Municipality in Mexico. Sustainability, 14(23), 15945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315945